Abstract

Aims

The purpose of the present study was to assess the pharmacokinetics of the novel selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist SDZ HTF 919 (HTF) including food effect, absolute bioavailability, interoccasion and intersubject variabilities.

Methods

In the randomized, open-label, three treatment, four period crossover study, HTF was administered to 12 young healthy male subjects as a 12 mg tablet (twice under fasted and once under fed conditions) and a 3 mg intravenous (i.v.) infusion over 40 min (fasted). Pharmacokinetic parameters were obtained by noncompartmental methods. A more comprehensive pharmacokinetic characterization was achieved by integrated modelling of oral (p.o.) and i.v. data. To describe the absorption phase a Weibull function and a classical first order input function were compared.

Results

Noncompartmental pharmacokinetic analysis revealed a rapid absorption (tmax 1.3 h, fasted), an absolute bioavailability of 11±3%, a biphasic disposition phase with a terminal half-life of 11±5 h, a clearance of 77±15 l h−1, and a volume of distribution at steady state of 368±223 l. The coefficients of interoccasion and interindividual variability in Cmaxand AUC ranged between 17 and 28%. Food intake caused a delay (tmax 2.0 h) and decrease in absorption with consequently lower systemic exposure (≈5% absolute bioavailability). Integrated p.o./i.v. pharmacokinetic modelling with a Weibull input function allowed accurate description of individual profiles. Modelling of the data from the p.o. dosing improved the description of the terminal phase by inclusion of the i.v. data and additionally provided quantitative characterization of the absorption phase.

Conclusions

The pharmacokinetics of HTF could be well described by an integrated modelling approach for both p.o. and i.v. data. The derived model will provide guidance in the design of future studies.

Keywords: 5-HT4 receptor agonist, modelling, pharmacokinetics, SDZ HTF 919, Weibull function

Introduction

Recently selective 5-HT4(5-hydroxytryptamine=serotonin) receptor agonists have been suggested to be of potential therapeutic use in the treatment of gastrointestinal motility disorders such as irritable bowel disease (IBS) [1, 2]. Because of their modulation of neurotransmitter release within the enteric nervous system [3, 4], 5-HT4 receptor agonists are currently under clinical investigation for their potential to elicit promotile activity in man [5].

SDZ HTF 919 [HTF, 5-methoxy-indole-3 carboxaldehydeamino(pentylamino)methylene-hydrazone] is a selective partial agonist at the 5-HT4 receptor [6, 7]. In vitroand in vivo investigations in animals on HTF’s promotile properties have been reported earlier [8]. A triggering of the peristaltic reflex has also been demonstrated in preliminary studies in human intestine [9]. The first studies with HTF in healthy male subjects [10, 11] indicated changes in stool characteristics such as more frequent defecations and looser stools with increased dose. Further, shortening of total colonic transit time was observed as assessed by the radiopaque marker technique [12, 13]. The multiple-dose safety and tolerability study [10] also provided preliminary information on the pharmacokinetics of HTF. Single (SD) and subsequently twice-daily multiple (MD) doses of 25, 50, and 100 mg HTF for 14 days indicated no deviation from dose proportional pharmacokinetics. Steady-state concentrations of HTF were reached after 8 days of chronic dosing and exhibited moderate accumulation. The safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic results in this first study with HTF in man warranted further clinical pharmacological characterization of HTF. Reproducible and predictable pharmacokinetics are desirable in gastrointestinal motility disorders with variable disease course such as IBS.

The present paper reports on the integrated pharmacokinetic characterization of HTF following SD p.o. (tablet) and i.v. administrations to healthy male subjects. Absolute bioavailability, interoccasion and interindividual variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters, and the effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of HTF are presented. In addition, a simultaneous p.o./i.v. pharmacokinetic modelling approach was explored.

