Abstract

Aims

Lacidipine, a long acting 2, 4-dihydropyridine calcium channel antagonist is frequently administered with cholesterol lowering agents, particularly in elderly populations. The effects of lacidipine on the pharmacokinetics of simvastatin were investigated, since they share the CYP3A4 pathway for metabolism.

Methods

The study was an open, randomised, two-way crossover design, with at least 7 days washout. Eighteen healthy subjects received simvastatin, 40 mg once daily, alone and together with lacidipine, 4 mg once daily, for 8 days. The pharmacokinetics of simvastatin were studied on the eighth day. Analysis was made of total simvastatin acid concentrations (naive simvastatin acid plus that derived from alkaline hydrolysis of the lactone).

Results

Lacidipine increased the maximum concentration of simvastatin (Cmax) by approximately 70% (P = 0.016) and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve AUC(0,24 h) by approximately 35% (P = 0.001). The mean Cmax and AUC(0,24 h) of simvastatin (95% confidence interval) when given alone were 8.76 (6.72–11.41) ng ml−1 and 60.36 (47.15–77.28) ng ml−1 h. During treatment with lacidipine they were, respectively, 14.89 (10.77–20.58) ng ml−1 and 80.96 (64.62–101.44) ng ml−1 h. No significant differences were observed in either time to peak concentration (tmax was 1.0 h for simvastatin alone and 1.5 h for the combination) or in the half-life (t1/2,z was 8.5 h in both cases). The combination was safe and well tolerated.

Conclusions

The observed increased exposure to simvastatin 40 mg following coadministration of lacidipine is unlikely to be of clinical relevance.

Keywords: HMGCoA reductase inhibitors, interaction, lacidipine, simvastatin

Introduction

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey II (USA) [1] found that 40% of hypertensive subjects had elevated total cholesterol concentrations (≥240 mg dl−1). These patients may need chronic combined treatment for both hypertension and hyperlipi daemia. Some antihypertensives exert adverse effects on the plasma lipid profile [2], thus their use is contraindicated in patients with elevated lipids lipoproteins−1. Lacidipine, a 2, 4-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker with well-proven efficacy and good tolerability [3], does not adversely affect carbohydrate and lipid metabolism [4].

Inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase are currently used as first-line therapy for the treatment of hypercholesterola emia. For these drugs, hepatotoxicity and myotoxicity are the most common serious adverse events. Concomitant treatment with cyclosporin and lovastatin may lead to rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure [5, 6]. Plasma concentrations of lovastatin and simvastatin are elevated by concomitant treatment with cyclosporin [7, 8], a known substrate of CYP3A4 [9]. Similarly, grapefruit juice affects both lovastatin and simvastatin metabolism [10, 11], thus confirming the specific sensitivity of these two drugs to CYP3A4 substrates/inhibitors. Also the new calcium channel antagonist mibefradil has been recently reported to cause serious drug interactions, mainly with HMGCoA reductase inhibitors and particu larly with simvastatin [12]. Similarly, the calcium channel antagonist diltiazem increases lovastatin concentrations [13] and selectively inhibits the clearance of [R]-warfarin [14] which, is primarily metabolized by CYP1A2 and CYP3A4 isoenzymes [15]. Lacidipine undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism and is metabolized mainly by the CYP3A4 pathway, as are many other dihydropyridines [16]. Although indirect evidence of lack of inhibitory activity of lacidipine on CYP3A4 enzymes can be obtained from lack of a pharmacokinetic interaction with [R]-warfarin [17], its potential effects on the pharmaco kinetics of simvastatin were investigated.

Methods

Subjects

The investigation was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of Glaxo Wellcome SpA (Verona, Italy) and conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and amendments in the Glaxo Wellcome Clinical Pharmacology Unit (Verona, Italy). Written informed consent was obtained from 18 healthy Caucasian subjects (11 M, 7F) age range 19–40 years (mean±s.d., 28.8±7.2 years), weight range 54–80 kg (mean±s.d., 67.0±8.5 kg, Table 1). There were nine smokers and nine nonsmokers and none was on chronic medication except for one woman on oral contraceptive steroids. A sample size of 18 subjects would have provided 80% power to detect a 25% change in AUC(0,24 h) of simvastatin–hydroxy acid when administered with lacidipine. This calculation was based on an estimate of within-subject variability of about 23%. The subjects underwent a clinical examination, electrocardiogram (ECG) and laboratory tests including clinical chemistry, haematology and urinalysis.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for pharmacokinetic parameters of simvastatin hydroxy acid on day 8 of 40 mg day−1 simvastatin administration alone and together with 4 mg lacidipine.

