Abstract

Background and purpose:

Liver X receptors (LXRs) activate genes that regulate lipid and cholesterol metabolism. LXR agonists were shown recently to also increase murine renin gene expression in vivo. To further examine a link between lipid metabolism, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone-system and blood pressure regulation, we investigated the effect of a LXR agonist (GW3965) on angiotensin II (Ang II)-mediated vasoreactivity and vascular angiotensin II receptor (ATR) gene expression.

Experimental approach:

Arterial blood pressure (BP) was measured during Ang II infusions (1.5 min duration; 0.001–3 μg kg−1) in pentobarbital-anesthetized male Sprague–Dawley rats (n = 6-9) after oral administration of GW3965 (10 mg kg−1, q.d.) or vehicle for 7 – 15 days. Mesenteric arteries and plasma were collected to analyze ATR gene expression and to measure plasma renin activity (PRA) and lipid profile, respectively.

Key results:

Basal mean arterial pressure (MAP) was similar between groups. GW3965 dosing blunted the vasopressor effect of Ang II, which was significantly different with the 0.3 and 3 μg kg−1 doses. No difference in heart rate, PRA or lipid profile was observed between groups. A time-course indicated that ATR type 1 and 2 gene expression of GW3965-treated vs. vehicle-treated rats decreased by 50%, reaching significance for ATR type 2, but not for ATR type 1, at time-points coinciding with BP measurements.

Conclusions and implications:

GW3965 decreased Ang II-mediated vasopressor responses coincident with a trend toward reduced ATR gene expression, suggesting that LXR agonists could affect vascular reactivity.

Keywords: liver X receptor, angiotensin II, angiotensin II receptor, blood pressure

Introduction

Liver X receptors (LXRs) are nuclear hormone receptors that activate genes involved in the regulation of cholesterol and lipid homeostasis (Tontonoz and Mangelsdorf, 2003). Oxidized derivatives of cholesterol (oxysterols) are endogenous ligands for LXRs (Janowski et al., 1996). Thus, elevated cellular cholesterol levels lead to accumulation of these cholesterol metabolic byproducts and activation of LXR target genes. LXRs activate genes involved in ‘reverse cholesterol transport' to increase transport of cholesterol from peripheral tissue to the liver for catabolism and excretion (Venkateswaran et al., 2000). Specifically, LXRs activate genes related to the cholesterol efflux system of macrophages (ATP binding cassette A1 and G1) and of other relevant plasma proteins, such as apolipoprotein E, phospholipids transfer protein, lipoprotein lipase and cholesterol ester transfer protein (Luo and Tall, 2000; Venkateswaran et al., 2000; Laffitte et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2001; Cao et al., 2002). Cholesterol homeostasis is additionally regulated by LXR-mediated gene induction to decrease dietary cholesterol absorption and to increase cholesterol metabolism and excretion from the body (Tontonoz and Mangelsdorf, 2003). LXRs also upregulate sterol regulatory binding protein-1c to cause lipogenesis leading to elevation of fatty acids (Peet et al., 1998; Schultz et al., 2000). LXRs are attractive therapeutic targets for their cholesterol lowering benefits, but the challenge is to develop gene-selective agonists without lipogenic effects.

LXR agonists were shown recently to increase murine renin gene expression in vivo suggesting a link between cholesterol and lipid metabolism, the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) and blood pressure regulation (Morello et al., 2005). Morello et al. (2005) demonstrated that LXRs regulate renin gene expression by interacting with a noncanonical response element (an overlapping region of cAMP and negative response elements) in the renin promoter. Most significantly, treatment with non-selective synthetic LXR agonists led to a transient upregulation of renin gene expression in mice. Changes in vasoreactivity, however, were not assessed.

To examine the potential role of LXRs in mediating cross-talk between lipid metabolism and cardiovascular function, we investigated the effect of a synthetic LXR agonist (GW3965; Collins et al., 2002) on angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced vasopressor responses and gene expression of vascular angiotensin receptors. GW3965 decreased ANG II-mediated vasopressor responses coincident with a trend toward reduced ATR gene expression, suggesting that agonists at the LXR could affect vascular reactivity.

