Abstract

Aim

To investigate the in vivo effect of treatment with tolterodine on debrisoquine 4-hydroxylation (an index of CYP2D6 activity), omeprazole 5-hydroxylation (CYP2C19), omeprazole sulphoxidation (CYP3A4) and caffeine N3-demethylation (CYP1A2).

Methods

Twelve healthy male volunteers (eight extensive metabolisers [EMs] and four poor metabolisers [PMs] with respect to CYP2D6) received 4 mg tolterodine l-tartrate orally twice daily for 6 days. All subjects were EMs with respect to CYP2C19. The subjects received single oral doses of debrisoquine (10 mg), omeprazole (20 mg) and caffeine (100 mg) for determination of the appropriate metabolic ratios (MR). The drugs were given on separate consecutive days, before, during and after the co-administration of tolterodine.

Results

Mean serum tolterodine concentrations were 5–10 times higher in PMs than in EMs. Serum concentrations of the active 5-hydroxymethyl metabolite of tolterodine, 5-HM, were not quantifiable in PMs. The mean MR of debrisoquine (95% confidence interval) during tolterodine treatment was 0.50 (0.25–0.99) and did not differ statistically from the values before [0.49 (0.20–1.2)] and after tolterodine administration [0.46 (0.14–1.6)] in EMs. The mean MR of omeprazole hydroxylation and sulphoxidation or caffeine metabolism were not changed in the presence of tolterodine in either EMs or PMs. Debrisoquine and caffeine had no significant effect on the AUC(1,3 h) of either tolterodine or 5-HM, but during omeprazole administration small decreases (13–19%) in these parameters were seen.

Conclusions

Tolterodine, administered at twice the expected therapeutic dosage, did not change the disposition of the probe drugs debrisoquine, omeprazole and caffeine and thus had no detectable effect on the activities of CYPs 2D6, 2C19, 3A4 and 1A2. Alteration of the metabolism of substrates of these enzymes by tolterodine is unlikely to occur.

Keywords: antimuscarinic, tolterodine, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP1A2, overactive bladder, polymorphism

Introduction

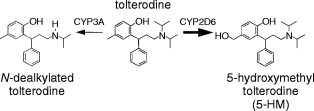

Tolterodine is a new antimuscarinic drug for the treatment of patients with overactive bladder, presenting with urinary frequency, urgency and urge incontinence [1–3]. In vitro, tolterodine exhibits high affinity and specificity for muscarinic receptors and shows a selectivity for the urinary bladder over the salivary glands in vivo [4]. In humans, tolterodine is rapidly absorbed, exhibits high first-pass extraction and the systemically available drug is eliminated mainly by metabolism [5]. Two different oxidative metabolic pathways, hydroxylation and N-dealkylation, have been identified in man (Figure 1) [5]. Hydroxylation to the pharmacologically active 5-hydroxymethyl metabolite (5-HM; PNU-200577) is catalysed by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 [6, 7], while the N-dealkylation pathway is catalysed by CYP3A [7]. Preclinical studies have shown that 5-HM is equipotent to tolterodine in vitro and has similar functional bladder selectivity in vivo [8].

Figure 1.

Tolterodine [(R)-N,N-diisopropyl-3-(2-hydroxy-5-methylphenyl)-3-phenylpropanamine] and its primary metabolites. The thicker arrow shows the main metabolic pathway in EMs of debrisoquine.

Since CYP2D6 is polymorphically distributed and mediates the major metabolic pathway for tolterodine metabolism, subjects can be clearly identified pharmacokinetically as poor (PMs) or extensive metabolisers (EMs) of the drug. In EMs of debrisoquine, the mean systemic clearance of tolterodine is 44 l h−1 yielding an elimination half-life of 2–3 h [6]. By contrast clearance is five times lower in PMs, who have a mean half-life of 9 h. This results in a seven-fold higher maximum serum concentration of tolterodine at steady-state in PMs compared with EMs. Serum levels of 5-HM are similar to those of tolterodine in EMs, but are not quantifiable in PMs [6]. However, it has been demonstrated that the large difference in pharmacokinetics between EMs and PMs is of minor importance for the antimuscarinic effect of tolterodine. The combined action of parent drug and active metabolite in combination with a 10-fold difference in protein binding between tolterodine and 5-HM results in similar exposure to pharmacologically active species in both phenotypes [6, 9].

