Abstract

Background and purpose:

Ultralow doses of naltrexone, a non-selective opioid antagonist, have previously been found to augment acute morphine analgesia and block the development of tolerance to this effect. Since morphine tolerance is dependent on the activity of μ and δ receptors, the present study investigated the effects of ultralow doses of antagonists selective for these receptor types on morphine analgesia and tolerance in tests of thermal and mechanical nociception.

Experimental approach:

Effects of intrathecal administration of μ-receptor antagonists, CTOP (0.01 ng) or CTAP (0.001 ng), or a δ-receptor antagonist, naltrindole (0.01 ng), on spinal morphine analgesia and tolerance were evaluated using the tail-flick and paw-pressure tests in rats.

Key results:

Both μ and δ antagonists augmented analgesia produced by a sub-maximal (5 μg) or maximal (15 μg) dose of morphine. Administration of the antagonists with morphine (15 μg) for 5 days inhibited the progressive decline of analgesia and prevented the loss of morphine potency. In animals exhibiting tolerance to morphine, administration of the antagonists with morphine produced a recovery of the analgesic response and restored morphine potency.

Conclusions and implications:

Combining ultralow doses of μ- or δ-receptor antagonists with spinal morphine augmented the acute analgesic effects, inhibited the induction of chronic tolerance and reversed established tolerance. The remarkably similar effects of μ- and δ-opioid receptor antagonists on morphine analgesia and tolerance are interpreted in terms of blockade of the latent excitatory effects of the agonist that limit expression of its full activity.

Keywords: analgesia, antagonist, CTAP, CTOP, morphine, naltrindole, opioid, tolerance, ultralow dose

Introduction

Morphine and related opioid drugs are indispensable for the management of severe pain syndromes. However, their chronic use can induce tolerance, a response that is characterized by a loss of drug potency and that limits their clinical potential. The mechanisms underlying opioid analgesic tolerance are complex and involve adaptations in opioid-receptor activity at the cellular/molecular level (Chakrabarti et al., 2001; He et al., 2002; Bailey et al., 2006), and at the level of spinal or supraspinal neuronal networks signalling nociception (Mao et al., 1995; Gardell et al., 2002; Trang et al., 2005).

In the dorsal horn, opioid-receptor agonists act on presynaptic receptors localized on the terminals of high-threshold primary afferents to decrease the activity of voltage-dependent calcium channels and inhibit the release of nociceptive neurotransmitters (Werz and Macdonald, 1983), an effect that partly contributes to their potent analgesic property. Chronic exposure to opioids, however, induces a paradoxical hyperalgesia that counteracts their analgesic actions and thus produces tolerance (Mao et al., 1994; Ossipov et al., 2003). The basis for this opioid-induced hyperalgesia remains unclear, but experimental evidence suggests that diverse factors – upregulation of sensory neuropeptide transmitters (Menard et al., 1996; Powell et al., 2000; Gardell et al., 2002), increased dynorphin expression (Vanderah et al., 2000), downregulation of excitatory amino-acid transporters (Mao et al., 2002), and glial cell activation (Raghavendra et al., 2002) – play a role in its origin at the spinal level. Indeed, pharmacological interventions that limit the influence of some of these factors have been reported to block and/or reverse the development of opioid analgesic tolerance (Mao et al., 1994, 2002; Dunbar and Yaksh, 1996; Menard et al., 1996; Powell et al., 2000, 2003; Gardell et al., 2002; Raghavendra et al., 2002).

Electrophysiological studies, however, have reported that opioids can exert a stimulatory action on nociceptive sensory neurons, an effect that could contribute to the opioid-induced hyperalgesia implicated in the development of tolerance. Low-dose morphine has been reported to increase the activity of rat dorsal horn neurons driven by noxious input (Dickenson and Sullivan, 1986). Chen and Huang (1991) have shown that μ-opioid-receptor activation augments NMDA-evoked depolarization of rat substantia gelatinosa neurons. Crain and Shen (1990) have demonstrated that very low doses of morphine and related opioid receptor agonists increase the calcium-dependent phase of action potentials in mouse sensory dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, an effect blocked by ultralow doses of competitive opioid receptor antagonists such as naltrexone. They have postulated that the low-dose facilitatory actions of opioid agonists lead to a physiological antagonism of the classical inhibitory effects that occur at higher doses of these agents, and that sensitization to such actions, following a sustained drug exposure, produces tolerance. Consistent with this proposal, very low doses of opioid antagonists have been shown to augment acute morphine analgesia and inhibit the development of morphine tolerance in a mouse model (Crain and Shen, 1995).

Recently, using a rat model of spinal morphine analgesia, we showed that ultralow doses of naltrexone augment the analgesic actions of morphine, block the induction of tolerance to chronic morphine, and reverse established tolerance (Powell et al., 2002). Following studies have confirmed the effects of ultralow doses of systemic naltrexone on morphine analgesia and tolerance, and have additionally described the strain- and age-related dependency of these effects (Hamann et al., 2004; Terner et al., 2006). Considering that naltrexone is nonselective for opioid receptors and that tolerance to morphine involves the activity of μ- as well as δ-opioid receptors (Fundytus et al., 1995; Zhu et al., 1999), the atypical modulatory effects of the antagonist may result from its action on one or more opioid receptor type. Thus, to determine the potential role of μ and δ receptors in the expression of such effects, the present study examined the effects of extremely low doses of antagonists selective for these receptor types on both acute morphine analgesia and chronic morphine tolerance in a spinal analgesia model (Yaksh and Rudy, 1976), using tests of thermal and mechanical nociception.

Methods

The experiments were conducted using adult male Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River, St Constant, QC, Canada) weighing between 200–250 g. Animals were housed individually in standard laboratory cages, maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle, and provided with food and water ad libitum. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Animals for Research Act, the Guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care and the Queen's University Animal Care Committee.

Intrathecal catheterization and drug administration

The surgical placement of chronic indwelling intrathecal catheters (polyethylene PE 10 tubing, 7.5 cm) into the spinal subarachnoid space was made under 4% halothane anaesthesia, using the method of Yaksh and Rudy (1976). Briefly, the anaesthetized animal was placed prone in a stereotaxic frame, a small incision made at the back of the neck, and the atlanto-occipital membrane overlying the cisterna magna was exposed and punctured with a blunt needle. The catheter was inserted through the cisternal opening and slowly advanced caudally to position its tip at the lumbar enlargement. The rostral end of the catheter was exteriorized at the top of the head and the wound closed with sutures. Animals were allowed 3–4 days recovery from surgery, and only those free from neurological deficits, such as hindlimb or forelimb paralysis or gross motor dysfunction, were included in the study. All drugs were injected intrathecally through the exteriorized portion of the catheter at a volume of 10 μl, followed by a 10 μl volume of 0.9% saline to flush the catheter.

