Abstract

Aims

Because of the importance of treating dyslipidaemia in the prevention of ischaemic heart disease and because patient selection criteria and outcomes in clinical trials do not necessarily reflect what happens in normal clinical practice, we compared outcomes from bezafibrate, gemfibrozil and simvastatin therapy under conditions of normal use.

Methods

A random sample of 200 patients was selected from the New Zealand Intensive Medicines Monitoring Programme’s (IMMP) patient cohorts for each drug. Questionnaires sent to prescribers requested information on indications, risk factors for ischaemic heart disease, lipid profiles with changes during treatment and reasons for stopping therapy.

Results

80% of prescribers replied and 83% of these contained useful information. The three groups were similar for age, sex and geographical region, but significantly more patients on bezafibrate had diabetes and/or hypertension than those on gemfibrozil or simvastatin. After treatment and taking the initial measure into account, the changes in serum lipid values were consistent with those generally observed, but with gemfibrozil being significantly less effective than expected. More patients (15.8%) stopped gemfibrozil because of an inadequate response compared with bezafibrate (5.4%) and simvastatin (1.6%). Gemfibrozil treatment was also withdrawn significantly more frequently due to a possible adverse reaction compared with the other two drugs.

Conclusions

In normal clinical practice in New Zealand gemfibrozil appears less effective and more frequently causes adverse effects leading to withdrawal of treatment than either bezafibrate or simvastatin.

Keywords: treatment outcomes, normal clinical practice, postmarketing surveillance, gemfibrozil, bezafibrate, simvastatin, antihyperlipidaemic agents

Introduction

In an investigation of lipid lowering agents, Andrade and colleagues [1] observed that findings from clinical trials may not be applicable in non-trial settings. Because of current interest in treating dyslipidaemia as a means of reducing the risk of ischaemic heart disease and the lack of data outside of controlled clinical trials, we have used data from the New Zealand (NZ) Intensive Medicines Monitoring Programme (IMMP) to compare, in normal clinical practice, the use of the three newer lipid lowering agents that have, until recently, been the only ones readily available in NZ. A Medline search from January 1987 to May 1997 including the terms ‘primary care’, ‘general practice’, or ‘clinical practice’ and ‘lipid lowering’ for all three drugs individually failed to find any further relevant studies.

The lipid lowering agents bezafibrate, gemfibrozil and simvastatin, were intensively monitored for adverse events in the NZ IMMP for 5 years (January 1989 until February 1994). This is a scheme of early post marketing surveillance designed to detect new adverse reactions to medicines [2]. In brief, a near complete record is obtained of all NZ patients. Prescription records are received from dispensing pharmacists in community and hospital pharmacies over the whole country. Details include the names and addresses of patients who have been prescribed the drugs currently being monitored, together with prescription details and the prescribers’ names and addresses. In regions comprising 25% of the country this is done by using duplicate prescriptions for IMMP drugs with pharmacists sending the duplicates to the adverse reactions centre in Dunedin: the remainder send computer generated lists. Adverse events are reported by a combination of prescription follow-up questionnaires and spontaneous reporting.

If further information is required on use or adverse event profiles or if a cluster of events signals a possible reaction to a drug, additional questionnaires may be sent to prescribers and, in some cases, directly to patients. The scheme has resulted in the early detection or confirmation of several adverse drug reactions [3–5] and has also demonstrated that some drug-event associations are unlikely to be adverse reactions [6].

The data for this study were taken from a trial run of a study to assess a signal of an adverse reaction (increased rate of angina with bezafibrate, unpublished). The results of the pilot indicated confounding by indication as the reason for the excess of angina with bezafibrate.

Methods

Patients prescribed bezafibrate, gemfibrozil or simvastatin were randomly selected from the complete IMMP cohorts numbering 10 226, 4541 and 7588 respectively and the prescribers were identified to enable a survey using written questionnaires. Where possible, the prescribers selected were the general practitioners responsible for the continuing care of the patients.

