Abstract

Background and purpose:

Low efficacy partial agonists at the D2 dopamine receptor may be useful for treating schizophrenia. In this report we describe a method for assessing the efficacy of these compounds based on stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding.

Experimental approach:

Agonist efficacy was assessed from [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes of CHO cells expressing D2 dopamine receptors in buffers with and without Na+. Effects of Na+ on receptor/G protein coupling were assessed using agonist/[3H]spiperone competition binding assays.

Key results:

When [35S]GTPγS binding assays were performed in buffers containing Na+, some agonists (aripiprazole, AJ-76, UH-232) exhibited very low efficacy whereas other agonists exhibited measurable efficacy. When Na+ was substituted by N-methyl D-glucamine, the efficacy of all agonists increased (relative to that of dopamine) but particularly for aripiprazole, aplindore, AJ-76, (−)-3-PPP and UH-232. In ligand binding assays, substitution of Na+ by N-methyl D-glucamine increased receptor/G protein coupling for some agonists -. aplindore, dopamine and (−)-3-PPP – but for aripiprazole, AJ-76 and UH-232 there was little effect on receptor/G protein coupling.

Conclusions and implications:

Substitution of Na+ by NMDG increases sensitivity in [35S]GTPγS binding assays so that very low efficacy agonists were detected clearly. For some agonists the effect seems to be mediated via enhanced receptor/G protein coupling whereas for others the effect is mediated at another point in the G protein activation cycle. AJ-76, aripiprazole and UH-232 seem particularly sensitive to this change in assay conditions. This work provides a new method to discover these very low efficacy agonists.

Keywords: D2 dopamine receptor, [35S]GTPγS binding, ligand binding, signalling efficacy, sodium ions

Introduction

The G-protein-coupled receptors constitute about 50% of the targets for current drugs. Hence, there is much interest in understanding their mechanisms of action. Some drugs are antagonists/inverse agonists and act by reducing the activity of the signalling system. Examples are the anti-ulcer drug, cimetidine, which acts at the histamine H2 receptor suppressing constitutive activity leading to receptor upregulation (Smit et al., 1996). Agonist drugs are also used and examples here are the anti-asthma drug, salbutamol, which acts at the β2 adrenergic receptor and the anti-anxiety drug, buspirone, which acts at the 5-HT1A serotonin receptor. The use of drugs that are agonists can pose practical problems in that desensitization and down-regulation of receptors may occur. Also, there may be potential problems with overdose with an agonist drug. For these reasons, there has been an interest in the development of low efficacy partial agonist drugs which may have reduced problems with regard to loss of receptor response and have a built-in limit to their effects.

The D2 dopamine receptor is of interest in this regard. For example, there is current interest in the use of agonists to treat schizophrenia. Antipsychotic drugs have typically been antagonists or inverse agonists at the D2 receptor. Recently, however, aripiprazole was introduced and shown to be effective as a treatment for this disorder (McGavin and Goa, 2002; Grady et al., 2003; Potkin et al., 2003). Aripiprazole has been reported to be a low efficacy partial agonist at the D2 receptor (Burris et al., 2002). The principle of using low efficacy partial agonists to treat schizophrenia has been discussed independently and these compounds have been described as ‘dopamine stabilizers' (Carlsson et al., 2001) as they should counteract both hyperactivity and hypoactivity in dopamine systems.

Because of this interest in the development of low efficacy partial agonist drugs, it has become important to have reliable systems to assess partial agonist activity. For compounds with very low relative efficacy, this can be difficult as in some of the assay systems used typically, for example, stimulation of guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate ([35S]GTPγS) binding, these compounds will appear silent. When other assay systems are employed, these compounds may appear to switch between being partial agonists and antagonists.

The relative efficacy of partial agonists has been reported to be increased by changing the guanosine diphosphate (GDP) concentration or the sodium ion concentration in [35S]GTPγS binding assays (Costa et al., 1992; Selley et al., 1997, 2000; Gazi et al., 2003; Roberts et al., 2004a). In the present study, therefore, we have modified the [35S]GTPγS binding assay for the D2 dopamine receptor by removing sodium ions and maintaining ionic strength with the sodium ion substitute N-methyl D-glucamine (NMDG) (Nunnari et al., 1987). We report experiments where we have increased the sensitivity of the [35S]GTPγS binding assay so that it can be used to detect these very low efficacy partial agonists and to discriminate between them. We have also probed the mechanism behind this new system.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing human D2short dopamine receptors (Wilson et al., 2001) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 5% foetal bovine serum and 400 μg ml−1 active geneticin (to maintain selection pressure). Cells were grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Membrane preparation

