Abstract

Background and purpose:

For development of mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) models, continuous recording of drug effects is essential. We therefore explored the use of isoprenaline in the continuous measurement of the cardiovascular effects of antagonists of β-adrenoceptors (β-blockers). The aim was to validate heart rate as a pharmacodynamic endpoint under continuous isoprenaline-induced tachycardia by means of PK-PD modelling of S(−)-atenolol.

Experimental approach:

Groups of WKY rats received a 15 min iv infusion of 5 mg kg−1 S(−)-atenolol, with or without iv infusion of 5 μg kg−1 h−1 isoprenaline. Heart rate was continuously monitored and blood samples were taken.

Key results:

A three-compartment model best described the pharmacokinetics of S(−)-atenolol. The PK–PD relationship was described by a sigmoid Emax model and an effect compartment was used to resolve the observed hysteresis. In the group without isoprenaline, the variability in heart rate (30 b.p.m.) approximated the maximal effect (E max=43±18 b.p.m.), leaving the parameter estimate of potency (EC 50=28±27 ng ml−1) unreliable. Both precise and reliable parameter estimates were obtained during isoprenaline-induced tachycardia: 517±13 b.p.m. (E 0), 168±15 b.p.m. (E max), 49±14 ng ml−1 (EC 50), 0.042±0.012 min−1 (k eo) and 0.95±0.34 (n).

Conclusions and implications:

Reduction of heart rate during isoprenaline-induced tachycardia is a reliable pharmacodynamic endpoint for β-blockers in vivo in rats. Consequently this experimental approach will be used to investigate the relationship between drug characteristics and in vivo effects of different β-blockers.

Keywords: S(−)-atenolol, isoprenaline, PK–PD modelling, rats, heart rate, tachycardia, β-blockers, NONMEM

Introduction

Mechanism-based pharmacodynamic (PD) modelling represents a specific area of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD)2 modelling in which specific drug related properties are linked to the in vivo concentration–effect relationship characterize and predict the time course of drug effects in vivo (Black and Leff, 1983; Breimer and Danhof, 1997; Van Der Graaf and Danhof, 1997). It has been successfully applied to synthetic opiates, adenosine A1 agonists and 5HT1A agonists (Van Der Graaf et al., 1997; Cox et al., 1998; Van Der Graaf et al., 1999; Zuideveld et al., 2004). The possibility of a mechanism-based analysis is dependent on the pharmacological response measured. Although full concentration–time profiles are not always needed (Gabrielsson and Weiner, 1997; Gabrielsson et al., 2000), the pharmacological response should preferably be continuous, reproducible, objective, selective and sensitive for the system under investigation (Dingemanse et al., 1988). Moreover, for extrapolation of of preclinical data to drug response in humans and/or patients, the use of a common pharmacological response endpoint is preferable. Such endpoints include changes in the electroencephalogram, heart rate and body temperature.

Antagonists at β-adrenoceptors (β-blockers) are suitable model drugs for the investigation of the relation between specific drug characteristics on drug action in vivo. As a class, the β-blockers are quite diverse, because they display a high range of values in plasma protein binding and also differ substantially in their potency for binding to β-adrenoceptors (Johnsson and Regardh, 1976; Riddell et al., 1987; Mehvar and Brocks, 2001; Singh, 2005).

The chronotropic effect of the β-blockers is mediated primarily by competition with endogenous agonists (noradrenaline) at the β1-adrenoceptors and is readily available as PD endpoint both in humans and in laboratory animals (Wellstein et al., 1987; Piercy, 1988; Kendall, 1997). However, the reduction in heart rate after β-blocker administration is small and difficult to distinguish from normal variations in heart rate. In clinical investigations, the pharmacological response of β-blockers is, for this reason, evaluated using isoprenaline-induced or exercise-induced tachycardia (Lipworth et al., 1991; Van Bortel et al., 1997; Schafers et al., 1999). Isoprenaline-induced tachycardia is obtained by short infusions of isoprenaline and the effect of isoprenaline on heart rate is evaluated with and without a β-blocker being present. A comparable methodology is used for exercise-induced tachycardia, in which the responsiveness of heart rate to exercise is evaluated with and without β-blockers. In clinical studies, exercise-induced tachycardia is often preferred over isoprenaline-induced tachycardia because of safety issues and practical considerations.

The aim of this study is the validation of heart rate under continuous isoprenaline-induced tachycardia as a PD end point for β-blockers to be used in preclinical PK–PD studies for the development of mechanism-based PK–PD models. A secondary objective is establishment of a concentration–effect relationship for isoprenaline in Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. In the present investigation, a PK–PD modelling approach was used for the validation, which is not mechanism-based.

The use of isoprenaline-induced tachycardia was evaluated since this is most easy to accomplish in the rat, where the increase in heart rate is controllable and can be attained continuously. Tachycardia was induced by a constant intravenous infusion of isoprenaline throughout the experiment. The β-blocker S(−)atenolol was used as a model compound, since it is a β1-selective hydrophilic β-blocker without intrinsic sympathomimetic activity and is eliminated predominantly via the kidneys (Kirch and Gorg, 1982; Reiter, 2004). Furthermore, the active enantiomer of this drug, S(−)-atenolol is not metabolized into (inter)-active metabolites in vivo and has negligible protein binding (Reeves et al., 1978a, 1978b).

Methods

Animals

Animal procedures were performed in accordance with Dutch laws on animal experimentation. The study protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Leiden University (UDEC no. 02112). Male WKY rats (294 g±49, n=39) obtained from Janvier (Le Genest Saint Isle, France) were housed individually at a constant temperature of 21°C and a 12-h light/dark cycle. Before the surgery the rats were acclimatized for at least 5 days. The rats had access to acidified water and food (laboratory chow, Hope Farms, Woerden, The Netherlands) ad libitum, except during the experimental procedures.

Surgery

The rats were anaesthetized with a subcutaneous injection of 0.1 ml per 100 g Ketanest-S and an intramuscular injection of 0.01 ml per 100 g Domitor. During surgery the rats were placed on a heating pad to maintain body temperature at 37°C. Seven days before the experiment, the rats were instrumented with four indwelling blood cannulas (Portex Limited, Hythe, Kent, UK); two cannulas in the right jugular vein (polythene 14 cm, ID 0.58 mm, OD 0.96 mm) for drug administration and one in the left and the right femoral artery (polythene, 4 cm ID 0.28 mm, OD 0.61 mm+20 cm ID 0.58 mm, OD 0.96 mm) for blood sampling and heart-rate measurements, respectively. The blood cannulas were subcutaneously tunnelled and externalized at the dorsal base of the neck. To prevent blood clotting, the arterial cannulas were filled with a 25% (w v−1) polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) solution in a 0.9% saline solution containing 20 IU ml−1 heparin. The venous cannula was filled with a saline solution containing 20 IU ml−1 heparin.

