Abstract

Background and purpose:

In terms of postjunctional α2-adrenoceptors in the pulmonary circulation, no evidence is available with regard to the receptor subtypes mediating vasoconstriction. Therefore, we characterized the α2-adrenoceptor subtypes mediating contraction in isolated porcine pulmonary veins.

Experimental approach:

α-adrenoceptor-mediated vasoconstriction was studied using a tissue bath protocol. mRNA profile and relative quantification of α2-adrenoceptor subtypes were determined in porcine pulmonary veins using reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and real-time PCR.

Key results:

In porcine pulmonary veins, noradrenaline, phenylephrine (α1-adrenoceptor agonist), UK14304 and clonidine (α2-adrenoceptor agonists) caused concentration-dependent contractions. The rank order of agonist potency was: NA≈UK14304≈clonidine > phenylephrine. UK14304 responses were antagonised by MK912 (noncompetitive antagonist parameter pD'2: 10.1), rauwolscine (pKB: 9.5), yohimbine (pKB: 9.1), WB4101 (pKB: 8.7), ARC239 (pKB: 7.5), prazosin (pKB: 7.1) and BRL44408 (pKB: 7.0). Antagonist potencies fitted best with radioligand binding data (pKi) at the human recombinant α2C-adrenoceptor (r2 = 0.96, P = 0.0001). Correlation with α2B-adrenoceptors was lower (r2 = 0.74, P > 0.01) and no correlation was obtained with α2A-adrenoceptors. Moreover, RT-PCR studies in porcine pulmonary veins showed mRNA signals for α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors, but not for α2B-adrenoceptors, whilst real-time PCR studies indicated a prominent expression of α2C-adrenoceptor mRNA.

Conclusions and Implications:

Postjunctional α2C-adrenoceptors mediated contraction in porcine pulmonary veins. α1-Adrenoceptors also seem to be present in this tissue. Since α2-adrenoceptor responsiveness is increased when pulmonary vascular tone is elevated, α2C-adrenoceptor antagonists may be beneficial in diseases such as pulmonary hypertension or congestive heart failure.

Keywords: α2-adrenoceptors, α-adrenoceptor antagonists, porcine pulmonary veins, UK14304, vasoconstriction

Introduction

Postjunctional vascular α1- and α2-adrenoceptors have been shown to coexist in systemic arterial and venous circulatory beds mediating vasoconstriction (Docherty, 1998; Guimarãez and Moura, 2001). On the basis of conjunction of structural, transductional and operational criteria, α1-adrenoceptors have been classified into α1A-, α1B- and α1D-adrenoceptor subtypes, whereas α2-adrenoceptors have been classified into α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptor subtypes (Bylund et al., 1994). Whereas postjunctional α1A- and α1D-adrenoceptor subtypes are mainly involved in the contractions induced by α1-adrenoceptor agonists, there is relatively little evidence available as to the subtypes mediating vascular contractions via postjunctional α2-adrenoceptors (Docherty, 1998; Guimarães and Moura, 2001). In this respect, several studies have demonstrated vasoconstriction mediated by (i) α2A-adrenoceptors in canine saphenous vein and mesenteric artery (MacLennan et al., 1997; Paiva et al., 1999) as well as in porcine ciliary artery (Wikberg-Matsson and Simonsen, 2001); (ii) α2C-adrenoceptors in human saphenous vein (Gavin et al., 1997) and (iii) both α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors in porcine nasal mucosa strips (Corboz et al., 2003) and in the canine external carotid arterial bed (Willems et al., 2001a, 2001b).

In vivo and in vitro studies suggest that the pulmonary circulation is also endowed with both postjunctional α1- and α2-adrenoceptors which mediate vasoconstriction (Hyman and Kadowitz, 1985; Shebuski et al., 1986, 1987; Ohlstein et al., 1989). Interestingly, α2-adrenoceptor responsiveness is selectively enhanced when the pulmonary vascular tone is elevated (Hyman and Kadowitz, 1986; Shebuski et al., 1987). However, no data are available on the α2-adrenoceptor subtype(s) mediating contraction in pulmonary blood vessels.

