Abstract

Aims

This analysis was performed to validate a previously developed population pharmacokinetic model for lamotrigine in order to establish a basis for dosage recommendations for children.

Methods

(a) The importance of the covariates in the final model was confirmed using the model validation dataset. Population and individual (Bayesian estimate) pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated using both the initial model, which included none of the covariates, and the final model. Accuracy and precision of parameter estimation and of concentration prediction were compared between the two models. (b) The performance in predicting the validation concentrations by the final model parameters obtained previously from the model development dataset was assessed. (c) The parameters of the final model were refined using a dataset combining both the development and validation data.

Results

Prediction performance of the final pharmacostatistical model was superior to that of the initial model. The results of the validation confirmed that concomitant antiepileptic drugs that increased or reduced lamotrigine clearance in adults had similar effects in children. The validation also verified the linear relationship between weight and clearance. The previously seen small sex effect on clearance was found statistically insignificant.

Conclusions

The current analysis confirmed the previous findings. To achieve the same concentrations, children receiving enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs without valproate require higher doses than those receiving valproate; and heavier children require higher doses.

Keywords: adjunctive therapy, children, lamotrigine, population pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Lamotrigine (Lamictal®) is a sodium channel blocker with established safety and efficacy as an antiepileptic drug (AED) for adults and children [1–15]. The pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine (LTG) in adults have been reviewed by Goa et al. [16]. The absolute bioavailability following oral administration is 98%. In plasma, LTG is approximately 55% bound to protein. The oral clearance (CL) and apparent volume of distribution (V) averaged 0.35–0.59 ml min−1 kg−1 and 0.9–1.3 l kg−1, respectively, in various studies. The mean plasma half-life ranged from 24 to 37 h. In humans, the drug is inactivated predominantly by glucuronic acid conjugation. Commonly used AEDs carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbitone and primidone induce the metabolism of LTG, and valproate (VPA) inhibits the metabolism of LTG.

Although most cases of epilepsy are diagnosed during childhood and adolescence, information on the pharmacokinetics of LTG in children is limited [17–19]. Conventional pharmacokinetic studies require extensive blood sampling, and are therefore difficult to conduct in children. Population pharmacokinetic analysis is an attractive approach as it uses fewer samples from each patient. Children with epilepsy represent a diverse population due to the wide range of demographics and complex concurrent therapies increases the potential for drug interactions [20]. Understanding the kinetics of LTG in children with different demographic characteristics or concomitant medication is important for effective dosing. The objective of the current analysis was to validate a previously developed paediatric population pharmacokinetic model in order to establish a basis for dosage recommendations in adjunctive therapies.

Methods

Model development

The model development has been reported elsewhere [21] and is summarized here. The population pharmacostatistical model was developed using nonlinear mixed-effect modelling (NONMEM) program [22] on 652 plasma LTG concentrations collected from 202 patients enrolled in three add-on phase III paediatric studies (Tables 1 and 2). Each patient received VPA and/or at least one AED that was known to induce LTG metabolism in adults (EI). A one-compartment open model with first-order absorption and first-order elimination [23–26] was characterized by CL, V and absorption rate constant (ka). Effects of concurrent AEDs, weight (WT), sex, age and race on CL and the effect of WT on V were evaluated. The statistical significance of α ≤ 0.05, assessed by the change in the minimum value of the objective function (MVOF), was the primary criterion for including any effect in the model.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Development data set (n = 202) | Validation data set (n = 148) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (male:female) | 114 : 88 | 82 : 66 |

| Age (median, 5th ∼ 95th percentile) (years) | 8.9, 3.4 ∼ 15 | 7.6, 2.6 ∼ 17 |

| Weight (median, 5th ∼ 95th percentile) (kg) | 27, 14 ∼ 56 | 26, 12 ∼ 71 |

| Single dose: Multiple dose | 0 : 202 | 39 : 79 |

| Receiving enzyme inducers without valproate | 99 | 86 |

| Receiving valproate without enzyme inducers | 58 | 39 |

| Receiving enzyme inducers and valproate | 45 | 23 |

Table 2.

