Abstract

Aims

The purpose of this study was to determine whether human platelet α2-adrenoceptors were altered in essential hypertension. A systematic analysis was carried out on 165 normotensives and 124 untreated primary hypertensives.

Methods

The study was performed at different levels: i) density and affinity of platelet α2-adrenoceptors were determined by receptor binding assays using the full α2-adrenoceptor agonist [3H]-UK 14304 and a thermodynamic analysis of data was carried out to evaluate if binding mechanisms at the molecular level were altered during hypertension; ii) the functionality of Gi proteins coupled to α2-adrenoceptors and iii) forskolin-stimulated cAMP levels were measured.

Results

Platelet α2-adrenoceptors mean density (Bmax) and affinity (Kd) (±s.e.mean) were significantly lower and higher, respectively, in normotensive than in hypertensive subjects [Bmax=327±4 vs 435±5 fmol mg−1 of protein (P<0.01) and Kd=3.76±0.05 vs 6.50±0.15 nm (P<0.01), respectively]. The 50% stimulating concentration of adrenaline on [35S]-GTPγS binding to Gi proteins was significantly (P<0.01) lower in normotensives (12±2 nm) than in hypertensives (110±10 nm). The 50% inhibiting concentration of adrenaline on forskolin-stimulated cAMP levels was significantly (P<0.01) lower in normotensive (22±2 nm) than in hypertensive subjects (200±25 nm).

Conclusions

Present analysis, including receptorial and functional data, provides evidence that marked alterations occur in platelet α2-adrenoceptors of hypertensive subjects.

Keywords: [3H]-UK 14304 binding, G proteins, cAMP, human platelets

Introduction

Several studies have implicated α2-adrenoceptors (AR) in the development and maintenance of hypertension, suggesting that alterations in the function or expression of α2-AR may contribute to this disease [1]. Human lymphocytes or platelets have frequently been used to study (patho)physiological and drug-induced alterations in the adrenergic system [2, 3]. A number of reports have compared the binding characteristics, mainly taking into account receptor density, of platelet α2-AR in essential hypertensive (EHT) and normotensive (NT) subjects. In some works, the α2-AR density was significantly higher in hypertensive subjects [4] while in others, no significant difference was observed [5]. These contrasting findings, however, might be explained by the relatively small number of subjects utilized in most of these studies. Moreover, all binding studies on α2-AR were performed using, in saturation experiments, either partial agonist or antagonist radioligands (e.g. [3H]-p-amino-clonidine, [3H]-yohimbine, [3H]-rauwolscine) which label both the high-affinity (coupled with functional responses) and the uncoupled low-affinity populations of α2-AR [6]. Finally, it has been recently suggested [7] that not all states of the α2-AR are labelled by [3H]-antagonists possibly hampering a straight interpretation of data.

In the present study we carried out a systematic analysis of platelet α2-AR in normotensive subjects and essential hypertensive patients. To determine number and affinity of platelet α2-AR, Scatchard analysis of saturation assays was performed using for the first time a full α2-AR agonist radioligand, [3H]-5-bromo-6-(2-imidazolin-2-ylamino)-quinoxaline ([3H]-UK 14304) [8], which labels only the high affinity population coupled with the functional response. Furthermore, platelet α2-AR were analyzed from a thermodynamic point of view to evaluate whether binding mechanisms are altered at the molecular level during hypertension. In addition, to correlate these data with two relevant post-receptor events, functionality of Gi proteins coupled with α2-AR was determined in all subjects examined by measuring the capability of adrenaline to stimulate [35S]-guanosine-5’-O-(3-thio)triphosphate ([35S]-GTPγS) binding to platelets. Finally as far as the effector system is concerned, forskolin-stimulated cAMP levels were measured in platelets and their inhibition by increasing concentrations of adrenaline was assessed.