| Simvastatin alone | Simvastatin+lacidipine | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Weight (kg) | AUC(0,24 h) (ng ml−1 h) | Cmax(ng ml−1) | t1/2 (h) | tmax (h) | AUC(0,24 h) (ng ml−1h) | Cmax(ng ml−1) | t1/2 (h) | tmax (h) | |

| Mean | 28.8 | 67.0 | 66.50 | 10.03 | 9.7 | 1.3 | 88.20 | 18.35 | 10.0 | 2.2 |

| s.d. | 7.2 | 8.5 | 26.34 | 5.53 | 5.9 | 1.1 | 37.70 | 14.83 | 6.5 | 1.9 |

| CV% | 39.6 | 55.2 | 60.4 | 81.1 | 42.7 | 80.8 | 65.0 | 84.9 | ||

| Median | 67.4 | 8.14 | 9.0 | 1.0 | 80.07 | 15.35 | 8.1 | 1.5 | ||

| Minimum | 19 | 54 | 14.44 | 3.65 | 3.8 | 0.5 | 28.01 | 5.14 | 3.5 | 0.5 |

| Maximum | 40 | 80 | 109.06 | 22.15 | 25.6 | 4.0 | 177.07 | 68.14 | 28.6 | 6.0 |

Cmax = peak plasma concentration, tmax = time to reach Cmax, AUC(0,24 h) = area under the plasma concentration-time curve from 0 to 24 h, Mean = arithmetic mean, s.d. = standard deviation, CV% = coefficient of variation percentage.

Study design

The study was an open, randomised, crossover design, in two periods, separated by a 7 days washout. On each treatment period, subjects took simvastatin 40 mg once a day either alone or together with lacidipine 4 mg once daily, with 200 ml water, in the morning, for 8 consecutive days, regardless of food intake. On the 8th day of each study period subjects took the drugs after a 10 h fast and had a standard meal 4 h afterwards. For 24 h before and during each treatment period, subjects were asked to refrain from citrus fruits (particularly grapefruit).

The present study was designed to maximize the extent of any possible interaction at the given doses and should represent a ‘worst case’ scenario as far as an interaction on a ‘first pass’ effect of the two drugs is concerned. Simvastatin and lacidipine were given together in the morning, whereas the dosing recommendation (particularly to optimize the lipid lowering effect) is preferably to take lacidipine in the morning and simvastatin in the evening. The clinical relevance of possible increased exposure to simvastatin, 40 mg, following lacidipine 4 mg coadministration, was judged on the basis of the therapeutic window of simvastatin (i.e. 10–80 mg once daily).

Blood sampling

On the 8th day of each treatment period, a plastic cannula was inserted into a forearm vein of each subject and kept patent with 1 ml heparinized saline (5 U ml−1 normal saline). Blood samples (10 ml) for analysis of plasma lacidipine concentrations were taken into foil-covered Lithium Heparin Sarsted Monovette tubes at the following time points: predose, 1 and 2 h after dosing. Samples for lacidipine determination were placed on ice until they were centrifuged at 1500 g at 4 C for 10 min. Plasma was transferred into foil-covered tubes and stored at −20 C pending analysis. Blood samples (2.5 ml) for plasma simvastatin assay were taken at the following time points: predose, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24 h after dosing. After collection samples were placed on ice until centrifugation (1500 g at 4 C for 10 min). The plasma fraction was transferred into tubes and stored at −70 C until assay.

Safety and tolerability

A medical evaluation, including ECG and blood pressure measurement and laboratory tests (haematology, biochem istry, urinalysis, screening tests for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus in serum and for drugs of abuse in urine) were performed at prestudy. Haematology, biochemistry and urinalysis were repeated at poststudy. Laboratory screening of liver enzymes, creatine kinase (CK), aldolase (ALD) and pregnancy test in urine were performed at prestudy, on the 1st and the 8th day of each treatment period and at poststudy. Subjects were asked at each visit about the occurrence of adverse events by nonleading questions.

