Abstract

Aims

To quantify and compare the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias associated with the use of five nonsedating antihistamines: acrivastine, astemizole, cetirizine, loratadine and terfenadine. The effects of age, sex, dose, duration of treatment, and the interaction with P450 inhibitor drugs were also examined.

Methods

We carried out a cohort study with a nested case-control analysis using the UK-based General Practice Research Database (GPRD). The study cohort included persons aged less than 80 years old who received their first prescription for any of the five study drugs between January 1, 1992 and September 30, 1996. We estimated relative risks and 95% confidence intervals of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias with current use of antihistamines as compared with non use.

Results

The study cohort included 197 425 persons who received 513 012 prescriptions. Over the study period 18 valid cases of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias were detected. Nine occurred during the current use of any antihistamine, resulting in a crude incidence of 1.9 per 10 000 person-years (95%CI: 1.0–3.6) and a relative risk of 4.2 (95%CI: 1.5–11.8) as compared with non use. Astemizole presented the highest relative risk (RR = 19.0; 95%CI: 4.8–76.0) of all study drugs, while terfenadine (RR = 2.1; 95%CI:0.5–8.5) was in the range of other nonsedating antihistamines. Older age was associated with a greater risk of ventricular arrhythmias (RR = 7.4; 95%CI: 2.6–21.4) and seemed to increase the effect of antihistamines (RR = 6.4; 95%CI: 1.7–24.8). The proportions of high dose terfenadine and the concomitant use with P450 inhibitors among current users of terfenadine were 2.7% and 3.4%, respectively over the study period with no single case of ventricular arrhythmias occurring in the presence of these two risk factors.

Conclusions

The use of nonsedating antihistamines increases the risk of ventricular arrhythmias by a factor of four in the general population. Yet, the absolute effect is quite low requiring 57 000 prescriptions, or 5300 person-years of use for one case to occur. The risk associated with terfenadine was no different from that with other nonsedating antihistamines.

Keywords: ventricular arrhythmias, antihistamines

Introduction

In the early nineties terfenadine was singled out by case reports and electrophysiological studies as a proarrhythmic agent [1–4]. Terfenadine blocks cardiac potassium channels and prolongs the action potential, resulting in a longer QT interval in the electrocardiogram [4]. This mechanism is thought to be the basis for serious ventricular arrhythmias, in particular torsades de pointes [5]. When administered at therapeutic doses terfenadine is hardly detected in plasma due to an extensive first-pass degradation in liver through the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP3A4 [6]. The therapeutic antihistaminic activity is mediated by fexofenadine, its carboxylated metabolite [7]. Fexofenadine lacks the cardiac effects of its parent drug [4], and so the risk of QT prolongation and subsequent ventricular arrhythmias at therapeutic doses is mostly apparent when this metabolic pathway is inhibited. [8]. A warning about this risk was added to the labelling of terfenadine as early as 1990 [9], and since 1992 this was extended to the concomitant use of cytochrome P450 inhibitors as well as the use of terfenadine in individuals with ‘significant hepatic dysfunction’ and in those with congenital long QT interval [10]. A warning not to exceed the recommended dose of 60 mg twice daily was also included. Two epidemiological studies carried out in the US identified an excess risk of ventricular arrhythmias when terfenadine was used with P450 inhibitors but failed to show an increase in the risk of the population at large as compared to traditional antihistamines and other drugs [11, 12], suggesting that the use of terfenadine under the authorized conditions was safe for the general population.

In July, 1996 fexofenadine was launched in the US. Six months later, on 13 January, 1997 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced their intention to suspend the authorizaton of all products containing terfenadine [13]. The FDA explained that this action was not due to a change in the benefit-risk assessment of terfenadine itself, but rather to the availability of a drug with a more favourable benefit-risk balance. On 14 February 1997, France decided to suspend the marketing authorization for terfenadine containing products (action then followed by Luxembourg, Greece and Italy), and referred the issue to the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products (CPMP) of the European Union (EU) for an opinion on the benefit-risk balance of terfenadine as compared with other nonsedating antihistamines available in the EU [14]. By that time fexofenadine had just been marketed in the UK, and was engaged in a mutual recognition procedure for authorization in most EU countries.

