Abstract

Aims

To determine the effects of mibefradil on the metabolism in human liver microsomal preparations of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin, cerivastatin and fluvastatin.

Methods

Metabolism of the above five statins (0.5, 5 or 10 μm), as well as of specific CYP3A4/5 and CYP2C8/9 marker substrates, was examined in human liver microsomal preparations in the presence and absence of mibefradil (0.1–50 μm).

Results

Mibefradil inhibited, in a concentration-dependent fashion, the metabolism of the four statins (simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin) known to be substrates for CYP3A. The potency of inhibition was such that the IC50 values (< 1 μm) for inhibition of all of the CYP3A substrates fell within the therapeutic plasma concentrations of mibefradil, and was comparable with that of ketoconazole. However, the inhibition by mibefradil, unlike that of ketoconazole, was at least in part mechanism-based. Based on the kinetics of its inhibition of hepatic testosterone 6β-hydroxylase activity, mibefradil was judged to be a powerful mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP3A4/5, with values for Kinactivation, Ki and partition ratio (moles of mibefradil metabolized per moles of enzyme inactivated) of 0.4 min−1, 2.3 μm and 1.7, respectively. In contrast to the results with substrates of CYP3A, metabolism of fluvastatin, a substrate of CYP2C8/9, and the hydroxylation of tolbutamide, a functional probe for CYP2C8/9, were not inhibited by mibefradil.

Conclusions

Mibefradil, at therapeutically relevant concentrations, strongly suppressed the metabolism in human liver microsomes of simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin through its inhibitory effects on CYP3A4/5, while the effects of mibefradil on fluvastatin, a substrate for CYP2C8/9, were minimal in this system. Since mibefradil is a potent mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP3A4/5, it is anticipated that clinically significant drug–drug interactions will likely ensue when mibefradil is coadministered with agents which are cleared primarily by CYP3A-mediated pathways.

Keywords: CYP3A, drug interactions, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, in vitro metabolism, mibefradil, statins

Introduction

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, or ‘statins’, are used widely for the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia [1], and act through inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase, the rate limiting enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis. Mibefradil (Posicor™)*is a newly introduced calcium channel blocker intended for the long-term treatment of patients suffering from hypertension [2]. Recently, cases of myopathy, including rhabdomyolysis, have been reported in patients with hypertension who received simvastatin concomitantly with mibefradil [3]. Myopathy or rhabdomyolysis is a rare side-effect common to all statins and usually is associated with high levels of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitory activity. Since simvastatin is known to be metabolized extensively by cytochrome P-450 3A (CYP3A) in humans [4], it appeared possible that coadministration of mibefradil elevated simvastatin plasma levels via inhibition of the CYP3A enzyme system, and thereby precipitated the observed myopathies. Among marketed statins, lovastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin have been reported to be metabolized primarily by CYP3A enzymes [5–7], and thus all have a potential to interact with mibefradil at the level of drug metabolism.

The present study was designed to investigate possible underlying mechanisms for the observed and potential interactions between mibefradil and statins, and comprised a series of in vitro metabolism studies of statins in human liver microsomal preparations in the presence and absence of mibefradil. In total, five statins were studied, including those reported to serve as substrates for CYP3A (simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin) [4–7] or CYP2C8/9 (fluvastatin) [8]. The effects of mibefradil on drug metabolizing enzyme activities then were confirmed and characterized using known P450 marker substrates. Finally, since mibefradil was found to be a potent inhibitor of CYP3A in vitro, its inhibitory effects were compared with those of ketoconazole, a known in vitro and in vivo inhibitor of cytochrome P-450 enzymes in humans [9–11].