Assessment of nociception

The response to brief nociceptive stimuli was tested using two spinal reflex tests: the tail-flick test and the paw-pressure test, as described previously (Powell et al., 1999, 2002). The tail-flick test was used to measure the response to a thermal nociceptive stimulus. Radiant heat was applied to the distal third of the animal's tail, and the response latency for tail withdrawal from the source was recorded using an analgesia meter. The stimulus intensity was adjusted to yield baseline response latencies between 2–3 s. To minimize tail damage, a cutoff of 10 s was used as an indicator of maximum antinociception. The paw-pressure test was used to measure the response to a mechanical nociceptive stimulus. Pressure was applied to the dorsal surface of the hind paw, using an inverted air-filled syringe connected to a gauge, and the value at which the animal withdrew its paw was recorded. A maximum cutoff pressure of 300 mmHg was used to avoid tissue damage. Previous experience has established that there is no significant interaction between the tail-flick and paw-pressure tests.

Induction of chronic tolerance to morphine

Animals were given a single intrathecal injection of saline or morphine (15 μg) once daily between 0900 AM and 1100 AM for 5 days. Nociceptive testing was performed before drug injection to establish the baseline response level, and 30 min post-injection to determine the drug effect. Previous studies in this laboratory have shown that the peak antinociceptive response to morphine occurs 30 min post-injection. On day 6, cumulative morphine dose–response curves were generated to determine acute opioid potency in the control and treatment groups. Each animal was given ascending doses of morphine at 30-min intervals and tested 25 min after each injection. This protocol was continued until a maximal antinociceptive response was obtained in both the tail-flick and paw-pressure test. The morphine dose–response curves were constructed and the agonist ED50 values determined from each dose–response curve. The development of tolerance was revealed by a progressive decline of morphine antinociception over the 5-day treatment period, a rightward shift of the acute morphine dose–response curve, and a significant increase in the morphine ED50 value.

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on acute morphine antinociception

The effects of opioid antagonists on the acute antinociceptive effect of intrathecal morphine were determined by coadministering a fixed low dose of the antagonist under investigation with a submaximal (5 μg) or maximal (15 μg) dose of the agonist. Thus, morphine was delivered in combination with the μ-receptor antagonist, CTOP (D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2) (0.01 ng) or CTAP (D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2) (0.001 ng), or the δ-receptor antagonist, naltrindole (0.01 ng). Nociceptive testing was performed every 10 min post-injection for the first 60 min and every 30 min for the following 120 min.

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on the induction of chronic morphine tolerance

The effects of opioid antagonists on the induction of morphine tolerance were determined by coadministering a fixed dose of CTOP (0.01 ng), CTAP (0.001 ng) or naltrindole (0.01 ng) with intrathecal morphine (15 μg) for 5 days. Nociceptive testing was performed as described above. Control animals received the antagonists in combination with saline. Cumulative dose–response curves to acute intrathecal morphine were generated in all treatment groups on day 6. The effect of antagonists on morphine tolerance was evaluated by observing their action on the sustainability of the response to daily injection of morphine and on morphine ED50 values derived from the cumulative dose–response curves.

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on established morphine tolerance

The effects of opioid antagonists on established morphine tolerance were determined by first exposing the animals to chronic morphine and then delivering an antagonist in combination with chronic morphine. Intrathecal morphine (15 μg) was injected once daily from days 1 to 5, and its action evaluated using both the tail-flick and paw-pressure test. On each of the following 5 days (days 6–10), CTAP (0.001 ng), naltrindole (0.01 ng) or saline were administered alone or in combination with morphine (15 μg) to the animals pre-exposed to the agonist. Control animals received saline for 10 days. On day 11, cumulative morphine dose–response curves were generated as described above. The potential of opioid antagonists to reverse tolerance was evaluated by observing the recovery of morphine-induced antinociception and the reversal of changes in morphine ED50 values derived from the cumulative dose–response curves.

Data analysis

Tail-flick and paw-pressure values were converted to a maximum percentage effect (MPE): MPE=100 × (post-drug response–baseline response)/(maximum response–baseline response). Data represented in the figures are expressed as mean (±s.e.m.). The ED50 values were determined using a nonlinear regression analysis (Prism 2, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance (P<0.05, 0.01, or 0.001) was determined using a one-way analysis of variance followed by a Student's Newman–Keuls post hoc test for multiple comparisons between groups.

Drugs

Morphine sulphate was obtained from BDH Pharmaceuticals (Toronto, Ontario Canada). CTOP was obtained from BACHEM Bioscience Inc. (King of Prussia, PA, USA). CTAP and naltrindole were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co (St Louis, MO, USA). All drugs were dissolved in physiological saline (0.9%).

Results

The baseline latency values in the tail-flick test ranged between 1.8 and 2.8 s, and the threshold values for withdrawal response in the paw-pressure test ranged between 60 and 100 mm Hg. These values are representative of the baseline responses in all the experiments represented in this study. Each drug treatment or drug combination was tested using a separate group of animals.

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on acute morphine antinociception

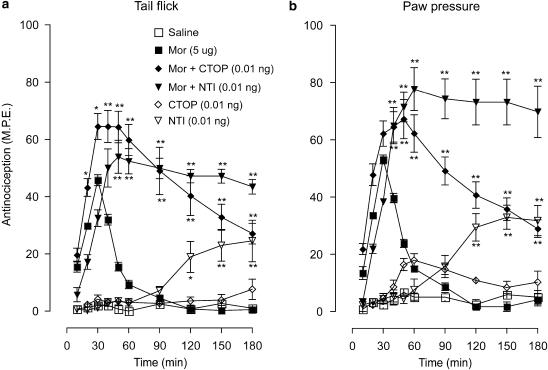

Submaximal morphine dose

The effects of the μ-receptor antagonist, CTOP (0.01 ng) and the δ-receptor antagonist, naltrindole (0.01 ng), on the antinociceptive actions of a submaximal dose of morphine (5 μg) in the tail-flick and paw-pressure test are represented in Figure 1a and b. In both tests, intrathecal morphine produced approximately 50% maximal response that peaked at 30 min and was followed by a rapid recovery to baseline values 60 min post-injection. Coadministration of CTOP or naltrindole increased the peak morphine effect and markedly extended the response. The response to the CTOP–morphine combination showed a slow recovery, but that to the naltrindole–morphine combination remained at the peak level for the duration of the 180 min test period. Injection of CTOP alone did not elicit a significant response; however, naltrindole alone produced a weak effect that had delayed onset and reached 20% and 30% of the maximal value in the tail-flick and paw-pressure test, respectively.

