Abstract

Background and purpose:

Studies suggest that measurement of thermodynamic parameters can allow discrimination of agonists and antagonists. Here we investigate whether agonists and antagonists can be thermodynamically discriminated at histamine H3 receptors.

Experimental approach:

The pKL of the antagonist radioligand, [3H]-clobenpropit, in guinea-pig cortex membranes was estimated at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C in 20mM HEPES-NaOH buffer (buffer A), or buffer A containing 300mM CaCl2, (buffer ACa). pKI′ values for ligands with varying intrinsic activity were determined in buffer A and ACa at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C.

Key results:

In buffer A, the pKL of [3H]-clobenpropit increased with decreasing temperature while it did not change in buffer ACa. The Bmax was not affected by temperature or buffer and n H values were not different from unity. In buffer A, pKI′ values for agonists remained unchanged or decreased with decreasing temperature, while antagonist pKI values increased with decreasing temperature; agonist binding was entropy-driven while antagonist binding was enthalpy and entropy-driven. In buffer ACa, temperature had no effect on antagonist and agonist pKI values; both agonist and antagonist binding were enthalpy and entropy-driven.

Conclusions and implications:

The binding of H3-receptor agonists and antagonists can be thermodynamically discriminated under conditions where agonist pKI′ values are over-estimated (pKI′≠pKapp). However, under conditions when agonist pKI ∼pKapp, the thermodynamics underlying the binding of agonists are not different to those of antagonists.

Keywords: [3H]clobenpropit, histamine H3-receptors

Introduction

Radioligand-binding assays, second messenger assays and functional in vitro bioassays are used to provide receptor-affinity estimates (pKI and pKb) for novel ligands. Although these estimates are valuable in the development of high affinity, selective receptor antagonists, they provide little information about the molecular mechanisms underlying the ligand–receptor interaction. However, it is possible to obtain information about these interactions by performing thermodynamic studies in which the receptor affinity of the ligand is determined at a number of different temperatures (see Hitzeman, 1988; Raffa and Porreca, 1989).

The value of thermodynamics for investigating receptor–ligand interactions has been demonstrated in numerous studies (Weiland et al., 1979; Mohler and Richards, 1981; Zahniser and Molinoff, 1983; Reith et al., 1984; Kilpatrick et al., 1986; Testa et al., 1987; Todd and Babinski, 1987; Aronstam and Narayanan, 1988; Duarte et al., 1988; Borea et al., 1996a, 1996b; Dalpiaz et al., 1996; Maguire and Loew, 1996; Li et al., 1998). In addition, some of these studies have suggested that measurement of thermodynamic parameters can allow the discrimination of agonist and antagonist ligands (Weiland et al., 1979; Zahniser and Molinoff, 1983; Borea et al., 1996a).

There has been no thermodynamic analysis of ligand binding at the histamine H3-receptor. Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to determine whether the binding of ligands, characterised as agonists and antagonists at histamine H3-receptor in a functional bioassay of the guinea-pig ileum, could be discriminated thermodynamically. However, in previous studies, we have shown that agonist affinity values are overestimated in H3-receptor radioligand-binding assays conducted in the absence of buffer salts by an amount which is related to the ligand's intrinsic activity (see Harper et al., 2007) and, additionally, that when radioligand-binding assays are conducted in the presence of salts, pKI estimates are closer to pKapp values estimated by the method of Furchgott in a guinea-pig ileum bioassay. Therefore, an additional aim of this study was to establish whether the thermodynamic parameters underlying the binding interaction of agonists paralleled those of the antagonists, when the assay was conducted under conditions where their pKI values were similar to pKapp values and where the agonist nH values were not different from unity.

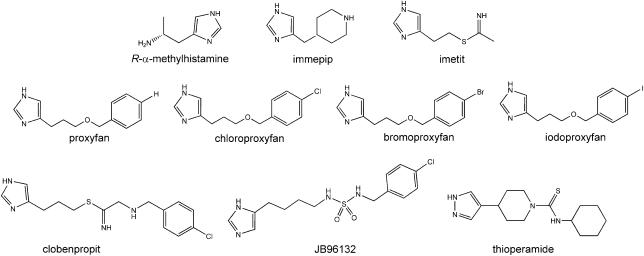

The agonist ligands that were selected for this study had varying intrinsic activity (α) as defined by bioassay on the guinea-pig ileum myenteric plexus longitudinal muscle (see Figure 1 and Harper et al., 2007) (immepip, α=1.0; imetit, α=0.90; R-α-methylhistamine (R-α-MH), α=1.0; proxyfan, α=0.35; chloroproxyfan α=0.45; bromoproxyfan α=0.65; and iodoproxyfan, α=0.90). The antagonist ligands, as defined by bioassay (thioperamide, JB96132 and [3H]clobenpropit), all contained an imidazole moiety (Figure 1 and Harper et al., 2007).

Figure 1.

Structure of histamine H3-receptor agonist and antagonist ligands.

A preliminary account of some of these data was presented to the British Pharmacological Society (Harper et al., 2002).

Methods

Preparation of guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes

Adult male Dunkin–Hartley guinea-pigs (200–300 g) were killed by cervical dislocation and the whole brain removed and immediately placed in ice-cold 20 mM HEPES–NaOH buffer (buffer A; pH 7.4 at 21±3°C). The cortex was dissected, weighed and homogenised in ice-cold buffer A (1 g 15 ml−1) using a polytron homogeniser (Kinematica AG, Gmbh, Lucerne, Switzerland; PT-DA 3020/2TS; ∼3 s × 3). The homogenate was centrifuged (100 g, 5 min at 4°C) and the supernatants pooled and stored at 4°C. The pellets were rehomogenised in ice-cold buffer A (80 ml) and re-centrifuged (100 g, 5 min at 4°C). The supernatants were centrifuged (39 800 g, 12 min at 4°C) and the final pellet was resuspended in buffer A (containing 3 mM metyrapone; at 4, 12, 21 or 30°C) to the required tissue concentration using a Teflon-in-glass homogeniser. Metyrapone was included in the assay buffer because this prevents [3H]clobenpropit binding to cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (see Harper et al., 1999b).

[3H]clobenpropit: tissue-concentration studies

Previous studies have indicated that, when using [3H]-clobenpropit to label histamine H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes at 21°C, 1.6 mg of membranes is optimal (Harper et al., 1999b). However, before investigating whether incubation temperature had any effect on the estimated affinity (pKL) of [3H]-clobenpropit, it was necessary to confirm that this was also the optimal membrane concentration for studies at 4, 12 and 30°C.

Guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes (0.2–4 mg) were incubated (2.75 h at 21 and 30°C; 24 h at 4 and 12°C) with [3H]-clobenpropit (0.2 nM) and buffer A in a final assay volume of 0.5 ml. Total binding was defined with buffer A and non-specific binding with 1 μM thioperamide (pKI at histamine H3-receptors in guinea-pig cortex ∼9.1, Harper et al., 1999a). The assay was terminated by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/B filters, pre-soaked in 0.3% polyethyleneimine (PEI), that were washed (3 × 3 ml) with ice-cold 50mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4 at 4°C) using a Brandell Cell Harvester. Filters were transferred into scintillation vials, 4 ml Meridian Gold-Star liquid scintillation cocktail added, and after 3 h, the bound radioactivity was determined by counting (3 min) in a Beckman liquid scintillation counter.

[3H]clobenpropit: saturation studies

Guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes (1.6 mg) were incubated (2.75 h at 21 and 30°C; 24 h at 4 and 12°C) in a final assay volume of 0.5 ml with buffer A and 0.004 to 3 nM [3H]clobenpropit. Total and non-specific binding were defined using buffer A and thioperamide (1 μM).

