Abstract

Aims

To examine whether the antidepressant venlafaxine, a novel serotonin-noradrenaline re-uptake inhibitor (SNRI), can modify α-adrenoceptor-mediated venoconstriction in man. The effects of venlafaxine were compared with those of desipramine, a tricyclic antidepressant with noradrenaline uptake inhibiting properties, and paroxetine, a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI), on noradrenaline-and methoxamine-evoked venoconstriction using the dorsal hand vein compliance technique.

Methods

Fifteen healthy male volunteers participated in five weekly experimental sessions. Each session was associated with a clinically effective dose of an antidepressant or placebo. The following oral dosages were used: venlafaxine 75 mg, venlafaxine 150 mg, desipramine 100 mg, paroxetine 20 mg, or placebo. A double-blind, cross-over, balanced design was used. In each session, dose–response curves to both locally infused noradrenaline acid tartrate (0.1–33.33 ng min−1) and methoxamine hydrochloride (0.5–121.5 μg min−1) were constructed. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure and pulse rate were measured in the supine and erect positions. Salivation was measured by the dental roll technique.

Results

Venlafaxine 150 mg and desipramine 100 mg potentiated the venoconstrictor response to noradrenaline (anova of log ED50s: P < 0.01; individual comparisons: venlafaxine 150 mg vs placebo: P < 0.005; mean difference, 95% CI: −0.49 (−0.81, −0.17); desipramine 100 mg vs placebo: P < 0.005; mean difference, 95% CI: −0.34 (−0.60, −0.09) without affecting the response to methoxamine. Neither paroxetine nor placebo had any effects on the venoconstrictor responses. Both doses of venlafaxine increased systolic blood pressure (supine and erect) and venlafaxine 150 mg increased diastolic blood pressure (supine) (anova, P < 0.05). Desipramine increased heart rate (P < 0.05). Desipramine and both doses of venlafaxine reduced salivation (P < 0.025).

Conclusions

These results show that, similarly to desipramine 100 mg, venlafaxine 150 mg can potentiate venoconstrictor responses to noradrenaline, consistent with venlafaxine’s ability to block noradrenaline uptake in man. The importance of noradrenaline uptake blockade in these observations is confirmed by the lack of effect of the antidepressants on methoxamine-evoked venoconstriction and the failure of paroxetine to modify noradrenaline-evoked venoconstriction.

Keywords: α1-adrenoceptors, desipramine, dorsal hand vein, paroxetine, venlafaxine

Introduction

Venlafaxine is a bicyclic phenylethylamine derivative with a pharmacological profile that differentiates it from tricyclic antidepressants and serotonin uptake inhibitors. It is a serotonin and noradrenaline uptake inhibitor (SNRI) with a weak effect on dopamine uptake [1, 2]. It lacks anticholinergic, antiadrenergic, antiserotonergic and antihistaminergic effects [3]. Venlafaxine has no inhibitory effects on monoamine oxidase A or B [1]. As venlafaxine has a somewhat higher affinity for serotonin re-uptake than for noradrenaline re-uptake [1, 4], it is believed that at lower dosage levels it acts mainly as a serotonin re-uptake inhibitor. At higher dosage level, however, it is believed that it exerts an additional noradrenaline re-uptake inhibition. This has been thought to account for the increased efficacy of venlafaxine in severely depressed patients [5, 6].

At present, however, it is not known whether venlafaxine inhibits noradrenaline re-uptake in clinically used doses in man. The present experiment addressed this question by comparing the influence of venlafaxine and inhibitors of noradrenaline and serotonin re-uptake on α-adrenoceptor-mediated venoconstriction induced by noradrenaline, which is subject to re-uptake, and methoxamine, which is not subject to re-uptake. The effects of venlafaxine (75 mg and 150 mg), desipramine (100 mg), and paroxetine (20 mg) on constrictor responses of the dorsal hand vein to locally infused noradrenaline and methoxamine were studied, using the dorsal hand vein compliance technique [7]. Some of these results have been communicated to the British Association for Psychopharmacology [8].

Methods

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the University of Nottingham Medical School Ethics Committee. All volunteers gave their written informed consent following a verbal explanation of the study and after reading a detailed information sheet.

Subjects

The study was conducted in 15 healthy male volunteers aged 20–28 years (mean±s.e.mean, 22.0±1.0) and weighing 57–105 kg (mean±s.e.mean, 76.4±5.8). Each subject completed a brief medical history and underwent a physical examination. Subjects had not participated in drug studies within 3 months prior to the start of the present study, and had not used any drug the preceding 14 days. They were requested to stop smoking and not to drink alcohol, coffee and other caffeine-containing beverages for at least 12 h before each session. All subjects were advised to have a light meal 2 h before the sessions. All subjects indicated compliance with these requests. All subjects had normal urine analysis, negative urine screens for drugs of abuse, complete blood count, liver and kidney function tests, and ECG.