Six hundred patients (200 on each lipid lowering drug) were selected for this investigation. Clerical error reduced the simvastatin cohort to 197 with the target 200 questionnaires being sent for bezafibrate and gemfibrozil. Patients prescribed bezafibrate were randomly selected from each region of NZ in proportion to total prescribing nationally and then patients for gemfibrozil and simvastatin were matched with these for region and gender. Patients were matched for region to allow for differences in prescribing patterns, ethnicity and monitoring methods. There were insufficient with known age to use this in matching.

A questionnaire was posted to each patient’s doctor. It was designed to elicit information on and allow comparisons of: indication; lipid values; dose; duration of therapy; any concomitant drug therapy used; risk factors for ischaemic heart disease. This included a request for patient data on age, gender, weight and height, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypothyroidism. Outcome measurements were changes in serum lipid values and withdrawals from therapy. The reasons for withdrawal were requested. To improve the response rate, a follow-up letter and second questionnaire was sent to doctors from whom no reply was received after approximately 2 months.

Collation and analysis of data were performed using SAS. Chi squared tests were used to compare the categorical variables. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated from weight and height.

The lipid values were logarithmically transformed before analysis. Analysis of variance was used to derive the mean of the ratio of the before and after measures for each treatment. These are presented with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Regression analysis adjusting for the initial value for each measure was used to examine the ratio of the changes in bezafibrate and simvastatin compared with gemfibrozil. The ratios of the differences and their 95% CI are shown.

Nationwide ethical approval from the NZ Regional Health Authority Human Ethics Committees was granted for this study.

Results

Of the 597 questionnaires sent 476 (79.7%) were returned. Three hundred and ninety-four (66% of the total sent) contained information that was sufficiently complete to allow analysis: bezafibrate 130; gemfibrozil 139; simvastatin 125).

Demographic features

As expected, more males were prescribed lipid lowering drugs and this was consistent for the three drug groups (bezafibrate 54%; gemfibrozil 58%; simvastatin 57% males). There were no significant differences in the mean ages of patients in each group (bezafibrate =57.5 years; gemfibrozil =59.6 years; simvastatin =56.3 years). The regional distribution of the valid responses was similar for all three drugs. The mean duration of therapy with bezafibrate was longer than that with gemfibrozil and simvastatin; bezafibrate 1.5 years (s.d. =1.44); gemfibrozil 1.0 year (s.d. =1.08) and simvastatin 1.0 year (s.d. =1.03).

Reasons for using lipid lowering drugs

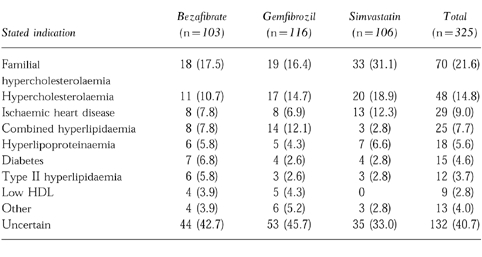

Indications for use are shown in Table 1. An open ended question requested a ‘specific diagnosis’. There were 325 (82.5%) responses to this question. Many doctors were uncertain of the specific diagnosis but did indicate the most obvious reason for drug use. Data from a separate question about pre-existing angina showed no statistically significant difference in prevalence among groups (bezafibrate 54, 43%; gemfibrozil 52, 45%; simvastatin 63, 53%).

Table 1.

Specific diagnosis or reason for use of bezafibrate, gemfibrozil or simvastatin. Figures are numbers of responses to this question (%).