In an additional series of experiments, we investigated the effect of temperature (4, 12, 21 and 30°C) on the binding of [3H]clobenpropit in the presence of 300 mM CaCl2 (buffer ACa). This was because in previous studies, we found that this buffer was more effective than 100 mM NaCl, 100 mM KCl and 70 mM CaCl2 at reducing R-α-MH pKI values to those equivalent to pKapp values estimated in a functional bioassay; see Harper et al., 2007).

[3H]clobenpropit: kinetic studies

The observed association rate was determined at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C by incubating [3H]clobenpropit (0.2 nM) for increasing time intervals (0.25–150 min), in a final assay volume of 0.5 ml, in six tubes containing membranes (1.6 mg) and either buffer A or 1 μM thioperamide.

The dissociation rate and t1/2 for [3H]clobenpropit was ascertained by adding 10 μl of 50 μM thioperamide to three tubes in which membranes (1.6 mg) had been incubated (4°C, 220 min; 12°C, 150 min; 21°C, 150 min; 30°C, 120 min) with [3H]clobenpropit (0.2 nM). The bound radioligand was determined at increasing incubation times (0.5–400 min).

Competition studies

Guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes, resuspended in either buffer A or buffer ACa, (1.6 mg) were incubated with [3H]clobenpropit (0.2 nM) and competing compound, in a final assay volume of 0.5 ml, for 2.75 h at 30 and 21°C and for 24 h at 12 and 4°C (at least 5 × t1/2; [3H]clobenpropit at each temperature). Total and non-specific binding of [3H]clobenpropit were defined using buffer A or ACa and 1 μM thioperamide, respectively.

Data analysis

All data are presented as the mean±s.e.m. unless stated otherwise.

Saturation data

The Hill equation was fitted to saturation data (equation (2)) using GraphPad prism software with the Hill slope (nH) constrained to unity and with nH unconstrained.

|

In this equation, L is the radioligand concentration, Bmax is the receptor density and KL is the equilibrium dissociation constant of the radioligand.

Kinetic data

Association and dissociation data were analysed using GraphPad prism software.

Radioligand binding: competition curve data

To obtain pIC50 and nH parameter estimates, competition data were fitted to the Hill equation and to the Hill equation with nH constrained to unity, using GraphPad Prism software. Notwithstanding the finding of nH values that were significantly less than unity, dissociation constants (pKI) were subsequently determined from pIC50 values using the Cheng and Prusoff (1973) equation to correct for the different receptor occupancy of [3H]clobenpropit in the different buffers at the different temperatures. The parameter pKI′ has been assigned to dissociation constants which were derived from pIC50 values, where competition curve nH parameter estimates were significantly less than unity. The pKL values which were used to correct pIC50 values obtained in buffer A at 4, 12 21 and 30°C are shown in Table 1 and were 10.57, 10.38, 10.40 and 10.15, respectively. The pKL values that were used to correct pIC50 values obtained in buffer ACa at 4, 12 and 21°C are shown in Table 1 and were 9.66, 9.69 and 9.77, respectively.

Table 1.

Effect of temperature and assay buffer on the estimated pKL, nH and Bmax of [3H]clobenpropit in guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes

| Temperature (°C) |

Buffer A |

Buffer ACa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pKL | Bmax | nH | pKL | Bmax | nH | |

| 30 | 10.15±0.04 | 4.00±1.17 | 0.93±0.02 | ND | ND | ND |

| 21 | 10.40±0.08 | 3.80±0.97 | 1.08±0.09 | 9.77±0.20 | 3.28±0.65 | 1.20±0.05 |

| 12 | 10.38±0.07 | 4.06±0.55 | 0.90±0.03 | 9.69±0.18 | 4.02±0.83 | 1.05±0.09 |

| 4 | 10.57±0.03 | 4.00±0.48 | 1.11±0.06 | 9.66±0.27 | 4.04±0.68 | 1.13±0.12 |

Abbreviations: ND, not determined.

pKL, Bmax (fmol mg−1) and nH values were obtained by fitting saturation data to the Hill equation.

Data are the mean±s.e.m. of three experiments.

Calculation of thermodynamic parameters

The change in the standard Gibbs free energy (ΔG°) was calculated using the Gibbs–Helmholz thermodynamic equation (equation (2)).

where R is the ideal gas constant (8.31 J−1 mol−1 K), T is the temperature in degrees Kelvin and KA is the apparent association constant of the ligand at 294 K (1/KI).

Equation (2) is combined with the Gibbs free energy equation (3), to form the integrated van't Hoff equation (4).

where ΔS° is the entropy change of binding.

A plot, therefore, of ln KA versus 1/T allows the estimation of the enthalpy of binding (ΔH°) because the slope is −ΔH°/R. In addition, the entropy change (ΔS°) can be estimated as the y-intercept (−ΔS°/R) (see Borea et al., 1998). In these studies, ΔG°, ΔH° and ΔS° have been designated by their primed counterparts (ΔG°′, ΔH°′ and ΔS°′) because the studies were conducted at pH 7.4 (although it is common to see the primes omitted). This is because the terms ΔG°, ΔH° and ΔS°, only apply to measurements made under standard state conditions of 1 atmosphere and unit activity (sometimes stated as 1 M concentration) and at a 1 M hydrogen ion concentration (pH 0).

Statistical analysis

Differences in pKL and Bmax values of [3H]clobenpropit were determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc test or paired t-test. An F-test was used to establish whether saturation data was best fitted by the Hill equation or by the Hill equation with nH constrained to unity. The significance of differences in pKI values obtained at different temperatures, in replicate experiments, was determined by paired t-test. r2 values obtained from linear regression were used to determine whether there was a significant linear relationship between temperature (1/T) and ln KA values. An F-test was used to establish whether the slope was significantly different from zero. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Materials

[3H]clobenpropit (VUF9153) was prepared by Amersham International plc, (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) to a specific activity of 45 Ci mmol−1.

Proxyfan, chloroproxyfan, bromoproxyfan, iodoproxyfan, immepip and JB96132 were synthesised by James Black Foundation Chemists. 2-Methyl-1,2-di-3-pyridyl-1-propanone (metyrapone), HEPES (N-[2-hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulphonic acid]) and Trizma base were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., (Poole, Dorset, UK). R-α-MH, thioperamide and imetit were obtained from Research Biochemicals Inc., (Poole, Dorset, UK). All other materials were obtained from Fisher Scientific, Loughborough (Leicestershire, UK).

Results

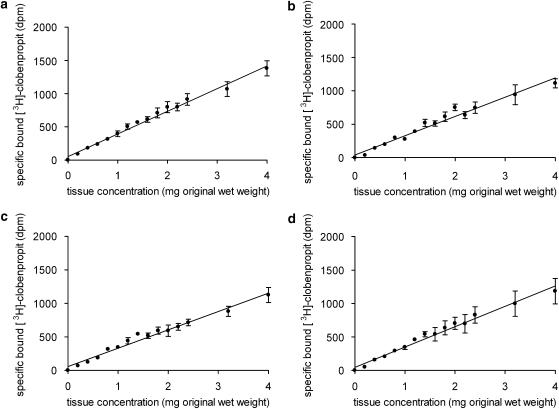

Effect of incubation temperature on the optimal tissue concentration

At 4, 12, 21 and 30°C (277, 285, 294 and 303 K), there was a linear relationship between the specific binding of 0.2 nM [3H]clobenpropit and membrane concentration up to 4 mg (see Figure 2). In buffer A, at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C, and a membrane concentration of 1.6 mg, 14.0±1.7; 13.1±1.3; 13.3±1.0 and 11.9±0.9% of the added [3H]clobenpropit was bound, respectively (n=3). There was no significant difference between the specific binding of [3H]clobenpropit as a percent of total binding (percentage specific binding) at each temperature in buffer A (4°C=41.5±3.4; 12°C=38.0±4.9; 21°C=38.8±5.0; 30°C=42.9±8.6%; n=3, ANOVA).

