Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) are valuable therapeutic targets. To exploit them fully requires rapid assays for the evaluation of potentially therapeutic ligands and improved understanding of the interaction of such ligands with their receptor binding sites.

Experimental Approach:

A variety of neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) were tested for their ability to inhibit the binding of [125I]α-bungarotoxin to TE671 cells expressing human muscle AChRs. Association and dissociation rate constants for vecuronium inhibition of functional agonist responses were then estimated by electrophysiological studies on mouse muscle AChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes containing either wild type or mutant α1 subunits.

Key results:

The TE671 inhibition binding assay allowed for the rapid detection of competitive nicotinic AChR ligands and the relative IC50 results obtained for NMBAs agreed well with clinical data. Electrophysiological studies revealed that acetylcholine EC50 values of muscle AChRs were not substantially altered by non-conservative mutagenesis of phenylalanine at α1:189 and proline at α1:194 to serine. However the α1:Phe189Ser mutation did result in a 3-4 fold increase in the rate of dissociation of vecuronium from mouse muscle AChRs.

Conclusions and implications:

The TE671 binding assay is a useful tool for the evaluation of potential therapeutic agents. The α1:Phe189Ser substitution, but not α1:Pro194Ser, significantly increases the rate of dissociation of vecuronium from mouse muscle AChRs. In contrast, these non-conservative mutations had little effect on EC50 values. This suggests that the AChR agonist binding site has a robust functional architecture, possibly as a result of evolutionary ‘reinforcement'.

Keywords: nicotinic, vecuronium, receptor, KD, evolution, proline, phenylalanine, serine, TE671, binding

Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) are involved in mediating fast excitatory neurotransmission at the neuromuscular junction and at synapses in the central and peripheral nervous systems and are important therapeutic targets (e.g., Gotti et al., 2006; Jeevandra Martyn et al., 2006). The gene family of AChR subunits is a member of the Cys-loop superfamily of ligand-gated ion channel subunits, which also includes subunits of glycine, GABAA and 5-HT3 receptors. Muscle AChRs are comprised of five subunits, two of which are of the α1 type along with one each of β1, δ and either γ (embryonic form) or ɛ (adult form).

Muscle type AChRs on the postsynaptic terminal of neuromuscular junctions are a pharmacological target for neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs). Rapidly acting NMBAs are clinically indispensible in conditions such as emergency tracheal intubation. A short duration of action also adds to the level of control available to clinicians when they are undertaking limited procedures or need to monitor the maintenance of nerve function (Bartowski, 1999). Development of methods of screening for new NMBAs and improving the understanding of the molecular determinants of NMBA binding may facilitate the development of new drugs targeted at both muscle and neuronal AChRs.

We therefore developed a radioligand-binding assay that would enable the determination of the binding IC50s of a range of NMBAs. To do this we made use of the human cell line TE671 as a source of endogenous embryonic muscle AChRs (α1β1γδ; Schoepfer et al., 1988; Luther et al., 1989; Stratton et al., 1989), and [125I]α-Bungarotoxin (α-Bgt) as our radioligand.

We also wished to examine molecular determinants within receptor subunits that affect the action of NMBAs. Some previous studies have approached this question by exchanging whole subunits within mouse muscle type receptors. Using single concentrations of d-tubocurarine (d-TC, 10 nM), pancuronium (10 nM) and vecuronium (1 nM), Garland et al. (1998) found that whereas vecuronium was more potent than d-TC or pancuronium, it could not distinguish between the expressed foetal (αβɛδ) and adult (αβγδ) receptor subtypes. Conversely, Yost and Winegar (1997) reported that pancuronium was a more potent inhibitor of mouse muscle foetal receptors (IC50=1.7 nM) than the adult subtype (IC50=46 nM). Further studies are therefore necessary to clarify the actions of NMBAs on muscle type AChRs.

In contrast to these studies on NMBAs, much more is known about the molecular determinants of agonist binding (Blount and Merlie, 1989; Pedersen and Cohen, 1990). The amino acids that directly contribute to the agonist-binding sites are found in interfacing regions of αγ and αδ subunits, within multiloop structures of their respective N-terminals, (reviewed in Arias, 2000). As the NMBA vecuronium is a competitive antagonist of muscle AChRs, one might expect that amino acids, which influence vecuronium binding, may lie within the same regions. One of these regions, loop C in the mouse α1 subunit, contains phenylalanine and proline at positions 189 and 194, respectively.

These residues are of special interest as there are numerous clinical examples in which point mutations of Phe or Pro for Ser cause severe human disease. These include the hereditary spongiform encephalopathy Gerstmann–Straussler–Scheinker disease (prion protein Phe198Ser; Vanik and Surewicz, 2002); Romano–Ward syndrome, (KCNQ1 channel Pro343Ser, Zehelein et al., 2004); and diabetes (nuclear factor-1-α Pro224Ser, Fehmann et al., 2004). The reverse mutations can also be very harmful, as shown under conditions such as congenital myotonia (skeletal muscle chloride channel gene, Ser471Phe; Jou et al., 2004); familial dementia (neuroserpin Ser49Pro; Davis et al., 1999) and human colorectal cancer (serine/threonine protein phosphatase, Ser365Pro, Tagaki et al., 2000). One might therefore expect that the presence of Phe at α1:189 and Pro at α1:194 would be indispensable for the maintenance of functional architecture in muscle nicotinic AChRs and that a point mutation which changes them to serine would have major functional consequences. To investigate such questions, we additionally carried out site-directed mutagenesis on mouse muscle AChR subunits, expressed them in Xenopus oocytes, and monitored their responses electrophysiologically.

To determine how well the agonist sensitivity of muscle type AChRs is maintained when α1:Phe189 and α1:Pro194 are mutated to serine, the EC50 values of the acetylcholine (ACh) responses were estimated for wild-type (WT) and mutant receptors. The effects on inhibition were examined by electrophysiological estimation of the association and dissociation rate constants for vecuronium inhibition of muscle type AChRs.

In the present study, we found that the TE671-binding assay was a useful tool for the initial evaluation of NMBAs. More detailed analysis of the interaction of vecuronium with AChRs revealed that the α1:Phe189Ser substitution appears to affect significantly the rate of dissociation of vecuronium from mouse muscle AChRs. However, neither the presence of Phe at α1:189 nor Pro at α1:194 are essential for agonist activation.

Methods

Routine culture of TE671 cells

TE671 cells were obtained from the European Collection of Animal Cell Cultures (ECACC) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 4.5 g l−1 glucose, 10% foetal bovine serum, 1% sodium pyruvate and 1% glutamine. Cultures were split 1:4 twice weekly and were not used beyond passage 20.