Drugs

Noradrenaline acid tartrate (Levophed®) was obtained from Sanofi-Winthrop, Guildford, Surrey, UK, methoxamine hydrochloride (Vasoxine®) from the Wellcome Foundation, London, UK, venlafaxine hydrochloride was obtained from Wyeth, Berks, UK, desipramine hydrochloride (Pertofran®) from Geigy Pharmaceuticals, Horsham, West Sussex, UK, paroxetine hydrochloride was obtained from SmithKline Beecham, Weybridge, Surrey, UK. The sterile solutions of noradrenaline acid tartrate and methoxamine hydrochloride were diluted in 5% dextrose saline and administered locally into the vein at a constant rate of 0.3 ml min−1 and over the following dose ranges: noradrenaline acid tartrate 0.10–33.33 ng min−1; methoxamine hydrochloride 0.5–121.5 μg min−1. Clinically effective single doses of venlafaxine (75 and 150 mg), desipramine (100 mg) and paroxetine (20 mg), and lactose placebo were prepared in identical capsules suitable for double-blind administration by the Queen’s Medical Centre Pharmacy Department.

Experimental design

Subjects were allocated to treatments and sessions according to a double-blind balanced design. Each volunteer participated in five experimental sessions at weekly intervals, each session being associated with one of the following systemic oral treatments: venlafaxine 75 mg; venlafaxine 150 mg; desipramine 100 mg; paroxetine 20 mg, or placebo. In each session, dose–response curves to locally infused noradrenaline and methoxamine were constructed.

At the beginning of each session, the subject rested for 30 min and then the pretreatment tests were carried out (i.e. supine and standing heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and salivation). In each session the subject ingested two capsules: the first one after the pretreatment tests, and the second one 80 min later. In the venlafaxine sessions the first capsule was a dummy and the second one contained the active drug, whereas in the desipramine and paroxetine sessions the first capsules contained the active drugs. Baseline venous diameter was recorded for a period of approximately 30 min between 195 min and 225 min following the ingestion of the first capsule, until two equal readings were obtained. After the baseline venous diameter had been recorded, the local infusion of six doses of the agonists, first noradrenaline and then methoxamine, commenced; each dose was applied for 5–7 min. Supine and standing heart rate, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements were carried out on two occasions in each session: before and 180 min after the ingestion of the first capsule. Supine heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured before the infusion of noradrenaline and after the infusion of the highest dose of noradrenaline, before the infusion of methoxamine and after the infusion of the highest dose of methoxamine. Salivation was measured before the ingestion of the first capsule and 180 min later.

The timings of start of the local infusion and of the post-treatment tests were based on the single-dose pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine [9], desipramine [10], and paroxetine [11], to ensure that testing took place at the peak plasma concentration of the drugs. It has been shown that the time required to attain the peak plasma concentration after a single oral dose is shorter for venlafaxine (1–3 h) than for desipramine (3–6 h) and paroxetine (3–8 h). Therefore, the time-interval between drug ingestion and the beginning of post-treatment testing was chosen to be 1 h 20 min for venlafaxine, and 3 h for desipramine and paroxetine. Furthermore, the rather long elimination half-lives of the antidepressants (venlafaxine: 3–6 h, desipramine: 16–35 h, paroxetine: 4–65 h) ensured that the plasma levels of the drugs remained relatively constant during the time window of postdrug testing.

Tests

The dorsal hand vein compliance technique

The dorsal hand vein compliance technique, as modified by Aellig [7], was used as described previously [12]. In brief, the subject lay supine at a room temperature of 22–24° C. One arm was placed on a padded support sloping upwards at an angle of 30° from the horizontal to ensure complete emptying of the superficial hand veins. A 27-gauge butterfly needle was inserted into a suitable dorsal hand vein and a continuous infusion of 5% dextrose saline was started by a Vial Medical pump (Vial Medical Ltd, Southampton, UK) at a rate of 0.3 ml min−1. The linear variable differential transducer (LVDT) was then mounted onto the back of the hand over the summit of the vein under investigation. The LVDT (Schaevitz Engineering, Pennsauken, NJ, USA; model 100 MHR) was held in place by a small square perspex block which was fastened to the skin with four adhesive pads. The LVDT’s freely moveable core, weighing 0.5 g, was placed over the centre of the vein under study approximately 10 mm proximally from the tip of the needle. When the core was properly centred within the transducer there was a linear relationship over the range employed between the vertical movement of the core and the voltage output which was recorded on a strip chart recorder and computer screen. After insertion of the needle, recordings of the position of the core situated over the top of the vein were made both before and after inflation of a sphygmomanometer cuff on the ipsilateral upper arm to 45 mmHg, at 10 min intervals until two equal readings were obtained. This baseline vasodilatation during saline infusion with the cuff inflated was taken as ‘100% relaxation’ (or ‘0% constriction’); the recording obtained with the cuff deflated (and the vein emptied) was taken as ‘100% constriction’. The difference between the two positions of the core gave a measure of the diameter changes of the vein under the congestion pressure of 45 mmHg. Each period of drug infusion consisted of an initial 3 min with the cuff deflated, followed by a further 2–4 min with the cuff inflated (i.e. a sufficient period of time to ensure that the venous diameter had reached a plateau). Increasing concentrations of the agonist were given at a constant infusion rate (0.3 ml min−1). A washout period of 15 min was allowed between the infusions of the highest dose of noradrenaline and the first dose of methoxamine by switching to a separate infusion pump connected to the system. Care was taken to cannulate the same vein in each subject in each successive session. In each experiment, vein size returned to baseline during the washout period. Blood pressure and pulse rate were monitored at frequent intervals (see below) on the contra-lateral arm.