Methods

Subjects

Twelve healthy male subjects aged 19–31 years, and within ±20% of their ideal body weight entered and completed this study. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to enrolment in the study which was conducted at Hôpital Stell, Paris, France after review by a local Institutional Review Board. The subjects’ health was assessed by medical history, physical examination, clinical laboratory testing (serology, haematology, blood chemistry, urinalysis), 12-lead ECG recordings, and vital signs determinations. All subjects were free from concomitant medications for at least 1 week prior to commencement and during the study. Subjects participating in the study did not smoke more than 10 cigarettes per day and did not consume more than 3 cups of coffee daily. Tests for drugs of abuse in urine and an alcohol breath analysis were performed at screening and 1 day prior to each drug administration. Alcohol was not allowed from 2 days prior to the study until its completion.

Design

Single oral doses of 12 mg under fasted (two times) and fed conditions (once) and an infusion of 3 mg HTF over 40 min were investigated to assess absolute bioavailability, interoccasion and interindividual variability in the major pharmacokinetic characteristics, and the effect of food on the pharmacokinetic profile. The 3 mg i.v. dose was chosen for reasons of assay sensitivity. Previous unpublished studies had shown good tolerability of HTF for single i.v. doses up to 80 mg. A randomized, open-label, three treatment, four period crossover design was applied. Two single oral doses of HTF under fasting conditions were administered to assess the interoccasion and intersubject variability in the pharmacokinetic parameters. The washout period between subsequent administrations was at least 1 week. HTF tablets (12 mg) were administered with 150 ml noncarbonated water. Subjects fasted from 12 h before dosing until 4 h after drug administration in the morning. Smoking was not allowed on the days of drug administration until after lunch. Xanthine-containing beverages and food were not allowed from 12 h before drug administration until the last blood sampling. The composition of meals was standardized and identical for all subjects on the days of pharmacokinetic profiling. For assessment of the food effect, a fat-rich breakfast was consumed 0.5 h before drug intake. It contained 150 ml orange juice, two rolls, 20 g butter, 25 g marmalade, two fried eggs, two slices of bacon and 200 ml of whole milk.

Assessments

Safety and tolerability

Adverse event reporting included onset, duration, intensity, and potential causal relationship. The adverse events (on days of pharmacokinetic profiling and during wash-out periods), vital signs (at screening, on days of pharmacokinetic profiling, and at study completion), clinical laboratory data (at screening, immediately before each drug administration, and at study completion), and ECG recordings (at screening and study completion) were evaluated descriptively. Individual vital signs data were screened for values outside the predetermined normal ranges, i.e. 100–140 mmHg for systolic blood pressure, 50–90 mmHg for diastolic blood pressure, and 50–100 beats min−1 for pulse rate. A change in systolic blood pressure value of >20 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >10 mmHg upon standing was defined as orthostatic hypotension. Clinical laboratory values were compared with the normal ranges supplied by the analysing laboratory. ECGs were evaluated for clinically relevant abnormalities.

HTF analysis

For the determination of HTF concentrations in plasma, serial blood samples (4.5 ml) were drawn from an antecubital vein just before and 0.33, 0.67, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 18, 24, 32, and 48 h post-dose following p.o. intake. The blood sampling schedule for the infusion differed in the initial part with collections just before and 0.25, 0.5, 0.67, 0.75, 0.83, 1, 1.33, 1.66, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 h post-dose. From the 8 h time point onwards blood samples were taken as for the p.o. administrations. Plasma samples were stored at −18° C pending analysis.

Plasma concentrations of HTF were determined using a specific GC-MS method with heptafluorobutyric acid anhydride derivatization and negative chemical ionization [14]. In brief, buffered plasma (1 ml, pH 10) including an internal standard was extracted with methyltertiarybutylether. After centrifugation the organic layer was evaporated and the residue dissolved in ethylacetate and heptafluorobutyric acid anhydride. Derivatization was performed at 50° C for 1 h. The residue was taken up in toluene and 3 μl were injected onto the analytical column (fused silica capillary CP SIL8 CB, 25×0.25 mm, helium as carrier gas). HTF was detected by negative chemical ionization with fragment m/z=351 for HTF and fragment m/z=379 for the internal standard. Calibration curves consisted of nine standard concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 80 ng ml−1. The limit of quantification was 0.1 ng ml−1. Batch-to-batch accuracy varied from +2.3 to +10.3% (n=84). Precision among batches ranged from 7.3 to 11.9% (n=84).