Risk factors for ischaemic heart disease

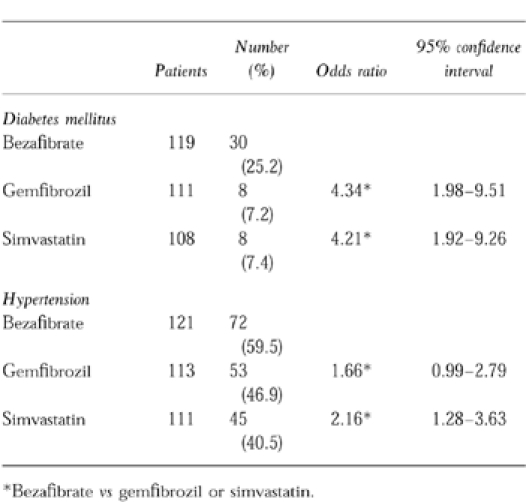

Statistically significant differences were observed in two risk factors (Table 2). Bezafibrate was prescribed for 30 (25.2%) patients with diabetes mellitus compared with gemfibrozil 8 (7.2%) and simvastatin 8 (7.4%) with answers to this question totalling 119, 111 and 108 respectively. There were also more hypertensive patients in the bezafibrate group (72, 59.5%) compared with gemfibrozil (53, 46.9%) and simvastatin (45, 40.5%, totals were 121, 113 and 111 respectively). There were no statistically significant differences for cigarette smoking, hypothyroidism or mean BMI for males or females.

Table 2.

Differences in risk factors for ischaemic heart disease.

Concomitant medications

There were 62 different drugs recorded as used in combination with the lipid lowering agents. The most common types were β-adrenoceptor blockers (54 patients), aspirin (34), and nitrates (32). The distribution of concomitant medications between the three lipid lowering agents was similar and there were no differences that might confound the interpretation of changes in lipid levels.

Effects of lipid lowering drugs on lipid levels

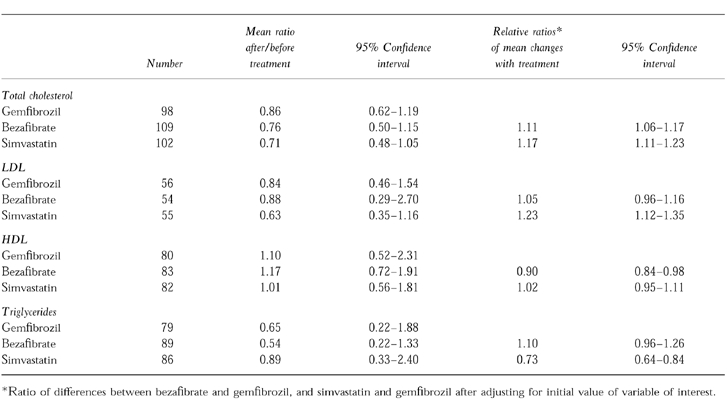

The ratios of the changes and their 95% CI of gemfibrozil to simvastatin and bezafibrate are presented in Table 3. Regression analysis adjusting for the initial values showed that decreases in total cholesterol for patients taking gemfibrozil were significantly less than for those using either bezafibrate or simvastatin. Although the ratio of change was greatest for bezafibrate, the relative ratio of the change was less because of differences in the initial value. The reduction in low density lipoproteins (LDL) for those on simvastatin was significantly greater than that for gemfibrozil.

Table 3.

Comparison of changes in serum lipid values: gemfibrozil vs bezafibrate and simvastatin.

Bezafibrate increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels significantly more than either gemfibrozil or simvastatin. The reduction in serum triglycerides was significantly less for simvastatin than for either of the other two agents.

Reasons for stopping treatment with lipid lowering drugs

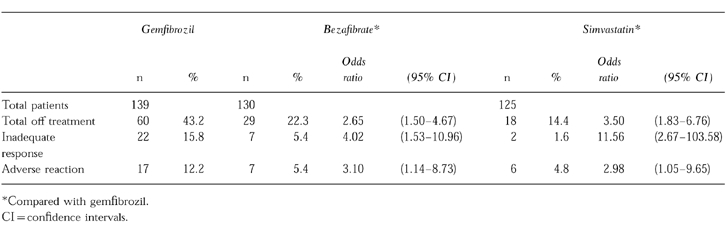

There were significant differences between the three drugs for cessation of therapy (Table 4). The greatest difference was for inadequate response where 22 (15.8%) patients stopped gemfibrozil compared with seven (5.4%) for bezafibrate (OR =4.02; 95% CI =1.53–10.96) and two (1.6%) for simvastatin (OR =11.56; CI =2.67–103.58).