TE671 whole cell binding assay-saturation experiments

Stock concentration and dilutions of [125I]α-Bgt were prepared in distilled water (pH 7.0) and test compounds were prepared in Organon buffer (supplied by the Pharmaceutical R&D Labs, Organon Oss, The Netherlands). This buffer (pH 4.0) was prepared by adding 8.3 mg citric acid (anhydrous weight), 6.5 mg dibasic sodium phosphate (anhydrous weight) and 24.5 mg D-mannitol to 1 ml of distilled water. TE 671 cells were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well. Twenty-four hours later the growth medium was removed by aspiration and the cells washed ( × 2) with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Wells were then loaded with excess (375 μl) N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulphonic acid (HEPES)–Krebs buffer (NaCl 118 mM, NaHCO3 30 mM, KCl 5 mM, KH2PO4 1 mM, MgSO4 1 mM, Glucose 11 mM, HEPES 20 mM, CaCl2 2.5 mM), pH 7.4.

For each concentration of [125I]α-Bgt, triplicate wells were loaded with 25 μl of Organon buffer to establish the total binding (BT) and a further three wells loaded with 25 μl of 0.1 mM tubocurarine to evaluate non-specific binding (NSB). Plates were incubated for 30 min at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% CO2/5% O2. After this, 100 μl of the appropriate concentration of [125I]α-Bgt (range 0.1–10.0 nM) was added to each well and the plates returned to the incubator for 2 h. Preliminary experiments suggested that equilibrium was achieved after this time.

The reaction was terminated by removing the incubation mixture and washing the cells ( × 3) with 0.5 ml of cold PBS. Cells were then solubilized and the samples were pooled and counted in a Minaxa auto gamma counter. The mean (n=3) counts per minute (cpm) for each sample were then used to find the specific binding (SB) from SB = cpm BT –cpm NSB. Total (BT), NSB and SB were calculated from the saturation experiments and plotted against the concentration of [125I]α-Bgt in Figure 1. The non-specific binding is fitted to E*X, where E is an arbitrary constant and X is the concentration of [125I]α-Bgt (nM). The specific binding is fitted to where Bmax is the maximum number of binding sites, KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant of the ligand (nM) and BT was the sum of specific and non-specific binding.

Figure 1.

Saturation plots of [125I]α-Bungarotoxin binding in whole TE671 cells. The range of toxin concentrations was 0.1–10 nM.

Inhibition of [125I]α-Bgt binding to TE671 cells

For the IC50 estimates, triplicate wells in each plate were loaded as before to determine BT and NSB. The remaining cells were loaded with 25 μl of one of six concentrations (0.01–100 μM) of test drug. Plates were incubated as described above and then 100 μl of [125I]α-Bgt was added to all wells and the plates incubated for a further 2 h and treated as explained previously. IC50 values for the inhibition of [125I]α-Bgt binding were then calculated by fitting the data to the Hill equation (see below).

Generation of mutants

Two mutant α1 subunit cDNAs were constructed using QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). The standard protocol supplied by the manufacturer was followed to produce mutations containing α1:Phe189Ser and α1:Phe189Ser +Pro194Ser. A third mutation, the α1:Pro194Ser mutant, was discovered during confirmatory sequencing of a recently purified plasmid preparation. The single base (CCC to TCC) mutation correspondingly coding for proline and serine may have arisen as a result of a DNA repair process within the host bacterium. The nucleotide sequence of all the constructs was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Functional expression of receptors in Xenopus laevis oocytes

Defolliculated oocytes were prepared for injection as described previously (Boulter et al., 1987). Diguanosine-triphosphate capped RNA was translated in vitro from the corresponding DNA templates using mMessage mMachine SP6 Transcription Kit (Ambion Europe Ltd. Huntingdon, UK). WT or mutant α1 subunit RNAs were mixed with β1, γ and δ subunits in a ratio of approximately 2:1:1:1. Up to 15 ng of RNA was injected into oocyte cytoplasm using Drummond Automatic Nanoinjector (Drummond Scientific Co., Broomall, PA, USA). The oocytes were then incubated in Barth's medium (88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 0.30 mM CaNO3·4H2O, 0.41 mM CaCl2·6H2O, 0.82 mM MgSO4·7H2O, sodium penicillin and streptomycin sulphate 10 μg ml−1 each) for 1–7 days at 16–18°C before commencing electrophysiological experiments.

Electrophysiological recording

Two-electrode voltage clamp recordings (VH=−60 mV; Axon Geneclamp 500, Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) were obtained for ACh-induced current responses 1–7 days after RNA injection. Current (RI=1.0–1.5 MΩ) and voltage (RV=1.5–3.0 MΩ) pipettes were filled with 3 M KCl. All external recording solutions, both control and those to which drugs have been added, contained 115 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 2.5 mM KCl, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). Atropine (1 μM) was included to block endogenous muscarinic currents within the oocytes. A gravity-driven manual switching system allowed either drug or control solution to be rapidly perfused (20–25 ml min−1) through an effective bath of volume 0.3 ml. Using this system, which minimizes dead–space, agonist responses plateau within about 2 s (and reaches approximately 90% of the peak within 1 s; see Connolly et al., 1992). This suggests that for small ligands, superfusion of the entire surface of the oocyte is essentially complete within this time period.

ACh concentration–response curves

In each cell, 2–3 reproducible control responses (5 min- time interval between successive agonist applications) were first obtained using a control concentration of ACh (1 μM) to which all subsequent data were normalized. To minimize the problem of desensitization, the last control response was followed by only a single application of one high concentration of agonist. About 4–25 oocytes were used at each concentration. The mean, normalized responses (±s.e.m.) were then plotted against the log of the corresponding ACh concentration and the data fitted to the Hill equation where I is the observed current response, Imax the maximum current response, X the agonist concentration, EC50 is the concentration of agonist which elicits a half-maximum response and nH is the Hill coefficient of agonist binding.

Drug application and determination of kinetics of vecuronium binding to AChRs

Two to three reproducible control responses at 3-min intervals were obtained using a control concentration of ACh (100 nM). About 1 min after the last control application of agonist, a particular concentration of vecuronium (3–100 nM) was applied. After 2 min (i.e., 3 min after the last control agonist response), oocytes were rechallenged with a mixture of 100 nM ACh in recording solution containing the same vecuronium concentration. It was assumed that at t=0, the agonist response would remain the same as the average of the initial control responses. During the course of the experiment, extreme care was taken to avoid any variations in the flow rate of all test solutions.

After the combined application of agonist plus vecuronium, the test solution was washed out in a perfusate containing vecuronium. Vecuronium was therefore continuously present in both the wash and test solutions. The ACh and vecuronium coapplications were repeated as vecuronium gradually bound to a larger and larger fraction of the receptors. The rate of increase of receptor occupancy by vecuronium was very high and therefore equilibrium was achieved very quickly and to aid fitting, the 100% (t=0) response was included in the data analysis. The continuous perfusion of antagonist and long time course used in this protocol should ensure if there is any irregularity in the first few seconds of vecuronium equilibration, it will only have a minimal effect on the response size at the first time point. Subsequent time points should not be affected at all. The diminishing agonist-induced responses were expressed as the percentage of the initial control response and were plotted against time and the data were fitted as a single exponential decay: where Y is the % current at time t following the application of the vecuronium, (100−plateau) is the difference between the initial control response (considered as 100%) and the estimated residual response after the block has come to a final equilibrium, and kon is the rate constant for the progress of inhibition and is equivalent to (1/τon), where τon is the time constant for the development of the current inhibition. Estimated kon values at a specific vecuronium concentration from different oocytes were averaged and a mean (±s.e.m.) ‘on-rate' was derived. These mean ‘on-rate' values were then plotted on a linear axis against respective concentrations of vecuronium. Data were fitted by the least-squares method to a straight line using the following equation: where k+1 is the microscopic association rate constant and the k−1 is the corresponding microscopic dissociation rate constant of vecuronium binding to the WT and the mutant AChRs. The k+1 value was obtained from the slope of the graph, whereas k−1 could be taken as the intercept of the fitted straight line on the y-axis. The equilibrium dissociation rate constant, KD, for the binding of the vecuronium to the WT and the mutant receptor was then calculated as The estimated KD values thus obtained provide a useful way of comparing the binding properties of different mutants. However, they only provide a single numerical value for each mutant and so cannot be statistically compared.