Figure 2.

Linearity of the relationship between specific binding of [3H]clobenpropit (0.2 nM) and added guinea-pig cerebral cortex membrane concentration at (a) 4°C, (b) 12°C, (c) 21°C and (d) 30°C. Increasing concentrations of guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes (0.2–4 mg) were incubated in triplicate with [3H]clobenpropit (0.2 nM) and buffer A in a final assay volume of 0.5 ml. The incubation was terminated after 2.75 h at 21 and 30°C and after 24 h at 4 and 12°C. Total binding was defined with buffer A and non-specific binding with 1 μM thioperamide. Data represent the mean±s.e.m. of three experiments. The line shown superimposed on the data was obtained by linear regression.

In buffer ACa, at 4, 12 and 21°C, and a membrane concentration of 1.6 mg, 5.2±0.8; 4.5±0.8 and 5.2±0.8% of the added 0.2 nM [3H]clobenpropit was bound, respectively (n=8). The percentage specific binding of [3H]clobenpropit at 21°C was significantly lower than that obtained at 4 and 12°C (4°C=77.9±2.6; 12°C=76.3±2.5 and 21°C=66.3±2.8%; n=4, P<0.05, ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test) and, at all temperatures, the non-specific binding was lower than that obtained in buffer A.

A membrane concentration of 1.6 mg was used for all subsequent experiments in both buffers.

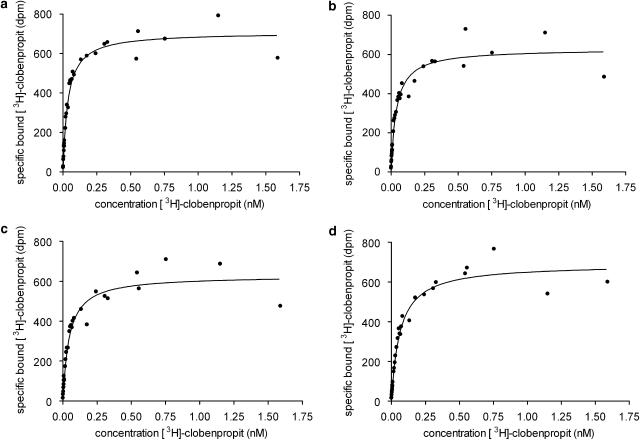

Effect of incubation temperature on [3H]clobenpropit saturation isotherms

In buffer A, the binding of [3H]clobenpropit was saturable at all temperatures (Figure 3). The mean Hill slope parameter estimates (nH), at the four temperatures, were not significantly different from unity (Table 1, t-test) and in each experiment, for each temperature, there was no significant difference between the fit to the Hill equation and the fit to the Hill equation with nH constrained to unity (P>0.05, F-test). The incubation temperature had no significant effect on the estimated histamine H3-receptor density (Bmax, Table 1, ANOVA).

Figure 3.

Saturation analysis of the binding of [3H]clobenpropit to guinea-pig cerebral cortex H3-receptors at (a) 4°C, (b) 12°C, (c) 21°C and (d) 30°C, in buffer A. Tissue (1.6 mg) was incubated in triplicate with increasing concentrations of [3H]clobenpropit (0.004–3 nM) in a final assay volume of 0.5 ml. Total and non-specific binding were defined with buffer A or 1 μM thioperamide, respectively. The incubation was terminated after 2.75 h at 21 and 30°C and after 24 h at 4 and 12°C. Data are representative of three experiments. The line shown superimposed through the data are the fit to the Hill equation.

In buffer ACa, at 30°C and over the concentration range of [3H]clobenpropit used (0.004–3 nM), the specific binding was lower and more variable than that obtained at 4, 12 and 21°C and, as a result, it was not possible to obtain accurate Bmax or pKL estimates. At 21, 12 and 4°C, the specific binding of [3H]clobenpropit was saturable (Figure 4), mean Hill slope parameter estimates (nH), were not significantly different from unity (Table 1, t-test) and in each experiment for each temperature, there was no significant difference between the fit to the Hill equation and the fit to the Hill equation with nH constrained to unity (P>0.05, F-test). The incubation temperature did not significantly change the estimated H3-receptor Bmax (Table 1, ANOVA).

Figure 4.

Saturation analysis of the binding of [3H]clobenpropit to guinea-pig cerebral cortex H3-receptors at (a) 4°C, (b) 12°C and (c) 21°C, in buffer ACa. Tissue (1.6 mg) was incubated in triplicate with increasing concentrations of [3H]clobenpropit (0.004–3 nM). Total and non-specific binding were defined with buffer ACa or 1 μM thioperamide, respectively. The incubation was terminated after 2.75 h at 21°C and after 24 h at 4 and 12°C. Data is representative of three experiments.

In buffer A, the pKL of [3H]clobenpropit increased significantly with decreasing incubation temperature (Table 1, ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc test, P<0.05;) and the pKL was significantly higher at 4°C than at 30°C (paired t-test, P<0.05). A van't Hoff plot of ln KA versus 1/T was linear with a positive slope which was significantly different from zero (F-test, P<0.05; Figure 5). In contrast, in buffer ACa, there was no relationship between assay incubation temperature and pKL, and there was no significant difference in the pKL of [3H]clobenpropit at the three temperatures (Table 1, paired t-test). The slope of the van't Hoff plot for [3H]clobenpropit, in buffer ACa, was not different from zero (F-test, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Van't Hoff plot showing the effect of temperature on the equilibrium association constants (KA) of [3H]clobenpropit in 20mM HEPES buffer (buffer A) and in buffer A with 300mM CaCl2 (buffer ACa). Data are the mean±s.e.m. of three replicate experiments. The lines shown superimposed through the data were obtained by linear regression.

Effect of incubation temperature on the association and dissociation rates of [3H]clobenpropit

In buffer A, the specific binding of 0.2 nM [3H]clobenpropit reached equilibrium after approximately 80, 30, 25 and 3 min incubations at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C, respectively (n=3, Figure 6). The [3H]clobenpropit association data obtained at all four temperatures could be fitted by a pseudo-first-order rate equation. The association rate constants (k+1) for the binding of [3H]clobenpropit to histamine H3-receptors on guinea-pig cortex membranes at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C are given in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Representative association–dissociation analysis of [3H]clobenpropit binding to H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes at (a) 4°C, (b) 12°C, (c) 21°C and (d)30°C. The association rate was determined under pseudo-first-order conditions because only ∼10% of the added [3H]clobenpropit was bound. [3H]clobenpropit (0.2 nM) was incubated, in a final assay volume of 0.5 ml for increasing times with membranes (1.6 mg at 4, 12, 21 or 30°C). Total and non-specific binding were defined with buffer A and 1 μM thioperamide, respectively. The dissociation rate for [3H]clobenpropit from H3-receptors was determined by incubating [3H]clobenpropit (0.2 nM) with membranes and buffer A and then adding 10 μl of 50 μM thioperamide (arrow). The bound radioligand was determined at increasing incubation times.

Table 2.