Methods

Patients

The protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from each participant in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Hypertension was defined as a sitting blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg systolic or 90 mm Hg diastolic as the mean value of three sphygmomanometric determinations taken between 09.00 h and 11.00 h on at least three separate occasions in the previous 4 weeks according to information guidelines [9]. All hypertensive patients underwent routine tests ruling out secondary hypertension (plasma electrolytes and creatinine, catecholamine excretion and intravenous pyelography). Kidney function was within normal limits. History, symptoms and signs of cardiac failure, and/or treatment with digitalis were absent. There was no clinical evidence of cerebrovascular disease and all patients had stage I or II fundal changes. The subjects who took part in this study were 165 normotensive volunteers (mean systolic [±s.d.] 119±10 mmHg, mean diastolic blood pressure 83±7 mmHg; mean age 46.2±12 years) and 124 hypertensive subjects (mean systolic 163±15 mmHg, mean diastolic blood pressure 100±8 mmHg; mean age 49.4±15 years). All individuals took no medication, including aspirin, for at least 3 weeks before the study. The proportion of male/female and smoker/nonsmoker subjects in the two groups of patients, respectively normotensive and hypertensive, were closely similar. Body mass index was calculated by dividing the body weight by the square of the height and did not show any difference between the two groups. Peripheral venous blood samples (30 ml) were obtained in each participant between 09.00 and 11.00 h.

[3H]-UK 14304 binding assay in platelet membranes

The membrane preparations used in this investigation were obtained from platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and the platelets were prepared from blood previously anticoagulated and stabilized with ACD (1.4% citric acid, 2.5% sodium citrate, 2% d-glucose) according to the method of Schloos et al. [8]. PRP was centrifuged in polypropylene tubes at 17,500 g for 15 min at 25° C in a Sorvall type SS 34 rotor. The platelets were then resuspended in 2/3 of the original volume in Tris-buffer A (50 mm Tris-HCl, 20 mm EDTA, 150 mm NaCl; pH 7.4 at 25° C) and centrifuged at 17,500 g for 15 min at 25° C. Thereafter, the supernatant was discarded and the washed platelets were suspended in ice-cold hypotonic buffer B (5 mm Tris-HCl, 5 mm EDTA; pH 7.4 at 4° C) and homogenized with a Polytron for 30 s before centrifugation at 35,000 g for 15 min at 4° C. Membrane suspensions were washed three times in ice-cold Tris-buffer C (50 mm Tris HCl, 0.8 mm EDTA; pH 7.4 at 4° C) with intervening centrifugations at 35,000 g for 15 min at 4° C. The pellet was finally resuspended in the assay buffer D, containing 50 mm Tris HCl, 0.8 mm EDTA and 10 mm MgCl2 (pH 7.4 at 4° C), at a final concentration of 1 mg of protein ml−1. Saturation experiments were performed in a total volume of 250 μl, which consisted of 100 μl membrane suspension and 0.5–50 nm of [3H]-UK 14304. The non specific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μm UK 14304 or adrenaline. The incubation time was 60 min at 25° C according to the results of previous time-course experiments. The incubation was terminated by rapid filtration under vacuum over Whatman GF/C glass fiber filters, using a Brandel Cell harvester. The filters were immediately rinsed with ice-cold Tris buffer C, dried, transferred in vials containing 5 ml of liquid scintillation and counted in a Beckman LS 1800 Spectrometer (efficiency 55%). The protein concentration was determined according to a Bio-Rad method [10] with bovine albumin as reference standard. A weighted non linear least-squares curve fitting program LIGAND, [11] was used for computer analysis of saturation experiments.

Thermodynamic analysis

For the generic binding equilibrium L+R=LR (L=ligand, R=receptor) the affinity constant Ka is directly related to the standard free energy ΔG° (ΔG°=-RTlnKa) which can be separated in its enthalpic and entropic contributions according to the Gibbs equation: ΔG°=ΔH°- TΔS°. The standard free energy, ΔG° was calculated as -RTlnKa at 25° C, while the determination of the other thermodynamic parameters (ΔH° and ΔS°) was performed by Ka measurements at different temperatures (Ka=1/Kd, where Kd is the dissociation constant of the equilibrium). The standard enthalpy, ΔH°, was calculated from the van’t Hoff plot ln Kavs 1/T (whose slope is -ΔH°/R) and the standard entropy, ΔS°, as ΔS°=(ΔH°—ΔG°)[T with T=298.15 K and R=8.314 J/K/mol. Saturation experiments of [3H]-UK 14304 binding to the human platelet membranes of normotensive and hypertensive subjects were carried out on a relatively limited number of subjects (80 NT and 80 EHT, each divided into 16 pools of 5 subjects) at 0, 10, 20, 25 and 30° C using concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 50 nm.