Figure 1.

Time course of the effects of ultralow doses of intrathecal CTOP (0.01 ng) and naltrindole (NTI; 0.01 ng) on the acute antinociceptive action of a submaximal dose of morphine (Mor; 5 μg) in the (a) tail-flick and (b) paw-pressure test. Morphine was administered with CTOP or NTI as a single intrathecal injection. Nociceptive testing was performed every 10 min post-injection for the first hour and every 30 min for the following 2 h. The data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. for five to six animals. Significant differences from the action of morphine alone: *P<0.01, **P<0.001. CTOP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; NTI, naltrindole.

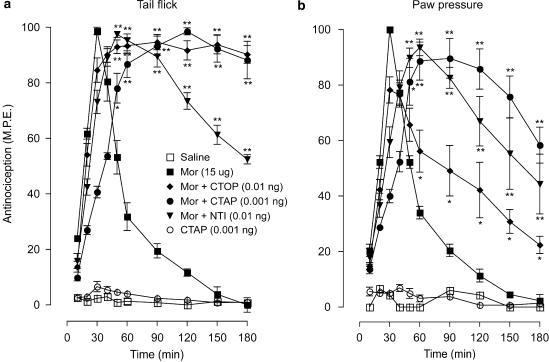

Maximal morphine dose

The effects of CTOP, naltrindole and CTAP (an antagonist with very high selectivity for μ receptors) on the antinociceptive effects of a maximal dose of morphine (15 μg) in the tail-flick and paw-pressure test are represented in Figures 2a and b. Morphine produced a peak effect in both tests at 30 min, followed by a complete recovery 90 min post-injection. In the tail-flick test (Figure 2a), the co-injection of CTOP (0.01 ng), CTAP (0.001 ng) or naltrindole (0.01 ng) with morphine delayed the onset of the peak response to 60 min, but markedly increased the duration of the response. Indeed, both CTOP and CTAP maintained the agonist-induced response at the maximal level for the duration of the 180 min test period. The response to the naltrindole–morphine combination exhibited a slow recovery towards the baseline, but was sustained well above the response produced by morphine alone during the testing period. In the paw-pressure test (Figure 2b), the antagonists similarly delayed the onset of the peak morphine effect, but maintained the antinocieptive response significantly above control values during the test period. As was observed in the preceding tests with CTOP, injection of CTAP alone did not produce a significant effect in either test. None of the animals in these tests showed visible signs of motor dysfunction, and animals in all treatment groups showed full recovery from drug effects (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Time course of the effects of ultralow doses of intrathecal CTOP (0.01 ng), CTAP (0.001 ng) and naltrindole (NTI; 0.01 ng) on the acute antinociceptive action of a maximal dose of morphine (Mor; 15 μg) in the (a) tail-flick and (b) paw-pressure test. Morphine was administered with CTOP, CTAP, or NTI as a single intrathecal injection. Nociceptive testing was performed every 10 min post-injection for the first hour and every 30 min for the following 2 h. The data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. for four to six animals. Significant differences from the action of morphine alone: *P<0.01, **P<0.001. CTAP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; CTOP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; NTI, naltrindole.

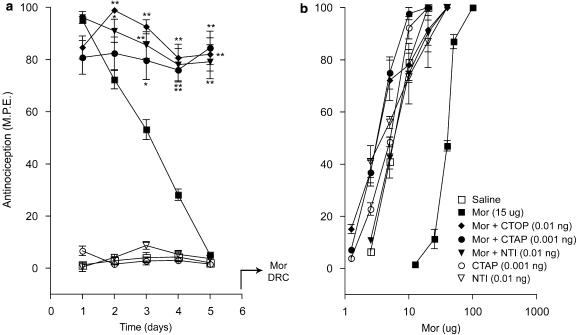

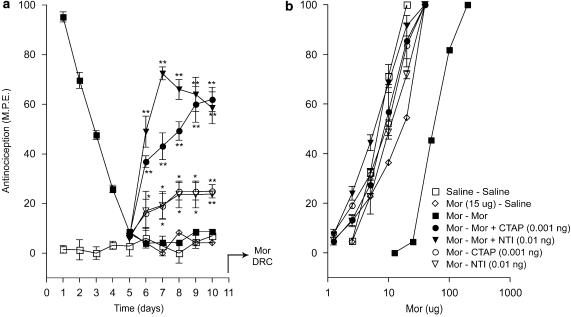

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on the induction of morphine tolerance

Figure 3 shows the effects of CTOP, CTAP and naltrindole on the antinociceptive effects produced by a maximal dose of morphine (15 μg) administered daily for 5 days, in the tail-flick test. Since the preceding acute tests (Figure 2) revealed that the administration of these antagonists with morphine resulted in a delayed onset of the peak antinociceptive effect, the response elicited by each drug combination in the chronic tolerance experiments was measured 60 min post-injection to reflect the peak effect. As expected, injection of morphine alone on day 1 elicited a maximal response (Figure 3a), but injections on successive days resulted in a progressive decline of the response that reached baseline values on day 5. The coadministration of CTOP, CTAP or naltrindole with the agonist arrested this decline, and sustained the antinociceptive response at 80–90% of the maximal value for the duration of the 5-day test period. Chronic administration of the antagonists without morphine did not elicit a significant response. Figure 3b shows the cumulative dose–response curves to acute morphine derived on day 6 in the treatment groups represented in Figure 3a. As illustrated, the dose–response curve obtained in the chronic morphine group showed a marked rightward shift relative to that in the chronic saline group. However, this shift did not occur in groups that had received morphine in combination with CTOP, CTAP or naltrindole. The dose–response curves in groups that had received chronic treatment with antagonists alone overlapped with that obtained in animals that had received chronic saline.