Methods

In vivo

Ang II dose–response and blood pressure measurements

This animal study was approved by the Collegeville Animal Care and Use Committee of Wyeth Research and complies with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication No. 86-23). Male Sprague–Dawley rats (240–275 g) were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY, USA) and randomized according to body weight after a 72 h acclimatization period. Rats (n=6–9) were administered GW3965 (10 mg kg−1) or vehicle control (0.5% methylcellulose, 2% Tween-80) orally in a total volume of 1 ml, once a day for 7–15 days. Chronic dosing was used to evaluate longer-term effects of an LXR modulator on blood pressure regulation. GW3965 was synthesized at Wyeth Research.

Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg kg−1, intraperitoneally, Henry Schein Inc., Melville, NY, USA). The right carotid artery and jugular-vein were catheterized for blood pressure measurements and intravenous Ang II infusions, respectively. The carotid artery was cannulated with a saline-filled polyethylene catheter (PE 60) connected to a P23 ID Statham/Gould pressure transducer to monitor arterial pressure continuously. Ang II was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Data were recorded using PowerLab (MacLab system, AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO, USA). Heart rate was calculated from the blood pressure waveform.

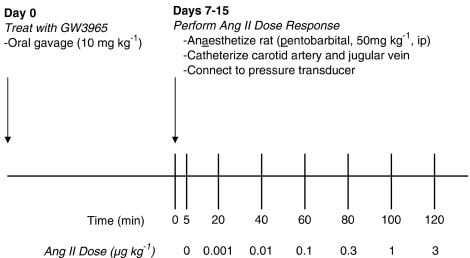

Blood pressure was measured continuously to obtain baseline measurements and changes in pressure during Ang II infusions. Increasing concentrations of Ang II (0.001–3 μg kg−1) were dosed as a single bolus adjusted to body weight (approx. 150 μl) followed by a saline flush (200 μl). Ang II was infused over 1.5 min to prevent tachycardia. Each dose was separated by a 20-min washout period (Figure 1). Sodium pentobarbital was supplemented as necessary. At the conclusion of the dose response, venous blood and tissue (liver, kidney and mesenteric vasculature) were collected. Whole blood was collected in EDTA-coated tubes. Plasma was isolated and frozen for measurement of plasma renin activity (PRA), cholesterol, triglycerides and lipoprotein fractions.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol to determine Ang II-mediated vasoconstriction following administration of vehicle or GW3965.

Vascular Ang II receptor gene expression time-course

To determine the effect of a LXR agonist on PRA and Ang II receptor gene expression without the confounding variable of Ang II, a second group of rats (260–305 g) were administered GW3965 (10 mg kg−1) or vehicle control for 7 days. On the seventh day of dosing, rats (n=4/group) were killed by CO2 asphyxiation at 1, 4, 6 and 8 h post-dosing. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture and liver, kidney and mesenteric vasculature were excised for gene expression analysis.

Ex vivo

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA extraction from mesenteric arteries was based on a previously published method (Rodrigo et al., 2002). Briefly, the mesenteric arcade was excised and immediately submerged in ice-cold RNA later (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The tissue was placed at 4°C overnight and then −20°C for a minimum of 3 days. Semi-frozen mesenteric arteries were isolated using a dissecting microscope while submerged under ice-cold RNAlater. Arteries were placed in Qiazol Lysis Buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) in preparation for RNA isolation and stored at −80°C until further processing. Tissues were homogenized with a Polytron rotor-stator homogenizer (Model: PT10-35, Kinematica AG, Westbury, NY, USA).

Mesenteric artery total RNAs were harvested using a protocol that combined Qiazol reagent and RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) protocols. A spectrophotometer was used to quantify RNA. Initial mesenteric artery RNA samples were resolved on an agarose gel to confirm that RNA was intact. Liver and kidney tissue were fast-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was homogenized in Qiazol reagent and RNAs were harvested according to standard methods using RNeasy Mini Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Real-time, quantitative RT-PCR using sequence-specific probes was performed on an ABI PRISM 7700 sequence detector using QuantiTect probe RT-PCR kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. Taqman primer sets were designed using Primer Express computer software (Applied BioSystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Data. Nonrelevant genes (18s and GAPDH) were used as controls. Gene expression data are expressed as relative fold changes in gene expression normalized to 18s or GAPDH.

Determination of PRA and lipids

Plasma was analyzed for PRA using a commercial radioimmunoassay (GammaCoat [125I] Plasma Renin Activity RIA Kit, DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN, USA). PRA was indirectly determined using a competitive binding assay to quantify angiotensin I generated from the plasma sample. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, except all reagent volumes were halved.