Hepatic metabolism by CYP enzymes is a major determinant in the elimination of many drugs. Thus, inhibition of enzyme activity that may occur during combined drug therapy is of serious clinical concern. The major isoforms of CYP involved in human drug metabolism are CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2C9 CYP2C19, CYP1A2 and CYP2E1 [10]. Of these, CYP2D6, CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 are polymorphically distributed. Drugs which are selective substrates of specificCYP isoforms can be used as in vivo probes to determine enzyme activity in individual subjects. Because tolterodine is a good substrate for both CYP2D6 and CYP3A, it follows that significant inhibition of the activities of these isoforms by the drug may occur in vivo.

The objective of this study was to investigate the in vivo effect of treatment with tolterodine, administered at twice the therapeutic dosage, on debrisoquine hydroxylation (an index of CYP2D6 activity), omeprazole hydroxylation (CYP2C19), omeprazole sulphoxidation (CYP3A4) and caffeine metabolism (CYP1A2) in healthy volunteers.

Methods

Subjects

Twelve healthy male volunteers (mean age 30±5 years) were included in this open, non-randomised, crossover study. All subjects had been previously phenotyped with debrisoquine and mephenytoin [11]. Eight subjects were EMs of debrisoquine (urinary metabolic ratio [MR] <1.0) and four were PMs (MR>12.6). In order to ensure large differences in CYP2D6 activity between the panels, only EMs with a MR of less than 1.0 were included. All subjects were EMs of mephenytoin (urinary S/R ratio < 0.8). The study was approved by the ethics committee at the Huddinge University Hospital and each volunteer gave written informed consent before the study. Smoking and intake of alcohol or xanthine-containing beverages during the study period were not allowed. Recent intake of substances known to inhibit or induce drug metabolising CYP enzymes was not permitted.

Drug administration

Each volunteer was given the probe drugs, debrisoquine (Declinax; 10 mg, Roche), caffeine (Koffein; 100 mg, ACO) and omeprazole (Losec; 20 mg, Astra Hässle), as single-doses on 3 consecutive and separate days, and immediately before tolterodine administration. Oral doses of tolterodine l-tartrate (Pharmacia & Upjohn), 4 mg twice daily, were given for 6 days by which time serum concentrations had reached steady state. One hour after the tolterodine dose, debrisoquine (Day 4), caffeine (Day 5) and omeprazole (Day 6) were again administered as single-doses. The time difference between drug administration was chosen to ensure high systemic exposure of tolterodine to CYP enzymes. Four days after the last tolterodine dose the probe drugs were given consecutively on three separate days and in the same order as previously. Venous blood samples were drawn at 1, 2 and 3 h after tolterodine administration on days 3, 4, 5 and 6 for serum tolterodine and 5-HM quantification. Additional blood samples for the determination of omeprazole plasma concentrations and those of its hydroxy and sulphone metabolites were obtained at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 h after omeprazole administration. All urine was collected over the periods 0-8 and 0-24 h after administration of debrisoquine and caffeine, respectively, for quantification of the parent compound and metabolites.

Assay procedures

The determination of tolterodine and 5-HM concentrations in serum was performed using a capillary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry assay [12]. The limit of quantification (LOQ) was 0.90 nm with an accuracy for both analytes from 94% to 103% and a precision from 3.3% to 14%. The measurement of debrisoquine and 4-hydroxydebrisoquine in urine was performed using gas chromatography with nitrogen-selective detection 13]. The LOQ was 20 μm with an accuracy for both analytes from 90% to 115% and a precision from 3.2% to 12%. Omeprazole and its hydroxy and sulphone metabolites in plasma were assayed using high performance liquid chromatography and u.v. detection [14]. The LOQ was 30 nm to 50 nm with an accuracy for the three analytes from 95% to 110% and a precision from 4.0% to 10%. The determination of caffeine and its metabolites in urine was performed using high performance liquid chromatography and u.v. detection [15]. The LOQ was approximately 1.5 μm with an accuracy for all analytes from 91% to 114% and a precision from 1.8% to 13%.