Blood pressure and pulse rate

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured using a mercury sphygmomanometer, and heart rate by feeling the pulse of the radial artery at the wrist for 1 min. These measurements were carried out when the subjects were lying and after they had been standing for 1 min. All measurements were taken on the arm opposite to the one used for the pharmacological testing, before and after treatment with the systemically administered drug; the difference between pre- and post-treatment measurements was taken as the effect of the drug.

Salivary test

Salivation was measured using the dental roll method [13]. Three cotton-wool rolls (size 2) were placed in the mouth for 1 min, two buccally and one sublingually, and the increase in weight was measured. The mean of three measurements taken at 5 min intervals was used for analysis, and pre/post-treatment differences were calculated to determine the effects of systemically administered drugs.

Data analysis

Dorsal hand vein responses

The data obtained with the two locally infused agonists were analysed separately. The raw data were analysed with two-way analysis of variance (dose of agonist; systemic drug treatment) with repeated measures on both factors. When a significant main effect of drug treatment was identified, individual comparisons were made between placebo and each dose of venlafaxine, desipramine, and paroxetine with Dunnett’s test (d.f.=56; k=5; criterion P < 0.05). The individual dose–response curves obtained in each subject were also analysed to estimate the maximal response (Emax) and the dose producing the half-maximal response (ED50), using a computer programme based on Wilkinson’s method [14]. This analysis also provided the index of determination (p2) for each curve; p2 expresses the proportion of the data variance accounted for by the fitted function [15]. The distribution of the ED50 values was normalized by logarithmic transformation, and the geometric mean for the group of 15 subjects was calculated for the five dose–response curves for both noradrenaline and methoxamine. Analysis of variance with repeated measures and Dunnett’s test were used to compare the effects of venlafaxine (both doses), desipramine, paroxetine, and placebo on Emax and log ED50. Mean differences (and 95% CI) between the values of these parameters in the presence of placebo and each dose of venlafaxine, desipramine, and paroxetine were derived. The degree of antagonism or potentiation of the responses by systemic drug treatments was expressed by the dose-ratio, which was calculated by taking the antilog of mean change in log ED50. A similar procedure was used to calculate the potency ratio of the two agonists (noradrenaline/methoxamine).

Salivary output and cardiovascular measures

Analysis of variance with repeated measures, and Dunnett’s test were used to compare the effects of the systemic treatments on salivary output and cardiovascular measures.

Results

Dorsal hand vein responses

Base-line venous diameter

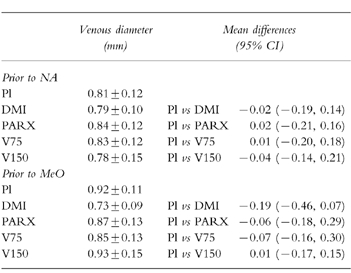

There were no significant differences between the venous diameters recorded in the placebo sessions prior to the application of noradrenaline and methoxamine (mean difference, 95% CI: 0.02 (−0.14, 0.09)) (Table 1). Furthermore, baseline venous diameter was not affected by any of the treatments, either prior to the infusion of noradrenaline (F4,56 =0.11, P =NS) or prior to the infusion of methoxamine (F4,56 =0.83, P =NS).

Table 1.

Baseline venous diameter (mm; mean±s.e.mean, n =15) at a congestion pressure of 45 mmHg after the ingestion of placebo (Pl), desipramine (DMI, 100 emsp14;mg), paroxetine (PARX, 20 mg), and venlafaxine (75 mg (V75), and 150 mg (V150)) prior to the local infusion of noradrenaline (NA) and methoxamine (MeO). Right-hand column shows mean differences (95% CI) between records obtained after placebo and active drug treatments.

