Abstract

The desmethoxy analogue of the cytotoxic, cyclic depsipeptide callipeltin B was synthesized to evaluate the role of its β-MeOTyr residue. The IC50 of desmethoxycallipeltin B, in which the β-MeOTyr residue was replaced by D-Tyr, against HeLa cells was found to be 128±10 µM in an MTT assay, compared to 98±5 µM for the natural product itself. The roughly comparable cytotoxiticities suggest that the cytotoxicity of callipeltin B does not arise through the formation of a quinone methide intermediate.

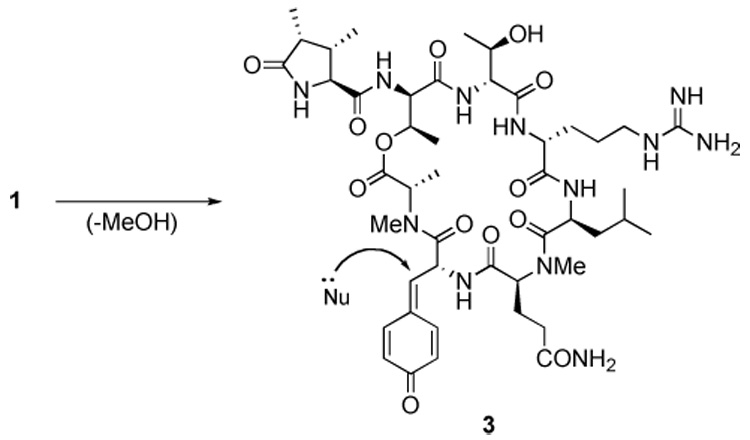

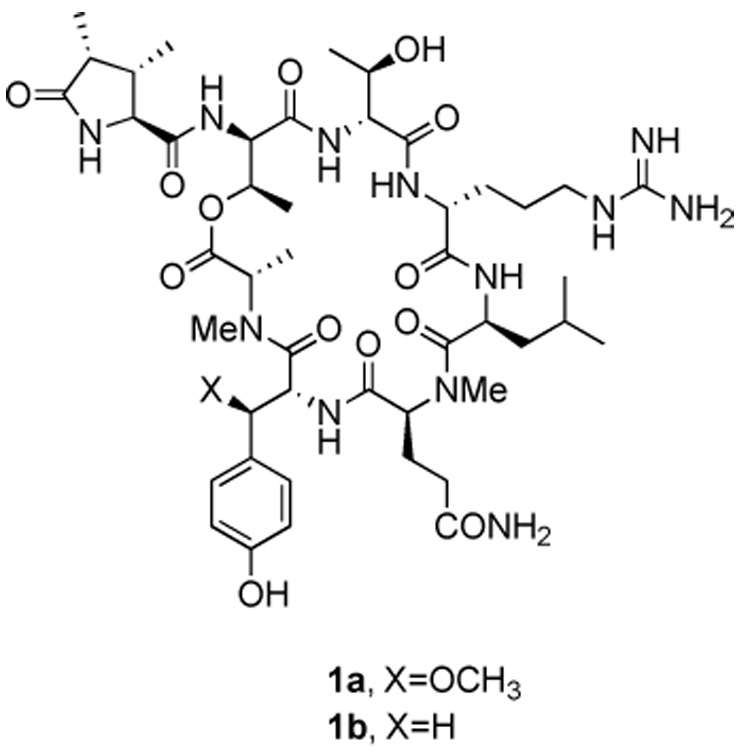

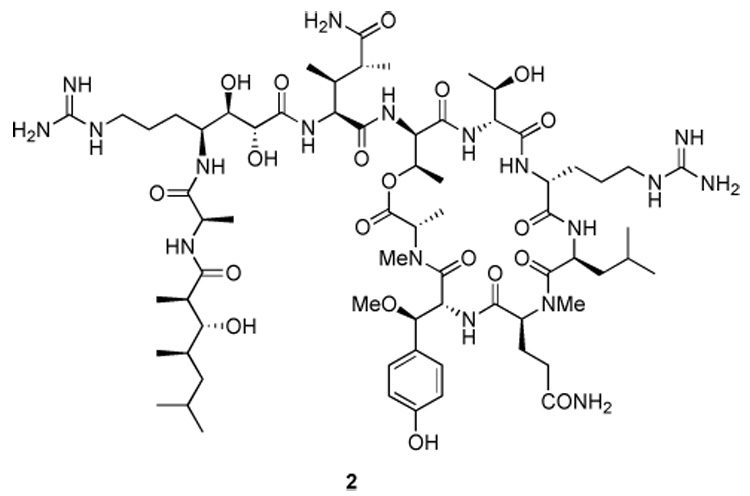

Callipeltin B (1a) and its congener callipeltin A (2), are cyclic depsipeptides isolated from the lithistid marine sponge callipelta sp. by Minale and co-workers. Both molecules were reported to exhibit broad-spectrum cytotoxicity against various tumor cell lines.1,2 Additionally, the related cyclic depsipeptides papuamides A-D3 and neamphamide A4 were isolated from other marine sponges and also shown to exhibit broad-spectrum cytotoxicity against tumor cell lines. Because all of these cyclic depsipeptides contained the novel amino acid β-methoxytyrosine (β-MeOTyr), speculation arose as to whether the cytotoxicity of 1a resulted from elimination of methanol from β-MeOTyr to form a reactive quinone methide intermediate (3, Scheme 1) that subsequently reacted with a biological nucleophile.