Recovery from vecuronium inhibition

In contrast, recovery rates, obtained from individual oocytes, can be compared. In normal oocyte Ringer solution (at 3-min time intervals between applications), 2–3 reproducible control responses to applied ACh (100 nM) were obtained. Control responses were accepted as being reproducible only if they were within 5% range of the average of other responses. About 1 min after the last control response, normal oocyte Ringer was replaced by Ringer containing vecuronium (200 nM) and oocytes were perfused for 6 min. Following this treatment agonist responses were almost completely inhibited. The perfusate was again switched back to normal Ringer (trec=0 min). Thereafter recovery responses to control ACh were recorded. It is expected that vecuronium near the oocyte surface will be cleared from the bath on a similar timescale to ACh after switching to control Ringer. Thus, any residual concentrations of free vecuronium should be very minor at the first recovery time point and should not significantly affect the overall time course of recovery from blockade.

To estimate the rate of recovery (krec), the recovery responses were expressed as a % of the initial control (100%) and were plotted as a function of time. The data were then fitted with a single exponential component using the following equation: Here, Y is the response at time t after removal of vecuronium expressed as a % of initial control response, C is the residual response after vecuronium blockade, krec the rate constant of recovery from vecuronium block at the receptor, and t the time of observation. krec is also an estimate of k−1, the microscopic dissociation rate of vecuronium binding. The krec values were compared between WT and all the mutant receptors. Using the actual observed residual responses as ‘C' in an individual oocyte (mostly <5% of the initial control response) improved the fitting to individual cell data.

Statistics and software

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test were used to determine the statistical significance of differences in the krec values of the expressed receptors (significance level 0.05). The F-test was used to compare single-versus two-component curve fitting. Means are given as ±s.e.m. and n-values refer to the number of oocytes in which the experiments were performed. GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used for plotting of graphs, curve fitting, and statistical analysis.

Materials

All reagents were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Company (Poole, UK) or Organon Laboratories (Newhouse, Scotland, UK) unless specified. Vecuronium for electrophysiological experiments was generously provided by Dr Chris Prior (University of Strathclyde).

Results

Saturation experiments

The mean values for total, specific and non-specific binding of 1–10 nM [125I]α-Bgt to TE671 cells obtained from three experiments are shown in Figure 1. Fitting of individual data sets to a one-site binding model allowed a mean pKd value of 9.15±0.06 (KD=0.73 nM) to be calculated. On the basis of this result, it was decided to use a concentration of 0.1 nM [125I]α-Bgt in the inhibition experiments described below. Specific binding as a percentage of BT varied between 77 and 90% over the range of toxin concentrations used.

Inhibition of [125I]α-Bgt binding by various steroidal and non-steroidal NMBAs in TE671 cells provides a fast assay for predicting the relaxant activity of novel compounds

Twelve clinically useful neuromuscular blockers and two peptides, were tested (n=3–12 experiments). Data ware analysed as described in the methods and the estimated IC50 values are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

IC50 values for inhibition of [125I]α-bungarotoxin binding to whole TE671 cells by neuromuscular blocking agents, compared to effective doses in man

| Compound | n | pIC50 | IC50 (nM) | Approximate 90% neuromuscular blocking dose in man (mg kg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Bungarotoxin | 3 | 10.0±0.50 | 0.1 | |

| d-Tubocurarine | 7 | 7.63±0.19 | 23 | 0.51a |

| Mivacurium | 4 | 7.50±0.14 | 30 | 0.07a |

| α-Conotoxin GI | 3 | 7.44±0.36 | 36 | |

| Vecuronium | 6 | 7.39±0.18 | 40 | 0.04b |

| Decamethonium | 3 | 7.18±0.37 | 66 | |

| Pancuronium | 12 | 7.11±0.09 | 78 | 0.07b |

| Rapacuronium (Org 9847) | 4 | 6.91±0.29 | 123 | 1.15c |

| Pipercuronium | 3 | 6.72±0.12 | 191 | |

| Rocuronium | 6 | 6.64±0.08 | 229 | 0.25d |

| Suxamethonium | 7 | 6.32±0.07 | 479 | 0.40e |

| Atracurium | 3 | 5.94±0.03 | 1150 | 0.20b |

| Gallamine | 3 | 5.90±0.07 | 1260 | 2.80f |

| Diadonium | 5 | 5.53±0.09 | 2950 | 5.00g |

Data are expressed as pIC50±s.e.m. from n experiments, and the corresponding IC50 value (μM).

References:

Of the five aminosteroids tested, pancuronium and vecuronium were more active as inhibitors of [125I]α-Bgt binding than rocuronium, pipecuronium or rapacuronium. The seven non-steroidal neuromuscular blocking drugs showed a wide range of activity with IC50 values from 20 nM for d-TC to 2.95 μM for diadonium. Within this range the descending order of potency of the remaining compounds was as follows: mivacuronium > decamethonium > suxamethonium > atracuronium > gallamine. As expected from the saturation binding study, α-Bgt had a very low IC50 and thus was over 300 times more active than the smaller peptide, α-conotoxin GI.

WT and mutant AChRs generally exhibit similar EC50 values for ACh activation, but show a slight decrease in Hill slope values for α1:Phe189Ser and α1:Phe189Ser + Pro194Ser receptors.

The ACh concentration–response relationship was first obtained for receptors containing WT α1 subunits. The percentage mean (±s.e.m.) current response to 1 μM ACh obtained for oocytes injected with approximately 15 ng of RNA was 568±56 nA (n=8), whereas for 2–3 ng RNA injected oocytes it was 11±1.1 nA (n=29). As described in the methods, responses to a wide range of ACh concentrations (10 nM–3 mM) within a cell were normalized to the mean of the current responses to a standard concentration of 1 μM ACh within that same cell. As shown in Figure 2, the estimated EC50 of ACh activation of WT receptors was 23.6 μM with a Hill coefficient of 1.2 (Table 2).

Figure 2.

