Abstract

Background and purpose:

Combining 5-HT1A receptor activation with dopamine D2/D3 receptor blockade should improve negative symptoms and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. We describe the in vitro profile of F15063 (N-[(2,2-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-benzofuran-7-yloxy)ethyl]-3-(cyclopent-1-enyl)-benzylamine).

Experimental approach:

F15063 was characterised in tests of binding affinity and in cellular models of signal transduction at monoamine receptors.

Key results:

Affinities (receptor and pK i values) of F15063 were: rD2 9.38; hD2L 9.44; hD2S 9.25; hD3 8.95; hD4 8.81; h5-HT1A 8.37. F15063 had little affinity (40-fold lower than D2) at other targets. F15063 antagonised dopamine-activated G-protein activation at hD2, rD2 and hD3 receptors with potency (pK b values 9.19, 8.29 and 8.74 in [35S]GTPγS binding experiments) similar to haloperidol. F15063 did not exhibit any hD2 receptor agonism, even in tests of ERK1/2 phosphorylation and G-protein activation in cells with high receptor expression. In contrast, like (±)8-OH-DPAT, F15063 efficaciously activated h5-HT1A (Emax 70%, pEC50 7.57) and r5-HT1A receptors (52%, 7.95) in tests of [35S]GTPγS binding, cAMP accumulation (90%, 7.12) and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (93%, 7.13). F15063 acted as a partial agonist for [35S]GTPγS binding at hD4 (29%, 8.15) and h5-HT1D receptors (35%, 7.68). In [35S]GTPγS autoradiography, F15063 activated G-proteins in hippocampus, cortex and septum (regions enriched in 5-HT1A receptors), but antagonised quinelorane-induced activation of D2/D3 receptors in striatum.

Conclusions and implications:

F15063 antagonised dopamine D2/D3 receptors, a property underlying its antipsychotic-like activity, whereas activation of 5-HT1A and D4 receptors mediated its actions in models of negative symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia (see companion papers).

Keywords: antipsychotic, dopamine D2, serotonin 5-HT1A, dopamine D4, G-protein, ERK1/2 phosphorylation, autoradiography

Introduction

The clinical treatment of schizophrenia is based on the use of antipsychotic agents, all of which interact at dopamine D2 receptors (Leysen, 2000). First-generation ‘conventional' antipsychotics like haloperidol are effective in controlling positive symptoms of schizophrenia, such as hallucinations, delusions and psychomotor agitation. However, they are essentially ineffective against negative symptoms, including social interaction deficits, disorganized speech and blunted affect. They also exhibit marked propensity for induction of a group of ‘Parkinson-like' neuromuscular disturbances known as the extrapyramidal syndrome (EPS). Further, these drugs do not alleviate a variety of cognitive symptoms, such as working and reference memory deficits, executive function impairments and decreased vigilance (Meltzer et al., 1999; Silver et al., 2003). More recent ‘atypical' antipsychotic agents, such as clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine and ziprasidone, interact at other receptors such as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) 5-HT2A/2C receptors, in addition to dopamine receptors. Thus, combined D2 and 5-HT2A/2C antagonism is associated with lowered EPS liability and improved capacity to alleviate (but not abolish) negative and cognitive symptoms (Davis et al., 2003; Leucht et al., 2003; Meltzer et al., 2003).

However, many schizophrenic patients fail to respond adequately to existing medications, and exhibit continuing impairments in both social functioning and cognitive performance, as well as persistent and/or recurrent psychotic episodes. These considerations, as well as difficulties associated with side-effect management (metabolic syndrome, cardiac impact) highlight the need for antipsychotic agents that display both wider therapeutic activity and improved safety profile. One approach to respond to this need has been to develop drugs possessing partial agonist properties at D2 receptors. The best characterized antipsychotic with this profile of activity is aripiprazole (Jordan et al., 2002; Shapiro et al., 2003), although other recent compounds, including bifeprunox and SSR181507, also display partial agonist properties (Bruins Slot et al., 2006; Cosi et al., 2006). By avoiding complete D2 receptor blockade, such a profile should lower the incidence of EPS whilst reducing dopamine release in brain regions associated with hyperdopaminergic activity in schizophrenia, such as nucleus accumbens. Another approach is to combine 5-HT1A agonist properties with D2 antagonism (Millan, 2000; Bantick et al., 2001). In fact, direct or indirect 5-HT1A receptor activation is implicated in the functional profiles of atypical antipsychotics, including clozapine, risperidone and aripiprazole (Cussac et al., 2002a; Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005 and see below) and a multiplicity of observations has highlighted 5-HT1A receptor activation as a means to respond to unmet needs in therapy of schizophrenia. Thus, 5-HT1A receptor activation reduces neuroleptic-induced catalepsy (Invernizzi et al., 1988; Prinssen et al., 2002), increases frontal cortex dopamine release (Rollema et al., 1997; Ichikawa and Meltzer, 2000; Assié et al., 2005; Diaz-Mataix et al., 2005), is beneficial in models of mood deficits and anxio-depressive states (Blier and Ward, 2003; Celada et al., 2004) and opposes dysfunctional glutamatergic transmission, consistent with activity against cognitive deficits induced by N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor hypofunction (Mauler et al., 2001; Czyrak et al., 2003; Auclair et al., 2006a; but see Wedzony et al., 2000).

It is important to note that clinical trials employing buspirone and tandospirone, drugs that act as 5-HT1A receptor partial agonists, have shown an attenuation of cognitive and negative deficits observed in neuroleptic-treated schizophrenic patients, and a reduction of the incidence of EPS (Sovner and Parnell-Sovner, 1989; Goff et al., 1991; Sumiyoshi et al., 2001a, 2001b). These observations support the notion that combining 5-HT1A receptor activation with D2 receptor blockade yields an improved ‘atypical' antipsychotic profile. However, the level of 5-HT1A receptor stimulation and the relative balance of 5-HT1A and D2 receptor interactions to obtain an optimal profile remain under discussion.

In view of the therapeutic potential of targeting 5-HT1A receptors, several recent antipsychotic agents have been selected to include varying degrees of agonist properties at these sites. In addition to clozapine, other antipsychotics, such as ziprasidone and nemonapride, as well as aripiprazole and bifeprunox exhibit partial agonist properties at 5-HT1A receptors, (Van Vliet et al., 2000; Cussac et al., 2002a; Jordan et al., 2002; Shapiro et al., 2003; Bruins Slot et al., 2006). Further, other drugs in various stages of development, such as SSR181507, SLV313 and the recently reported RGH-188, are specifically targeted at 5-HT1A receptors, in addition to dopamine receptors (McCreary et al., 2002; Glennon et al., 2002; Claustre et al., 2003; Depoortère et al., 2003; Kiss et al., 2006). Nevertheless, a series of comparative studies indicates that even modest alterations in the balance of 5-HT1A/D2 receptor activity profoundly influences the profile of action in preclinical models of antipsychotic-like activity (Assié et al., 2005; Bruins Slot et al., 2005; Kleven et al., 2005; Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005; Auclair et al., 2006b; Bardin et al., 2006a). Indeed, drugs that exhibit too pronounced a preference for 5-HT1A receptors, such as buspirone or the more recent anti-dyskinetic agent, sarizotan, fail to show activity in animal models of schizophrenic symptoms (Bardin et al., 2006a) and, correspondingly, are not clinically employed as antipsychotics. On the other hand, lower levels of 5-HT1A receptor activation by, for example, nemonapride and ziprasidone, result in residual catalepsy in rodents (Kleven et al., 2005; Bardin et al., 2006a). In addition, an appropriate level of 5-HT1A agonism is required for activity against PCP-induced social interaction deficit (Bruins Slot et al., 2005). These considerations illustrate the fundamental importance of identifying compounds that exhibit an optimal balance of D2/5-HT1A receptor properties in order to improve their therapeutic profile.

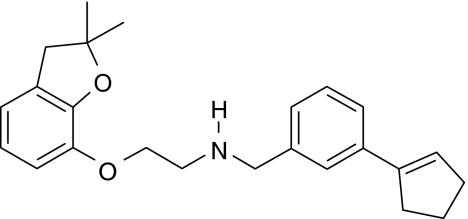

The present studies describe the in vitro pharmacological profile of a novel putative benzofurane antipsychotic, F15063 (N-[(2,2-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-benzofuran-7-yloxy)ethyl]-3-(cyclopent-1-enyl)-benzylamine), synthesized at the Centre de Recherche Pierre Fabre (Vacher et al., 2002). Its activity was investigated in a series of tests of affinity and signal transduction at monoamine receptors. F15063 exhibits an innovative profile of action, with potent anti-D2 dopaminergic and efficacious, but less potent, 5-HT1A receptor agonist properties. In addition, F15063 acts as a D4 receptor partial agonist, another property that distinguishes F15063 from established or potential new antipsychotic agents (Depoortère et al., 2006, 2007a, 2007b).

Methods

Competition-binding and signal transduction methods

Competition-binding and guanosine 5′-O-(gamma-thiotriphosphate) ([35S]GTPγS)-binding experiments were carried out using the radioligands, buffer and incubation conditions outlined in Tables 1 and 2. Experiments at native rat receptors employed brains of male Sprague–Dawley rats (Ico: OFA SD (SPF Caw); Iffa Credo, France), weighing 180–200 g. Rats were killed by decapitation and brains were rapidly dissected and stored at −70°C before use in binding assays. For native 5-HT2C receptor-binding assays (Pazos et al. 1985a, 1985b), pig cortex was obtained from the local slaughter house. All experimental procedures involving animals were in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive of 24 November 1986 (86/609/EEC) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, ML, USA), and were approved by the institutional Ethical Review Committee.

Table 1.

