Abstract

Aims

Propionyl-l-carnitine (PLC) is an endogenous compound which, along with l-carnitine (LC) and acetyl-l-carnitine (ALC), forms a component of the endogenous carnitine pool in humans and most, if not all, animal species. PLC is currently under investigation for the treatment of peripheral artery disease, and the present study was conducted to assess the pharmacokinetics of intravenous propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride.

Methods

This was a placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel group, dose-escalating study in which 24 healthy males were divided into four groups of six. Four subjects from each group received propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride and two received placebo. The doses (1 g, 2 g, 4 g and 8 g) were administered as a constant rate infusion over 2 h and blood and urine were collected for 24 h from the start of the infusion. PLC, ALC and LC in plasma and urine were quantified by h.p.l.c.

Results

All 24 subjects successfully completed the study and the infusions were well tolerated. In addition to the expected increase in PLC levels, the plasma concentrations and urinary excretion of LC and ALC also increased above baseline values following intravenous propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride administration. At a dose of 1 g, PLC was found to have a mean (± s.d.) half-life of 1.09 ± 0.15 h, a clearance of 11.6 ± 0.24 l h−1 and a volume of distribution of 18.3 ± 2.4 l. None of these parameters changed with dose. In placebo-treated subjects, endogenous PLC, LC and ALC underwent extensive renal tubular reabsorption, as indicated by renal excretory clearance to GFR ratios of less than 0.1. The renal-excretory clearance of PLC, which was 0.33 ± 0.38 l h−1 under baseline condition, increased (P < 0.001) from 1.98 ± 0.59 l h−1 at a dose of 1 g to 5.55 ± 1.50 l h−1 at a dose of 8 g (95% confidence interval for the difference was 2.18,4.97). As a consequence, the percent of the dose excreted unchanged in urine increased (P < 0.001) from 18.1 ± 5.5% (1 g) to 50.3 ± 13.3% (8 g). The renal-excretory clearance of LC and ALC also increased substantially after PLC administration and there was evidence for renal metabolism of PLC to LC and ALC.

Conclusions

Intravenous administration of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride caused significant increases in the renal excretory clearances of PLC, LC and ALC, due to saturation of the renal tubular reabsorption process–as a consequence there was a substantial increase with dose in the fraction excreted unchanged in urine. Despite the marked increase in the renal clearance of PLC, total clearance remained unchanged, suggesting a compensatory reduction in the clearance of the compound by non excretory routes.

Keywords: acetyl-l-carnitine, l-carnitine, nonlinear pharmacokinetics, propionyl-l-carnitine, renal clearance, renal metabolism, tubular reabsorption

Introduction

Propionyl-l-carnitine (PLC) is an endogenous compound which has therapeutic potential for the treatment of various cardiovascular disorders [1–3]. As an ester of l-carnitine (LC), its normal physiological role appears to be linked with the oxidation of fatty acids. Thus, LC is vital for the transport of fatty acids across the mitochondrial membrane for oxidation and energy production [4–6]. There is very little information in the literature regarding the pharmacokinetics of PLC in humans [7]. However, preclinical studies with PLC indicate that it undergoes extensive metabolism to LC [8–10], and since deacylation of carnitine esters occurs primarily within mitochondria [4], it follows that most tissues and organs of the body are likely to be involved in PLC metabolism. The renal handling of PLC involves extensive reabsorption via carrier systems that are also responsible, at least in part, for the reabsorption of LC and other short-chain carnitine esters such as acetyl-l-carnitine (ALC) [10, 11]. For all three of these carnitine analogues, renal clearance in the isolated perfused rat kidney increases once perfusate concentrations exceed normal endogenous plasma concentrations, a consequence of saturation of transport systems involved in their tubular reabsorption [10, 11]. Similarly, the renal clearance of LC in humans increases once the plasma concentrations exceed a threshold value [12–15].

In this study, the effect of PLC administration on the total and renal clearance of the parent compound, and the renal clearances of LC and ALC, was investigated. Studies in the perfused rat kidney indicate that the kidney is involved in the metabolism of PLC to LC and ALC [10]. Therefore, when considering the pharmacokinetics of PLC, a distinction must be made between the contribution of renal metabolism and renal excretion to the total renal clearance of the compound [10]. For instance, renal clearance estimated in the traditional manner, as urinary excretion rate divided by plasma concentration, is more appropriately referred to as ‘renal-excretory clearance’, and what is conventionally referred to as nonrenal clearance (estimated as the difference between total clearance and renal-excretory clearance) is better referred to as ‘nonrenal-excretory clearance’.