Experimental design

The PK and PD experiments were performed in conscious WKY rats

S(−)-Atenolol: The PK and PD of S(−)-atenolol (5 mg kg−1) were determined in two groups. One group (isoprenaline; n=9) received an intravenous infusion of S(−)-atenolol (5 mg kg−1; 15 min) with isoprenaline-induced tachycardia, the other group (non-isoprenaline; n=8) received an intravenous infusion of S(−)-atenolol without isoprenaline-induced tachycardia. Tachycardia was induced by means of a continuous intravenous infusion of 5 μg kg−1 h−1 of isoprenaline, as this dose provided an adequate effect-time profile with S(−)-atenolol. In the non-isoprenaline group, the continuous infusion consisted of vehicle solution only (0.1% (w w−1) sodium metabisulphite (SMBS)-saline). The continuous infusion of isoprenaline or vehicle started at least 30 min before the start of the S(−)-atenolol infusion. S(−)-atenolol was dissolved in saline and was administered intravenously during 15 min.

Serial arterial blood samples were collected in heparin tubes at predefined time intervals (0, 5, 10, 15, 17.5, 20, 22.5, 27.5, 32.5, 40, 55, 70, 90, 120, 180, 240, 360 and 480 min post-atenolol infusion) for determination of S(−)-atenolol concentrations. Plasma samples were obtained by centrifugation (5 min; 1700 g) and stored at −20°C until analysis. Heart rate was recorded continuously throughout the experiment.

Isoprenaline

Isoprenaline is an extremely potent β-adrenoceptor agonist and a maximal increase in heart rate in rats is obtained with plasma concentrations below the limit of quantification (LOQ). Therefore, the PK and PD of isoprenaline were determined in separate experiments and the concentrations in the PD experiments were predicted using the PK model. For the PK, rats were randomly assigned to two treatment groups of seven animals, which received either a intravenous infusion of 25 or 50 μg kg−1 isoprenaline during 10 min. The doses used provide plasma concentrations, which are sufficiently above the LOQ. As in the S(−)-atenolol experiments, isoprenaline was dissolved in a 0.1% (w w−1) SMBS-saline solution for administration. Serial arterial blood samples were drawn for determination of isoprenaline concentrations. Because of the rapid elimination of isoprenaline, the sampling schemes were slightly different in the two dose groups to ensure adequate estimation of the maximal concentration. For 25 μg kg−1, blood samples were taken at 0, 2, 5, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17.5, 20, 25 and 30 min. For 50 μg kg−1, blood samples were taken at at 0, 1, 3, 5, 9, 10.5, 11, 12, 13, 17.5, 20, 25 and 30 min. In total 14 serial blood samples were collected in heparin tubes containing 0.1% SMBS. Plasma (50–150 μl) was obtained immediately by centrifugation (5 min; 1700 g) and samples were analysed on the same day as the experiment.

For the characterization of the PD, six rats received various continuous intravenous infusions of isoprenaline, to be precise 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2.5 μg kg−1 h−1. Additional data from other experiments in which rats were given a steady state infusion of 5 (n=17) and 10 μg kg−1 h−1 (n=8) were also used in the analysis. Throughout the experiment heart rate was recorded continuously and was used as a PD endpoint.

PD measurements

All experiments started between 0800 and 0900 h to avoid influences of circadian rhythms. Arterial blood pressure and heart rate were measured from the cannulas in the femoral artery using a P10EZ-1 pressure transducer (Viggo-Spectramed BV, Bilthoven, The Netherlands), equipped with a plastic diaphragm dome (TA1017, Disposable Critiflo Dome, BD, Alphen a/d Rijn, The Netherlands). During the experiment the diaphragm dome was flushed with saline at a rate of 500 μl h−1 (Harvard 22-syringe pump, Harvard Apparatus Inc., South Natick, MA, USA). The pressure transducer was placed at the level of the heart of the rats, when in normal position, and connected to a blood pressure amplifier (AP-641G, Nihon Kodhen Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Heart rate was captured from the pressure signal. The signals were passed through a CED 1401plus interface (Cambridge, Electronic Design LTD, Cambridge, England) into a Pentium 4 computer using the data acquisition program Spike 2 (Spike 2 Software, version 3.11, Cambridge, England) and stored on a hard disk for off-line analysis.

Drug analysis

S(−)-atenolol and isoprenaline were quantified using reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) following liquid–liquid extraction as briefly described below.

S(−)-atenolol: The HPLC-system consisted of a LC-10AD HPLC pump (Shimadzu, Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands), a Waters 717 plus autosampler (Waters, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands), and a FP 920 fluorescence detector (Jasco Co; Tokyo, Japan) with an excitation wavelength of 235 nm and an emission wavelength of 300 nm. Chromatography was performed on Spherisorb ODS-2 3 μm column (4.6 mm ID × 100 mm) (Waters, Millford, MA, USA) equipped with a refill guard column (2 mm ID × 20 mm) (Upchurch Scientific, Oak Harbor, WA, USA) packed with pellicular C18 (particle size 20–40 μm) (Alltech, Breda, The Netherlands). The mobile phase consisted of 77.5% (v v−1) 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.4) containing 5 mM octane-sulphonic acid and 22.5% (v v−1) acetonitrile. Sample (50 μl plasma), internal standard (50 μl sotalol 5 μg ml−1 in water), sodium hydroxide solution (3 M, 100 μl), water (200 μl) and ethyl acetate (5 ml) were mixed, shaken (5 min) and centrifuged (10 min, 3400 g). The organic layer was taken and evaporated to dryness. Subsequently the residue was reconstituted in 100 μl mobile phase and 50 μl was injected into the HPLC-system. Linear calibration curves were obtained in the range 40–20 000 ng ml−1 (r>0.995, n=10) and the LOQ for S(−)-atenolol was 40 ng ml−1. The intra- and interassay variabilities were 4 and 11% respectively.