Dosage regimen and sampling schedule during treatment phase.

| Protocol | Dataset | Patients | Dosage regimen | Sampling schedule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | validation | epilepsy (n = 19) | single 2 mg kg−1 dose | 6 samples up to 48 h post dose |

| 2 | validation | epilepsy (n = 20) | single 2 mg kg−1 dose | 6 samples up to 48 h post dose |

| 3 | validation | partial seizures(n = 64) | with enzyme inducing AEDs and without VPA week 1–2 2 mg kg−1 day−1 week 3–4 5 mg kg−1 day−1 week 5–6 10 mg kg−1 day−1 week 7–18 15 mg kg−1 day−1with VPA and without enzyme inducing AEDs week 1–2 0.5 mg kg−1 day−1 week 3–4 1 mg kg−1 day−1 week 5–6 2 mg kg−1 day−1 week 7–18 3 mg kg−1 day−1others week 1–2 0.5 mg kg−1 day−1 week 3–4 1 mg kg−1 day−1 week 5–6 2 mg kg−1 day−1 week 7–18 5 mg kg−1 day−1 | 1 sample each at end of weeks 6, 10, 14 and 18 |

| 4 | validation | Lennox–GastautSyndrome (n = 45) | 15 kg ≤ weight ≤ 25 kg with VPA week 1–2 5 mg od week 3–4 10 mg od week 5–6 25 mg od week 7–8 50 mg od week 9–16 50 mg od, or 100 mg od weight > 25 kg with VPA week 1–2 10 mg od week 3–4 25 mg od week 5–6 50 mg od week 7–8 100 mg od week 9–16 100 mg od, or 200 mg od weight ≤ 25 kg without VPA week 1–2 25 mg od week 3–4 25 mg bd week 5–6 50 mg bd week 7–8 100 mg bd week 9–16 100 mg bd, or 100 mg mane and 200 mg nocte weight > 25 kg without VPA week 1–2 25 mg bd week 3–4 50 mg bd week 5–6 100 mg bd week 7–8 100 mg mane and 200 mg nocte week 9–16 100 mg mane and 200 mg nocte, or 200 mg bd | 1 sample each at end of weeks 4 and 16 |

| 5 | development | epilepsy (n = 49) | with VPA week 1–4 0.5–1.5 mg kg−1 day−1 week 5–8 0.5–2.5 mg kg−1 day−1 week 9–48 1.25–3.5 mg kg−1 day−1without VPA week 1–4 1.5–5 mg kg−1 day−1 week 5–8 3–10 mg kg−1 day−1 week 9–48 4–15 mg kg−1 day−1 | 1 sample each at end of weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48 |

| 6 and 7 | development | epilepsy (n = 153) | with VPA week 1–2 0.5–1 mg kg−1 day−1 week 3–4 1–2 mg kg−1 day−1 week 5–48 1.5–3 mg kg−1 day−1without VPA week 1–2 2 mg kg−1 day−1 week 3–4 4–5 mg kg−1 day−1 week 5–48 6–10 mg kg−1 day−1 | 1 sample each at end of weeks 4, 12, 24, 36 and 48 |

The initial model did not include any patient covariate. In the final model, population mean CL and V were modelled as:

and

where, BAL = 1 for those receiving valproate in addition to at least one EI, and BAL = 0 otherwise; VPA = 1 for those receiving VPA in the absence of any EI and VPA = 0 otherwise; SEX = 0 for males and SEX = 1 for females.

The intersubject variabilities in CL, V and ka were modelled as follows:

where CLj, Vj and kaj were values of CL, V and ka, respectively, for the jth patient; kapop was the population mean ka; and η1j, η2j and η3j were patient-specific values of the random variables η1, η2 and η3 with means of zero and variances of ω12, ω22 and ω32, respectively.