Pharmacokinetics

Plasma concentration vs time profiles of HTF for the four treatments were evaluated by standard noncompartmental methods. In addition, integrated p.o. (2x)/i.v. pharmacokinetic modelling was performed on the two single oral dose and one infusion data sets obtained under fasted conditions. Results are provided for the i.v. and p.o. administrations (both separately for the two identical oral treatments of HTF and after averaging individual data).

Noncompartmental pharmacokinetic evaluation

For the noncompartmental pharmacokinetic analysis [15], maximum plasma concentration (Cmax), time to reach Cmax (tmax), and the time to first measurable concentration (tlag) were read from the measured values. The rate constant associated with the terminal phase (λz) and its corresponding half-life (ln(2)/λz) were calculated from the log-linear terminal slope of the plasma concentration-time profile by least squares linear regression analysis. The area under the plasma concentration vs time profile (AUC) was assessed in the ascending phase by the linear trapezoidal rule and in the descending phase by the log-linear trapezoidal rule with extrapolation to infinity. The apparent oral clearance (CL/F), with F denoting the fraction of dose being bioavailable, was obtained by division of dose by AUC. The apparent volume of distribution associated with the terminal phase (Vz/F) was estimated by division of CL/F by λz. The volume of distribution at steady state determined from the infusion data was assessed by Vss=CL(MRT−(T/2)), with MRT being the mean residence time (AUMC/AUC with AUMC denoting the area under the first moment-time curve) and T denoting the infusion duration. The absolute bioavailability was calculated as F=(AUCp.o./AUCi.v.)(Dosei.v./Dosep.o.).

Compartmental pharmacokinetic evaluation

A sound characterization of the terminal phase of the concentration vs time profile of HTF following p.o. dosing was hampered by the limited assay sensitivity. The i.v. administration of 3 mg HTF as an infusion over 40 min yielded a markedly higher systemic exposure than that following intake of a 12 mg tablet. Plasma concentrations therefore were detectable for a longer time postdose.

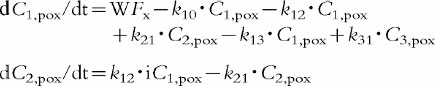

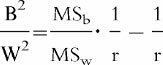

An integrated p.o. (2x)/i.v. modelling approach was applied to characterize the pharmacokinetics after p.o. dosing with support of the more informative i.v. data. Model building included four steps. First, a mammillary open three-compartment model was compared with one including only two compartments. Secondly, model discrimination was applied comparing a first order and a Weibull input function WF [16]. This input function is considered an appropriate approximation of the absorption time distribution [17]. Thirdly, the inclusion of a lag-time vs no lag-time was investigated. Fourthly, the performance of the integrated p.o. (2x)/i.v. model was explored using an average and two separate p.o. pharmacokinetic profiles. As measures of goodness of fit for model selection Weighted least squares, Akaike, and Schwarz criteria were calculated [18, 19]. Based on this statistical evaluation a mammillary open three-compartment model with elimination from the central compartment was chosen with a separate Weibull function for the absorption phase of each oral data set including a lag-time. The same disposition model was used for both the p.o. and i.v. routes of administration. The three sets of differential equations are provided below.

Intravenous infusion [15]

Two oral administrations (x=1 or 2)

|

|

Primary parameters

tdx time lag, 1st parameter of Weibull function

(x=1 or 2)

τ−1 2nd parameter of Weibull function

sx shape factor, 3rd parameter of Weibull function

(x=1 or 2)

k10, k12, k21, k13, k31, Vc, F [15]

Secondary parameters

AUC, CL/F, λz, Vz/F, Vss [15]

Nonlinear regression analysis was performed using the SIMUSOLV software [20]. Three sets of equations, describing two oral and one infusion pharmacokinetic profile for each subject, were fitted simultaneously. Numerical integration [Gear’s backward difference formulas algorithm, 20] was conducted by maximizing the extended least-square criterion. The convergence criterion was set at 1.E-5. A proportional error model was used reflected in the variance model v=a2Ŷ2 with v denoting the variance, ‘a’ being a proportionality factor and Ŷ indicating the predicted value of the dependent variable.