Determination of simvastatin by GC-MS and lacidipine by h.p.l.c.-r.i.a

All assays were performed at the ‘A.Marxer’ RBM laboratory (Torino, Italy). For simvastatin a validated gas chromatographic method with negative chemical ioniz ation mass spectrometry detection (GC-MS) was used, based on a published method [18]. Total simvastatin -hydroxy acid concentrations were determined after alkaline hydrolysis of the samples. This procedure accounted for all potentially active compounds; that is the naive acid form plus the one derived by the opening of the drug's lactone ring. After solid phase extraction on C18-SPE columns, samples were derivatized with 2,3,4,5,6-pentafluorobenzyl bromide (PFB), followed by a second derivatization with a mix of N,O-Bis (trimethyl silyl), trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) and trimethylchlorosil ane (TMCS). For the GC separation, on an Ultra 1 chromatographic column (Hewlett Packard), helium was used as a carrier gas. Quantification was performed by measurement of the peak area ratios of simvastatin to internal standard (mevastatin). The lower limit of quantification (LOQ) was 0.5 ng ml−1 and the intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) at this concentration was 6.6%.

Plasma concentrations of lacidipine were determined using a validated high-performance liquid chromatogra phy-radioimmunoassay method (h.p.l.c.-r.i.a.) [19]. The LOQ was 0.042 ng ml−1 and the intrarun CV was between 1.1% and 14.9% at concentration range from 1 to 10 ng ml−1.

Pharmacokinetic calculations

The pharmacokinetic analysis of simvastatin concentration data was performed using noncompartmental methods. AUC(0,24 h) was calculated using the linear trapezoidal rule. The elimination rate-constant (λz) was estimated by log-linear regression analysis of the terminal phase of the plasma simvastatin concentration-time profile. The terminal half-life was calculated by t1/2,z=0.693/λz. Three to seven concentration data points were used for half-life estimation. Three points were used to estimate terminal half-life in five cases out of 18 and seven out of 17 following administration simvastatin alone and in combination, respectively.

Lacidipine plasma concentrations were summarized as median (range) values and compared with previously reported data.

Statistical analysis

Individual ratios were calculated for simvastatin AUC(0,24 h) and Cmax between the two treatments. The log-transformed AUC(0,24 h), Cmax and t1/2,z were analysed by analysis of variance, allowing for effects due to sequence, subjects (within sequence), period and treatment. Estimates of geometric mean ratios between simvastatin with lacidipine and simvastatin alone were calculated together with 90% confidence intervals and tested for significance.

Values of tmax were compared using Koch's nonpara metric method for a two-period crossover, based on the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test. An estimate of the median difference between treatments with a 90% confidence interval was calculated.

Results

Pharmacokinetics

Figure 1a and b show individual values of simvastatin AUC (0,24 h) and Cmax following the two treatments.

Figure 1.

Comparative plot of individual simvastatin acid AUC(0,24 h) (ng ml−1 h) and Cmax (ng ml−1) following 8 days oral administration of 40 mg simvastin alone or with lacidipine 4 mg. Thick line shows median. (Note the logarithmic scale.)

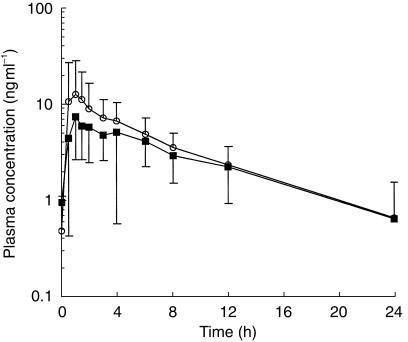

A small increase in the concentration of simvastatin acid, which was statistically significant, was observed after concomitant administration of lacidipine (Table 2, Figures 2 and 3). The average simvastatin AUC(0,24 h) increased by approximately 35% (range 18% to 53%, P = 0.001). The mean increase in Cmax was approximately 70% (range 20% to 137%, P = 0.016). No significant differences were observed in either time to peak concentration (tmax, P = 0.143), or in the half-life (t1/2,z, P = 0.955).

Table 2.