Summary of experimental conditions for determination of affinities at native brain monoamine binding sites in vitro

| Binding site | Brain tissue | [3H]Radioligand (nM) | Kd (nM) | Non-specific (μM) | Inc., buffer | Inc., time (min) & temp. (°C) | Literature reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rD2 | Rat striatum | Nemonapride (0.05) | 0.036 | (+)Butaclamol (1) | A | 60, 23° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (2005) |

| rD1 | Rat striatum | SCH 23390 (0.3) | 0.22 | SKF 38393 (10) | A | 30, 37° | Kleven et al. (1997) |

| r5-HT1A | Rat cortex | 8-OH-DPAT (0.2) | 3.1 | 5-HT (10) | B | 30, 23° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (2005) |

| r5-HT1A | Rat hippocampus | 8-OH-DPAT (0.2) | 0.49 | 5-HT (10) | C | 30, 23° | Kleven et al. (1997) |

| r5-HT1B | Rat cortex | GR125,743 (0.4) | 0.5 | 5-HT (10) | B | 30, 23° | Millan et al. (2002b) |

| r5-HT2A | Rat cortex | Ketanserin (0.2) | 3.1 | Methysergide (10) | B | 30, 23° | Kleven et al. (1997) |

| p5-HT2C | Pig cortex | Mesulergine (1) | 4.8 | Mianserin (10) | B | 60, 23° | Kleven et al. (1997) |

| rα1 | Rat cortex | Prazosin (0.1) | 0.063 | Phentolamine (50) | C | 30, 23° | Kleven et al. (1997) |

| rα2 | Rat cortex | RX 821002 (0.5) | 0.50 | Phentolamine (10) | C | 30, 23° | Hudson et al. (1992) |

| rSERT | Rat cortex | Citalopram (1) | 2.0 | Paroxetine (0.5) | A | 60, 23° | Assié and Koek (2000) |

Abbreviations: α1, α2: adrenoceptors; SERT=serotonin trasporter.

Buffers A: Tris-HCl 50 mM pH 7.4, NaCl 120 mM, KCl 5 mM. Buffer B: Tris-HCl 50 mM pH 7.4, pargyline 10 μM, CaCl2 4 mM, ascorbic acid 0.1%. Buffer C: Tris-HCl 50 mM pH 7.4.

Table 2.

Summary of experimental conditions for determination of affinities at recombinant human monoamine receptors in vitro

| Receptor | Cell line | [3H]Radioligand (nM) | Kd (nM) | Non-specific (μM) | Inc. buffer | Inc. time (min) & temp. (°C) | Literature reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hD2S | CHO | Spiperone (0.6) | 0.084 | (+)butaclamol (1) | A | 120, 37° | Cussac et al. (2000) |

| hD2L | CHO | Spiperone (0.6) | 0.035 | (+)butaclamol (1) | A | 120, 37° | Cussac et al. (2000) |

| hD3 | CHO | Spiperone (0.4) | 0.21 | Raclopride (10) | B | 160, 25° | Cussac et al. (2000) |

| hD4.4 | CHO | Spiperone (0.6) | 0.15 | Haloperidol (1) | A | 120, 37° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (1997) |

| hD1 | CHO | SCH23390 (0.1) | 0.38 | SKF38393 (10) | C | 120, 25° | Pedersen et al. (1994) |

| h5-HT1A | HeLa | 8-OH-DPAT (1) | 0.71 | 5-HT (10) | D | 30, 25° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (2005) |

| h5-HT1B | COS7 | 5-CT (3) | 0.65 | 5-HT (10) | D | 30, 25° | Pauwels et al. (1997) |

| h5-HT1D | COS7 | 5-CT (3) | 0.60 | 5-HT (10) | D | 30, 25° | Pauwels et al. (1997) |

| h5-HT2A | CHO | Ketanserin (0.5) | 0.24 | 5-HT (10) | A | 120, 23° | Millan et al. (2002a) |

| h5-HT2B | CHO | Mesulergine (2) | 1.68 | 5-HT (10) | A | 120, 23° | Millan et al. (2002a) |

| h5-HT2C | CHO | Mesulergine (2) | 0.56 | 5-HT (10) | A | 120, 23° | Millan et al. (2002a) |

| h5-HT7A | HEK293 | 5-CT (1.5) | 1.66 | 5-HT (10) | D | 90, 37° | Bard et al. (1993) |

| hα2A | C6 glial | RX821002 (2) | 1.16 | phentolamine (10) | E | 60, 25° | Wurch et al. (1999) |

| hα2B | C6 glial | RX821002 (10) | 9.27 | phentolamine (10) | E | 60, 25° | Wurch et al. (1999) |

| hα2C | C6 glial | RX821002 (4) | 2.21 | phentolamine (10) | E | 60, 25° | Wurch et al. (1999) |

Abbreviations: CHO, Chinese hamster ovary cells; HEK293, human embryonic kidney cells 293.

Buffer A: HEPES 20 mM (pH 7.4), NaCl 120 mM, KCl 5 mM, EDTA 1 mM, MgCl2 5 mM; Buffer B: Tris-HCl 50 mM (pH 7.6), NaCl 120 mM, KCl 5 mM; CaCl2 2 mM, MgCl2 5 mM, BSA 0.1%; Buffer C: HEPES 20 mM (pH 7.2); Buffer D: Tris-HCl 50 mM (pH 7.6), CaCl2 4 mM, pargyline 10 μM, ascorbic acid 0.1%; Buffer E: Tris-HCl 50 mM (pH 7.6).

Membranes from dissected brain tissues were prepared as previously described (see references in Table 1). The methodology used for rat hippocampal membranes typifies the approach: briefly, frozen brains were thawed, the hippocampi were dissected and homogenized in 20 volumes of ice-cold Tris-HCl 50 mM, pH 7.4 at 25°C. The homogenate was centrifuged at 39 000 g for 10 min, the pellet was resuspended in the same volume of buffer and was recentrifuged as before. Following a further resuspension, the tissue was incubated for 10 min at 37°C to favour dissociation of endogenous 5-HT and centrifuged again. The final pellet was suspended in the same buffer. The final tissue concentration was 3 mg/assay tube.

Binding experiments at recombinant human receptors were carried out using membranes from Chinese hamster ovary (CHO), human carcinoma (HeLa), C6 rat glial or human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cell lines stably expressing monoamine receptors. Alternatively, African green monkey kidney cells (COS7) or Spodoptera frugiperda (Sf9) insect cells transiently expressing the relevant receptors were used as described previously (see references in Tables 2 and 3). The methodology employed for HeLa-h5-HT1A (HA7 cells, Fargin et al., 1989) cells typifies the approach used for recombinant cell lines: briefly, HeLa-h5-HT1A cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum, gentamicin (100 μg/ml), and geneticin (G418) (400 μg/ml), in 5% CO2 at 37°C in a water-saturated atmosphere. The cells were plated in 150 cm2 Petri dishes until they reached a 90–100% confluence, after which they were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and stored at −80°C until used for [35S]GTPγS binding.

Table 3.

Summary of methods for determination of functional responses at native rat and recombinant human monoamine receptor in vitro

| Receptor | Tissue/cell line | Functional measure | Incubation conditions | Inc. time (min) & temp. (°C) | Literature reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rD2 | Rat striatum | [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer A | 60, 37° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (2001) |

| hD2L | Sf9 cells | [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer B | 40, 30° | Cosi et al. (2006) |

| hD2S | CHO cells | ERK1/2 phosphorylation | Ham's F12 serum-free | 5, 37° | Bruins Slot et al. (2006) |

| hD3 | COS cells | Gαo [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer C | 30, 30° | Pauwels et al. (2003) |

| hD4 | CHO cells | [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer D | 30, 23° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (1997) |

| r5-HT1A | Rat hippocampus | [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer A | 60, 37° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (2005) |

| r5-HT1A | Rat hippocampus | Gαo [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer E | 60, 23° | Martel et al. (2007) |

| h5-HT1A | HeLa cells | [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer F | 60, 30° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (2005) |

| h5-HT1A | HeLa cells | cAMP formation | Buffer G | 10, 23° | Newman-Tancredi et al. (2005) |

| h5-HT1A | CHO cells | ERK1/2 phosphorylation | RPMI serum-free | 5, 37° | Bruins Slot et al. (2006) |

| h5-HT1D | C6 glial cells | [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer C | 30, 23° | Pauwels et al. (1997) |

| h5-HT2A | CHO cells | Gαq [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer H | 60, 23° | Cussac et al. (2002b) |

| h5-HT2B | CHO cells | Gαq [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer H | 60, 23° | Cussac et al. (2002b) |

| h5-HT2C | CHO cells | Gαq [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer H | 60, 23° | Cussac et al. (2002b) |

| h5-HT7A | HEK293 cells | cAMP formation | Buffer I | 5, 37° | Rauly-Lestienne et al. (2004) |

| hα2A | C6 glial cells | [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer C | 30, 23° | Pauwels et al. (2003) |

| hα2C | C6 glial cells | [35S]GTPγS binding | Buffer C | 30, 23° | Pauwels et al. (2003) |

Abbreviations: CHO, Chinese hamster ovary cells; HeLa, human carcinoma cells; DTT, dithiothreitol.

Buffer A: 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 μM GDP, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM DTT; Buffer B: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 μM GDP, 0.1 mM DTT; Buffer C: 20mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 30 μM GDP; Buffer D: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 30 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 3 μM GDP; Buffer E: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 μM GDP, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM DTT; Buffer F: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 30 μM GDP, 10 μM pargyline; Buffer G: DMEM + 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 μM forskolin, 100 μM isobutylmethylxanthine; Buffer H: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1 μM GDP; Buffer I: 25 mM Tris-hCl, pH 7.4, 120 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose, 1 mM isobutylmethylxanthine.

When drugs were tested for antagonist properties, an additional 30 min pre-incubation was performed before addition of the agonist, except for ERK1/2 phosphorylation experiments (15 min pre-incubation).

G-protein activation experiments were carried out by [35S]GTPγS binding to cell membrane preparations. Other measures (cAMP formation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation) were carried out on whole cells.

