Abstract

Aims

The primary objective of this study was to determine how the pharmacokinetics of sabeluzole, an investigational drug with specific effects on memory and learning abilities, are affected by chronic liver disease. Since sabeluzole is metabolised by CYP2D6, a secondary objective was to study the correlation between CYP2D6 activity (as assessed by the dextromethorphan dextrorphan metabolic ratio) and hepatic dysfunction.

Methods

The single-dose pharmacokinetics of sabeluzole (10 mg) was compared in 10 healthy Caucasian subjects and 10 patients with severe hepatic dysfunction. The urinary dextromethorphan/dextrorphan (DMP/DRP) metabolic ratio was determined after intake of 20 mg dextromethorphan (NODEX® capsules).

Results

The terminal half-life of sabeluzole was significantly prolonged in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction vs healthy subjects (respectively 39.3 ± 11.5 h; 17.5 ± 10.2 h (mean ± s.d.)). The areas under the curve (AUC) were significantly higher in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction than in healthy volunteers (681 ± 200 ng ml −1h vs 331 ± 282 ng ml −1h). There was a significant correlation between the AUC(0,∞) and the DMP/DRP metabolic ratio in healthy volunteers and subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction. AUC was greater and elimination of sabeluzole slower in poor metabolizers compared with extensive metabolizers.

Conclusions

These results suggest that a) sabeluzole dose should be reduced in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction and b) the AUC of sabeluzole is linked to individual CYP2D6 activity.

Keywords: chronic liver disease, dextromethorphan oxidation, pharmacokinetics, sabeluzole

Introduction

Sabeluzole, 4-[(2-benzothiazolyl)methylamino]-a-[(4-fluorophenoxy)methyl]-1-piperidine-ethanol, is a benzothiazole derivative. In healthy volunteers, chronic treatment with sabeluzole enhances both learning and recall in conditions of age-related mild hypofunction [1, 2]. In a geriatic population with mean age of 85 years, sabeluzole significantly improved retrieval functions in the poor performance group [3].

In humans, aromatic hydroxylation at the 6-position of the benzothiazole moiety and glucuronidation of sabeluzole and its metabolites are the main metabolic pathways. Renal excretion of the parent substance is less than 0.5%, pointing to metabolism as the major route of elimination.

The polymorphically expressed enzyme CYP2D6 [5–7] seems to be responsible for the 6-hydroxylation of sabeluzole. Thus, in healthy volunteers given a single dose of sabeluzole and phenotyped with dextromethorphan, poor metabolisers formed very little of this metabolite compared with extensive metabolisers [4].

In addition to these genetic factors, drug oxidation may depend on liver function. Cirrhosis is associated with approximately a 50% decrease in hepatic cytochrome P450 [10]. Larrey and colleagues (1989) [11] have demonstrated that dextromethorphan oxidation capacity is impaired in patients with chronic liver disease.

The primary aim of this study was to compare the pharmacokinetics of sabeluzole in healthy volunteers and subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction. Since one of the major metabolic pathways of sabeluzole metabolism in human involves CYP2D6, a secondary aim of this work was to test for a correlation between sabeluzole pharmacokinetic parameters and CYP2D6 activity, using the dextromethorphan metabolic ratio, and to assess whether individual differences in CYP2D6 activity were related to hepatic dysfunction.

Methods

The clinical part of the study was performed at the Centre de Pharmacologie Clinique et d'Evaluations Thérapeutiques, Hôpital de la Timone, 3385 Marseille, France. The trial was coordinated by the Clinical Research Department of the Laboratoires Janssen-Cilag, Boulogne Billancourt, France) and by the Pharmacokinetics Department (Janssen Research Foundation, Research Center, Val de Reuil, France). This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 as revised in Hong Kong 1989 and after approval by the Comité Consultatif de Protection des Personnes dans la Recherche Biomédicale de Marseille (CCPPRB, France). Before admission to the trial, all subjects gave written informed consent.

Subjects

Ten male healthy Caucasian subjects, between 40 and 64 years old (mean age = 53.5 years) and with a body weight between 62 and 94 kg (mean=75.8 kg) were paired with 10 male Caucasian subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction aged between 39 and 63 years old (mean age = 54.8 years) and weighing between 59 and 85 kg (mean=74.7 kg).

All subjects smoked less than 10 cigarettes a day and were within 10% of their ideal weight as calculated by the formula of Lorentz: W = H−100 − (H−150)/4 (males), where W=weight and H=height.

Prior to the start of the investigations, the healthy subjects were judged by the clinical investigator to be in good health, based on a physical examination, electrocardiogram and the results of blood biochemistry, haematology and urinalysis.