Isoprenaline

The HPLC-system consisted of a LC-10AD HPLC pump (Shimadzu, Hertogenbosch, The Netherlands), a Waters 717 plus autosampler (Waters, Etten-Leur, The Netherlands), a pulse damper (Antec Leyden, Zoeterwoude, The Netherlands) and a digital electrochemical amperometric detector (DECADE, software version 3.02, Antec Leyden, The Netherlands). The optimal working potential for (−)-isoproterenol was +0.65 V. Chromatography was performed on Ultraphere C18 5 μm column (4.6 mm ID × 150 mm; Alltech, Breda, The Netherlands) equipped with a refill guard column (2 mm ID × 20 mm; Upchurch Scientific, Oak Harbor, WA, USA) packed with pellicular C18 (particle size 20–40 μm) (Alltech, Breda, The Netherlands) at a constant temperature of 30°C.

The analysis was preceded by an ion-paired liquid–liquid extraction procedure, in which diphenylboric acid 2-amino-ethanol ester (DPBEA) and tetraoctyl ammoniumbromide (ToABr) were used as complexing agents (Smedes et al., 1982). In short, the sample (50 μl plasma), internal standard (50 μl 3,4-dihydroxy benzylamine hydrobromide (DHBA) 1 μg ml−1 in 0.05 M citric acid solution), DPBEA buffer (250 μl pH 8.8), water (500 μl) and heptane mixture (1.5 ml) were mixed, shaken (3 min) and centrifuged (4000 r.p.m., 8 min). The organic layer was transferred to clean tubes and 2 ml n-octanol was added. Subsequently the organic mixture was back-extracted with 100 μl phosphoric acid solution (87 mM). Finally 30 μl of the aqueous phase was injected into the HPLC system. Linear calibration curves were obtained in the range 1–1000 ng ml−1 (r>0.995, n=7, 50 μl plasma) and the LOQ for Isoprenaline was 0.3 ng ml−1 based on a sample of 150 μl plasma. The intra- and inter-assay variabilities were 5 and 12% respectively.

Data analysis

The PK and PD of S(−)-atenolol and isoprenaline were quantified using nonlinear mixed-effects modelling as implemented in NONMEM software version V, level 1.1 (Beal and Sheiner, 1999). This approach takes into account structural effects and both intra- and inter-individual variability (IIV). Parameters were estimated using the first-order conditional estimation method with η–ɛ interaction (FOCE interaction). Modelling was performed on an IBM-compatible computer (Pentium IV, 1500 MHz) running under Windows XP with the Fortran compiler Compaq Visual Fortran version 6.1. An in-house available S-PLUS 6.0 (Insightful Corp., Seattle, WA, USA) interface to NONMEM version V was used for data processing and management and graphical data display. Goodness-of-fit was determined using the objective function and by visual inspection of the plots of individual predictions and the diagnostic plots of (weighted) residuals. For nested models, a decrease of 10.8 points in the objective function, corresponding to P<0.001 in a χ2-distibution, by adding an additional parameter was considered statistically significant. To compare models which are structurally different, the Akaike Information Criterion (Akaike, 1974) was used.

Pharmacokinetics

PK analysis for S(−)-atenolol was performed by fitting a standard three compartment model to the concentration–time profiles. PK compartmental analysis for isoprenaline was performed by fitting a standard two compartment model to the concentration–time profiles. IIV of the PK parameters was described according to an exponential distribution model:

in which Pi is the individual value of model parameter P, θ is the typical value (population value) of parameter P and ηi is the random deviation of Pi from P. The values of ηi are assumed to be independently normally distributed with mean zero and variance ω2. Selection of an appropriate residual error model was based on inspection of goodness-of-fit plots. On this basis, a proportional error model was selected to describe residual error in the plasma drug concentration:

in which Cobs,ij is the jth observed concentration in the ith individual, Cpred,ij is the predicted concentration, and ɛij accounts for the residual deviation of the model predicted value from the observed value. The values for ɛij are assumed to be independently normally distributed with mean zero and variance σ2. For both S(−)-atenolol and isoprenaline, the PK served as an input for the pharmacological model.

Pharmacodynamics

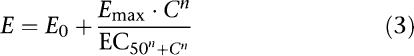

The concentration–effect relationships of S(−)-atenolol and isoprenaline were described using a sigmoidal maximal effect (Emax) model according to:

|

where E is the effect of the drug at concentration C, E0 is the no-drug response (baseline effect), Emax is the maximal drug effect, EC50 is the drug concentration to achieve half-maximal effect and n is the slope factor, which determines the steepness of the curve (i.e., the Hill factor).

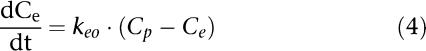

An effect compartment was used to resolve the observed hysteresis between the plasma concentration and the effect of S(−)-atenolol. The following differential equation can be used under the assumption that the effect site concentration equals the plasma concentration in equilibrium.

|

where Cp represents the plasma concentration, Ce represents the effect-site concentration and keo is the first-order rate constant describing drug transport.

For this drug, the PD parameters (P) were modelled as follows:

in which Pi is the individual value of model parameter P, θ is the typical value (population value) of parameter P and ηi is the random deviation of Pi from P. The values of ηi are assumed to be independently normally distributed with mean zero and variance ω2. On this basis of visual inspection, a proportional error model was proposed to describe residual error in the drug effect:

in which Cobs,ij is the jth observed concentration in the ith individual, Cpred,ij is the predicted concentration, and ɛij accounts for the residual deviation of the model predicted value from the observed value. The values for ɛij are assumed to be independently normally distributed with mean zero and variance σ2.

Drugs and chemicals

S(−)-Atenolol, sotalol, (-)-isoprenaline hydrochoride (isoprenaline), DHBA, SMBS, DPBEA and ToABr were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich BV (Zwijndrecht, the Netherlands). Ketanest-S ((S)-ketamine base) was purchased from Parke-Davis (Hoofddorp, The Netherlands). Domitor (medetomidine hydrochloride) was obtained from Pfizer (Capelle a/d IJssel, The Netherlands). PVP was obtained from Brocacef (Maarsen, The Netherlands). Heparin (20 IU ml−1) was obtained from the LUMC (Leiden University Medical Center) Pharmacy (Leiden, The Netherlands) and saline (0.9% NaCl, g v−1) from B Braun Melsungen AG (Melsungen, Germany). The DPBEA buffer consisted of NH4OH–NH4CL buffer (2 M, pH 8.8) with 0.2% (w v−1) DPBEA and 0.5% (w v−1) ethylenediaminetetra acetic acid. The heptane mixture consisted of n-heptane with 1% n-octanol and 0.25% (w v−1) ToABr.