Membranes were prepared from CHO cells expressing D2short dopamine receptors as described previously (Castro and Strange, 1993). Briefly, confluent 175 cm2 flasks of cells were washed once with 5 ml 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethyl-sulphonic acid (HEPES) buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1 mM ethyleneglycol tetraacetate (EGTA), 1 mM ethylenediamenetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 10 mM MgCl2; pH 7.4). Cells were then removed from the surface of the flasks using 5 ml HEPES buffer and glass balls (2 mm diameter) and were then homogenized using an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (two 5 s treatments). The homogenate was centrifuged at 250 g (10 min, 4°C) after which the supernatant was centrifuged at 48 000 g (60 min; 4°C). The resulting pellet was resuspended in HEPES buffer at a concentration of 3–5 mg protein ml−1 (determined by the method of Lowry et al. (1951)) and stored in aliquots at −70°C until use.

Radioligand binding assays

Cell membranes (25 μg) were incubated in triplicate with [3H]spiperone (∼0.25 nM) and competing drugs in HEPES buffer (20 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl or 100 mM NMDG (to maintain ionic strength in the absence of sodium ions (Nunnari et al., 1987)); pH 7.4 (using HCl) containing 0.1 mM dithiothreitol) in a final volume of 1 ml for 3 h at 25°C. The assay was terminated by rapid filtration (through Whatman GF/C filters) using a Brandel cell harvester followed by four washes with 4 ml ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (0.14 M NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.5 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM Na2HPO4; pH 7.4) to remove unbound radioactivity. Filters were soaked in 2 ml of scintillation fluid for at least 6 h and bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Nonspecific binding of [3H]spiperone was determined in the presence of 3 μM (+)-butaclamol.

[35S]GTPγS binding assays

Cell membranes (25 μg) were incubated in triplicate with ligands for 30 min at 30°C in 0.9 ml of HEPES buffer containing 1 μM GDP and 100 mM NaCl, NMDG, LiCl or KCl where indicated. The assay was initiated by addition of 100 μl of diluted [35S]GTPγS to give a final concentration of 50–100 pM. The assay was incubated for a further 30 min and terminated by rapid filtration as above. In some kinetic assays, termination occurred at different times after the addition of the [35S]GTPγS.

Data analysis

Results in the text are shown as means±s.e.m., along with the number of experiments. Radioligand binding data were analysed using Prism (GraphPad) and were assumed to conform to a one-binding site model unless a statistically better fit could be obtained using a two-binding site model (P<0.05, F-test). In competition experiments that were fitted best by a one-binding site model, a single inhibition constant (IC50) value was obtained, whereas in competition experiments that were fitted best by a two-binding site model, two IC50 values (for the higher and lower affinity sites) and the % higher affinity sites were obtained. The inhibition constants (Ki from the single IC50, Kh, Kl from the IC50 values for the higher and lower affinity sites) were calculated from IC50 values, derived from competition binding analyses, using the Cheng–Prusoff equation (Cheng and Prusoff, 1973), as described by Roberts et al. (2004b). This corrects for the concentration of the radioligand ([3H]spiperone) and its dissociation constant at the relevant binding site. The dissociation constant for [3H]spiperone was unaffected by the different conditions used. pKd values of 10.63±0.04 (+Na+) and 10.52±0.03 (+NMDG) (mean±s.e.m., three experiments, P>0.05) were found in agreement with Armstrong and Strange (2001). Also previous work has shown that GTP does not affect the pKd for [3H]spiperone (Payne et al., 2002). Data from [35S]GTPγS binding experiments were fitted to a sigmoidal concentration/response curve with a Hill coefficient of one which provided the best fit to the data in all cases (P<0.05). Time course data were fitted well by mono-exponential equations from which the apparent first-order rate constant (k, min−1) and maximal binding (Bmax, fmol mg−1) values could be extracted. The initial rate of [35S]GTPγS binding was calculated as k.Bmax in fmol mg−1 min−1.

Statistical significance of differences between two data sets (e.g. two sets of pKi values) was determined using one way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni post-test with significance determined as P<0.05.

Materials

[35S]GTPγS (∼37 TBq mmol−1) and [3H]spiperone (∼600 GBqmmol−1) were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Buckinghamshire, UK). Optiphase HiSafe-3 scintillation fluid was purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences (Cambridge, UK). Dopamine, bromocriptine, (1S,2R)-cis-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(N-propylamino)tetralin (AJ-76) and cis-(+)-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(di-N-propylamino)tetralin (UH-232) were purchased from TOCRIS (Bristol, UK). NMDG, p-tyramine and S-(−)-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-N-propylpiperidine hydrochloride ((−)-3-PPP) were purchased from Sigma (Dorset, UK). Aripiprazole and aplindore were generous gifts from GSK and Wyeth, respectively.