Figure 3.

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on the induction of morphine tolerance in the tail-flick test. (a) Time course of the effects of intrathecal CTOP (0.01 ng), CTAP (0.001 ng), and naltrindole (NTI; 0.01 ng) on the induction of tolerance to chronic morphine (Mor; 15 μg) in the tail-flick test. Morphine and CTOP, CTAP, or NTI were administered as a single intrathecal injection once daily for 5 days. Nociceptive testing was performed 60 min after each injection. The data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. for four to seven animals. (b) Cumulative dose–response curves for the antinociceptive effects of acute morphine in the treatment groups represented in (a). The dose–response curves were obtained 24 h after termination of the chronic drug treatment. Ascending doses of intrathecal morphine were given every 30 min and the antinocieptive response was measured in the tail-flick test 25 min after each injection. Significant differences from the action of morphine alone: *P<0.05, **P<0.01. CTAP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; CTOP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; NTI, naltrindole.

The effects of CTOP, CTAP and naltrindole on the induction of morphine tolerance in the paw-pressure test are shown in Figure 4. While the CTAP–morphine combination showed a similar response pattern as seen in the tail-flick test, the response produced by the CTOP–morphine or naltrindole–morphine combination from day 1 to 3 showed a decline parallel to the response produced by morphine alone (Figure 4a). However, while the morphine-induced response declined to baseline values on day 5, the response to the two combinations levelled off at 40% to 50% of the maximal value on days 4 and 5, respectively. The cumulative dose–response curves to acute morphine in the paw-pressure test (Figure 4b) showed a similar pattern as those observed in the tail-flick test.

Figure 4.

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on the induction of morphine tolerance in the paw-pressure test. (a) Time course of the effects of intrathecal CTOP (0.01 ng), CTAP (0.001 ng) and naltrindole (NTI; 0.01 ng) on the induction of tolerance to chronic morphine (Mor; 15 μg) in the paw-pressure test. Morphine and CTOP, CTAP, or NTI were administered as a single intrathecal injection once daily for 5 days. Nociceptive testing was performed 60 min after each injection. The data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. for four to seven animals. (b) Cumulative dose–response curves for the antinociceptive effects of acute morphine in the treatment groups represented in (a). The dose–response curves were obtained 24 h after termination of the chronic drug treatment. Ascending doses of intrathecal morphine were given every 30 min and the antinocieptive response was measured in the paw-pressure test 25 min after each injection. Significant differences from the action of morphine alone: *P<0.05, **P<0.01. CTAP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; CTOP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; NTI, naltrindole.

The morphine ED50 values derived from the cumulative dose–response curves (Figures 3b and 4b) are shown in Table 1. In both nociception tests, the ED50 values in the chronic morphine treatment group showed a five- to sevenfold increase over values in the chronic saline treatment group, reflecting a significant loss of morphine potency. However, this increase in ED50 value was completely prevented in groups that received morphine in combination with a low dose of CTOP, CTAP or naltrindole. Indeed, the values obtained in these treatment groups were comparable to those obtained in groups that had received the antagonists alone or saline. Thus, all three opioid antagonists prevented the loss of agonist potency associated with development of morphine tolerance.

Table 1.

The effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on the induction of tolerance to intrathecal morphine

| Chronic treatment (5 days) |

ED50 (mean±s.e.m.) (mg) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Tail flick | Paw pressure | |

| Saline | 5.8±0.5 | 5.1±1.4 |

| Morphine (15 μg) | 31.6±1.8a | 39.0±2.0a |

| Morphine/CTOP (0.01 ng) | 3.2±0.3 | 7.7±1.4 |

| Morphine/CTAP (0.001 ng) | 3.1±0.3 | 5.7±0.9 |

| Morphine/Naltrindole (0.01 ng) | 3.5±1.4 | 3.5±1.4 |

| CTAP (0.001 ng) | 4.6±0.5 | 7.7±0.5 |

| Naltrindole (0.01 ng) | 3.6±0.6 | 10.0±0.7 |

Following the end of the 5-day chronic treatment period, cumulative dose–response curves to acute morphine were generated on day 6, and ED50 values for morphine were derived from these curves.

Significant differences from saline group (P<0.001).

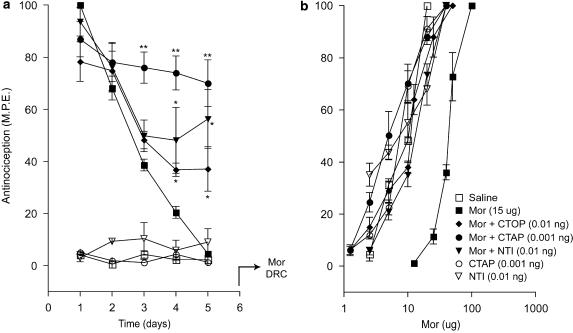

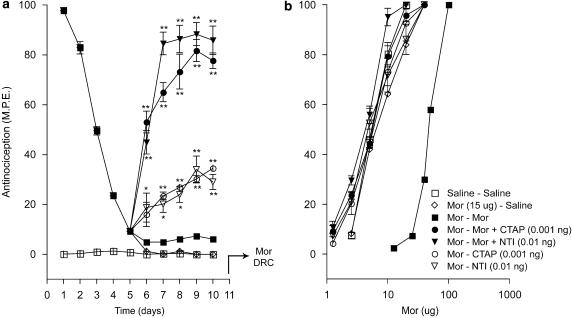

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on established morphine tolerance

The effects of CTAP and naltrindole in animals rendered tolerant to the antinociceptive effect of morphine in the tail-flick test are shown in Figure 5. Chronic morphine exposure resulted in a decline of the antinociceptive response to baseline values on day 5, and it remained at this level upon continuation of treatment with the opioid agonist or its substitution with saline from day 6 to 10 (Figure 5a). However, the addition of CTAP (0.001 ng) or naltrindole (0.01 ng) to morphine from day 6 to 10 in animals pre-exposed to morphine for 5 days (morphine tolerant group) produced a robust recovery of the antinociceptive response, reaching 75% and 80% of the maximal value, respectively. Interestingly, administration of CTAP or naltrindole alone to the morphine-tolerant group elicited a weak antinociceptive response. This response was discernable on day 6, and on following days it reached 25% of the maximal value in the tail-flick test. Figure 5b shows the cumulative dose–response curves to acute morphine derived on day 11 in the treatment groups represented in Figure 5a. A 10-day morphine exposure resulted in a rightward shift of the agonist dose–response curve relative to an equivalent saline exposure. However, this rightward shift did not occur in groups that had received morphine with low doses of CTAP or naltrindole from day 6 to 10. The dose–response curves in groups treated with CTAP or naltrindole alone from day 6 to 10 overlapped with those obtained in animals that had received chronic saline.