Estimates of geometric mean values (and 95% confidence intervals) of the simvastatin-acid pharmacokinetic parameters and treatment comparisons, expressed as ratios of treatment estimates, together with 90% confidence intervals.

| Ratio estimate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simvastatin-acid pharmacokinetic parameter | Simvastatin alone (A) | Simvastatin+Lacidipine (B) | B/A | 90% CI | P value |

| AUC(0,24 h) (ng ml−1 h) | 60.36 (47.15, 77.28) | 80.96 (64.62, 101.44) | 135% | 118%, 153% | 0.001 |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 8.76 (6.72, 11.41) | 14.89 (10.77, 20.58) | 169% | 120%, 237% | 0.016 |

| t1/2 (h) | 8.5 (6.6, 10.9) | 8.5 (6.4, 11.4) | 101% | 77%, 132% | 0.955 |

| tmax (h) | 1.0 (0.5, 4.0)† | 1.5 (0.5, 6.0)† | 0.5 (h)§ | 0.0, 2.0 (h)§ | 0.143 |

Median and range

Estimate is median difference between the two treatments.

Figure 2.

Linear plots of simvastatin-acid mean (and s.d.) plasma concentrations (ng ml−1) following 8 days oral administration of simvastatin 40 mg alone (▪) or with lacidipine 4 mg (○).

Figure 3.

Semilogarithmic plots of simvastatin-acid mean (and s.d.) plasma concentrations (ng ml−1) following 8 days oral administration of simvastatin 40 mg alone (▪) or with lacidipine 4 mg (○).

Median plasma concentrations of lacidipine measured predose, 1 h and 2 h following administration were 0.06 [range below the LOQ (BQL) to 2.1] ng ml−1, 0.99 (range 0.17–11.23) ng ml−1 and 0.68 (range 0.22–5.06) ng ml−1, respectively. They were similar to data previously reported [20].

Safety and tolerability

Seventeen of the 18 enrolled subjects completed the study. One subject was withdrawn because of recurrent headaches. No serious adverse events occurred during the study. Minor adverse events (mainly headaches and palpitations) were transient and, in the majority, were reported as mild to moderate disturbances. They had already been reported following lacidipine similarly to most dihydropyridines. The number of subjects reporting minor adverse events was 12 for simvastatin alone and 15 for simvastatin+lacidipine treatment. Seven subjects reported headache with simvastatin treatment whereas 12 subjects reported it with simvastatin+lacidipine treat ment. Two subjects reported palpitations following simvastatin+lacidipine treatment. No clinically relevant changes were observed in the laboratory safety tests, neither during the study nor at the follow-up.

Discussion

Lovastatin and simvastatin are known to undergo extensive first-pass metabolism, mediated mainly by the CYP3A4 subfamily [20, 21]. Because of the potential serious adverse events associated with high plasma concentrations of these statins, the concomitant use of substrates or inhibitors of CYP3A4 should be appropriately considered. Some heart transplant recipients on cyclosporin plus lovastatin were shown to develop rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure [5, 6] and a major cause of mibefradil withdrawal was the frequent harmful interaction with simvastatin [22]. Grapefruit juice, a well-known CYP3A4 inhibitor, increased the lovastatin AUC and Cmax, 15-fold and 12-fold, respectively [10] and the simvastatin AUC and Cmax 9-fold and 16-fold, respectively [11]. Similar, itraconazole, another potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, was found to increase the Cmax and AUC of lovastatin and lovastatin acid, on average, more than 20-fold [23] and the total simvastatin acid Cmax and AUC, on average, more than 17-fold [24]. AUC and Cmax of pravastatin, a statin undergoing a limited ‘first pass’ metabolism, were increased less than two-fold by itraconazole [24]. Fluvastatin, metabolized by CYP2C9 pathway [25], was not significantly influenced by itraconazole [26]. Cerivastatin similarly to pravastatin undergoes a reduced ‘first pass’ metabolism and plasma concentrations were not significantly increased by erythromycin [27]. Despite the high concentrations of simvastatin and simvastatin acid when coadministered with CYP3A4 inhibitors, the HMG-CoA inhibitory activity AUC and Cmax increased only from 3-fold to 5-fold [11, 24]. In an in vitro study, the risk of myopathy was higher with the lipophilic HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin than with a hydrophilic derivative [28]. Lipophilic compounds more effectively penetrate the skeletal muscle cell membrane. Thus, in the present study, total simvastatin concentrations have been analysed instead of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitory activity as the risk of myopathy seems to be better correlate with the plasma concentration of the lipophilic parent drugs than with their more polar metabolites.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate possible pharmacokinetic interactions between simvastatin and lacidipine as they share the CYP3A4 metabolic pathway and the combination of dihydropyridines with cholesterol lowering agents seems to be clinically appropriate. Retrospective data from a long-term angiographic study [29] showed synergistic potential effects of dihydropyridines and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors in retarding progression of coronary atherosclerosis. In particular, lacidipine was shown, in vitro, to prevent the adhesion of monocytes to the endothelium, an early event in atherosclerosis, by interfering with cell adhesion molecules [30].