Results

Isoprenaline

Pharmacokinetics

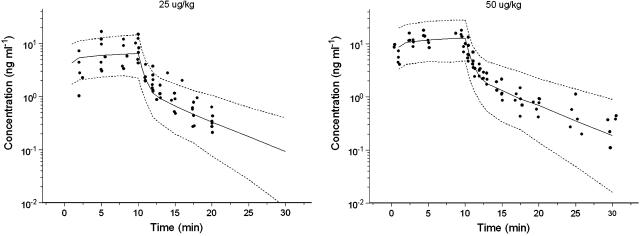

Based on visual inspection of the model fit and the objective function, a two compartment model was selected for isoprenaline. This model adequately described the PK of isoprenaline with estimation of the rate constant of elimination (k10), the rate constant from central to peripheral compartment (k12), the rate constant from peripheral to central compartment (k21) and the central volume of distribution (V1). All PK parameters were estimated precisely with acceptable coefficients of variance (Table 1). The coefficient of variation of the parameter estimates varied between 17 and 47%. Estimation of inter-individual variability was possible for k12, k21 and V1. To validate the PK model for isoprenaline, a bootstrap validation and a predictive check were performed. The population PK estimates were in good agreement with the estimates obtained by fitting 1000 data sets to the final population PK model (Table 1). The bootstrap revealed an uncertainty in estimation of the inter-animal variability on k21 (CV=103%), although the estimate from the bootstrap replicates was nearly identical to the final population estimate. The predictive check showed that the PK model could predict very adequately the time course of isoprenaline after intravenous infusion (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Population estimates of PK parameters (micro constants) for isoprenaline in the rat and estimates of the BS replicates

| Parameter | Value (CV) | Value (CV) BS |

|---|---|---|

| Structural parameters | ||

| K10 (min−1) | 1.32 (20.5%) | 1.33 (21.5%) |

| K12 (min−1) | 0.391 (36.1%) | 0.412 (39.8%) |

| K21 (min−1) | 0.177 (17.6%) | 0.177 (20.2%) |

| V1 (ml) | 79.6 (24.4%) | 83.3 (26.1%) |

| Interindividual variability (IIV) | ||

| ωK122 | 0.213 (46.8%) | 0.215 (54.1%) |

| ωK212 | 0.114 (43.8%) | 0.121 (103.0%) |

| ωV12 | 0.0982 (47.1%) | 0.0900 (49.5%) |

| Residual error | ||

| σPD2 | 0.0796 (22.4%) | 0.0760 (22.7%) |

Abbreviations: BS, bootstrap; CV, coefficient of variation; k10 represents the elimination rate constant, k12 and k21 represent the rate constants describing the transport from and to the second compartment; V1, central volume of distribution (first compartment); ω2, variance of ɛ; σ2, variance of η.

Figure 1.

Visual predictive check of the population PK model for isoprenaline. The range between the dashed lines depicts the 90% interquantile range. The solid line presents the population prediction. The solid dots are the observed concentrations.

Pharmacodynamics

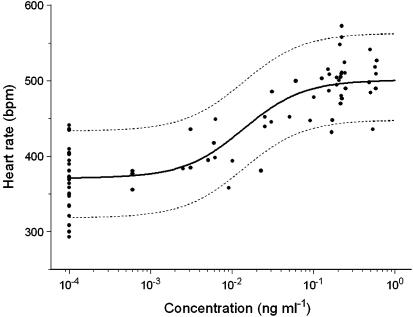

Isoprenaline is an extremely potent β-adrenoceptor agonist and a maximal increase in heart rate is obtained at plasma concentrations below the detection limit in rats. As a result it is not possible to obtain a concentration–effect relationship in a single experiment. Plasma concentrations in the PD experiment were therefore extrapolated using the two-compartment population PK model. Subsequently the concentration–effect relationship of isoprenaline was fitted to a sigmoidal Emax model. The following parameter estimates were obtained: 374.0±7.0 beats min−1 (b.p.m.) for E0, 130±7.7 b.p.m. for Emax, 0.014±0.0044 ng ml−1 for the EC50 and 1.18±0.23 for the Hill coefficient (n). All PD parameters were estimated precisely with acceptable coefficients of variance and inter-animal variability was observed for the baseline only (Table 2). The observed and population-predicted concentration–effect relationship of isoprenaline is shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Population estimates of PD parameters and variabilities for isoprenaline in the rat

| Parameter | Value (CV) |

|---|---|

| Structural parameters | |

| E0 (b.p.m.) | 374 (1.9%) |

| Emax (b.p.m.) | 130 (5.9%) |

| EC50 (ng ml−1) | 0.0138 (31.9%) |

| n | 1.18 (19.3%) |

| Inter-individual variability (IIV) | |

| ωE02 | 860 (29.8%) |

| Residual error | |

| σPD2 | 409 (18.3%) |

Abbreviations: b.p.m., beats per min; CV, coefficient of variation; E0, baseline heart rate, EC50, potency of the drug; Emax, maximal effect of isoprenaline, n, Hill coefficient; PD, pharmacodynamics; ω2, variance of ɛ; σ2, variance of η.

Figure 2.

Population prediction (solid line) and observations (symbols) for the concentration–effect relationship for isoprenaline. The range between the dashed lines depicts the 90% interquantile range.