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

[14C]-Simvastatin (16 mCi mmol−1), simvastatin and lovastatin were synthesized at Merck Research Laboratories. Atorvastatin, cerivastatin and mibefradil were extracted from commercial sources and their identity and purity was confirmed by IR and NMR spectroscopy. Fluvastatin was a generous gift from Sandoz (East Hanover, NJ). Markers and chemical inhibitors of cytochrome P-450 enzymes were obtained from the following suppliers: testosterone, tolbutamide, troleandomycin and quinidine—Sigma (St Louis, MO), 6β-hydroxytestosterone—Steraloids (Wilton, NH), 3-methylhydroxytolbutamide and sulphaphenazole—Ultrafine (Manchester, England), and ketoconazole—Research Diagnostics, Inc. (Flanders, NJ). Human liver microsomes (pooled from 10 subjects) were purchased from the International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine (Exton, PA).

Effects of mibefradil on metabolism of statins

A typical incubation mixture, in a final volume of 0.5 ml, contained 0.05–0.25 mg liver microsomal protein, 50 μmol sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 5 μmol MgCl2, 0.5 μmol NADPH and 5 nmol substrate ([14C]-simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin or cerivastatin). In all experiments, mibefradil (0.05–25 nmol in 8 μl acetonitrile; 0.1–50 μm final concentrations) or acetonitrile (8 μl, control) either was coincubated with substrates or preincubated with liver microsomes and NADPH for 30 min at 37° C before adding the substrates. Incubations were conducted at 37° C and were terminated after 5 min for simvastatin and lovastatin, after 12 min for atorvastatin and after 18 min for cerivastatin, by the addition of 2 ml acetonitrile. Preliminary experiments showed that the final statin concentration (10 μm) used for these studies was below or comparable with the respective Km value, and that the rates of formation of all metabolites were linear during these incubation periods. The acetonitrile extracts were evaporated to dryness and reconstituted for analysis by a high-performance liquid chromatography (h.p.l.c.) method described below.

Metabolic studies with fluvastatin were conducted similarly, but in an incubation volume of 0.2 ml, and with 0.1 and 1 nmol fluvastatin (final concentrations of 0.5 and 5 μm, respectively). The incubations were terminated after 25 min by the addition of 0.2 ml acetonitrile. Following centrifugation, the supernatants were analysed directly by h.p.l.c. (see below).

Effects of mibefradil on P-450 activities

Activities of CYP3A4/5 (testosterone 6β-hydroxylation) and CYP2C8/9 (tolbutamide 3-methylhydroxylation) were determined using published assays [12], and employed marker substrate concentrations of 50 μm-testosterone and 100 μm tolbutamide. Mibefradil was either coincubated with the marker substrate before the reaction was initiated with NADPH (1 mm) or preincubated with liver microsomes and NADPH (1 mm) for 30 min at 37° C before adding the marker substrate. The substrate concentrations used were comparable to their Km values [12]. In experiments with testosterone, the mixture also was preincubated in the presence and absence of NADPH for various times during a 45-min incubation period before assaying for remaining CYP3A activity.

Kinetics of inactivation of CYP3A

Studies on the kinetics of CYP3A4/5 inactivation were performed using the testosterone 6β-hydroxylase assay at a high concentration of testosterone (250 μm), in order to minimize the possibility of competitive inhibition by mibefradil. Human liver microsomes were preincubated with NADPH (1 mm) in the presence of 0, 0.5, 1, 2 and 5 μm mibefradil, in a final volume of 0.1 ml, for 0, 0.5, 2.5, 5, 10 and 15 min at 37° C. Subsequently, the reaction mixtures were diluted to 0.5 ml for the determination of testosterone 6β-hydroxylase activity.

Effects of P-450 inhibitors on metabolism of statins

Metabolism of statins also was examined in the presence of known inhibitors of cytochrome P-450, namely ketoconazole (1 μm) and/or sulphaphenazole (100 μm). At these concentrations, ketoconazole has been shown to be a potent selective inhibitor of CYP3A [9, 10] and sulphaphenazole a selective inhibitor of CYP2C8/9 [13]. In these experiments, both sulphaphenazole and ketoconazole were coincubated with the statins.