Effects of agonists

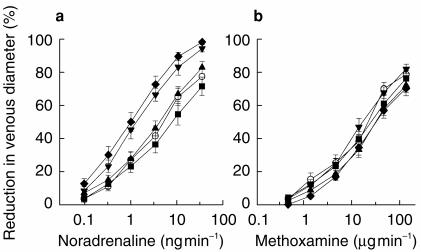

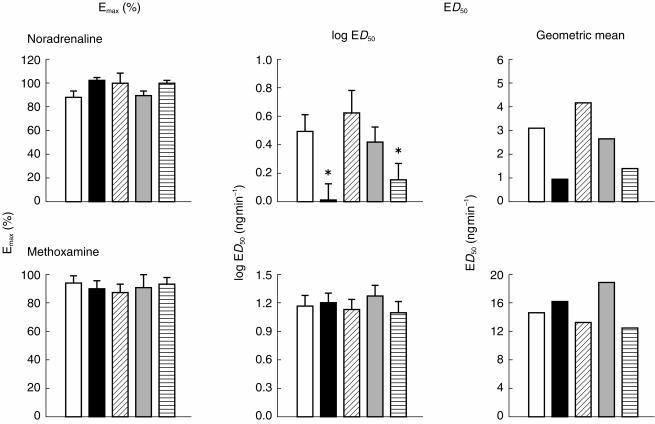

Both noradrenaline and methoxamine produced dose-related venoconstriction (Figure 1). The median proportion of the data variance accounted for by the dose–response functions fitted to the individual subject data was 0.97 for both noradrenaline and methoxamine. In order to compare the relative potencies of noradrenaline and methoxamine, the ED50 value for each agonist was expressed in nmol min−1; the geometric mean ED50 was 0.02 nmol min−1 for noradrenaline and 59.04 nmol min−1 for methoxamine; and the potency ratio (noradrenaline/methoxamine) was 2952 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Dose–response curves for the venoconstrictor effect of noradrenaline (a) and methoxamine (b) during local infusion into the superficial dorsal hand vein (occlusion pressure 45 mmHg) 195 min after the ingestion of placebo (○), desipramine 100 mg (♦), and paroxetine 20 mg (▪), and 115 min after the ingestion of venlafaxine 75 mg (▴), and venlafaxine 150 mg (▾); mean±s.e.mean n =15.

Figure 2.

Parameters of the dose–response curves (Emax: left, log ED50: middle, Geometric mean: right) to noradrenaline (upper panel) and methoxamine (lower panel) (n =15), calculated from individual subject data, 195 min after ingestion of placebo (open), desipramine 100 mg (black), and paroxetine 20 mg (oblique lines), and 115 min after ingestion of venlafaxine 75 mg (grey), and venlafaxine 150 mg (horizontal lines). *P < 0.005 (Analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s test).

Interactions between agonists and venlafaxine, desipramine and paroxetine

Noradrenaline

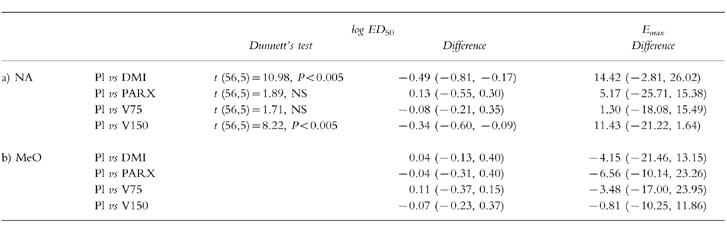

(Figure 1). Analysis of variance showed significant main effects of both dose of noradrenaline (F5,70 =377.39, P < 0.0001) and of the systemic drug treatment (F4,56 =12.98, P < 0.0001), and a significant interaction (F(20,280)=3.59, P < 0.0001). Desipramine (100 mg) and venlafaxine (150 mg) potentiated noradrenaline-evoked venoconstriction, however, venlafaxine (75 mg) and paroxetine (20 mg) had no significant effects (Dunnett’s test). In the case of the individually fitted curves (n =15) the median values of p2 were 0.97 (venlafaxine 75 and 150 mg), 0.98 (desipramine 100 mg), 0.94 (paroxetine 20 mg), and 0.97 (placebo). There was a statistically significant effect of treatment on log ED50 (F4,56 =5.74, P < 0.0025) but not on Emax (F4,56 =1.50, NS) (Figure 2). Table 2 contains the individual comparisons of each active treatment with placebo (mean differences, 95% CI; Dunnett’s test in cases of significant treatment main effects). The difference (%; mean±s.e.mean) between the estimated value of Emax and the response evoked by the highest dose of noradrenaline, for all subjects in all treatment conditions, was 9.25±1.75. There were statistically significant differences between the values of log ED50 in the presence of venlafaxine (150 mg) and placebo, and in the presence of desipramine and placebo. The dose ratios were 0.32, 0.46, 0.86, and 1.34 for desipramine (100 mg), venlafaxine (150 mg), venlafaxine (75 mg), and paroxetine (20 mg), respectively. Table 2 shows the differences (mean, 95% CI, n =15) in the values of log ED50 and Emax between placebo and venlafaxine (150 mg), venlafaxine (75 mg), desipramine (100 mg) and paroxetine (20 mg), in the noradrenaline sessions.

Table 2.

Comparison of the parameters of the dose–response curves to (a) noradrenaline (NA; log ED50: ng min −1, Emax: %) and to (b) methoxamine (MeO; log ED50: μg min −1, Emax: %), in the presence of placebo and the active drug treatments (c.f. Figure 2). Dunnett’s test ( d.f., k) in case where there was a significant treatment main effect (see text for details); differences (mean, 95% CI, n =15) between placebo and active treatments.