When this regulatory problem arose, no epidemiological data were available comparing the risk of ventricular arrhythmias following terfenadine with other nonsedating antihistamines. A report from the WHO Collaborating Center for International Drug Monitoring comparing the number of reports of cardiac arrhythmias of five nonsedating antihistamines adjusted by sales data, suggested that although terfenadine appeared more frequently implicated, other antihistamines ‘may have similar problems’ [15]. We decided, then, to undertake the present study, independently, with the goal of providing additional epidemiological data into the decision procedures already in progress in the EU. The main objective was to quantify and compare the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias associated with the use of five non sedating antihistamines: acrivastine, astemizole, cetirizine, loratadine and terfenadine, using the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) in the UK, which had been shown in previous studies as a valid and efficient primary source of information for drug safety issues [16].

Methods

About 2000 general practitioners (GPs) in England and Wales use computers in their offices for the purpose of recording medical patient information in a standard manner. They have agreed to provide the information anonymously to the ONS (Office of National Statistics) and to allow the information to be used for research projects. The information recorded includes demographics, all medical diagnoses, referrals to consultant and hospital, and all prescriptions issued. Prescriptions are automatically produced from the computer and recorded on the patients’ computerized medical records. A previous study utilizing this computerized data source has documented that over 90% of all referrals are entered on the GPs’ computers with a code that reflects the consultant diagnosis [17]. An additional requirement of this data resource is that the indication for any new course of treatment be entered in the computer. In addition, the GP may record laboratory results and other medical data in a free text comment field. A modification of the OXMIS classification is used to code specific diagnoses, and a drug dictionary based on the Prescription Pricing Authority drug dictionary is used to record drugs.

Study population

The source population was derived from 383 practices including approximately three million individuals registered with general practitioners in these practices. The study period started on 1st January 1992 and ended on 30th September 1996. Persons aged less than 80 years old were entered into the study cohort after their first prescription for acrivastine, astemizole, cetirizine, loratadine, and terfenadine (start date) during the study period. Subjects who had a computer mention of cardiac ventricular arrhythmias, or cancer prior to the date of entering the study period were excluded. Patients were followed from start date until the earliest occurrence of one of the following study endpoints (stop date): a code suggesting cardiac ventricular arrhythmias, cancer, death, end of study period, age of 80 years, or 1 year after last prescribed study drug.

Case ascertainment and validation

We identified among the study population 151 subjects who had a first-time recorded code suggesting cardiac ventricular arrhythmias. We reviewed their computerized patient profile to eliminate those with a presumed diagnosis recorded on computer which was not subsequently confirmed and patients who were not referred to a consultant or a hospital (n = 60). All patient personal identifiers and drug use information were suppressed before review to maintain confidentiality and avoid information bias, respectively. We requested from the general practitioners clinical records for all remaining 91 potential cases and received information on 86 patients (95%). Persons were defined as cases of cardiac ventricular arrhythmias when they presented clinical symptoms that resulted in a referral to a specialist or hospitalization, together with objective evidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and absence of a recent acute angina or myocardial infarction. After review of all available information by one of us (LAGR) and a consultant in cardiology, 68 were not considered cases of ventricular arrhythmias. The reasons for exclusion were: diagnosis not confirmed (19), supraventricular arrhythmias (14), not referred (8), past history of ventricular arrhythmias (12), MI/angina (6), right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia (2), computer entry error (2), finding in routine check-up (2), arrhythmias developed in-hospital (2) and sarcoidosis (1). The remaining 18 patients were considered cases of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias (no alternative cause for ventricular arrthythmias was documented in the clinical record). The date of first diagnosis of clinical symptoms was considered the index day. There were no fatal cases.

Exposure definition

Three levels of exposure were defined for each antihistaminic drug: ‘current use’ (period of time from the day a prescription was issued until 10 days after the end of drug supply), ‘past use’ (period of 90 days after the end of the ‘current use’ time-window) and ‘non-use’ (all remaining person-time). We used the same window definitions for exposure to P450 inhibitors. Any overlap of drug supplies for P450 inhibitors and antihistamines was considered concomitant treatment.