In vitro metabolism of mibefradil

Metabolism of mibefradil also was examined in vitro in order to determine a partition ratio for inhibition of CYP3A. The reaction mixture, in a final volume of 0.5 ml, contained 0.25 mg liver microsomal protein, 50 μmol sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 5 μmol MgCl2, 0.5 μmol NADPH, and 0.25 or 1 nmol mibefradil. The mixture was incubated for varying times up to 30 min at 37° C before the reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 ml acetonitrile. The acetonitrile extracts were evaporated to dryness and reconstituted for analysis by h.p.l.c. A preliminary study indicated that NADPH-independent hydrolysis of mibefradil was minimal (< 15% of the starting concentration) under the incubation conditions used.

Analytical procedures for statins and mibefradil

Simvastatin and lovastatin were analysed using published h.p.l.c. methods [4, 5], with minor modifications. In brief, samples were chromatographed on a C8-Zorbax Rx column (250×4.6 mm, 5 μm), preceded by a C8 guard column, with a linear gradient of acetonitrile and 0.05% phosphoric acid (33% to 75% acetonitrile in 15 min). Cerivastatin and its metabolites were separated on a C18-Zorbax Rx (150×4.6 mm, 5 μm), with a linear gradient of acetonitrile and 2 mm perchloric acid (15% to 60% acetonitrile in 15 min). Atorvastatin and fluvastatin were chromatographed on a C18 column (Symmetry, Waters, 150×4.6 mm, 5 μm), with a linear gradient of acetonitrile and 0.05% phosphoric acid (30% to 60% acetonitrile in 8 min). The effluent was monitored using a u.v. detector (set at 240 nm and 270 nm for simvastatin and lovastatin, 240 nm for atorvastatin, or 283 nm for cerivastatin), an on-line radioactivity detector ([14C]-simvastatin), or a fluorescence detector (λex 305 nm and λem 380 nm for fluvastatin). For all compounds, standard curves showed satisfactory linearity and precision (< 15% coefficient of variation). The limits of assay detection were 5 pmol (on column) for simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin, and 0.2 pmol (on column) for fluvastatin.

Identification of statin metabolites was accomplished by using liquid chromatography (HP-1050 gradient system, Hewlett Packard, San Fernando, CA)-tandem mass spectrometry (Finnigan MAT LCQ ion trap mass spectrometer, Finnigan-MAT, San Jose, CA). Separation of the metabolites was carried out on a Betasil C18 column (2×150 mm, 5 μm) with a linear gradient of ACN and 0.1% formic acid (30% ACN to 80% ACN in 20 min), delivered at a constant flow rate of 0.2 ml min−1. Mass spectral analyses were performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) in the positive ion (lovastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin) and negative (fluvastatin) mode, set at 4 kV, with the heated capillary temperature set at 230° C.

Mibefradil was quantified by h.p.l.c. on a C8-Zorbax Rx column (250×4.6 mm, 5 μm), preceded by a C8 guard column, with a linear gradient of acetonitrile and 0.05% phosphoric acid (14% to 60% acetonitrile in 7 min) and a fluorescence detector (λex 270 nm and λem 300 nm).

Data analysis

Metabolism of each statin was measured either in terms of consumption of parent compound (total metabolism) or formation of its metabolites. The effects of mibefradil on metabolism of the statins were expressed as percentages of total substrate consumed or metabolites formed in the presence of mibefradil relative to the corresponding values obtained in the absence of mibefradil (control) on the same day. The concentration of mibefradil producing a 50% decrease in the metabolism of statins or marker P-450 activities (IC50) was determined using nonlinear regression analysis (PCNONLIN, Scientific Consulting, Cary, NC), based on the following relationship:

where E and Emax are the effects measured in the presence of mibefradil (at concentration C) and in the absence of mibefradil, respectively. Only the estimates with standard errors of < 25%, which were judged to be satisfactory, were reported.

The kinetics of CYP3A4/5 inactivation were determined using standard procedures [14]. The initial rate constant for inactivation at each concentration of mibefradil was estimated from the initial slope of the loglinear regression line of the CYP3A activity remaining and the preincubation time profile. Kinetic parameters (Kinactivation and Ki) for the inactivation of 6β-testosterone hydroxylase activity were then estimated from the reciprocal plot of the rate constants for inactivation vs the respective mibefradil concentrations. The partition ratio then was estimated from the initial turnover rate of mibefradil at 0.5 μm relative to the inactivation rate constant of 6β-testosterone hydroxylase activity at the same inactivator concentration.