Statistical evaluation

Results are expressed as mean±standard deviation (s.d.). An analysis of variance (anova) was applied with treatment, period, sequence, and subject(sequence) as sources of variation [21]. Pairwise comparisons of the pharmacokinetic parameters between the two p.o. administrations under fasted conditions did not yield significant differences as assessed by least squares differences. Consequently, the respective pharmacokinetic characteristics of the two p.o. fasted treatments were pooled and the anova outlined above was repeated. Estimate statements were formulated to statistically compare (1) the pharmacokinetics of HTF after p.o. administration under fasted and fed conditions and (2) the dose-normalized pharmacokinetic parameters after p.o. and i.v. dosing. As nonparametric statistical approach an anova over ranks (Friedman’s test) was performed [21].

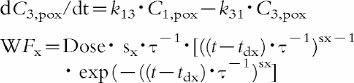

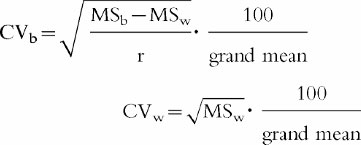

The coefficients of interoccasion (CVw) and intersubject variability (CVb) for Cmax and AUC (noncompartmental evaluation) obtained from the two p.o. administrations of HTF under fasted conditions were derived according to Albert and Smith [22].

|

with MSw denoting within-subject mean square, MSb between-subjects mean square, and r replicates (duplicates). Between-subject (B2) and within-subject (W2) variance were compared by calculating the ratio

|

Between-subject variance was considered greater than within-subject variance if the lower limit of the 95% confidence interval exceeded unity.

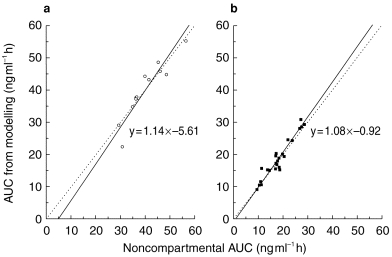

In order to judge the predictability of the integrated pharmacokinetic modelling approach an orthogonal regression analysis [23] was performed on the relationship between the parameter AUC obtained from simultaneous p.o./i.v. modelling and that of the noncompartmental evaluation.

Results

Safety and tolerability

No clinically relevant changes were observed in physical examination, clinical laboratory measurements, and ECG during the study. Adverse events were transient, of mild to moderate intensity, and resolved without therapeutic intervention. These included mainly watery/loose stool which is related to the promotile activity of HTF. Flatulence and headache were the second and third most frequently experienced adverse events. Headache has been reported to exhibit a dose-dependent occurrence in earlier studies [10]. Two subjects showed symptomatic orthostatic hypotension after oral drug administration once under fasted and once under fed conditions; its relationship to drug administration is uncertain, since no placebo control was investigated.