Subjects who had taken conventional medication in the 7 days preceding the study or use of sustained-release drugs in the month before were excluded. In order to avoid potential drug interactions with sabeluzole, these subjects were asked not to use any medication other than sabeluzole during the study.

Hepatic dysfunction was confirmed by medical history, physical examination and prothrombin time or a V Leiden coagulation factor of less than 60%. The mean plasma albumin concentration was 32 g l−1. One patient was classified as having A grade disease with 5 Child-Pugh scores, six patients were classified as B grade with 7–9 Child-Pugh scores and three patients were classified as C grade with 10 scores. The causes of hepatic dysfunction were alcohol abuse in nine cases and hepatitis in one case. No patient received concomittant treatment known to be a potential substrate or inhibitor of CYP2D6.

Protocol

Dextromethorphan For CYP2D6 phenotyping, all subjects were administered a 20 mg dextromethorphan capsule (NODEX®) and the DMP/DRP metabolic ratio was estimated from an aliquot of a complete 0–8 h urine sample. Dextromethorphan intake was between 14 and 7 days before sabeluzole. The poor metaboliser phenotype (PM) was characterized by a metabolic ratio above 0.3 in healthy volunteers [8, 9, 12] and patients with severe hepatic dysfunction [11].

Sabeluzole pharmacokinetics After an overnight fast of at least 10 h, a single 10 mg tablet of sabeluzole was administered orally with 50 ml of water between 08.00 h and 09.00 h and 15 min after a standard breakfast. Lunch was taken 4 h after sabeluzole intake. Thereafter, subjects resumed their usual diet. Alcoholic beverages were not allowed 24 h before and 24 h after drug intake.

Side-effects were monitored continuously throughout the study. Blood pressure and heart rate were recorded before and 30, 45, 60, 90 min, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 and 12 h after intake of sabeluzole, in the recumbent position.

Blood samples (about 8 ml) for drug analysis were taken from an antecubital vein 5 min before and at 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 34, 48, 72 and 96 h after sabeluzole intake. Blood was collected into heparinized tubes and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 g. Plasma was aspirated with a disposable Pasteur pipette and transferred into 5 ml plastic polypropylene tubes. Samples were stored at −20 °C until assay.

Bioanalysis

Dextromethorphan/dextrorphan Urinary concentrations of dextromethorphan and its O-demethylated metabolite dextrorphan were determined by a validated h.p.l.c. method [13]. The limit of quantification for the assay was 0.2 µg ml−1. Precison and accuracy measurements were performed at concentrations between 0.01 and 1 µg ml−1 for dextromethorphan and between 0.5 and 25 µg ml−1 for dextrorphan. Coefficients of variation were 4.3–8.5% and 0.4–2.1% for dextromethorphan and dextrorphan, respectively. Estimates of accuracy were 100–113% and 96–108% for dextromethorphan and dextrorphan, respectively.

Sabeluzole Plasma concentrations of sabeluzole were measured using a h.p.l.c.-u.v. method developed and validated internally by Janssen-Cilag [data on file, reference –14]. Plasma samples (1 ml), spiked with the internal standard (RO56193), were alkalinized and extracted with 7 ml heptane-isoamyl alcohol (98.5/I.5; v/v). The organic phase was back-extracted with 3 ml 0.05 m sulphuric acid and removed after centrifugation. The remaining acidic phase was made alkaline and re-extracted with 6 ml of heptane-isoamyl alcohol mixture, then evaporated to dryness and analysed by h.p.l.c. after dissolution of the residue with 0.1 ml of the h.p.l.c. mobile phase. U.v. detection was set at 273 nm. The reverse phase column (15 cm×2.1mm i.d.) contained Hypersil® C18 (5 µm particle size). The compounds were eluted with 0.025 m ammonium acetate buffer (pH 9.5)-methanol-acetonitrile (25–35–40 by volume) at a constant flow rate of 0.5 ml min−1. The accuracy and precision of the assay was derived from analyses of quality control samples independently prepared in human plasma. For sabeluzole, the overall precision (interassay coefficient of variation) and accuracy were 5.2% and 96.1% (n = 61 replicates), respectively. The limit of quantification was 2 ng ml−1 and the calibration range was from 2 to 200 ng ml−1.