ACh concentration–response curves. ACh concentration–response curve for receptors containing WT (n=4–29 oocytes at each concentration), α1:Pro194Ser (n=4–16 at oocytes each concentration), α1:Phe189Ser (n=4–28 oocytes at each concentration) and α1:Phe189Ser +Pro194Ser (n=4–25 oocytes at each concentration) subunits were obtained as described in the Methods. The estimated EC50 values for the corresponding receptor types were 23.6 μM (nH=1.2), 29.0 μM (nH=1.3), 42.1 μM (nH=1.00) and 77.7 μM (nH=0.91), respectively. All data were normalized to a standard response of 1 μM ACh in each experiment. Differences in the peak responses at 1 mM ACh were not significant (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-test), although it would appear that mutants containing Phe189Ser have slightly different agonist activation properties.

Table 2.

Summary of pharmacological and kinetic properties of ACh and vecuronium binding to WT and mutant AChRs

| Ligand | Pharmacological Parameter | Receptor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | α1:Pro194Ser | α1:Phe189Ser | α1:Phe189Ser+Pro194Ser | ||

| ACh | ACh EC50 (μM) | 23.6 | 29.0 | 42.1 | 77.7 |

| Hill coefficient | 1.20 | 1.30 | 1.00 | 0.90 | |

| Vecuronium | k+1 ( × 106 M−1 min−1) | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| k-1 ( × 10−2 min−1) | 8.2 | 7.8 | 18.0 | 13.0 | |

| KD (nM) Jenkinson method | 75.0 | 65.0 | 128.5 | 81.3 | |

| krec ( × 10−2 min−1) | 2.9±0.6 (n=4) | 3.8±0.1 (n=3) | 11.0±2.0a (n=8) | 16.5±2.1b,c (n=4) | |

| KD (nM) Recovery method | 26.4 | 31.0 | 78.6 | 103.1 | |

Abbreviations: ACh, acetylcholine; AChRs, acetylcholine receptors; WT, wild type.

P<0.05, comparison of krec estimated at 200 nM vecuronium preincubated for 6 min for α1:Phe189Ser against WT.

P<0.01, comparison of krec value after 6 min preincubation of 200 nM vecuronium for α1:Phe189Ser +Pro194Ser against WT.

P<0.01, comparison of krec value after 6-min preincubation of 200 nM vecuronium for α1:Phe189Ser +Pro194Ser against α1:Pro194Ser.

ACh concentration–responses curves were then obtained for all the mutant receptors. The % mean (±s.e.m.) current responses to 1 μM ACh of receptors containing α1:Pro194Ser for oocytes injected with 15 and 2–3 ng RNA were 616±94 and 37±8.9 nA, respectively. The estimated EC50 for the activation of this mutant receptor was 29.0 μM with a Hill coefficient of 1.3 (Figure 2).

The % mean (±s.e.m.) current responses to 1 μM ACh of receptors containing α1:Phe189Ser for oocytes injected with approximately 15 and 2–3 ng of RNA were 484±92 nA (n=8) and 20±3.8 nA (n=28), respectively. The estimated EC50 value for activation of AChRs containing α1:Phe189Ser mutant subunit was 42.1 μM with a Hill coefficient of 1.0. Although the peak current response at 1 mM ACh appears to be lower than for WT, the difference was not significant.

Similarly, the concentration–response relationship for receptors containing mutant α1:Phe189Ser + Pro194Ser subunit was obtained. The percentage mean (±s.e.m.) current response obtained for oocytes injected with approximately 15 ng of RNA was 702±99 nA (n=10), whereas for 2–3 ng RNA injected oocytes it was 38±8.2 nA (n=28). Thus levels of current responses for WT and mutant receptors to 1 μM ACh appeared to be similar suggesting that overall levels of expression might also be similar. The estimated EC50 value for this mutant receptor was 77.7 μM with a Hill coefficient of 0.90. Again there was an apparent reduction of the maximal current response associated with the replacement of phenylalanine by serine but this difference was also not significant.

The slightly decreased Hill slopes observed for α1:Phe189Ser and α1:Phe189Ser+Pro194Ser mutant receptors compared to WT receptors may not be significant. However, a lowered Hill slope can be the result of altered binding affinity or reduced gating efficiency or the presence of more than one type of receptor population. The possible presence of more than one type of receptor population has been partly tested by fitting the data to both single- and double-component models. In all cases, there was no improvement of fit with a two-component model, suggesting that a single-component fit is best (P>0.05, F-test).

Blockade of WT receptors by vecuronium

We used an electrophysiological method (see Methods; also Jenkinson 1996; Palma et al., 1996) to measure the microscopic association and dissociation rate constants of vecuronium binding to WT or mutant receptors.

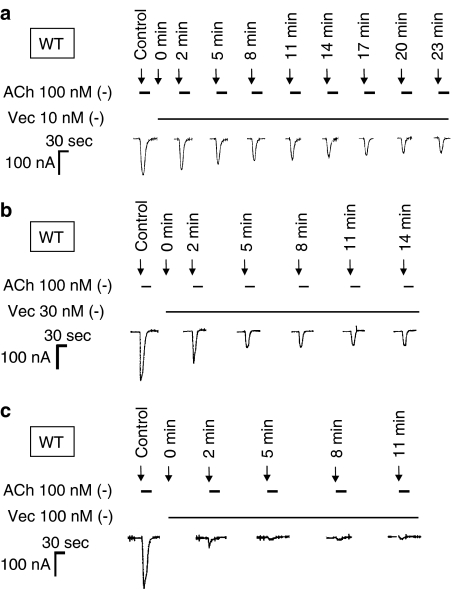

Figure 3a shows that continuously perfused vecuronium (10 nM) gradually inhibits ACh-induced (100 nM) inward current responses of receptors containing WT α1 subunits, suggesting progressive occupation of free receptors. Similarly, concentrations of 30 nM (Figure 3b) and 100 nM (Figure 3c) vecuronium were applied to separate cells and it is clear that the rate of onset of block increases as the concentration of vecuronium increases. Individual kon values for the progressive inhibition by vecuronium were estimated and their means (±s.e.m.) were then plotted against the corresponding concentration of vecuronium (Figure 4a). Again it can be seen that the on-rate of inhibition is proportional to the concentration of vecuronium applied. Thus, within the timescale of these experiments, for a relatively small ligand like vecuronium, changes in the rate of receptor occupancy closely follow changes in vecuronium concentration and can be estimated by this approach. From this plot, the slope yields the microscopic association rate constant, k+1, the y-intercept value gives the microscopic dissociation rate constant, k−1 and the ratio allows the KD value of vecuronium binding to the WT receptor to be calculated (see Table 2).

Figure 3.

Time course of vecuronium inhibition of the ACh responses of WT AChRs at different concentrations of vecuronium. Representative illustration of the inhibitory effect of vecuronium on inward current responses to applied ACh (100 nM) at mouse muscle AChRs continuously perfused with (a) 10 nM, (b) 30 nM and (c) 100 nM vecuronium. After several control applications of 100 nM ACh, an extracellular solution containing vecuronium was perfused through the chamber at t=0 min. Two minutes after the vecuronium perfusion had begun, vecuronium and 100 nM ACh were repeatedly coapplied to the oocyte at 3-min intervals. Vecuronium was continuously present during the intervals. The arrows indicate drug applications and the horizontal bars indicate the presence and final washout of drugs. Note that the on-rate of the block increases as the vecuronium concentration is increased.

Figure 4.