S(−)-atenolol

Pharmacokinetics

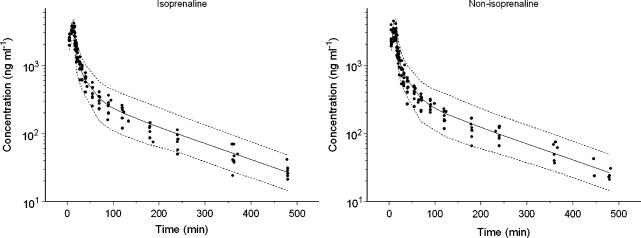

No distinct difference was observed between the isoprenaline and the non-isoprenaline group. On this basis visual inspection of the plots and the objective function a three-compartment PK model was selected as PK model for both groups. All PK parameters were estimated precisely with coefficients of variation ranging between 3 and 36% (Table 3). Interindividual variability was identified for clearance (CL), the volume of the second compartment (V2) and the volume of the third compartment (V3) and correlations between the values of IIV were evaluated by using a full omega matrix. A significant correlation was obtained for CL and V3 and this correlation was estimated in the final model. Validation of the PK model for S(−)-atenolol was performed by a posterior predictive check and a bootstrap analysis. The population estimates were nearly identical to the estimates obtained from the bootstrap replicates (Table 3). In addition the visual predictive check showed that the population PK model could predict closely the time course of S(−)-atenolol in rats (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Population parameter estimates including variabilities and BS replicates for CL, V1, V2, V3 and Q2, Q3

| Parameter | Value (CV) | Value (CV) BS |

|---|---|---|

| Structural parameters | ||

| CL (ml min−1) | 11.7 (3.4%) | 11.7 (3.5%) |

| V1 (ml) | 115 (7.4%) | 114 (8.6%) |

| Q2 (ml min−1) | 15.0 (7.2%) | 15.2 (10.8%) |

| V2 (ml) | 173 (7.7%) | 172 (8.1%) |

| Q3 (ml min−1) | 8.50 (5.3%) | 8.50 (5.6%) |

| V3 (ml) | 849 (4.2%) | 848 (4.2%) |

| Inter-individual variability (IIV) | ||

| ωCL2 | 0.033 (9.8%) | 0.032 (19.9%) |

| ωV22 | 0.170 (28.2%) | 0.169 (29.6%) |

| ωV32 | 0.023 (36.7%) | 0.022 37.5%) |

| ωCL,V32 (covariance) | 0.026 (31.9%) | 0.024 (30.8%) |

| Residual error | ||

| σPD2 | 0.027 (9.5%) | 0.027 (9.6%) |

Abbreviations: BS, bootscrap; CL, clearance; CV, coefficient of variation; Q2, inter-compartmental clearance between first and second compartment; Q3, inter-compartmental clearance between first and third compartment; V1, central volume of distribution first compartment; V2, volume of distribution of second compartment; V3, volume of distribution of third compartment.

Figure 3.

Visual predictive check of the population PK model for S(−)-atenolol. The range between the dashed lines depicts the 90% interquantile range. The solid line presents the population prediction. The solid dots are the observed concentrations.

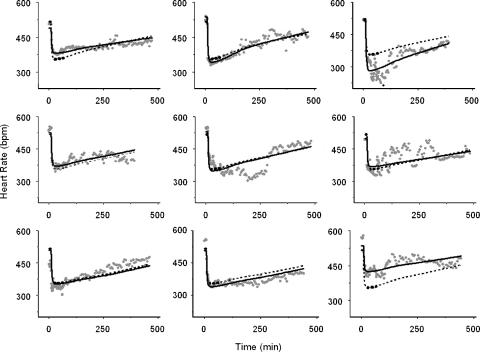

Pharmacodynamics

The PD data were evaluated by means of population PK–PD modelling. A sigmoidal Emax model was used to describe the concentration–effect relationship in both groups and an effect compartment was used to resolve the observed hysteresis in the effects of S(−)-atenolol on the heart rate. In contrast to the PK data, the PD data were analysed separately, since the baseline heart rate differed between the isoprenaline and the non-isoprenaline group.

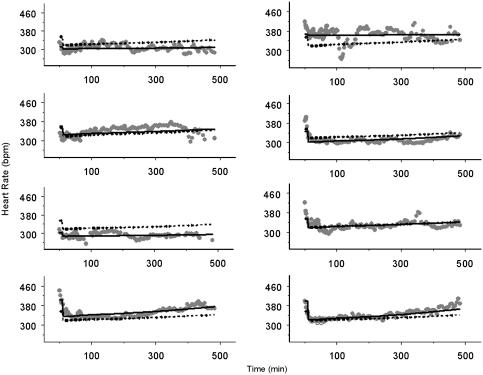

As expected the precise estimation of the population PD parameters in the non-isoprenaline group was more difficult than in the isoprenaline group (Table 4). Although it was possible to obtain estimates of E0 (362±20 b.p.m.), Emax (43±17.7 b.p.m.) and EC50 (28±27 ng ml−1), the coefficient of variation for the EC50 was 97%. Additionally, it was not possible to estimate a Hill coefficient (n) and keo in the non-isoprenaline group, as incorporation of these parameters in the PD model resulted in increased imprecision in the EC50. Inter individual variability was identified for E0 and Emax for this group. The individual plots for the non-isoprenaline group are depicted in Figure 4. Upon administration of S(−)-atenolol some individual rats show a clear decrease in heart rate (i.e. ID 8), while in others the drug effect was difficult to distinguish from normal variations in heart rate (i.e., ID 3).

Table 4.

Population estimates of PD parameters and variabilities for S(−)-atenolol with (ISO) and without (non-ISO) isoprenaline-induced tachycardia

| Parameter | Value (CV) ISO | Value (CV) non-ISO |

|---|---|---|

| Structural parameters | ||

| E0 (b.p.m.) | 517 (2.6%) | 362 (5.5%) |

| Emax (b.p.m.) | −168 (8.8%) | −43.0 (41.2%) |

| EC50 (ng ml−1) | 49.0 (28.8%) | 27.9 (97.1%) |

| Ke0 (min−1) | 0.042 (28.1%) | NE |

| n | 0.950 (36.3%) | NE (fixed at n=1) |

| Interindividual variability (IIV) | ||

| ωE02 | 297 (50.1%) | 1380 (55.4%) |

| omega2Emax | 1860 (49.5%) | 913 (55.9%) |

| Residual error | ||

| σPD2 | 747 (21.6%) | 250 (23.2%) |

Abbreviations: CV, coefficient of variation; E0, baseline heart rate, EC50, potency of the drug, Emax, maximal effect of isoprenaline, keo, equilibrium rate constant for the effect compartment; PD, pharmacodynamics; n, Hill coefficient; NE, not estimated.

Figure 4.

Individual plots of the PD of S(−)-atenolol in the rat, without isoprenaline-induced tachycardia. The solid line, the dashed line and the symbols represent the individual prediction, the population prediction and the heart rate observations respectively.