Data analysis

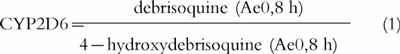

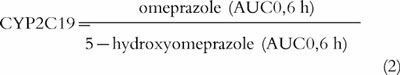

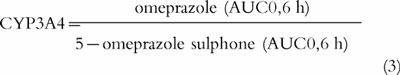

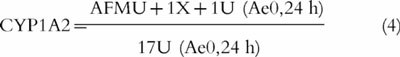

The amount excreted in urine (Ae) of debrisoquine, 4-hydroxydebrisoquine, caffeine and caffeine metabolites was measured directly. The areas under the plasma (omeprazole, hydroxyomeprazole and omeprazole sulphone) and the serum (tolterodine and 5-HM) concentration-time curves (AUC) were calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule [16] [PCNonlin (Version 4.2)] [17]. The following MRs for debrisoquine hydroxylation [18], omeprazole hydroxylation [19], omeprazole sulphoxidation [20], and caffeine metabolism [21] were used as indices of the respective CYP isoform activity:

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

|

4 |

where AFMU = 5-acetylamino-6-formylamino-3-methyluracil; 1U = 1-methyl uric acid; 1X = 1-methylxanthine; and 17U = 1,7-dimethyl uric acid. Caffeine metabolism can also be used as a measure of N-acetyl transferase (NAT2) activity with the following metabolic ratio:

|

5 |

The data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), with subsequent post hoc comparisons of individual mean values using the PROC GLM part of the SAS®-package. Differences were considered to be significant if P was < 0.05.

Results

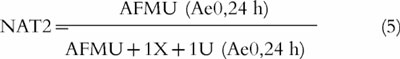

The individual serum concentration-time profiles of tolterodine and 5-HM during the first 3 h following oral administration on days 3 (baseline), 4, 5 and 6 are shown in Figure 2. There was a clear difference between the two CYP2D6 phenotypes, with the mean concentrations of tolterodine being 5–10 times higher in PMs compared with those in EMs. Serum 5-HM concentrations were in the same range as the parent compound in EMs and were not quantifiable in the PM panel.

Figure 2.

Steady-state serum concentration-time profiles (taken 1, 2 and 3 h after administration) of (a) tolterodine (4 mg twice daily for 6 days) and (b) 5-hydroxymethyltolterodine (5-HM) in eight extensive (—) and four poor metabolisers (•) of debrisoquine after single oral doses of debrisoquine, caffeine and omeprazole (given 1 h after tolterodine).

Debrisoquine and caffeine had no significant effect on AUC(1,3 h) values for either tolterodine or 5-HM. In contrast, tolterodine AUC(1,3 h) decreased significantly in both EMs (−19%) and PMs (−13%) (P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively) during omeprazole administration. There was a corresponding reduction in the AUC(1,3 h) for 5-HM in the EM panel (−19%; P < 0.01).

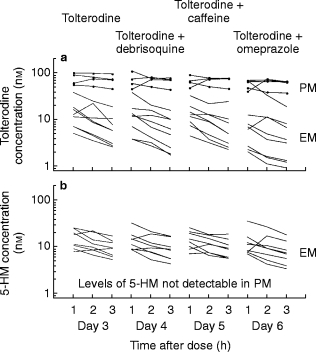

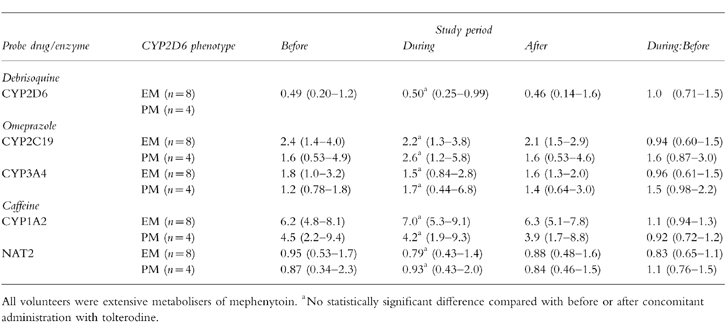

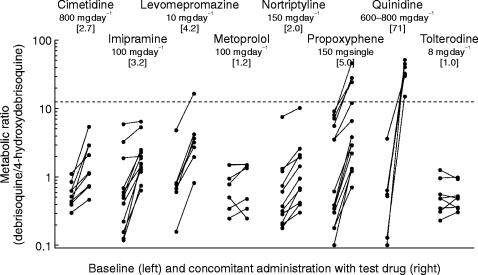

The MRs of debrisoquine, omeprazole and caffeine before, during and after co-administration of tolterodine are summarised according to phenotype in Table 1 and Figure 3. No significant change in any of the MRs of the probe drugs was seen after tolterodine administration.