Dissociation rate of vecuronium binding appears to be more rapid for AChRs containing α1:Phe189 mutant subunits. The mean ‘on-rates' (±s.e.m.) for the inhibition of ACh (100 nM) responses was plotted against the corresponding vecuronium concentrations applied at AChRs containing (a) WT α1 subunits (n=3–6 separate oocytes at each point) and α1:Phe189Ser (n=3–6 separate oocytes at each point) and (b) α1:Pro194Ser (n=5–10 separate oocytes at each point) and α1:Phe189Ser +Pro194Ser (n=4 separate oocytes at each point). The slope of the plot (fitted by linear regression) represents the microscopic association rate constant (k+1), whereas the y-intercept value estimates the microscopic dissociation rate constant (k−1). The k+1 values (106 M−1 min−1) for WT, α1:Pro194Ser, α1:Phe189Ser and α1:Phe189Ser +Pro194Ser subunit containing AChRs were 1.1, 1.2, 1.4 and 1.6, respectively. The corresponding k−1 values ( × 10−2 min−1) were 8.2, 7.8, 18.0 and 13.0. The k+1 and k−1 values were greater for receptors containing the Phe189Ser mutation.

Determination of the rate of recovery of WT receptors from vecuronium block

Recovery experiments provide an alternative way of determining the dissociation rate constant of vecuronium binding to AChRs. The time constant for recovery from blockade (krec) is equivalent to the microscopic dissociation rate constant k−1. One advantage of estimating krec is that values obtained from individual oocytes can be compared statistically between groups of differently treated cells. Another is that KD values of vecuronium binding to AChRs can be estimated from the ratio krec/k+1. For both, WT and mutant receptors, the KD values calculated by the Jenkinson plots and the recovery approaches are in reasonable agreement (see Table 2).

Blockade of the current responses of receptors containing WT α1 subunits to 100 nM ACh by 200 nM vecuronium reached equilibrium within 6 min of perfusion with the antagonist. The recovery of the current responses was monitored during a period of continuous washing with normal ringer (Figure 5a). The recovery currents were expressed as a percentage of the initial control response to 100 nM ACh and then plotted against the time after commencement of washing (Figure 6a). Fitting of the data to single and double-component models was carried out, but as there was no improvement in fit when the data were fitted by a two-component model (P>0.05, F-test), a single-component model was used. The mean (±s.e.m.) krec value obtained from individual oocytes expressing WT receptors was 2.9 (±0.6) × 10−2 min−1 (n=4). This allowed the KD value of vecuronium binding to WT receptors to be calculated from the ratio of krec/k+1 , as shown in Table 2 (KD recovery method).

Figure 5.

Illustration of recovery responses from vecuronium block. The panels illustrate recovery from vecuronium block of inward current responses to 100 nM ACh at receptors containing (a) WT α1 subunits, (b) α1:Pro194Ser, (c) α1:Phe189Ser and (d) α1:Phe189Ser +Pro194Ser mutant subunits. About 1 min after the last control responses to applied ACh (100 nM), normal oocyte Ringer was replaced by vecuronium (200 nM) perfusion for 6 min. Agonist responses were almost completely inhibited during this treatment. The perfusate was then switched back to normal Ringer (trec=0 min). Thereafter recovery responses to control ACh were recorded. The arrows indicate drug application and the horizontal bars indicate the presence and final washout of drugs. Comparison of all the responses at 8 min illustrates that for receptors containing the Phe189Ser mutation, the agonist responses recover more quickly.

Figure 6.

Rapid rates of recovery from vecuronium blockade by AChRs containing α1:Phe189Ser mutant subunits. Individual recovery current responses were expressed as the % of the initial control response to 100 nM ACh. The mean pooled responses (±s.e.m.) were plotted as a function of the time after commencement of washing to remove vecuronium. Data were fitted to a single-exponential association equation. The krec values (min−1) of the pooled data shown in this figure were estimated to be (a) WT (3.0 × 10−2, n=4) and α1:Phe189Ser (10.0 × 10−2, n=8) and (b) α1:Pro194Ser (3.8 × 10−2, n=3) and α1:Phe189Ser +Pro194Ser (17.0 × 10−2, n=4). Note, that unlike the fit to pooled data in this figure, all krec estimates in Table 2 are the mean of separate recovery rates fitted in individual cells and are therefore marginally different.

α1:Pro194 is not essential for binding of vecuronium to AChRs

Increasing concentrations of vecuronium (3–100 nM) applied to α1:Pro194Ser receptor also inhibited 100 nM ACh-induced inward currents. The mean kon values were calculated and then plotted against the corresponding concentration of vecuronium (Figure 4b). Linear fitting of the data yielded a slope (k+1) and the corresponding y-intercept value (k−1). From these estimates, the calculated KD value of binding of vecuronium to the mutant receptors containing the α1:Pro194Ser subunit was calculated (Table 2).

As above, the mean % recovery responses were obtained (see Figure 5b for a representative trace). These responses were then plotted against the wash time to estimate the krec values (Figure 6b). The averaged krec value from vecuronium block of α1:Pro194Ser receptors was not significantly different from the krec values for WT receptors, neither was the KD value of vecuronium binding to these mutant receptors (Table 2).

α1:Phe189 does appear to be an important determinant of vecuronium binding to AChRs

As for WT receptors, the on-rates for inhibition of 100 nM ACh responses in the presence of different concentrations of vecuronium (10–100 nM) were measured for the receptors containing α1:Phe189Ser mutant subunits. The kon values were obtained as described earlier and plotted against the corresponding vecuronium concentrations (Figure 4a). From this plot, the estimated k+1, the k−1 value and the KD value of vecuronium binding to the receptors containing α1:Phe189Ser subunits was calculated (Table 2).

These data suggest that substitution of α1:Phe189 by serine had little effect upon the rate of association of vecuronium binding, but produced a moderate increase in the rate of dissociation of vecuronium when compared with WT. This apparent change in dissociation rate was mainly responsible for the higher calculated KD value (by the Jenkinson method) for the α1:Phe189Ser mutant.

A study of the rate of recovery from vecuronium-induced blockade of the α1:Phe189Ser receptors confirmed this impression (Figure 5c). The mean krec value for α1:Phe189Ser receptors obtained from the recovery plots (Figure 6a) was significantly faster than the recovery rate of WT receptors. This significant result again suggests that the measurements we have made of recovery rates over this relatively long timescale are sensitive enough to detect changes in the way drugs interact with mutated binding sites and are not unduly influenced by the biophysical properties of the oocyte system. The KD value of vecuronium binding to this mutant receptor calculated from the ratio of krec/k+1 was 78.6 nM.

Binding of vecuronium to α1:Phe189Ser + Pro194Ser receptors also shows an increased rate of antagonist dissociation

For the α1:Phe189Ser + Pro194Ser mutant receptor, the mean of the kon values in the presence of 100 nM vecuronium was 1. 71±0.07 min−1 (n=4). This was significantly different than the on-rates for both the WT (1.14±0.09, n=6) and α1:Pro194Ser containing receptors (1.25±0.1, n=10) but not for the α1:Phe189Ser receptors (1.47±0.06, n=6). Therefore the on-rates we have estimated can distinguish between different receptor subtypes. This would not be possible if the rate of access and equilibration of the drug, rather than the drug–receptor interactions of individual constructs, dominated the electrophysiological measurements we have made. The data in Figure 4b yielded k+1 and k−1 values, and from these estimates the KD value of vecuronium binding to the double-mutant receptors was calculated (Table 2).