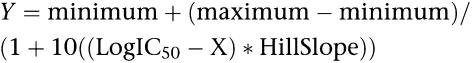

Experiments were carried out in duplicate or triplicate and repeated at least three times. All binding experiments terminated by rapid filtration, through Whatman GF-B fibre filters. Radioactivity retained on the filters was measured by liquid scintillation spectroscopy. Data from all experiments were analysed using non-linear curve fitting programs. Data from native tissue receptors were analysed using KELL RADLIG version 6 (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) and pKi values are given as mean±s.e.m. of at least three experiments, each comprising six to seven concentrations differing by one log unit interval. The Kd values of the different ligands are reported in Table 2. Data from human cloned receptor-binding experiments were analysed using GraphPad Prism, version 4 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), and pKi values are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of at least three experiments each comprising seven to 10 concentrations differing by 0.5 or 1 log unit interval. All data were analysed using a 4-parameter logistic equation:

|

where the maximum is defined by the values observed in the absence of competitor (100% value) and the minimum is defined in the presence of an excess of competing ligand (non-specific binding) respectively.

Functional responses at native rat and recombinant human receptors

The agonist/antagonist properties of F15063 at a range of rat and human receptors were determined in vitro for several measures of signal transduction representing different levels of intracellular responses: activation of G-proteins, inhibition of cyclic adenylyl cyclase accumulation and phosphorylation of extra-cellular signal regulated kinase (ERK1/2). An outline of methodologies, together with relevant literature references are shown in Table 3. In the case of recombinant human receptors, G-protein activation was monitored by [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes from CHO, HeLa, C6 glial and Sf9 insect cells.

Cyclic AMP accumulation was determined in HeLa-h5-HT1A cells as previously described (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005). Briefly, cells were incubated (10 min, room temperature) with compounds in DMEM, 10 mM HEPES, 100 μM forskolin, and 100 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX). The reaction was stopped by aspiration of the medium and addition of 0.1 N HCl. cAMP content was measured using a radioimmunoassay kit (Dupont NEN: NEK-033). Basal cAMP levels were 10±0.9 pmol/well (n=8). Emax values are expressed as % of the response obtained with 5-HT 10−5 M.

Extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 phosphorylation was examined using whole CHO-h5-HT1A or CHO-hD25 cells. Briefly, cells were grown until 90% confluent, washed once and starved overnight in serum-free medium. Cells were stimulated for 5 min with compounds diluted in serum-free medium. In antagonist studies, cells were incubated for 15 min with the relevant compound and then stimulated for 5 min with agonist. Reaction was stopped by lysis (15 min, room temperature) with RIPA buffer supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cell lysates were assayed for phospho-ERK (pERK) 1/2 content using an immunometric kit (Biosource, catalogue no. KHO0091, Camarillo, CA, USA), as described previously (Bruins Slot et al., 2006).

Isotherms were analysed by non-linear regression, using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and a four-parameter logistic equation (see above). The value of the minimum and maximum asymptotes was not fixed. The latter (Emax) is expressed as a percentage of the effect observed with a reference agonist, as indicated in Table 6. KB values of antagonists for inhibition of agonist action were calculated according to Lazareno and Birdsall (1993): KB=IC50: [1+(Agonist/EC50)], where IC50=inhibitory concentration50 of antagonist, agonist=concentration of agonist in the test and EC50=effective concentration50 of agonist.

Table 6.

Agonist and antagonist properties of F15063 at monoamine receptors determined by transduction assays in vitro

|

F15063 |

Reference ligand |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor | Efficacy model | Emax | pEC50 | pKb | Drug | Emax | pEC50 | pKb |

| rD2 | G-protein activation | 0 | 8.29±0.11 | Haloperidol | 0 | 8.45±0.07 | ||

| hD2L | G-protein activation | 0 | 9.19 (pA2) | Haloperidola | 0 | 9.12±0.10 | ||

| hD2S | ERK1/2 phosphorylation | 0 | 8.18±0.16 | Haloperidolb | 0 | 8.13±0.04 | ||

| hD3 | Gαo-protein activation | 0 | 8.74±0.04 | Haloperidol | 0 | 7.67±0.01 | ||

| hD4.4 | G-protein activation | 29±4 | 8.15±0.13 | 9.89±0.17 | Apomorphine | 42±4 | 7.99±0.06 | |

| r5-HT1A | G-protein activation | 36±4 | 7.47±0.11 | (±)8-OH-DPATc | 50±4 | 7.00±0.09 | ||

| r5-HT1A | Gαo-protein activation | 52±6 | 7.95±0.10 | (±)8-OH-DPAT | 63±6 | 7.27±0.12 | ||

| h5-HT1A | G-protein activation | 70±2 | 7.57±0.10 | (±)8-OH-DPATc | 82±4 | 7.59±0.04 | ||

| h5-HT1A | cAMP formation | 90±4 | 7.12±0.27 | (±)8-OH-DPATc | 82±5 | 7.65±0.25 | ||

| h5-HT1A | ERK1/2 phosphorylation | 93±8 | 7.13±0.14 | (±)8-OH-DPAT | 82±5 | 7.81±0.19 | ||

| h5-HT1D | G-protein activation | 35±2 | 7.68±0.02 | 8.02±0.12 | 5-HT | 99±2 | 8.36±0.06 | |

| h5-HT2A | Gαq-protein activation | 12±1 | 6.79±0.12 | 6.78±0.05 | MDL100907 | 0 | 9.36±0.12 | |

| h5-HT2B | Gαq-protein activation | 0 | 6.78±0.11 | RS127445 | 0 | 8.36±0.17 | ||

| h5-HT2C | Gαq-protein activation | 23±3d | 7.17±0.05 | SB242084 | 0 | 9.06±0.06 | ||

| h5-HT7A | cAMP formation | 0 | 6.22±0.05 | SB269970 | 0 | 7.79±0.17 | ||

| hα2A | G-protein activation | 0 | 6.90±0.06 | (±)RX821002 | 0 | 9.51±0.12 | ||

| hα2C | G-protein activation | 0 | 7.16±0.10 | (±)RX821002 | 0 | 8.89±0.01 | ||

Efficacy (Emax) values are expressed as % of the stimulation induced by saturating concentrations (10 μM) of 5-HT (for 5-HT receptors), dopamine (for dopamine receptors) or noradrenaline (for hα2A and hα2C receptors). Comparative data are shown for reference ligands.

Activation observed at 10 μM.

Functional autoradiography

[35S]Guanosine 5′-O-(gamma-thiotriphosphate ([35S]GTPγS) autoradiography was carried out essentially as described by Newman-Tancredi et al. (2003). Frozen rat brains were cut horizontally in 20 μm thick serial sections using a cryostat at −20°C, and fixed on microscope slides. Sections were kept frozen at −20°C until assayed. The assay was performed by pre-incubating the slides at room temperature for 15 min in buffer A (50 mM HEPES buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM EGTA and 0.2 mM dithiothreitol) plus 2.5 mM GTP, 15 min in buffer A plus 2.5 mM GDP, and 15 min in buffer A with 2.5 mM GDP, 10 mM MgCl2, and 100 mU/ml adenosine deaminase (=buffer B) plus antagonist. Sections were then incubated for 60 min at 37°C in buffer B containing 0.05 nM [35S]-GTPγS and drugs. Basal [35S]GTPγS binding was defined as that observed in the absence of drugs, and non-specific binding was defined as the binding in the presence of 100 μM unlabelled GTPγS. At the end of the incubation period, sections were rapidly washed twice for 2 min in cold buffer B (4°C), and rapidly dried under a flow of cold air. Dried sections, together with [14C]radioactivity standards were placed in X-ray cassettes, apposed to Biomax films and exposed for 4½ days. Films were developed and radioactivity on sections was quantified using an image analysis system (AIS system, InterFocus Ltd, Linton, UK). Grey levels were converted to nCi/g equivalents using [14C]radioactivity standards, and radioactivity was measured on each structures/sections. Sections were analysed in series of six adjacent sections, each having received a different treatments as described in Figure 7. Non-specific labelling for each structure was subtracted from the corresponding values determined under basal and ligand-treated conditions. The effect of ligand treatments on changes in radioactivity were expressed as percent change from specific basal values. Thus, 100% represents a doubling of labelling (Figure 8).

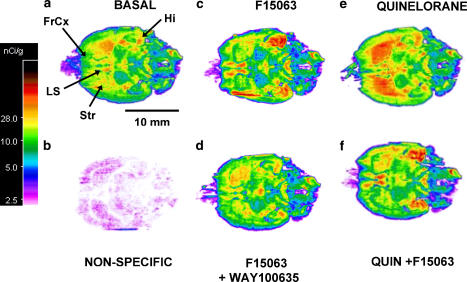

Figure 7.

F15063 exhibits dual 5-HT1A/D2 properties in functional autoradiography. Influence on G-protein activation in various regions of horizontal rat brain sections as determined by [35S]GTPγS autoradiography. (a) Basal conditions, that is no drugs; (b) non-specific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM unlabelled GTPγS; (c) F15063 (100 μM); (d) co-incubation of F15063 (100 μM) with the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY100 635 (10 μM). (e) Quinelorane (100 μM); (f) co-incubation of quinelorane (100 μM) with F15063 (100 μM). The lower end of spectrum (blue/pink) represents the lowest G-protein activation while the upper end of spectrum (red) represents the maximal response. Abbreviations: FrCx: frontal cortex; Hi: hippocampus; LS: lateral septum; Str: striatum.

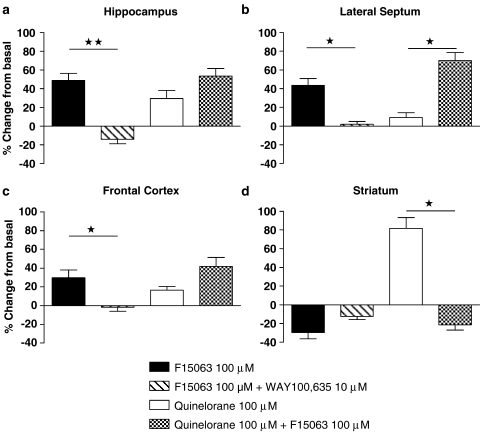

Figure 8.