The intrasubject residual in concentration was modelled as:

where Cobsij and Cpredij were, respectively, the observed and predicted ith concentrations in the jth patient; and εij was a random variable with a mean of zero and a variance of σ12. Model parameter estimates are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Parameter estimates of the population pharmacokinetic model.

| Development data | Validation data | Combined data | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial model | Final model | Initial model | Final model | Initial model | Final model | |||||||

| Parameter | estimate | s.e. | estimate | s.e. | estimate | s.e. | estimate | s.e. | estimate | s.e. | estimate | s.e. |

| MVOF | 1504 | 698.1 | 794.4 | 308 | 2322.5 | 1151 | ||||||

| Θ1 | 15.9 | 1.12 | 28.5 | 4.8 | 14.5 | 1.43 | 17.8 | 2.72 | 15.5 | 0.921 | 19.3 | 2.69 |

| Θ2 | 0.756 | 0.188 | 0.5 | 0.107 | 0.598 | 0.102 | ||||||

| Θ3 | −0.638 | 0.0294 | −0.667 | 0.0812 | −0.605 | 0.047 | ||||||

| Θ4 | −0.822 | 0.0107 | −0.771 | 0.0233 | −0.772 | 0.017 | ||||||

| Θ5 | −0.12 | 0.0511 | ||||||||||

| Θ6 | 32.5 | 29.5 | 1.03 | 0.802 | 39.8 | 7 | 1.99 | 0.144 | 42.7 | 4.56 | 2.12 | 0.142 |

| Θ7 | 0.1 | 0.128 | 0.113 | 0.0933 | 1.12 | 0.228 | 1.12 | 0.195 | 1.04 | 0.163 | 1.09 | 0.163 |

| ω12 | 0.968 | 0.098 | 0.125 | 0.02 | 0.936 | 0.187 | 0.351 | 0.083 | 0.994 | 0.104 | 0.259 | 0.045 |

| ω22 | 0.000002 | 0.00002 | 0.607 | 2.4 | 0.452 | 0.518 | 0.174 | 0.0583 | 0.651 | 0.611 | 0.26 | 0.085 |

| ω32 | 6.01 | 14.2 | 1.41 | 3.62 | 2.23 | 1.29 | 2.12 | 0.629 | 2.8 | 1.17 | 2.45 | 0.707 |

| σ12 | 0.0548 | 0.01 | 0.0648 | 0.008 | 0.0662 | 0.019 | 0.0541 | 0.009 | 0.0641 | 0.009 | 0.0583 | 0.006 |

Initial model: CL = Θ1; V = Θ6 Final model: CL = [Θ1+ Θ2 WT][1 + Θ3 BAL][1 + Θ4 VPA][1 + Θ5 SEX]; V = Θ6 WT Both models: ka = Θ7 The units for CL, V, ka and WT were ml min−1, l, h-1 and kg, respectively. ω2s and σ12were defined in text and were unitless.

Clinical protocols and patient characteristics

The model validation dataset contained a total of 508 concentrations collected from 148 patients (Table 1) enrolled in four studies, two single-dose pharmacokinetic studies [18, 19] and two efficacy/safety trials [13, 14] of placebo-controlled parallel design with LTG or placebo added to the existing AED therapy which was maintained unchanged during the trials (Table 2). The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In the efficacy/safety trials, daily doses were gradually increased over several weeks and the dosage regimens were dependent upon the concomitant AEDs. The majority of the efficacy/safety trial samples were collected later in the dosing intervals.

Sample analysis

Plasma samples collected from the pharmacokinetic studies were assayed using a high performance liquid chromatography method and the samples obtained from the efficacy/safety trials were analysed using an immunofluorometric assay. The two methods have been cross validated [27].

Dataset preparation

Dosing history, sampling time and patient covariates relevant to the model, i.e. WT, sex and concomitant AEDs, were obtained from clinical study case report forms. Concentrations that were [1] below the lower limit of quantification, [2] associated with conflicting dosing, sampling or covariate documentation, or [3] clearly associated with a lack of compliance as determined by tablet count when dosing history during the 4 weeks prior to sample collection was incomplete, were not included in the analysis.

Model validation

Overall strategy The model validation was performed in three sequential steps using the first-order estimation method in NONMEM [22]. The approach was similar to the one developed by Bruno et al. to validate a population pharmacokinetic model for docetaxel [28]. First, the importance of the covariates in the final model was confirmed using the model validation dataset. Second, the performance in predicting the validation concentrations by the final model parameters obtained with the model development dataset was assessed. Third, the parameters of the final model were refined using a dataset combining both the development and validation data.