Scheme 1.

Formation and reaction of a putative quinone methide intermediate 3.

Such an idea received indirect support during the recent synthesis of 1a, when acid deprotection of 1a resulted in the formation of a side-product that MALDI-MS showed had lost methanol.5 To test such a hypothesis, desmethoxycallipeltin (1b), in which the β-MeOTyr residue of 1a was replaced by a D-Tyr, was synthesized and assayed for cytotoxicity.

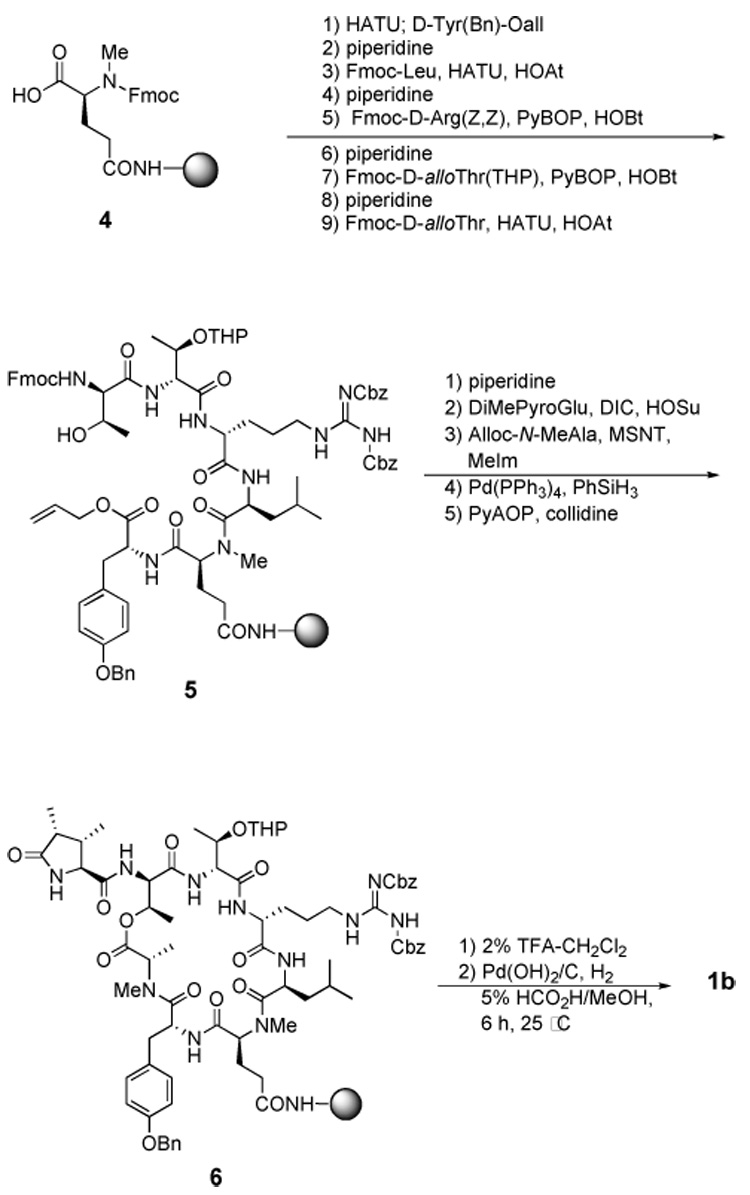

Herein we report the synthesis of 1b using the same strategy used for the synthesis of 1a (Scheme 2).5 d-Tyr(Bn) allyl ester was synthesized in two steps from commercially available Boc-d-Tyr(Bn). All the other residues were either commercially available or had been previously synthesized in our group during the synthesis of 1a.5,6 As before, the Sieber amide resin7 was acylated with the MeGln residue of 1b to afford the intermediate 4. All deprotection and coupling reactions were monitored by cleavage of a 1–2 mg sample of resin using 2% TFA-CH2Cl2 followed by analysis using of the crude cleavage mixture using reverse phase HPLC and MALDI-MS.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of desmethoxycallipeltin B (1b)