Effect of temperature on the association rate, dissociation rate and pKL of [3H]clobenpropit at histamine H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes

| Temperature (°C) | Temperature (K) | k+1 (M−1 min−1) | k−1 (min−1) | pKL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 303 | 77.26±5.29 × 108 | 3.32±0.50 × 10−1 | 10.37±0.10 |

| 21 | 294 | 7.49±1.32 × 108 | 0.44±0.06 × 10−1 | 10.27±0.27 |

| 12 | 285 | 10.60±0.84 × 108 | 0.33±0.05 × 10−1 | 10.60±0.12 |

| 4 | 277 | 6.37±3.3 × 108 | 0.047±0.001 × 10−1 | 11.01±0.20 |

Data are the mean±s.e.m. of three experiments.

The dissociation data for [3H]clobenpropit could also be fitted by a first-order rate equation. The dissociation rate constants (k−1) at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C are shown in Table 2, along with the calculated pKL values; the latter increased with decreasing temperature (Table 2). These pKL values were not significantly different from those obtained using saturation analysis at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C (compare pKL values in Tables 1 and 2, t-test).

Effect of incubation temperature on ligand pKI values in buffer A and buffer ACa

In both buffer A and buffer ACa, each histamine H3-receptor ligand produced a concentration-dependent inhibition of the specific binding of [3H]clobenpropit to H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes at all temperatures, as illustrated in Figure 7 for R-α-MH and thioperamide. In buffer A, the mean mid-point slope parameter estimates (nH) for all the agonists, except proxyfan and imetit (see Table 3), at most incubation temperatures were significantly less than unity (t-test, P<0.05). The mean mid-point slope parameter estimate for thioperamide was significantly less than unity at 21 and 4°C (Table 3, t-test, P<0.05).

Figure 7.

Competition curves for an H3-receptor agonist, R-α-MH, and antagonist, thioperamide, at sites labelled with 0.2 nM [3H]clobenpropit in guinea-pig cerebral cortex. (a–c) Mean % specific binding of R-α-MH and thioperamide at 4°C, 12 and 21°C in buffer A and buffer ACa (d) mean % specific binding of R-α-MH and thioperamide at 30°C in buffer A. Guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes (1.6 mg) were incubated in a final volume of 0.5 ml with HEPES–NaOH buffer, [3H]clobenpropit (0.2 nM) and increasing concentrations of ligands for 2.75 h at 30 and 21°C and for 24 h at 12 and 4°C. Total and non-specific binding of [3H]clobenpropit were defined using appropriate buffer and 1 μM thioperamide, respectively. Data are the mean±s.e.m. of between five and six experiments (see Table 3). The lines shown superimposed on the data were obtained using the fit to the Hill equation.

Table 3.

pKI and nH values for histamine H3-receptor agonists and antagonists at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C (277, 285, 294 and 300 K)

| Ligand | Temperature (K) |

Buffer A |

Buffer ACa |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pKI or pKI′ | nH | n | pKI or pKI′ | nH | n | ||

| Histamine H3-receptor agonists | |||||||

| proxyfan | 303 | 8.51±0.13 | 0.97±0.21 | 3 | ND | ND | |

| 294 | 8.61±0.17 | 0.73±0.06 | ND | ND | |||

| 285 | 8.05±0.08 | 0.89±0.06 | ND | ND | |||

| 277 | 7.89±0.07 | 1.07±0.12 | ND | ND | |||

| chloroproxyfan | 303 | 9.04±0.15 | 0.81±0.04a | 5 | ND | ND | 4 |

| 294 | 9.00±0.22 | 0.77±0.04a | 7.76±0.12 | 1.04±0.05 | |||

| 285 | 8.78±0.14 | 0.71±0.07a | 7.68±0.14 | 0.88±0.04 | |||

| 277 | 8.66±0.10 | 0.90±0.12 | 7.82±0.20 | 0.94±0.07 | |||

| bromoproxyfan | 303 | 9.32±0.05 | 0.77±0.07a | 3 | ND | ND | 4 |

| 294 | 9.28±0.02 | 0.83±0.09 | 8.13±0.26 | 0.99±0.04 | |||

| 285 | 9.04±0.14 | 0.81±0.04a | 8.04±0.30 | 0.91±0.06 | |||

| 277 | 9.13±0.15 | 0.88±0.16 | 8.16±0.29 | 0.95±0.08 | |||

| iodoproxyfan | 303 | 9.82±0.07 | 0.65±0.10a | 4 | ND | ND | 4 |

| 294 | 9.79±0.05 | 0.67±0.03a | 8.10±0.36 | 0.94±0.08 | |||

| 285 | 9.45±0.10 | 0.62±0.08a | 8.26±0.26 | 0.88±0.02 | |||

| 277 | 9.27±0.08 | 0.94±0.16 | 8.31±0.31 | 0.91±0.03 | |||

| imetit | 303 | 9.17±0.19 | 0.76±0.09 | 4 | ND | ND | 6 |

| 294 | 9.33±0.12 | 0.80±0.12 | 7.93±0.17 | 0.86±0.05 | |||

| 285 | 9.03±0.07 | 0.85±0.08 | 7.87±0.12 | 0.89±0.05 | |||

| 277 | 9.16±0.12 | 0.87±0.08 | 7.89±0.14 | 0.94±0.07 | |||

| R-α-MH | 303 | 9.13±0.22 | 0.63±0.06a | 5 | ND | ND | 5 |

| 294 | 9.15±0.18 | 0.63±0.02a | 7.30±0.14 | 0.83±0.07 | |||

| 285 | 8.89±0.21 | 0.66±0.05a | 7.09±0.20 | 0.81±0.05a | |||

| 277 | 8.87±0.22 | 0.62±0.03a | 7.21±0.22 | 0.86±0.04 | |||

| immepip | 303 | 9.47±0.03 | 0.71±0.06a | 5 | ND | ND | 5 |

| 294 | 9.53±0.04 | 0.88±0.05 | 8.07±0.11 | 0.86±0.05 | |||

| 285 | 9.39±0.13 | 0.82±0.05a | 7.91±0.12 | 0.91±0.03a | |||

| 277 | 9.34±0.14 | 0.73±0.03a | 7.99±0.19 | 0.90±0.02a | |||

| Histamine H3-receptor antagonists | |||||||

| JB96132 | 303 | 8.95±0.07 | 1.08±0.14 | 3 | ND | ND | 4 |

| 294 | 9.17±0.13 | 0.99±0.06 | 8.97±0.14 | 1.06±0.12 | |||

| 285 | 9.11±0.09 | 0.85±0.05 | 8.82±0.17 | 0.95±0.04 | |||

| 277 | 9.49±0.05 | 0.97±0.09 | 9.20±0.24 | 0.94±0.03 | |||

| thioperamide | 303 | 8.35±0.06 | 0.90±0.08 | 6 | ND | ND | 5 |

| 294 | 8.50±0.05 | 0.82±0.04a | 9.00±0.15 | 0.96±0.11 | |||

| 285 | 8.66±0.09 | 0.96±0.06 | 8.84±0.12 | 0.88±0.05 | |||

| 277 | 8.75±0.02 | 0.81±0.04a | 9.00±0.13 | 0.86±0.03a | |||

Abbreviation: ND, not determined.

Data are the mean±s.e.m. pKI′ is the ligand affinity when nH is significantly less than unity.

nH significantly different from unity, P<0.05 t-test.

In buffer ACa, the mean nH parameter estimates for the agonists were not significantly different from unity with the exception of iodoproxyfan and R-α-MH at 12°C and immepip at 4 and 12°C. The mean nH value for thioperamide was significantly less than unity at 4°C (t-test, P<0.05).