Analysis

Crude incidence rates of cardiac ventricular arrhythmias in each exposure category were computed. A nested case-control analysis was undertaken in order to examine more efficiently the effect of age, sex, dose and duration relationships, and the interaction with hepatic disease and concomitant exposure to P450 inhibitor drugs (clarythromycin, erythromycin, fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole, miconazole, clotrimazol, and fluvoxamine). For the purpose of the analysis, it was considered ‘current concomitant exposure’ when the end of drug supply for both P450 inhibitors and antihistamines was less than 10 days before the index date. Controls were randomly sampled from the pool of person-time of the study cohort [18]. A date included in the study period was generated at random for all members of the study cohort. If the random date of a study member was included in his or her eligible person-time, we used his or her random date as the index date and marked that person as an eligible control. The same exclusion criteria applied to cases were used with the control series. Finally, 2000 controls were selected randomly from the list of eligible controls. We computed adjusted estimates of relative risk and 95% confidence intervals of ventricular arrhythmias associated with current use of individual antihistaminic drugs compared to non use with unconditional logistic regression.

Results

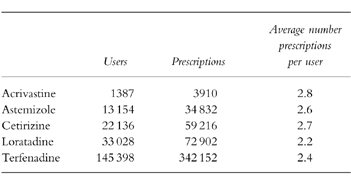

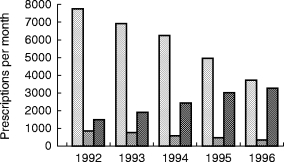

The final study cohort included 197 425 persons who received 513 012 prescriptions (2.6 per user). The corresponding number of users and prescriptions for each individual antihistaminic drug are shown in Table 1. The use of terfenadine decreased in the source population by 52% over the study period, but it was still the most prescribed nonsedating antihistamine in 1996 (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Study cohort by users of individual antihistamines and prescriptions.

Figure 1.

Trend of the average number of prescriptions of antihistamines per month in the source population. ( terfenadine,

terfenadine, astemizole,

astemizole,  all others).

all others).

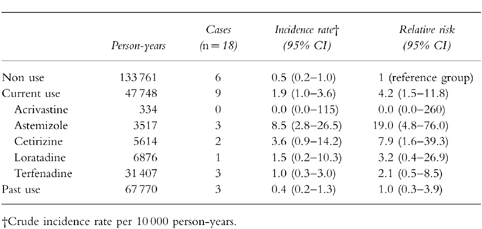

Nine cases occurred during current use of any antihistamine, resulting in a crude incidence of 1.9 per 10 000 person-years (95%CI: 1.0–3.6), a rate 4.2 (95%CI: 1.5–11.8) times higher than the one observed during the non-use period (Table 2). One case of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias occurred out of 57 000 prescriptions of nonsedating antihistaminic drugs. By individual drugs only astemizole (RR = 19.0; 95%CI: 4.8–76.0) and cetirizine (RR = 7.9; 95%CI: 1.6–39.3) showed confidence intervals that excluded the null value. The risk associated with terfenadine (RR = 2.1, 95%CI: 0.5–8.5) was in the range of nonsedating antihistamines as a group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence rate and relative risk of ventricular arrhytmias associated with current and past use of antihistamine drugs (cohort analysis).

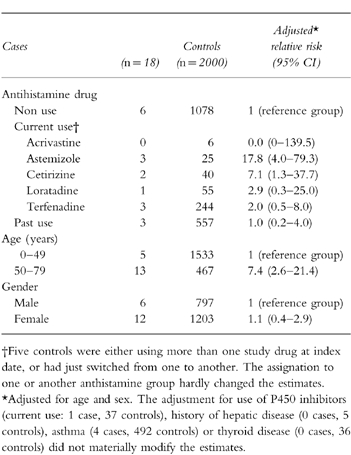

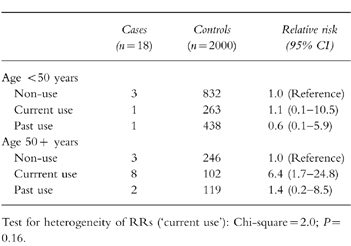

The nested case-control analysis provided adjusted estimates of RR similar to the crude estimates from the cohort analysis (Table 3). The risk of astemizole was significantly greater than that for all other nonsedating anthistamines considered altogether (RR = 6.4; 95%CI: 1.4–28.6). Age appeared as an independent risk factor for ventricular arrhythmias (RR = 7.4; 95%CI: 2.6–21.4). When results were stratified by age group, the risk of ventricular arrhythmias was only observed in the older population stratum (RR = 6.4, 95%CI: 1.7–24.8), which suggests that age may be acting as an effect modifier (Table 4). However, the test for heterogeneity of RRs across the strata did not reach significance (P = 0.16).

Table 3.

Relative risk of ventricular arrhytmias associated with use of antihistamine drugs and other variables (case-control analysis).

Table 4.