The results shown in Figures 5d and 6b provided the estimated rate of recovery from vecuronium-induced block of α1:Phe189Ser + Pro194Ser subunit containing AChRs. The rate of vecuronium dissociation from this double mutant was significantly faster than from both WT and α1:Pro194Ser receptors. However, this recovery from vecuronium blockade of the double-mutant receptor was not significantly faster than the recovery of the α1:Phe189Ser receptors (Table 2).

Discussion

The current study combines two approaches to study ligand–receptor interactions of nicotinic AChRs. First, we have developed a binding assay in TE671 cells, which can enable the rapid screening of novel nicotinic ligands. We have then used electrophysiology and mutagenesis to examine how individual amino acids contribute to the actions of such ligands.

The TE671 ligand-binding assay provides a fast and efficient method of screening a large number of compounds with NMB actvity

The KD estimate for [125I]α-Bungarotoxin obtained from saturation binding experiments was 0.7 nM. This is in good agreement with previous studies using intact TE671 cells (Syapin et al., 1982, 1.4 nM; and TE671 membrane fractions (Lukas, 1986, 2 nM and 40 nM). On the basis of this, a concentration of 0.1 nM was chosen for the inhibition studies. However a preliminary time-course study (unpublished results) showed that although the binding to TE671 cells approaches equilibrium (>90%) after 2 h it does not quite reach it. Thus a true affinity constant cannot be calculated from the data as equilibrium is not fully established. Nonetheless, 2 h was considered to be a sufficient incubation period for the evaluation of IC50 values as part of a large-scale screen for neuromuscular AChR-binding activity.

The relative values of the IC50 values thereby obtained appear to correlate with the corresponding relative clinical potency data in man (see Table 1). Mivacurium, vecuronium and pancuronium were more potent than rapacuronium, rocuronium, suxamethonium, gallamine and diadonium. d-TC seemed relatively more potent in the TE671 assay than in man, whereas rapacuronium and atracurium exchanged places. Perhaps the differences in relative potency seen in the two systems are due to the fact that TE671 cells contain the fetal AChR subunit combination, (α1β1γδ; Luther et al., 1989) as opposed to the adult form (α1β1ɛδ; MacLennan et al., 1993), which provided the clinical data. None the less there is general agreement between the human clinical data and the TE671-binding data. There is also reasonable agreement with a recent electrophysiological study of the responses of adult human muscle AChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes to 10 μM ACh (Jonsson et al., 2006). IC50 values for mivacurium, d-TC, pancuronium and vecuronium were in the range 3.69–18.73 nM. However IC50 values for atracurium (96.65 nM) and rocuronium (13.76 nM) were lower, although still correlating well with the adult clinical data. Overall, as an assay for predicting compounds that might be active in humans, the TE671-binding assay appears to be very successful and, indeed, studies using this assay were among the first, which confirmed the therapeutic potential of rapacuronium.

The function of nicotinic receptors is slightly altered, but not lost, if phenylalanine 189 and proline 194 of the α1 subunit are replaced by serine

To explore further ligand–receptor interactions in muscle AChRs, we used an electrophysiological approach to test the reliance of receptor function and pharmacology upon the specific presence of Phe at α1:189 and Pro at α1:194 in the mouse α1 subunit.

The WT and mutant α1 subunit containing receptors expressed well, producing robust ACh-evoked currents. The ACh EC50 value for WT α1 subunit containing receptors of 23.6 μM is in good agreement with previously reported estimates for foetal mouse muscle AChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes (20.3±0.4 μM; O'Leary and White, 1992; 19.3±0.6 μM; Aylwin and White, 1994). For all the mutations of α1:Phe189 and α1:Pro194 we made, the EC50 values were still in this same order of the micromolar range. Hence if such point mutations were to occur in vivo, one might expect neurotransmission to be preserved. This functional resilience is remarkable. Substitution of a sterically constraining Pro residue usually has deleterious effects on both the structure (Yohannan et al., 2004a) and function (Befort et al., 2001; Weyand et al., 2002) of proteins. For example, ɛ: Pro121Leu in AChRs causes a reduced probability of channel opening (Ohno et al., 1996). However, in adult muscle receptors activated by choline, mutation of β1:Phe15′Ile in transmembrane domain II causes a 10-fold reduction in the closing rate, a 2.5-fold enhancement of the opening rate and a 28-fold increase in the diliganded gating equilibrium constant (Spitzmaul et al., 2004). A missense mutation involving α4:Ser248Phe mutation in the transmembrane domain 2 of human AChRs causes autosomal-dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy (Steinlein et al., 1995).

The question therefore arises as to how Phe and Pro can be replaced in the ligand-binding region of AChRs without causing a major change in agonist activation. One explanation is that the recently described evolutionary repair hypothesis of Yohannan et al. (2004b) for G-proteins could also apply to hydrophilic regions of ligand-gated ion channels. They observed that three Pro residues in bacteriorhodopsin could be changed to Ala with minimal structural effects. They hypothesized that an ancestral mutation to Pro introduced a kink within the transmembrane helices of the protein. However, during evolution, additional mutations elsewhere in the protein stabilized its new architecture so that it later became possible to replace Pro by Ser and still maintain the structural kinks. Therefore in the present study, the overall preservation of the ability of ACh to activate mouse muscle AChRs when Phe189 and Pro194 are mutated may indicate that their architectural contribution to function has been sufficiently ‘reinforced'. This evolutionary pressure would not apply to the interaction of the antagonist vecuronium with AChRs, for which the set of interacting amino acids could also be partially different to those involved in mediating the effects of ACh. Nonetheless, where a protein is uniquely responsible for a life-enabling process (in this case initiating muscle contraction during breathing), intramolecular adaptations, which provide ‘fail safe' stabilization of the functional architecture might enjoy a selection advantage. Such adaptations may be more common in phylogenetically more ancient proteins carrying out vital functions.

Vecuronium binding to WT and mutant AChRs

For all the receptor constructs investigated, the on-rates of vecuronium binding closely followed concentration (Figures 3 and 4) and revealed significant differences among the various mutants at 100 nM. The recovery rates were also able to show significant differences among the mutants (see Table 2). Therefore, this electrophysiological approach is useful for elucidating the relative contribution of particular amino acids to the pharmacological properties of AChRs.