Results

Metabolism of statins in human liver microsomes

As reported previously [4, 5], simvastatin and lovastatin were found to undergo metabolism to several products, including the two major metabolites 3′-hydroxy-and 6β-exomethylene-lovastatin/simvastatin. With the use of a radioactivity detector, 3′,5′-dihydrodiol simvastatin, a major metabolite lacking UV absorption at 240 nm [4], also was observed in incubation products. In the case of atorvastatin, two metabolites were detected which, based on analysis by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, proved to be products of hydroxylation of atorvastatin at the phenylaminocarbonyl side chain [15]. Similarly, cerivastatin underwent metabolism in liver microsomal preparations to the known products of O-demethylation (major) and hydroxylation (minor) [7]. Finally, fluvastatin was shown to undergo metabolism to one major product, identified as a hydroxylated derivative on the indole moiety; this same product has been noted previously as a principal metabolite found in vivo [16].

Effects of mibefradil on metabolism of statins

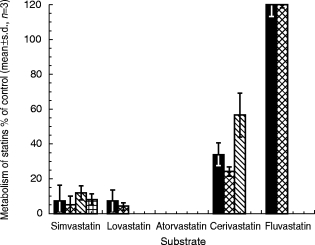

The effects of mibefradil on both total metabolism of the statins (measured in terms of substrate consumption) and the formation of metabolites are shown in Figure 1. In all cases, similar results were observed between the two measurements, suggesting that the metabolites detected in this study accounted satisfactorily for the disappearance of the respective parent. In the case of cerivastatin, however, the degree of inhibition of the hydroxylation pathway appeared to be less than the effect of mibefradil on formation of the demethylated metabolite or the total metabolism (Figure 1). These results suggested that the primary enzyme(s) involved in the formation of the two metabolites of cerivastatin might not be identical, consistent with a previous report [7].

Figure 1.

Effects of mibefradil (2 μm) on the consumption of statins or the formation of statin metabolite in human liver microsomal preparations. Experiments were carried out following preincubation of mibefradil with human liver microsomes in the presence of NADPH (1 mm) at 37° C for 30 min prior to the addition of statins. M1 and M2 of simvastatin and lovastatin denote 3′-hydroxy-and 6β-exomethylene products, respectively; M3 of simvastatin denotes the 3′,5′-dihydrodiol metabolite; M1 and M2 of atorvastatin and M1 of fluvastatin refer to hydroxylated products; and M1 and M2 of cerivastatin denote demethylated and hydroxylated metabolites, respectively. Results are expressed as a fraction of the corresponding metabolism in the absence of mibefradil. Under these conditions, mibefradil inhibited atorvastatin metabolism completely. ▪ total metabolism,  M1,

M1,  M2,

M2,  M3.

M3.