Methods

Study design

This was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, ascending-dose study in healthy subjects. Twenty-four males were recruited into four groups of six. In each group, four subjects received propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride and two subjects received placebo. One group was assigned for each of the four dose levels, ascending from the lowest to the highest. Progression to each dose level occurred only after the clinical evaluation of the tolerability of the previous dose. Propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride was administered as a constant rate intravenous infusion, into a peripheral arm vein, over 2 h. The doses administered were 1, 2, 4 and 8 g.

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised, and in accordance with GCP and GLP guidelines. The final protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee and subjects provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Subjects

Twenty-four healthy males, between 18 and 50 years of age and within 10% of the desired weight for height were recruited for the study. Subjects were required to have no clinically significant medical history and have acceptable screening laboratory results. Screening occurred within 2 weeks of the start of the study, and all subjects underwent a physical examination which included an ECG recording. Screening blood tests included haematology, serology, serum chemistry, and urinalysis.

Drug administration and sample collection

Each subject received one single dose of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride, or placebo, in accordance with a randomization code. Propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride was provided as 500 mg freeze-dried ampoules with solvent (Sigma Tau spa, Pomezia, Italy). Placebo ampoules were also provided (Sigma Tau spa). A pharmacist prepared the infusion solutions, on the day of administration, by adding the required volume of reconstituted propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride (or placebo) to an infusion bag containing 0.9% sodium chloride, such that the final bag volume was exactly 250 ml.

Following an overnight fast, two cannulae were inserted into forearm veins of each volunteer (one on each arm). After collection of a predose blood sample (3 ml), each subject was instructed to empty his bladder. The infusion of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride was started and allowed to run for 2 h. The infusions were performed with IMED Gemini volumetric pumps (IMED Corporation, San Diego, USA). In delivering the required amount of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride (or placebo) the total target volume infused was 166.6 (at 83.3 ml h−1) or 200 ml (100 ml h−1).

Blood samples (3 ml) were collected from an indwelling cannula immediately prior to the start of the infusion (0 h sample), during the infusion (5, 10, 15 and 30 min and 1, 1.5 and 2 h) and after stopping the infusion (5, 10, 15, and 30 min, and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 22 h). Hence, the final blood sample was collected 24 h after the start of the infusion. Blood was collected into labelled lithium-heparinized tubes. After immediate centrifugation, plasma was separated and placed into suitably labelled polypropylene tubes and stored at −20 °C. Urine collections were conducted over the following time intervals after commencing the PLC infusion: 0–2, 2–4, 4–8, 8–12 and 12–24 h. After mixing all voids within an interval, and measuring the total volume voided during an interval, a 10 ml aliquot was taken and stored at −20 °C.

Analytical methods

PLC, LC and ALC in plasma and urine were analysed using a validated h.p.l.c. method involving solid phase purification, derivatization and fluorescence detection on a reversed-phase h.p.l.c. system [16]. The calibration ranges for PLC, LC and ALC in plasma were 0.25–160 nmol ml−1, 2.5–80 nmol ml−1 and 0.5–32 nmol ml−1, respectively. For urine, the calibration ranges were 2.5–320, 2.5–320 and 1–128 nmol ml−1, for PLC, LC and ALC, respectively. For plasma, calibration curves were prepared using human plasma that had been dialysed to remove endogenous PLC, LC and ALC [16]. The lowest point on each calibration curve defined the limit of quantification (LOQ) and samples with a measured concentration less than LOQ were assigned a concentration value of zero. The accuracy and precision of the method, as assessed during the analysis of study samples, were within 20%.