Effect of age on the risk ventricular arrhythmias associated with antihistamines.

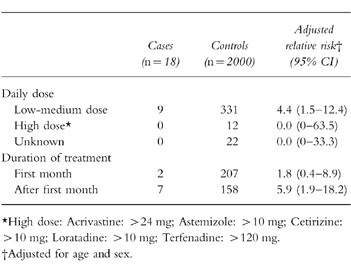

The proportion of terfenadine prescriptions issued with a daily dose greater than 120 mg was 2.7% during the whole period. A declining trend from 4.5% in 1992 to 1.6% in 1996 was observed. Among astemizole prescriptions, 4.2% were issued at doses higher than 10 mg, and they also exhibited a declining trend from 5.0% to 3.1%. All nine cases occurring during current use of antihistamines were on recommended daily doses or below. Seven cases occurred after the first month of treatment (RR = 5.9; 95%CI: 1.9–18.2) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Dose and duration relationships of nonsedating antihistamines with the risk of ventricular arrhythmias.

Over the study period, 11 589 prescriptions of terfenadine were issued concomitantly with P450 inhibitor drugs (3.4%), and only 10 were concomitant with ketoconazole (3 per 100 000 prescriptions of terfenadine). With astemizole, the figures were 3.3% and 9 per 100 000, respectively. The remainder nonsedating antihistamines presented slightly higher proportions: 4.5% and 12 per 100 000. No single case of ventricular arrhythmias was detected during the periods of concomitant exposure of terfenadine or astemizole with P450 inhibitors.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that nonsedating antihistaminic drugs increase the risk of cardiac ventricular arrhythmias by a factor of four in the general population. Yet, the absolute effect is quite low, requiring about 57 000 prescriptions, or 5300 person-years of current use, for one case to occur. Under the actual conditions of use in our study population, terfenadine did not show a higher risk of ventricular arrhythmias than other nonsedating antihistamines as a group.

Our results with terfenadine are consistent with those from other population-based studies reported previously. Pratt et al. [11] using Medicaid databases in the US compared the incidence of life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias and related events (cardiac arrest and sudden death) among the recipients of terfenadine prescriptions with respect to those receiving over-the-counter antihistamines, clemastine and ibuprofen. After adjusting for potential confounders, they found similar risks for terfenadine compared with reference drugs. However, among those who used terfenadine and ketoconazole concomitantly there was a RR of 26 (95%CI: 7–16) as compared with terfenadine alone. No excess risk was observed with the concomitant use of terfenadine and erythromycin, and only a marginally significant small increase in presence of hepatic disease. One year later, Hanrahan et al. [12] using another automated database in the US (Harvard Community Health Plan) did not find either an excess risk of clinical (syncope and sudden death) or arrhythmic events (simple or complex ectopy) associated with terfenadine as compared to other prescription antihistamines (OR = 0.9; 95%CI: 0.5–1.4). Nor did they find an excess risk of QTc prolongation, except when erythromycin was administered concomitantly (two-fold increase). Although these two studies and the present one have important differences in case definition and study design, all support the hypothesis that in the general population there is no excess risk associated with terfenadine, as compared to other antihistamines, either sedating or non-sedating.

The study of cardiac arrhythmic risk associated with astemizole has attracted less attention and the available data are more limited than in the case of terfenadine, even though the case reports relating torsades de pointes and sudden death with astemizole use preceded by several years those implicating terfenadine [19–21]. In a number of experimental models, astemizole has been shown to block potassium currents and to prolong the QT interval at clinically relevant concentrations [5]. Like terfenadine, astemizole is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CPY3A4, but in contrast, its major metabolites retain the cardiac effect of the parent drug [5]. Another relevant pharmacokinetic feature is that astemizole metabolites are cleared very slowly from plasma with apparent half-lives of 18 to 20 days [22], thereby requiring several weeks to reach steady state on continuous treatment or to dissapear from blood after its discontinuation. P450 inhibitors have also been reported to interfere with the metabolism of astemizole, increasing its serum levels and the risk of arrhythmias as a result [22]. In our study, the risk of ventricular arrhythmias associated with astemizole use was higher than that associated with other nonsedating antihistamines. Taken together, these data suggest that prescribers should be more cautious when using astemizole than when using other nonsedating antihistamines, as far as the risk of ventricular arrhythmias is concerned. Staffa et al. [23] using one of the Medicaid databases did not find an increased risk of serious cardiac events among astemizole users compared with users of sedating antihistamines. This result could lend support to the hypothesis that sedating antihistamines, most of them OTC drugs, may not be as safe as generally assumed [5, 11].