Results

Agonist stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding

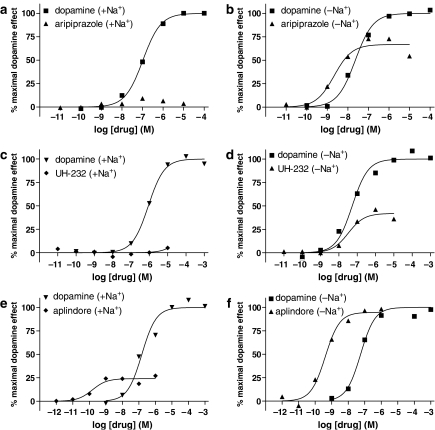

The ability of a range of concentrations of both dopamine and other agonists to stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes from CHO cells is illustrated in Figure 1. These membranes were prepared from CHO cells and expressed the D2 receptor at 1–2 pmol mg−1 protein (CHO–D2 cells; Wilson et al., 2001). The experiments were performed under two conditions: (i) GDP (1 μM) and sodium ions (100 mM), these being standard conditions for these experiments (Gardner and Strange, 1998), (ii) with GDP but without sodium ions, the sodium ions being replaced by NMDG as a cation substitute to maintain ionic strength.

Figure 1.

Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by agonists in membranes of CHO-D2 cells. Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by the agonists indicated was determined as described in the Materials and methods under different conditions. Responses to dopamine were compared with those to aripiprazole (a, b), UH-232 (c, d) and aplindore (e, f). Buffers contained sodium ions (100 mM) (a, c, e) or the sodium ions were substituted by NMDG (100 mM) (b, d, f). GDP was present throughout at 1 μM. The data are from representative experiments that have been replicated three times with similar results. Derived parameters are given in Table 1.

Basal levels of [35S]GTPγS binding were increased by substitution of Na+ by NMDG, by 42.4±4.6% ((n=36; see also Figure 2). Dopamine was able to stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding over basal levels under both conditions. The stimulation over basal [35S]GTPγS binding was highest (91.7±4.4%; n=36) when sodium ions were present. Removal of sodium ions and substitution of NMDG, reduced the maximal stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding over basal by dopamine (stimulation over basal 35.5±2.3%; n=36). The net increase in [35S]GTPγS binding in fmol mg−1 protein owing to maximally stimulating concentrations of dopamine was reduced to 52.2±2.4% (n=36) upon substitution of Na+ by NMDG.

Figure 2.

Cation selectivity for enhancement of agonist efficacy. Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by the agonists indicated was determined as described in the Materials and methods under different conditions. In (a) stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by dopamine (10 μM) and UH-232 (1 μM) was determined in buffers containing Na+ and NMDG in different ratios. In (b), stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by dopamine (10 μM), aripiprazole (1 μM) and UH-232 (1 μM) was determined in buffers containing 100 mM Na+, NMDG, Li+, K+. The data are mean±s.e.m. of triplicate determinations from representative experiments that have been replicated twice with similar results.

In experiments with the other agonists, data were expressed as a percentage of the maximum dopamine stimulation under the respective condition (Figure 1). AJ-76 suppressed basal [35S]GTPγS binding in the presence of Na+, whereas when NMDG was substituted for Na+, relative efficacy compared to dopamine was ∼50% (Table 1). For UH-232 and aripiprazole, little or no agonist-stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding was observed in the presence of Na+, whereas when NMDG was substituted for Na+, relative efficacy was substantial. Some compounds ((−)3-PPP, aplindore) were able to stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding in the presence of sodium ions and the relative efficacy increased substantially when sodium ions were omitted from assays. For other compounds (bromocriptine, dihydrexidine, p-tyramine), there was stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding in the presence of sodium ions but the relative efficacy increased only moderately when sodium ions were omitted. Changes in relative efficacy were significant for all compounds with the exception of dihydrexidine and bromocriptine (Table 1). Representative data for aripiprazole, UH-232 and aplindore in comparison to dopamine are shown in Figure 1. The potencies of the agonists under the two conditions were generally not affected by the removal of sodium ions (Table 1), although for dopamine there was a significant increase in potency. There were differences in the percentage stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by agonists in different preparations of membranes from the CHO-D2 cells, although this did not influence the changes in relative efficacy described here.

Table 1.