[35S]-GTPγS binding assay in the platelet membranes

[35S]-GTPγS binding was measured with a modification of the assay used by Lorenzen et al. [12]. Membrane protein (2–4 μg) was mixed with 100 μl of reaction mixture (50 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 100 mm NaCl, 2 μm GDP, 0.3–0.5 nm [35S]-GTPγS (about 50,000 counts min−1) and 0.5% bovine serum albumin). The incubation was started by addition of reaction mixture to the membrane suspension and was carried out in at least triplicates for 2 h at 25° C. The reaction was terminated by rapid filtration through GF/C glass fiber filters under vacuum. The filters were washed four times (with 4 ml of 50 mm Tris HCl, pH 7.5, containing 5 mm MgCl2 and 100 mm NaCl), dried and treated with 5 ml Aquassure. Non specific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μm GTPγS and was less than 10% of total binding.

Measurement of cyclic AMP levels in human platelets

Washed human platelets were prepared as described by Korth et al. [13]. The final suspending medium was a Tyrode’s buffer, pH 7.4, of the following composition (mm): NaCl 137, KCl 2.68, NaHCO3 11.9, MgCl2 1.0, NaH2PO4 0.4, glucose 5.5. Platelets (6–8×104 cells) were suspended in 0.5 ml incubation mixture (Tyrode’s buffer containing bovine serum albumin (BSA) 0.25%) and preincubated for 10 min in a shaking bath at 37° C. Then adrenaline (1 nm-10 μm) plus forskolin 1 μm were added to the mixture and the incubation continued for a further 5 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of cold 6% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The TCA suspension was centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min at 4° C and the supernatant was extracted four times with water-saturated diethyl ether. The final aqueous solution was tested for cAMP levels by a competition protein binding assay carried out essentially according to Nordstedt & Fredholm [14]. The epinephrine concentration able to inhibit by 50% (IC50) forskolin 1 μm stimulated cAMP levels was obtained from concentration-response curves after log-logit transformation of dependent variables by weighted least square methods.

Drugs

Trizma base,aminophylline, cyclic AMP, GDP, forskolin, BSA (bovine serum albumin), and epinephrine were from SIGMA Chemical Company (St Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.). RO 20–1724 was a kind gift of Dr E. Kyburz, Hoffman-La Roche (Basel, Switzerland). All other reagents were of analytical grade and obtained from commercial sources. [3H]-UK 14304 (specific activity 95.1 Ci mmol−1), [35S]-GTPγS (specific activity 1224 Ci mmol−1), Aquassure and Atomlight were from NEN Research Products (Boston, Mass., U.S.A.).

Statistical analysis

The results are given as mean±s.e.mean. Comparison between groups was made with Student’s t-test. Results were considered significant at a value of P<0.05.

Results

[3H]-UK 14304 binding to platelet membranes

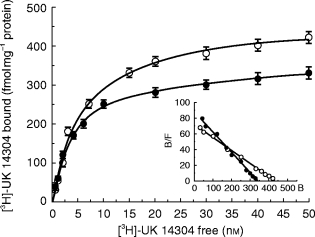

Figure 1 shows the saturation curves of [3H]-UK 14304 binding to NT and EHT subjects; the linearity of the Scatchard plots in the inset are indicative, in our experimental conditions, of the presence of a single class of binding sites. Kd values were 3.76±0.05 nm and 6.50±0.15 nm in NTs (n=165) and in EHTs (n=124), respectively; corresponding Bmax values were 327±4 and 435±5 fmol mg−1 of protein (P<0.01 vs normotensives).

Figure 1.

Saturation curves of [3H]-UK 14304 binding to platelet membranes of normotensive (•) and hypertensive (○) subjects. Experiments were performed as described in Methods. Values are the means±s.e.mean (n=165 and 124, respectively). In the inset the Scatchard plots of the same data are shown. Kd values (nm) were 3.76±0.05 and 6.50±0.15, respectively, and corresponding Bmax values (fmol mg−1 protein) were 327±4 and 435±5. Non specific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μm UK 14304 or adrenaline.