Figure 5.

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on established morphine tolerance in the tail-flick test. (a) Time course of the effects of intrathecal CTOP (0.01 ng), CTAP (0.001 ng) and naltrindole (NTI; 0.01 ng) on established morphine tolerance in the tail-flick test. Tolerance was induced by single daily intrathecal injection of morphine (Mor; 15 μg) for 5 days. On day 6, morphine was administered with CTOP, CTAP or NTI as single injection until day 10. Nociceptive testing was performed 60 min after each injection. The data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. for four to five animals. (b) Cumulative dose–response curves for the antinociceptive effects of acute morphine in the treatment groups represented in (a). The dose–response curves were obtained 24 h after termination of the chronic drug treatment. Ascending doses of intrathecal morphine were given every 30 min and the antinocieptive response was measured in the tail-flick test 25 min after each injection. Significant differences from the action of morphine alone: *P<0.01, **P<0.001. CTAP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; CTOP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; NTI, naltrindole.

Similar results were obtained in the paw-pressure test (Figure 6). In both the CTAP–morphine and naltrindole–morphine groups, the antinociceptive response recovered to 60% of the maximal value (Figure 6a). Administration of CTAP or naltrindole alone to morphine tolerant animals also produced a weak antinociceptive response, reaching 20% of the maximal value. The cumulative dose–response curves to acute morphine in the paw-pressure test (Figure 6b) showed a similar pattern as those observed in the tail-flick test.

Figure 6.

Effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on established morphine tolerance in the paw-pressure test. (a) Time course of the effects of intrathecal CTOP (0.01 ng), CTAP (0.001 ng) and naltrindole (NTI; 0.01 ng) on established morphine tolerance in the paw-pressure test. Tolerance was induced by single daily intrathecal injection of morphine (Mor; 15 μg) for 5 days. On day 6, morphine was administered with CTOP, CTAP or NTI as single injection until day 10. Nociceptive testing was performed 60 min after each injection. The data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. for four to five animals. (b) Cumulative dose–response curves for the antinociceptive effects of acute morphine in the treatment groups represented in (a). The dose–response curves were obtained 24 h after termination of the chronic drug treatment. Ascending doses of intrathecal morphine were given every 30 min and the antinocieptive response was measured in the paw-pressure test 25 min after each injection. Significant differences from the action of morphine alone: *P<0.01, **P<0.001. CTAP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; CTOP, D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2; NTI, naltrindole.

The morphine ED50 values obtained from the dose–response curves depicted in Figures 5b and 6bc are represented in Table 2. The ED50 values in the group treated with intrathecal morphine for 10 days showed a nearly eightfold increase over the value in the control group treated with saline. This increase was completely abolished in the groups that had received morphine in combination with low doses of CTAP or naltrindole from day 6 to 10. The ED50 values in the group that had received CTAP or naltrindole alone from day 6 to 10 were comparable to the values in the control group. Thus, low doses of the opioid antagonists effectively reversed the loss of agonist potency in animals rendered tolerant to intrathecal morphine.

Table 2.

The effects of ultralow doses of opioid receptor antagonists on the reversal of tolerance to intrathecal morphine

|

Chronic treatment (10 days) |

ED50 (mean±s.e.m.) (mg) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Days 1–5 | Days 6–10 | Tail flick | Paw pressure |

| Saline | Saline | 5.1±0.3 | 6.4±0.3 |

| Morphine (15 μg) | Morphine (15 μg) | 43.5±1.2a | 57.9±1.2a |

| Morphine (15 μg) | Morphine/CTAP (0.001 ng) | 4.9±0.2 | 8.8±1.6 |

| Morphine (15 μg) | Morphine/naltrindole (0.01 ng) | 3.7±0.1 | 5.6±0.5 |

| Morphine (15 μg) | Saline | 7.3±0.3 | 18.1±3.9 |

| Morphine (15 μg) | CTAP (0.001 ng) | 6.8±0.6 | 6.7±0.8 |

| Morphine (15 μg) | Naltrindole (0.01 ng) | 5.2±0.8 | 10.0±0.7 |

Following the end of the 10-day chronic treatment period, cumulative dose–response curves to acute morphine were generated on day 11, and ED50 values for morphine were derived from these curves.

Significant differences from saline group (P<0.001).

Discussion and conclusions

A previous study showed that ultralow doses of the opioid receptor antagonist, naltrexone, paradoxically augmented acute spinal morphine antinociception and inhibited the development of chronic morphine tolerance or reversed this phenomenon (Powell et al., 2002). As naltrexone is a nonselective opioid antagonist, and the development of tolerance to morphine involves the activity of μ as well as δ opioid receptors (see Introduction), this study examined the effects of low doses of antagonists selective for μ (CTOP and CTAP) or δ (naltrindole) opioid receptors on the acute and chronic effects of spinal morphine. The results showed that both classes of antagonists, at doses well below those producing a blockade of μ or δ receptor-mediated analgesia (Malmberg and Yaksh, 1992; Gouarderes et al., 1996; Chen and Pan, 2006), markedly increased acute morphine effects in both the tail-flick and paw-pressure test and inhibited or reversed the loss of agonist potency associated with chronic tolerance. Surprisingly, the administration of antagonists alone to tolerant animals produced a weak antinociceptive effect in both tests over the 5-day treatment period. This effect, not seen previously with naltrexone (Powell et al., 2002), was probably revealed in this study by a delayed measurement of the drug-induced response. It is unlikely that this response resulted from antagonist effects on residual morphine in the intrathecal space, since it was observed on successive days after termination of agonist delivery. While this response could reflect a facilitatory action of antagonists on an endogenous opioid, possibly mobilized by repeated nociceptive testing and/or drug injections, it was not observed in the tolerance induction tests that also involved these procedures. The basis of its origin remains to be investigated in future work.