Pharmacokinetic methods

For PLC, LC and ALC, the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the corresponding time of occurrence (tmax) were obtained directly from the individual plasma concentration data. For all three carnitine analogues the linear trapezoidal rule was used to estimate the area under the plasma concentration vs time curve from zero to 24 h (AUC(0,24h)). For PLC, a baseline corrected area under the curve (AUC(bc)) was estimated by subtracting the predose plasma concentration from all post dose concentrations prior to the trapezoidal calculation. The half-life (t½) of PLC was calculated as 0.693/λz, where λz (the terminal rate constant) was determined by linear regression of log-transformed plasma concentration vs time data for the terminal portion of the profile (after stopping the infusion and prior to attainment of baseline). For LC and ALC, half-life estimates could not be obtained because of variability once plasma concentrations returned to within 50% of the baseline value. The total plasma clearance of PLC (CL) was taken to be Dose/AUC(bc) The volume of distribution of PLC (V) was calculated as CL/λz. For subjects who received placebo, the time-averaged plasma concentrations (Cav) of PLC, LC and ALC were calculated as AUC(0,24h) divided by the time interval (24 h).

For each analyte, the cumulative amount excreted in urine between zero and 24 h (AE(0,24)) was calculated by summing the corresponding amounts excreted during each collection interval, and expressed as a percent of the administered dose. Renal excretory clearance values during individual urine collection intervals () were estimated as AEti/AUCti, where ti represents a particular time interval. The time-averaged renal excretory clearance over 24 h () was calculated for each analyte as AE(0,24h)/AUC(0,24h).

Creatinine clearance (CLCR), for estimation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR), was calculated from serum creatinine using the following formula,

Statistical methods

Data are presented as arithmetic mean and standard deviation (s.d.). One-way analysis of variance (anova) was used to test for dose-related differences for all pharmacokinetic parameters and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the differences relative to the parameter determined for the 1 g dose. For all statistical tests, a P value less than 0.05 was taken to represent statistical significance.

Results

All subjects enrolled in this study proceeded to completion and the tolerability of intravenous propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride was excellent. In subjects who received placebo, the Cav values for PLC, LC and ALC were 1.28 ± 0.63, 40.2 ± 8.8 and 2.95 ± 1.36 nmol ml−1, respectively.

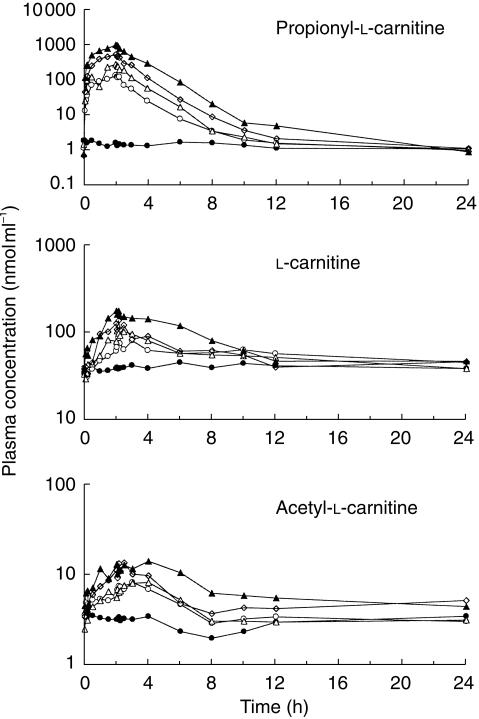

Mean (± s.d.) plasma PLC, LC and ALC concentration vs time profiles for all subjects are given in Figure 1. At each dose level, the plasma concentrations of LC and ALC increased during the infusion. Once the infusion had ceased, the plasma concentrations of PLC decreased rapidly, returning to near-baseline levels well within 12 h, whereas the plasma concentrations of LC and ALC decreased more gradually.

Figure 1.

Mean plasma concentration vs time profiles for PLC, LC and ALC in healthy male subjects treated with placebo (filled circles) or propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride at dose levels of 1g (open circles), 2g (open triangles), 4g (open diamonds) and 8g (filled triangles). At each dose level, propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride was administered as a constant rate intravenous infusion over 2 h in four subjects.

The Cmax, tmax and AUC(0,24h) data for all three analytes are summarized in Table 1. It is notable that for the highest dose of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride (8 g) the peak plasma concentrations for PLC was about 480 times higher than the peak concentration in placebo-treated subjects. The Cmax values for LC and ALC were 3-to 4-fold higher, at the 8 g dose of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride, than those obtained in placebo-treated subjects. At a dose of 1 g, the mean t½ of PLC was 1.09 h, clearance was 11.6 l h−1 and volume of distribution was 18.3 l (Table 2). None of these parameters tended to change as a function of dose.

Table 1.