Methoxamine

(Figure 1). Analysis of variance with repeated measures showed a significant effect of the dose of methoxamine (F5,70 =368.41, P < 0.0001), but not of systemic drug treatment (F4,56 =2.12, NS). In the case of the individually fitted curves (n =15) the median values of p2 were 0.98 (venlafaxine 75 mg), 0.99 (venlafaxine 150 mg), 0.98 (desipramine 100 mg), 0.98 (paroxetine 20 mg), and 0.97 (placebo). The systemic treatments had no effect on either log ED50 or Emax (log ED50: F4,56 =0.53, NS; Emax: F4,56 =0.26, NS) (Figure 2). The difference (%; mean±s.e.mean) between the estimated value of Emax and the response evoked by the highest dose of methoxamine, for all subjects in all treatment conditions, was 12.15±2.60. The dose ratios were 1.10, 0.85, 1.29, and 0.91 for desipramine (100 mg), venlafaxine (150 mg), venlafaxine (75 mg), and paroxetine (20 mg), respectively. Table 2 shows the comparison of the parameters of the dose response curve, in the presence of placebo and active treatments (mean differences, 95% CI).

Blood pressure and heart rate

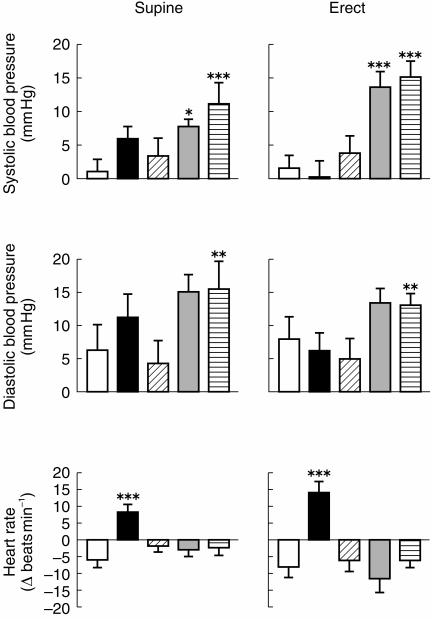

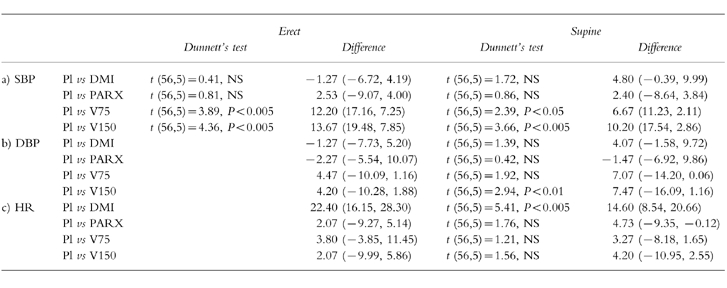

Compared with placebo, venlafaxine 75 mg and 150 mg produced significant increases in systolic blood pressure in both supine and erect position; venlafaxine 150 mg also increased diastolic blood pressure in the supine position; desipramine 100 mg produced significant increases in heart rate in both postures (Figure 3; see Table 3 for statistical analysis).

Figure 3.

Cardiovasular measures. Change from pretreatment, mean±s.e.mean, n =15, 180 min after placebo (open), desipramine 100 mg (black), and paroxetine 20 mg (oblique lines), and 100 min after oral ingestion of venlafaxine 75 mg (grey), and venlafaxine 150 mg (horizontal lines). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 (Analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s test).

Table 3.

Comparison of cardiovascular measures: (a) systolic blood pressure (SBP, mmHg); (b) diastolic blood pressure (DBP, mmHg) and heart rate (HR, beats min−1) in the presence of placebo and the active drug treatments. Dunnett’s test (d.f., k) where there was a significant main effect (see text for details); differences (mean, 95% CI, n =15) between placebo (Pl) and active drug treatments (desipramine (100 mg, DMI), paroxetine (20 mg, PARX), venlafaxine (75 mg (V75), and 150 mg (V150)).

There were no significant changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate prior to the infusion of noradrenaline or methoxamine, and immediately after the infusion of the highest noradrenaline dose or the highest methoxamine dose (Student’s t-test; P >0.1 in each case).

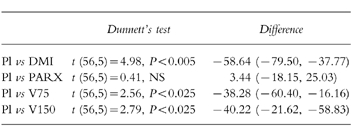

Salivation

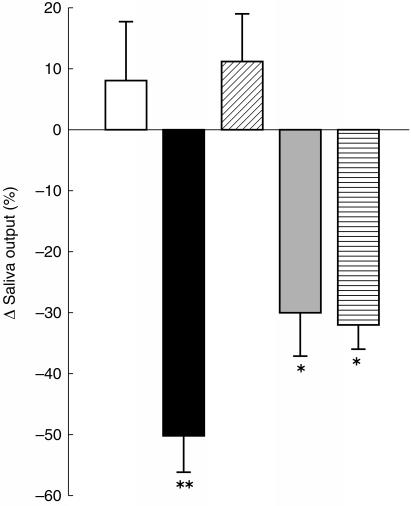

Compared with placebo, venlafaxine 75 mg, venlafaxine 150 mg and desipramine 100 mg, produced significant reduction in salivation (Figure 4; see Table 4 for statistical analysis).