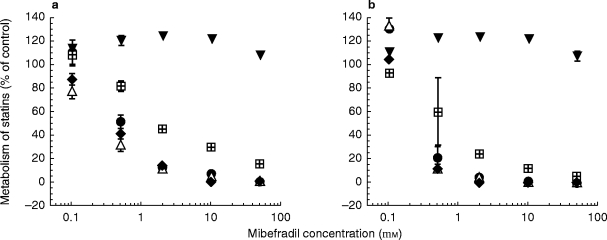

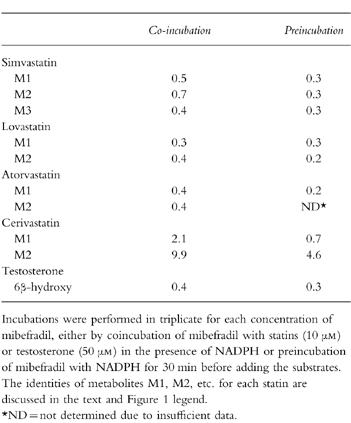

With the single exception of fluvastatin, mibefradil inhibited the metabolism of all statins, in a concentration-dependent fashion (Figure 2a,b). Over the tested concentration range, comparable degrees of inhibition were evident on the metabolism of simvastatin, lovastatin and atorvastatin, and slightly less for cerivastatin (Figure 2a,b). In the experiments conducted by coincubating mibefradil with the above four statins, IC50 values of mibefradil ranged from 0.3 to 2 μm for all major metabolites (Table 1), while the observed degree of inhibition increased when mibefradil was first incubated with NADPH for 30 min prior to the addition of statins (Figure 2b). The estimated IC50 values for all metabolites in these preincubation experiments generally were lower than those obtained by simple coincubation (Table 1). This apparent NADPH-dependent CYP3A inhibition by mibefradil suggests that mibefradil may be converted, at least in part, to a reactive intermediate which contributes to the overall inhibition of statin metabolism.

Figure 2.

Concentration-dependent inhibitory effects of mibefradil on metabolite formation for all five statins (a) following co-incubation of statins and mibefradil with human liver microsomes and NADPH, or (b) following preincubation of mibefradil with human liver microsomes in the presence of NADPH at 37° C for 30 min before metabolism of statins was initiated. Shown in the Figures are results (mean±s.d., n = 3) obtained for the 3′-hydroxy simvastatin, the 3′-hydroxy lovastatin, a hydroxylated product of atorvastatin or fluvastatin, and the demethylated metabolite of cerivastatin. • simvastatin, ▵ lovastatin, ♦ atorvastatin,  cerivastatin, ▾ fluvastatin.

cerivastatin, ▾ fluvastatin.

Table 1.

Inhibitory effects of mibefradil, expressed as IC50 values (μm), on the metabolite formation of simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin, cerivastatin and testosterone in human liver microsomal preparations.

The inability of mibefradil, with or without preincubation with NADPH, to inhibit the metabolism of fluvastatin (Figure 2a,b) indicates that fluvastatin does not undergo biotransformation by the same enzyme system that catalyses metabolism of the above four statins. Control experiments indicated that fluvastatin metabolism was inhibited markedly by sulphaphenazole, a selective inhibitor of CYP2C8/9 (data not shown). These results suggest that mibefradil is not an inhibitor of CYP2C8/9, and supports the view that fluvastatin is metabolized primarily by CYP2C8/9. In an earlier study [8], fluvastatin was shown to inhibit competitively CYP2C8/9 activity, in line with the present finding.

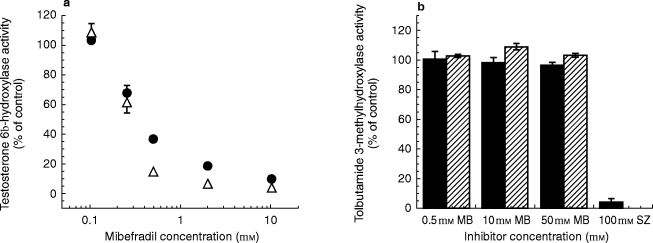

Effects of mibefradil on P-450 activities

Inhibitory effects of mibefradil on CYP3A4/5 and CYP2C8/9 activities were confirmed using the known marker metabolites 6β-hydroxytestosterone and 3-methylhydroxytolbutamide, respectively. As was observed with metabolism of the statins catalysed by CYP3A, concentration-dependent inhibition by mibefradil was observed for the conversion of testosterone to 6β-hydroxytestosterone (Figure 3a). The values for IC50 estimated in the coincubation and preincubation experiments also were in a comparable range to those observed for these four statins (Table 1). In agreement with the finding obtained earlier with fluvastatin (Figure 2a,b), tolbutamide 3-methylhydroxylase activity was not inhibited by mibefradil, with or without NADPH preincubation, but was suppressed almost completely by the CYP2C8/9 inhibitor sulphaphenazole (Figure 3b). These and the aforementioned results indicate clearly that mibefradil is an inhibitor of CYP3A4/5, but not of CYP2C8/9.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effects of mibefradil on human hepatic microsomal cytochrome P-450 activities (a) CYP3A4 and (b) CYP2C8/9. Results (mean±s.d., n = 3) were obtained following co-incubation of mibefradil and the marker substrates testosterone and tolbutamide, or following preincubation of mibefradil and NADPH at 37° C for 30 min before assaying for the P-450 activities. Control activities (nmol min−1 mg−1, mean±s.d.) for testosterone 6β-hydroxylase and tolbutamide 3-methylhydroxylase were 4.3±0.16 and 0.16±0.002 for co-incubation, and 4.5±0.12 and 0.10±0.003 for preincubation, respectively. MB = mibefradil, SZ = sulphaphenazole. •, ▪ co-incubation, ▵,  with NADPH-preincubation.