Superiority of the final model over the initial model The accuracy and precision in parameter estimation and in concentration prediction were compared between the initial and final models. Population and individual parameters were estimated with each model using the validation dataset. Accuracy and precision in parameter estimation were assessed by bias and variability, respectively, defined as follows:

where Pj and Ppopj denoted the individual and population estimates, respectively, of the pharmacokinetic parameter P (CL or V) for the jth patient. The individual value was an empirical Bayesian estimate obtained on the basis of the population value and the observed concentrations in that individual, using the posthoc option during estimation. Lower mean bias or mean variability each indicated higher accuracy or precision.

Improvement from the initial model to the final model in the prediction of individual values of parameter P was defined as follows:

where Pj2 and Ppopj2 represented individual and population estimates of parameter P for the jth patients using the final model, and Pj1 and Ppopj1 were those using the initial model. Mean improvement was mathematically identical to the difference in mean variability between the initial and final models, and it represented the average advantage gained for each patient by using the final model for prediction.

To confirm the importance of including the covariates in the model, bias, variability and improvement were assessed for all patients, as well as the subpopulations characterized by the model. For CL, these subpopulations were patients receiving at least one EI and not VPA, patients receiving VPA and no EI, patients receiving VPA in addition to at least one EI, males, females and patients in each quartile of WT distribution. For V, the subpopulations were those in each quartile of WT. In addition, performance for CL and V estimation was assessed for patients in each quartile of the respective parameter.

Bias and variability in concentration prediction were evaluated according to:

where Cobsij and Cpredij were the observed and predicted ith concentration in the jth patient. Lower mean bias or mean variability suggested higher accuracy or precision in concentration prediction.

The improvement in concentration prediction using the final model as opposed to the initial model was calculated according to:

where Cpredij1 and Cpredij2 represented the ith concentration in the jth patients predicted using the initial and final model, respectively. As for parameter estimation, mean improvement in concentration prediction was mathematically identical to the difference in mean variability between the initial and final models and it represented the average advantage gained for each patient by using the final model.

Prediction power of the model parameters Plasma concentrations in the validation dataset were compared to those predicted using the final model parameters obtained from the model development dataset. Both accuracy and precision of such prediction were assessed for all concentrations, as well as for concentrations collected in the subpopulations defined by the model.

Refinement of the parameter values The validation data was combined with the development data to re-estimate the parameters of the final pharmacostatistical model.

Results

Superiority of the final model over the initial model

The parameters of both models estimated using the development, validation and combined datasets are presented in Table 3. With all datasets, MVOF (a statistic which approximates the −2 log likelihood for the data) was much lower for the final model than for the initial model. Consistently, values of most interpatient random variability terms were smaller in the final model.

Using the development dataset, V (Θ6), ka (Θ7), and their interpatient variabilities ω22 and ω32 in both models were poorly estimated, reflected by the large standard errors. Using the validation or combined dataset, all parameters in both models were well estimated except for ω22 and ω32 in the initial model. The effect of sex on CL (Θ5) was poorly estimated with the development dataset and became statistically insignificant with the validation dataset. This effect was subsequently removed from the model.

Estimation of CL

The individual value of CL determines the dosage requirement for the patient. Therefore the performance in CL prediction was compared between the two models using the validation dataset (Figure 1). When all patients were treated as one group, CL was estimated with much better accuracy and precision by the final model. Bias and variability averaged 22.8 and 43.6% for the final model, compared to 70.4 and 99.0% for the initial model. Prediction accuracy improved in 71% of the patients and the average improvement for each patient was 55.4%. Based on binomial distribution, the probability that improvement occurs in 71% of the patients under the null hypothesis, P = 50%, is 7.23 × 10−8. Prediction performance for CL was further evaluated in the patient groups defined by the covariate model. In all groups except those receiving both EI and VPA and those within the second quartile of CL distribution, for which mean bias was poorly estimated, both accuracy and precision were markedly better with the final model. Mean improvement in prediction ranged 17.8–144.7% and the prediction improved in 59–92% of all patients among these groups. Consistent with the improved precision by the final model, the intersubject variability in CL reduced from ω12 = 0.936 for the initial model to ω12 = 0.351 for the final model (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Performance in CL prediction by both initial and final models. Column heights represent mean. Error bars represent s.e. mean. □ Bias: initial model;  Bias: final model;

Bias: final model;  Variability: initial model;

Variability: initial model;  Variability: final model;

Variability: final model;  improvement;

improvement;  patients improved.

patients improved.