Pronounced α2-adrenoceptor-mediated contractile responses in veins, but not in arteries, have previously been described in the canine pulmonary circulation. Thus, it has been hypothesized that pulmonary vascular α2-adrenoceptors may be located preferentially on the venous side of the pulmonary circulation (Shebuski et al., 1987; Ohlstein et al., 1989). Consequently, this study has focused on the characterization of the postjunctional α2-adrenoceptor subtype(s) in pulmonary veins. In contrast to peripheral veins, pulmonary veins have a specific feature because they carry oxygenated blood. However, pulmonary veins macroscopically have a thinner wall thickness because they are exposed to lower blood pressure than the pulmonary arteries. We used porcine veins to examine the pharmacological characteristics of α2-adrenoceptor-mediated contraction because (i) pigs and humans share anatomical, physiological, histological and biochemical similarities (Pound and Houpt, 1978); (ii) pigs are favoured as potential donors for xenotransplantation (Platt, 2001); and (iii) the pig α2-adrenoceptor subtypes are pharmacologically more related to those of humans than to those of rodents (Wikberg-Matsson et al., 1995). In tissue bath studies, we used α-adrenoceptor agonists such as noradrenaline (a non-selective adrenoceptor agonist), phenylephrine (α1-adrenoceptor agonist), clonidine and brimonidine tartrate (UK14304) (both α2-adrenoceptor agonists). In addition, we examined the blocking properties of the antagonists 2-[(4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methyl]-2,3-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-isoindole maleate (BRL44408) (α2A; Young et al., 1989), (2S-trans)-1,3,4,5′,6,6′,7,12b-octahydro-1′,3′-dimethyl-spiro[2H-benzofuro[2,3-a]quinolizine-2,4′(1′H)-pyrimidin]-2′(3′H)-one hydrochloride (MK912) (α2C; Uhlén et al., 1992), 2-[2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethyl]-4,4-dimethyl-1,3-(2H,4H)-isoquinolindione dihydrochloride (ARC239) (α2B/2C; Bylund et al., 1988), 2-(2,6-dimethoxyphenoxyethyl)aminomethyl-1,4-benzodioxane hydrochloride (WB4101) (α1A/α2C; Uhlén et al., 1994) as well as prazosin (α1, α2B/α2C; Bylund et al., 1994), yohimbine and rauwolscine (non-selective α2-adrenoceptor antagonists; Table 1) against the contractile response to UK14304. In addition, we used both reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and real-time polymerase chain reaction techniques to identify and to quantify the mRNA being expressed in porcine pulmonary veins. Our results suggest that UK14304-induced vasoconstriction in porcine pulmonary veins is mediated by postjunctional α2C-adrenoceptors. Functional studies rule out the involvement of α2A-adrenoceptors, both functional studies and RT-PCR exclude the presence of the α2B-subtype and real-time PCR suggests the predominant occurrence of the α2C-subtype in porcine pulmonary veins.

Table 1.

Binding affinities (pKi values) of antagonists for α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors and antagonist affinity estimates (pKB values) against the contractile response to UK14304 in porcine pulmonary veins

| Antagonists | α2A (pKi) | α2B (pKi) | α2C (pKi) | Pulmonary vein (pKB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARC239 | 5.88 | 7.71 | 7.50 | 7.48±0.03 (4–7) |

| BRL44408 | 8.25 | 6.19 | 6.82 | 7.02±0.08 (4–8) |

| MK912 | 8.90 | 8.87 | 10.07 | 10.05±0.04 (5)a |

| Rauwolscine | 8.43 | 8.34 | 9.11 | 9.53±0.08 (4)b |

| Prazosin | 5.65 | 6.94 | 7.24 | 7.06±0.06 (4) |

| Yohimbine | 8.43 | 7.87 | 8.52 | 9.09±0.05 (4–5) |

| WB4101 | 7.84 | 7.11 | 8.50 | 8.65±0.05 (4–6) |

Binding affinities (cloned human α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors expressed in Cos-7 cells; [3H]MK912), data from Uhlén et al. (1994). The slopes of the Schild plots were as follows: ARC239, 0.92±0.05; BRL44408, 1.00±0.11; prazosin, 1.09±0.11; yohimbine, 1.12±0.08; WB4101, 0.97±0.09. The slopes were not significantly different from unity. Antagonist affinity estimates are means±s.e.m. for n animals in parentheses.

Noncompetitive antagonist parameter pD′2.

Apparent pKB.

Methods

Isolated tissues

Lungs and brains from pigs were obtained from the local slaughterhouse (Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Tierzucht und Tierhaltung, Teltow-Ruhlsdorf, Germany). During the transportation to the laboratory, lungs and brains were placed in ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit solution (KHS) of the following composition (in mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.5, MgSO4, 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, NaHCO3 25, and D -glucose 10 (pH 7.4). The solution was aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Small branches of intralobar pulmonary veins were dissected and placed in KHS. After removal of parenchyma and connective tissue, blood vessels were stored overnight at 4°C in previously gassed KHS. Preliminary experiments had shown that overnight storage of tissues did not impair the contractility of the smooth muscle. On the following day, the veins were cut into rings (3 mm long, 1.5 mm wide) which were horizontally suspended between two L-shaped stainless-steel hooks (150 μm diameter) and mounted in a water-jacketed 20 ml organ bath filled with KHS. The solution was continuously aerated with 95% O2/5% CO2 and warmed to a constant temperature of 37°C (pH 7.4). For continuous measurement of force changes, preparations were connected to an isometric force transducer (W Fleck, Mainz, Germany) attached to a TSE 4711 transducer coupler and a Siemens C1016 compensograph. Initial resting tension was adjusted to 10 mN at the beginning of each experiment.

Measurement of vascular tone

The venous rings were stabilized for 90 min with bath fluid replacement every 30 min. During a subsequent equilibration period of 180 min, vessels were stimulated first with 45 mM KCl and then four times with 0.3 μM of the α2-adrenoceptor agonist UK14304 with washings after each contractile challenge. This procedure was considered to yield stable and reproducible contractions. Tension was repeatedly readjusted to 10 mN and remained unchanged after the third UK14304 stimulation.

In a first set of experiments, we checked whether removal of the endothelium had an influence on cumulative concentration–response curves (CRCs) to UK14304. To rub off the endothelium, dental floss (Oral-B, Superfloss) was used by pulling it gently through the lumen of the blood vessel. The absence of endothelium was verified by the failure of carbachol (10 μM) to cause relaxation following the third contraction with UK14304. Cumulative CRCs to UK14304 were not different in the absence or presence of endothelium in porcine pulmonary veins (not shown). Therefore, no attempt was made to remove the endothelium in further experiments.