Table 4.

Main reasons for cessation of therapy with lipid lowering drugs.

Gemfibrozil treatment was also stopped more frequently (n =17, 12.2%) due to a possible adverse reaction compared with bezafibrate (7, 5.4%) and simvastatin (6, 4.8%). Approximately half of the adverse reactions leading to withdrawal of gemfibrozil were gastrointestinal. Overall, the total cessation rate for gemfibrozil was significantly greater than bezafibrate (OR =2.65; 95% CI =1.50–4.67) and simvastatin (OR =3.50; CI =1.83–6.76).

Discussion and conclusions

This retrospective study on randomised and matched samples of the IMMP cohorts for bezafibrate, gemfibrozil and simvastatin should provide a reliable indication of the short term outcome of treatment in terms of efficacy in normalising abnormal lipid values and their tolerability in normal clinical practice in NZ. It was designed to evaluate a signal of an adverse reaction with bezafibrate and the design included comparison of indications for treatment, the presence of risk factors for ischaemic heart disease, diagnosis and severity of lipid disorder and some outcomes of therapy. Therefore, although the study was not specifically designed to compare efficacy of treatment, the methodology is appropriate.

The results are likely to reflect outcomes in most other developed countries and are consistent where comparisons are possible, with a study in non-trial settings in the USA by Andrade et al. [1]. Because of its short duration and low numbers, our NZ study cannot address the clinical outcomes of lipid related mortality and rates of myocardial infarction and this was not one of the objectives. However, analyses of randomised trials of cholesterol lowering have consistently shown that for every 10% relative reduction in blood cholesterol there is an approximate 15–20% relative reduction in coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity after about 5 years of treatment [7, 8] and a study on the effects of the drugs on lipid values is therefore a useful surrogate for clinical outcome.

For reasons of differences in patient selection and the many confounding variables in community practice that are often controlled for in clinical trials, results may differ between the two. This study and that of Andrade in the United States is therefore helpful in understanding what is happening in non-trial settings, which is the important end issue. Andrade’s study examined discontinuation rates of antihyperlipidaemic drugs in primary care compared with those of randomised clinical trials. The drugs included bile acid sequestrants, niacin, gemfibrozil and lovastatin. For all except lovastatin the risk of discontinuation was substantially higher in primary care than in the trials. The comparable rate of drug discontinuation of 28% for gemfibrozil was similar to our IMMP study with a rate of 32% and the rates for withdrawals because of inefficacy were 14.8% and 15.8%, and for adverse reactions were 9.5% and 12.2%, respectively. Lovastatin, the representative of the HMG CoA reductase inhibitors in the American study, had similar gross rates of discontinuation for lack of efficacy to that of simvastatin in the IMMP (2.4% and 1.6% respectively) and also for adverse effects (6.5% and 4.8% respectively).

In the IMMP study it was expected that the two fibrates would perform similarly. However, while bezafibrate and gemfibrozil reduced LDL and triglycerides to a similar extent, bezafibrate was significantly better than gemfibrozil at reducing total cholesterol and increasing HDL. Patients on gemfibrozil had more withdrawals because of inefficacy and this was consistent with the differences observed in changes of lipid values. Results are variable in trials comparing their efficacy [9, 10, 11]. For gemfibrozil it is often not possible to predict those patients who will respond well and the response has been noted to be variable [11]. One study, a randomised trial of 59 non-diabetic patients with type II hyperlipoproteinaemia, showed that bezafibrate had significantly fewer adverse reactions compared with gemfibrozil as well as better efficacy at lowering serum total cholesterol, LDL and blood glucose [12]. The IMMP study showed that withdrawal of therapy overall was a significantly greater problem with gemfibrozil compared with bezafibrate and simvastatin and this included significantly more withdrawals because of adverse reactions. As expected, simvastatin compared favourably with the fibrates in lowering total cholesterol and LDL. It also had the lowest withdrawal rate because of adverse reactions.