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to reach the peak plasma concentration (tmax) were obtained directly. The terminal elimination rate constant (λz) was determined [15] using a nonlinear least squares method with a peeling algorithm (SIPHAR, SIMED, Créteil, France). The terminal half-life (t1/2,λz) was calculated as 0.693/λz. The area under the plasma concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h was calculated by linear trapezoidal summation (AUC(0,24h)). The area extrapolated to infinity (AUC(0,∞)) was calculated from the equation AUC(0,t) + CT/λz where CT is the last quantifiable concentration at time t.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the pharmacokinetic parameters and the plasma concentrations of sabeluzole at each sampling time. Statistical comparison between healthy subjects and subjects with hepatic disease was performed using analysis of variance (anova, 1 way) for Cmax, t1/2,λz, AUC(0,24h), AUC(0,∞) on both the original and the log-transformed data. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used for comparisons of tmax. Blood pressure and heart rate were compared between healthy subjects and subjects with hepatic dysfunction using repeated analysis of variance. All tests were two-tailed and differences were considered statistically significant at the 5% level. Correlation between AUC(0,∞) and metabolic ratio was assessed with the Spearman rank test.

Results

Both healthy subjects and patients tolerated sabeluzole well and no serious side-effects were reported. One subject with severe hepatic dysfunction reported two mild side-effects, diarrhoea and drowsiness. No statistically significant change was observed for any of the biochemistry and haemodynamic parameters with respect to drug treatment and liver disease.

Pharmacokinetics

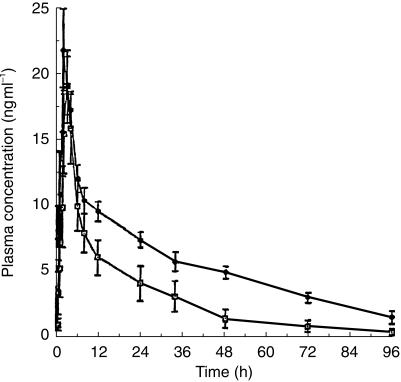

The mean pharmacokinetic parameters of sabeluzole are shown in Table 1 and the mean concentration-time data in Figure 1. While no statistically significant differences were observed for mean values of tmax and Cmax between the two groups of subjects, the AUCs were statistically significantly higher in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction than in healthy volunteers. In addition, mean t1/2,λz of sabeluzole was prolonged significantly in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction. Plasma concentrations of sabeluzole were below the limit of quantification after t = 8 h in one subject and after t = 12 h in two others.

Table 1.

Comparison of pharmacokinetic parameters between healthy and liver disease subjects after single oral dosing of 10 mg sabeluzole tablet.

| Healthy subjects (n = 10) | Liver disease subjects (n = 10) | 95% CI for difference | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tmax (h) | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | −0.78; 0.98 | NS |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 21.6 ± 9 | 25.9 ± 11.0 | −4.51; 13.11 | NS |

| AUC(0,24h) (ng ml−1 h) | 158 ± 110 | 255 ± 56 | 20.5; 173.5 | P < 0.05 |

| AUC(0,∝) (ng ml−1 h) | 331 ± 282 | 681 ± 200 | 135.7; 564.3 | P < 0.01 |

| λz (h−1) | 0.0741 ± 0.087 | 0.0191 ± 0.0055 | 0.00087–0.109 | NS |

| t½λz (h) | 17.5 ± 10.2 | 39.3 ± 11.5 | 12.3; 31.3 | P < 0.001 |

Data represent mean±s.d. NS: no significant.

Figure 1.

Mean (± s.e. mean) plasma concentration-time profiles for sabeluzole in healthy volunteers (□, n = 10) and subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (•, n = 10).

Two healthy subjects were classified as poor metabolisers (metabolic ratios 10.8 and 2.5). The mean (± s.d.) metabolic ratio of the eight healthy extensive metabolisers was 0.006 (± 0.013). Three subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction were classified as poor metabolisers (metabolic ratios 0.350, 0.736 and 1.990). The other patients were extensive metabolisers (mean±s.d. of metabolic ratio=0.161 ± 0.068).

The mean AUC(0,∞) of sabeluzole for the eight healthy extensive metabolisers was 311 ± 224 ng ml −1h whereas it was at 582 and 937, respectively, for the two healthy poor metabolisers. In the subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction, the mean AUC(0,∞) of sabeluzole was 626 ± 193 ng ml −1h whereas it was at 612, 849 and 970, respectively, for the three other poor metabolisers. There was a statistically significant correlation between the AUC(0,∞) and the metabolic dextromethorphan ratio when the data from healthy volunteers and subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction were combined (rs = 0.855, P < 0.001).

Discussion

The present study has shown that the mean AUC and terminal half-life of sabeluzole in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction was increased by 106% and 125%, respectively, suggesting an increase in bioavailability, as compared with healthy subjects of comparable age and body weight. These difference observed in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction can probably be attributed to a diminution of the hepatic metabolism of sabeluzole. These findings suggest that sabeluzole dose should be reduced in patients with chronic liver disease.