with NADPH-preincubation.

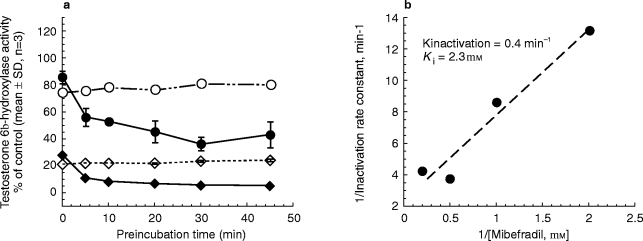

Kinetics of inactivation of CYP3A by mibefradil

The characteristics of mibefradil inhibition were examined further using testosterone 6β-hydroxylase as a marker for CYP3A4/5 activity. With NADPH-preincubation, mibefradil was found to inhibit CYP3A activity in both a time-and concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4a), a key feature of mechanism-based inhibition. From the reciprocal plot of the initial inactivation rate constant and mibefradil concentration (Figure 4b), values for the maximal inactivation rate constant (Kinactivation) and apparent Ki were estimated to be 0.4 min−1 and 2.3 μm, respectively. Subsequently, the partition ratio (defined as moles mibefradil metabolized per moles enzyme inactivated) at a mibefradil concentration of 0.5 μm was calculated to be 1.7. Although these kinetic parameters were obtained based on rather limited data (four different concentrations of mibefradil), they suggested that mibefradil is a fast acting and potent mechanism-based inhibitor.

Figure 4.

(a) Time-dependent loss of testosterone 6β-hydroxylase (CYP3A4) activity in the absence (○, 0.05 μm mibefradil, ◊ 2 μm mibefradil) or presence (• 0.5 μm mibefradil, ♦ 2 μm mibefradil) of NADPH (obtained at a testosterone concentration of 50 μm), and (b) double reciprocal plot of the initial CYP3A4 inactivation rate constant (obtained using 250 μm testosterone at mibefradil concentrations of 0.5, 2.5, 5 and 10 μm) and the corresponding mibefradil concentration.

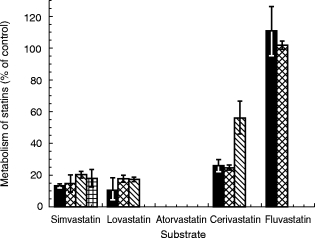

Effects of ketoconazole on metabolism of statins

Finally, experiments were conducted to compare the inhibitory effects of mibefradil on the metabolism of statins to those of the classic CYP3A inhibitor ketoconazole. With the exception of fluvastatin, ketoconazole (at 1 μm) inhibited appreciably (≈50–100%) the metabolism of each statin (Figure 5). The results were comparable with those obtained at 2 μm mibefradil (Figure 1). It should be noted that the IC50 value of ketoconazole for testosterone 6β-hydroxylase activity was ≈0.1 μm (data not shown), also in a close range to that of mibefradil (Table 1).

Figure 5.

Effects (mean±s.d., n = 3) of ketoconazole (1 μm) on the metabolism of statins (10 μm for lovastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin and 5 μm for fluvastatin). See Figure 1 for description of statin metabolites. Under these conditions, ketoconazole inhibited atorvastatin metabolism completely. ▪ total metabolism,  M1,

M1,  M2,

M2,  M3.