Estimation of V

When all patients were included, variability was smaller with the final model (11.9%) than with the initial model (18.5%), and bias was small with both models (Figure 2). Improvement in accuracy by using the final model averaged 6.5% and occurred in 61% of the patients. Based on binomial distribution, the probability that under the null hypothesis, P = 50%, improvement occurs in at least 61% of the patients is 5.29 × 10−3. Mean bias and mean improvement were poorly estimated in many of the groups. However, larger reductions in bias and variability and greater improvement appeared to occur in groups at the extremes of the WT and Bayesian V distributions. This observation supported the linear relationship between these variables. A large reduction in variability was observed from ω32 = 0.452 with the initial model to ω22 = 0.174 with the final model (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Performance in V prediction by both initial and final models. Column heights represent mean. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. □ Bias: initial model;  Bias: final model;

Bias: final model;  Variability: initial model;

Variability: initial model;  Variability: final model;

Variability: final model;  improvement;

improvement;  patients improved.

patients improved.

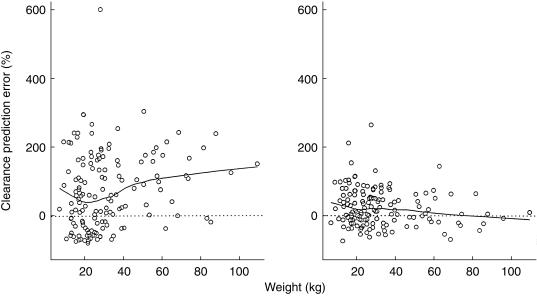

The results of the quantitative comparison of the estimation performance between the two models were supported by graphical examination of the data. The apparent correlation between CL prediction error and WT in the initial model (Figure 3) suggested that CL should be a function of WT. Such correlation disappeared in the final model when the effect of WT on CL became part of the model. Similarly, the large prediction errors for CL associated with the initial model in the three concomitant AED groups (Figure 4) were greatly reduced when the effects of these drugs on CL were taken into account in the final model (except for those receiving EI and VPA). The obvious correlation between V prediction error and WT in the initial model (Figure 5), which indicated that V was a function of WT, was removed almost completely when such function was incorporated into the final model.

Figure 3.

WT against CL prediction error by the initial (left) and final (right) models. Solid curve: locally weighted average.

Figure 4.

CL prediction error in patients receiving different concomitant AEDs. Left: initial model; right: final model; horizontal lines within boxes: medians; height of the boxes: differences between the third and the first quartiles (IQD). The whiskers extend to the extremes of the data or 1.5 IQD from the median, whichever is less. Data outside the whiskers are denoted by horizontal lines.

Figure 5.

WT against V prediction error. Left: initial model; right: final model. Solid curve: locally weighted average.

Prediction of concentrations

A direct comparison for concentration prediction bias between the models was not feasible due to the large standard error associated with bias estimates (Table 4). Nevertheless, a mean improvement of 18.3% per sample was achieved by the final model over the initial model. The estimation variability also decreased from 66.0% to 47.7%. Concentration prediction by both models is shown in Figure 6, where the data points are much closer to the line of identity in the case of the final model.

Table 4.

Plasma concentration prediction by initial and final models (n = 508).

| Bias (%) | Variability (%) | Improvement (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Mean | s.e. | Mean | s.e. | Mean | s.e. |

| Initial | 0.9 | 3.9 | 66.0 | 2.5 | 18.3 | 3.1 |

| Final | 8.3 | 3.1 | 47.7 | 2.3 | ||

Figure 6.

Concentration prediction by the initial (left) and final (right) models. Dotted line: line of identity.

In summary, parameter estimation and concentration prediction using the validation dataset confirmed the superiority of the final pharmacostatistical model to the initial model.