Agonists

To determine the contractile effects of agonists (noradrenaline, phenylephrine, clonidine and UK14304), a cumulative CRC to each agonist was constructed by increasing the agonist concentration cumulatively by half-log increments until a maximum response was observed. Cocaine (10 μM) and propranolol (1 μM) were present in the bath fluid to block neuronal uptake and β-adrenoceptors, respectively.

Antagonists

The participation of α2-adrenoceptors in the contractile response to UK14304 in porcine pulmonary veins was further assessed using a series of antagonists, which show relative selectivity for α2-adrenoceptors (ARC239, BRL44408, MK912, WB4101, prazosin, yohimbine and rauwolscine). Antagonists were generally added to the bath fluid 60 min before the construction of a cumulative CRC to UK14304. MK912 and rauwolscine (0.3 and 1 nM) were added 120 min before the construction of a CRC. UK14304 control curves showed no difference in Emax and pEC50 irrespective of an incubation time of 60 or 120 min. In this set of experiments, cocaine and propranolol were not present in the bath fluid, as both drugs had no influence on the CRCs to UK14304 (not shown).

RT-PCR

Small branches of porcine pulmonary veins were obtained as described above. To obtain a positive control of receptor expression in RT-PCR studies, pieces of cerebral cortex (cortex cerebri) of two pigs were isolated. Presence of mRNA in the central nervous system for the three subtypes of the α2-adrenoceptor has been reported in different animal species (Wikberg-Matsson et al., 1995; Saunders and Limbird, 1999). Veins and brain pieces were stored at −80°C. The frozen tissue was homogenized in guanidium thiocyanate solution using a Mikro-Dismembrator U (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) and the total RNA was extracted as described earlier (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 1987). Possible contaminating genomic DNA was removed by DNase treatment of the RNA sample. Subsequently, total RNA was purified using the GeneMATRIX Universal RNA Purification Kit (EURx Ltd, Gdañsk, Poland). RNA concentration was measured by UV absorbance at 260 nm using a GeneRay UV photometer (Biometra, Goettingen, Germany). Following denaturation of the RNA (2 μg) at 70°C, the first strand of cDNA was synthesized in a reaction volume of 25 μl reverse transcription buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3; 75 mM KCl; 3 mM MgCl2; 10 mM dithiothreitol) supplemented with 0.5 mM dNTPs, ribonuclease inhibitor (25 U) and M-MLV reverse transcriptase (200 U) (60 min, 37°C). To prove the absence of contamination with genomic DNA, a control was similarly prepared, except that the M-MLV reverse transcriptase was omitted (negative control). Two microlitres of the cDNA thus synthesized were diluted to a total volume of 50 μl containing the following components: Taq DNA Polymerase (1.25 U; EURx Ltd, Gdañsk, Poland), 200 μM of each dATP, dTTP, dGTP and dCTP, PCR buffer, 10 × AmpliBuffer B (1.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.01% Triton X-100; EURx Ltd., Gdańsk, Poland) and 1 μM of the following forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers (TiBMolBiol, Berlin, Germany): 5′-ATC ATT GCC GTG TTC ACA AGC and 5′-AAG AAG GAG CCG ATG CAA GAC for the pig α2A-adrenoceptor (GenBank entry NM214400, nucleotides 163–617); 5′-AAC TGG CCA CTG CTG GAG AG and 5′-TTC AGC CTC CTC CTC TGG TG for the pig α2B-adrenoceptor (NM 001037148, nucleotides 681–859); and 5′-CCA ACG AGC TCA TGG CCT AC and 5′-GAG ATG ACG GCC GAG ATG AG for the bovine α2C-adrenoceptor (AJ 488281, nucleotides 85–304). On the basis of the nucleotide sequence of porcine glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; AF 017079, nucleotides 513–895; positive control), the following primer pair (forward and reverse) was constructed (TiBMolBiol, Berlin, Germany): 5′-GTC AAG GCT GAG AAT GGG and 5′-GTC TTC TGG GTG GCA GTG ATG. To establish the appropriate primer pairs the following software was used: http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000). A control was included that contained all the components of the PCR except the template DNA. The PCR was performed in a Stratagene Robocycler Gradient 40 (Stratagene Europe, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) under the following conditions: cDNA was denaturated for 60 s at 95°C and annealed to the primers for 60 s at 55°C with the reaction extended for 90 s at 72°C and this procedure was repeated for 40 cycles. The amplified PCR products (fragment size of 455, 179, 220 and 383 bp for the α2A-, α2B-, α2C-adrenoceptor and GAPDH, respectively) were separated on 2% TAE-agarose gel, treated with ethidium bromide for 15 min, briefly differentiated with water and photographed.

Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR assays were carried out using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix on ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System according to the manufacturer's protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Amplification was performed in 10 μl reactions (Primer concentration 250 nM, 1 × SYBR Green Master Mix) containing 2 μl cDNA (equivalent to 10 ng of total RNA) in 40 cycles of 95°C, 15 s, 60°C, 1 min. Total RNA of three different sets of tissue was used to analyse receptor expression. Data normalization was performed using GAPDH as a reference gene. The following primer sequences were used for pig GAPDH (GenBank entry AF017079, nucleotides 156–399) (TiBMolBiol, Berlin, Germany): 5′-CAA ATT CCA CGG CAC AGT CA and 5′-CAT GCC CAT CAC AAA CAT GG. Relative mRNA expression was quantified using the comparative CT method according to the ABI manual. The following primer sequences were used (TiBMolBiol, Berlin, Germany): 5′-CGC TTG TCA TCC CTT TCT CG and 5′-CTC TAT GGC CTG GGT GAT GG for the pig α2A-adrenoceptor (NM 214400, nucleotides 251–420); 5′-AAC TGG CCA CTG CTG GAG AG and 5′-TTC AGC CTC CTC CTC TGG TG for the pig α2B-adrenoceptor (NM 001037148, nucleotides 681–859); and 5′-CCA ACG AGC TCA TGG CCT AC and 5′-GAG ATG ACG GCC GAG ATG AG for the bovine α2C-adrenoceptor (AJ 488281, nucleotides 85–304). Nucleotide sequences were retrieved and respective primer pairs constructed as mentioned above.

Data analysis and presentation

Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. for tissues from n animals. CRCs were fitted to the Hill equation using an iterative, least-squares method (GraphPad Prism 4.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) to provide estimates of the maximum response Emax (contractile response in % relative to the effect of the fourth UK14304 (0.3 μM)-induced contraction) and the half-maximum effective concentration pEC50 (the negative logarithm of the molar concentration of the agonist producing 50% of the maximal response). In these calculations, the bottom of the curves was fixed at 0 (i.e., 0% contraction over basal); the Hill slopes (nH) were kept variable.

Antagonist affinities were generally expressed as either an apparent pKB or a full pKB value. Apparent pKB values were calculated from the equation pKB=–log[B]+log(r−1), where [B] is the molar concentration of the antagonist and r the ratio of agonist EC50 measured in the presence and absence of antagonist (Furchgott, 1972). In the case of competitive antagonism (i.e., the antagonist produced parallel rightward shifts of the CRC without attenuation in the maximum response), antagonist affinities (full pKB) were estimated using the method of Arunlakshana and Schild (1959). If the Schild regression line had a slope not differing significantly from 1.00, the slope was constrained to unity. The intercept on the −log antagonist concentration axis provided the estimate of pKB (Jenkinson et al., 1995). For the noncompetitive antagonist MK912, a pD′2 value was calculated according to van Rossum (1963). pD′2 was defined as the negative logarithm of the molar concentration of antagonist which caused a 50% depression of the maximum response to the agonist: pD′2=−log[B]+log(Emax/Emax*−1), where Emax is the maximum response to the agonist in the absence of antagonist and Emax* the maximum response to the agonist in the presence of antagonist. Student's t-test (unpaired, two-tailed) was used to assess differences between two mean values with P<0.05 being considered as significant.

Drugs

The drugs used in the present study were obtained from the sources indicated: UK14304; gift from Allergan Pharmaceuticals, Westport, Co Mayo, Ireland; cocaine hydrochloride (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany); (R)-phenylephrine hydrochloride and yohimbine hydrochloride (Janssen, Beerse, Belgium); carbachol, clonidine hydrochloride, MK912, noradrenaline bitartrate, prazosin hydrochloride, (R,S)-propranolol hydrochloride and rauwolscine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany); ARC239, BRL44408 and WB4101 (Tocris, Bristol, UK).

All drugs were dissolved in distilled water to a 10 mM stock solution, except for prazosin, which was dissolved in 50% ethanol. Stock solutions were stored at –18°C and freshly diluted in distilled water before the beginning of the experiment. The final organ bath concentration of ethanol (which had no quantifiable effects) did not exceed 0.05%.

Results

Effects of agonists in porcine pulmonary veins

The purpose of these experiments was to study the contractile response to a series of agonists noradrenaline (pEC50=7.27±0.07, Emax=254±17%, n=8), UK14304 (pEC50=7.16±0.06, Emax=118±10%, n=4), clonidine (pEC50=7.04±0.08, Emax=50±7%, n=4) and phenylephrine (pEC50=5.92±0.07, Emax=150±10%, n=8) produced concentration-dependent contractile responses in porcine pulmonary veins (Figure 1). The Emax of noradrenaline was significantly higher when compared to that of the other compounds, whereas the Emax of UK14304 and phenylephrine did not significantly differ from each other. The ability of the selective α2-adrenoceptor agonists, UK14304 and clonidine, to contract porcine pulmonary veins indicates that this tissue is endowed with α2-adrenoceptors. As the selective α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine also contracted these blood vessels, α1-adrenoceptors may be present in this tissue.

Figure 1.

Cumulative log CRCs to α-adrenoceptor agonists in rings of porcine pulmonary veins. Values are mean±s.e.m. (vertical bars) from n animals as indicated in parentheses.