The actions of μ-receptor antagonists, CTOP or CTAP, on morphine analgesia and tolerance could be interpreted in terms of the bimodal opioid receptor model proposed by Crain and Shen (1995, 2000) on the basis of studies on DRG neurons. A key aspect of this model is that morphine exerts a latent stimulatory action that opposes the classical inhibitory effect of the agonist and thus limits its analgesic potential. At the cellular level, the stimulatory action is attributed to agonist activation of a Gs-coupled mode of the bimodal receptor, which is sensitive to ultralow doses of opioid antagonists. According to Crain and Shen (1998), the latent activation of Gs-coupled receptors by chronic morphine results from an increase in GM1 ganglioside, facilitating the conversion of opioid receptors from a Gi- to a Gs-coupled mode. Tolerance is viewed as a sensitization to the stimulatory action and the induction of a cellular cascade – activation of adenylyl cyclase, elevation of cAMP levels, mobilization of nociceptive sensory transmitters, and stimulation of their receptors – that induces a progressive and latent behavioural hyperalgesia, which physiologically antagonizes the analgesic response to the agonist. Blockade of the stimulatory action by low doses of antagonists could prevent this cascade and thus permit unhindered expression of the Gi-coupled inhibitory receptor mode and a sustained analgesic response. A recent study by Wang et al. (2005) provides support for this model by showing that chronic treatment with systemic morphine in rats promotes Gs coupling of the μ opioid receptor in the spinal cord and certain brain regions, a response that coincides with a Gβγ-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase types II and IV. These biochemical responses are prevented by treatment with an ultralow dose of naloxone blocking the development of analgesic tolerance. Thus, by producing a blockade of the stimulatory effect of morphine on spinal nociceptive neurons, the low dose of CTOP or CTAP may have prevented the induction of hyperalgesia that limits the analgesic potential of the agonist. Indeed, administration of a low dose of systemic morphine to mice elicits a thermal hyperalgesia that is sensitive to ultralow doses of naloxone (Crain and Shen, 2001), and chronic infusions of spinal morphine produce a behavioural hyperalgesia that becomes manifest during agonist delivery (Mao et al., 1994; Gardell et al., 2002). Although the chronic morphine injections in the present study did not produce a discernable hyperalgesia, we have observed that a very low dose of acute spinal morphine in rats produces a sustained tail-flick hyperalgesia that is blocked by ultralow doses of opioid antagonists (McNaull et al., 2007). In the current study, however, the morphine-induced hyperalgesia could have remained latent and impaired the full expression of agonist-induced analgesic effects. Indeed, the chronic morphine treatment paradigm used here has been found to increase the expression of both CGRP and substance P in the rat dorsal horn, and pharmacological blockade of their respective receptors has been shown to attenuate or reverse tolerance to spinal morphine (Powell et al., 2000, 2003). Our preliminary studies have shown that the low doses of the opioid antagonists used in this study can block the morphine-induced increase in the expression of spinal CGRP (Prupas et al., 2006).

Interestingly, a low dose of naltrindole faithfully replicated the actions of the two μ-receptor antagonists on acute and chronic morphine effects, suggesting a role for δ opioid receptors in processes limiting morphine analgesia. The possibility that the naltrindole effects resulted from a nonselective action on the excitatory mode of the μ receptor (see above) cannot be excluded; however, the dose of naltrindole used here was extremely low and thus it is likely to have retained a preference for the δ receptor. Nevertheless, a crossover effect of naltrindole on the excitatory μ receptor would have plausibility if this entity represented a μ–δ receptor complex localized on spinal sensory neurons. The morphine effect on such a receptor complex would be sensitive to ultralow doses of both types of receptor antagonist. The validity of this notion is strengthened by several observations. The expression of μ and δ receptor complexes in vitro produces qualitative and quantitative changes in ligand-binding and receptor-signalling properties that differ from those of individual receptors (George et al., 2000). In cells expressing the μ–δ receptor complex, very low doses of a δ-receptor antagonist have been found to augment both the potency and efficacy of μ receptor signalling and vice versa (Gomes et al., 2000, 2004). These findings have led to the proposal that the combination of μ and δ receptor ligands produces a change in the conformational state of μ–δ receptor complexes, which alters receptor pharmacology (Gomes et al., 2004). Anatomical studies have established the colocalization of μ and δ receptors in the rat spinal cord and indeed on the same dorsal horn neuron (Arvidsson et al., 1995; Cheng et al., 1996). Lastly, in the cultured DRG neuron model, ultralow doses of μ as well as δ receptor agonists exert a stimulatory effect that is blocked by similar doses of their respective antagonists (Crain and Shen, 1990). Thus, if the excitatory action of morphine, limiting its acute analgesic effects and contributing to the development of tolerance, were mediated by a μ–δ receptor complex localized on spinal nociceptive sensory neurons, this action would be sensitive to low doses of a μ antagonist such as CTAP as well as a δ antagonist such as naltrindole. However, it remains to be determined if μ and δ receptors associated with spinal sensory neurons (Cheng et al., 1996) exist as a complex and, importantly, whether they signal an excitatory response when activated by selective agonists.

An alternate explanation for the paradoxical effects of the opioid antagonists observed here is that these may be mediated by certain endogenous modulators of opioid activity implicated in the genesis of opioid tolerance (Rothman, 1992). Among these, amidated neuropeptides, typified by the octapeptide, neuropeptide FF (NPFF), are of interest as they share the pro-opioid and antitolerance effects of ultralow doses of the competitive opioid receptor antagonists in the spinal analgesia model. These peptides are known to activate Gi-coupled NPFF receptors, whose anatomical distribution and signalling properties are similar to those of opioid receptors (Allard et al., 1992; Bonini et al., 2000). Although designated as functional antagonists of opioid activity, largely on the basis of their supraspinal anti-opioid effects (Roumy and Zajac, 1998), low intrathecal doses of NPFF and related neuropeptides have been found to increase morphine analgesia (Gouarderes et al., 1993) and to restore agonist potency in animals rendered tolerant to spinal morphine (Jhamandas et al., 2006b). Thus, low doses of the competitive opioid receptor antagonists could exert their pro-opioid actions by mobilizing these novel endogenous peptides. However, this possibility remains to be investigated in future experiments.