Plasma cholesterol and triglycerides were determined with a Hitachi 912 clinical autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). FPLC gel filtration chromatography was used to separate and determine lipoprotein fractions.

Statistical analysis

Blood pressure results represent data collected from two separate animal studies. Data were combined for a total of six to nine animals per treatment group. Blood pressure results are expressed as a change in peak mean arterial (MAP), systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) recorded in the 3-min period before and after Ang II challenge. Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. Statistical significance was determined using two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-tests.

PRA, lipid and gene expression data were analyzed by unpaired t-test. Gene expression data are presented as fold changes normalized to control. For time-course data, each time-point was normalized to the control and analyzed independently. Differences between means were considered statistically significant when P<0.05.

Results

Ang II dose–response and blood pressure study

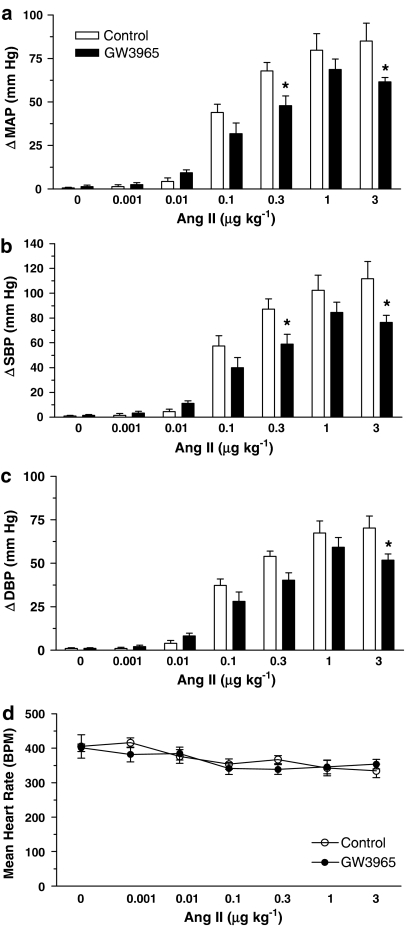

Body weight was similar in both treatment groups after a minimum of seven GW3965 doses (Table 1). Basal MAP was not different between vehicle control- and GW3965-treated rats (117±5 vs 131±6 mm Hg, P=0.09). GW3965 dosing blunted Ang II-induced changes in MAP, SBP and DBP (Figure 2). The reduced pressor response was significantly different with the 0.3 and 3 μg kg−1 doses for changes in MAP and SBP and significant with the 3 μg kg−1 for DBP. The reduced vasopressor response was not accompanied by changes in heart rate. Vehicle control- and GW3965-treated rat heart rates were similar at the time of blood pressure measurement (Figure 2d) and the rate pressure product was not significantly different between groups (data not shown).

Table 1.

Body weight, plasma renin activity, cholesterol, LDL, HDL, VLDL, and triglycerides in Ang II-infused rats treated orally with vehicle or GW3965 (10 mg kg−1), after a minimum 7-day treatment

| Parameter | Vehicle | GW3965 |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight (g) | 329±8 | 316±10 |

| Plasma renin activity (ng ml−1 day−1) | 8.1±3.1 | 4.8±1.4 |

| Cholesterol (mM) | 1.26±0.10 | 1.23±0.04 |

| LDL cholesterol (mM) | 0.42±0.03 | 0.49±0.03 |

| HDL cholesterol (mM) | 0.70±0.04 | 0.67±0.05 |

| VLDL cholesterol (mM) | 0.14±0.05 | 0.07±0.03 |

| Triglycerides (mM) | 0.24±0.06 | 0.15±0.05 |

Abbreviations: HDL, high-density lipoprotein, LDL, low-density lipoprotein, VLDL, very-low-density lipoprotein.

Figure 2.

GW3965 blunted the hypertensive effect of Ang II, which was significantly different with the 0.3 and 3 μg kg−1 doses for changes in MAP (a) and SBP (b) and significant with 3 μg kg−1 for DBP (c). Heart rates in control and GW3965-treated rats were similar at the time of blood pressure measurement (d). Results are mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05 vs control.