Effects of α2-adrenoceptor antagonists in porcine pulmonary veins

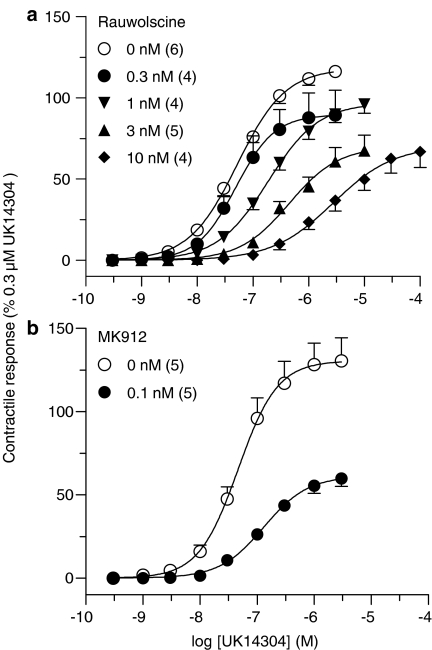

To determine the subtype(s) of α2-adrenoceptors mediating the contractile response in porcine pulmonary veins, we examined the effect of a series of relatively selective α2-adrenoceptor antagonists against UK14304. Antagonist effects of these drugs are summarized in Table 1. With the exception of MK912 and rauwolscine, all compounds caused a concentration-dependent rightward shift of the CRC to UK14304 with little or no effect on the maximum response. A four-point or five-point Schild regression for these data revealed competitive antagonism (Figure 2). The slopes of the Schild plots were not significantly different from unity (Table 1). In the case of rauwolscine, an apparent pKB value of 9.53 (Table 1) was determined from a single concentration of the drug (1 nM), as higher concentrations of rauwolscine led to insurmountable antagonism (i.e., depression of the maximum response and rightward shift of the UK14304 curve) (Figure 3a), precluding Schild regression analysis. MK912 (0.1 nM) slightly, but significantly, shifted the CRC to UK14304 to the right (log r=0.42±0.11, n=5) and induced a powerful depression of the maximum response (Figure 3b). Thus, MK912 fulfilled the criteria for non competitive antagonism and the noncompetitive antagonist parameter pD′2 was calculated, according to van Rossum (1963) (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Cumulative log CRCs to UK14304 in the absence or presence of ARC239 (a) BRL44408 (b) prazosin (c) WB4101 (d) and yohimbine (e) in rings of porcine pulmonary veins. The insets represent the Schild regression analysis of the respective CRCs. Values are means±s.e.m. (vertical bars) from n animals as indicated in parentheses.

Figure 3.

Cumulative log CRCs to UK14304 in the absence or presence of rauwolscine (a) and MK912 (b) in rings of porcine pulmonary veins. Values are means±s.e.m. (vertical bars) from n animals as indicated in parentheses.

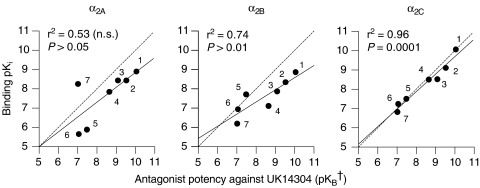

Attempts were made to correlate the affinity parameters determined in functional tests in pig pulmonary veins with their affinities (pKi values) at cloned human α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors (Uhlén et al., 1994). Affinities found in porcine pulmonary veins fitted best with radioligand binding data at the human α2C-adrenoceptor (Figure 4). Correlation with α2B-adrenoceptors was lower and no significant correlation was obtained with α2A-adrenoceptors (Figure 4). Re-calculation of the correlations excluding the affinities for rauwolscine and MK912, as both drugs failed to show competitive antagonism of the UK14304 response (see above), yielded a highly significant correlation for α2C-adrenoceptors (r2=0.94, P<0.01) and nonsignificant correlations for α2A-adrenoceptors (r2=0.32, P>0.30) and α2B-adrenoceptors (r2=0.40, P>0.25).

Figure 4.

Correlation of antagonist affinity estimates (pKB; †pD′2 in the case of MK912) against UK14304 at the contractile α2-adrenoceptor in porcine pulmonary veins and binding affinity (pKi) at human recombinant α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors. pKi values were taken from Uhlén et al. (1994). The dashed line represents the line of identity and the solid line, the regression line of the plotted points. The numbering of the drugs is as follows: MK912 (1), rauwolscine (2), yohimbine (3), WB4101 (4), ARC239 (5), prazosin (6) and BRL44408 (7).

RT-PCR and real-time PCR studies

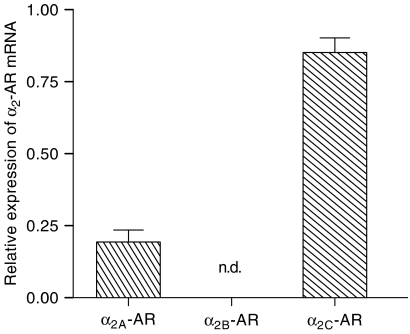

Using RT-PCR, we analysed the mRNAs for the three α2-adrenoceptor subtypes (α2A, α2B and α2C) expressed in porcine pulmonary veins. The amplification of GAPDH cDNA ensured the quality of the samples and the level of transcription. Control experiments of RT-PCR confirmed three different α2-adrenoceptor mRNAs, α2A, α2B and α2C in pig brain cortex. In porcine pulmonary veins only the expression of mRNA for α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors was detectable (Figure 5). Real-time PCR indicated that the relative mRNA amount of α2-adrenoceptor subtypes was α2C>>α2A. In agreement with the RT-PCR results, real-time analysis of PCR-products confirmed the absence of mRNA for the α2B-adrenoceptor in porcine pulmonary veins (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products showing the presence of mRNA for α2A-, α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors in pig cerebral cortex (upper panel) and the presence of mRNA for α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors in porcine pulmonary veins (lower panel). The marked lanes denote: 100 bp DNA ladder (M), positive control showing RT-PCR product of 383 bp using GAPDH primers (1), RT-PCR product of 455 bp obtained using forward and reverse primers of α2A-adrenoceptor (2), RT-PCR product of 179 bp obtained using forward and reverse primers of α2B-adrenoceptor (3), RT-PCR product of 220 bp obtained using forward and reverse primers of α2C-adrenoceptor (4), negative control, that is, a sample without reverse transcriptase to monitor genomic contamination (5) and negative control, that is, a PCR sample without template to monitor contamination of the reaction mixture (6). The size (bp) of three marker bands is indicated in the right margin.