Both loratadine and cetirizine have been thought to be free of arrhythmogenic properties because they appear not to increase the QT interval, even at doses far exceeding those recommended [5]. In apparent contradiction, spontaneous reporting schemes have received reports implicating both drugs in cases of serious ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death [15]. These reports have been considered until now as false positives. Recently, however, it has been reported that loratadine blocks a Kv1.5 type potassium channel closed from human atrial myocytes [24, 25]. Although the concentrations at which this effect becomes apparent seem to be beyond the therapeutic range of plasma concentrations of loratadine [25], these results could give some biological support to the reported cases and suggest that it may not be wise to single out loratadine as a drug completely devoid of ventricular arrhythmias risk. Until more information is available, our results support the idea that nonsedating antihistamines as a group increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias and that all may share this problem to some extent.

We did not identify any of the risks factors commonly implicated in terfenadine-associated arrhythmias (high doses, interaction with P450 inhibitors, and hepatic disease), most likely due to the low prevalence of such factors in the study population. This should be kept in mind when the results are interpreted because they may have limited generalizability to other populations where conditions of use are different. In particular there was low joint use with oral ketoconazole, the most commonly implicated drug in serious clinical interactions with terfenadine [4]. In another study, Thompson & Oster [26] reported a 0.36% rate of overlapping use of terfenadine and ketoconazole among the members of a large health insurance company in New England, USA, in 1994, a rate 100 times higher than that in our study, while the proportion of overlapping use with macrolides antibiotics, mainly erythromycin, was rather similar (2–3%) [26] in both studies. Our data indicate that age is a strong risk factor for arrhythmias, and suggest that it could also be an effect modifier of antihistamine-induced ventricular arrhythmias. In subjects aged 50 years or older the use of antihistamines was associated with a six-fold increase in risk, whereas no effect was seen in younger people. Although this interaction makes biological sense, as older people are more likely to have subclinical heart lesions that may make them more susceptible to the arrhythmogenic effect of antihistamines, a cautious interpretation of this subgroup analysis is required due to the small number of cases in each stratum.

In addition to the limited precision of our estimates, other methodological limitations should be taken into account. Selection bias may have occurred if GPs could identify those patients who will later develop ventricular arrhythmias and selectively avoid prescribing terfenadine to them. In our view, this is very unlikely to have happened unless the criteria used for such a selection were not explicitly indicated in the clinical records. Referral bias may also be a possibility, if GPs referred patients with minor arrhythmias to the specialist or hospital when they realized that the patient was taking terfenadine or astemizole. This bias would have tended to overestimate the risks of both drugs. The review of clinical records for all cases and the requirement for objective evidence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias should have minimized the magnitude of this bias. Our study has a potential for exposure misclassification since terfenadine and astemizole for the whole study period, and loratadine and cetirizine since 1993, were also available in pharmacies as non-prescription drugs for a maximum 10-days supply, and patients may have used them during the non-use periods. This misclassification would have tended to artificially increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias during the non-use periods, which in turn would have led to underestimate the effect of prescription non-sedating antihistamines. Finally, we controlled for potential confounders by restricting the study population to those without past history of cardiac ventricular arrhythmias, by using strict validation criteria for cases and by adjusting for some potential predictors in the case-control analysis. Nonetheless, residual confounding by unknown or unmeasured factors can never be ruled out completely.

Preliminary results of this study were shared with the EU regulatory authorities during the process of risk assessment of terfenadine. On November 19, 1997 the CPMP recommended the maintenance of the Marketing Authorizations of terfenadine 60 mg and 30 mg tablets and 6 mg ml−1 oral suspension formulation, and the withdrawal of the 120 mg strength and the fixed-dose combination with pseudoephedrine [14]. A new wording of the Summary of Product Characteristics stressing the contraindications of the drug and the warnings for use was set out [14], and those countries with a non-prescription status for terfenadine took the necessary measures to change it back to prescription-only-medicine [27].

Acknowledgments

We thank the participating general practitioners for their invaluable cooperation and Dr Manuel de los Reyes (Instituto de Cardiología de Madrid) for reviewing the medical records.

During the preparation of the present work Francisco J. de Abajo was at Harvard School of Public Health, where he was supported by a grant from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (BAE 97/5582 and 98/5006) and held a scholarship from Harvard Program in Pharmacoepidemiology.