Agonist stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding

| +Na+ |

+NMDG |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative efficacy (%) | pEC50 | Relative efficacy (%) | PEC50 | |

| AJ-76 | −10.6±2.6 | 7.02±0.90 | 41.3±3.4* | 6.67±0.13 |

| Aplindore | 16.9±2.3 | 9.57±0.21 | 90.0±5.7* | 9.47±0.08 |

| Aripiprazole | 5.5±1.9 | — | 51.3±7.8* | 8.90±0.15 |

| Bromocriptine | 64.9±0.7 | 9.49±0.27 | 73.0±1.1 | 9.43±0.26 |

| Dihydrexidine | 60.8±4.7 | 6.98±0.04 | 76.9±3.7 | 7.32±0.16 |

| Dopamine | 100 | 6.56±0.05 | 100 | 7.10±0.07* |

| (−)-3-PPP | 31.7±5.4 | 6.81±0.10 | 112.3±7.7* | 6.64±0.08 |

| p-tyramine | 48.0±2.2 | 4.56±0.19 | 75.4±9.7* | 5.16±0.16 |

| UH-232 | 0.2±2.7 | — | 64.7±7.9* | 7.34±0.14 |

Abbreviations: AJ-76, (1S,2R)-cis-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(N-propylamino)tetralin; EC50, median effective concentration; [35S]GTPγS, guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate; NMDG, N-methyl D-glucamine; (−)-3-PPP, S-(−)-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-N-propylpiperidine hydrochloride; UH-232, cis-(+)-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(di-N-propylamino)tetralin.

Agonist stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding was determined in buffers containing Na+ (100 mM) or NMDG (100 mM) as described in the Materials and methods section. For each agonist stimulation curve, the pEC50 and the maximal effect were determined. The maximal effect was expressed as a relative efficacy compared to dopamine determined in the same experiment. Data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. for three or more experiments.

P<0.05 relative to data in presence of Na+.

The specificity of the effect of substitution of Na+ by NMDG was assessed. First, experiments were conducted where Na+ was substituted by either K+ or Li+. These experiments showed that the effect of NMDG was specific in that little or no increase in relative efficacy for UH-232 or aripiprazole was seen with either Li+ or K+ (Figure 2). Next, the concentration dependence of the effect of substitution of Na+ by NMDG was assessed. Experiments were conducted with different ratios of Na+/NMDG and these showed that the increase in relative efficacy of UH-232 occurred only when the concentration of Na+ was reduced below 25 mM (Figure 2).

Time course of [35S]GTPγS binding

The time course of [35S]GTPγS binding stimulated by dopamine and aripiprazole in the presence of Na+ or NMDG was determined (Figure 3). The data showed that the rate constants for the binding reaction were similar for dopamine (Na+ versus NMDG) and for dopamine versus aripiprazole in the presence of NMDG, whereas the extent of binding was different. Initial rates of [35S]GTPγS binding in fmol min−1 mg−1 were calculated and are given in Figure 3. Similar data were obtained for UH-232 and were independent of whether there was a preincubation with agonist or not.

Figure 3.

Time course for agonist stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding. Stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding by dopamine (10 μM) and aripiprazole (1 μM) was determined as described in the Materials and methods after subtraction of basal values. The data are from a representative experiment that has been replicated four times with similar results. For the experiment shown, the initial rates of [35S]GTPγS binding in fmol min−1 mg−1 were dopamine/Na+ 4.83, dopamine/NMDG 4.39, aripiprazole/Na+ 0, aripiprazole/NMDG 1.81. From four experiments, the initial rate for aripiprazole/NMDG, expressed as a percentage of the dopamine rate under the same conditions was 42.1±6.3% (mean±s.e.m.). Rate constants (min−1) from four experiments were 0.028±0.001 (dopamine/Na+), 0.044±0.004 (dopamine/NMDG), 0.049±0.009 (aripiprazole/NMDG), these were not statistically different, P>0.05, ANOVA.

Ligand binding data

Ligand binding studies were conducted to try to understand the basis of the effects of sodium ions described above (Figure 4). One possibility is that sodium ions affect the binding of the agonists tested, leading to the observed changes in efficacy. Competition studies versus [3H]spiperone binding to CHO–D2 cell membranes expressing D2 receptors at 1–2 pmol mg−1 were, therefore, performed for the agonists in order to determine their affinities for the D2 receptor. Experiments were conducted in the presence of 100 mM Na+ or NMDG. It was also possible that sodium ions were affecting the ability of the agonists to stabilize the complex of receptor and G protein. For some compounds, therefore, the shapes of their binding curves were analysed and experiments were also conducted in the presence of GTP (100 μM) in order to disrupt receptor/G-protein coupling.

Figure 4.

Binding of agonists to D2 dopamine receptors in membranes of CHO-D2 cells. Binding of drugs was assayed in competition versus [3H]spiperone binding as described in the Materials and methods. Competition experiments are shown for dopamine (a), UH-232 (b) and aripiprazole (c) and experiments are shown in the presence and absence of GTP (100 μM) and in the presence of sodium ions (100 mM) and where sodium ions have been substituted by NMDG (100 mM). Competition curves are the best-fit curves to two-binding site models or one-binding site models (UH-232, aripiprazole, dopamine +Na++GTP).