Figure 6.

Real-time PCR results showing the relative expression of mRNA for α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors (AR) compared to GAPDH mRNA. Note that mRNA for the α2B-adrenoceptor was not detectable (n.d.), confirming the RT-PCR results. Values are means±s.e.m. (vertical bars) from three independent experiments.

Discussion

The primary objective of the present study was to examine the pharmacological characteristics of the postjunctional α2-adrenoceptor mediating contraction in porcine pulmonary veins. We could show that a number of adrenoceptor agonists, noradrenaline, phenylephrine, UK14304 and clonidine, elicited contractile responses in this tissue. Noradrenaline, a non-selective adrenoceptor agonist, exhibited a greater maximum response than the α1-adrenoceptor agonist phenylephrine and the α2-adrenoceptor agonists, UK14304 and clonidine, respectively; a finding that may be attributable to a simultaneous stimulation of both α1- and α2-adrenoceptors. In accordance with these findings, a mixed population of contractile α1- and α2-adrenoceptors has also been shown in canine pulmonary veins as well as in porcine palmar lateral vein and marginal ear vein (Ohlstein et al., 1989; Blaylock and Wilson, 1995; Wright et al., 1995).

It should be emphasized that agonist potencies alone did not allow definitive receptor identification and classification (Hoyer and Boddeke, 1993). Therefore, we used a number of antagonists to characterize the α2-adrenoceptor subtype(s) mediating the contractile response to UK14304 which exhibits selectivity for α2-adrenoceptors over α1-adrenoceptors (Cambridge, 1981). Although selective antagonists are now being developed to differentiate between the α2-adrenoceptor subtypes, there are, at present, no highly selective ligands available for the α2-adrenoceptor subtypes. Thus, pharmacological characterization is based on a limited range of compounds, which exhibit different affinities for the subtypes. The most valuable antagonists are: (i) BRL44408, with 30–120-fold selectivity for α2A-adrenoceptors versus α2B- and α2C-adrenoceptors; (ii) ARC239, with 40–70-fold selectivity for α2B/2C-adrenoceptors versus the α2A-adrenoceptor; and (iii) MK912 with 15-fold selectivity for α2C-adrenoceptor versus α2A- and α2B-adrenoceptors (Uhlén et al., 1994). Interestingly, ARC239 displayed a 52-fold higher antagonist affinity in pulmonary veins than in porcine ciliary arteries (Wikberg-Matsson and Simonsen, 2001). This argues against a role for α2A-adrenoceptors in UK14304-induced contraction in porcine pulmonary veins. Furthermore, the relatively low antagonist activity for BRL44408 (pKB 7.0), the high antagonist activities for MK912 (pD′2 10.1), ARC239 (pKB 7.5), WB4101 (pKB 8.7) and prazosin (pKB 7.1), and the absence of mRNA for the α2B-adrenoceptor (see below) argue for an α2C-adrenoceptor-mediated component of contraction in porcine pulmonary veins. This observation is supported by the correlation analysis between the affinity estimates for seven antagonists in porcine pulmonary veins and human binding data (Uhlén et al., 1994). Our study shows that antagonist potencies fitted best with binding affinity estimates (pKi) obtained for these antagonists at the human recombinant α2C-adrenoceptor. Correlation with α2B-adrenoceptors was less favourable, and no correlation was obtained with α2A-adrenoceptors. It is worth mentioning that, with the exception of rauwolscine and MK912, the rest of antagonists used behaved as competitive antagonists. Schild regression lines with slopes not significantly different from unity for ARC239, BRL44408, prazosin, yohimbine and WB4101 against UK14304 argue for a single receptor population (Kenakin, 1993) mediating the contractile response in porcine pulmonary veins. Rauwolscine induced a depression of the maximal UK14304 response, whereas MK912 behaved as a non competitive antagonist.

RT-PCR experiments using blood vessels with endothelium indicated an absence of mRNA for the α2B-adrenoceptor but the presence of mRNA for both α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors in porcine pulmonary veins. Quantitative measurement by real-time PCR showed a dominant expression of the mRNA for the α2C-adrenoceptor indicating a prominent role for the α2C-adrenoceptor in this vessel. The presence of mRNA for the α2A-adrenoceptor, showing a lower expression level than that for the α2C-adrenoceptor in real-time PCR, may result from the existence of prejunctional inhibitory α2A-adrenoceptors in the adventitia and/or relaxant α2A-adrenoceptors in the endothelium. The α2A-adrenoceptor has been shown to regulate neurotransmitter release from sympathetic neurons in almost all species and tissues (Trendelenburg et al., 1997). Moreover, the α2A-adrenoceptor mediates endothelium-dependent relaxation of porcine coronary arteries, although the endothelium of this vessel contains both α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors (Bockman et al., 1993). α2A-Adrenoceptors also appear to play the same functional role in the endothelium of other species (Guimarães and Moura, 2001). There is no reason to assume that neuronal α2-adrenoceptors (namely α2A-adrenoceptors) are involved in contractions in the present studies using porcine pulmonary venous rings. In addition, our functional studies clearly show that endothelial α2A-adrenoceptors are not involved in the contraction. The contractile smooth muscle α2-adrenoceptor in porcine pulmonary veins is of the α2C-type whereas the porcine endothelial relaxant α2-adrenoceptor is of the α2A-type. Porcine endothelial and smooth muscle cells are endowed with α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors, but functionally, both subtypes are linked to different and opposite vascular actions. Furthermore, our data show that the presence of α2A-adrenoceptor mRNA in a particular blood vessel cannot be taken as evidence that the receptor is necessarily involved in the contraction of that vessel (Piascik et al., 1995; Civantos Calzada and de Artiñano, 2001).