Thermodynamic binding assay

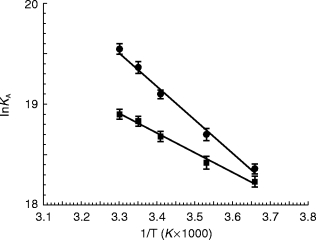

To verify whether the quantitative differences of binding parameters among the examined groups corresponded to a different molecular recognition mechanism we performed a thermodynamic analysis of binding data. Figure 2 reports van’t Hoff plots for normotensive and hypertensive subjects. The normotensive group (ΔG°=−47.88±0.07 kJ mol−1; ΔH°=27.0±2.0 kJ mol−1; ΔS°=251±8 J mol−1 K−1) differed from the hypertensive one (ΔG°=−46.55±0.05 kJ mol−1; ΔH°=16.6± 1.2 kJ mol−1; ΔS°=212±12 J mol−1 K−1, P<0.01 vs normotensives) and the binding mechanism of normotensive subjects was less enthalpic and more entropic.

Figure 2.

Van’t Hoff plots showing the effect of temperature on the equilibrium binding association constant, Ka=1/Kd, of [3H]-UK 14304 binding in platelet membranes of • normotensive and ▪ hypertensive subjects. Values are the means (±s.e.mean) of 16 separate experiments performed as described in methods. The plots are essentially linear in the temperature range investigated (0–30° C) (r≥0.97). Normotensive group (ΔG°=−47.88±0.07 kJ mol−1; ΔH°=27.0±2.0 kJ mol−1; ΔS°=251±8 J mol −1 K−1) differs from the hypertensive (ΔG°=−46.55±0.05 kJ mol−1; ΔH°=16.6±1.2 kJ mol−1; ΔS°=212±12 J mol−1 K−1, P<0.01 vs normotensives).

Adrenaline-stimulated [35S]-GTPγ S binding

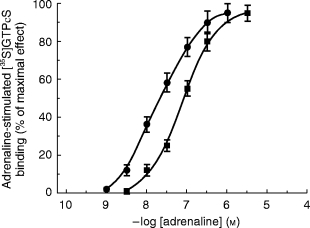

To investigate whether the differences found in binding parameters of the examined groups are followed by alterations at the level of two relevant α2-AR transduction and effector systems, we evaluated the stimulation by adrenaline of [35S]-GTPγS binding to guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G-proteins) in platelet membranes and the inhibition of forskolin 1 μm stimulated cyclic AMP levels by adrenaline in washed human platelet. Figure 3 reports typical dose-response curves of [35S]-GTPγS binding above basal levels by increasing concentrations of adrenaline (1 nm-10 μm) in NT (EC50=12±2 nm), and EHT subjects (EC50=110±10 nm, P<0.01 vs normotensives). The extent of stimulation of [35S]-GTPγS binding was dependent on the presence of high concentrations of Mg2+ (5 mm), GDP (2 μm) and NaCl (100 mm).

Figure 3.

α2-adrenergic receptor-mediated stimulation of [35S]-GTPγS binding to Gi proteins in platelet membranes of • normotensive, ▪ hypertensive subjects induced by increasing concentrations of adrenaline (1 nm-10 μm). Normotensive group (EC50=12±2 nm) differs from hypertensive subjects (EC50=110±10 nm, P<0.01 vs normotensives).

Cyclic AMP assay

Figure 4 shows typical log dose-response curves for the inhibition of forskolin stimulated cAMP levels by increasing concentrations of adrenaline (1 nm-10 μm) in NT (IC50=22±2 nm), and EHT subjects (IC50=200±25 nm, P<0.01 vs normotensives). A highly significant shift to the right in the concentration-response curve was observed in the hypertensive patients.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of forskolin (1 μM) stimulated cAMP levels by increasing concentrations of adrenaline (1 nm-10 μm) in platelets of • normotensive, ▪ hypertensive subjects. Normotensive group (IC50=22±2 nm) differs from hypertensive subjects (IC50=200±25 nm, P<0.01 vs normotensives).

Discussion

The present study focuses on alterations of the targets of cathecolamines, the adrenergic receptors, in human platelets. Although numerous studies exist on α2-AR in essential hypertension, controversial results are reported about changes in the properties of these receptors. With radioligand binding studies it is possible to measure directly changes in receptor density and affinity. In previous works on receptor binding, α2-AR have been identified with various radioligands (antagonists or partial agonists), and the existence of multiple conformational states for this receptor has been demonstrated [15]. Recent theories postulate that G-protein coupled receptors are in a state of equilibrium between the inactive conformation (R), and a spontaneously active conformation (R*) that can be coupled to G-protein in the absence of ligand [16]. Recently,MacKinnon et al. [7] suggested that α2-AR [3H]-antagonists could not label these receptors (R*) if it is assumed that antagonists, having no efficacy, cannot induce the conformational change required for diffusional-dependent G protein coupling. In human platelets, only the high-affinity population (R*) of the α2-AR is coupled with functional responses; therefore the binding of [3H]-labelled agonists could be relevant in the study of pathological processes in which alterations of the α2-adrenoceptor function are postulated [17]. Consequently, to label α2-AR ofhuman platelet membranes we employed for the first time the selective full agonist [3H]-UK 14304 [8].