Pharmacokinetics

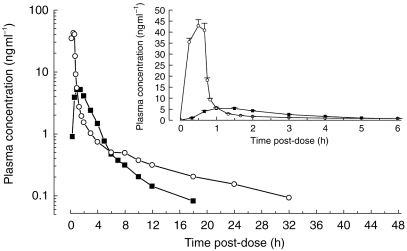

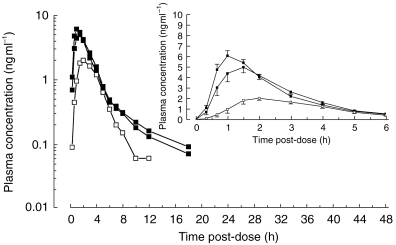

The mean plasma concentration–time profiles of single i.v. and p.o. administrations of HTF under fasted conditions are shown in Figure 1. Figure 2 graphically illustrates the reproducibility of the single dose pharmacokinetics of HTF after the two p.o. administrations under fasting conditions and additionally depicts the effect of concomitant food intake on the pharmacokinetics of HTF. The noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters are provided in Table 1. The absolute bioavailability was found to be ≈10%. Oral administration of HTF together with food caused mean Cmax and AUC to decrease by about 55%, compared with the fasted drug intake (P<0.05). The results from the nonparametric evaluation confirmed those using the parametric approach. tmax was prolonged from 1.1/1.5 h to on average 2.1 h after HTF intake together with breakfast. For those subjects in whom determination of the terminal half-life was possible following concomitant food and drug intake, this parameter was comparable with the fasted situation. Due to the fact that only 4 of 12 subjects displayed a second disposition phase in the concentration-time profile under the fed condition, the respective AUC values are likely to be underestimated and consequently CL/F and Vz/F may be overestimated.

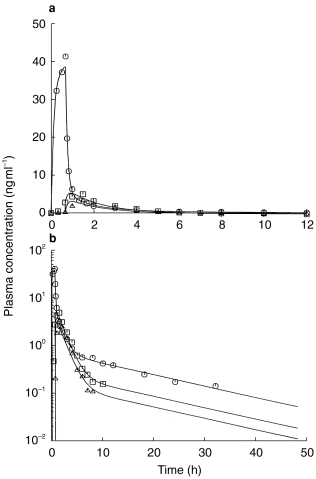

Figure 1.

Semilogarithmic and linear (insert) plasma concentration-time profiles of single p.o. (mean of two administrations of 12 mg tablet, ▪) and i.v. (3 mg as an infusion over 40 min, ○) administrations of HTF under fasted conditions (mean+s.e.mean, n=12).

Figure 2.

Semilogarithmic and linear (insert) plasma concentration-time profiles of the two fasted single p.o. (▪) and the fed (□) administrations of 12 mg HTF (mean + or − s.e. mean, n=12).

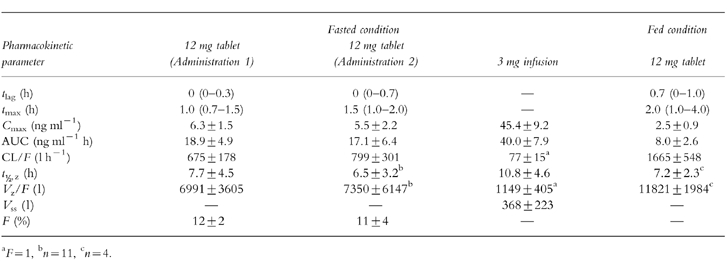

Table 1.

Noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters (mean±s.d. or median with range) of HTF after single p.o. (12 mg) and i.v. (3 mg as an infusion over 40 min) administrations under fasted (p.o., i.v.) and fed (p.o.) conditions (n=12).

The coefficients of interoccasion and intersubject variability for the two fasted p.o. administrations were 28 and 17% for Cmax and 21 and 23% for AUC. Pvalues from anova on logarithmically transformed data were 0.12 and 0.15, respectively.