Contractile α2-adrenoceptors have recently been identified in porcine nasal veins (Corboz et al., 2007). α2A- and α2C-Adrenoceptor subtypes have been shown to be present in porcine nasal mucosa mediating contraction (Corboz et al., 2003). Using histological studies, it has also been demonstrated that the contraction in nasal mucosa was due to activation of veins in this tissue (Corboz et al., 2007). Thus, both subtypes, α2A- and α2C-adrenoceptors, are present in nasal mucosal veins and in pulmonary veins as well. However, in contrast to nasal mucosa veins from upper airway tissue, in veins from lower airway tissue, pulmonary veins in the present study, contraction is mediated solely by the α2C-adrenoceptor subtype.

In summary, the present data provide evidence that postjunctional α2C-adrenoceptors play a dominant role in mediating contraction to UK14304 in porcine pulmonary veins; functional and PCR studies rule out an involvement of α2A- and α2B-ARs. Moreover, a component of the contraction induced by noradrenaline or phenylephrine in these blood vessels may be mediated by α1-adrenoceptors, which should be characterized in further experiments which fall beyond the scope of the present study. As α2- adrenoceptor-mediated responsiveness is selectively enhanced under conditions of elevated pulmonary vascular tone (Hyman and Kadowitz, 1986; Shebuski et al., 1987), it would be of great interest to ascertain whether selective α2C-adrenoceptor antagonists are beneficial in the treatment of pulmonary venous hypertension and congestive heart failure.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported in part by a grant (no. 10021471) from IBB (Investitionsbank Berlin, Germany). The authors thank Allergan Pharmaceuticals (Ireland) for the gift of UK14304. We thank Dr Ingo Fritz (Roboklon GmbH, Berlin, Germany) for providing us with products from EURx Ltd (Gdañsk, Poland) and fruitful discussions. We also thank Dr Paulke and Mrs Uwarow of the Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Tierzucht und Tierhaltung (Teltow-Ruhlsdorf, Germany) for providing us with pig lungs for our studies.

Abbreviations

- ARC239

2-[2-(4-(2-methoxyphenyl)piperazin-1-yl)ethyl]-4,4-dimethyl-1,3-(2H,4H)-isoquinolindione dihydrochloride

- BRL44408

2-[(4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)methyl]-2,3-dihydro-1-methyl-1H-isoindole maleate

- CRC

concentration–response curve

- KHS

Krebs-Henseleit solution

- MK912

(2S-trans)-1,3,4,5′,6,6′,7,12b-octahydro-1′,3′-dimethyl-spiro[2H-benzofuro[2,3-a]quinolizine-2,4′(1′H)-pyrimidin]-2′(3′H)-one hydrochloride

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- UK14304

brimonidine tartrate

- WB4101

2-(2,6-dimethoxyphenoxyethyl)aminomethyl-1,4-benzodioxane hydrochloride

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Arunlakshana O, Schild HO. Some quantitative uses of drug antagonists. Br J Pharmacol. 1959;14:48–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1959.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaylock NA, Wilson VG. Pharmacological characterization of noradrenaline-induced contractions of the porcine isolated palmar lateral vein and palmar common digital artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:694–702. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb17194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockman CS, Jeffries WB, Abel PW. Binding and functional characterization of alpha-2 adrenergic receptor subtypes on pig vascular endothelium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;267:1126–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund DB, Eikenberg DC, Hieble JP, Langer SZ, Lefkowitz RJ, Minneman KP, et al. International Union of Pharmacology nomenclature of adrenoceptors. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:121–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund DB, Ray-Prenger C, Murphy TJ. Alpha-2A and alpha-2B adrenergic receptor subtypes: antagonist binding in tissues and cell lines containing only one subtype. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;245:600–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambridge D. UK-14, 304, a potent and selective α2-agonist for the characterisation of α-adrenoceptor subtypes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981;72:413–415. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90588-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civantos Calzada B, de Artiñano A. Alpha-adrenoceptor subtypes. Pharmacol Res. 2001;44:195–208. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corboz MR, Mutter JC, Rivelli MA, Mingo GG, McLeod RL, Varty L, et al. alpha2-adrenoceptor agonists as nasal decongestants. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corboz MR, Varty LM, Rizzo CA, Mutter JC, Rivelli MA, Wan Y, et al. Pharmacological characterization of α2-adrenoceptor-mediated responses in pig nasal mucosa. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2003;23:208–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty JR. Subtypes of functional α1- and α2-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;361:1–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furchgott RF.The classification of adrenoceptors (adrenergic receptors). An evaluation from the standpoint of receptor theory Catecholamines, Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology 1972Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, New York; 283–335.In: Blaschko H and Muscholl E (eds)Vol 33 [Google Scholar]