Table 1.

Geometric mean and 95% CI (within brackets) of the metabolic ratios of debrisoquine, omeprazole and caffeine before, during and after co-administration of tolterodine (4 mg twice daily for 6 days) in 12 healthy volunteers. The ratios of values during to before are also presented.

Figure 3.

The effect of various drugs on the debrisoquine metabolic ratio, an index of CYP2D6 activity. The cimetidine data are adapted with permission from Philip et al. [21], those for imipramine from Brøsen et al. [22], those for levomepromazine and metoprolol from Kallio et al. [23], those for nortriptyline from Nordin et al. [24], those for propoxyphene from Sanz & Bertilsson [25], those for quinidine from Brøsen et al. [26] and those for tolterodine from the present study. The geometric mean value obtained during concomitant administration (drug and debrisoquine) divided by the corresponding value in the absence of drug (debrisoquine alone) is given in brackets under the daily dose of each drug.

Discussion

This study confirms earlier observations that tolterodine is extensively metabolised to 5-HM by CYP2D6, since this metabolite was undetectable in PMs [6]. Previously, it was demonstrated that at least 80% of the systemic clearance of tolterodine in EMs was related to CYP2D6 activity [6]. However, the present study clearly demonstrates that tolterodine, administered at twice the therapeutic dosage, does not affect CYP2D6 activity based on the MR of debrisoquine. Thus, it is almost certain that tolterodine will have little effect on the disposition of drugs metabolised by CYP2D6.

In order to assess the likelihood that the metabolism of tolterodine itself may be inhibited by other drugs, the effect of various substrates and inhibitors of CYP2D6 activity on the debrisoquine MR was reviewed (Figure 3). Quinidine being such a potent inhibitor of CYP2D6 has been shown to convert all EMs into functional PMs [27]. Relatively low daily doses of the neuroleptic levomepromazine (75–225 mg day−1) and the analgesic d-propoxyphene (300 mg day−1) caused less inhibition than did quinidine [24, 26]. However, at normal therapeutic daily doses the extent of inhibition by these drugs is likely to be similar to that of quinidine. Cimetidine, a mixed CYP1A2, 2C9 and 2D6 inhibitor [22], as well as the antidepressants imipramine [23] and nortriptyline [25], inhibited the CYP2D6 activity significantly but not as markedly as the drugs mentioned previously. Thus, the metabolism of tolterodine is likely to be affected (to a variable extent) by CYP2D6 inhibitors, which is supported by a recently performed study of the effect of fluoxetine, a potent CYP2D6 inhibitor [28], on the disposition of tolterodine. Fluoxetine caused significant inhibition of the metabolism of tolterodine, resulting in an approximately 5-fold increase in its AUC among EMs [29].

The present study shows no evidence that tolterodine inhibits omeprazole hydroxylation. Furthermore, no interaction was seen in a recent study of the effect of tolterodine on the metabolism of warfarin (Rahimy, personal communication). S-warfarin is mainly metabolised by another CYP2C isoenzyme (CYP2C9) and has been suggested as a suitable probe drug for CYP2C9 activity [30]. These findings imply that tolterodine does not interact with CYP2C9.

In a recently performed study, the contribution of CYP3A4 to the clearance of tolterodine in PMs of debrisoquine was evaluated. Ketoconazole, a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 activity [31], decreased the oral clearance of tolterodine by 61% suggesting a major contribution of CYP3A4 to its elimination in PMs [32]. The present study shows that omeprazole sulphoxidation is unaffected in either EMs or PMs during co-administration of tolterodine, making the latter unlikely to interfere with drugs metabolised by CYP3A4. The lower AUC of tolterodine and 5-HM during concomitant administration with omeprazole (Figure 2) may be a spurious finding since a decrease in the concentrations of tolterodine and 5-HM compared to pre-dose values also occurred in the control phase 1 hour after dosing (i.e. at the time in the treatment phase when omeprazole would be administered.