For dopamine, competition curves in the absence of GTP were fitted best to a two-binding site model indicating receptor/G-protein coupling, whether sodium ions were present or not (Figure 4a; Table 2). When GTP was present, competition curves in the presence of sodium ions were fitted best by a one-binding site model and the affinity agreed with that seen in the absence of GTP for the lower affinity state, indicating disruption of receptor/G-protein coupling. In the absence of sodium ions, some competition curves fitted best to a one-binding site model in the presence of GTP, whereas some fitted best to a two-binding site model.

Table 2.

Binding of drugs to D2 dopamine receptors

| +Na+ | +Na++GTP | +NMDG | +NMDG +GTP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AJ-76 | 6.54±0.03 | 6.50±0.01 | 5.45±0.07* | 5.20±0.03* |

| Aplindore | pKh 10.22±0.29 | pKh 9.80±0.14 | ||

| pKl 9.08±0.16 | 9.03±0.09 | pKl 8.45±0.07* | 8.40±0.06* | |

| %Rh 15.22±7.8 | %Rh 52.6±3.5 | |||

| Aripiprazole | 9.03±0.12 | 8.96±0.14 | 8.80±0.13 | 8.56±0.13 |

| Dopamine | pKh 7.10±0.20 | pKh 7.73±0.19 | 5.38±0.14 (3) | |

| pKl 5.40±0.09 | 5.28±0.07 | pKl 5.68±0.16 | ||

| %Rh 42.4±3.1 | %Rh 49.5±5.5 | |||

| pKh 6.48±0.13 | ||||

| pKl 5.02±0.12** | ||||

| %Rh 54.4±3.0 (4) | ||||

| (−)-3-PPP | pKh 7.34±0.13 | |||

| 6.47±0.08 | 6.23±0.07 | pKl 5.77±0.16* | 5.63±0.16* | |

| %Rh 51.9±4.3 | ||||

| UH-232 | 7.23±0.06 | 7.14±0.06 | 6.62±0.07* | 6.03±0.05*,** |

Abbreviations: AJ-76, (1S,2R)-cis-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(N-propylamino)tetralin; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary; GTP, guanine 5′-triphosphate; NMDG, N-methyl D-glucamine.

The binding of drugs to D2 dopamine receptors in membranes of CHO cells expressing the D2 receptor was determined in competition versus [3H]spiperone binding as described in the Materials and methods. Experiments were performed under four different conditions: in the presence of Na+ (100 mM) or NMDG (100 mM), with and without GTP (100 μM). Data were fitted to one- and two-binding site models and the best-fit data are given (pKi for a one-binding site fit and pKh, pKl and %Rh for a two-binding site fit, for dopamine (+NMDG, +GTP) three experiments were fitted best by a one-binding site model and four by a two-binding site model). Data are given as mean±s.e.m. from at least three experiments.

P<0.05 for effect of Na+

P<0.05 for effect of GTP.

For (−)-3-PPP, competition curves in the presence of sodium ions were fitted best by a one-binding site model and there was no effect of GTP (Table 2). In the presence of NMDG, however, competition curves fitted well to a two-binding site model in the absence of GTP and a one-binding site model in the presence of GTP. Comparison of the Ki values in the presence of GTP showed that there was a significant (∼5-fold) increase in the affinity of binding of this ligand in the presence of sodium ions. Similar data were observed for aplindore, although this compound had a much higher affinity for the receptor than (−)-3-PPP and some receptor/G-protein coupling was seen in the presence of sodium ions (Table 2). For dopamine, (−)-3-PPP and aplindore, it seems that removal of sodium ions increases receptor/G-protein coupling.

For AJ-76, aripiprazole (Figure 4b) and UH-232 (Figure 4c), a one-binding site model provided the best description of data under all conditions. Binding data for aripiprazole were similar whether sodium ions or GTP were present so that this compound was insensitive to the effects of these modulators. Both AJ-76 and UH-232 were sensitive to the effects of sodium ions, binding with higher affinity in the presence of sodium ions. Neither compound was sensitive to the effects of GTP in the presence of sodium ions, but UH-232 became slightly sensitive to GTP (P<0.05) when sodium ions were absent from the assays. For AJ-76, aripiprazole and UH-232, therefore, there was little evidence that receptor/G-protein coupling was increased following removal of sodium ions.

Binding of UH-232 was slightly sensitive to GTP in the absence of sodium ions but these observations do not conform to predictions of the ternary complex model. The effects of GTP on UH-232 binding in the absence of sodium ions are to induce a shift in the entire binding curve. Given that for some compounds the effects of GTP are to induce a loss of a high affinity population of coupled receptors, a shift in the entire binding curve would not be expected.