- Gavin KT, Colgan MP, Moore D, Shanik G, Docherty JR. α2C-Adrenoceptors mediate contractile responses to noradrenaline in the human saphenous vein. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;355:406–411. doi: 10.1007/pl00004961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães S, Moura D. Vascular adrenoceptors: an update. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:319–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer D, Boddeke HWGM. Partial agonists, full agonists, antagonists: dilemmas of definition. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:270–275. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman AL, Kadowitz PJ. Evidence for existence of postjunctional alpha-1 and alpha-2 adrenoceptors in cat pulmonary vascular bed. Am J Physiol. 1985;249:H891–H898. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.4.H891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman AL, Kadowitz PJ. Enhancement of α- and β-adrenoceptor responses by elevations in vascular tone in pulmonary circulation. Am J Physiol. 1986;250:H1109–H1116. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.250.6.H1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson DH, Barnard EA, Hoyer D, Humphrey PPA, Leff P, Shankley NP. International union of pharmacology committee on receptor nomenclature and drug classification: IX. Recommendations on terms and symbols in quantitative pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev. 1995;47:255–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Pharmacologic Analysis of Drug–Receptor-Interaction 1993Raven Press: New York; 2nd edn [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan SJ, Luong LA, Jasper JR, To ZP, Eglen RM. Characterization of α2-adrenoceptors mediating contraction of dog saphenous vein: identity with the human α2A subtype. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1721–1729. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlstein EH, Horohonich S, Shebuski RJ, Ruffolo RR., Jr Localization and characterization of alpha-2 adrenoceptors in the isolated canine pulmonary vein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;248:233–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva MQ, Morato M, Moura D, Guimarães S. A comparative study of postsynaptic α2-adrenoceptors of the dog mesenteric and rat femoral veins. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1999;360:165–170. doi: 10.1007/s002109900035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piascik MT, Guarino RD, Smith MS, Soltis EE, Saussy DL, Perez DM. The specific contribution of the novel alpha-1D adrenoceptor to the contraction of vascular smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1583–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt JL. Xenotransplantation. ASM Press: Washington, DC; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pound WJ, Houpt KA.The pig as a model in biomedical research The Biology of the Pig 1978Comstock Publishing Associates, Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY; 13–64.In: Pond WG (ed) [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S, Skaletsky HJ.Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers Bioinformatics Methods and Protocols: Methods in Molecular Biology 2000Humana Press: Totowa NJ; 365–386.In: Krawetz S and Misener S (eds)Source code available at [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders C, Limbird LE. Localization and trafficking of α2-adrenergic receptor subtypes in cells and tissues. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;84:193–205. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shebuski RJ, Ohlstein EH, Smith JM, Jr, Ruffolo RR., Jr Enhanced pulmonary alpha-2 adrenoceptor responsiveness under conditions of elevated pulmonary vascular tone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;242:158–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shebuski RJ, Fujita T, Ruffolo RR., Jr Evaluation of alpha-1 and alpha-2 adrenoceptor-mediated vasoconstriction in the in situ, autoperfused pulmonary circulation of the anaesthetized dog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;238:217–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trendelenburg AU, Sutej I, Wahl CA, Molderings GJ, Rump LC, Starke K. A re-investigation of questionable subclassifications of presynaptic alpha2-autoreceptors: rat vena cava, rat atria, human kidney and guinea-pig urethra. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;356:721–737. doi: 10.1007/pl00005111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlén S, Porter AC, Neubig RR. The novel alpha-2 adrenergic radioligand [3 H]-MK912 is alpha-2C selective among human alpha-2A, alpha-2B and alpha-2C adrenoceptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:1558–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlén S, Xia Y, Chhajlani V, Felder CC, Wikberg JE. [3H]-MK 912 binding delineates two α2-adrenoceptor subtypes in rat CNS one of which is identical with the cloned pA2d α2-adrenoceptor. Br J Pharmacol. 1992;106:986–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rossum JM. Cumulative dose-response curves. II. Technique for making dose-response curves in isolated organs and the evaluation of drug parameters. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1963;143:299–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikberg-Matsson A, Simonsen U. Potent α2A-adrenoceptor-mediated vasoconstriction by brimonidine in porcine ciliary arteries. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2049–2055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikberg-Matsson A, Wikberg JE, Uhlén S. Identification of drugs subtype-selective for α2A-, α2B-, and α2C-adrenoceptors in the pig cerebellum and kidney cortex. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;284:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00354-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems EW, Valdivia LF, Saxena PR, Villalón CM. The role of several α1- and α2-adrenoceptor subtypes mediating vasoconstriction in the canine external carotid circulation. Br J Pharmacol. 2001a;132:1292–1298. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems EW, Valdivia LF, Saxena PR, Villalón CM. Pharmacological profile of the mechanisms involved in the external carotid vascular effects of the antimigraine agent isometheptene in anaesthetised dogs. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2001b;364:27–32. doi: 10.1007/s002100100417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright IK, Blaylock NA, Kendall DA, Wilson VG. The relationship between density of alpha-adrenoceptor binding sites and contractile responses in several porcine isolated blood vessels. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:678–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb17192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young P, Berge J, Chapman H, Cawthorne MA. Novel α2-adrenoceptor antagonists show selectivity for α2A- and α2B-adrenoceptor subtypes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;168:381–386. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]