F15063 increases 5-HT1A-mediated but blocks D2 receptor-mediated G-protein activation. Quantification of G-protein activation by F15063, as determined by [35S]GTPγS autoradiography, in (a) hippocampus, (b) lateral septum, (c) frontal cortex, (d) striatum. Bars represent the mean±s.e.m. values determined from quantification of autoradiograms of six animals. G-protein activation is expressed as percent changes from basal labelling. Statistical analyses were carried out by a Kruskall–Wallis test followed by Dunn's post hoc test. *P<0.05; **P<0.01.

Drugs

F15063 (N-[(2,2-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-benzofuran-7-yloxy)ethyl]-3-(cyclopent-1-enyl)-benzylamine mono-tartrate; Vacher et al., 2002; Cuisiat et al., in press) was synthesized by Medicinal Chemistry Division 1, Centre de Recherche Pierre Fabre (Castres, France). The following radioligands were purchased from Amersham Bioscience (manufacturer reference in brackets with specific activity): [3H]8-OH-DPAT (TRK.850: 5.92–8.88 TBq mmol−1), [3H]GR125,743 (TRK.1046: 1.85–3.18 TBq mmol−1), [3H]mesulergine (TRK.845: 2.59–3.15 TBq mmol−1), [3H]SCH 23390 (TRK.876: 2.22–3.33 TBq mmol−1), [3H]RX 821002 (TRK.914: 1.48–2.59 TBq mmol−1), [3H]citalopram (TRK.1068: 2.22–3.18 TBq mmol−1), [3H]prazosin (TRK.843: 2.41–3.15 TBq mmol−1), [3H]spiperone (TRK818: 2.89–3.44 TBq mmol−1), [35S]GTPγS (37–44 TBq mmol−1). The following radioligands were purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences (Courtaboeuf, France): [3H]ketanserin (NET-791: 2.22–3.33 TBq mmol−1), [3H]5-CT (NET-1071: 0.74–2.22 TBq mmol−1), and [3H]YM-09151–2 (i.e. [3H]nemonapride; NET-1004: 2.59–3.22 TBq mmol−1). Apomorphine HBr, dihydroergotamine mesylate, dopamine HCl, haloperidol, 5-HT creatinine sulphate, (±) 8-hydroxy-dipropylaminotryptamine ((±)8-OH-DPAT) bromohydrate, phentolamine mesylate, raclopride tartrate, methysergide maleate, mianserin HCl, SB269970 HCl, SKF38393 HCl and (+)butaclamol HCl were purchased from Sigma RBI (St Quentin Fallavier, France). GR127935 HCl, paroxetine, MDL100907, RS127445 HCl, RX821002 HCl, SB242084 HCl and sumatriptan HCl were synthesized by Jean-Louis Maurel, the Chemistry Dept., Centre de Recherche Pierre Fabre. Drugs were dissolved in distilled water or 10% DMSO at 10−3 M, and subsequent dilutions were prepared in the appropriate assay buffer (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of F15063.

Results

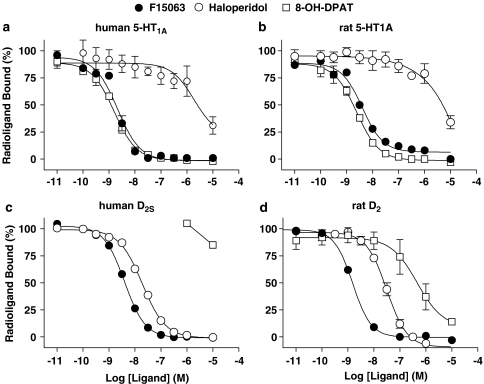

F15063 interacts at native brain and recombinant human D2 and 5-HT1A receptors

F15063 possessed high affinity at rat (r) brain D2 receptors and 14-fold lower affinity at r5-HT1A receptors (Table 4. Figure 2b and d). Correspondingly, F15063 exhibited high affinity at recombinant human (h) D2 and D3 receptors (pKi values >9) and about 10-fold lower affinity at hD4 and h5-HT1A receptors (Figure 2, Table 5). In comparison (data from Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005), haloperidol exhibited high affinity at rat striatal D2 receptors (pKi rD2=9.01; Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005). Using the protocol described in Table 2, haloperidol also exhibited high affinity at cloned human D2 receptors: pKi hD2L=8.96±0.03; pKi hD2S=8.56±0.02; but not at rat cortex or cloned human 5-HT1A receptors (pKi <6). In contrast, (±)8-OH-DPAT exhibited high affinity at rat cortex and cloned human 5-HT1A receptors (pKi=8.85 and 8.92; Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005). Using the protocols described in Table 1, (±)8-OH-DPAT also had high affinity at rat hippocampal 5-HT1A receptors (pKi=9.00±0.03), but not at rat striatal D2 receptors (pKi=6.26±0.03).

Table 4.

Affinities of F15063 at native brain monoamine sites

| Receptor | pKi±s.e.m. | Ki (95% CI) | Ki ratio vs rD2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| rD2 | 9.38±0.05 | 0.42 (0.26–0.66) | 1 |

| rD1 | 5.89±0.03 | 1284 (950–1738) | 3057 |

| r5-HT1A (cortex) | 8.24±0.07 | 5.9 (3.0–11.2) | 14 |

| r5-HT1A (hippocampus) | 8.65±0.09 | 2.3 (1.0–5.3) | 5 |

| r5-HT1B | 6.31±0.10 | 487 (180–1315) | 1159 |

| r5-HT2A | 6.57±0.01 | 270 (237–306) | 643 |

| p5-HT2C | 6.50±0.17 | 318 (57–1781) | 757 |

| rα1 | 7.29±0.01 | 51 (46–56) | 121 |

| rα2 | 6.52±0.02 | 303 (255–360) | 721 |

| rSERT | 5.98±0.03 | 1045 (776–1406) | 2488 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Affinity values were calculated from competition binding experiments and derived pKi values are shown±s.e.m. The corresponding geometric mean of Ki values (in nanomolar) are shown with their 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 2.

F15063 inhibits radioligand binding at 5-HT1A and D2 receptors. Competition-binding curves for F15063 in comparison with haloperidol and (±)8-OH-DPAT at: (a) human 5-HT1A receptors expressed in HeLa cells; (b) rat hippocampal 5-HT1A receptors; (c) human D2S receptors expressed in CHO cells; (d) rat striatal D2 receptors. Binding conditions are described in Tables 1 and 2 and values are mean±s.e.m. from three experiments performed in triplicate or in duplicate. Data from these experiments are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 5.

Affinities of F15063 at recombinant human monoamine receptors

| Receptor | pKi±s.e.m. | Ki (95% CI) | Ki ratio vs rD2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| hD2L | 9.44±0.01 | 0.36 (0.32–0.42) | 1 |

| hD2S | 9.25±0.01 | 0.56 (0.55–0.58) | 1.6 |

| hD3 | 8.95±0.05 | 1.12 (0.68–1.58) | 3.1 |

| hD4.4 | 8.81±0.08 | 1.53 (0.68–3.48) | 4.3 |

| hD1 | 6.51±0.16 | 312 (67–1454) | 867 |

| h5-HT1A | 8.37±0.02 | 4.23 (3.36–5.34) | 12 |

| h5-HT1B | 7.04±0.05 | 91 (56–145) | 253 |

| h5-HT1D | 7.89±0.05 | 13 (7.5–21) | 36 |

| h5-HT2A | 7.77±0.08 | 17 (7–38) | 47 |

| h5-HT2B | 7.71±0.05 | 19 (12–32) | 53 |

| h5-HT2C | 7.27±0.08 | 53 (24–118) | 147 |

| h5-HT7A | 6.60±0.08 | 237 (140–400) | 658 |

| hα2A | 6.81±0.02 | 156 (136–179) | 433 |

| hα2B | 7.02±0.04 | 96 (65–141) | 266 |

| hα2C | 7.20±0.06 | 60 (33–108) | 166 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

Affinity values were calculated from competition binding experiments and derived pKi values are shown±s.e.m. The corresponding geometric mean of Ki values (in nanomolar) are shown with their 95% confidence intervals.

F15063 interacted much more weakly (>30-fold less affinity than for D2 receptors; see Tables 4 and 5) with a range of other targets. Thus, F15063 exhibited low or negligible affinity for D1 receptors, as well as only modest affinity at α1 and α2 adrenoceptors both in rat tissue and in cloned systems (Tables 4 and 5). The affinity of F15063 for native rat 5-HT2A/2C receptors was low, relative to its affinity at D2 receptors. F15063 also had only modest affinity at h5-HT2A/2B/2C receptors (at least 47-fold lower than that at hD2L receptors). F15063 exhibited modest affinity at h5-HT1D receptors (36-fold less than at hD2L receptors, Table 5) but very little at human or rat 5-HT1B. F15063 interacted weakly with serotonin transporters in rat cortex.

In a receptor screen carried out on F15063 by Cerep (Courtaboeuf, France; data on file), weak interactions were detected with sigma sites (pKi=7.0), rat cerebral cortex verapamil site Ca2+ (6.68), site-2 Na+ channels (6.54), histamine H2 (6.49) and dopamine hD5 receptors (6.16). In addition, F15063 did not interact (less than 50% inhibition of radioligand binding at 1 μM) with a series of other sites, including 5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT6, muscarinic (M1, M2, M3, M4 and M5), histaminergic (H1 and H3), adenosine (A1, A2A), β1 adrenoceptors, opiate, benzodiazepine, GABA-A, GABA-B, AMPA, kainate, PCP and NMDA receptors, dopamine or noradrenaline transporters, ATP-sensitive, voltage-sensitive or Ca2+-dependent K+ channels, diltiazem site or DHP site Ca2+ channels or site-1 Na+ channels. F15063 did not inhibit acetylcholinesterase, MAO-A or MAO-B enzyme activities.