Our results indicate that α2-AR Kd and Bmax values are significantly higher in the hypertensive than in the normotensive subjects. Increased sympathetic nervous activity appears to trigger cellular mechanisms that increase receptor density, while, normally, excess of stimulation produces receptor uncoupling and internalization, leading to a decrease in receptor density [18]. This increase in Bmax appears to be ‘compensated’ by an increase in Kd value. Moreover, thermodynamic analysis of binding data indicate that [3H]-UK 14304 binding in NTs is less enthalpic and more entropic than that in EHTs showing that binding mechanisms are altered during hypertension. To evaluate whether the differences between normotensive and hypertensive binding parameters were linked also to altered signal transduction pathways we investigated the G-protein functionality as well as the hormonal regulation of adenylyl cyclase activity. We have found the stimulation of [35S]-GTPγS binding to Gi-proteins by adrenaline to be lower in EHTs than in NTs. Moreover, the results of the cyclic AMP assay suggest that adrenaline is more efficient in inhibiting forskolin-stimulated cAMP levels in platelets from normotensive patients. These functional results are in agreement with recent observations [19] showing that Gi protein levels(Giα2, Giα3)are decreased in platelets from hypertensive patients which could, at least in part, explain the attenuated responsiveness of adenylyl cyclase of this group. We cannot exclude that at least part of the changes we found in α2-AR structure and function may be due to higher plasma catecholamine levels in hypertensive subjects. However, overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system with higher circulating noradrenaline levels is present only in a proportion of essential hypertensive patients, principally younger patients with hypertension in its earlier, developmental phase [20–24]. Our hypertensive group included subjects with a wide age range. The plasma adrenaline concentrations are less commonly elevated in essential hypertension than are the plasma levels of noradrenaline [25]. The change we found in α2-AR structure and function of essential hypertensive subjects are comparable with studies with central sympatholytic antihypertensive agents [26] and suggest that, as with other tissues, platelet α2-AR density may be primarily regulated by sympathetic nerve activity rather than circulating catecholamines.

It is generally accepted that the quantitative influence of various factors on a specific AR type studied in accessible tissues (including platelets) can be reasonably extrapolated and applied to the same receptor type elsewhere, e.g. the central nervous system [1]. However, recent studies in animals seem to contradict this assumption, by showing that α2c-AR subtypes predominate in a number of areas in the central nervous system of the rat [27], whereas platelet AR are of the α2A subtype. In addition, studies in knockout mice suggest that stimulating α2A-AR mediates hypotension, whereas stimulation of α2B-AR causes hypertension [28, 29]. Hence, the structural and functional changes in platelet α2-AR and coupled Gi proteins which we found to be present in essential hypertensive subjects remain unexplained in its pathophysiological significance. Better characterization of the normal structure and function of α2-AR subtypes in humans is still needed before the significance of their changes in hypertension can be appreciated.

Acknowledgments

This study was jointly supported by a grant from Azienda Ospedaliera S. Anna and University of Ferrara.