Notwithstanding the finding of nH values that were significantly less than unity, dissociation constants were subsequently determined from pIC50 values using the Cheng and Prusoff (1973) equation to correct for the different receptor occupancy of [3H]clobenpropit in the different buffers at the different temperatures. The parameter pKI′ has been assigned to dissociation constants which were derived from pIC50 values, where mean nH parameter estimates were significantly less than unity. The pKL values that were used to correct pIC50 values obtained in buffer A and buffer ACa are presented in Table 1.

The effect of temperature on pKI or pKI′ values of all ligands in buffer A and buffer ACa are listed in Table 3. In buffer A, the pKI values of the two antagonist ligands, thioperamide and JB96132 were significantly higher at 4°C than at 30°C (P<0.05, paired t-test). The pKI′ values for the H3-receptor agonists, proxyfan, chloroproxyfan, iodoproxyfan and R-α-MH were significantly lower at 4°C than at 30°C (P<0.05, paired t-test) and there was no significant difference between pKI′ values obtained for immepip, imetit and bromoproxyfan at these temperatures (paired t-test). In buffer ACa, there was no significant difference between pKI values at 4 and 21°C for all ligands (Table 3, paired t-test).

Thermodynamic parameters of ligand binding

Van't Hoff plots of ln KA versus 1/T were constructed for all ligands using the affinity values (1/KI) obtained in buffer A (4, 12, 21 and 30°C) and buffer ACa (4, 12, 21°C) (see, for e.g., Figures 8 and 9). The van't Hoff plots, constructed for thioperamide and JB96132, using pKI values obtained in buffer A, had positive slopes which were significantly different from zero (Figure 8, F-test, P<0.05). The van't Hoff plots, constructed for proxyfan, chloroproxyfan and iodoproxyfan using pKI values obtained in buffer A, had negative slopes which were significantly different from zero (F-test, P<0.05). The van't Hoff plots, constructed for all ligands using pKI values obtained in buffer ACa, had slopes which were not significantly different from zero (F-test, P<0.05).

Figure 8.

Van't Hoff plots showing the effect of temperature on the equilibrium association constants (KA) of (a) thioperamide and (b) JB96132 in buffer A and buffer ACa. Data are the mean±s.e.m. of between three and six replicate experiments. The lines shown superimposed through the data were obtained by linear regression.

Figure 9.

Van't Hoff plots showing the effect of temperature on the equilibrium association constants (KA) of (a) iodoproxyfan and (b) chloroproxyfan in buffers A and ACa. Data are the mean±s.e.m. of between four and five replicate experiments. The lines shown superimposed through the data were obtained by linear regression.

Mean values of enthalpy (ΔH°′), entropy (ΔS°′), −TΔS°′ and the Gibb's free energy (ΔG°′) of ligands in buffer A and ACa, were obtained from van't Hoff plots and are presented in Tables 4 and 5. ΔG°′ was also calculated at 21°C (294 K) using the Gibbs–Helmholz equation.

Table 4.

Thermodynamic parameters of binding to histamine H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes in buffer A

| Ligand | Intrinsic activity (α) | ΔGo′ calculated (kJ mol−1)a | ΔGo′ (kJ mol−1) | ΔHo′ (kJ mol−1) | −TΔSo′ (kJ mol−1) | ΔSo′ (J mol−1 K−1) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine H3-receptor agonists | |||||||

| immepip | 1.00b | −53.8±0.3 | −53.4±0.2 | 9.1±10.0 | −62.5±9.9 | 211.7±33.3 | 5 |

| imetit | 0.90b,c | −52.6±0.7 | −51.9±0.8 | 6.4±6.2 | −58.3±6.9 | 197.8±23.3 | 4 |

| R-α-MH | 1.00c | −51.6±1.0 | −51.2±1.1 | 19.1±3.9 | −70.3±4.0 | 218.3±14.2 | 5 |

| proxyfan | 0.35c | −48.6±1.0 | −47.4±0.7 | 44.5±9.2 | −91.8±9.8 | 311.3±33.1 | 3 |

| chloroproxyfan | 0.45c | −46.9±2.9 | −50.5±0.9 | 26.6±4.9 | −77.1±5.8 | 261.4±19.7 | 5 |

| bromoproxyfan | 0.69c | −51.6±0.9 | −52.2±0.2 | 14.2±13.4 | −66.3±13.3 | 224.9±45.0 | 3 |

| iodoproxyfan | 0.90c | −55.3±0.3 | −54.7±0.3 | 37.3±7.3 | −92.0±7.3 | 311.0±24.4 | 4 |

| Histamine H3-receptor antagonists | |||||||

| JB96132 | 0c | −51.8±0.7 | −51.0±0.5 | −34.1±6.5 | −16.9±6.8 | 57.3±23.2 | 3 |

| thioperamide | 0c | −47.8±0.3 | −48.0±0.3 | −30.5±6.1 | −17.5±6.1 | 59.3±20.6 | 6 |

| [3H]clobenpropit | 0c | −58.5±0.4 | −58.0±0.3 | −22.9±1.2 | −35.1±1.3 | 119.5±4.4 | 3 |

Data are the mean±s.e.m.

ΔGo′ at 21°C, calculated using equation 2.

a values from Alves-Rodrigues et al., 2001

Intrinsic activity in guinea-pig ileum bioassay, see Harper et al. (2007).

Table 5.

Thermodynamic parameters of binding to histamine H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes in buffer ACa

| Ligand | ΔGo′ calc (kJ mol−1)a | ΔGo′ (kJ mol−1) | ΔHo′ (kJ mol−1) | −TΔSo′ (kJ mol−1) | ΔSo′ (J mol−1 K−1) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine H3-receptor agonists | ||||||

| immepip | −45.6±0.6 | −45.6±0.7 | 15.1±3.4 | −60.7±3.3 | 205.7±11.3 | 5 |

| imetit | −44.8±1.0 | −44.7±0.8 | 3.4±11.1 | −50.0±9.6 | 169.6±32.6 | 6 |

| R-α-MH | −39.2±2.2 | −40.9±0.7 | −9.2±17.6 | −50.2±17.6 | 170.0±59.9 | 5 |

| chloroproxyfan | −45.1±1.5 | −43.7±0.7 | −3.3±8.9 | −38.1±10.4 | 136.8±28.7 | 4 |

| bromoproxyfan | −45.9±1.4 | −45.7±1.5 | −2.8±6.6 | −42.9±6.1 | 145.5±20.8 | 4 |

| iodoproxyfan | −47.1±1.5 | −47.2±1.6 | −4.7±4.2 | −51.8±3.9 | 175.5±13.1 | 4 |

| Histamine H3-receptor antagonists | ||||||

| JB96132 | −50.6±0.8 | −50.1±0.8 | −20.9±9.4 | −29.3±8.8 | 99.1±29.9 | 4 |

| thioperamide | −50.1±0.8 | −51.3±0.8 | −40.7±6.4 | −10.3±6.8 | 137.9±21.8 | 5 |

| [3H]clobenpropit | −54.4±1.5 | −54.6±1.1 | −10.5±8.5 | −43.8±9.7 | 149.0±32.9 | 3 |

Data are the mean±s.e.mean.

ΔGo′ at 21°C, calculated using equation 2.

In buffer A, the mean ΔH°′ values for JB96132, thioperamide and [3H]clobenpropit were negative (Table 4) and mean ΔS°′ values were positive (Table 4). The mean ΔH°′ and ΔS°′ values for the ligands classified as agonists in the guinea-pig ileum longitudinal muscle myenteric plexus (see Harper et al., 2007) were also positive (Table 4).