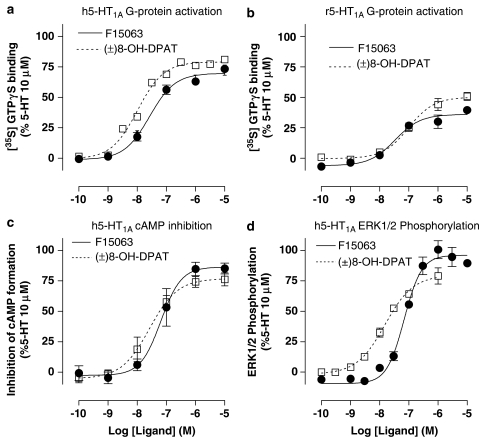

F15063 activates native rat and recombinant human 5-HT1A receptors

In G-protein activation measures, determined by binding of [35S]GTPγS to HeLa cell membranes expressing recombinant h5-HT1A receptors, F15063 markedly increased G-protein activation with a maximal response of 70% relative to that induced by 5-HT and of a similar magnitude to that exhibited by (±)8-OH-DPAT (82%, Table 6; Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

F15063 efficaciously activates cloned human and native rat 5-HT1A receptors. (a) Stimulation by F15063 of G-protein activation determined using [35S]GTPγS binding at recombinant human (HeLa-h5-HT1A) and (b) native rat hippocampal 5-HT1A receptors. (c) Inhibition of cAMP accumulation in HeLa-h5-HT1A cells. (d) stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation at h5-HT1A receptors expressed in CHO cells. Data are expressed as percentage of the effect induced by a saturating concentration of 5-HT (10 μM). Values are mean±s.e.m. from three experiments performed in triplicate or in duplicate. For comparison, the dotted line represents results obtained under the same conditions for (±)8-OH-DPAT (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005; Bruins Slot et al., 2006). Data from these experiments are shown in Table 6.

In the same cell line, F15063 also inhibited cyclic AMP formation, demonstrating an influence on second messenger signal transduction in living cells. The maximal response to F15063 was 90% of that observed with 5-HT, similar to that observed with (±)8-OH-DPAT (Figure 3).

In CHO cells stably expressing h5-HT1A receptors, F15063 concentration-dependently stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2, a down-stream response to 5-HT1A receptor activation. The maximal efficacy was 93% relative to that of 5-HT and was slightly greater than that observed with (±)8-OH-DPAT in this system (Table 6).

F15063 also stimulated total G-protein activation in rat hippocampal membranes, indicating that it activates native 5-HT1A receptors in a brain region relevant to potential therapeutic properties (Table 6, Figure 3). The maximal stimulation in this system was 36% relative to that of 5-HT. The influence of F15063 in hippocampal membranes was entirely mediated by 5-HT1A receptors, as demonstrated by its complete blockade with the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY100 635. The latter abolished F15063 (1 μM)-stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding with a pIC50 of 7.23±0.08 and a pKb of 8.71±0.08 (n=3).

In a G-protein subtype targeting procedure ([35S]GTPγS binding coupled to antibody-capture and SPA detection), F15063 stimulated Gαo activation in rat hippocampal membranes by 52% relative to 5-HT, similar to (±)8-OH-DPAT (Table 6).

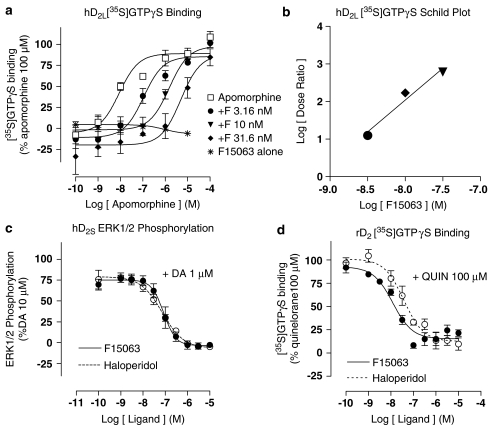

F15063 antagonizes native rat and recombinant human D2 receptors

In Sf9 cells expressing recombinant human D2L (long isoform) receptors, F15063 did not induce any increase in [35S]GTPγS labelling to endogenous G-proteins, consistent with absence of agonist properties for G-protein activation at this site (Table 6, Figure 4). In contrast, the reference agonist, apomorphine, induced a potent stimulation of G-protein activation. The apomorphine stimulation curve was progressively shifted to the right by the addition of increasing concentrations of F15063, consistent with competitive antagonist actions at hD2 receptors (Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

F15063 antagonizes cloned human and native rat D2 receptors. (a) F15063 induces a rightward shift of a concentration-effect curve of apomorphine-induced stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes of Sf9 cells expressing recombinant hD2L receptors. Points are mean±s.e.m. of values from three experiments performed in triplicate. (b) Schild plot of the data from (a). (c) F15063 reverses the stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by dopamine in CHO cells expressing recombinant hD2S receptors. (d) F15063 antagonizes quinelorane-induced [35S]GTPγS binding to rat striatal membranes. Points are mean±s.e.m. of values from three experiments performed in triplicate. For comparative purposes, the dotted line represents the results obtained for haloperidol under the same conditions. Data from these experiments are shown in Table 6.

The EC50 value of apomorphine alone was 8.7±1.1 nM; EC50 value in the presence of 3.16 nM F15063: 116±26 nM; with 10 nM F15063: 1500±55 nM; with 31.6 nM F15063: 5516±995 nM. The pA2 value derived from the Schild plot of these data (Figure 4b) was pA2=9.19 with a slope of 1.71. The antagonist potency of haloperidol was similar (Table 6).

In CHO cells stably expressing hD2S (short isoform) receptors, F15063 did not induce any ERK1/2 phosphorylation when tested alone, but potently antagonized ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by dopamine, indicating that F15063 behaves as a potent antagonist at dopamine D2 receptors (Figure 4c; Table 6). Haloperidol likewise blocked ERK1/2 phosphorylation without inducing any by itself.

In rat striatal membranes F15063 did not stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding, but abolished the stimulation induced by the dopaminergic agonist, quinelorane, demonstrating antagonist properties at native rat D2 receptors (Figure 4d). The antagonist potency of F15063 at rD2 dopamine receptors was similar to that of haloperidol (Table 6).

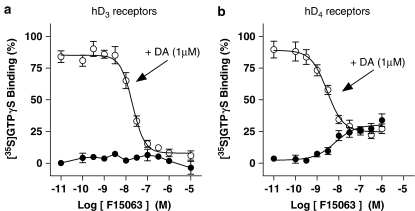

F15063 antagonizes hD3, but has partial agonist properties at hD4 receptors

When tested alone, F15063 did not modify activation of Gαo G-proteins transiently co-expressed with hD3 receptors in Cos7 cells, consistent with an absence of agonist properties (Figure 5a). In contrast, F15063 antagonized dopamine-induced [35S]GTPγS binding to Gαo proteins (Table 6), consistent with potent antagonist properties at D3 receptors.

Figure 5.

F15063 antagonizes hD3 but shows partial agonism at hD4 receptors. (a) Blockade by F15063 of dopamine-stimulated hD3 receptor-mediated Gαo protein activation. Cos7 cells were co-transfected with hD3 receptors and Gαo (C351I) subunits. Gαo-protein activation was determined by [35S]GTPγS binding. (b) Stimulation by F15063 of hD4 receptor-mediated G-protein activation in stably transfected CHO cells. Values are mean±s.e.m. from at least three experiments performed in triplicate or in duplicate of F15063 tested alone (filled circles) and in the presence of 1 μM dopamine (empty circles). Data from these experiments are shown in Table 6.

In membranes of CHO cells expressing hD4 (4-repeat isoform) receptors, F15063 moderately increased G-protein activation (∼30% relative to that of the full agonist, dopamine), as measured in [35S]GTPγS-binding experiments. In the presence of dopamine, F15063 potently reduced dopamine-induced [35S]GTPγS binding to the same level as that seen with F15063 alone (Figure 5b). These data demonstrate partial agonist properties of F15063 at dopamine D4 receptors (Table 6). Under the same conditions, apomorphine yielded an Emax value of 42%.

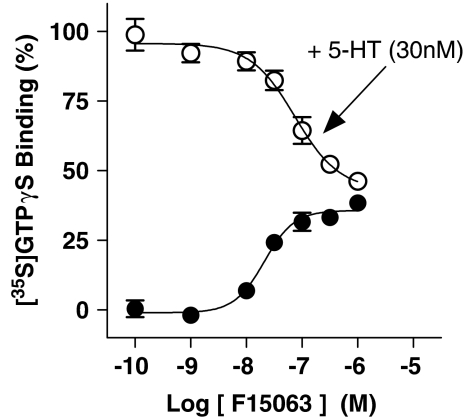

F15063 has modest or weak actions at other receptor subtypes

In contrast to its potent actions at D2-like and 5-HT1A receptors (responses in the nanomolar range), F15063 elicited modest or weak actions at other receptors. At h5-HT1D receptors expressed in C6 glioma cells, F15063 induced a modest stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding, but reduced the stimulation induced by 5-HT (Table 6, Figure 6). These data demonstrate partial agonism of F15063 at h5-HT1D receptors. For comparative purposes, three additional compounds were tested in the same system: the antimigraine agents, dihydroergotamine (Emax 75±2%, pEC50 9.13±0.07, n=3) and sumatriptan (87±3%, 7.75±0.09, n=8), and the weak partial agonist, GR127935 (50±4%, 8.07±0.07, n=3).

Figure 6.

F15063 shows partial agonism at h5-HT1D receptors. Stimulation by F15063 of h5-HT1D receptor-mediated G-protein activation in stably transfected C6-glial cells. Values are mean±s.e.m. from at least three experiments performed in triplicate or in duplicate of F15063 tested alone (filled circles) and in the presence of 30 nM 5-HT (empty circles). Data from these experiments are shown in Table 6.

F15063 acted as a low-potency antagonist (pKb∼7) at h5-HT2A/2B/2C receptors in a model of Gαq protein activation (Table 6), although a very slight increase in Gαq activation was detected at high concentrations at h5-HT2A and h5-HT2C receptors (Table 6). At micromolar concentrations, F15063 also blocked noradrenaline-induced G-protein activation of hα2A and hα2C receptors (Table 6). At h5-HT7 receptors, F15063 had no influence on cyclic AMP formation when tested alone, but reversed the stimulation of cAMP formation induced by 5-HT, indicating low-potency neutral antagonist properties at h5-HT7 receptors (Table 6).