Agonist efficacy parameters

From the ligand binding and functional data, it was possible to compute values for the amplification ratio (Ki/EC50) for compounds under the two conditions (Table 3). This analysis showed that there was an increase in Ki/EC50 upon substitution of Na+ by NMDG for all compounds tested with the exception of aripiprazole. As this ratio is a measure of efficacy for the drugs concerned (Black and Leff, 1983; Gardner and Strange, 1998), this shows that efficacy has increased following removal of sodium ions independent of any effects on the binding of drugs to the receptor. For aripiprazole, values of Ki and EC50 were quite similar in the presence of NMDG suggesting little amplification of signal between ligand binding and effect.

Table 3.

Agonist efficacy parameters

| pKi (Na+, GTP) | EC50 (Na+) | Ki/EC50 | pKi (NMDG, GTP) | EC50 (NMDG) | Ki/EC50 (NMDG) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AJ-76 | 6.50 | 7.02 | 3.3 | 5.20 | 6.67 | 29.5 |

| Aplindore | 9.03 | 9.57 | 3.5 | 8.40 | 9.47 | 11.7 |

| Aripiprazole | 8.96 | — | — | 8.56 | 8.90 | 2.2 |

| Dopamine | 5.28 | 6.56 | 19.1 | 5.38 | 7.10 | 53.7 |

| (−)-3-PPP | 6.23 | 6.81 | 3.8 | 5.63 | 6.64 | 10.2 |

| UH-232 | 7.14 | — | — | 6.03 | 7.34 | 20.4 |

Abbreviations: AJ-76, (1S,2R)-cis-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(N-propylamino)tetralin; EC50, median effective concentration; GTP, guanine 5′-triphosphate; NMDG, N-methyl D-glucamine; (−)-3-PPP, S-(−)-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-N-propylpiperidine hydrochloride; UH-232, cis-(+)-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(di-N-propylamino)tetralin.

Discussion

There is much current interest in the development of low efficacy partial agonists as drugs acting via the D2 dopamine receptor. It has been suggested that these may act as dopamine stabilizers, thus providing a novel treatment for schizophrenia (Carlsson et al., 2001). It is, however, quite difficult to assess the relative efficacies of such compounds on a spectrum of efficacy, as they lie close to the neutral point distinguishing agonism and inverse agonism. This means that on many assay protocols they will appear as antagonists and it will be difficult to disentangle underlying efficacy differences between compounds, as they will be silent under these conditions. One of the more popular assay systems used at present is the [35S]GTPγS binding assay where agonists stimulate binding of this non-hydrolysable analogue of GTP to the G protein.

In preliminary experiments, we tested aripiprazole, a candidate dopamine stabilizing drug under standard assay conditions (+GDP, +Na+) using this assay system and we found that it indeed was virtually silent. If, however, the sodium ions are removed and replaced by NMDG, as a cation substitute, then aripiprazole is able to elicit a net stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding. Given that the response to dopamine is somewhat diminished under these conditions, this translates into a substantial efficacy relative to dopamine.

We then tested a series of compounds in this format and found that in general the removal of sodium ions in this way increased actual and relative efficacy. The effect did not seem to be proportional and for five compounds (aripiprazole, AJ-76, UH-232, (−)-3-PPP, aplindore), the difference in relative efficacy was 40–70%. These are large effects on relative efficacy and they also correspond to effects on actual efficacy, that is, an increase in [35S]GTPγS binding at the 30 min time point. Indeed, for some of the compounds – AJ-76, aripiprazole and UH-232 – there is little or no stimulation in the presence of Na+ (AJ-76 in fact exhibits inverse agonism) but a significant stimulation when Na+ is substituted by NMDG. We also checked whether the time courses of stimulation of [35S]GTPγS binding were different for different agonists and under the different ionic conditions. In fact, the time courses were similar with similar rate constants but different maximal effects and initial rates of [35S]GTPγS binding (in fmol min−1 mg−1). This means that it is valid to compare efficacies of agonists based on a single (30 min) determination of [35S]GTPγS binding.

Basal [35S]GTPγS binding is increased by ∼40% by substitution of Na+ by NMDG. There is a small effect of the inverse agonist (+)-butaclamol to inhibit basal [35S]GTPγS binding under these conditions so there may be an increase in constitutive activation of the receptor although this seems to account for only a small proportion of the increase in basal [35S]GTPγS binding. Recent discussions of agonist efficacy have emphasized effects of the level of constitutive activation in a receptor system on the response seen for different compounds (Kenakin, 2004). Increased constitutive activation will tend to reduce agonist responses and increase inverse agonist responses and some compounds may switch from being partial agonists to inverse agonists (so-called protean agonists). In the present study, there may be some increase in constitutive activation following removal of sodium ions but for several compounds this leads to increased agonist responses and, for one compound (AJ-76), there is a switch from inverse agonism to partial agonism. It seems that in the present system, the effect of removal of sodium ions is to change the ability of the receptor to signal, rendering it more easily activated by compounds binding to it. This seems to be a specific effect of the substitution of Na+ by NMDG as substitution by K+ or Li+ does not have the same effect.