Cmax, tmax and AUC(0,24h) data for PLC, LC and ALC after the administration of an intravenous infusion, over 2 h, of placebo solution (n = 8) or propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride at four dose levels (1g, 2g, 4g and 8g; n = 4 at each dose level).

| Analyte | Parameter | Placebo | 1g PLC | 2g PLC | 4g PLC | 8g PLC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLC | Cmax (nmol ml−1) | 2.2 ± 1.9 | 143 ± 14 | 288 ± 23 | 578 ± 110 | 1049 ± 196 |

| tmax (h) | - | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.1– | 2.1 ± 0.1 | |

| AUC(0,24 h) (nmol ml−1 h) | 31 ± 15 | 367 ± 8 | 767 ± 53 | 1475 ± 345 | 2934 ± 657 | |

| LC | Cmax (nmol ml−1) | 54 ± 14 | 95 ± 15 | 130 ± 33 | 151 ± 33 | 188 ± 32 |

| tmax (h) | – | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.36 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | |

| AUC(0,24 h) (nmol ml−1 h) | 965 ± 21 | 1315 ± 194 | 1300 ± 203 | 1346 ± 259 | 1767 ± 299 | |

| ALC | Cmax (nmol ml−1) | 4.8 ± 2.1 | 9.4 ± 2.8 | 9.3 ± 1.6 | 14.7 ± 4.5 | 16.4 ± 2.3 |

| tmax (h) | – | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | |

| AUC(0,24 h) (nmol ml−1 h) | 71 ± 33 | 95 ± 19 | 97 ± 13 | 132 ± 21 | 167 ± 47 |

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters (CL, V and t½) for PLC after an intravenous infusion, over 2 h, of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride at four dose levels levels (1g, 2g, 4g and 8g; n = 4 at each dose level). The table also presents the 95% confidence intervals for the differences between the mean values (comparisons with 1g dose only).

| Dose of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1g | 2g | 4g | 8g | anova | |

| Clearance (l h−1) | 11.6 ± 0.24 | 10.8 ± 0.75 (−4.0, 2.4) | 11.3 ± 2.7 (−3.5, 2.9) | 11.3 ± 3.0 (−3.5, 2.9) | P = 0.95 |

| (−4.0, 2.4) | (−3.5, 2.9) | (−3.5, 2.9) | |||

| Volume of distribution (l) | 18.3 ± 2.4 | 17.5 ± 1.4 | 17.4 ± 4.4 | 17.4 ± 4.9 | P = 0.98 |

| (−6.4, 4.7) | (−6.4, 4.6) | (−6.4, 4.6) | |||

| Half-life (h) | 1.09 ± 0.15 | 1.12 ± 0.07 | 1.07 ± 0.05 | 1.07 ± 0.10 | P = 0.85 |

| (−0.13, 0.18) | (−0.18, 0.13) | (−0.18, 0.13) | |||

For placebo-treated subjects, the 24 h urinary excretion of PLC, LC and ALC was 10 ± 12, 117 ± 122 and 29 ± 23 µmol, respectively. The excretion of all three compounds in placebo-treated subjects was low relative to that occurring in subjects dosed with propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride. For this reason, the urinary excretion data obtained after drug administration can be used to assess the metabolic fate of the compound. The results, presented in Table 3, show that after a 1 g dose of the drug, 59.4% can be accounted for as urinary PLC, LC and ALC, with LC being the predominant species (37.3%), and PLC accounting for 18.1% of the dose. In contrast, at the highest dose the dominant species in urine was PLC, accounting for 50.3% of the dose. The increase with dose in the percentage of the dose excreted in urine was highly significant (P < 0.001) and the 95% CI for the difference between the mean values after the 1 g and 8 g dose was 17.4,46.3% (Table 3).

Table 3.

Urinary excretion data for PLC, LC and ALC in healthy male subjects treated with placebo solution (n = 8) or propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride (1g, 2g, 4g and 8g; n = 4 at each dose level). Values are expressed as percentage of the dose recovered in urine during the 24 h after the start of the infusion. The table also presents the 95% confidence intervals for the differences between the mean values (comparisons with 1g dose only).