PRA, lipids and gene expression

To investigate a mechanism for reduced vasoreactivity in drug-treated rats, plasma lipid levels and renin activity as well as vascular angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) and 2 (AT2) receptor gene expression were determined. No difference in PRA was observed between vehicle and drug-treated animals (8.1±3.1 vs 4.8±1.4 ng ml−1 h−1, P>0.05). The lipid profile was similar for both treatment groups (Table 1).

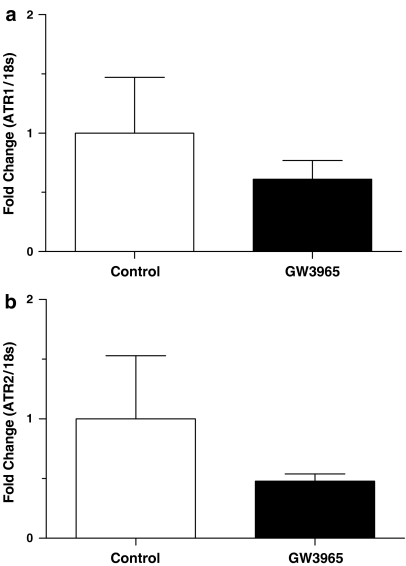

Vascular Ang II receptor gene expression of GW3965-treated animals trended toward a reduction, but did not reach significance (Figure 3). The gene expression data were extremely tight for drug-treated animals, whereas there was a great deal of variability in control samples. There was no difference between vehicle control and GW3965 groups in fold gene expression of kidney renin (1.0±0.1 vs 0.9±0.1, P>0.05) or AT1 and AT2 receptors (1.0±0.3 vs 1.0±0.2, P>0.05 and 1.0±0.2 vs 0.9±0.1, P>0.5, respectively).

Figure 3.

GW3965 treatment caused a trend toward a reduction in vascular Ang II receptor gene expression. Mean AT1 (a) and AT2 (b) receptor gene expression was 40 and 50%, respectively, lower in drug-treated as compared to control animals, but this effect was not statistically significant. Results are mean±s.e.m.

Vascular Ang II receptor gene expression time-course study

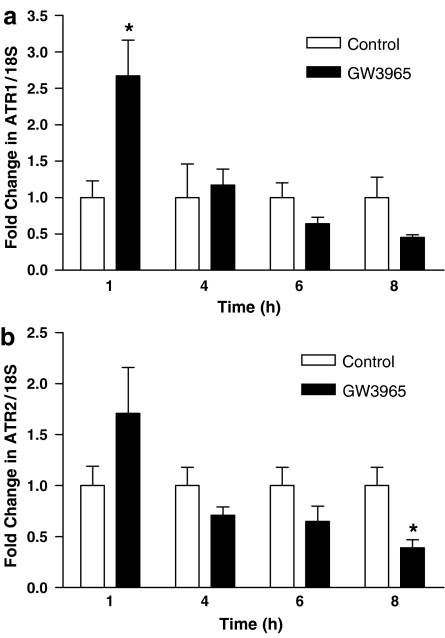

A second animal study was performed to determine the significance of the trend toward a reduction in vascular gene expression of Ang II receptors after administration of GW3965. Rats were dosed for 7 days and killed on the final day at 1, 4, 6 and 8 h post-dosing. GW3965 dosing caused an immediate, significant increase in AT1 receptor gene expression relative to control at the 1-h time point (Figure 4). Upregulation of vascular Ang II receptor gene expression was transient and decreased over time in drug-treated as compared to vehicle control animals. At the 8-h time point, which approximated the conclusion of the blood pressure study relative to dosing, AT1 and AT2 receptor gene expression of drug-treated rats decreased 50%, reaching significance for AT2, but not for AT1. To confirm LXR activation by GW3965, gene expression of cholesterol 7-α-hydroxylase (CYP7a; a LXR-target gene in rodents) was measured in liver tissue. CYP7a gene expression was significantly elevated in GW3965-treated rats at 4 h as compared to both treatments at all other time points (P<0.001, data not shown) and gradually decreased to control levels at 8 h, confirming LXR activation. These data strengthen our preliminary observation of a trend of decreased Ang II receptor gene expression following LXR treatment and suggest a mechanism for the reduced Ang II-induced vasopressor response.

Figure 4.

Vascular ATR1 gene expression was significantly elevated immediately following dosing with GW3965 and then decreased over time. At 8 h, mean ATR1 gene expression trended toward a 50% reduction in drug- vs control-treated animals (a). Drug-treated animals had significantly less vascular ATR2 gene expression than control at the 8-h time point (b). Results are mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05 vs control.