Figure 4.

Change in salivary output 180 min after ingestion of placebo (open), desipramine 100 mg (black), and paroxetine 20 mg (oblique lines), and 100 min after ingestion of venlafaxine 75 mg (grey), and venlafaxine 150 mg (horizontal lines). The columns show the percentage change from the pretreatment value, ±s.e.mean (n =15). *P < 0.025, **P < 0.005 (Analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s test).

Table 4.

Comparison of salivary output (% change from pretreatment), in the presence of placebo and the active drug treatments (desipramine (100 mg, DMI), paroxetine (20 mg, PARX), venlafaxine (75 mg (V75), and 150 mg (V150)). Dunnett’s test (d.f., k) and differences (mean, 95% CI, n =15) between placebo and active drug treatments.

Discussion

The results show, in agreement with a number of previous reports [12, 16, 17], that both noradrenaline and methoxamine constrict the dorsal hand vein in a reproducible dose-dependent manner and that methoxamine is a much less potent agonist than noradrenaline. There is evidence that the venoconstrictor response to the adrenoceptor agonists is mediated by α1-adrenoceptors [16, 18]: the selective synthetic α1-adrenoceptor agonists phenylephrine and methoxamine have venoconstrictor effects, and it has been shown that the responses to these agonists are antagonized by α1-adrenoceptor antagonists, such as prazosin and terazosin [19, 20].

In our experiment, in each session, the effects of both noradrenaline and methoxamine were studied on the same dorsal hand vein. Ideally, the order in which the two agonists are applied should be counter-balanced between sessions and treatments. This, however, was not possible since it takes a very long time for the vein to recover from methoxamine-induced venoconstriction, probably reflecting the fact that methoxamine is not eliminated by the noradrenaline uptake mechanism [21]. Indeed, it has been reported that the vein shows almost no relaxation for up to 35 min following the application of methoxamine [22]. On the other hand, the vein recovers completely within 10 min from the constrictor effect of noradrenaline [22]. It is unlikely that the prior application of noradrenaline would have interfered with the responses to methoxamine for the following reasons. Firstly, we have used 15 min washout periods between the applications of noradrenaline and methoxamine, and this washout period is well in excess of the period required for the recovery of the noradrenaline-induced constrictor response. Indeed, as shown in Table 1, the venous diameter did not differ prior to the application of methoxamine from that recorded prior to the application of noradrenaline. Secondly, we have shown previously that the prior application of noradrenaline, using the same washout period as in the present experiment, did not alter venoconstrictor responses to noradrenaline which, like the responses to methoxamine, are mediated by α1-adrenoceptors [23]. Finally, the responses to methoxamine remained relatively stable between different sessions, although the precedent responses to noradrenaline were considerably altered (i.e. potentiated) by some of the antidepressant treatments, indicating that changes in the responses to noradrenaline were not reflected in subsequent responses to methoxamine.

Both desipramine (100 mg), and venlafaxine (150 mg) potentiated the venoconstrictor response to noradrenaline, reflected in a leftward shift of the dose–response curve. The potentiation of the venoconstrictor response to noradrenaline is most likely to be due to the blockade of the uptake of noradrenaline by desipramine and the higher dose (150 mg) of venlafaxine. It is well documented that desipramine is a potent inhibitor of noradrenaline uptake [24], and there is a large body of evidence that desipramine can potentiate the pharmacological effects of noradrenaline [24]. Furthermore, we have been able to demonstrate that desipramine (100 mg) is capable of potentiating the constrictor responses of the dorsal hand vein in man to noradrenaline [12]. It has been shown that venlafaxine also possesses affinity for the noradrenaline uptake mechanism [25], and thus it could be predicted that it would potentiate the effects of noradrenaline in sympathetically innervated tissues. It is of interest that neither desipramine nor venlafaxine affected the venoconstrictor response to methoxamine, a drug which is not a substrate for the noradrenaline uptake mechanism [21], thus confirming the role of uptake inhibition in the potentiation of the venoconstrictor response by these two antidepressants.

The lower dose (75 mg) of venlafaxine failed to affect the venoconstrictor response to noradrenaline, suggesting that this dosage did not result in a tissue concentration sufficiently high to inhibit noradrenaline uptake to the extent required for potentiation. This observation is consistent with the proposal that at lower dosage levels venlafaxine acts mainly as a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) [26]. It should be mentioned, however, that venlafaxine 75 mg had some systemic effects in the present study, both in the cardiovascular system and salivary glands, which may reflect uptake blockade at some noradrenergic synapses (see below).