| Analyte | 1g PLC (n = 4) | 2g PLC (n = 4) | 4g PLC (n = 4) | 8g PLC (n = 4) | anova |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLC | 18.1 ± 5.5 | 13.6 ± 6.2 | 29.5 ± 10.3 | 50.3 ± 13.3 | P < 0.001 |

| (−19.3, 9.6) | (−3.3, 25.5) | (17.4, 46.3) | |||

| LC | 37.3 ± 15.5 | 30.3 ± 5.9 | 29.8 ± 6.6 | 26.4 ± 1.4 | P = 0.4 |

| (−20.8, 6.8) | (−21.3, 6.3) | (−24.7, 2.9) | |||

| ALC | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | P = 0.1 |

| (−2.9, 0.3) | (−2.5, 0.6) | (−3.6, −0.4) | |||

| Sum | 59.4 ± 21.2 | 46.3 ± 10.9 | 62.1 ± 17.5 | 78.4 ± 12.3 | P = 0.1 |

| (−37.8, 11.5) | (−22.0, 27.4) | (−5.7, 43.7) |

Under baseline conditions in placebo-treated subjects, the time-averaged renal-excretory clearance of PLC (0.32 ± 0.38 l h−1) was substantially less than the estimated creatinine clearance value in this group (6.08 ± 1.03 l h−1), indicating extensive tubular reabsorption (PLC is not bound to plasma proteins). Table 4 presents the mean (± s.d.) time-averaged (0–24 h) renal-excretory clearance values (CLR,ave) for each analyte after drug administration. For PLC, data are also provided on the differences between total clearance and time-averaged renal-excretory clearance (referred to as ‘nonrenal-excretory clearance’ or CLNR). Compared with placebo-treated subjects, the renal-excretory clearance of PLC was more than 6-fold higher after the 1 g dose (1.98 ± 0.59 l h−1). The renal excretory clearance values also increased significantly with dose (P < 0.001), reaching a mean value of 5.55 ± 1.50 l h−1 (8 g). In contrast, the nonrenal-excretory clearance of PLC was found to decrease significantly as the dose increased (P < 0.05). The net effect of the increase in renal-excretory clearance and the decrease in nonrenal-excretory clearance (Table 4) was that total clearance was unaffected by dose (Table 2).

Table 4.

Time-averaged renal-excretory clearance values (CLRave) for PLC, LC and ALC, nonrenal-excretory clearance values for PLC (CLNR) in subjects who received an intravenous infusion, over 2 h, of placebo (n = 8) or PLC (1g, 2g, 4g and 8g; n = 4 at each dose level). 95% CI for differences from 1 g dose in parentheses.

| Dose | PLC CLRav (l h−1) | CLNR (l h−1) | LC CLRav (l h−1) | ALC CLRav (l h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1g | 1.98 ± 0.59 | 9.62 ± 0.65 | 1.11 ± 0.34 | 1.51 ± 0.36 |

| 2g | 1.37 ± 0.57 | 9.41 ± 1.05 | 1.82 ± 0.23 | 1.92 ± 0.47 |

| (−2.00, 0.79) | (−3.47, 3.05) | (0.04, 1.39) | (−1.15, 1.97) | |

| 4g | 3.11 ± 0.61 | 8.18 ± 3.09 | 3.49 ± 0.40 | 3.27 ± 1.27 |

| (−0.28, 2.51) | (−4.70, 1.81) | (1.71, 3.06) | (0.20, 3.32) | |

| 8g | 5.55 ± 1.50 | 5.78 ± 2.60 | 4.80 ± 0.66 | 3.47 ± 1.46 |

| (2.18, 4.97) | (−7.11, −0.60) | (3.02, 4.36) | (0.40, 3.52) | |

| anova | P < 0.001 | P < 0.05 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.05 |

In placebo-treated subjects, the CLR,av values for LC (0.13 ± 0.14 l h−1) and ALC (0.51 ± 0.57 l h−1) were substantially less than creatinine clearance (6.08 ± 1.03 l h−1), signifying extensive tubular reabsorption. Again, the CLR,av values were found to be significantly higher (P < 0.05) in subjects who received propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride, and there was a significant increase in this parameter for both compounds as the dose of the compound increased (Table 4).