Regular doses used of lacidipine are up to 4 mg and for simvastatin up to 40 mg. These have been administered in the present study. Lacidipine does not consistently affect drug elimination, as simvastatin terminal half-life is unchanged. This finding suggests that the effects of lacidipine on the pharmacokinetics of simvastatin probably occur in the absorption phase, possibly reducing the first pass metabolism of simvastatin.

After 1 week cotreatment, lacidipine 4 mg once daily increases the total exposure to simvastatin 40 mg once daily by approximately 35%. Simvastatin is reported to have dose-proportional pharmacokinetics up to the 160 mg [31, 32] and an exploration of the simvastatin expanded-dose tolerability suggests that simvastatin is safe and well tolerated up to at least 80 mg daily [32, 33]. Therefore, observed increased exposure has not exceeded the therapeutic window for simvastatin, so is unlikely to be of clinical relevance either for safety or tolerability.

Furthermore, simvastatin and lacidipine were given together in the morning, whereas, according to dosing recommendations, lacidipine should be taken in the morning and simvastatin in the evening. This design has had the specific purpose to maximize any possible interaction and represents a ‘worst case’ scenario at the given doses that is unlikely to occur in routine drug therapy.

In summary, 4 mg lacidipine has relatively minor effects on the pharmacokinetics of 40 mg simvastatin in a single dose. These effects may arise in part from competition for the CYP3A4 mediated route of metabolism.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the valuable support of Professor C. Sirtori for discussion and suggestions. This study was funded entirely by Glaxo Wellcome.