F15063 exhibits dual 5-HT1A/D2 properties in functional autoradiography

Incubation of rat brain horizontal sections with a 100 μM of F15063 induced an increase in [35S]GTPγS binding in brain areas rich in 5-HT1A receptors, including hippocampus, lateral septum and limbic cortex (Figure 7). This effect of F15063 was abolished by co-incubation of F15063 with WAY100 635 (10 μM), confirming that the stimulation is specifically mediated by 5-HT1A receptor activation. F15063 did not stimulate labelling of brain regions such as striatum, that are rich in D2 receptors, indicating absence of agonist properties at native D2 receptors under these conditions (Figure 7). F15063 even tended to reduce labelling of striatum below basal values, suggestive of potential inverse agonism at high concentrations (see quantification of autoradiograms by densitometry, Figure 8). In comparison, [35S]GTPγS labelling of striatum was strongly increased by incubation of sections with the dopaminergic agonist, quinelorane (100 μM). F15063 abolished quinelorane-induced binding in striatum, indicating antagonist actions (Figure 8). When sections are incubated with both quinelorane and F15063, the increase in [35S]GTPγS binding in brain structures responding to 5-HT1A activation by F15063 can be observed (Figure 7).

Discussion

Balance of affinity of F15063 at dopamine D2-like and 5-HT1A receptors in vitro

F15063 is a member of a new generation of antipsychotic agents that combine dopamine D2 receptor blockade and activation of 5-HT1A receptors. Ample evidence indicates that such a profile should result in a favourable ‘atypical' antipsychotic profile, but the balance of 5-HT1A and D2 interactions can profoundly influence the in vivo actions of such drugs (see Introduction and Assié et al., 2005; Bruins Slot et al. 2005; Kleven et al. 2005; Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005; Auclair et al., 2006b; Bardin et al., 2006a). Thus, antipsychotics that lack 5-HT1A receptor activation, as in the case of haloperidol, are associated with EPS induction and lack of beneficial influence against negative symptoms. On the other hand, excessive 5-HT1A receptor activation negates the dopamine D2 antagonism necessary for antipsychotic action and disrupts pre-pulse inhibition, a model of sensorymotor gating (Auclair et al., 2006a; Bardin et al., 2006a). In the case of F15063, the balance of dopamine D2 receptor blockade and 5-HT1A receptor agonism results in a favourable profile of pharmacological activities with potent actions in vivo in models of positive symptoms, negative symptoms and cognitive deficits (Depoortère et al., 2007a, 2007b). F15063 possesses high affinity at both native rat and cloned human D2 receptors, (pKi value>9) and 10–20-fold lower affinity at rat/human 5-HT1A receptors (Tables 4 and 5). The affinity of F15063 at D2 receptors is comparable to that of other potent antipsychotics at this receptor, such as haloperidol or risperidone (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005). In comparison, the affinity of F15063 at 5-HT1A receptors is similar to that of the prototypic 5-HT1A receptor agonist, (±)8-OH-DPAT. The ratio of affinity at these receptors is an important consideration in the profile of activity of the compound. Indeed, other ‘new generation' drugs, such as SSR181507 and SLV313 (currently undergoing clinical evaluation), have higher affinity at 5-HT1A relative to D2 receptors whereas bifeprunox has a reversed balance of affinity (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005). Although clinical data relating to 5-HT1A/D2 properties are as yet unavailable for these drugs, it may be speculated that these compounds do not fall within an ‘optimal activity window' of 5-HT1A/D2 balance, because they are not as active in a variety of in vivo behavioural models of social withdrawal (Bruins Slot et al., 2005), dopamine release in frontal cortex (Assié et al., 2005) or cognitive deficits (Auclair et al., 2006a; Bardin et al., 2006b).

F15063 activates 5-HT1A receptors and antagonizes D2 receptors

Relative affinities at D2 and 5-HT1A receptors must be interpreted in the context of the agonist/antagonist properties at these sites. In the case of F15063, potent antagonism at D2 receptors is demonstrated in vitro in rat striatal membranes, where it reversed quinelorane-induced G-protein activation. F15063 also behaved as a neutral antagonist in downstream transduction systems that are sensitive to weak partial agonist properties, such as activation of G-proteins at hD2 receptors in a high-expressing Sf9 cell system (Cosi et al., 2006). In contrast, SSR181507, aripiprazole and bifeprunox behaved as D2 partial agonists in this system. F15063 also behaved as a ‘silent' antagonist for stimulation of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in CHO cells whereas aripiprazole, bifeprunox and SSR181507 acted as partial agonists (Bruins Slot et al., 2006). The latter observation is particularly interesting in view of the involvement of this pathway in the antipsychotic-like actions of clozapine in vivo (Browning et al., 2005). The potent D2 receptor antagonist properties of F15063 are of the same order of magnitude as those of haloperidol (Figure 4) and manifest themselves in vivo in models of hyperdopaminergic activity induced by methylphenidate or amphetamine in rats, or by apomorphine, in mice (Depoortère et al., 2007b). Thus, the activity of F15063 contrasts with that of other antipsychotics targeting D2 and 5-HT1A receptors, such as bifeprunox, SSR181507 and aripiprazole, (although the latter has multiple additional interactions). These three drugs all act as partial agonists at D2 receptors, a property that is associated with reduced liability to induce EPS and hyperprolactinaemia (Cosi et al., 2006). However, D2 partial agonists, such as aripiprazole and bifeprunox, are also somewhat less potent in models of positive symptoms of schizophrenia and have less influence on frontal cortex dopamine release (Li et al., 2004; Assié et al., 2005; Bardin et al., 2006a) and recent data show that aripiprazole fails to reverse PCP-induced deficits in reversal learning, whereas F15063 does (Auclair et al., 2006a; Depoortère et al., 2006, 2007b). Further, D2 receptor partial agonist activity, in combination with 5-HT1A receptor activation, disrupts basal pre-pulse inhibition in rats, suggesting that such drugs may interfere with sensorimotor gating response (Auclair et al., 2006b). Hence, the relative benefits of partial agonist properties at D2 receptors in antipsychotic therapy remain under discussion and F15063 provides, with SLV313 (also a pure D2 receptor antagonist; Bruins Slot et al., 2006; Cosi et al., 2006), a different balance of efficacy at D2 versus 5-HT1A receptors compared with that of other new generation antipsychotics. An earlier antipsychotic, ziprasidone, also displays 5-HT1A receptor partial agonism but is also potently active at other sites, including 5-HT2A receptors (Leysen, 2000). Its balance of receptor activity appears less favourable than that of F15063, as indicated by the propensity of ziprasidone to dose-dependently induce catalepsy in rats and mice (Kleven et al., 2005; Bardin et al., 2006a) and its failure to reverse PCP-induced social interaction deficits in rats (Bruins Slot et al., 2005).

As concerns 5-HT1A receptors, F15063 consistently exhibited marked efficacy at 5-HT1A receptors, similar to that of the prototypical agonist, (±)8-OH-DPAT, and greater than that of other antipsychotics, including clozapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole as well as SLV313 (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005; Bruins Slot et al., 2006; Table 6). Thus, F15063 efficaciously stimulated 5-HT1A receptor signalling at different levels of signal transduction: G-protein activation, cyclic AMP accumulation and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. It is notable that, in the latter two systems, downstream of G-protein activation, the efficacy of F15063 relative to that of 5-HT was amplified, consistent with substantial agonist properties (Figure 3). In comparison, F15063 also exhibited agonist activity at rat brain 5-HT1A receptors in tests of total and Gαo-specific G-protein activation in rat hippocampal membranes. In these experiments the Emax values of F15063 were lower than those observed in cell lines, an observation attributable to two factors: first, receptor expression levels are lower in hippocampus than in recombinant cell lines, and, second, hippocampal membranes express a multiplicity of serotonin receptors: about 85% of the 5-HT-mediated effect is due to 5-HT1A receptors, the rest is due to activation of other sites (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005). In contrast, the totality of the influence of F15063 in hippocampal membranes is mediated by 5-HT1A receptors, as was demonstrated by its complete blockade with the selective 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY100 635.

The dual D2 antagonist and 5-HT1A agonist properties of F15063 result in a complementary pattern of receptor activation in brain regions expressing these sites. Thus, in functional autoradiography experiments, and consistent with other studies using this methodology (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2001, 2003), F15063 stimulated 5-HT1A receptor-coupled G-protein activation in the hippocampus, septum and frontal cortex, structures with substantial expression levels of 5-HT1A receptors. In contrast, F15063 did not stimulate G-protein activation in striatum but blocked quinelorane-induced activation in this brain region that expresses high levels of D2 receptors. Although these data demonstrate the dual D2/5-HT1A properties of F15063, further studies need to address the issue of concentration–response relationships for these effects. Indeed, it is likely that the concentrations of F15063 producing 5-HT1A/D2 responses in various brain regions will differ from those of other recent antipsychotics, such as ziprasidone and aripiprazole, that have weaker partial agonist actions at 5-HT1A receptors (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005; Bruins Slot et al., 2006). In contrast, some new drugs in development, such as SSR181507 and SLV313, have higher potency and/or efficacy at 5-HT1A receptors but display marked diversity in their behavioural and neurochemical profiles (see Introduction), illustrating the profound influence that modifications in D2/5-HT1A receptor interactions can have on in vivo responses.

Taken together, these data provide a comprehensive in vitro picture of the agonist/antagonist activities of F15063 at 5-HT1A and D2 receptors, respectively, allowing interpretation of the influence of these pharmacological properties. Indeed, the combined D2/5-HT1A properties of F15063 account for many of the actions of F15063 in neurochemical and behavioural models in rodents. Thus, F15063 potently reversed apomorphine-induced climbing behaviour in mice and methylphenidate-induced behaviours in rats, two measures reflecting blockade of central dopamine D2 receptors (Depoortère et al., 2007a, 2007b). Conversely, the 5-HT1A agonist properties of F15063 in vivo are demonstrated by unmasking of catalepsy when 5-HT1A receptors are occluded by the selective antagonist, WAY100 635. Further, the 5-HT1A agonist properties of F15063 are responsible for the increase in extracellular levels of dopamine in the frontal cortex and attenuation of PCP-induced social interaction deficits by this compound (Newman-Tancredi et al., 2006; Depoortère et al., 2006, 2007a, 2007b).