The significantly greater prevalence of diabetes mellitus amongst patients prescribed bezafibrate has not been previously demonstrated in practice. The use of fibrates in diabetic patients reflects a logical choice as they frequently have high serum triglyceride and low HDL levels as well as elevated total cholesterol levels. There is conflicting evidence as to the comparative effects of bezafibrate and gemfibrozil on glucose tolerance and insulin resistance, but it seems to weigh in favour of bezafibrate [9, 10] and the preferred use of bezafibrate in the presence of diabetes mellitus by NZ doctors reflects this opinion. The higher rate of hypertension in patients prescribed bezafibrate may result from the greater prevalence of diabetes. The significant excess of new or worsening angina reported during monitoring which stimulated this study, was probably due to the confounding influence of these two risk factors for ischaemic heart disease.

In this comparison of the three lipid lowering agents, the recognisable biases would favour gemfibrozil. The presence of more diabetes mellitus in the bezafibrate group would tend to produce a more unfavourable outcome. The mean duration of therapy for patients on bezafibrate was also 50% greater than gemfibrozil and simvastatin. In addition, the indications for use of simvastatin in NZ were restricted to patients with more severe lipid related disease and those who had not responded satisfactorily to the fibrates. These biases make the observed differences of reduced efficacy and higher rate of withdrawals and adverse reactions with gemfibrozil even more significant.

The fibrates still have a significant place in the treatment of dysplipidaemia in modern clinical practice and this is reflected in drug usage figures. Although the use of the HMG CoA reductase inhibitors has increased markedly, the use of the fibrates has not declined in England. Figures from the Prescription Pricing Authority (PPA) of national trends in the usage of fibrates show a steady increase to December 1996 with a levelling off until the latest available figures at September 1997 (Ferguson JJ, personal communication, 1998). As referred to above, they are a logical choice in treating the high serum triglyceride and low HDL in diabetes mellitus [13]. High levels of plasma fibrinogen are being increasingly recognised as an important cardiovascular risk factor and fibrates have been reported to be the most effective drugs in lowering fibrinogen [14]. Should active lowering of elevated fibrinogen become established in clinical practice, the use of fibrates may increase in future. Because bezafibrate is currently regarded as the most effective fibrate in lowering fibrinogen, it is likely that this drug will become the drug of choice for this indication. However, other fibrates (such as gemfibrozil) are also effective and may also be used in future for this purpose. Statin-fibrate combined treatment is also an option in difficult to manage dyslipidaemias. Earlier this was discouraged because of the perceived increased risk of myositis or rhabdomyolysis [15], However, a review of 21 clinical trials of statin-fibrate combined treatment involving a total of 486 patients concluded that the combinations were ‘proven to be effective and safe’ [16]. Type II hyperlipidaemia was the most common indication. Another reason for current use of fibrates is control of pharmaceutical expenditure. The fibrates are cheaper and in NZ the use of statins is restricted because of this.

The data from the PPA show that the fibrate most commonly used in England is bezafibrate with gemfibrozil maintaining a small, but fairly constant share which is however exceeded by ciprofibrate and fenofibrate. These latter two are not available in NZ where IMMP data showed that gemfibrozil usage was approximately half that of bezafibrate. Bezafibrate is not approved for marketing in Australia where gemfibrozil is the most commonly used fibrate (Boyd I, personal communication, 1998). Neither is bezafibrate used in the United States, but gemfibrozil is available and widely used (Chen M, personal communication, 1998). In the Helsinki Heart Study, a randomised double-blind trial, gemfibrozil 600 mg twice daily reduced the incidence of coronary heart disease after 5 years by 34% compared with placebo-treated patients [17]. There is less evidence of cardiovascular benefit to support the use of bezafibrate, but in a study of 92 young male survivors of myocardial infarction, the Bezafibrate Coronary Atherosclerosis Intervention Trial, bezafibrate reduced the rate of progression of atherosclerotic lesions and the rate of coronary events [18]. Another much larger study, the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention trial in 300 men is not yet reported [19].