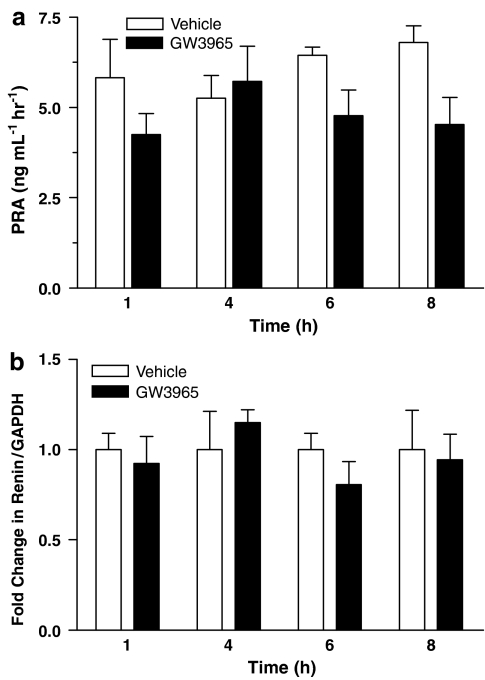

PRA, lipids and renin gene expression

As in the functional study, additional parameters were analyzed to determine a mechanism for Ang II receptor gene regulation. Figure 5a shows that PRA was similar in both treatment groups at all time points, although there was a trend toward lower PRA values for the GW3965 group at 1, 6 and 8 h. Correspondingly, at all time points kidney renin gene expression was not different between control and GW3965-treated animals (Figure 5b). Plasma lipid levels were not different at 8 h when the trend towards reduced Ang II receptor gene expression was observed (data not shown).

Figure 5.

PRA (a) and kidney renin gene (b) expression were not significantly different following administration of GW3965, suggesting that the RAAS was not activated to compensate for changes in vascular Ang II receptor gene expression.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrated that a synthetic LXR agonist, GW3965, reduced Ang II-mediated increases in blood pressure accompanied by a trend toward decreased vascular Ang II receptor gene expression. These novel findings suggest a role for LXRs as key players in lipid metabolism, the RAAS and blood pressure regulation.

Current research has focused on establishing a link between lipid disorders and cardiovascular disease. A potential role for LXR in mediating this cross talk was suggested recently on demonstration that LXRs regulate renin gene transcription by binding to a noncanonical response element in the renin promoter (Morello et al., 2005). More significantly, these authors showed that a single administration of LXR agonists produced a transient increase in murine renin gene expression suggesting potential physiological significance. Changes in vasoreactivity, however, were not assessed.

We show for the first time that a LXR agonist reduced Ang II-induced increases in blood pressure. Diminished vascular responsiveness to Ang II administration was associated with a trend toward downregulation of vascular AT1 and AT2 receptor gene expression. AT1 receptor stimulation primarily mediates changes in vascular function related to activation of the RAAS (Griendling et al., 1993). Several studies show that AT1 receptor mRNA and protein levels reflect one another and, furthermore, correspond to contraction upon Ang II infusion (Nickenig et al., 1997a, 1998, 1999). Therefore, AT1 receptor downregulation is a likely mechanism for diminished vasoreactivity upon Ang II infusions in GW3965-treated rats. It is important to emphasize that the 6–8-h time points, which were characterized by a trend toward decreased Ang II receptor gene expression, coincide with the timing of the observed reduction in Ang II-mediated blood pressure. If these data are combined to increase sample size, Ang II receptor gene expression is significantly reduced in the drug-treated group relative to control. Together these data suggest that reduced vascular function was related to the trend toward downregulation of AT1 receptor gene expression.

Interestingly, AT2 receptor gene expression was significantly reduced at the final time point. AT2 receptor activation is considered to counter AT1 receptor-mediated actions, leading to inhibition of cell proliferation and differentiation (Meier et al., 2005). Decreased AT2 receptor gene expression in drug-treated animals may seem surprising. However, one explanation for this observation may be that AT2 receptor actions are prominent in situations where AT1 receptor actions are increased. In this situation, since AT1 receptor gene expression is already downregulated, AT2 receptor gene expression may not be critical. Another explanation could be that additional signals, perhaps reactive oxygen species or inflammatory mediators, are necessary for upregulation of AT2 receptor and its subsequent beneficial receptor-mediated effects. It would be interesting to perform a similar study in the presence of an inflammatory component, such as a high fat diet, to determine the role of LXR agonism in AT2 receptor gene expression under pathogenic conditions. However, activation of the LXR caused a trend toward downregulation of Ang II receptors. This, along with a previously described role of LXR in stimulating reverse cholesterol transport, underscores the beneficial effects of LXR modulators for the treatment of atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases.