Empirically, therefore, the substitution of Na+ by NMDG increases the sensitivity of the assay to detect low efficacy partial agonists. We examined whether the effect of substitution of sodium ions resulted from a general increase in the affinity of agonist binding or increased receptor/G-protein coupling. Receptor/G-protein coupling was examined from the shapes of agonist binding curves, the occurrence of two agonist binding sites indicating receptor/G-protein coupling, and by disrupting coupling by addition of GTP. Although sodium ions did affect agonist binding, effects of sodium ions were different for different compounds and could not account for the increase in relative efficacy seen in signalling assays. There were, however, indications that receptor/G-protein coupling for some agonists (dopamine, aplindore, (−)-3-PPP) was stronger in the absence of sodium ions, and this effect of sodium ions has been suggested before for opioid receptors (Costa et al., 1992). For other agonists (AJ-76, aripiprazole, UH-232), there was little evidence of increased receptor/G-protein coupling in the absence of sodium ions. Therefore, for some compounds the increase in relative efficacy may be associated with enhanced receptor/G-protein coupling, for other compounds the effect must be mediated at a point in the G-protein cycle distal from formation of the coupled state (Roberts et al., 2004a). As another index of agonist signalling, the Ki/EC50 ratio (amplification ratio, (Black and Leff, 1983; Gardner and Strange, 1998)) was determined for the different compounds. Ki/EC50 values were generally higher when NMDG was substituted for Na+, supporting a general increase in efficiency of signalling. An exception here was aripiprazole, for which even in the presence of NMDG, the Ki/EC50 was low. The disparate effects seen here in these different measures of agonism (ligand binding, signalling, Ki/EC50) are consistent with different agonists inducing different conformations of the receptor (Strange, 1999; Kenakin, 2004).

Overall, the observations reported here provide a means of increasing signalling by low efficacy agonists at the D2 dopamine receptor so that they may be detected more readily in [35S]GTPγS binding assays. The method may have some generality as removal of sodium ions has been shown to increase relative efficacy of partial agonists at the μ-opioid receptor in this assay system (Selley et al., 2000). In the present set of experiments, the largest effects seen are on the very low efficacy agonists, for example, aripiprazole, UH-232, AJ-76, (−)-3-PPP, aplindore. This group of five compounds, whose efficacy is affected by removal of Na+ from assays, may be divided into two mechanistically separate subgroups. (−)-3-PPP and aplindore have significant efficacy in the presence of Na+ and for both compounds there is a clear increase in receptor/G-protein coupling in the absence of Na+ as shown in the ligand binding assays. For dopamine, there is evidence that receptor/G-protein coupling increases in the absence of Na+, hence (−)-3-PPP and aplindore are behaving similarly to dopamine only they possess lower intrinsic efficacy. Aripiprazole, AJ-76 and UH-232 have little or no agonist efficacy in the presence of Na+ and there is little evidence that for these compounds receptor/G-protein coupling increases upon removal of Na+. These compounds, therefore, appear to be mechanistically different. Aripiprazole has been reported to be a partial agonist or an antagonist in different in vitro assay protocols (Burris et al., 2002; Shapiro et al., 2003) and the compound suppresses prolactin secretion in humans indicating agonism (Swainston Harrison and Perry, 2004). UH-232 and AJ-76 have been reported to exhibit various effects in in vivo assays including antagonistic effects on presynaptic D2 receptors but not postsynaptic receptors (Svensson et al., 1986b), elevation of prolactin secretion indicating antagonism (Svensson et al., 1986a) and unexpected effects on cocaine stimulation (Piercey et al., 1992). In vitro, UH-232 has been reported to be a neutral antagonist, a partial agonist or an inverse agonist (Coldwell et al., 1999; Wilson et al., 2001; Gazi et al., 2003). The efficacy that these compounds express is, therefore, very dependant on the assay system used. The method described in this report whereby there is a large increase in relative efficacy when the relative efficacies of the compounds are compared with and without Na+ may provide a means of identifying such compounds.