In buffer ACa, the mean ΔH°′ values for the antagonists were all negative, over a fourfold range, while the mean ΔS°′ values were positive (Table 5) The mean ΔH°′ values for the agonist ligands, with the exception of immepip and imetit, were also negative (Table 5) and the mean ΔS°′ values for the agonists in buffer ACa were positive (Table 5).

Extrathermodynamic plots

A plot of the ΔH°′ and –TΔS°′ for all ligands, obtained in buffer A and shown in Table 3, indicated that the binding of the antagonists was enthalpy- and entropy-driven (Figure 10a). In contrast, the extrathermodynamic plot indicated that the agonist binding was driven by an increase in entropy. There was a significant linear relationship between the two parameters (r=0.99, P<0.01, slope=0.98±0.03, y-intercept=−51.9, x-intercept=−52.8; Figure 10a).

Figure 10.

An extrathermodynamic plot for agonist and antagonist ligands in (a) buffer A and (b) buffer ACa. The lines shown superimposed through the data were obtained by linear regression.

The extrathermodynamic plot of ΔH°′ versus −TΔS°′ for all ligands, obtained in buffer ACa, indicated that the binding of all ligands, except imetit and immepip, was enthalpy- and entropy-driven (Figure 10b). There was a significant linear relationship between ΔH°′ and –TΔS°′ (r=0.99, P<0.01, slope=0.88±0.13, y-intercept=−53.9, x-intercept=49.5; Figure 10b).

Discussion

In this study, we have determined the thermodynamic parameters underlying the binding of 10 ligands (seven agonists and three antagonists) at histamine H3-receptors of guinea-pig cortex. In previous studies, we have shown that agonist affinity values are overestimated in H3-receptor radioligand-binding assays, when buffer does not contain salts, and that the degree of affinity overestimation is correlated with the ligand's intrinsic activity (α) (see Harper et al., 2007). In addition, we have shown that when H3-receptor radioligand-binding assays are conducted in the presence of salts, pKI estimates are closer to pKapp values estimated by the method of Furchgott in the guinea-pig ileum bioassay (see Harper et al., 2007). Therefore, to establish whether the thermodynamic parameters underlying the binding of agonists is dependent on whether agonist pKI values are equivalent to pKapp values, we have determined agonist pKI values in the presence and absence of buffer salts (buffer ACa and buffer A).

Both kinetic studies and saturation studies of [3H]clobenpropit binding were performed at each assay temperature, in order to satisfy criteria which should be met when performing thermodynamic analysis of ligand binding, that is, that the binding should be to a homogeneous receptor population and that the binding of radioligand and ligand should reach equilibrium at each temperature. Saturation analysis was also performed at each temperature so that pIC50 values obtained in competition assays could be corrected for by any change in the occupancy of [3H]clobenpropit resulting from temperature-dependence of the pKL. Saturation analysis confirmed that [3H]clobenpropit labelled a homogeneous population of H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex in both the presence (buffer ACa) and absence of buffer salt (300 mM CaCl2) (buffer A; Figures 2 and 3). Thus, at all incubation temperatures, the mean nH parameter estimate was not significantly different from unity and the H3-receptor density (Bmax) was not significantly changed (Figure 2, 3 and Table 1). Kinetic studies confirmed that the incubation time used for the saturation analysis (4 and 12°C=24 h; 21 and 30°C=2.75 h; Figure 5) was sufficient for equilibrium binding of the radioligand to have been achieved (3, 25, 30 and 80 min at 30, 21, 12 and 4°C) so that the pKL values estimated at each temperature were correct. The dissociation rate (t1/2) of [3H]clobenpropit, determined in the kinetic studies at each temperature, indicated that the incubation times of 2.75 h at 21 and 30°C and of 24 h at 4 and 12oC, used for competition studies, were sufficient for equilibrium binding of agonist and antagonist ligands and thus for the accurate determination of pIC50 values. This was because in each case the incubation time was in excess of five times the t1/2 (Figure 6; see Motulsky and Mahan, 1983).

In the competition studies performed in buffer A, the finding that mean nH parameter estimates for some of the agonist ligands at 21°C were significantly less than unity was consistent with our previous studies (Harper et al., 2007). This agonist behaviour at 21°C and also that detected for some agonists at 4, 12 and 30°C, can be explained by the extended ternary complex or cubic ternary complex model (TCM) (Samama et al., 1993; Lefkowitz et al., 1993; Weiss et al., 1996). In the extended TCM, it is proposed that the receptor can exist in a low-affinity state (R) and a high-affinity state (R*) which can also interact with a G-protein (R*G) in the absence of the agonist. Thus, flat competition curves are observed because the agonist binds with high affinity to R* or R*G and with lower affinity to R. In the cubic TCM, it is postulated that the receptor can exist in a low-affinity state (Ri equivalent to R in the TCM) and a high-affinity state (Ra, equivalent to R* in the TCM) and that both R and R* can exist as high-affinity states as a consequence of interaction with a G-protein (RG and R*G). Therefore, according to this model, it is possible to obtain flat competition curves because the agonist binds with low affinity to R and with high affinity to preformed high-affinity receptor states (R* and R*G). However, flat competition curves could also arise because the agonist induces varying amounts of receptor to form a high-affinity state (AR*G or ARG) through binding to low-affinity receptors (R).

The finding of mean nH values significantly less than unity for the antagonist thioperamide at 4 and 21°C in buffer A and at 4°C in buffer ACa, may be a result of type 1 error. This is because at 21°C, at least, this contrasts with our previous studies where we found that nH was not different from unity (Harper et al., 2007). In addition, we found that there was no significant difference between the fit of individual replicate thioperamide competition curves, obtained at 4 and 21°C, to the Hill equation and to the Hill equation with nH constrained to unity, as judged by an F-test. Type 1 error could also explain the finding of nH values significantly less than unity for iodoproxyfan and R-α-MH at 12°C and immepip at 4 and 12°C, under assay conditions (buffer-containing salts, buffer ACa) which we have previously suggested, provide a measure of the agonist pKapp (Harper et al., 2007) and therefore under conditions where we would expect nH not to be different from unity. In support of this, when the mean agonist nH values were significantly less than unity, there was no significant difference between the fit of the individual replicate competition curves to the Hill equation and to the Hill equation with nH constrained to unity, as judged by an F-test.

In light of the finding of nH values which were significantly less than unity for some ligands at some of the temperatures, it could be argued that we should not have derived pKI values from pIC50 values using the Cheng–Prusoff equation. This is because the derivation of this correction relies on simple competition between two ligands at a homogenous receptor population and, therefore, should be applied only when nH is not different from unity. However, in this study, we have corrected all pIC50 values using the Cheng–Prusoff equation to correct for the differential occupancy of ∼0.2 nM [3H]clobenpropit in the two buffers (buffer A and buffer ACa) at the different incubation temperatures. Ideally, for this not to be a confounding problem, we would have performed competition studies in both buffers at each temperature at [3H]clobenpropit concentrations equivalent to the KL. However, this was not possible because the low specific activity of the radioligand resulted in too small a specific binding window in buffer A at the ligand concentration ideally required for studies at 4°C (∼0.03 nM).

It could also be reasoned that the data could have been analysed using a two-site model and then the pIC50 values corrected using the Cheng–Prusoff equation to provide pKH and pKL parameters. However, we chose not to analyse the data in this way because it would not have been possible to obtain these parameters for all the agonists at all the temperatures. This is because for some agonists at some temperatures, the mean nH value was not different from unity and for individual replicate competition data, the fit to the Hill equation was not significantly different to the fit to the Hill equation with nH constrained to unity (e.g. proxyfan at 4, 12, 21 and 30°C; bromoproxyfan at 4 and 21°C, Table 3).