References

- 1.Monahan BP, Ferguson CL, Killeavy ES, et al. Torsades de pointes occurring in association with terfenadine use. JAMA. 1990;264:2788–2790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacConnell TJ, Stanners AJ. Torsades de pointes complicating treatment with terfenadine. Br Med J. 1991;302:1469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6790.1469-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mathews DR, McNutt B, Okerholm R, et al. Torsades de pointes occurring in association with terfenadine use. JAMA. 1991;266:2375–2376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woosley RL, Chen Y, Freiman JP, Gillis RA. Mechanism of the cardiotoxic actions of terfenadine. JAMA. 1993;269:1532–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woosley RL. Cardiac actions of antihistamines. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:233–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.001313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yun C, Okerholm RA, Guengerich FP. Oxidation of the antihistaminic drug terfenadine in human liver microsomes. Role of cytochrome P45034A in N-dealkylation and C-hydroxylation. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorkin EM, Heel RC. Terfenadine: a review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1985;29:34–56. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198529010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Estelle F, Simons R. H1-Receptor Antagonists-Comparative tolerability and safety. Drug Safety. 1994;10:350–380. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199410050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mastey V. Torsades de pointes in patients receiving terfenadine or astemizol. Drug and Devices Information Line. Harvard School of Public Health. http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/organizations /DDIL/ddil.html.

- 10.Nightingale SL. Warnings issued on nonsedating antihistamines terfenadine and astemizole. JAMA. 1992;268:705. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pratt CM, Hertz RP, Ellis BE, Crowell SP, Louv W, Moye L. Risk of developing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmia associated with terfenadine in comparison with over-the-counter antihistamines, ibuprofen and clemastine. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:346–352. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanranhan JP, Choo PW, Carlson W, Greineder D, Faich G, Platt R. Terfenadine-associated ventricular arrythmias and QTc interval prolongation. A retrospective cohort comparison with other antihistamines among members of a health maintenance organization. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:201–209. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00039-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FDA Talk paper. FDA proposes to withdraw Seldane approval. 1997 Jan 13 http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/ANS00780.html.

- 14.The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. Final Opinion of the Committe for Proprietary Medicinal Products pursuant to article 12 of Council Directive 75/319/EEC as amended for Terfenadine containing products. London: 1997. 25 February. CPMP/255/98-EN. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linquist M, Edwards IR. Risks of non-sedating antihistamines. Lancet. 1997;349:1322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)26018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.García Rodríguez LA, Pérez Gutthann S. Use of the UK General Practice Research Database for pharmacoepidemiology. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45:419–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jick H, Jick SS, Derby L. Validation of information recorded on general practitioner based computerised data resource in the United Kingdom. Br Med J. 1991;302:766–768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6779.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker AM. Observation and Inference. An introduction to the methods of epidemiology. Newton Lower Falls: Epidemiology Resources; 1991. pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craft TM. Torsades de pointes after astemizole overdose. Br Med J. 1986;292:660–668. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6521.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snook J, Boothman-Burrell D, Watkins J, Colin-Jones D. Torsades de pointes ventricular tachychardia associated with astemizole overdose. Br J Clin Pract. 1988;42:257–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simons FE, Kesselman MS, Giddins NG, Pelech AN, Simons KJ. Astemizole-induced torsades de pointes. Lancet. 1988;ii:624. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desager JP, Horsmans Y. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationships of H1-antihistamines. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;28:419–432. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199528050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staffa JA, Jones JK, Gable CB, Verspeelt JP, Amery WK. Risk of selected serious cardiac events among new users of antihistamines. Clin Ther. 1995;17:1062–1077. doi: 10.1016/0149-2918(95)80085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacerda AE, Roy ML, Lewis EW, Rampe D. Interactions of the nonsedating anthistamine loratadine with a Kv1.5-type potassium channel cloned from human heart. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:314–322. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.2.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delpón E, Valenzuela C, Pilar Gay, Franqueza L, Snyders DJ, Tamargo J. Block of human cardiac Kv1.5 channels by loratadine: voltage-, time-, and use-dependent block at concentrations above therapeutic levels. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:341–350. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson D, Oster G. Use of terfenadine and contraindicated drugs. JAMA. 1996;275:1339–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rankin AC. Non-sedating antihistamines and cardiac arrhythmia. Lancet. 1997;350:1115–1116. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63783-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]