Paroxetine (20 mg), like the lower dose (75 mg) of venlafaxine, failed to modify the venoconstrictor response to noradrenaline. This observation is consistent with the pharmacological profile of the drug: while paroxetine is a potent inhibitor of serotonin uptake, it has little affinity for the noradrenaline uptake mechanism [27, 28]. Our observation of the effect of paroxetine on the noradrenaline uptake mechanism in the human vascular system is consistent with a previous report that a single dose of paroxetine (30 mg) failed to antagonize the tyramine-evoked reduction in forearm blood flow [29].

Methoxamine is not a substrate for the noradrenaline uptake mechanism [21], and thus a reduction in the size of the response to this α1-adrenoceptor agonist can be taken as an index of α1-adrenoceptor blockade [24]. The lack of effect of venlafaxine and paroxetine on the response to methoxamine is consistent with the very low affinities of these drugs for α1-adrenoceptors.

Both desipramine and venlafaxine had significant cardiovascular effects, whereas paroxetine was without any effect on cardiovascular functions. The most plausible explanation for the cardiovascular effects of desipramine and venlafaxine is that they reflect noradrenaline uptake blockade leading to sympathetic potentiation. Sympathetic potentiation would be expected to result both in an increase in heart rate and blood pressure. However, desipramine and venlafaxine had different effects on the cardiovascular measures, desipramine mainly increased heart rate, while venlafaxine increased blood pressure. The reason for the difference between the cardiovascular profiles of the two drugs may lie in the fact that desipramine also has some α1-adrenoceptor blocking property. Thus, in the case of desipramine, the depressor effect of α1-adrenoceptor blockade may counteract the pressor effect resulting from noradrenaline uptake blockade. On the other hand, in the case of venlafaxine, the pressor effect may manifest itself unimpeded, and the resultant reflex bradycardia may mask the cardio-accelerator effect of sympathetic potentiation. It should be pointed out that this hypothesis relies on the assumption that α1-adrenoceptors in the arterial system show greater sensitivity to blockade by desipramine than those in peripheral veins, since methoxamine-evoked constriction of the dorsal hand vein remained unaffected by desipramine in the present experiment. Indeed, there is evidence that both the distribution [30] and pharmacological sensitivity [31] of adrenoceptors may differ between the arterial and venous systems.

Desipramine and venlafaxine reduced salivary output showing clear pharmacodynamic effects outside the vascular system, while paroxetine was without effect. Desipramine caused a substantial (almost 50%) reduction in salivary output, a finding which is consistent with our previous observation [12], and numerous previous reports [24]. This effect of desipramine is generally attributed to the blockade of muscarinic cholinoceptors by the drug, although α1-adrenoceptor blockade may have accentuated it [24]. Salivary output was also significantly reduced, almost 30% and 32%, by venlafaxine (75 mg) and venlafaxine (150 mg), respectively. Indeed, dry mouth is one of the self-reported side-effects of venlafaxine in clinical trials [25]. The reduction in salivation by venlafaxine is a surprising finding since this drug has very low affinity both for muscarinic cholinoceptors and adrenoceptors. It is an intriguing possibility that the reduction in salivation produced by venlafaxine, and to some extent by desipramine, may reflect the reduced activity of parasympathetic salivary neurones in the brain stem resulting from the potentiation of the noradrenergic inhibition of these neurones due to noradrenaline uptake blockade. It is of interest that the selective noradrenaline uptake blocker reboxetine also reduces salivation, probably via the same mechanism [32]. There is anatomical evidence that the salivary nuclei receive a rich innervation from the propriobulbar noradrenergic fibres [33], and it is likely that these fibres activate inhibitory α2-adrenoceptors on the salivary neurones, as illustrated by the reduction in salivation induced by the α2-adrenoceptor agonist clonidine [34]. Our observation of a lack of effect of paroxetine (20 mg) on salivary output is in agreement with a previous report that paroxetine (30 mg) did not affect salivation [29]. This observation is consistent with the pharmacological profile of paroxetine, whose main action is the blockade of serotonin uptake, without appreciable effects on muscarinic cholinoceptors, α1-adrenoceptors or noradrenaline uptake.

In conclusion, the present results show that clinically relevant single doses of the novel antidepressant venlafaxine can potentiate the pharmacological effects of noradrenaline in the vascular system in man, consistent with the ability of the drug to block noradrenaline uptake. Furthermore, the effects of the drug in the cardiovascular system (i.e. increase in blood pressure) and on salivary glands (i.e. reduction in salivation) are also likely to be secondary to the inhibition of the uptake of noradrenaline into noradrenergic nerve terminals.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Wyeth Laboratories for financial support.