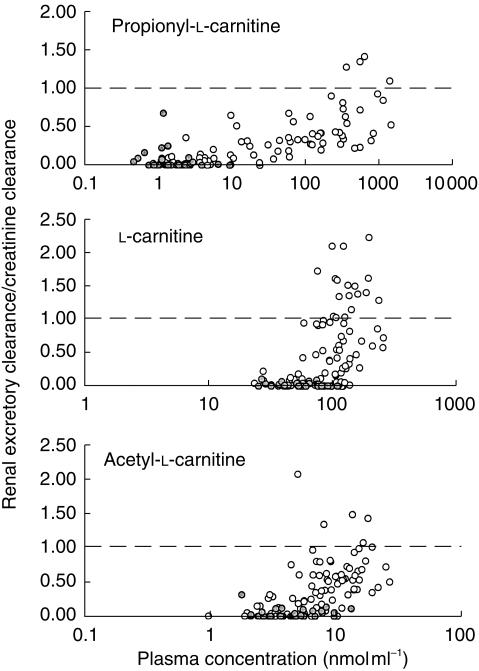

Figure 2 provides values for all three analytes plotted against the average plasma concentration of the analyte during the observation interval. Placebo-and propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride-treated subjects are identified within these plots. For PLC, the values increase once the plasma concentration of the compound exceeds 5–10 nmol ml−1. The ratio for LC and ALC also increase as a function of plasma concentration, but the ratio for these two compounds increases over a much narrower plasma concentration range than for PLC. Also, particularly for LC, the /CLCR values exceed unity in many cases (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between the ratio of renal-excretory clearance (during a urine sampling interval) to creatinine clearance and the average plasma concentration (during the same interval) for PLC, LC and ALC in subjects who received an intravenous infusion, over 2 h, of placebo or propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride at four dose levels (1g, 2g, 4g, 8g; n = 4 at each dose level). The data from the placebo-treated subjects is shown as shade-filled circles.

Discussion

PLC, LC and ALC are endogenous compounds that form components of the total carnitine pool. LC is the dominant species in plasma and more than 90% of the total body store of carnitine resides within skeletal muscle [16]. In the present study, the plasma concentrations of endogenous PLC, LC and ALC in placebo-treated subjects averaged 1.28, 40.2 and 2.95 nmol ml−1, respectively, over the 24 h period of observation. These values are similar to previously published data on the endogenous plasma levels of these compounds [16]. The amounts of LC and ALC recovered in urine over a 24 h period in placebo-treated subjects (117 and 29 µmol, respectively) are also similar to previous estimates for LC and ALC in healthy volunteers [13–18]. For PLC, no data on urinary excretion kinetics have been published previously.

The pivotal pharmacokinetic findings from this study can be summarized as follows: intravenous PLC has a short elimination half-life (1 h), a small volume of distribution (18 l) and a clearance of about 11 l h−1; the renal clearance of PLC (and LC and ALC) increases as the intravenous dose of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride is increased; and, based on urinary excretion data, LC is a major metabolite of intravenously administered propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride. The results of the study also provide an insight into the renal handling of these endogenous compounds and the consequences of a significant exogenous load.

Under baseline conditions, the time-averaged renal excretory clearance of PLC was 0.32 l h−1, or 5.3 ml min−1. The corresponding value for the estimate of creatinine clearance, which is assumed to be equal to GFR, was 6.08 l h−1, or 101 ml min−1. Because PLC does not bind to plasma proteins [20], these data indicate extensive tubular reabsorption of PLC (about 95%), a finding which has been reported in vitro[10]. At a dose of 1 g, the time-averaged renal excretory clearance of PLC was 1.98 l h−1, or 33 ml min−1 (70% reabsorption) and for the 8 g dose, renal excretory clearance was 5.55 l h−1 (10% reabsorption). These data indicate that the renal handling of PLC in humans involves saturable tubular reabsorption. Because of this nonlinearity, renal-excretory clearance values calculated over short time-intervals are more meaningful than values estimated over a 24 h time period during which plasma concentrations may be fluctuating substantially. A plot of the ratio of renal-excretory clearance to creatinine clearance for PLC, as a function of plasma concentration indicates an apparent threshold concentration of 5–10 nmol ml−1, below which the ratio is relatively constant, and above which the ratio increases. An increase in this ratio signifies a reduction in fractional tubular reabsorption. At the highest plasma concentrations, the renal excretory clearance of PLC was of the same order of magnitude as creatinine clearance, suggesting that reabsorption is fully saturated. Thus, at the highest concentrations of PLC, most of the PLC filtered at the glomerulus escapes reabsorption. The observation that the ratio does not exceed unity suggests that there is no tubular secretion of PLC in the kidney.