As described, the indications are that the fibrates will continue to be used extensively for specific indications in the foreseeable future and it is clear that bezafibrate and gemfibrozil are still widely used in spite of a marked increase in the use of statins. This IMMP study in a non-trial setting, which showed gemfibrozil was less effective than bezafibrate in raising serum levels of HDL-cholesterol and lowering total cholesterol and resulted in more withdrawals for adverse reactions, raises the question of the suitability of gemfibrozil as a first choice fibrate.

Acknowledgments

We thank the doctors who assisted with follow up of their patients and our Data Manager Mrs Janelle Ashton. The study was financed from research funds of the Department of Pharmacology. Mrs Williams is supported by the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

References

- 1.Andrade SE, Walker AM, Gottlieb LK, et al. Discontinuation of antihyperlipidemic drugs: do rates reported in clinical trials reflect rates in primary care settings? N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1125–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coulter DM. The New Zealand Intensive Medicines Monitoring Programme. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 1998;7:79–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1557(199803/04)7:2<79::AID-PDS330>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulter DM, Edwards IR. Mianserin and agranulocytosis in New Zealand. Lancet. 1990;336:785–787. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)93248-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulter DM, Edwards IR. Cough associated with captopril and enalapril. Br Med J. 1987;294:1521–1523. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6586.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coulter DM, Edwards IR, Savage RL. Survey of neurological problems with amiodarone in the New Zealand Intensive Medicines Monitoring Programme. NZ Med J. 1990;103:98–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulter DM. Eye pain with nifedipine and disturbance of taste with captopril: a mutually controlled study showing a method of postmarketing surveillance. Br Med J. 1988;296:1086–1088. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6629.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival (4S) Study. Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shepherd J, Cobbe S, Ford I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolaemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goa KL, Barradell LB, Plosker GL. Bezafibrate: An update of its pharmacology and use in the management of dyslipidaemia. Drugs. 1996;52:725–753. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652050-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spencer CM, Barradell LB. Gemfibrozil: A reappraisal of its pharmacological properties and place in the management of dyslipidaemia. Drugs. 1996;51:982–1018. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199651060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Todd PA, Ward A. Gemfibrozil: A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in dyslipidaemia. Drugs. 1998;11:293–303. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198836030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kremer P, Marowsky C, Jones C, Acacia E. Therapeutic effects of bezafibrate and gemfibrozil in hyperlipoproteinaemia Type IIa and IIb. Cur Med Res Opin. 1989;11:293–303. doi: 10.1185/03007998909115212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oki JC. Dyslipidaemias in patients with diabetes mellitus: classification and risks and benefits of therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 1995;15:317–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fowkes FGR. Fibrinogen and cardiovascular disease in clinical practice. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(Suppl A):60–63. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/16.suppl_a.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce R, Wysowsky DK, Gross TP. Myopathy and rhabdomyolysis associated with lovastatin-gemfibrozil combination therapy. J Am Med Ass. 1990;264:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shviro I, Leitersdorf E. The patient at risk: who should we be treating? Br J Clin Pract. 1996;77A:24–27. Symposium Supplement. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, et al. Helsinki Heart Study: primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidaemia. Safety of treatment, changes in risk factors, and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1237–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711123172001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ericsson C-G, Hamsten A, Nilsson J, Grip L, Svane B, de Faire U. Angiographic assessment of effects of bezafibrate on progression of coronary artery disease in young male postinfarction patients. Lancet. 1996;346:849–853. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldbourt U, Behar S, Reicher-Reiss H, et al. Rationale and design of a secondary prevention trial of increasing serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and reducing triglycerides in patients with clinically manifest atherosclerotic heart disease (the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention Trial) Am J Cardiol. 1993;71:909–915. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90905-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]