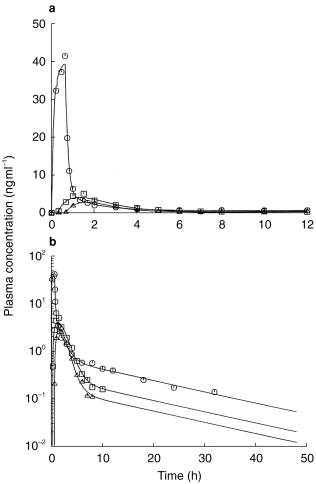

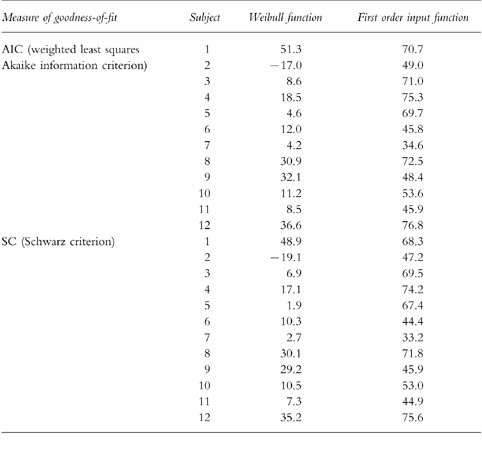

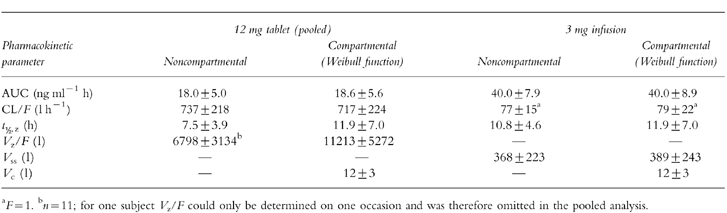

The pharmacokinetic profiles obtained from the integrated p.o. (2x)/i.v. modelling are provided for a typical subject in Figure 3 using a Weibull input function and in Figure 4 with a classical first order input function. The respective estimated pharmacokinetic parameters are shown in Table 2. The graphs indicate that the experimental concentration–time data following p.o. administration were better described by the Weibull function as compared with the first order input function. This finding was supported by individual statistics with lower values of the two goodness-of-fit parameters, the Akaike information criterion and the Schwarz criterion, for the model with the Weibull input funtion (Table 3). The experimental data were well described by the common disposition parameters for both the i.v. and p.o. administration (logarithmic presentations of Figures 3 and 4). However, the specific shape of the ascending phase was estimated separately for the two p.o. pharmacokinetic profiles as indicated by the goodness-of-fit criteria (linear presentations of Figures 3 and 4. The pharmacokinetic parameters obtained from the modelling using a Weibull function are in good agreement with the results from the noncompartmental evaluation (Table 4). The good predictability of the integrated modelling approach is additionally supported by the strong relationship between the AUC values from modelling and those from the noncompartmental evaluation Figure 5.

Figure 3.

Linear (a) and semilogarithmic (b) plasma concentration-time profiles from the integrated p.o. (2x, □, Δ)/i.v. (○) pharmacokinetic modelling using a Weibull function as input function.

Figure 4.

Linear (a) and semilogarithmic (b) plasma concentration-time profiles from the integrated p.o. (2x, □, Δ)/i.v. (○) pharmacokinetic modelling using a classical first order input function.

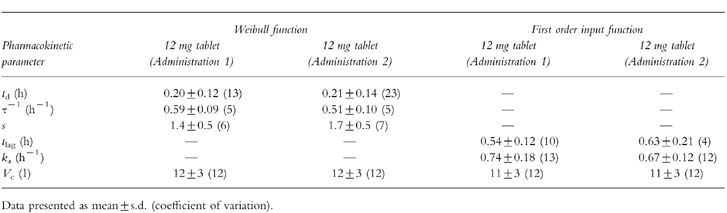

Table 2.

Parameters of Weibull input function and of a classical first order input function of the two oral concentration-time profiles following integrated p.o. (2×)/i.v. pharmacokinetic modelling (n=12).

Table 3.

Measures of goodness-of-fit from the integrated p.o. (2×)/i.v. pharmacokinetic modelling with a Weibull input function and a classical first order input function (n=12).

Table 4.

Comparison of noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters of HTF with those obtained from the integrated p.o. (2×)/i.v. pharmacokinetic modelling (mean±s.d., n=12).

Figure 5.

Orthogonal regression (solid line; line of identity dotted line) between AUC values obtained from the integrated p.o. (2x)/i.v. pharmacokinetic modelling and those from the noncompartmental analysis following i.v. (3 mg as an infusion over 40 min, a, ○, n=12) and single p.o. (12 mg, b, ▪, n=2×12) administrations of HTF.

Discussion

The present study was performed to characterize the pharmacokinetics of HTF following i.v. and p.o. (tablet, fasted and fed) administrations to 12 healthy male subjects. The two p.o. administrations of HTF (fasted) allowed estimation of the interoccasion and intersubject variability in the major pharmacokinetic parameters.

Single doses of 3 mg HTF given as infusion and 12 mg as a tablet were generally well tolerated in all subjects. Healthy male subjects were chosen for this study to avoid variability of gastrointestinal transit due to gender [13, 24].