M3.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated clearly that mibefradil interacted strongly at the level of drug metabolism with those statins which are known to be substrates of CYP3A, but not with fluvastatin which is a substrate for CYP2C8/9. The inhibitory effects of mibefradil on CYP3A, but not CYP2C8/9 activity, also were confirmed using the known marker substrates testosterone (CYP3A4/5) and tolbutamide (CYP2C8/9), thus establishing that the inhibitory effects of mibefradil on the microsomal metabolism of simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin are due to the effects of this agent on CYP3A activity. The inhibition on CYP3A activity by mibefradil was found to be dependent on NADPH, time and mibefradil concentration, indicative of a mechanism-based inhibition. Considering that mibefradil underwent oxidative metabolism primarily by CYP3A (U.S. prescribing information for PosicorR, Roche Laboratories, Nutley, NJ)**, it is possible that a reactive metabolite of mibefradil, which inactivates CYP3A, also was formed by CYP3A. Based on the relatively rapid rate of inactivation (Kinactivation < 1 min−1, or t1/2≈2 min) and the relatively low partition ratio (< 2), mibefradil appeared to represent one of the most potent mechanism-based inhibitors of CYP3A known to date[[17] and references therein]. It should be noted that mibefradil also might reversibly inhibit CYP3A4/5 activity considering that the activity remaining in the absence of NADPH or at zero preincubation time with NADPH (approximation of reversible component) was ≈10% and 80% at 0.5 μm and 2 μm, respectively (Figure 4a). However, these values may be overestimated in view of the very rapid inactivation caused by mibefradil. In a preliminary study, the inhibition of CYP3A activity by mibefradil was mostly (≈90%) irreversible upon dialysis, in contrast to the inhibition by ketoconazole which was almost completely reversible (data not shown).

Considering that the therapeutic plasma concentrations of mibefradil (≈0.5–2.0 μm) [18] do not differ appreciably from those of ketoconazole (≈5 μm), and that ketoconazole causes a variety of clinically significant drug–drug interactions with agents whose metabolism is dependent on CYP3A4/5 [11], it may be anticipated that mibefradil will cause similar interactions in vivo. Moreover, since the CYP3A4/5 inhibition caused by mibefradil appears to be predominantly mechanism-based, it would be expected that the inhibitory effects of mibefradil in vivo would be longer lasting than those of ketoconazole, a pure reversible inhibitor of the enzyme. Erythromycin, a relatively weak mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP3A [9, 19, 20], has been reported recently to cause a modest, but significant interaction with cerivastatin in healthy volunteers (21% increase in AUC of cerivastatin and 60% decrease in AUC of the demethylated metabolite) [21]. Since mibefradil is a much more potent inhibitor than erythromycin, the in vivo inhibitory potential of mibefradil on the metabolism of cerivastatin and other CYP3A substrates would be expected to be much more pronounced than those of erythromycin.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that, in human liver microsomal preparations, mibefradil acts as a powerful mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP3A4/5. As a consequence, mibefradil strongly inhibited the metabolism of all statins which are substrates for the CYP3A enzyme system, i.e. simvastatin, lovastatin, atorvastatin and cerivastatin. In contrast, mibefradil does not inhibit CYP2C8/9 activity, and thus had little effect on the in vitro metabolism of fluvastatin, a CYP2C8/9 substrate. Based upon these findings, it is likely that mibefradil will cause significant drug–drug interactions in humans in vivo when coadministered with agents which are metabolized primarily through CYP3A4/5-dependent pathways.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs D. Dean and A. Jones for synthesis and purification of [14C]-simvastatin.

Footnotes

At the time of submission of this paper, the manufacturer of Posicor™ (Roche Laboratories, Nutley, NJ) announced (June 8, 1998) a voluntary withdrawal of mibefradil from the market world wide due to the potential for serious drug interactions.

U.S. Prescribing Information for POSICOR, Roche Laboratories, Nutley, NJ.