Ang II receptor gene regulation via an LXR pathway would be an interesting link between cholesterol homeostasis and cardiovascular disease. The mechanism for Ang II receptor gene regulation could be mediated directly or indirectly by LXR. A literature search revealed no data to support a LXR response element in the promoter of either Ang II receptor, making it unlikely that LXR is directly altering Ang II receptor gene expression. The reason for immediate and transient upregulation of AT1 receptors is not known at this time. It is the downregulation of Ang II receptor gene expression over time, coinciding with reduced vasoreactivity, which is more interesting from a pharmaceutical standpoint. This trend toward a reduction in Ang II receptor gene expression could be caused by a feedback mechanism resulting from the initial increase in Ang II receptor gene expression. This possibility, however, is unlikely because neither renin gene expression nor PRA were altered to suggest RAAS regulation in response to changes in Ang II receptor gene expression.

It is well documented that cholesterol can modulate Ang II receptor gene expression. Nickenig's laboratory has demonstrated low-density lipoprotein mediated upregulation of Ang II receptor gene expression with corresponding enhancement of reactivity in vascular smooth muscle (Nickenig et al., 1997b, 1997c). Additionally, hypercholesterolemic men treated with statins had decreased plasma cholesterol levels associated with reduced AT1 receptor activation and density (Nickenig et al., 1999). Although plasma cholesterol was correlated with reduced AT1 receptor function and density, these observations could result from lipid-independent effects of statin treatment. In our study, however, altered plasma lipid levels are not a likely explanation for the observed vascular Ang II receptor downregulation because there was no difference in plasma lipid profiles between treatment groups, which is in agreement with previous reports on GW3965 (Miao et al., 2004).

The most likely explanation for the trend toward downregulation of Ang II receptor gene expression is LXR-mediated repression of inflammatory genes. In addition to their well-known role in cholesterol metabolism, LXRs are important regulators of inflammatory signaling (Zelcer and Tontonoz, 2006). LXRs have been shown to downregulate inflammatory gene expression following stimulation with inflammatory mediators, such as tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β (Joseph et al., 2003). Many of these inflammatory genes are pro-atherogenic, including matrix metalloproteinase-9 and tissue factor, which are decreased in aorta of chronic animal models of atherosclerosis following activation of the LXR (Joseph et al., 2003; Terasaka et al., 2005). The Ang II receptor has inflammatory properties in addition to its classic effects on blood pressure and salt-volume homeostasis (Dagenais and Jamali, 2005). Recently, it has been accepted to play a more important role in the development of atherosclerosis through the production of reactive oxygen species and cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia (Nickenig, 2002). This would suggest that synthetic LXR agonists, in addition to increasing reverse cholesterol transport, might prevent atherosclerosis through Ang II receptor downregulation, and thereby decrease local inflammatory processes.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to demonstrate that a synthetic LXR agonist modulates vascular function. These studies were prompted by the recent observation by Morello et al. (2005) that synthetic LXR agonists transiently increased renin gene expression. In their study, mice on a normal diet were orally administered an LXR agonist (T0901317, 50 mg kg−1 or GW3965, 10 mg kg−1) or a single dose of vehicle (0.75% carboxymethylcellulose) and tissue was collected 4, 6 and 8 h post-dosing for RNA isolation. Renin as well as LXR target genes were upregulated in drug-treated compared to control animals. Renin gene expression doubled by 6 h, but subsequently decreased. In contrast, we observed no difference in renin gene expression between vehicle and treatment groups. These conflicting results may be owing to species variation (mouse vs rat), vehicle differences (0.75% carboxymethylcellulose vs 0.5% methylcellulose, 2% Tween-80) or duration of treatment. The study by Morello et al. (2005) entailed a single administration of drug whereas our study design involved chronic dosing. Therefore, additional studies will be necessary to determine LXRs' role in renin gene expression.