References

- 1.Gavras H, Handy D, Gavras I. Alpha-adrenergic receptors in hypertension. In: Laragh JH, Brenner BM, editors. Hypertension: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. New York: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 853–861. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brodde OE, Daul AE, O’Hara N, Khalifa AM. Properties of α- and β-adrenoceptors in circulating blood cells of patients with essential hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1985;7(Suppl 6):S162–S167. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198500076-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodde OE, Beckering JJ, Michel MC. Human heart β-adrenoceptors: a fair comparison with lymphocyte β-adrenoceptors? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1987;8:403–407. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michel MC, Brodde OE, Insel PA. Peripheral adrenergic receptors in hypertension. Hypertension. 1990;16:107–120. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.16.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blankesteijn WM, Graafsma SJ, van Tits LJH, Hectors MPC, Thien T. Adrenoceptors on blood cells in patients with primary hypertension: correlation with blood pressure and related variables. J Hypertens. 1993;11:995–1002. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199309000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor P, Insel PA. Molecular basis of pharmacologic selectivity. In: Pratt WB, Taylor P, editors. Principles of Drug Action-The Basis of Pharmacology. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1990. pp. 1–102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacKinnon AC, Spedding M, Brown CM. Sodium modulation of [3H]-agonist and [3H]-antagonist binding to α2-adrenoceptor subtypes. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;109:371–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schloos J, Wellstein A, Palm D. Agonist binding at alpha2-adrenoceptors of human platelets using [3H]-UK-14304: regulation by Gpp(NH)p and cations. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1987;336:48–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00177750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The fifth report of the Joint National Committee on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure (JNCV) Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:154–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye-binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72 doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munson PJ, Rodbard D. Ligand: a versatile computerized approach for the characterization of ligand binding systems. Anal Biochem. 1980;107:220–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorenzen A, Fuss M, Vogt H, Schwabe U. Measurement of guanine nucleotide-binding protein activation by A1 adenosine receptor agonists in bovine brain membranes: stimulation of guanosine-5’-O-(3-[35S]thio) triphosphate binding. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korth R, Nunez D, Bidault J, Benveniste J. Comparison of three paf-acether receptor antagonist ginkgolides. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;152:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90840-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nordstedt C, Fredholm MM. A modification of a protein-binding method for rapid quantification of cAMP in cell culture supernatants and body fluids. Anal Biochem. 1990;189:231–234. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90113-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meana JJ, Barturen F, Garcia-Sevilla JA. Characterization and regional distribution of α2-adrenoceptors in post mortem human brain using the full agonist [3H]-UK 14304. J Neurochem. 1989;52:1210–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bond RA, Leff P, Johnson TD, et al. Physiological effects of inverse agonists in transgenic mice with myocardial overexpression of the β2-adrenoceptor. Nature. 1995;374:272–276. doi: 10.1038/374272a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Sevilla JA, Guimon J, Garcia-Vallejo P, Fuster MJ. Biochemical and functional evidence of supersensitive platelet α2-adrenoceptors in major affective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:51–57. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800010053007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenakin T. Stimulus-response mechanisms: Pharmacologic Analysis of Drug-Receptor Interaction. New York: Raven Press; 1993. pp. 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marcil J, Schiffrin EL, Anand-Srivastava MB. Aberrant adenylyl cyclase/cAMP signal transduction and G protein levels in platelets from hypertensive patients improve with antihypertensive drug therapy. Hypertension. 1996;28:83–90. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esler M, Jennings G, Biviano B, Lambert G, Hasking G. Mechanism of elevated plasma noradrenaline in the course of essential hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1986;8(suppl 5):S39–S43. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198608005-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Esler M, Jenings G, Korner P, et al. Assessment of human sympathetic nervous system activity from measurements of norepinephrine turnover, Hypertension. 1988;11:3–20. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guzzetti S, Piccaluga E, Csati R, et al. Sympathetic predominance in essential hypertension: a study employing spectral analysis of heart rate variability. J Hypertens. 1988;6:711–717. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada Y, Miyajima E, Tochikubo O, Ishii M. Age-related changes in muscle sympathetic nerve activity in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1989;13:870–877. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson EA, Sinkey CA, Lawton WJ, Mark AL. Elevated sympathetic nerve activity in borderline hypertensive humans. Evidence from direct intraneural recordings. Hypertension. 1989;14:177–183. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.14.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldstein DS. Plasma catecholamines and essential hypertension. An analytical review. Hypertension. 1983;5:86–99. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.5.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshiro T, Miura Y, Kimura S, et al. Functional relationships between platelet alpha2-adrenoceptors and sympathetic nerve activity in clinical hypertensive states. J Hypertens. 1990;8:1097–1104. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholas AP, Pieribone V, Hokfelt T. Distributions of mRNAs for alpha-2 adrenergic receptor subtypes in rat brain: an in situ hybridization study. J Comp Neurol. 1993;328:575–594. doi: 10.1002/cne.903280409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Link RE, Desai K, Hein L, et al. Cardiovascular regulation in mice lacking alpha2-adrenergic receptor subtypes b and c. Sciences. 1996;273:803–805. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacMillan LB, Hein L, Smith MS, Piascik MT, Limbird LE. Central hypotensive effects of the alpha2a-adrenergic receptor subtype. Science. 1996;273:801–803. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5276.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]