References

- 1.Working group on management of patients with hypertension and high blood cholesterol. National Education Program Working Group report the management of patients with hypertension and high blood cholesterol. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:224–237. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-3-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lardinois CK, Neuman SL. The effects of antihypertensive agents on serum lipids and lipoproteins. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1280–1288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tcherdakoff P. and the Investigators of study LAC-05–91. French large-scale study evaluating the tolerability and efficacy of lacidipine. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;25(Suppl 3):s27–s32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spieker C, Zidek W. The impact of lacidipine, a novel dihydropyridine calcium antagonist, on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;25(Suppl 3):s23–s26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.East C, Alivizatos PA, Grundy SM, Jones PH, Farmer JA. Rhabdomyolysis in patients receiving lovastatin after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:47–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198801073180111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copier CL, Jones PH, Suki WN, et al. Rhabdomyolysis and renal injury with lovastatin use. JAMA. 1988;260:239–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kliem V, Wanner C, Eisenhauer T, et al. Comparison of pravastatin and lovastatin in renal transplant patients receiving cyclosporine. Transplant Proc. 1996;28:3126–3128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnadottir M, Eriksson LO, Thysell H, Kaskas JD. Plasma concentration profiles of simvastatin 3-hydroxy-3-methyl- glutaryl-coenzime A reductase inhibitory activity in kidney transplant recipients with and without cyclosporin. Nephron. 1993;65:410–413. doi: 10.1159/000187521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michalets EL. Update: clinically significant cytochrome P–450 drug interactions. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:84–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kantola T, Kivisto KT, Neuvonen PJ. Grapefruit juice greatly increases serum concentration of lovastatin and lovastatin acid. Clin Pharmcol Ther. 1998;63:397–402. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lilja JJ, Kivisto KT, Neuvonen PJ. Grapefruit juice– simvastatin interaction: Effects on serum concentration of simvastatin, simvastatin acid, and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Clin Pharmcol Ther. 1998;64:477–483. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmassmann-Suhijar D, Bullingham R, Gasser R, Schmutz J, Haefeli WE. Rhabdomyolysis due to interaction of simvastatin with mibefradil. Lancet. 1998;27:1929–1930. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78613-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azie NE, Craig Brater C, Becker PA, Jones DR, Hall SD. The interaction of diltiazem with lovastatin and pravastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;64:369–377. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abernethy DR, Kaminsky LS, Dickinson TH. Selective inhibition of warfarin metabolism by diltiazem in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Metab. 1991;257:411–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaminsky LS, Zhang ZY. Human P450 metabolism of warfarin. Pharmacol Therapeut. 1997;73:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00140-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guengerich FP, Brian WR, Iwasaki M, Sari MA, Baarnhielm C, Berntsson P. Oxidation of dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and analogues by human liver cytochrome P-450 3A4. J Med Chem. 1991;34:1838–1844. doi: 10.1021/jm00110a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milleri S, Squassante L, Da Ros L. Proceeding of the 23rd International Congress of Internal Medicine. Manila: 1996. Lacidipine at steady-state does not affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodinamics of warfarin. February 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris MJ, Gilbert JD, Hsieh JY, Matuszewsky BK, Ramjit HG, Baynet WF. Determination of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors simvaststin, lovastatin and pravastatin in plasma by gas chromatographic/chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1993;22:1–8. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200220102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braggio S, Sartori S, Angeri F, Pellegatti M. Automation and validation of the high-performance liquid chromatographic- radioimmunoassay method for the determination of lacidipine in plasma. J Chromatogr B. 1995;669:383–389. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(95)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meredith PA. The pharmacokinetics of lacidipine. Rev Contemp Pharmacother. 1995;6:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wrang RW, Kari PH, Lu AYH, Thomas PE, Geengerich FP, Vyas KP. Biotransformation of lovastatin. IV. Identification of cytochrome P450 3A proteins as the mayor enzymes responsible for the oxidative metabolism of lovastatin in rat and human liver microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;290:355–361. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90551-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prueksaritanont T, Gorham LM, Ma B, Liu L, Yu X, Zhao Jj, et al. In vitro metabolism of simvastatin in humans [SBT] identification of metabolizing enzymes and effect of the drug on hepatic P450s. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:1191–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roche withdraws Posicor [editorial] Scrip. 1998;2342:20. June 10. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neuvonen PJ, Jalava KM. Itraconazole drastically increases plasma concentrations of lovastatin and lovastatin acid. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60:54–61. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neuvonen PJ, Kantola T, Kivisto KT. Simvastatin but not pravastatin is very susceptible to interaction with the CYP3A4 inhibitor itraconazole. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;63:332–341. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(98)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Transon C, Leeman T, Vogt N, Dayer P. In vivo inhibition profile of cytochrome P450 (CYP2C9) by (±)-fluvastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1995;58:412–417. doi: 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kivisto KT, Kantola T, Neuvonen PJ. Different effects of itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics of fluvastatin and lovastatin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;46:49–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mück W, Ochhmann K, Rohde G, Unger S, Kuhlmann J. Influence of erythromycin pre- and co-treatment on single-dose pharmacokinetics of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor cerivastatin. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;53:469–473. doi: 10.1007/s002280050408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pierno S, Luca A, Tricarico D, et al. Potential risk of myopathy by HMGCoA reductase inhibitors: a comparison of pravastatin and simvastatin effects on membrane electrical proprieties of rat skeletal muscle fibers. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1490–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jukema JW, van Boven AJ, Zwinderman AH, Van der Laarse A, Bruschke AVG. Proposed synergistic effect of calcium channel blockers with lipid-lowering therapy in retarding progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Drug Ther. 1998;12:111–118. doi: 10.1023/a:1007733311487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cominacini L, Garbin U, Fratta Pasini A, et al. Lacidipine inhibits the activation of the transcription factor NF-kappaB and the expression of adhesion molecules induced by pro-oxidant signals on endotelial cells. J Hypertension. 1997;15:1633–1640. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Physicians' Desk Reference. Medical Economics Company Inc; 1996. pp. 1775–1779. Zocor (simvastatin) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson MH, Stein EA, Dujovne CA, et al. The efficacy and six-week tolerability of simvastatin 80 and 160 mg/day. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:38–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00742-4. 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00742-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stein EA, Davidson MH, Dobs AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of simvastatin 80 mg/day in hypercholesterolemic patients. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:311–316. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00421-4. 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00421-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]