Our results complement research demonstrating that peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) activators decrease Ang II-induced blood pressure and modulate mesenteric Ang II receptor expression (Diep et al., 2002). Sprague–Dawley rats receiving subcutaneous Ang II plus a PPAR-γ activator for seven days had decreased AT1 and increased AT2 receptor gene expression as compared to control. Treatment with a nuclear hormone receptor agonist, as in our study, led to a decrease in AT1 receptor gene expression, but unlike our observations, an increase in AT2 receptor gene expression. AT2 upregulation probably resulted from activation of additional signaling pathways owing to co-treatment with angiotensin II, a pro-inflammatory mediator. Collectively, these studies strengthen a role for nuclear hormone receptors, typically considered mediators of lipid, glucose and cholesterol homeostasis, as important links between metabolism, the RAAS and cardiovascular disease.

One limitation of this study was measurement of blood pressure in anesthetized animals. Although it is best to make blood pressure measurements in conscious animals, our observation of a reduced Ang II-mediated pressor response in GW3965-treated animals is convincing. In our study we performed an Ang II dose-response to measure vasoreactivity, which remains intact, regardless of central depression, in the anesthetized animal. Furthermore, the trend toward decreased Ang II receptor gene expression suggests a mechanism for the blunted response and offers validity to our functional observations.

GW3965 dosing blunted Ang II-induced changes in MAP, SBP and DBP and significantly inhibited the vasopressor response at the highest dose of Ang II. To further investigate the specificity of this LXR-mediated response, a shortened, 3-day dosing study was recently performed using Tularik (10 mg kg−1; unpublished experiments). There was a trend toward reduced percent changes in mean blood pressure for Tularik-treated animals compared to vehicle control. We speculate that a longer dosing period (7 rather than 3 days) of Tularik would reduce Ang II-induced increases in blood pressure in a manner similar to that of GW3965 treatment. Additional long-term studies using an LXR agonist of a different structural class will be necessary to confirm the role of LXR in the reduced Ang II-induced increases in blood pressure.

Additional studies are also necessary to clarify the mechanism of LXR regulation of AT1 receptor gene expression. A single in vitro experiment demonstrated no effect of LXR-modulators (0.03, 0.3 and 3 μM GW3965 or Tularik) on AT1 receptor gene expression, relative to media control, in human aortic smooth muscle cells (unpublished experiments). There was, however, a dose-dependent increase in ABCA1 (a LXR-target gene) gene expression with a four-fold increase at the highest treatment concentrations of Tularik and GW3965. The absence of an AT1 receptor effect may be owing to (1) species differences (rat vs human), (2) vascular location (mesenteric arteries vs aorta) and (3) effects of systemic mediators not present in cell culture. The difference in gene expression of AT1 receptor and ABCA1 may be owing to different time courses of induction. Analysis of AT1 receptor protein expression for in vitro, as well as in vivo, studies would provide additional insight into LXR regulation of AT1 receptor and Ang II-mediated pressor responses. The mechanistic link between LXR gene regulation and the RAAS is unclear. Future research should focus on understanding this complex relationship.

In conclusion, we demonstrate reduced Ang II-mediated hypertension and a trend toward decreased Ang II receptor gene expression with a synthetic LXR agonist in Sprague–Dawley rats. These novel findings support a role for LXRs as a link between lipid metabolism, the RAAS and blood pressure regulation. Further investigation is necessary to determine if these effects are direct or indirect effects of LXR activation.

External data objects

Abbreviations

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- ATR

angiotensin II receptor

- DBP

diastolic blood pressure

- LXR

liver X receptor

- MAP

mean arterial blood pressure

- PPAR-γ

peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-gamma

- PRA

plasma renin activity

- RAAS

renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

Conflict of interest

All the authors were employed by Wyeth Research during this study.