References

- 1.Muth EA, Haskins JT, Moyer JA. Antidepressant biochemical profile of the novel bicyclic compound Wy-45, 030, an ethyl cyclohexanol derivative. Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;35:4493–4497. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90769-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolden-Watson C, Richelson E. Blockade by newly-developed antidepressants of biogenic amine uptake into rat brain synaptosomes. Life Sci. 1993;52:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preskorn SH. Antidepressant drug selection: criteria and option. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:6–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richelson E. Pharmacology of antidepressants; characteristics of ideal drug. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 1994;69:1069–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeMontigny E, Preskorn SH. Comparison of the tolerability of bupropion, fluoxetine, imipramine, nefazadone, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(Suppl 6):12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preskorn SH. Clinical Pharmacology of SSRIS: the Basis for Their Optimal Use. Caddo, Oklahoma: Professional Communication Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aellig WH. A new technique for recording compliance of human hand veins. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;11:237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb00527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelmawla AH, Langley RW, Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM. Comparison of venlafaxine, desipramine, and paroxetine on the dorsal hand vein in man. J Psychopharmacol. 1997;11:28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klamerus KJ, Maloney K, Rudolph RL. Introduction of composite parameters to the pharmacokinetics of venlafaxine and its active metabolites O-desmethyl metabolites. J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;32:716–724. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1992.tb03875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallee FR, Pollock BG. Clinical pharmacokinetics of imipramine and desipramine. Clin Pharmacokin. 1990;18:346–364. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199018050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye CM, Haddock PF, Langley G, Mellows TCG, Zussman TBD, Greb WH. A review of the metabolism of paroxetine in man. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1989;80(Suppl 350):60–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb07176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abdelmawla AH, Langley RW, Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM. Comparison of the effects of desipramine on noradrenaline- and methoxamine-evoked venoconstriction in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;40:445–451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peck RE. The SHP test: an aid in the detection and measurement of depression. Arch Gen Psychiat. 1959;1:35–40. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1959.03590010051006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilkinson GN. Statistical estimations in enzyme kinetics. Biochem J. 1961;80:324–332. doi: 10.1042/bj0800324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis D. Quantitative Methods in Psychology. New York: Springer Berlin, Heidelberg; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulte KL, Laber E, Braun J, Meyer-Sabellek W, Distler A, Gotzen R. Nifedipine vasodilates human forearm arteries and dorsal hand veins constricted by specific α-adrenoceptor stimulation. Gen Pharmacol. 1987;18:525–529. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(87)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alradi AO, Carruthers SG. Evaluation and applications of the linear variable differential transformer technique for the assessment of human dorsal hand vein alpha-receptor activity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;38:495–502. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haefeli WE, Srivastava V, Kongpatanakul S, Blaschke TF, Hoffman BB. Lack of role of endothelium-derived relaxing factors in effects of α-adrenergic agonists in cutaneous veins in humans. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H364–H369. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.2.H364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belz GG, Beermann C, Schloos J, Kleinbloesem CH. The effects of oral cilazapril and prazosin on the constrictor effects of locally infused angiotensin I and noradrenaline in human dorsal hand veins. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:608–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent J, Dashman WD, Blaschke TF, Hoffman BB. Pharmacological tolerance to α-adrenergic receptor antagonism mediated by terazosin in humans. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:1763–1768. doi: 10.1172/JCI116050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trendelenburg U, Maxwell RA, Pluchino S. Methoxamine as a tool to assess the importance of intraneuronal uptake of l-norepinephrine in cat’s nictitating membrane. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970;172:91–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan HY, Hoffman BB, Persche RA, Blaschke TF. Differences in recovery from venoconstriction to α-agonists studied with the dorsal hand vein technique. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;37:219. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdelmawla AH, Langley RW, Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM. Cumulative and noncumulative dose response curves to noradrenaline on the dorsal hand vein. J Pharmacol Toxicol Meth. 1996;36:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(96)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM. Antidepressant drugs and the autonomic nervous system. In: Deakin JFW, editor. The Biology of Depression. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists/Gaskell; 1986. pp. 190–220. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muth EA, Moyer JA, Haskins JT, Andree TH, Husbands GEM. Biochemical, neurophysiological, and behavioural effects of Wy-45, 233 and other identified metabolites of the antidepressant venlafaxine. Drug Develop Res. 1991;23:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Preskorn SH. Pharmacotherapeutic profile of venlafaxine. Eur J Psychiat. 1997;12(Suppl 4):285S–294S. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)83307-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Richelson E, Nelson A. Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;230:94–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E. Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds. Psychopharmacology. 1994;114:559–565. doi: 10.1007/BF02244985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassan SM, Wainscott G, Turner P. A comparison of the effect of paroxetine and amitriptyline on the tyramine pressor response test. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1985;19:705–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1985.tb02700.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruffolo RR. Spare α adrenoceptors in the peripheral circulation: excitation-contraction coupling. Fed Proc. 1986;45:2341–2346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levenson J, Simon AC, Moyse D, Bouthier J, Safar ME. Peripheral hemodynamic effects of short-term nadolol administration in essential hypertension. Am Heart J. 1984;108:1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90604-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM, Boston PF, Langley RW. The human pharmacology of reboxetine. Human Psychopharmacol. 1998;13:S3–S12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levitt P, Moore RY. Origin and organization of brainstem catecholamine innervation in the rat. J Comparative Neurology. 1979;186:505–528. doi: 10.1002/cne.901860402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szabadi E, Bradshaw CM. Autonomic pharmacology of α2-adrenoceptors. J Psychopharmacol. 1996;10(Suppl 3):6–18. [Google Scholar]