F15063 blocks D3 receptors but activates D4 receptors in vitro

Whilst D2 antagonism and 5-HT1A agonism are key components of the profile of action of F15063, other activities make important contributions to its actions. Thus, F15063 possesses marked D3 receptor affinity (Table 5), at which it behaves as a potent antagonist (pKb=8.74, Figure 5). Blockade of D3 receptors is a common effect of antipsychotics, whether conventional or atypical (Joyce and Millan, 2005; Sokoloff et al., 2006) and considerable effort has been invested in examining the role of D3 antagonism in the actions of antipsychotics in pre-clinical models. While selective D3 antagonists do not show activity in rodent models of dopaminergic hyperstimulation (Millan et al., 2000; Reavill et al., 2000), the influence of BP897, a D3 partial agonist, in models of NMDA blockade in mice has raised the possibility that D3 interactions may contribute to antipsychotic efficacy (Leriche et al., 2003; Sokoloff et al., 2006). Recent reports have shown that selective D3 antagonists, S33084 and SB277011, increase acetylcholine release in rats and are active in models of scopolamine-induced cognitive deficits (Dekeyne et al., 2004; Laszy et al., 2005). Thus, the potent D3 blocking properties of F15063 may represent a favourable element in its cognitive profile.

A feature of F15063 that differentiates it from current antipsychotic agents is the combination of D2/D3 antagonist properties with partial agonism at the other member of the D2-like receptor family, the D4 subtype. Using an approach similar to that employed previously (Newman-Tancredi et al., 1997), F15063 exhibited modest stimulation of G-protein activation in CHO cell membranes expressing the 4-repeat isoform of the D4 receptor, while reducing dopamine-induced [35S]GTPγS binding, demonstrating partial agonist properties of F15063 at D4 receptors. In comparison, apomorphine, a drug that possesses substantial efficacy at D4 receptors (Newman-Tancredi et al., 1997) exhibited an Emax value no more than 1.5-fold greater than that of F15063. It is interesting that D4 receptor activation is implicated in pro-cognitive actions in rodents (Bernaerts and Tirelli, 2003; Browman et al., 2005). In contrast, some reports indicate that D4 receptor blockade is necessary for activity in other models of cognitive deficits (Jentsch et al., 1999). It may be that an intermediate (i.e. partial agonist) influence is necessary to provide the optimal profile of action, as suggested by some authors (Zhang et al., 2004). In the case of F15063, its reversal of scopolamine-induced memory deficit in a social recognition paradigm was completely abolished by pre-treatment with a D4 receptor antagonist, L745870 (Bardin et al., 2006b; Depoortère et al., 2006, 2007b). These results indicate that the D4 partial agonist properties of F15063 detected in vitro are reflected in an in vivo behavioural model of cholinergic deficits and suggest that incorporating D4 partial agonist properties in novel antipsychotic candidates could lead to improved influence on mnesic functions.

F15063 has minimal interaction at other monoamine receptors

A distinguishing feature of F15063 is its minimal interactions with a range of other receptors. In particular, F15063 has only modest affinity for h5-HT2A/2B/2C receptors (47- to 147-fold lower than at hD2 receptors) whereas atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone, olanzapine and ziprasidone have markedly higher affinity at these sites than at D2 receptors (Leysen, 2000). While blockade of 5-HT2A and/or 5-HT2C receptors is associated with anti-cataleptic properties and facilitation of cortical dopamine release (see Introduction), these desirable responses are also robustly induced by activation of 5-HT1A receptors, suggesting that a D2/5-HT1A profile may be sufficient to produce an ‘atypical' antipsychotic profile (Millan, 2000; Bantick et al., 2001; Meltzer et al., 2003). Interestingly, F15063 exhibited partial agonism for stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding at h5-HT1D receptors (Figure 6) with a potency (pEC50=7.68) similar to that for stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding at 5-HT1A receptors (pEC50=7.57; Table 6). In contrast, other antipsychotics, including clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol, display inverse agonism at 5-HT1D receptors (Audinot et al., 2001). Thus, activity at 5-HT1D receptors may play a role in the distinctive pharmacological profile of F15063, although the therapeutic relevance of this observation is unclear. Indeed, the in vivo responses to F15063 (Depoortère et al., 2007a, 2007b) can be satisfactorily attributed to actions at D2-like and 5-HT1A receptors. Further, the efficacy of F15063 at 5-HT1D receptors (Emax 35%, Table 6) is low relative to that of the antimigraine agents sumatriptan (87%) and dihydroergotamine (75%). The Emax of F15063 is also inferior to that of GR127935 (50%), a partial agonist that has little, if any, agonist activity in vivo (Skingle et al., 1996; De Vries et al., 1997). Taken together, these data suggest that the predominant action of F15063 at 5-HT1D receptors will be as an antagonist. While this is unlikely to constitute a prominent property of F15063, it underlines the latter's novel profile at monoamine receptors.

F15063 does not interact with a variety of sites associated with undesirable effects associated with current antipsychotics such as olanzapine and clozapine. These include antagonism of α1 adrenoceptors, muscarinic M1 receptors and histamine H1 receptors, sites associated with autonomic side effects, sedation, weight gain and potential metabolic disturbance. Thus a ‘selectively non-selective' profile, as displayed by F15063, may avoid a number of potential side effects, whilst retaining the desired pharmacological properties underlying efficacious antipsychotic actions (Leysen, 2000; Shapiro et al., 2003; Roth et al., 2004).

Conclusions

Abundant in vitro and in vivo results, together with clinical evidence from add-on studies with 5-HT1A receptor partial agonists, indicate that appropriate targeting of D2 and 5-HT1A receptors should produce a promising ‘atypical' antipsychotic with improved potential for the management of negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. However, a fundamental issue in the characterization of the new generation of antipsychotics is the definition of an ‘optimal balance' of activity at D2 and 5-HT1A receptors (see Assié et al., 2005; Bruins Slot et al., 2005; Newman-Tancredi et al., 2005; Bardin et al., 2006a, 2006b; Auclair et al., 2006a, 2006b). Thus, while potent D2/3 receptor antagonism is desirable for robust antipsychotic actions, the presence of sufficient 5-HT1A receptor activation should alleviate negative symptoms, favour cognitive function and diminish EPS liability. The potent D2/3 antagonist properties of F15063, combined with its less potent, but high efficacy, 5-HT1A receptor agonism and D4 receptor partial agonism confer on F15063 a novel profile. The absence of marked interactions of F15063 with targets associated with potential side effects, including histaminergic and muscarinic receptors suggests improved safety profile. In view of the favourable activity of F15063 in a series of in vivo models of positive, negative and cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia (Depoortère et al., 2006, 2007a, 2007b), it appears that its balance of receptor activities is promising for improved treatment of this pathology.

Acknowledgments

Nathalie Leduc, Nathalie Danty, Valérie Faucillon, Véronique Ravailhe, Nathalie Consul, Jérôme Rouquet, Anne-Marie Ormière, Sophie Bernois, Stéphanie Tardif and Marie-Christine Ailhaud are thanked for technical assistance. Elisabeth Carilla and Christine Aussenac are thanked for administrative assistance.

Abbreviations

- C6

rat glioma cells

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- COS7

African green monkey kidney cells

- DMEM

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- EPS

extrapyramidal symptoms

- ERK1/2

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- F15063

N-[(2,2-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-benzofuran-7-yloxy)ethyl]-3-(cyclopent-1-enyl)-benzylamine

- GTPγS

guanosine 5′-O-(gamma-thiotriphosphate)

- 5-HT

5-hydroxytryptamine, serotonin

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney cells

- HeLa

human carcinoma cells

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- Sf9

Spodoptera frugiperda insect cells

Conflict of interest

The present study was funded by Pierre Fabre Médicament. All authors are employees of the Centre de Recherche Pierre Fabre.

References

- Assié MB, Koek W. [3H]-8-OH-DPAT binding in the rat brain raphe area: involvement of 5-HT1A and non-5-HT1A receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1348–1352. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assié MB, Ravailhe V, Faucillon V, Newman-Tancredi A. Contrasting contribution of 5-HT1A receptor activation to neurochemical profile of novel antipsychotics: frontocortical DA and hippocampal serotonin release in rat brain. J Pharmacol Expt Ther. 2005;315:265–272. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.087163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auclair A, Newman-Tancredi A, Depoortère R. Comparative analysis of typical, atypical, and novel antipsychotics with preferential D2/D3 and 5-HT1A affinity in rodent models of cognitive flexibility and sensory gating: II) The reversal learning task and PPI of the startle reflex. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006a;9 Supp 1:P01.167. [Google Scholar]

- Auclair AL, Kleven MS, Besnard J, Depoortère R, Newman-Tancredi A. Actions of novel antipsychotic agents on apomorphine-induced PPI disruption: influence of combined serotonin 5-HT1A receptor activation and dopamine D2 receptor blockade. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006b;31:1900–1909. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audinot V, Newman-Tancredi A, Cussac D, Millan MJ. Inverse agonist properties of antipsychotic agents at cloned, human (h) serotonin (5-HT)1B and h5-HT1D receptors. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;25:410–422. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantick RA, Deakin JF, Grasby PM. The 5-HT1A receptor in schizophrenia: a promising target for novel atypical neuroleptics. J Psychopharmacol. 2001;15:37–46. doi: 10.1177/026988110101500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard JA, Zgombick J, Adham N, Vaysse P, Branchek TA, Weinshank RL. Cloning of a novel human serotonin receptor (5-HT7) positively linked to adenylate cyclase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23422–23426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin L, Kleven MS, Barret-Grévoz C, Depoortère R, Newman-Tancredi A. Antipsychotic-like vs cataleptogenic actions in mice of novel antipsychotics having D2 antagonist and 5-HT1A agonist properties. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006a;31:1869–1879. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin L, Newman-Tancredi A, Depoortère R. Comparative analysis of typical, atypical, and novel antipsychotics with preferential D2/D3 and 5-HT1A affinity in rodent models of cognition and memory deficits: (I) The hole-board and the social recognition tests. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006b;9 Suppl 1:P01.166. [Google Scholar]