The finding that the renal excretory clearance values for LC and ALC increased after administration of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride can be interpreted in a number of ways. The increased levels of LC and ALC in plasma (and therefore in tubular fluid) could have contributed to saturation of their respective tubular reabsorption processes. Given that there is likely to be competition between PLC, LC and ALC for the tubular reabsorption transport systems [10, 11], the reduced tubular reabsorption of LC and ALC may also have been due to the dramatic increase in the plasma concentrations of PLC. Renal metabolism of PLC to LC and ALC, followed by movement of the locally formed metabolites directly into urine (a phenomenon which has been observed in vitro[10]) could also be involved. In reality, all three mechanisms (saturation, competition and renal metabolism) are likely to be contributing to the observed changes in the renal excretory clearance of LC and ALC. However, preclinical studies [10, 11] have shown that LC (and ALC) in urine arise from two sources; that which is filtered at the glomerulus and escapes tubular reabsorption, and that which is formed in renal tubular cells from precursors such as PLC and transported directly into urine. As a consequence, renal metabolism of PLC can lead to substantial increases in the renal-excretory clearance estimates for LC and ALC. In the event of such a phenomenon, the measured renal-excretory clearance is not the true renal-excretory clearance of the circulating compound. For instance, after propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride administration, when the measured renal excretory clearance of LC is 100 ml min−1, then the renal excretory clearance of circulating LC may be substantially less. Similarly, a renal excretory clearance of LC exceeding the renal clearance of creatinine (Figure 2) should not necessarily be interpreted as evidence for secretion of circulating substrate. Rather, in the presence of high plasma concentrations of PLC, much of the LC appearing in urine is likely to arise not from the LC in plasma, but from the renal metabolism of PLC to LC, followed by leakage of a fraction of the formed metabolite directly into urine. This type of behaviour has been observed in the isolated perfused rat kidney preparation [9, 10]

The total clearance of PLC did not differ between the four dose groups, even though renal-excretory clearance increased substantially with dose. The is because the nonrenal-excretory clearance of PLC decreased with increasing dose. This result could signify that the clearance of the drug by organs other that the kidney also exhibits nonlinearity, and it may be that this is caused by saturable tissue uptake or saturable cellular metabolism. However, it is also possible that the increase in the renal-excretory clearance of PLC is itself the reason for the decrease in nonrenal-excretory clearance. The kidney is involved in the metabolism of PLC to LC and in the rat isolated perfused kidney, at endogenous PLC concentrations, the renal metabolic clearance of PLC greatly exceeds renal excretory clearance [10]. Because carrier-mediated tubular reabsorption of filtered PLC serves as a method of delivering PLC into renal tubular cells, it may be hypothesized that the metabolism of PLC in the kidney relies, to some extent, on the tubular reabsorption process. The logical extension of this concept is that if the fractional reabsorption was to decrease, then comparatively less drug (as a fraction of the total filtered amount) would be available for renal metabolism, and therefore while renal excretory clearance would increase, the renal metabolic clearance (which is incorporated into the ‘nonrenal-excretory clearance’ parameter) would decrease. According to this hypothesis, an increase in CLRav would be accompanied by a decrease in CLNR which might explain why the total clearance of PLC (CLRav+ CLNR) was constant with dose.

The amount of LC recovered in urine during the 24 h after the 1 g dose of propionyl-l-carnitine hydrochloride was substantially greater than that recovered in placebo-treated subjects, and represented 37.3% of the dose. The plasma levels of LC also increased markedly during and after dosing. These results suggest that LC is a major metabolite of PLC in humans. Studies in vitro have found that PLC is stable to hydrolysis in whole blood, but readily undergoes hydrolysis to LC on exposure to hepatic and renal homogenates [Longo A, personal communication]. Similarly, PLC labelled in the N-methyl position with carbon-11 was rapidly converted to labelled LC in rats [21] and in humans the same labelled compound was efficiently incorporated into the myocardial carnitine pool [22]. In the present study, the LC formed from PLC was likely to have been converted to ALC, resulting in the observed increases in the plasma and urinary levels of the acylated product. At the highest dose, about 80% was recovered in urine, and PLC, rather than LC, was the dominant species. These changes, with dose, in the absolute and relative recoveries of PLC and LC can be explained on the basis of the saturable tubular reabsorption of PLC.