It is noteworthy that the affinity values obtained for all the ligands in buffer A at 21°C were consistent with observations made in a previous study using the same assay buffer and incubation temperature, as was the pKI value for R-α-MH at 21°C in buffer ACa (Harper et al., 2007). In addition, it is notable that the pKI values for all the agonists, at 21°C in buffer ACa, were associated with nH values that were not different from unity and, moreover, that were not different from agonist pKapp values estimated previously in the guinea-pig ileum (see Harper et al., 2007).

The discovery of thermodynamic discrimination of agonists and antagonists, at the H3-receptor (Figure 10a, antagonist binding=ΔH°′ and ΔS°′-driven; agonist binding=ΔS°′-driven) mirrors that reported for binding of agonist and antagonist ligands to the adenosine A1 receptor (Dalpiaz et al., 2000), adenosine A2A receptor (Borea et al., 1996b), GABAA receptor (Maksay, 1994) and serotonin 5-HT3 receptor (Borea et al., 1996a). The finding that the binding of all the H3-receptor ligands, investigated in this study was, at least in part, entropy driven could be explained by disorganisation of a solvation sphere around the ligands as they bind to the receptor; this is because all the ligands contain an imidazole moiety and this would be protonated at the assay pH of 7.4. It would have been interesting to determine whether the binding of some of the recently described non-imidazole histamine H3-receptor antagonists (e.g. Linney et al., 2000; Lazewska et al., 2002; Meier et al., 2002; Shah et al., 2002; Apodaca et al., 2003; Chai et al., 2003; Miko et al., 2003, 2004; Turner et al., 2003; Zaragoza et al., 2004, 2005; Sun et al., 2005; Lazewska et al., 2006; Rivara et al., 2006) are also, in part, entropy driven.

It has been suggested for the ligand-gated ion channels, where the thermodynamic discrimination of agonists and antagonists mirrors that of the H3-receptor, that this phenomenon can be explained by both interaction of the ligand with the receptor and variation in the water-accessible surface which occurs when the agonist induces channel opening (Borea et al., 1998). Therefore, a possible explanation for the thermodynamic discrimination of H3-receptor agonists and antagonists is that the agonists induce a change in receptor conformation, perhaps into a less-constrained state, which in turn, leads to the formation of a ternary complex with a G-protein and this consequently results in a decrease in the solvation of the cytosolic side of the receptor. The finding of a decrease in enthalpy associated with antagonist binding may be explained by hydrogen bond formation and van der Waals interactions occurring between the ligands and the binding pocket which cannot be compensated for by changes in entropy that result from agonist-induced conformational changes in the receptor.

The hypothesis that agonist binding at H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex induces ternary complex formation (ARG or AR*G) and this brings about the large increase in entropy, is supported by the finding that under conditions (buffer ACa) where the agonists express pKI values that are closely correlated with their pKapp values (see Harper et al., 2007), agonist and antagonists cannot be discriminated thermodynamically (Figure 10b). Thus, in buffer ACa, the agonist pKI values remained unchanged with decreasing temperature in the same manner as the antagonist ligands (Table 3). In addition, van't Hoff plots constructed from agonist thermodynamic data obtained in buffer ACa (Figure 9), are similar to those of the antagonists [3H]clobenpropit (Figure 5), thioperamide and JB96132 (Figure 8).

Despite the gross thermodynamic discrimination between the agonist and antagonist ligands at H3-receptors (Figure 10a), it was surprising that there was no relationship between agonist intrinsic activity (α), measured previously in a guinea-pig ileum bioassay (see Harper et al., 2007) and either mean ΔH°′ or mean ΔS°′ (see Table 4; e.g. R-α-MH, ΔH°′=19.1, ΔS°′=218.3, α=1.0; proxyfan, ΔH°′=44.5, ΔS°′=311.3, α=0.35) even for the analogues of proxyfan which differ only in the halogen substitution at the para position of the benzene ring (Figure 1) (Table 4; proxyfan ΔS°′=311.3, ΔH°′=44.5, α=0.35; iodoproxyfan ΔS°′=311.0, ΔH°′=37.3, α=0.90). Failure to find a relationship between intrinsic activity and thermodynamic parameters may have been a consequence of the experimental design. This is because we have previously found a significant effect of tissue preparation on the agonist pKI′ values under conditions where this parameter is not equivalent to the pKapp (see Harper et al., 2007). Ideally, we would have generated competition curve data for all the ligands at each temperature on the same experimental day, however, this was not possible due to restrictions in the availability of equipment required to accurately maintain temperatures of 4, 12, 21 and 30°C.

It is perplexing that the entropy associated with the binding of antagonists is increased in the presence of buffer salts (buffer ACa) despite an overall decrease in the entropy of agonist binding (Tables 4 and 5; e.g. clobenpropit buffer A ΔS°′=119.5; buffer ACa, ΔS°′=149.0; iodoproxyfan buffer A ΔS°′=311.0, buffer ACa, ΔS°′=175.5). This may be a consequence of the buffer salts increasing the hydration of the ligands so that it is necessary for more water to be stripped away upon receptor binding. This possibility may explain why although the overall entropy associated with agonist binding is reduced in the presence of salts and in conditions where the agonist affinity is similar to pKapp, it is not as low as that of antagonist binding in the absence of buffer salts (buffer A). It would be interesting to repeat these thermodynamic studies to establish whether agonist ΔS°′ values are lower when G-protein coupling of the H3-receptor is prevented, perhaps by Pertussis toxin treatment, but where there is not the potential complication of changes in ligand hydration.

The linear relationship between mean ΔH°′ and TΔS°′ for the H3-receptor was not unexpected and has been reported for numerous G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ligand-gated ion channels (e.g. β-adrenoceptor, adenosine A1, adenosine A2A, dopamine D2, serotonin 5-HT1A, glycine, GABAA, and nicotinic receptor; see Borea et al., 1998). The linear relationship indicates that enthalpy–entropy compensation exists for the H3-receptor, that is, changes in enthalpy are compensated for by changes in entropy (or vice versa) such that the free-energy change ΔG°′ is constant.

Conclusion

The binding of agonists and antagonists at the histamine H3-receptor can be thermodynamically discriminated when agonist pKI values are not equivalent to pKapp values; agonist binding is entropy-driven and antagonist binding enthalpy- and entropy-driven. In the presence of buffer salts, where the ligand pKI values are more closely correlated with their pKapp values estimated in a functional bioassay, the thermodynamic parameters underlying agonist binding are changed and are not different from those of antagonists.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by Johnson and Johnson.