Using caffeine as a probe, fluvoxamine has been identified as a potent inhibitor of CYP1A2 activity [33], moclobemide as a moderately potent inhibitor [34], whereas citalopram, fluoxetine and paroxetine did not affect the activity of this CYP isoform [35]. In the present work tolterodine was also found not to inhibit CYP1A2 activity. This observation is consistent with other work reporting no significant changes in the plasma concentrations of R-warfarin, which is metabolised mainly by CYP1A2 [36], during tolterodine administration (Rahimy, personal communication).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Pharmacia & Upjohn AB, Sweden. We would like to thank C. Alm, E. Götharsson and C. Johansson for their expert assistance, and T. Andersson, T. Villén, G. Tybring and J. A. Carrillo for their analytical expertise in conducting the tolterodine, debrisoquine, omeprazole and caffeine assays.

References

- 1.Rentzhog L, Stanton SL, Cardozo L, Fall M, Nelson E, Abrams P. Efficacy and safety of tolterodine in patients with detrusor instability: a dose ranging study. Br J Urol. 1998;81:42–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jonas U, Höfner K, Madersbacher H, Holmdahl TH and the participants of the international study group. Efficacy and safety of two doses of tolterodine versus placebo in patients with detrusor overactivity and symptoms of frequency, urge incontinence, and urgency: urodynamic evaluation. World J Urol. 1997;15:144–151. doi: 10.1007/BF02201987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Kerrebroeck PE, Amarenco G, Thüroff JW, et al. Dose-ranging study of tolterodine in patients with detrusor hyperreflexia. Neurourol Urodyn. 1998;17:499–512. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(1998)17:5<499::aid-nau6>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nilvebrant L, Andersson K-E, Gillberg P-G, Stahl M, Sparf B. Tolterodine—a new bladder-selective antimuscarinic agent. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;327:195–207. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)89661-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brynne N, Stahl MMS, Hallén B, Edlund PO, Palmér L, Gabrielsson J. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tolterodine in man: a new drug for the treatment of urinary bladder overactivity. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;35:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brynne N, Dalén P, Alván G, Bertilsson L, Gabrielsson J. The influence of CYP2D6 polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics and dynamics of tolterodine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;63:529–539. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Postlind H, Danielson Å, Lindgren A, Andersson SHG. Tolterodine, a new muscarinic receptor antagonist, is metabolized by cytochromes P450 2D6 and 3A in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26:289–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nilvebrant L, Gillberg P-G, Sparf B. Antimuscarinic potency and bladder selectivity of PNU-200577, a major metabolite of tolterodine. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;81:169–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1997.tb02064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gozzi P, Påhlman I. Serum protein binding of tolterodine and its 5-hydroxymetyl metabolite in different species. 6th European Meeting of the Society for the Study of Xenobiotics. 1997 Jun 30–Jul 3; Gothenberg. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyer UA. Overview of enzymes of drug metabolism. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1996;24:449–459. doi: 10.1007/BF02353473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertilsson L, Lou YQ, Du YL, et al. Pronounced differences between native Chinese and Swedish populations in the polymorphic hydroxylations of debrisoquine and S-mephenytoin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;51:388–397. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmér L, Andersson L, Andersson T, Stenberg U. Determination of tolterodine and the 5-hydroxymethyl metabolite in plasma, serum and urine using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 1997;16:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s0731-7085(97)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lennard MS, Silas JH, Smith AJ, Tucker GT. Determination of debrisoquine and its 4-hydroxymetabolite in biologic fluids by gas chromatography with flame-ionization and nitrogen-selective detection. J Chromatogr. 1977;133:161–168. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)89216-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lagerström PO, Persson BA. Determination of omeprazole and metabolites in plasma and urine by liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1984;309:347–356. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(84)80042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrillo JA, Benitez J. Caffeine metabolism in a healthy Spanish population: N-Acetylator phenotype and oxidation pathways. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:293–304. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibaldi M, Perrier D. Pharmacokinetics. Second. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statistical Consultants Inc. PCNonlin and Nonlin84: Software for the statistical analysis of nonlinear models. American Statistician. 