References

- 1.Brevetti G, Perna S, Sabba C, Martone VD, Di Iorio A, Barlatta G. Effect of propionyl-l-carnitine on quality of life in intermittent claudication. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:777–780. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00867-3. 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00867-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brevetti G, Perna S, Sabba C, Martone VD, Condorelli M. Propionyl-l-carnitine in intermittent claudication: double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose titration, multicentre study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;26:1411–1416. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00344-4. 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00344-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiseman LR, Brogden RN. Propionyl-l-carnitine. Drugs Aging. 1998;12:243–250. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199812030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahl JJ, Bressler R. The pharmacology of carnitine. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1987;27:257–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.27.040187.001353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrari R, De Giuli F. The propionyl-l-carnitine hypothesis: an alternative approach to treating heart failure. J Card Fail. 1997;3:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9164(97)90018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Alaoui Talibi Z, Guendouz A, Moravec M, Moravec J. Control of oxidative metabolism in volume -overloaded rat hearts: effects of propionyl-l-carnitine. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H1615–H1624. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham VJ, Rosen SD, Boyd H, et al. Uptake of [N-methyl-11C]propionyl-l-carnitine (PLC) in human myocardium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:511–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davenport RJ, Law MP, Pike VW, Osman S, Poole KG. Propionyl–l–carnitine: labelling in the N–methyl position with carbon−11 and pharmacokinetic studies in rats. Nucl Med Biol. 1995;22:699–709. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(95)00010-u. 10.1016/0969-8051(95)00010-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancinelli A, Longo A, Nation RL, Evans AM. Disposition of l–carnitine (LC), acetyl–l–carnitine (ALC) and propionyl–l–carnitine in the rat isolated perfused liver. Proceedings of the Australasian Society of Clinical and Experimental Pharmacologists and Toxicologists. 1996;3:132. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans AM, Mancinelli A, Longo A. Excretion and metabolism of propionyl–l–carnitine in the isolated perfused rat kidney. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;281:1071–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mancinelli A, Longo A, Shanahan K, Evans AM. Disposition of l–carnitine and acetyl–l–carnitine in the isolated perfused rat kidney. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1122–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel AG, Rebouche CJ, Wilson DM, Glasgow AM, Romshe CA, Cruse RP. Primary systemic carnitine deficiency. II. Renal handling of carnitine. Neurology. 1981;31:819–825. doi: 10.1212/wnl.31.7.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uematsu T, Itaya T, Nishimoto M, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of l–carnitine infused i.v. in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;34:213–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00614562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segre G, Bianchi E, Corsi M, D'iddio S, Ghiriardi O, Maccari F. Plasma and urine pharmacokinetics of free and short–chain carnitine after administration of carnitine in man. Arzneimittel–Forschung/Drug Res. 1988;38:1830–1834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harper P, Elwin C–E, Cederblad G. Pharmacokinetics of bolus intravenous and oral doses of l–carnitine in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;35:69–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00555510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo A, Bruno G, Curti S, Mancinelli A, Miotto G. Determination of l–carnitine, acetyl–l–carnitine and propionyl–l–carnitine in human plasma by high–performance liquid chromatography after pre–column derivatization with 1–aminoanthracene. J Chromatogr. 1996;686:129–139S. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sahajwalla CG, Helton ED, Purich ED, Hoppel CL, Cabana BE. Multiple–dose pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence of l–carnitine 330–mg tablet versus 1–g chewable tablet versus enteral solution in healthy male volunteers. J Pharm Sci. 1995;84:627–633. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600840520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahajwalla CG, Helton ED, Purich ED, Hoppel CL, Cabana BE. Comparison of l–carnitine pharmacokinetics with and without baseline correction following administration of a single 20–mg/kg intravenous dose. J Pharm Sci. 1995;84:634–639. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600840521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker H, Frank O, De Angelis B, Baker ER. Absorption and excretion of l–carnitine during single or multiple dosing in humans. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1993;63:22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marzo A, Arrigoni Martelli E, Mancinelli A, et al. Protein binding of l–carnitine family components. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokin. 1991;(III):364–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davenport RJ, Law MP, Pike VW, Osman S, Poole KG. Propionyl–l–carnitine: labellin in the N–methyl position with carbon−11 and pharmacokinetic studies in rats. Nucl Med Biol. 1995;22:699–709. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(95)00010-u. 10.1016/0969-8051(95)00010-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham VJ, Rosen SD, Boyd H, et al. Uptake of [N–methyl−11C]propionyl–l–carnitine (PLC) in human myocardium. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:511–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]