Abbreviations

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- R-α-MH

R-α-methylhistamine

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Alves-Rodrigues A, Lemstra S, Vollinga RC, Menge WMPB, Timmerman H, Leurs R. Pharmacological analysis of immepip and imetit homologues. Further evidence for histamine H3 receptor heterogeneity. Behav Brain Res. 2001;124:121–127. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca R, Dvorak CA, Xiao W, Barbier AJ, Boggs JD, Wilson SJ, et al. A new class of diamine-based human histamine H3 receptor antagonists: 4-(aminoalkyloxy)benzylamines. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3938–3944. doi: 10.1021/jm030185v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronstam RS, Narayanan TK. Temperature effect on the detection of muscarinic receptor-G protein interactions in ligand binding assays. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:1045–1049. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borea PA, Dalpiaz A, Gessi S, Gilli G. Thermodynamics of 5-HT3 receptor binding discriminates agonistic from antagonistic behaviour. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996a;298:329–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00813-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borea PA, Dalpiaz A, Varani K, Gessi S, Gilli G. Binding thermodynamics at A1 and A2A adenosine receptors. Life Sci. 1996b;59:1373–1388. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(96)00311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borea PA, Varani K, Gessi S, Gilli P, Gilli G. Binding thermodynamics at the human neuronal nicotine receptor. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)00578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai W, Breitenbucher JG, Kwok A, Li X, Wong V, Carruthers NI, et al. Non-imidazole heterocyclic histamine H3-receptor antagonists. Bioorgan Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1767–1770. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YC, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant Ki and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50% inhibition IC50 of an enzymic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalpiaz A, Borea PA, Gessi S, Gilli G. Binding thermodynamics of 5-HT1A receptor ligands. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;312:107–114. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00429-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalpiaz A, Scatturin A, Varani K, Pecoraro R, Pavan B, Borea PA. Binding thermodynamics and intrinsic activity of adenosine A1 receptor ligands. Life Sci. 2000;67:1517–1524. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte EP, Oliveira CR, Caravalho A. Thermodynamic analysis of antagonist and agonist interactions with dopamine receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;147:227–239. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90781-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper EA, Gardner B, Shankley NP, Black JW. Histamine H3-receptor agonists and antagonists can be thermodynamically-discriminated. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;186P doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper EA, Shankley NP, Black JW. Evidence that histamine homologues discriminate between H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex and ileum longitudinal muscle myenteric plexus. Br J Pharmacol. 1999a;128:751–759. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper EA, Shankley NP, Black JW. Characterisation of the binding of [3H]-clobenpropit to histamine H3-receptors in guinea-pig cerebral cortex membranes. Br J Pharmacol. 1999b;128:881–890. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper EA, Shankley NP, Black JW.Correlation of apparent affinity values obtained in a H3-receptor binding assay with apparent affinity (pKapp) and intrinsic activity (α) estimated in functional bioassay Br J Pharmacol 2007 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707174E-pub ahead of print: 12 March 2007; doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hitzeman R. Thermodynamic aspects of drug–receptor interactions. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1988;9:408. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(88)90068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick GJ, Tayar NEL, Van De Waterbeemb H, Testa JB, Marsden CD. The thermodynamics of agonist and antagonist binding to dopamine D-2 receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 1986;30:226–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazewska D, Kiec-Kononowicz K, Pertz HH, Elz S, Stark H, Schunack W. Piperidine-containing histamine H3 receptor antagonists of the carbamate series: the influence of the additional ether functionality. Pharmazie. 2002;57:791–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazewska D, Ligneau X, Schwartz J-C, Schunack W, Stark H, Kiec-Kononowicz K. Ether derivatives of 3-piperidinopropanol-1-ol as non-imidazole histamine H3 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;14:3522–3529. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz RJ, Cotecchia S, Samama P, Costa T. Constitutive activity of receptors coupled to guanine nucleotide regulatory proteins. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:303–307. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90048-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J-G, Raffa RB, Cheung P, Tzeng T-B, Liu-Chen L-Y. Apparent thermodynamic parameters of ligand binding to the cloned rat μ-opioid receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;354:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linney ID, Buck IM, Harper EA, Kalindjian SB, Pether MJ, Shankley NP, et al. Design, synthesis and structure–activity relationships of novel non-imidazole histamine H3 receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2362–2370. doi: 10.1021/jm990952j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire PA, Loew GH. Thermodynamics of ligand binding to the cloned δ-opioid receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;318:505–509. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00894-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maksay G. Thermodynamics of γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor binding differentiate agonists from antagonists. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:386–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier G, Ligneau X, Pertz HH, Ganellin CR, Schwartz J-C, Schunack W, et al. Piperidino-hydrocarbon compounds as novel non-imidazole histamine H3-receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;10:2535–2542. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miko T, Ligneau X, Pertz HH, Arrang J-M, Ganellin CR, Schwartz J-C, et al. Structural variations of 1-(4-(phenoxymethyl)benzyl) piperidines as non-imidazole histamine H3 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:2727–2736. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miko T, Ligneau X, Pertz HH, Ganellin R, Arrang J-M, Schwartz J-C, et al. Novel non-imidazole histamine H3-receptor antagonists: 1-(4-(phenoxymethyl)benzyl)piperidines and related compounds. J Med Chem. 2003;46:1523–1530. doi: 10.1021/jm021084k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H, Richards JG. Agonist and antagonist benzodiazepine receptor interaction in vitro. Nature. 1981;24:763–765. doi: 10.1038/294763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky HJ, Mahan LC. The kinetics of competitive radioligand binding predicted by the law of mass action. Mol Pharmacol. 1983;25:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffa RB, Porreca F. Thermodynamic analysis of the drug–receptor interactions. Life Sci. 1989;44:245. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90182-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith MAE, Sershen H, Lajtha A. Thermodynamics of the interaction of tricyclic drugs with binding sites for 3H-imipramine in mouse cerebral cortex. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:4101–4104. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara M, Zuliani V, Cocconelli G, Morini G, Comini M, Rivara S, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new non-imidazole H3-receptor antagonists of the 2-aminobenzimidazole series. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;14:1413–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samama P, Cotecchia S, Costa T, Lefkowitz RJ. A mutation-induced activated state of the β2-adrenergic receptor. Extending the ternary complex model. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4625–4636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah C, McAtee L, Breitenbucher JG, Rudolph D, Li X, Lovenberg TW, et al. Novel human histamine H3 receptor antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:3309–3312. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00738-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Zhao C, Gfesser GA, Thifaoult C, Miller TR, March K, et al. Synthesis and SAR of 5-amino- and 5-(aminoethyl)benzofuran histamine H3 receptor antagonists with improved potency. J Med Chem. 2005;48:6482–6490. doi: 10.1021/jm0504398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa B, Jenner P, Kilpatrick GJ, Eltayar N, Van De Waterbeemb H, Marsden CD. Do thermodynamic studies provide information about both binding to and the activation of dopaminergic and other receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36:4041–4046. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd RD, Babinski J. A thermodynamic study of 5-[3H]hydroxytryptamine binding to human cortex membranes. J Neurochem. 1987;49:1480–1483. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner SC, Esbenshade TA, Bennani YL, Hancock AA. A new class of histamine H3-receptor antagonists: synthesis and structure-activity relationships of 7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-6H-cyclohepta[b]-quinolines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;12:2131–2135. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiland GA, Minneman KP, Molinoff PB. Fundamental difference between the molecular interactions of agonists and antagonists with the β-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1979;281:114. doi: 10.1038/281114a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JM, Morgan PH, Lutz MW, Kenakin TP. The cubic ternary complex receptor–occupancy model I. Model Description. J Theor Biol. 1996;178:151–167. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahniser NR, Molinoff PB. Thermodynamic differences between agonist and antagonist interaction with binding sites for 3H-spiroperidol in rat striatum. Mol Pharmacol. 1983;23:303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza F, Stephensen H, Knudsen SM, Pridal L, Wulff BS, Rimvall K. 1-alkyl-4-acylpiperazines as a new class of imidazole-free histamine H3 receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2822–2838. doi: 10.1021/jm031028z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaragoza F, Stephensen H, Peschke B, Rimvall K. 2-(4-alkylpiperazin-1-yl)quinolines as a new class of imidazole-free histamine H3-receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 2005;48:306–311. doi: 10.1021/jm040873u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]