Prediction power of the model parameters

Plasma concentrations in the validation dataset were predicted using the final model parameters obtained from the development dataset (Table 5). The concentrations were under-estimated by an average of 65.5%. The under-estimation of the concentrations occurred in all subgroups to a similar extent of 57.4% to 74.9%. The estimation variability was large and similar (82.0% to 97.5%) among the subgroups. The large bias and low precision suggested that although the structure of the final model was tested to be superior to that of the initial model, the final model parameters need to be refined, perhaps using a combined dataset.

Table 5.

Prediction of validation concentrations by final model parameters derived from development dataset.

| Bias (%) | Variability (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient sub-population | n | Mean | s.e. | Mean | s.e. |

| All | 508 | 65.5 | 6.4 | 90.6 | 5.7 |

| EI + VPA | 74 | 72.7 | 20.3 | 7.5 | 18.9 |

| EI | 304 | 67.1 | 8.0 | 92.6 | 7.1 |

| VPA | 130 | 57.4 | 11.9 | 82.0 | 10.8 |

| Male | 273 | 64.9 | 7.7 | 86.6 | 6.9 |

| Female | 235 | 66.1 | 10.5 | 95.2 | 9.5 |

| WT (kg) < 18.2 | 164 | 61.7 | 11.0 | 91.8 | 9.7 |

| 18.2 < WT (kg) < 25.75 | 136 | 68.0 | 13.2 | 93.0 | 12.0 |

| 25.75 < WT (kg) < 36.75 | 104 | 58.7 | 14.0 | 86.0 | 12.6 |

| WT (kg) > 36.75 | 104 | 74.9 | 13.4 | 90.1 | 12.5 |

Refinement of the parameter values

When both models were fitted to the combined dataset, the final model again showed lower MVOF and random variabilities (Table 3). All parameters of the final model were estimated with good precision. Parameter values were similar to those obtained using the validation dataset alone. The final models for population CL and v were:

and

where the units for WT, CLpop and Vpop were kg, ml min−1 and l, respectively.

Discussion

Using the conventional two-stage method to study the pharmacokinetics of a drug in a population with diverse characteristics requires frequent sampling from a large number of patients. In paediatrics, the blood volume requirement presents additional challenge. The population pharmacostatistic approach has received increasing attention in recent years [29, 30]. The main advantage of this approach is that it does not require as intense sampling as the two-stage method. The population approach relies on observations sparsely collected in a diverse patient population to characterize the kinetics of the drug in the subpopulations of interest. The paediatric indication of adjunctive LTG provided an ideal situation for the application of this approach.

A number of validation strategies including data splitting [31], cross-validation [32] and bootstrapping [33] have been proposed as alternatives when a separate dataset is not available for validation purposes. These techniques are useful to improve the precision in parameter estimation but are inadequate for validating the findings, as the distribution of the validation data relies heavily on the original data. The data used in the current validation were completely independent of the data used to develop the model.

The previously developed model suggested that CL of LTG was a function of concomitant AEDs, WT and sex. Fitting both the initial simple model and the final pharmacostatistical model to the validation dataset confirmed the superiority of the final model which showed better accuracy and precision in CL estimation and concentration prediction. The validation confirmed the effects of the AEDs (carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, primidone and valproate) and WT on CL (Figure 7). To achieve similar concentrations, patients receiving EI without VPA require higher doses. Further, heavier children need lower WT-normalized doses since CL was not directly proportional to WT.

Figure 7.

CL as a function of WT and concurrent AED therapy. Symbols: Bayesian estimates of CL (circles: EI; triangles: VPA; pluses: EI and VPA); dotted lines: locally weighted average; solid lines: model predictions (top: EI; middle: EI and VPA; bottom: VPA).

The small but significant (12%) sex effect on CL that had been observed during model development was found to be insignificant. This illustrated a problem associated with data-driven modelling exercises. Although such approaches are very useful in exploratory analyses, the outcomes tend to be influenced by the nature of the often retrospectively collected data and can also be model dependent. It was concluded from these results that the same dose could be used in both males and females.