Although it would be useful to conduct experiments to determine the specificity of opioid receptor antagonist actions by comparisons with non-opioid receptor antagonists, the interpretation of results yielded by such experiments may be complicated by direct or indirect interactions between opioid and non-opioid receptors. Direct interactions may result from the activity of heteromeric receptor complexes such as those between μ opioid receptors and α2 adrenoceptors (Jordan et al., 2003) or cannabinoid CB1 receptors (Rios et al., 2006) that are localized on nociceptive sensory neurons and that elicit antinociception. In such complexes, the responses elicited by the activity of one receptor can be modified by ligands acting at the other receptor unit. Indeed, Aley and Levine (1997) have demonstrated that the antinociception, tolerance and withdrawal hyperalgesia resulting from opioid agonist action on peripheral nociceptors can be influenced by an α2-receptor antagonist and vice versa. They have proposed that these responses are produced via a receptor complex and involve common mechanisms. Our recent investigations in the spinal model used in the current study demonstrate that morphine antinociception or tolerance can be influenced by α2 or cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists (Jhamandas et al., 2006a; Trang et al., 2007). Indirect interactions may occur as a result of altered function of non-opioid receptors due to opioid-induced changes in the sensory transmitters that target these receptors. Chronic exposure to morphine increases the expression of the sensory neuropeptides substance P and CGRP, and the resultant activity of NK1 and CGRP receptors contributes to the genesis of analgesic tolerance, as indicated by the ability of antagonists of these receptors to block or reverse this tolerance (Powell et al., 2000, 2003). In view of the complex interplay between opioid and non-opioid receptors or opioid-induced changes in the function of non-opioid receptors, determining the specificity of atypical opioid antagonist actions remains a challenging task. However, we have recently observed that the antinociception produced by morphine alone or in combination with ultralow doses of opioid antagonists has a common purinergic basis (McNaull et al., 2007).

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the administration of μ- as well as δ-opioid receptor antagonists, at doses significantly lower than those known to produce receptor blockade, can augment the analgesic response to spinal morphine, inhibit the development of chronic analgesic tolerance and reverse this tolerance. The use of ultralow doses of opioid antagonists may have potential applicability in the optimization of analgesic effects of opioid drugs for the clinical control of pain.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge grant support to KJ from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). NSA was supported by a National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) scholarship. An abstract of this work was presented at the 31st Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, November 10–15, 2001, San Diego, CA, USA.

Abbreviations

- CTAP

D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2

- CTOP

D-Phe-Cys-Tyr-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- MPE

maximum percent effect

- NPFF

neuropeptide FF

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Aley KO, Levine JD. Multiple receptors involved in peripheral alpha 2, mu, and A1 antinociception, tolerance, and withdrawal. J Neurosci. 1997;17:735–744. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00735.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard M, Zajac JM, Simonnet G. Autoradiographic distribution of receptors to FLFQPQRFamide, a morphine-modulating peptide, in rat central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1992;49:101–116. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90078-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Chakrabarti S, Lee JH, Nakano AH, Dado RJ, et al. Distribution and targeting of a mu-opioid receptor (MOR1) in brain and spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1995;15:3328–3341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-03328.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CP, Smith FL, Kelly E, Dewey WL, Henderson G. How important is protein kinase C in mu-opioid receptor desensitization and morphine tolerance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:558–565. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini JA, Jones KA, Adham N, Forray C, Artymyshyn R, Durkin MM, et al. Identification and characterization of two G protein-coupled receptors for neuropeptide FF. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:39324–39331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti S, Oppermann M, Gintzler AR. Chronic morphine induces the concomitant phosphorylation and altered association of multiple signaling proteins: a novel mechanism for modulating cell signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4209–4214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071031798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Huang LY. Sustained potentiation of NMDA receptor-mediated glutamate responses through activation of protein kinase C by a μ opioid. Neuron. 1991;7:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90270-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SR, Pan HL. Blocking μ opioid receptors in the spinal cord prevents the analgesic action by subsequent systemic opioids. Brain Res. 2006;1081:119–125. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng PY, Moriwaki A, Wang JB, Uhl GR, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural localization of mu-opioid receptors in the superficial layers of the rat cervical spinal cord: extrasynaptic localization and proximity to Leu5-enkephalin. Brain Res. 1996;731:141–154. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00492-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain SM, Shen KF. Opioids can evoke direct receptor-mediated excitatory effects on sensory neurons. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1990;11:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90322-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain SM, Shen KF. Ultra-low concentrations of naloxone selectively antagonize excitatory effects of morphine on sensory neurons, thereby increasing its antinociceptive potency and attenuating tolerance/dependence during chronic cotreatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10540–10544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain SM, Shen KF. GM1 ganglioside-induced modulation of opioid receptor-mediated functions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;845:106–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain SM, Shen KF. Antagonists of excitatory opioid receptor functions enhance morphine's analgesic potency and attenuate opioid tolerance/dependence liability. Pain. 2000;84:121–131. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain SM, Shen KF. Acute thermal hyperalgesia elicited by low-dose morphine in normal mice is blocked by ultra-low-dose naltrexone, unmasking potent opioid analgesia. Brain Res. 2001;888:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickenson AH, Sullivan AF. Electrophysiological studies on the effects of intrathecal morphine on nociceptive neurones in the rat dorsal horn. Pain. 1986;24:211–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar S, Yaksh TL. Concurrent spinal infusion of MK801 blocks spinal tolerance and dependence induced by chronic intrathecal morphine in the rat. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:1177–1188. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199605000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fundytus ME, Schiller PW, Shapiro M, Weltrowska G, Coderre TJ. Attenuation of morphine tolerance and dependence with the highly selective delta-opioid receptor antagonist TIPP[psi] Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;286:105–108. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00554-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardell LR, Wang R, Burgess SE, Ossipov MH, Vanderah TW, Malan TP, Jr, et al. Sustained morphine exposure induces a spinal dynorphin-dependent enhancement of excitatory transmitter release from primary afferent fibers. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6747–6755. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06747.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SR, Fan T, Xie Z, Tse R, Tam V, Varghese G, et al. Oligomerization of mu- and delta-opioid receptors. Generation of novel functional properties. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26128–26135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000345200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes I, Gupta A, Filipovska J, Szeto HH, Pintar JE, Devi LA. A role for heterodimerization of μ and δ opiate receptors in enhancing morphine analgesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5135–5139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307601101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes I, Jordan BA, Gupta A, Trapaidze N, Nagy V, Devi LA. Heterodimerization of μ and δ opioid receptors: a role in opiate synergy. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-j0007.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouarderes C, Jhamandas K, Sutak M, Zajac JM. Role of opioid receptors in the spinal antinociceptive effects of neuropeptide FF analogues. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:493–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouarderes C, Sutak M, Zajac JM, Jhamandas K. Antinociceptive effects of intrathecally administered F8Famide and FMRFamide in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;237:73–81. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90095-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamann SR, Malik H, Sloan JW, Wala EP. Interactions of ‘ultra-low' doses of naltrexone and morphine in mature and young male and female rats. Receptors Channels. 2004;10:73–81. doi: 10.1080/10606820490464334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Fong J, von Zastrow M, Whistler JL. Regulation of opioid receptor trafficking and morphine tolerance by receptor oligomerization. Cell. 2002;108:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhamandas K, Milne B, Sutak M, Cahill CM.Ultra-low doses of the alpha 2 receptor antagonist atipamezole augment spinal opioid analgesia and inhibit tolerance 2006a. Program No. 643.2. 2006 Neuroscience Meeting Planner, Atlanta, GA: Society for Neuroscience, 2006. Online