KD values of vecuronium binding to WT receptors calculated by the Jenkinson (75.0 nM) and recovery approaches (26.4 nM) were in reasonable agreement with each other. They are also of the same order as the estimates of 10.3 nM made by Son et al. (1981) from dose–ratio experiments with guinea pig lumbrical muscle AChRs, 15 nM (Green, 1987) calculated from Schild plots of chick biventer cervicis responses and the IC50 value of 40 nM obtained in the binding assay here. Dose–ratio experiments in frog cutaneous pectoris muscle (Min et al., 1992) yielded an estimated KD value of 230 nM. Recovery rates from block were variable but somewhat faster in the latter study, but mM concentrations of antagonist (perhaps producing some nonspecific block), very different methods of measurement and, of course, a different species was used. All these KD values are greater than the IC50 values reported previously for vecuronium inhibition of 1 μM ACh responses of embryonic mouse muscle AChRs expressed in oocytes (1.9 nM, Kindler et al., 2000; 7.6 nM, Paul et al., 2002), and for similarly measured (10 μM ACh) adult human receptors (10.7 nM, Jonsson et al., 2006). Although KD and IC50 values cannot be directly compared, the results suggest that for embryonic mouse muscle AChRs, the presence of our estimate in the lower range of KD values is reasonable. It may be that in preparations, which can be more rapidly perfused, on-rates and recovery rates may be slightly faster. Nonetheless, in absolute terms the electrophysiological approach used here has yielded acceptable KD values for the action of vecuronium on embryonic WT mouse-muscle receptors.

Kinetic parameters were also estimated for the mutant receptors (see Table 2). Compared to WT receptors, the α1:Pro194Ser substitution had no apparent effect on the overall KD value or krec estimate for vecuronium blockade. Thus, α1:Pro194 may not be directly involved in binding of vecuronium to AChRs. However, both mutant receptors containing the α1:Phe189Ser mutation showed significantly faster dissociation rates for vecuronium binding when compared with WT receptors, suggesting that α1:Phe189 contributes structurally to the binding site of vecuronium. The studies also show that this electrophysiological approach in oocytes is sensitive enough to discriminate between the kinetic properties of at least some mutant constructs.

Proposed model of vecuronium binding to AChRs

The cation-π bonding of the aromatic side chain of amino acid residues such as Tyr, Phe or Trp with quaternary ion centres is well established in structural biology (Zhong et al., 1998; Gallivan and Dougherty, 1999). For the α1:Phe189Ser mutation, any cation–π interaction is destroyed and vecuronium may be less strongly anchored in the binding site. Dissociation would then become more favourable. Supporting this idea we have found that krec values are significantly increased for α1:Phe189Ser containing mutants, whereas k+1 appears to remain broadly the same. Therefore, it seems more likely that α1:Phe189 stabilizes binding of vecuronium once it has entered the binding pocket, rather than providing a steric hindrance to binding and slowing its association.

This theory is supported by observations on other aromatic residues in the same region of the binding site. Fu and Sine (1994) reported that α1:Tyr198 and γ-Tyr117 in mouse muscle AChRs were critical determinants of interactions with the quaternary nitrogen of dimethyl-d-tubocurarine, pancuronium and gallamine. For all these ligands, substitution of Tyr in either position with another aromatic residue (Phe or Trp) maintained affinity comparable to the WT receptors. In contrast, Ser substitutions for Tyr-reduced affinity. For pancuronium, the lowest affinities were obtained when positively charged Arg was incorporated in place of Tyr. Therefore in these experiments, the presence of any aromatic residue appears to enhance the binding of vecuronium-like compounds. Although these are not the same sites as the α1:Phe189 mutated here, they do suggest that aromatic residues can contribute to NMBA binding in mouse AChRs.

Interestingly, a complementary study in which the ligand (rather than the receptor) was altered was carried out by Bowman et al. (1988). Sequential removal of two potentially cationic, quaternary ACh-like moieties from positions 3 and 17 decreased the potency of vecuronium analogues but increased the speed of onset of chick tibialis muscle blockade with a simultaneous decrease in the duration of action. Bowman et al. (1988) suggested that the duration of action of vecuronium analogues was inversely related to their potency. Even though pharmacokinetic factors need to be considered and the chick receptor has tyrosine at α1:189, it seems possible that this study and our approach are examining different aspects of a common interaction.

Conclusion

A binding assay in TE671 cells provided a method for the rapid identification of agents, which act at nicotinic AChRs. Additional electrophysiological studies showed that the function of AChRs is remarkably resilient despite nonconservative substitutions in the agonist binding site. This might be explained by evolutionary ‘re-inforcement' of the binding site architecture. The results also suggest that α1:Phe189, but not α1:Pro194, is a significant molecular determinant of the rate of vecuronium dissociation from mouse muscle AChRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Overseas Research Award Committee, Strathclyde International Scholarship (PGP) and Strathclyde Research Development Fund RDF 1204 (JGC) for funding the project. We would also like to thank Dr Christopher Prior for generous donation of vecuronium for this study.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AChRs

nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- DMT

dimethyl-d-tubocurarine

- d-TC

d-tubocurarine

- NMBAs

neuromuscular blocking agents

- WT

wild type

Conflict of interest

David Hill and Eleanor Pow are employees of Organon who produce vecuronium.

References

- Arias HR. Localization of agonist and competitive antagonist binding sites on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neurochem Int. 2000;36:595–645. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(99)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylwin ML, White MM. Ligand–receptor interactions in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor probed using multiple substitutions at conserved tyrosines on the α subunit. FEBS Lett. 1994;349:99–103. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00649-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartowski RR. Recent advances in neuromuscular blocking agents. Am. J. Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:S14–S17. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Befort K, Filliol D, Decaillot FM, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Hoehe MR, Kieffer BL. A single nucleotide polymorphic mutation in the human μ-opioid receptor severely impairs receptor signalling. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3130–3137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount P, Merlie JP. Molecular basis of the two non-equivalent ligand-binding sites of the muscle nicotinic receptor. Neuron. 1989;3:349–357. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter J, Connolly J, Deneris E, Goldman D, Heinemann S, Patrick J. Functional expression of two neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors from cDNA clones identifies a gene family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:7763–7767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman WC, Rodger IW, Houston J, Marshall RJ, McIndewar I. Structure:action relationships among some desacetoxy analogues of pancuronium and vecuronium in the anesthetized cat. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunatian AA.Neuromuscular blocking agents of different chemical structure New Neuromuscular Blocking Agents 1986Springer; Berlin; 567–575.DA Karkevich (ed) [Google Scholar]