The single oral dose pharmacokinetic results of this study using a tablet formulation refine the previously reported characteristics obtained with a capsule formulation [10]. After rapid absorption the drug displays a multiple-phase, postabsorptive pharmacokinetic profile. The initial rapid distribution phase was detectable only following i.v. administration. The more informative i.v. data additionally provided estimates of clearance, volume of distribution at steady state, and absolute bioavailability. In this light, the terminal half-life obtained from the noncompartmental p.o. evaluation is to be interpreted with caution, since the p.o. pharmacokinetic profile revealed mixed distribution and elimination phases compared to the i.v. concentration-time curve with three postabsorptive phases. Based on the present study and a recently performed human absorption-distribution-metabolism-elimination study using radiolabeled drug (data not shown), HTF belongs to the high clearance drugs. The moderate oral bioavailability of ≈10% corresponds with the i.v. clearance and apparent oral clearance data.

Drug administration after a fat-rich breakfast reduced the availability of HTF by ≈55% and prolonged the time to maximum concentration, a typical characteristic of a food effect. HTF therefore exhibits a food interaction of the decreased drug absorption type. The real food effect may be less pronounced for HTF due to an underestimation of the AUC under fed conditions as a consequence of the inability to estimate the terminal half-life required to extrapolate the AUC to infinity. A decrease in AUC can be explained by a higher apparent oral clearance after food intake compared to the fasted administration. It has been suggested that high clearance drugs be not given together with meals but in a fixed time-interval before or after meals [25].

Characterization of the interoccasion and interindividual variabilities in the pharmacokinetic characteristics of HTF support sample size determination for future pharmacokinetic studies. The variability in the pharmacokinetics of HTF assessed in the present study in fasting healthy male subjects is thought to be representative for the clinical situation, because 1) HTF is recommended to be given prior to meals and 2) there was no effect of gender on the pharmacokinetics of HTF (Novartis Pharma AG, data on file). Statistical analysis indicated that coefficients of interoccasion and intersubject variability did not differ for the main pharmacokinetic characteristics investigated.

Integrated modelling was performed to characterize the pharmacokinetics of HTF following the oral route of administration by using supportive data from i.v. dosing. A mammillary three compartment model with a Weibull function for the absorption phase using two separate p.o. data sets was derived. Based on statistical grounds, a three compartment model also for the p.o. administration was clearly to be preferred over a two compartment model, although the initial postabsorptive distribution phase was not evident from the raw plasma concentration-time data. This is in agreement with reports on the appearance of an additional initial distribution phase often only after i.v. dosing [26]. A standard first-order process did not adequately describe the apparently complex drug absorption of HTF after oral administration. The Weibull input function was preferred over a first order input function based on lower Akaike and Schwarz information criteria. This relatively complex drug input profile may reflect rate limiting release from the solid dosage form and/or variable drug absorption rates along the gastrointestinal tract. Although the more flexible Weibull function satisfactorily described the absorption characteristics of orally administered HTF in this study it is an empirical method and the constants used have no physiological meaning.

This study characterized the oral and intravenous pharmacokinetics of HTF in healthy male subjects. It is the first explorative study which investigated the effect of food, absolute bioavailability, interoccasion and interindividual variability in the pharmacokinetics of HTF. The selected integrated pharmacokinetic model is expected to be supportive in dose selection during planning of subsequent trials. Further investigations should prove its applicability in the patient population. In conclusion, pharmacokinetic characterization in this study of the tablet formulation warrants further clinical development of HTF.