1986;40 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahgoub A, Idle JR, Dring LG, Lancaster R, Smith RL. Polymorphic hydroxylation of debrisoquine. Lancet. 1977;ii:584–586.. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang M, Dahl ML, Tybring G, Götharson E, Bertilsson L. Use of omeprazole as a probe for CYP2C19 phenotype in Swedish Caucasians: comparison with S-mephenytoin hydroxylation phenotype and CYP2C19 genotype. Pharmacogenetics. 1995;5:358–363. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199512000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertilsson L, Tybring G, Widén J, Chang M, Tomson T. Carbamazepine treatment induces the CYP3A4 catalysed sulphoxidation of omeprazole, but has no or less effect on hydroxylation via CYP2C19. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;44:186–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rostami-Hodjegan A, Nurminen S, Jackson PR, Tucker GT. Caffeine urinary metabolite ratios as markers of enzyme activity: A theoretical assessment. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:121–149. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199604000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Philip PA, James CA, Rogers HJ. The influence of cimetidine on debrisoquine 4-hydroxylation in extensive metabolisers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;36:319–321. doi: 10.1007/BF00558167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brøsen K, Klysner R, Gram LF, Otton SV, Bech P, Bertilsson L. Steady-state concentrations of imipramine and its metabolites in relation to the sparteine/debrisoquine polymorphism. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;30:679–684. doi: 10.1007/BF00608215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kallio J, Huupponen R, Seppala M, Sako E, Iisalo E. The effects of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists and levomepromazine on the metabolic ratio of debrisoquine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:638–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03827.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nordin C, Siwers B, Benitez J, Bertilsson L. Plasma concentrations of nortriptyline and its 10-hydroxy metabolite in depressed patients-relationship to the debrisoquine hydroxylation metabolic ratio. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1985;19:832–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1985.tb02723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanz EJ, Bertilsson L. d-Propoxyphene is a potent inhibitor of debrisoquine, but not S-mephenytoin 4-hydroxylation in vivo. Ther Drug Monit. 1990;12:297–299. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199005000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brøsen K, Gram LF, Haghfelt T, Bertilsson L. Extensive metabolizers of debrisoquine become poor metabolizers during quinidine treatment. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1987;60:312–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1987.tb01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otton SV, Wu D, Joffe RT, Cheung SW, Sellers EM. Inhibition by fluoxetine of cytochrome P450 2D6 activity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;53:401–409. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brynne N, Apéria B, Åberg-Wistedt A, Hallén B, Bertilsson L. Inhibition of tolterodine metabolism by fluoxetine with minor change in antimuscarinic activity. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rettie AE, Wienkers LC, Gonzalez FJ, Trager WF, Korzekwa KR. Impaired (S)-warfarin metabolism catalysed by the R144C allelic variant of CYP2C9. Pharmacogenetics. 1994;4:39–42. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maurice M, Pichard L, Daujat M, et al. Effects of imidazole derivatives on cytochromes P450 from human hepatocytes in primary culture. FASEB J. 1992;6:752–758. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.2.1371482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brynne N, Forslund C, Hallén B, Gustafsson LL, Bertilsson L. Ketoconazole inhibits the metabolism of tolterodine in subjects with deficient CYP2D6 activity. Exp Toxic Pathol. 1998;50 doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00053.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jeppesen U, Loft S, Poulsen H, Brøsen K. A fluvoxamine-caffeine interaction study. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:213–222. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199606000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gram L, Guentert T, Grange S, Vistisen K, Brøsen K. Moclobemide, a substrate of CYP2C19 and an inhibitor of CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP1A2: A panel study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;55:670–677. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeppesen U, Gram L, Vistisen K, Loft S, Poulsen H, Brøsen K. Dose dependent inhibition of CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 by citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;51:73–78. doi: 10.1007/s002280050163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z, Fasco MJ, Huang Z, Guengerich FP, Kaminsky LS. Human cytochromes P4501A1 and P4501A2: R-warfarin metabolism as a probe. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:1339–1346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]