The macrocyclized product 6 was cleaved from the resin with 2% TFA-CH2Cl2 and the crude cleavage product was purified by RP-HPLC to afford 2.6 mg of purified 2 in 11% overall yield. The identity of 1b was confirmed by MALDI-MS and ¹H NMR. The homogeneity of the synthetic 1b was confirmed by RP-HPLC and ¹H NMR.

With synthetic 1b in hand, we assayed 1b for cytotoxicity alongside synthetic 1a, which served as the control. The MTT fluorogenic assay8,9 was chosen as the method for quantifying cytotoxicity, and it was performed with DMEM-supplemented HeLa cells. Analysis of the dose-response data obtained from the assay afforded IC50 values for both 1a and 1b. The mean IC50 values obtained from duplicate assays were 98±5 µM for 1a and 128±10 µM for 1b.

Although 1b is slightly less cytotoxic than 1a, the small difference in IC50 values of 1a and 1b is not what one would expect if the β-MeOTyr residue were essential for cytotoxicity. This result strongly suggests that a quinone methide intermediate is not responsible for the cytotoxicity of 1a. In light of the recent report that the closely related cyclic depsipeptide callipeltin A is a sodium ionophore,10 a reasonable alternative source of cytotoxicity could be the ability of both 1a and 1b to act as sodium ionophores. This hypothesis is now being actively investigated in our laboratory. The small difference in activity between 1a and 1b that is observed is possibly attributable to a conformational change that results from removal of the methoxy substituent of β-MeOTyr. Indirect support for such an explanation is provided by a comparison of the ROESY spectra of 1a and 1b, which show noticeable differences.11

In summary, an analogue of callipeltin B that lacks a β-MeOTyr residue has been synthesized and its cytotoxic effect on HeLa cells quantified using an MTT assay. Substitution of D-Tyr for β-MeOTyr does not substantially affect the cytotoxicity of callipeltin B, leading to the conclusion that a quinone methide intermediate is unlikely to be the principal source of the cytotoxicity of callipeltin B. Studies are ongoing in our laboratories to further elucidate the roles played by the various non-proteinogenic amino acids in 1a and to further explore the mode of action of 1a and related natural products.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Stuctures of callipeltin B (1a) and desmethoxycallipeltin B (1b)

Figure 2.

Structure of callipeltin A (2).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. John Harwood with NMR studies. We also thank the National Institutues of Health (AI-50888) and the Gebrüder Sulzbach’sche Familienstiftung for financial support of this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.D'Auria MV, Zampella A, Paloma LG, Minale L. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:9589. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zampella A, D'Auria MV, Paloma LG, Casapullo A, Minale L, Debitus C, Henin Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:6202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford PW, Gustafson KR, McKee TC, Shigematsu N, Maurizi LK, Pannell LK, Williams DE, Silva EDD, Lassota P, Allen TM, Soest RV, Andersen RJ, Boyd MR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:5899. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oku N, Gustafson KR, Cartner LK, Wilson JA, Shigematsu N, Hess S, Pannell LK, Boyd MR, McMahon JB. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:1407. doi: 10.1021/np040003f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishnamoorthy R, Vazquez-Serrano LD, Turk JA, Kowalski JA, Benson AG, Breaux NT, Lipton MA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15392. doi: 10.1021/ja0666250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Acevedo CM, Kogut EF, Lipton MA. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:6353. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sieber P. Tet. Lett. 1987;28:2107. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milhaud PG, Marcy P, Lebleu B, Leserman L. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1989;987:15. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez NS, Konigsberg M. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 2006;34:209. doi: 10.1002/bmb.2006.49403403209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trevisi L, Cargnelli G, Ceolotto G, Papparella I, Semplicini A, Zampella A, D'Auria MV, Luciani S. Biochem. Pharm. 2004;68:1331. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krishnamoorthy R. unpublished results. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.