References

- 1.Talley NJ. Review: 5-hydroxytryptamine agonists and antagonists in the modulation of gastrointestinal motility and sensation: clinical implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1992;6:273–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1992.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saxena PR. Serotonin receptors: Subtypes, functional responses and therapeutic relevance. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;66:339–368. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(94)00005-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonini M, Rizzi CA, Manzo L, Onori L. Novel enteric 5-HT4 receptors and gastrointestinal prokinetic action. Pharm Res. 1991;24:5–14. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(91)90059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kilbinger H, Wolf D. Effects of 5-HT4 receptor stimulation on basal and electrically evoked release of acetylcholine from guinea-pig myenteric plexus. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1992;345:270–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00168686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eglen RM, Hegde SS. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) 4receptors: Physiology, pharmacology and therapeutic potential. Exp Opin Invest Drugs. 1996;5:373–388. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchheit K-H, Gamse R, Giger R, et al. The serotonin 5-HT4 receptor. 1. Design of a new class of agonists and receptor map of the agonist recognition site. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2326–2330. doi: 10.1021/jm00013a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchheit K-H, Gamse R, Giger R, et al. The serotonin 5-HT4 receptor. 2. Structure-activity studies of the indole carbazimidamide class of agonists. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2331–2338. doi: 10.1021/jm00013a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfannkuche H-J, Buhl T, Gamse R, Hoyer D, Mattes H, Buchheit K-H. The properties of a new prokinetically active drug. SDZ HTF 919. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1995;7:280. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grider JR, Foxx-Orenstein F. A selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist stimulates transmitter release and activates the intestinal peristaltic reflex. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1075. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appel S, Kumle A, Hubert M, Duvauchelle T. First pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic study in humans with a selective 5-HT4 receptor agonist. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37:229–237. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04785.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appel S, Kumle A, Meier R. Clinical pharmacodynamics of SDZ HTF 919, a new 5-HT4 receptor agonist, in a model of slow colonic transit. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;62:546–555. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaussade S, Roche H, Khyari A, Couturier D, Guerre J. Mesure du temps de transit colique (TTC): description et validation d’une nouvelle technique. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1986;10:385–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metcalf AM, Phillips SF, Zinsmeister AR, MacCarty RL, Beart RW, Wolff BG. Simplified assessment of segmental colonic transit. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:40–47. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hubert M. 1996. Data on file, Novartis Pharma AG, Switzerland.

- 15.Gibaldi M, Perrier F. Pharmacokinetics. New York and Basel: Marcel Dekker Inc; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piotrovskii VK. Pharmacokinetic stochastic model with Weibull-distributed residence times of drug molecules in the body. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;32:515–523. doi: 10.1007/BF00637680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piotrovskii VK. The use of Weibull distribution to describe the in vivo absorption kinetics. J Pharm Biopharm. 1987;15:681–686. doi: 10.1007/BF01068420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaoka K, Nakagawa T, Uno T. Application of Akaike′ s information criterion (AIC) in the evaluation of linear pharmacokinetic equations. J Pharmacokin Biopharm. 1978;6:165–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01117450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludden TM, Beal SL, Sheiner LB. Comparison of the Akaike’s information criterion, the Schwarz criterion and the F-test as guides to model selection. J Pharmacokin Biopharm. 1994;22:431–445. doi: 10.1007/BF02353864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steiner EC, Rey TD, McCroskey PS. Midland US: Dow Chemical Company; 1993. SIMUSOLV, Version 3.0: Modelling and simulation software. [Google Scholar]

- 21.SAS Proprietary Software. Cary NC, US: SAS Institute Inc.; User’s Guide, Release 6.08. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albert KS, Smith RB. Bioavailability assessment as influenced by variation in drug absorption. In: Albert KS, editor. Drug absorption and disposition: Statistical considerations. Washington DC: American Pharmaceutical Association; 1980. pp. 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Velde EA. Orthogonal regression equation. In: Van den Besselaars T, Gralnick AMHP, Lewis SM, editors. Thromboplastin calibration and oral anticoagulant control. Boston, US: Martinus Nijhoff Publications; 1984. pp. 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier R, Beglinger C, Dederding JP, et al. Alters-und geschlechtsspezifische Normwerte der Dickdarmtransitzeit bei Gesunden. Schweiz Med Wschr. 1992;122:940–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welling PG. Effect of food on drug absorption. Pharmac Ther. 1989;4:425–441. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(89)90019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner J-G. Linear pharmacokinetic models and vanishing exponential terms: implications in pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1976;4:395–425. doi: 10.1007/BF01062829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]