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Pharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/bjp)

References

- Cao G, Beyer TP, Yang XP, Schmidt RJ, Zhang Y, Bensch WR, et al. Phospholipid transfer protein is regulated by liver X receptors in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:39561–39565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207187200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JL, Fivush AM, Watson MA, Galardi CM, Lewis MC, Moore LB, et al. Identification of a nonsteroidal liver X receptor agonist through parallel array synthesis of tertiary amines. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1963–1966. doi: 10.1021/jm0255116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais NJ, Jamali F. Protective effects of angiotensin II interruption: evidence for antiinflammatory actions. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25:1213–1229. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.9.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep QN, El Mabrouk M, Cohn JS, Endemann D, Amiri F, Virdis A, et al. Structure, endothelial function, cell growth, and inflammation in blood vessels of angiotensin II-infused rats: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Circulation. 2002;105:2296–2302. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000016049.86468.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griendling KK, Murphy TJ, Alexander RW. Molecular biology of the renin-angiotensin system. Circulation. 1993;87:1816–1828. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.6.1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski BA, Willy PJ, Devi TR, Falck JR, Mangelsdorf DJ. An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR alpha. Nature. 1996;383:728–731. doi: 10.1038/383728a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph SB, Castrillo A, Laffitte BA, Mangelsdorf DJ, Tontonoz P. Reciprocal regulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism by liver X receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nm820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffitte BA, Repa JJ, Joseph SB, Wilpitz DC, Kast HR, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. LXRs control lipid-inducible expression of the apolipoprotein E gene in macrophages and adipocytes. PNAS. 2001;98:507–512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.021488798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Tall AR. Sterol upregulation of human CETP expression in vitro and in transgenic mice by an LXR element. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:513–520. doi: 10.1172/JCI8573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier P, Maillard M, Burnier M. The future of angiotensin II inhibition in cardiovascular medicine. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2005;5:15–30. doi: 10.2174/1568006053004994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao B, Zondlo S, Gibbs S, Cromley D, Hosagrahara VP, Kirchgessner TG, et al. Raising HDL cholesterol without inducing hepatic steatosis and hypertriglyceridemia by a selective LXR modulator. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1410–1417. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300450-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello F, de Boer RA, Steffensen KR, Gnecchi M, Chisholm JW, Boomsma F, et al. Liver X receptors alpha and beta regulate renin expression in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1913–1922. doi: 10.1172/JCI24594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickenig G. Central role of the AT(1)-receptor in atherosclerosis. J Hum Hypertens. 2002;16 Suppl 3:S26–S33. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickenig G, Baumer AT, Grohe C, Kahlert S, Strehlow K, Rosenkranz S, et al. Estrogen modulates AT1 receptor gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Circulation. 1998;97:2197–2201. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.22.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickenig G, Baumer AT, Temur Y, Kebben D, Jockenhovel F, Bohm M. Statin-sensitive dysregulated AT1 receptor function and density in hypercholesterolemic men. Circulation. 1999;100:2131–2134. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.21.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickenig G, Jung O, Strehlow K, Zolk O, Linz W, Scholkens BA, et al. Hypercholesterolemia is associated with enhanced angiotensin AT1-receptor expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1997a;272:H2701–H2707. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickenig G, Sachinidis A, Michaelsen F, Bohm M, Seewald S, Vetter H. Upregulation of vascular angiotensin II receptor gene expression by low-density lipoprotein in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1997b;95:473–478. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickenig G, Sachinidis A, Seewald S, Bohm M, Vetter H. Influence of oxidized low-density lipoprotein on vascular angiotensin II receptor expression. J Hypertens Suppl. 1997c;15:S27–S30. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715066-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet DJ, Turley SD, Ma W, Janowski BA, Lobaccaro JM, Hammer RE, et al. Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Cell. 1998;93:693–704. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo MC, Martin DS, Redetzke RA, Eyster KM. A method for the extraction of high-quality RNA and protein from single small samples of arteries and veins preserved in RNAlater. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2002;47:87–92. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(02)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JR, Tu H, Luk A, Repa JJ, Medina JC, Li L, et al. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2831–2838. doi: 10.1101/gad.850400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terasaka N, Hiroshima A, Ariga A, Honzumi S, Koieyama T, Inaba T, et al. Liver X receptor agonists inhibit tissue factor expression in macrophages. FEBS J. 2005;272:1546–1556. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Mangelsdorf DJ. Liver X receptor signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:985–993. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkateswaran A, Laffitte BA, Joseph SB, Mak PA, Wilpitz DC, Edwards PA, et al. Control of cellular cholesterol efflux by the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXRalpha. PNAS. 2000;97:12097–12102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200367697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelcer N, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:607–614. doi: 10.1172/JCI27883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Repa JJ, Gauthier K, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of lipoprotein lipase by the oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43018–43024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.