The validation data were collected in two single-dose kinetic studies and two multiple-dose phase III trials; while the model development data were obtained from three phase III trials. It has been suggested that CL in adults receiving LTG monotherapy increases modestly after chronic dosing [16]. Therefore patients in the development dataset might have higher mean CL. This may help explain the under-prediction of the validation concentrations by the parameters derived from the development dataset.

A previous analysis in patients receiving monotherapy showed that CL of LTG was not significantly influenced by WT [26]. The analysis was conducted in a group of adults weighing 40.5–106.5 kg, a range less than three fold. The WT range in the validation dataset for the current analysis was 6.6–108.6 kg, more than 15 folds. The WT range was much wider in the latter case and a significant WT effect was therefore more likely to be detected. Both analyses concluded a lack of gender effect on CL [26].

The directly proportional relationship between V and WT was also confirmed (Figure 8). Weight did not show a significant effect on V in the adult analysis mentioned above [26], probably due to the relatively narrow WT range.

Figure 8.

V as a function of WT. Circles: Bayesian estimates of V; dotted line: locally weighted average; solid line: model predictions.

Initiation of LTG therapy requires a slow dose-escalation. The results of the current analysis were used to recommend convenient escalation schedules for children to generate average plasma concentrations close to and not higher than those in adults. Children receiving a concomitant AED regimen containing an EI and not VPA are recommended to take lamotrigine at 0.6 mg kg−1 day−1 for the first 2 weeks of the therapy and 1.2 mg kg−1 day−1 for the next 2 weeks. Daily dose can then be increased by 1.2 mg kg−1 day−1 every 1 to 2 weeks to achieve maintenance. Children on an AED regimen containing VPA are recommended to take 0.15 mg kg−1 day−1 for the first 2 weeks and 0.3 mg kg−1 day−1 for the next 2 weeks. Daily dose can subsequently be increased by 0.3 mg kg−1 day−1 every 1 to 2 weeks to reach a maintenance dose.

As the pharmacostatistical model only described the kinetics of LTG in children receiving common AEDs known to affect the drug's CL in adults (carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbitone, primidone or VPA), the pharmacokinetics of LTG in children in the absence of these drugs remain to be studied.

The current analysis confirmed that oral clearance of lamotrigine in children was a function of weight and concurrent antiepileptic therapy. To achieve the same concentrations, children receiving enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs without valproate require higher doses than those receiving valproate; and heavier children require higher doses.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Vincent Barnett and Cameron Huffman for their assistance in database preparation and Dr Keith Muir for his encouragement and insightful comments.