- Jhamandas K, Milne B, Sutak M, Gouarderes C, Zajac JM, Yang HY. Facilitation of spinal morphine analgesia in normal and morphine tolerant animals by neuropeptide SF and related peptides. Peptides. 2006b;27:953–963. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan BA, Gomes I, Rios C, Filipovska J, Devi LA. Functional interactions between μ opioid and alpha 2A-adrenergic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1317–1324. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg AB, Yaksh TL. Isobolographic and dose–response analyses of the interaction between intrathecal μ and δ agonists: effects of naltrindole and its benzofuran analog (NTB) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;263:264–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Price DD, Mayer DJ. Thermal hyperalgesia in association with the development of morphine tolerance in rats: roles of excitatory amino acid receptors and protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2301–2312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02301.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Price DD, Mayer DJ. Mechanisms of hyperalgesia and morphine tolerance: a current view of their possible interactions. Pain. 1995;62:259–274. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Sung B, Ji RR, Lim G. Chronic morphine induces downregulation of spinal glutamate transporters: implications in morphine tolerance and abnormal pain sensitivity. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8312–8323. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08312.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaull B, Trang T, Sutak M, Jhamandas A. Inhibition of tolerance to spinal morphine antinociception by low doses of opioid receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;560:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard DP, van Rossum D, Kar S, St Pierre S, Sutak M, Jhamandas K, et al. A calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist prevents the development of tolerance to spinal morphine analgesia. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2342–2351. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-07-02342.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossipov MH, Lai J, Vanderah TW, Porreca F. Induction of pain facilitation by sustained opioid exposure: relationship to opioid antinociceptive tolerance. Life Sci. 2003;73:783–800. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KJ, Abul-Husn NS, Jhamandas A, Olmstead MC, Beninger RJ, Jhamandas K. Paradoxical effects of the opioid antagonist naltrexone on morphine analgesia, tolerance, and reward in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:588–596. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.2.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KJ, Hosokawa A, Bell A, Sutak M, Milne B, Quirion R, et al. Comparative effects of cyclo-oxygenase and nitric oxide synthase inhibition on the development and reversal of spinal opioid tolerance. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:631–644. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KJ, Ma W, Sutak M, Doods H, Quirion R, Jhamandas K. Blockade and reversal of spinal morphine tolerance by peptide and non-peptide calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:875–884. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell KJ, Quirion R, Jhamandas K. Inhibition of neurokinin-1-substance P receptor and prostanoid activity prevents and reverses the development of morphine tolerance in vivo and the morphine-induced increase in CGRP expression in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1572–1583. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prupas GM, Cahill CM, Jhamandas K.Ultra-low doses of μ and delta-opioid receptor antagonists inhibit and reverse the upregulation of pronociceptive transmitters associated with morphine tolerance 2006. Program No. 643.1. 2006 Neuroscience Meeting Planner, Atlanta, GA: Society for Neuroscience, 2006. Online

- Raghavendra V, Rutkowski MD, DeLeo JA. The role of spinal neuroimmune activation in morphine tolerance/hyperalgesia in neuropathic and sham-operated rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9980–9989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-22-09980.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios C, Gomes I, Devi LA. opioid and CB1 cannabinoid receptor interactions: reciprocal inhibition of receptor signaling and neuritogenesis. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:387–395. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman RB. A review of the role of anti-opioid peptides in morphine tolerance and dependence. Synapse. 1992;12:129–138. doi: 10.1002/syn.890120206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumy M, Zajac JM. Neuropeptide FF, pain and analgesia. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;345:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01604-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terner JM, Barrett AC, Lomas LM, Negus SS, Picker MJ. Influence of low doses of naltrexone on morphine antinociception and morphine tolerance in male and female rats of four strains. Pain. 2006;122:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trang T, Quirion R, Jhamandas K. The spinal basis of opioid tolerance and physical dependence: involvement of calcitonin gene-related peptide, substance P, and arachidonic acid-derived metabolites. Peptides. 2005;26:1346–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trang T, Sutak M, Jhamandas K.Involvement of cannabinoid (CB1)-receptors in the development and maintenance of opioid tolerance Neuroscience 2007 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.02.031doi [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vanderah TW, Gardell LR, Burgess SE, Ibrahim M, Dogrul A, Zhong CM, et al. Dynorphin promotes abnormal pain and spinal opioid antinociceptive tolerance. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7074–7079. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-07074.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY, Friedman E, Olmstead MC, Burns LH. Ultra-low-dose naloxone suppresses opioid tolerance, dependence and associated changes in μ opioid receptor-G protein coupling and Gbetagamma signaling. Neuroscience. 2005;135:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werz MA, Macdonald RL. Opioid peptides with differential affinity for μ and δ receptors decrease sensory neuron calcium-dependent action potentials. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;227:394–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Chronic catheterization of the spinal subarachnoid space. Physiol Behav. 1976;17:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(76)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, King MA, Schuller AG, Nitsche JF, Reidl M, Elde RP, et al. Retention of supraspinal delta-like analgesia and loss of morphine tolerance in δ opioid receptor knockout mice. Neuron. 1999;24:243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80836-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]