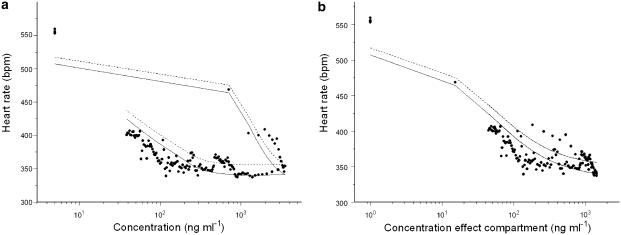

PK–PD analysis of the isoprenaline group resulted in precise estimates for E0 (517±13 b.p.m.), Emax (168±15 b.p.m.), EC50 (49±14 ng ml−1), n (0.95±0.34) and keo (0.042±0.012 min−1) with acceptable coefficients of variation ranging from 4 to 50.1% (Table 4). As already seen in the non-isoprenaline group, inter individual variability was observed for E0 and Emax. With the use of an effect compartment model, the counter clockwise hysteresis loop collapsed and the equilibration half-time between the central and the effect compartment (t1/2=ln 2/keo) was 16.5 min (Figure 5). The individual fits of the model for the isoprenaline group are depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Concentration–effect relationship for S(−)-atenolol for a typical individual rat with isoprenaline-induced tachycardia. (a) Hysteresis loop – observed heart rate plotted against the Cp (b) Collapsed hysteresis loop – observed heart rate plotted against the concentration in the effect compartment (Ce). The solid line, the dashed line and the symbols represent the individual prediction, the population prediction and the heart rate observations respectively.

Figure 6.

Individual plots of the PDs of S(−)-atenolol during isoprenaline-induced tachycardia. The solid line, the dashed line and the symbols represent the individual prediction, the population prediction and the heart rate observations respectively.

Discussion

The overall aim of our research is to develop a mechanism-based PK–PD model for β-blockers, with special reference to in vitro-in vivo correlations and the role of plasma protein binding. To this end the exact quantification of the PD effects of β-blockers is important, and should be evaluated and validated carefully prior to the actual PK–PD studies. In the present study, the heart-rate during continuous isoprenaline-induced tachycardia as a PD endpoint for β-blockers was validated. The results confirmed that reduction of heart rate during isoprenaline-induced tachycardia provided a reliable and reproducible PD measurement for S(−)-atenolol in preclinical PK–PD studies with a small number of individual rats. In addition it is shown that the measurement of the heart-rate effects of S(−)-atenolol without isoprenaline-induced tachycardia resulted in imprecise estimation of the potency of the drug (EC50).

The β-blockers are suitable compounds for investigation of the influence of drug specific properties on in vivo drug action. Much is known about the β-blockers, including the interaction with the β-adrenoceptor and subsequent effects on heart rate (Reiter, 2004). In addition, a wide array of β-blockers is available which differ widely in physicochemical properties and receptor affinity. Moreover, a continuous PD endpoint (heart rate) is readily available in both humans and laboratory animals. The effect on heart rate however is small and therefore difficult to describe accurately (Hoffman and Lefkowitz, 1996). Therefore optimization and validation of the PD measurement for β-blockers is needed.

Isoprenaline- and exercise-induced tachycardia can both be used to improve the PD measurement for the β-blockers. Compared to exercise, induction of tachycardia with isoprenaline is easily achievable in experimental animals and the heart rate response is controllable. Furthermore, the PK of isoprenaline in plasma are known (or can be measured) and this is an advantage for PK–PD modelling.

To our knowledge, the PK and PD of isoprenaline in rats have not been reported earlier. Therefore the establishment of a PK–PD model for this agonist was included in this study. The concentration–time profiles for isoprenaline were described using a two-compartment model and all parameters were estimated with good precision. Isoprenaline-induced tachycardia in the PK–PD studies for S(−)-atenolol was obtained with a 5 μg kg−1 h−1 intravenous infusion. The steady state concentration of isoprenaline for a typical rat of 294 g was 0.43 ng ml−1. The induction of tachycardia at a dose of 5 μg kg−1 h−1 thus approximated the Emax of isoprenaline (Figure 2).

The tachycardia produced by isoprenaline is primarily due to β-adrenoceptor activity in the heart (Chiu et al., 2000). Although β1, β2 and β3 adrenoceptora are present in mammalian heart, the positive chronotropic effect of isoprenaline in vivo are brought about by β1-adrenoceptors (Wellstein et al., 1987; Piercy, 1988; Nandakumar et al., 2005). It is occasionally suggested that β2-adrenoceptors are also involved in the effect on heart rate, however only a small population of functional β2-adrenoceptors is present in the heart of WKY rats (Doggrell and Surman, 1994). Although no in vivo potencies in rat have been reported, isoprenaline is considered an extremely potent β-adrenoceptor agonist and this is confirmed in the present study with an in vivo potency (EC50) of 0.014 ng ml−1 (Waldeck, 2002).

For the development of PK–PD models a continuous measure of drug effect is preferable (i.e., heart-rate, EEG, body temperature). For that reason we investigated the use of a continuous intravenous infusion of isoprenaline in the PD measurement of S(−)-atenolol (Dingemanse et al., 1988). With the use of continuous isoprenaline-induced tachycardia, the effect on heart rate of S(−)-atenolol is clearly distinguishable from normal variations in heart rate and non-stop recording of the pharmacological effect was achievable.

The concentration–time profiles of S(−)-atenolol with and without isoprenaline-induced tachycardia were analysed simultaneously as no differences were found in the PK between both groups (data not shown). The PK parameters obtained from the description of the profiles by a three compartment model are comparable with previous reports (Belpaire et al., 1990, 1993; Mehvar et al., 1990; de Lange et al., 1994). However, the plasma concentrations of atenolol following intravenous administration have been described by a two-compartment model. This difference might be explained by the duration of the experiments, which is usually 2–3 h in the earlier reports, compared with 8 h in our experiment.

In this study, we compared the PD of S(−)-atenolol with and without isoprenaline-induced tachycardia. Some individual profiles in both the isoprenaline and non-isoprenaline group display a large variation in heart rate (i.e., ID: 2; ID:11 and ID:14) which is caused by the measurement. As the heart rate is measured from a cannula in the femoral artery, blood clots in the cannula will sometimes disturb the signal.

The reduction of isoprenaline-induced tachycardia provides a robust PD endpoint for the β-blockers in preclinical investigations. The concentration–effect relationship was described with a sigmoid Emax model and, contrary to the non-isoprenaline group, all PD parameters including inter individual variability on E0 and Emax were estimated precisely.