References

- 1.Leach MJ, Marden CM, Miller AA. Pharmacological studies on lamotrigine, a novel potential antiepileptic drug II. Neurochemical studies on the mechanism of action. Epilepsia. 1986;27:490–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb03573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsuo F, Bergen D, Faught E, et al. Placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of lamotrigine in patients with partial seizures. Neurology. 1993;43:2284–2291. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Messenheimer J, Ramsay RE, Willmore LJ, et al. Lamotrigine therapy for partial seizures: a multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial. Epilepsia. 1994;35:113–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1994.tb02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schachter SC, Leppik IE, Matsuo F, et al. Lamotrigine: a six-month, placebo-controlled, safety and tolerance study. J Epilepsy. 1995;8:201–209. 10.1016/0896-6974(95)00034-b. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loiseau P, Yuen AWC, Duche B, Menager T, Arne-Bes MC. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover add-on trial of lamotrigine in patients with treatment-resistant partial seizures. Epilepsy Res. 1990;7:136–145. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(90)90099-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith D, Baker G, Davies G, Dewey M, Chadwick DW. Outcomes of add-on treatment with lamotrigine in partial seizures. Epilepsia. 1993;34:312–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schapel GJ, Beran RG, Vajda FJE, et al. Double-blind, placebo controlled, crossover study of lamotrigine in treatment of resistant partial seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1993;56:448–453. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.5.448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jawad S, Richens A, Goodwin G, Yuen WC. Controlled trial of lamotrigine (Lamictal) for refractory partial seizures. Epilepsia. 1989;30:356–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1989.tb05309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilliam F, Vazquez B, Sackellares JC, et al. An active-control trial of lamotrigine monotherapy for partial seizures. Neurology. 1998;51:1018–1025. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodie MJ, Richens A, Yuen AW. Double-blind comparison of lamotrigine and carbamazepine in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Lancet. 1995;345:476–479. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner TJ, Yuen AWC. Comparison of lamotrigine (Lamictal) and phenytoin monotherapy in newly diagnosed epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1994;35:61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reunanen M, Dam M, Yuen AWC. A randomized open multicenter comparative trial of lamotrigine and carbamazepine as monotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed or recurrent epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1996;23:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00085-2. 10.1016/0920-1211(95)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graf WD, Pellock JM, Duchowny M, Womble G, Manasco P. Lamotrigine is effective for add-on treatment of partial seizures in children and adolescents. Epilepsia. 1997;38:193. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motte J, Trevathan E, Arvidsson JF, Barrera MN, Mullens EL, Manasco P. Lamotrigine for generalized seizures associated with the Lennox–Gastaut syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1807–1812. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712183372504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank LM, Casale EJ, Womble G, Manasco P. Lamictal is effective for the treatment of typical absence seizures in children and adolescents. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:489. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goa KL, Ross SR, Chrisp P. Lamotrigine: a review of its pharmacological properties and clinical efficacy in epilepsy. Drugs. 1993;46:1–25. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199346010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eriksson AS, Hoppu K, Nergardh A, Boreaus L. Pharmacokinetic interactions between lamotrigine and other antiepileptic drugs in children with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1996;37:769–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vauzelle-Kervroedan F, Rey E, Cieuta C, et al. Influence of concurrent antiepileptic medication on the pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine as add-on therapy in epileptic children. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;41:325–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.31610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallas S. Add-on open trial of lamotrigine in resistant childhood seizures. Brain Dev. 1990;12:1734. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riva R, Albani F, Contin M, Baruzzi A. Pharmacokinetic interactions between antiepileptic drugs. Clin Pharmacokin. 1996;31:470–493. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199631060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen C, Grasela TH, Phillips L, Friedler-Kelly JB, Womble G, Risner ME, Yau MK. Population Pharmacokinetics of Add-On Lamotrigine in Pediatric Patients. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:508. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beal SL, Boeckman AL, Sheiner LB. San Francisco: University of California at San Francisco; 1992. NONMEM. User′ s Guide (Double Precision, Version 4.0, Level 2.0) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jawad S, Yuen WC, Peck AW, Hamilton MJ, Oxley JR, Richens A. Lamotrigine: single-dose pharmacokinetics and initial 1 week experience in refractory epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1987;1:194–201. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(87)90041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuen WC, Peck AW. Lamotrigine pharmacokinetics: oral and i.v. infusion in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;26:242P. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peck AW. Clinical pharmacology of lamotrigine. Epilepsia. 1991;32:S9–S12. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1991.tb05883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hussein Z, Posner J. Population pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine monotherapy in patients with epilepsy: retrospective analysis of routine monitoring data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:457–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sailstad JM, Findlay JWA. Immunofluorometric assay for lamotrigine (Lamictal) in human plasma. Ther Drug Monit. 1991;13:433–442. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199109000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruno R, Vivier N, Vergniol JC, De Phillips SL, Montay G, Sheiner LB. A population pharmacokinetic model for docetaxel (Taxotere): model building and validation. J Pharmacokin Biopharm. 1996;24:153–172. doi: 10.1007/BF02353487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peck CC, Barr WH, Benet LZ, et al. Opportunities for integration of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and toxicokinetics in rational drug development. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;51:465–473. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aarons L, Balant LP, Mentre F, et al. Practical experience and issues in designing and performing population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;49:251–254. doi: 10.1007/BF00226323. 10.1007/s002280050014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roecker EB. Prediction error and its estimation for subset-selected models. Technometrics. 1991;33:459–468. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Efron B. Estimating the error rate of a prediction rule: improvement on cross-validation. J Am Stat Assoc. 1983;78:316–331. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ette EI. Population model stability and performance. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37:486–495. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1997.tb04326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]