- Connolly JG, Boulter J, Heinemann S. alpha4-2beta2 and other nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes as targets of psychoactive and addictive drugs. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;105:657–666. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb09035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RL, Shrimpton AE, Holohan PD, Bradshaw C, Feiglin D, Collins GH, et al. Familial dementia caused by polymerization of mutant neuroserpin. Nature. 1999;401:376–379. doi: 10.1038/43894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehmann HC, Gross U, Epe M. A new mutation in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1-α gene (P224S) in a newly discovered German family with maturity-onset diabetes of the young 3 (MODY 3). Family members carry additionally the homozygous I27L amino acid polymorphism in the HNF1α gene. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2004;112:84–87. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu DX, Sine SM. Competitive antagonists bridge the alpha–gamma subunit interface of the acetylcholine receptor through quaternary ammonium–aromatic interactions. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26152–26157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldes FF, Nagashima H, Nguyen HD, Schiller WS, Mason MM, Ohta Y. The neuromuscular effects of ORG9426 in patients receiving balanced anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:191–196. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallivan JP, Dougherty DA. Cation-π interactions in structural biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9459–9464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland CM, Foreman RC, Chad JE, Holden-Dye L, Walker RJ. The actions of muscle relaxants at nicotinic acetylcholine receptor isoforms. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;357:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Riganti L, Vailati S, Clementi F. Brain neuronal nicotinic receptors as new targets for drug discovery. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:407–428. doi: 10.2174/138161206775474486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramstad L, Lilleaasen P. Dose–response relationship atracurium, Org NC45 and Pancuronium. Br J Anaestheth. 1982;75:191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Green KL.Studies on the mechanisms of action of some newly synthesised quaternary steroidal neuro-muscular blocking of compounds 1987Thesis, University of Strathclyde; Ph.D. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevandra Martyn JA, Fukushima Y, Chon JY, Yang HS. Muscle relaxants in burns, trauma and critical illness. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2006;44:123–143. doi: 10.1097/00004311-200604420-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson DH.Classical approaches to the study of drug-receptor interactions Textbook of Receptor Pharmacology 1996CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL; 3–62.In: Foreman JC and Johansen T (Eds)1st edn. [Google Scholar]

- Jou SB, Chang LI, Pan H, Chen PR, Hsiao KM. Novel CLCN1 mutations in Taiwanese patients with myotonia congenita. J Neurol. 2004;251:666–670. doi: 10.1007/s00415-004-0383-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson M, Gurley D, Dabrowski M, Larsson O, Johnson EC, Eriksson LI. Distinct pharmacologic properties of neuromuscular blocking agents on human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:521–533. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindler CH, Verotta D, Gray AT, Gropper MA, Yost CS. Additive inhibition of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by corticosteroids and the neuromuscular blocking drug vecuronium. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:821–832. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200003000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas RJ. Characterization of curaremimetic neurotoxin binding sites on membrane fractions derived from the human medulloblastoma clonal line, TE671. J Neurochem. 1986;46:1936–1941. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1986.tb08516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther MA, Schoepfer R, Whiting P, Casey B, Blatt Y, Montal MS, et al. A muscle acetylcholine receptor is expressed in the human cerebellar medulloblastoma cell line TE671. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1082–1096. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-03-01082.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan C, Beeson D, Vincent A, Newsom Davis J. Human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha-subunit isoforms: origins and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5463–5467. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.23.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min JC, Bekavac I, Glavinovic MI, Donati F, Bevan DR. Iontophoretic study of speed of action of various muscle relaxants. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:351–356. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199208000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Wang HL, Milone M, Bren N, Brengman JM, Nakano S, et al. Congenital myasthenic syndrome caused by decreased agonist binding affinity due to a mutation in the acetylcholine receptor epsilon subunit. Neuron. 1996;17:157–170. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary ME, White MM. Mutational analysis of ligand-induced activation of the Torpedo ACh receptor. J Biol Chem. 1992;297:8360–8365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul M, Kindler CH, Fokt RM, Dresser MJ, Dipp NC, Yost CS. The potency of new muscle relaxants on recombinant muscle-type acetylcholine receptors. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:597–603. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200203000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma E, Bertrand S, Binzoni S, Bertrand D. Neuronal nicotinic α7 receptor expressed in Xenopus oocytes presents five putative binding sites for methyllycaconitine. J Physiol. 1996;491:151–161. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen SE, Cohen JB. d-Tubocurarine binding sites are located at alpha-gamma and alpha-delta subunit interfaces of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2785–2789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarese JJ, Ali HH, Basta SJ, Embree PB, Scott RP, Sunder N, et al. The clinical neuromuscular pharmacology of mivacurium chloride (BW B1090U). A short-acting nondepolarizing ester neuromuscular blocking drug. Anesthesiology. 1988;68:723–732. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198805000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepfer R, Luther MA, Lindstrom J. The human medulloblastoma cell line, TE671, expresses a muscle-like acetylcholine receptor. FEBS Lett. 1988;226:235–240. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks CA, Walker JS, Ramzan MI, Triggs EJ. Dose–response curves for four neuromuscular blockers using continuous i.v. infusion. Br J Anaesthesia. 1981;53:627–633. doi: 10.1093/bja/53.6.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Donati F, Bevan DR. Potency of succinylcholine at the diaphragm and at the adductor pollicis muscle. Anesth Analg. 1988;67:625–630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son SL, Waud BE, Waud DR. A comparison of the neuromuscular blocking and vagolytic effects of ORG NC 45 and pancuronium. Anesthesiology. 1981;55:12–18. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzmaul G, Corradi J, Bouzat C. Mechanistic contributions of residues in the M1 transmembrane domain of the nicotinic receptor to channel gating. Mol Membr Biol. 2004;21:39–50. doi: 10.1080/09687680310001607341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinlein OK, Mulley JC, Propping P, Wallace RH, Phillips HA, Sutherland GR, et al. A missense mutation in the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 subunit is associated with autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy. Nat Genet. 1995;11:201–203. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton MR, Reeves BR, Cooper CS. Misidentified Cell. Nature. 1989;337:311–312. doi: 10.1038/337311c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syapin PJ, Salvaterra PM, Engelhardt JK. Neuronal-like features of TE671 cells: presence of a functional nicotinic cholinergic receptor. Brain Res. 1982;321:365–377. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90373-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagaki Y, Futamura M, Yamaguchi K, Aoki S, Takahashi T, Saji S. Alternations of the PPP2R1B gene located at 11q23 in human colorectal cancers. Gut. 2000;47:268–271. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanik DL, Surewicz WK. Disease-associated F198S mutation increases the propensity of the recombinant prion protein for conformational conversion to scrapie-like form. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49065–49070. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyand M, Schlichting I, Herde P, Marabotti A, Mozzarelli A. Crystal structure of the βser178 to pro mutant of tryptophan synthase. A ‘knock-out' allosteric enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10653–10660. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierda JM, Beaufort AM, Kleef UW, Smeulers NJ, Agoston S. Preliminary investigations of the clinical pharmacology of three short-acting non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents, Org 9453, Org 9489 and Org 9487. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:213–220. doi: 10.1007/BF03009833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohannan S, Faham S, Yang D, Whitelegge JP, Bowie JU. The evolution of transmembrane helix kinks and the structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004a;101:959–963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306077101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohannan S, Faham S, Yang D, Whitelegge JP, Bowie JU. The evolution of transmembrane helix kinks and the structural diversity of G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004b;101:959–963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306077101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost CS, Winegar BD. Potency of agonists and competitive antagonists on adult- and fetal-type nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1997;17:35–50. doi: 10.1023/A:1026325020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zehelein J, Thomas D, Khalil M, Wimmer AB, Koened M, Licka M, et al. Identification and characterisation of a novel KCNQ1 mutation in a family with Romano–Ward syndrome. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1690:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong W, Gallivan JP, Zhang Y, Li L, Lester HA, Dougherty DA. From ab initio quantum mechanics to molecular neurobiology: a cation-π binding site in the nicotinic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12088–12093. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]