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the financial support of the University of Reading, Martyn Wood (GSK) and Menes Pangalos (Wyeth) for generous supplies of some drugs and Suleiman Al-Sabah, Cornelius Krasel and Kate Quirk for very helpful comments on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AJ-76

(1S,2R)-cis-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(N-propylamino)tetralin

- [35S]GTPγS

guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate

- NMDG

N-methyl D-glucamine

- (−)-3-PPP

S-(−)-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-N-propylpiperidine hydrochloride

- UH-232

cis-(+)-5-methoxy-1-methyl-2-(di-N-propylamino)tetralin

References

- Armstrong D, Strange PG. Dopamine D2 receptor dimer formation: evidence from ligand binding. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22621–22629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006936200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JW, Leff P. Operational models of pharmacological agonism. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1983;220:141–162. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1983.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris KD, Molski TF, Xu C, Ryan E, Tottori K, Kikuchi T, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:381–389. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson A, Waters N, Holm-Waters S, Tedroff J, Nilsson M, Carlsson ML. Interactions between monoamines, glutamate, and GABA in schizophrenia: new evidence. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:237–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro SW, Strange PG. Differences in the ligand binding properties of the short and long versions of the D2 dopamine receptor. J Neurochem. 1993;60:372–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb05863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Prusoff WH. Relationship between the inhibition constant (K1) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell MC, Boyfield I, Brown AM, Stemp G, Middlemiss DN. Pharmacological characterization of extracellular acidification rate responses in human D2(long), D3 and D4.4 receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127:1135–1144. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa T, Ogino Y, Munson PJ, Onaran HO, Rodbard D. Drug efficacy at guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein-linked receptors: thermodynamic interpretation of negative antagonism and of receptor activity in the absence of ligand. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:549–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B, Strange PG. Agonist action at D2(long) dopamine receptors: ligand binding and functional assays. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:978–984. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazi L, Wurch T, Lopez-Gimenez JF, Pauwels PJ, Strange PG. Pharmacological analysis of a dopamine D(2Short):G(alphao) fusion protein expressed in Sf9 cells. FEBS Lett. 2003;545:155–160. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00520-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady MA, Gasperoni TL, Kirkpatrick P. Aripiprazole. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:427–428. doi: 10.1038/nrd1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Efficacy as a vector: the relative prevalence and paucity of inverse agonism. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:2–11. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry O, Rosebrough N, Farr A, Randall R. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGavin JK, Goa KL.Aripiprazole CNS Drugs 200216779–786.(discussion 787–778) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunnari JM, Repaske MG, Brandon S, Cragoe EJ, Jr, Limbird LE. Regulation of porcine brain alpha 2-adrenergic receptors by Na+,H+ and inhibitors of Na+/H+ exchange. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12387–12392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne SL, Johansson AM, Strange PG. Mechanisms of ligand binding and efficacy at the human D2(short) dopamine receptor. J Neurochem. 2002;82:1106–1117. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piercey MF, Lum JT, Hoffmann WE, Carlsson A, Ljung E, Svensson K. Antagonism of cocaine's pharmacological effects by the stimulant dopaminergic antagonists, (+)-AJ76 and (+)-UH232. Brain Res. 1992;588:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potkin SG, Saha AR, Kujawa MJ, Carson WH, Ali M, Stock E, et al. Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with a novel mechanism of action, and risperidone vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:681–690. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DJ, Lin H, Strange PG. Mechanisms of agonist action at D2 dopamine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2004a;66:1573–1579. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DJ, Lin H, Strange PG. Investigation of the mechanism of agonist and inverse agonist action at D2 dopamine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004b;67:1657–1665. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selley DE, Cao CC, Liu Q, Childers SR. Effects of sodium on agonist efficacy for G-protein activation in mu-opioid receptor-transfected CHO cells and rat thalamus. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:987–996. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selley DE, Sim LJ, Xiao R, Liu Q, Childers SR. mu-Opioid receptor-stimulated guanosine-5′-O-(gamma-thio)-triphosphate binding in rat thalamus and cultured cell lines: signal transduction mechanisms underlying agonist efficacy. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:87–96. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, Chiodo LA, Liu LX, Sibley DR, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:1400–1411. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit MJ, Leurs R, Alewijnse AE, Blauw J, Van Nieuw Amerongen GP, Van De Vrede Y, et al. Inverse agonism of histamine H2 antagonist accounts for upregulation of spontaneously active histamine H2 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6802–6807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strange PG. G-protein coupled receptors: conformations and states. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:1081–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson K, Carlsson M, Carlsson A, Hjorth S, Johansson AM, Eriksson E. The putatively selective dopamine autoreceptor antagonists (+)-AJ 76 and (+)-UH 232 stimulate prolactin release in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1986a;130:237–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson K, Johansson AM, Magnusson T, Carlsson A. AJ 76 and (+)-UH 232: central stimulants acting as preferential dopamine autoreceptor antagonists. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1986b;334:234–245. doi: 10.1007/BF00508777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swainston Harrison T, Perry CM. Aripiprazole: a review of its use in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Drugs. 2004;64:1715–1736. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J, Lin H, Fu D, Javitch JA, Strange PG. Mechanisms of inverse agonism of antipsychotic drugs at the D(2) dopamine receptor: use of a mutant D(2) dopamine receptor that adopts the activated conformation. J Neurochem. 2001;77:493–504. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]