The observed correlation between AUC of sabeluzole and DMP/DRP urinary ratio suggests that healthy poor metabolisers with respect to CYP2D6 and possibly those with severe hepatic dysfunction show an impaired elimination of sabeluzole compared with extensive metabolisers. Severe hepatic dysfunction has been shown to be associated with approximately 50% decrease in hepatic cytochrome P450 content [10], but Rautio et al. have observed that CYP2D6-dependent reactions were less disturbed than those mediated by CYP2C19 or CYP3A4 [16].

Larrey et al. comparing 56 patients with cirrhosis, 51 with moderately severe liver disease and 103 controls, found that the mean dextromethorphan metabolic ratio in cirrhotic patients was still six times lower than that corresponding to the antimode separating EM and PM phenotype [11], suggesting that cirrhosis or moderate liver disease does not affect the assignment of the EM and PM phenotype determined by this method [17]. In our study, most of the subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction were characterized as EMs (metabolic ratio < 0.3), but it is clear that they had much higher metabolic ratios than the healthy EMs, indicating that their oxidation capacity was reduced because of liver disease.

In conclusion, these data indicate that dosage adjustment of sabeluzole doses should be required in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction. They suggest also that sabeluzole the AUC of sabeluzole is linked to individual CYP2D6 activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Dominique Larrey, Service d'Hepatogastroenterologie et Transplantation, CHU Saint Eloi, Montpellier, for his advice and guidance.

References

- 1.Clincke G, Tristmans L. Sabeluzole (R 58735) increases consistent retrieval during serial learning and relearning of nonsense syllables. Psychopharmacology. 1988;96:164–168. doi: 10.1007/BF00216055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tristmans L, Clincke G, Amery WK. The effects of sabeluzole ( R58735) on memory retrieval functions. Psychopharmacology. 1988;94:527–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00212849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tristmans L, Clincke G, Devenijns F, Verhoosel G, Amery WK. Memory study with sabeluzole in population with a mean age of 85 years: a pilot experiment. Curr Ther Res. 1988;44:966–974. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannens G, Meuldermans W, Heykants J, Van Rooy P. The absorption, metabolism and excretion of sabeluzole after a single oral dose in man. Janssen: Janssen Research Foundation; Clinical Research Report on trial SAB-BEL-37. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahgoub A, Idle JR, Dring LG, Lancaster R, Smith RL. Polymorphic hydroxylation of debrisoquine in man. Lancet. 1977;ii:584–586. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)91430-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larrey D, Amouyal G, Tinel M, et al. Polymorphism of dextromethorphan oxidation in a French population. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;24:676–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duché JC, Quérol-Ferrer V, Barré J, Mésangeau M, Tillement JP. Dextromethorphan O-demethylation and dextrorphan glucuronidation in a French population. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1993;31:392–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daly AK, Fairbrother KS, Andreassen OA, London SJ, Idle JR, Steen VM. Characterisation and PCR-based detection of two different hybrid CYP2D7P/CYP2D6 alleles asociated with the poor metabolizer phenotype. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6:319–328. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199608000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gonzalez FJ, Idle JR. Pharmacogenetic phenotyping and genotyping. Present status and future potentiel. Clin Pharmacokin. 1994;26:59–70. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199426010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howden CW, Birnie GG, Brodie MJ. Drug metabolism in liver disease. Pharmacol Ther. 1989;40:439–474. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(89)90088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larrey D, Babany G, Tinel M, et al. Effect of liver disease on dextromethorphan oxidation capacity and phenotype: a study of 107 patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:297–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb05430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kupfer A, Schmid B, Pfaff G. Pharmacogenetics of dextromethorphan O-demethylation in man. Xenobiotica. 1986;16:421–433. doi: 10.3109/00498258609050249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leguellec C, Lacarelle B, Giocanti M, Durand A. HPLC assay for dextromethorphan: application to the determination of cytochrome P4502D6 (CYP2D6) oxidation phenotype. J Pharm Clin. 1994;13:40–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woestenborghs R, Lorreyne W, Van Rompaey F, Heykants J. Determination of sabeluzole (R 58735) in plasma and animal tissue by high performance liquid chromatography. Janssen Research Foundation; 1987. Preclinical Research Report R 58735/17 December. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gomeni G. Pharm: an interactive graphic program for individual and population pharmacokinetics parametre estimation. Comput Biol Med. 1984;14:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0010-4825(84)90017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rautio A, Salmela E, Aevela P, Pelkonen O, Sotaniemi EA, Lechner MC. Cytochrome P450: Eight International Conference Paris. John Libbey Eurotext; 1994. Assessment of CYP 2A6 and CYP 3A4 activities in vivo in different diseases in man; pp. 519–521. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanthier PL, Reshef R, Shah RR, Oates NS, Smith RL, Morgan MY. Oxidation phenotyping in alcoholics with liver disease of varying severity. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res. 1984;8:435–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]