- Bernaerts P, Tirelli E. Facilitatory effect of the dopamine D4 receptor agonist PD168,077 on memory consolidation of an inhibitory avoidance learned response in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003;142 1–2:41–52. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00371-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P, Ward NM. Is there a role for 5-HT1A agonists in the treatment of depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:193–203. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browman KE, Curzon P, Pan JB, Molesky AL, Komater VA, Decker MW, et al. A-412997, a selective dopamine D4 agonist, improves cognitive performance in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;82:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning JL, Patel T, Brandt PC, Young KA, Holcomb LA, Hicks PB. Clozapine and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway: implications for antipsychotic actions. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruins Slot L, De Vries L, Newman-Tancredi A, Cussac D. Differential profile of antipsychotics at serotonin 5-HT1A and dopamine D2S receptors coupled to extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;534:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruins Slot LA, Kleven MS, Newman-Tancredi A. Effects of novel antipsychotics with mixed D2 antagonist/5-HT1A agonist properties on PCP-induced social interaction deficits in the rat. Neuropharmacol. 2005;49:996–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celada P, Puig V, Armagos-Bosch M, Adell A, Artigas F. The therapeutic role of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors in depression. Rev Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29:252–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claustre Y, Peretti DD, Brun P, Gueudet C, Allouard N, Alonso R, et al. SSR181507, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist and 5-HT1A receptor agonist. I: Neurochemical and electrophysiological profile. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:2064–2076. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosi C, Carilla-Durand E, Assié MB, Ormière AM, Maraval M, Leduc N, et al. Partial agonist properties of the antipsychotics SSR181507, aripiprazole and bifeprunox at dopamine D2 receptors: G protein activation and prolactin release. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;535:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuisiat S, Bourdiol N, Lacharme V, Newman-Tancredi A, Colpaert F, Vacher B.Towards a new generation of potential anti-psychotic agents combining D2 and 5-HT1A receptor activities J Med Chem(in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cussac D, Duqueyroix D, Newman-Tancredi A, Millan MJ. Stimulation by antipsychotic agents of mitogen-activated-protein kinase (MAPK) coupled to cloned, human (h) serotonin (5-HT)1A receptors. Psychopharmacology. 2002a;162:168–177. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussac D, Newman-Tancredi A, Duqueyroix D, Pasteau V, Millan MJ. Differential activation of Gq/11 and Gi3 proteins at 5-hydroxytryptamine2C receptors revealed by antibody capture assays: Influence of receptor reserve and relationship to agonist-directed trafficking. Mol Pharmacol. 2002b;62:578–589. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cussac D, Newman-Tancredi A, Sezgin L, Millan MJ. The novel antagonist, S33084, and GR218,231 interact selectively with cloned and native rat dopamine D3 receptors as compared with native, rat dopamine D2 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;394:47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czyrak A, Czepiel K, Mackowiak M, Chocyk A, Wedzony K. Serotonin 5-HT1A receptors might control the output of cortical glutamatergic neurons in rat cingulate cortex. Brain Res. 2003;989:42–51. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM, Chen N, Glick ID. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:553–564. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries P, Apaydin S, Villalon CM, Heiligers JP, Saxena PR. Interactions of GR127935, a 5-HT(1B/D) receptor ligand, with functional 5-HT receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1997;355:423–430. doi: 10.1007/pl00004964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekeyne A, Di Cara B, Gobert A, Millan MJ. Blockade of dopamine D3 receptors enhances frontocortical cholinergic transmission and cognitive function in rats. Am Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2004;30:776.4. [Google Scholar]

- Depoortère R, Auclair AL, Bardin L, Bruins Slot L, Kleven M, Newman-Tancredi A.F15063, a compound with D2/D3 antagonist, 5-HT1A agonist and D4 partial agonist properties: (III) activity in models of cognition and negative symptoms Br J Pharmacol 2007a 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707160E-pub ahead of print: 20 March 2007doi [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Depoortère R, Bardin L, Auclair A, Bruins-Slot L, Kleven M, Newman-Tancredi A. F15063, an innovative antipsychotic with D2/D3 antagonist, 5-HT1A agonist and D4 partial agonist properties: (II) Behavioural profile in models of positive, negative symptoms and cognitive deficits of schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9 Supp 1:P01.165. [Google Scholar]

- Depoortère R, Bardin L, Auclair AL, Kleven M, Prinssen E, Newman-Tancredi A.F15063, a compound with D2/D3 antagonist, 5-HT1A agonist and D4 partial agonist properties: (II) Activity in models of positive symptoms of schizophrenia Br J Pharmacol 2007b 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707159E-pub ahead of print: 20 March 2007doi [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Depoortère R, Boulay D, Perrault G, Bergis O, Decobert M, Francon D, et al. SSR181507, a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist and 5-HT1A receptor agonist. II: behavioral profile predictive of an atypical antipsychotic activity. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1889–1902. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Mataix L, Scorza MC, Bortolozzi A, Toth M, Celada P, Artigas F. Involvement of 5-HT1A receptors in prefrontal cortex in the modulation of dopaminergic activity: role in atypical antipsychotic action. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10831–10843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2999-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargin A, Raymond JR, Regan JW, Cotecchia S, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Effector coupling mechanisms of cloned 5-HT1A receptor. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14848–14852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glennon AC, McCreary AC, Ronken E, Siarey R, Hesselink MB, Feenstra R, et al. SLV313 is a dopamine D2 receptor antagonist and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist: in vitro and in vivo neuropharmacology. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12 Suppl 3:P.2.053. [Google Scholar]

- Goff DC, Midha KK, Brotman AW, McCormick S, Waites M, Amico ET. An open trial of buspirone added to neuroleptics in schizophrenic patients. J Clin Psychoparmacol. 1991;11:193–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AL, Mallard NJ, Tyacke R, Nutt DJ. [3H]-RX821002: a highly selective ligand for the identification of α2-adrenoceptors in the rat brain. Mol Neuropharmacol. 1992;1:219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa J, Meltzer HY. The effect of serotonin1A receptor agonism on antipsychotic drug-induced dopamine release in rat striatum and nucleus accumbens. Brain Res. 2000;858:252–263. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02346-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Invernizzi RW, Cervo L, Samanin R. 8-Hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)-tetralin, a selective serotonin1A agonist, blocks haloperidol-induced catalepsy by an action of raphe nuclei medianus and dorsalis. Neuropharmacology. 1988;27:515–518. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(88)90134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Taylor JR, Redmond DE, Jr, Elsworth JD, Youngren KD, Roth RH. Dopamine D4 receptor antagonist reversal of subchronic phencyclidine-induced object retrieval/detour deficits in monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 1999;142:78–84. doi: 10.1007/s002130050865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan S, Chen R, Johnson J, Regardie K, Tadori Y, Kikuchi T. Aripiprazole is a potent, partial agonist at cloned human D2L and native rat 5-HT1A receptors. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12:S293. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce JN, Millan MJ. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists as therapeutic agents. Drug Disc Today. 2005;10:917–925. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss B, Laszlovsky I, Horvath A, Schmidt E, Bugovics GY, Orosz SZ, et al. RGH-188, an atypical antipsychotic with dopamine D3/D2 antagonist/partial agonist properties: in vitro characterisation. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9 Suppl 1:P02.213. [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS, Assie MB, Koek W. Pharmacological characterization of in vivo properties of putative mixed 5-HT1A agonist/5-HT(2A/2C) antagonist anxiolytics. II. Drug discrimination and behavioral observation studies in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:747–759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleven MS, Barret-Grévoz C, Bruins Slot L, Newman-Tancredi A. Novel antipsychotic agents with 5-HT1A agonist properties: role of 5-HT1A receptor activation in attenuation of catalepsy induction in rats. Neuropharmacol. 2005;49:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszy J, Laszlovszky I, Gyertyan I. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonists improve the learning performance in memory-impaired rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;179:567–575. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2096-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazareno S, Birdsall NJ. Estimation of antagonist Kb from inhibition curves in functional experiments: alternatives to the Cheng-Prusoff equation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:237–239. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90018-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leriche L, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. The dopamine D3 receptor mediates locomotor hyperactivity induced by NMDA receptor blockade. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45:174–181. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Wahlbeck K, Hamann J, Kissling W. New generation antipsychotics versus low-potency conventional antipsychotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2003;361:1581–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13306-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leysen J.Receptor profile of antipsychotics Atypical Antipsychotics 2000Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel, Switzerland; 57–81.In: Ellenbroek BA, Cools AR (eds) [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Ichikawa J, Dai J, Meltzer HY. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic drug, preferentially increases dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in rat brain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;493:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel JC, Ormière AM, Leduc N, Assié MB, Cussac D, Newman-Tancredi A. Native rat hippocampal 5-HT1A receptors show constitutive activity. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:638–643. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.029769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauler F, Fahrig T, Horvath E, Jork R. Inhibition of evoked glutamate release by the neuroprotective 5-HT1A receptor agonist BAY x 3702 in vitro and in vivo. Brain Res. 2001;888:150–157. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary AC, Glennon J, Tuinstra T, Herremans AHJ, Van der Heyden JAM, Feenstra R, et al. SLV313: a novel antipsychotic with additional antidepressant and anxiolytic-like actions. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;12 Suppl 3:P.2.046. [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Li Z, Kaneda Y, Ichikawa J. Serotonin receptors: their key role in drugs to treat schizophrenia. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:1159–1172. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer HY, Park S, Kessler R. Cognition, schizophrenia, and the atypical antipsychotic drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13591–13593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. Improving the treatment of schizophrenia: focus on serotonin 5-HT1A receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;295:853–861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]