Baseline heart rate in the non-isoprenaline group was 362±20 b.p.m. and the Emax was a reduction of 43±18 b.p.m.. The variation in heart-rate owing to circadian rhythms, movement and stress is approximately 30 b.p.m. in rats (Oliveira et al., 2004; Lacchini et al, 2001) The Emax of S(−)-atenolol on resting heart rate was thus only slightly larger than the observed variability in heart rate. For that reason, exact quantification of the concentration–effect relationship was complicated in a small number of individuals and thus resulted in uncertainty in the estimation of potency (EC50). Furthermore, the inter animal variability in baseline heart rate approximates the maximal drug effect. In the isoprenaline group, the baseline heart rate was 517±13 b.p.m. and the maximal reduction in heart rate was 168±15 b.p.m.. The Emax with isoprenaline-induced tachycardia is thus clearly distinguishable from the variability in heart rate.

As expected the EC50 of S(−)-atenolol in the isoprenaline group (49±14 ng ml−1) was greater than in the non-isoprenaline group (28±27 ng ml−1) owing to the presence of a higher concentration of the agonist in the system (Rang et al., 1999).

A remarkable finding was the hysteresis observed in the concentration–effect relationship and thus the need for an effect compartment in the PK–PD model (Figure 5). Although the use of an effect compartment for β-blockers is not uncommon in literature for the effect on blood pressure, the effect on heart rate is assumed to be an acute effect, as the β1 receptor is present in the plasma compartment (Ritchie et al., 1998; Brynne et al., 2000; Hocht et al., 2004, 2006). The equilibration half-time between the central compartment and the effect compartment (t1/2) in this study was 16.5 min. Another study of the effect of metoprolol on heart rate in WKY rats reported an equilibration half-time of 36.6 and 20.4 min for 3 and 10 mg kg−1 metoprolol, respectively (Hocht et al., 2006). The delay in effect on heart rate for metoprolol is slightly larger than for S(−)-atenolol, which might be the result of the difference in lipophilicity between both drugs. In theory, hysteresis in the biological effect can be a consequence of biophase equilibration, receptor association and transduction processes. It has been suggested that the myocardial time-concentration profile more closely resembles time-response profile for the acute PD effect of cardioactive drugs (Anderson et al., 1980; Ritchie et al., 1998). Biophase equilibration may therefore be one of the explanations for the observed hysteresis in this study. On the other hand, the observed hysteresis might be the result of the interaction of the β-blocker with the agonist at the receptor. It is known that in order to obtain a maximal increase in heart rate by isoprenaline, a receptor occupancy of only 5% is needed. Thus although atenolol displaces isoprenaline from the receptor, such interaction does not decrease heart rate immediately.

Conclusion

A reproducible and reliable method for the PD measurement of S(−)-atenolol in vivo in rats has been developed. This method allows the continuous measurement of the effect of atenolol and other β-blockers on heart rate during isoprenaline-induced tachycardia and can be used in the development of mechanism-based PK–PD models.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of MCM Blom-Roosemalen, SM Bos-van Maastricht and E Suidgeest and the discussions with Dr F MacIntyre (Pfizer, research and development).

Abbreviations

- b.p.m.

beats min−1

- Ce

concentration in effect compartment

- CL

clearance

- Cp

concentration in plasma

- DHBA

3,4-dihydroxy benzylamine hydrobromide

- DPBEA

diphenylboric acid 2-amino-ethanol ester

- E

effect

- E0

baseline effect

- EC50

concentration to achieve half-maximal effect (potency)

- Emax

maximal effect

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- IIV

inter-individual (interanimal) variability

- k10

elimination rate constant

- k12

rate constant describing transport from central to peripheral compartment

- k21

rate constant describing transport from peripheral to central compartment

- keo

first-order rate constant describing transport to effect compartment

- n

Hill coefficient

- PD

pharmacodynamics

- PK

pharmacokinetics

- PVP

polyvinylpyrrolidone

- Q2

inter-compartmental clearance between first and second compartment

- Q3

inter-compartmental clearance between first and third compartment

- SMBS

sodium metabisulphite

- ToABr

tetraoctyl ammoniumbromide

- V1

central volume of distribution (first compartment)

- V2

volume of distribution of second compartment

- V3

volume of distribution of third compartment

- ɛ

residual variability

- η

inter-individual variability

- θ

value for population parameter P

- σ2

variance of η

- χ2

chi square distribution

- ω2

variance of ɛ

Conflict of interest

These investigations were financially supported by Pfizer Ltd, Sandwich, UK.