References

- 1.Pedersen TR, Berg K, Cook TJ, et al. Safety and tolerability of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin during 5 years in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2085–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clozel J-P, Osterrieder W, Kleinbloesem CH, et al. Ro 40–5967: a new non-dihydropyridine calcium antogonist. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 1991;9:4–17. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roche FDA announce new drug-interaction warnings for mibefradil. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1998;55:210. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/55.3.210a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prueksaritanont T, Gorham LM, Ma B, et al. In vitro metabolism of simvastatin in humans: Identification of metabolizing enzymes and effects of the drug on hepatic P-450s. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:1191–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang RW, Kari PH, Lu AHY, Thomas PE, Guengerich PF, Vyas KP. Biotransformation of lovastatin: IV. Identification of cytochrome P-450, 3A proteins as the major enzymes responsible for the oxidative metabolism of lovastatin in rat and human liver microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;290:355–361. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90551-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang BB, Siedlik PH, Smithers JA, Sedman AJ, Stern RH. Atorvastatin pharmacokinetic interactions with other CYP3A4 substrates: erythromycin and ethinyl estradiol. Pharm Res. 1996;13(9) Suppl:S437. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boberg M, Angerbauer R, Fey P, et al. Metabolism of cerivastatin by human liver microsomes in vitro: Characterization of primary metabolic pathways and cytochrome P450 isozymes involved. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:321–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Transon C, Leemann T, Dayer P. In vitro comparative inhibition profiles of major human drug metabolising cytochrome P450 isozymes (CYP2C9, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4) by HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s002280050094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrighton SA, Ring BJ. Inhibition of human CYP3A catalyzed 1′-hydroxy midazolam formation by ketoconazole, nifedipine, erythromycin, cimetidine, and nizatidine. Pharm Res. 1994;11:921–924. doi: 10.1023/a:1018906614320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Schmider J, et al. Midazolam hydroxylation by human liver microsomes in vitro: Inhibition by fluoxetine, norfluoxetine, and by azole antifungal agents. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:783–791. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olkkola KT, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. Midazolam should be avoided in patients receiving the systemic antimycotics ketoconazole or itraconazole. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:481–485. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prueksaritanont T, Gorham LM, Hochman J, Tran L, Vyas KP. Comparative studies of drug metabolizing enzymes in dog, monkey and human small intestines and in Caco-2 cells. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996;24:634–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newton DJ, Wang RW, Lu AHY. Cytochrome P450 inhibitors: Evaluation of specificities in the in vitro metabolism of therapeutic agents by human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:154–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silverman RB. Mechanism-Based Enzyme Inactivation: Chemistry and Enzymology. Vol. 1. Boca Raton: FL. CRC Press; 1988. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parke-Davis . Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Co; 1998. Lipitor (Atorvastatin calcium): Physicians’ Desk Reference; pp. 2186–2189. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dain JG, Fu E, Gorski J, Nicoletti J, Scallen TJ. Biotransformation of fluvastatin sodium in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiba M, Nishime JA, Lin JH. Potent and selective inactivation of human liver microsomal cytochrome P-450 isoforms by L-754,394, an investigational human immune deficiency virus protease inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1527–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiltshire HR, Sutton BG, Heeps M, et al. Metabolism of the calcium antagonist, mibefradil (POSICOR™, Ro 40–5967). Part III. Comparative pharmacokinetics of mibefradil and its major metabolites in rats, marmoset, cynomolgus monkey and man. Xenobiotica. 1997;27:557–571. doi: 10.1080/004982597240343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray M, Reidy GF. Selectivity in the inhibition of mammalian cytochromes P-450 by chemical agents. Pharmacol Rev. 1990;42:85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amsden GW. Macrolides versus azalides: a drug interaction update. Ann Pharmacother. 1995;29:906–917. doi: 10.1177/106002809502900913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ochmann K, Mueck W, Unger S, Kuhlmann J. Influence of erythromycin pre- and co-treatment on the single-dose pharmacokinetics of cerivastatin. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52(Suppl):A139. doi: 10.1007/s002280050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]