References

- Akaike A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automatic Control. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Patterson E, Conlon M, Pasyk S, Pitt B, Lucchesi BR. Kinetics of antifibrillatory effects of bretylium: correlation with myocardial drug concentrations. Am J Cardiol. 1980;46:583–592. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(80)90507-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal SL, Sheiner LB. NONMEM Users Guide. University of California at San Fransisco, San Fransisco, CA; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Belpaire FM, De Smet F, Vynckier LJ, Vermeulen AM, Rosseel MT, Bogaert MG, et al. Effect of aging on the pharmcokinetics of atenolol, metoprolol and propranolol in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;254:116–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belpaire FM, Rosseel MT, Vermeulen AM, De Smet F, Bogaert MG. Stereoselective pharmacokinetics of atenolol in the rat: influence of aging and of renal failure. Mech Ageing Dev. 1993;67:201–210. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(93)90123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JW, Leff P. Operational models of pharmacological agonism. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1983;220:141–162. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1983.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breimer DD, Danhof M. Relevance of the application of pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modelling concepts in drug development–The ‘Wooden Shoe' paradigm. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:259–267. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brynne L, Paalzow LK, Karlsson MO. Consequence of exercise on the cardiovascular effects of l-propranolol in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:1201–1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu CC, Lin YT, Tsai CH, Liang JC, Chiang LC, Wu JR, et al. Pharmacological effects of an aldehyde type alpha/beta-adrenoceptor blocking agent with vasodilating properties. Gen Pharmacol. 2000;34:391–400. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(01)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox EH, Kerbusch T, Van Der Graaf PH, Danhof M. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of the electroencephalogram effect of synthetic opioids in the rat: correlation with the interaction at the mu-opioid receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;284:1095–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange EC, Danhof M, de Boer AG, Breimer DD. Critical factors of intracerebral microdialysis as a technique to determine the pharmacokinetics of drugs in rat brain. Brain Res. 1994;666:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingemanse J, Danhof M, Breimer DD. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of CNS drug effects: an overview. Pharmacol Ther. 1988;38:1–52. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(88)90101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doggrell SA, Surman AJ. Functional beta-adrenoceptors in the left atrium of normotensive and hypertensive rats. J Auton Pharmacol. 1994;14:425–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1994.tb00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsson J, Weiner D. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Data Analysis: Concepts and Applications. Swedish Pharmaceutical Press: Stockholm; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrielsson J, Jusko WJ, Alari L. Modeling of dose-response-time data: four examples of estimating the turnover parameters and generating kinetic functions from response profiles. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2000;21:41–52. doi: 10.1002/1099-081x(200003)21:2<41::aid-bdd217>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocht C, Di Verniero C, Opezzo JA, Bramuglia GF, Taira CA. Pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic (PK–PD) modeling of cardiovascular effects of metoprolol in spontaneously hypertensive rats: a microdialysis study. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;373:310–318. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocht C, Di Verniero C, Opezzo JAW, Taira CA. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic properties of metoprolol in chronic aortic coarctated rats. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Archives of Pharmacology. 2004;370:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0945-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BB, Lefkowitz RJ.Catecholamines, sympathomimetic drugs, and adrenergic receptor antagonists Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 1996McGraw-Hill: New York; 199–248.In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, Ruddon RW, Goodman Gillman G (eds) [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson G, Regardh CG. Clinical pharmacokinetics of beta-adrenoreceptor blocking drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1976;1:233–263. doi: 10.2165/00003088-197601040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall MJ. Clinical relevance of pharmacokinetic differences between beta blockers. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:15J–19J. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00833-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirch W, Gorg KG. Clinical pharmacokinetics of atenolol–a review. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 1982;7:81–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03188723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacchini S, Ferlin EL, Moraes RS, Ribeiro JP, Irigoyen MC. Contribution of nitric oxide to arterial pressure and heart rate variability in rats submitted to high-sodium intake. Hypertension. 2001;38:326–331. doi: 10.1161/hy0901.091179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipworth BJ, Irvine NA, McDevitt DG. A dose-ranging study to evaluate the beta 1-adrenoceptor selectivity of bisoprolol. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;40:135–139. doi: 10.1007/BF00280067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehvar R, Brocks DR. Stereospecific pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of beta-adrenergic blockers in humans. J Pharm Sci. 2001;4:185–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehvar R, Gross ME, Kreamer RN. Pharmacokinetics of atenolol enantiomers in humans and rats. J Pharm Sci. 1990;79:881–885. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600791007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar K, Bansal SK, Singh R, Bodhankar SL, Jindal DP, Coumar MS, et al. Selective beta(1)-adrenoreceptor blocking activity of newly synthesized acyl amino-substituted aryloxypropanolamine derivatives, DPJ 955 and DPJ 890, in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57:515–520. doi: 10.1211/0022357055768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira EL, Cardoso LM, Pedrosa ML, Silva ME, Dun NJ, Colombari E, et al. A low protein diet causes an increase in the basal levels and variability of mean arterial pressure and heart rate in Fisher rats. Nutr Neurosci. 2004;7:201–205. doi: 10.1080/10284150412331279827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piercy V. Method for assessing the activity of drugs at beta 1- and beta 2-adrenoceptors in the same animal. J Pharmacol Methods. 1988;20:125–133. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(88)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang H, Dale M, Ritter J. Pharmacology 1999Philadelphia: Lippincott; 4th edn [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PR, Barnfield DJ, Longshaw S, McIntosh DA, Winrow MJ. Disposition and metabolism of atenolol in animals. Xenobiotica. 1978a;8:305–311. doi: 10.3109/00498257809060955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PR, McAinsh J, McIntosh DA, Winrow MJ. Metabolism of atenolol in man. Xenobiotica. 1978b;8:313–320. doi: 10.3109/00498257809060956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter MJ. Cardiovascular drug class specificity: beta-blockers. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2004;47:11–33. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddell JG, Harron DW, Shanks RG. Clinical pharmacokinetics of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists. An update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1987;12:305–320. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198712050-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie RH, Morgan DJ, Horowitz JD. Myocardial effect compartment modeling of metoprolol and sotalol: importance of myocardial subsite drug concentration. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87:177–182. doi: 10.1021/js9702776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafers RF, Karl I, Mennicke K, Daul AE, Philipp T, Brodde OE. Ketotifen and cardiovascular effects of xamoterol following single and chronic dosing in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47:59–66. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh BN. Beta-Adrenergic blockers as antiarrhythmic and antifibrillatory compounds: an overview. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2005;10 Suppl 1:S3–S14. doi: 10.1177/10742484050100i402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedes F, Kraak JC, Poppe H. Simple and fast solvent extraction system for selective and quantitative isolation of adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine from plasma and urine. J Chromatogr. 1982;231:25–39. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)80506-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bortel LM, de Hoon JN, Kool MJ, Wijnen JA, Vertommen CI, Van Nueten LG. Pharmacological properties of nebivolol in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;51:379–384. doi: 10.1007/s002280050217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Graaf PH, Danhof M. Analysis of drug-receptor interactions in vivo: a new approach in pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modelling. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;35:442–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Graaf PH, Van Schaick EA, Mathôt RA, Ijzerman AP, Danhof M. Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of the effects of N6-cyclopentyladenosine analogs on heart rate in rat: estimation of in vivo operational affinity and efficacy at adenosine A1 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Graaf PH, Van Schaick EA, Visser SA, De Greef HJ, Ijzerman AP, Danhof M. Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of antilipolytic effects of adenosine A(1) receptor agonists in rats: prediction of tissue-dependent efficacy in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:702–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldeck B. Beta-adrenoceptor agonists and asthma – 100 years of development. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;445:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellstein A, Palm D, Belz GG, Butzer R, Polsak R, Pett B. Reduction of exercise tachycardia in man after propranolol, atenolol and bisoprolol in comparison to beta-adrenoceptor occupancy. Eur Heart J. 1987;8 Suppl:M:3–M:8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/8.suppl_m.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuideveld KP, Van Der Graaf PH, Newgreen D, Thurlow R, Petty N, Jordan P, et al. Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of 5-HT1A receptor agonists: estimation of in vivo affinity and intrinsic efficacy on body temperature in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:1012–1020. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]