Abstract

Aims

The aims of the present study were to investigate the metabolism of astemizole in human liver microsomes, to assess possible pharmacokinetic drug-interactions with astemizole and to compare its metabolism with terfenadine, a typical H1 receptor antagonist known to be metabolized predominantly by CYP3A4.

Methods

Astemizole or terfenadine were incubated with human liver microsomes or recombinant cytochromes P450 in the absence or presence of chemical inhibitors and antibodies.

Results

Troleandomycin, a CYP3A4 inhibitor, markedly reduced the oxidation of terfenadine (26% of controls) in human liver microsomes, but showed only a marginal inhibition on the oxidation of astemizole (81% of controls). Three metabolites of astemizole were detected in a liver microsomal system, i.e. desmethylastemizole (DES-AST), 6-hydroxyastemizole (6OH-AST) and norastemizole (NOR-AST) at the ratio of 7.4:2.8:1. Experiments with recombinant P450s and antibodies indicate a negligible role for CYP3A4 on the main metabolic route of astemizole, i.e. formation of DES-AST, although CYP3A4 may mediate the relatively minor metabolic routes to 6OH-AST and NOR-AST. Recombinant CYP2D6 catalysed the formation of 6OH-AST and DES-AST. Studies with human liver microsomes, however, suggest a major role for a mono P450 in DES-AST formation.

Conclusions

In contrast to terfenadine, a minor role for CYP3A4 and involvement of multiple P450 isozymes are suggested in the metabolism of astemizole. These differences in P450 isozymes involved in the metabolism of astemizole and terfenadine may associate with distinct pharmacokinetic influences observed with coadministration of drugs metabolized by CYP3A4.

Keywords: astemizole, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, cytochrome P450, human liver microsomes, terfenadine

Introduction

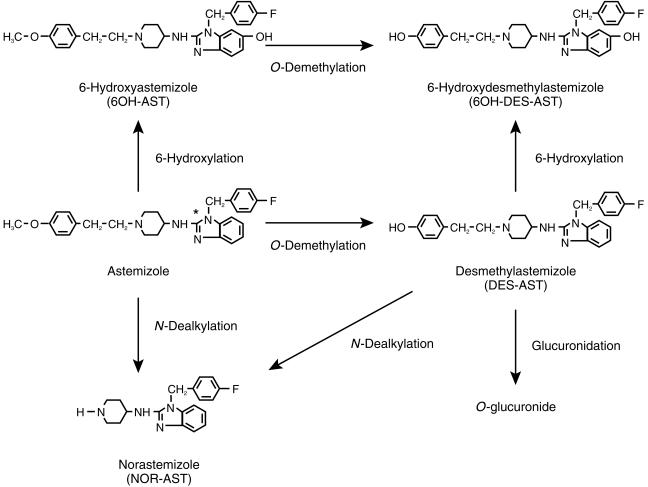

Astemizole {1-(4-fluorophenylmethyl)-N-1-[2-(4-methoxy phenyl)ethyl]-4piperidinyl-1H-benzimidazole-2-amine} is a potent nonsedative H1-receptor antagonist, which is effective for treatment of allergic rhinitis or chronic urticaria [1]. This drug is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and undergoes extensive the first-pass metabolism to a pharmacologically active metabolite, DES-AST, and other metabolites (Figure 1) [2, 3]. Consequently, the AUC of astemizole is approximately 20 times less than that of DES-AST [3].

Figure 1.

Proposed metabolic pathways of astemizole in man. *:[14C] labelled position.

Although most H1-receptor antagonists belonging to so-called ‘second generation’ drugs were developed to have a decreased incidence of sedation, ventricular dysrhythmia has been reported in patients taking these antihistamines in overdose or certain clinical conditions. Moreover, there is concern about the cardiotoxicity of terfenadine and astemizole [4–11]. Terfenadine prolongs the cardiac QT interval and induces the ventricular dysrhythmia, torsades de pointes after overdose or concomitant administration of CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole, itraconazole or erythromycin [7–11]. Astemizole and terfenadine are extensively metabolized in the body and concomitant administration of CYP3A4 inhibitors with astemizole is contraindicated. However, no definite reports are available on the P450 isoforms involved in the metabolism of astemizole.

In the present study, we have investigated the oxidative metabolism of astemizole using human liver microsomes and recombinant P450s to identify the individual forms involved in the metabolism of astemizole. Furthermore, the possibility of CYP3A4-mediated astemizole–drug interaction was investigated in comparison with terfenadine.

Methods

Chemicals

Pooled human liver microsomes were purchased from Human Biologics, Inc. (Phoenix, AZ) and Xenotech LLC. (Cambridge, KS). Individual microsomes (H102 and H112) were prepared from human livers obtained from SRI Internationals (Menlo Park, CA) as described previously [12]. For a correlation study, individual human liver microsomes were obtained from Xenotech LLC (Reaction Phenotyping Kit). These individual microsomes were prepared from 15 donors, which were characterized by the supplier for P450 form activities to exhibit considerable variability between individual microsomal samples in terms of their catalytic activities. Yeast microsomes expressing human CYP1A1, 1A2, 2A6, 2B6, 2C8, 2C9, 2C18, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, or 3A4 were purchased from Sumika Chemical Analysis Service, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Microsomes from human B-lymphoblastoid cell lines expressing human CYP 4A11 were obtained from Gentest Corp. (Woburn, MA). Rabbit anti-rat CYP3A2 sera (anti-CYP3A2 antibody) and anti-CYP2D6 sera (anti-CYP2D6 antibody) were purchased from Daiichi Chemical Co. Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). Astemizole, [14C]-astemizole, 6OH-AST, 5-hydroxyastemizole (5OH-AST), NOR-AST, DES-AST, 6-hydroxydesmethylastemizole (6OH-DES-AST) and 5-hydroxydesmethylastemizole (5OH-DES-AST) (Figure 1) were supplied by Janssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium). The specific activity of [14C]-astemizole was 740 MBq (20 mCi mmol−1). Furafylline and SKF525-A (Research Biochemicals International, Natick, MA), R55248 (Research Diagnostic Inc., Flanders, NJ) and coumarin, quinidine, diethyldithiocarbamate, troleandomycin, terfenadine (Sigma Chemical Co., St Louis, MO) were purchased from the sources indicated. Omeprazole and sulphaphenazole were synthesized by Mochida Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). All other commercially available reagents and solvents were of either analytical or high performance liquid chromatography (h.p.l.c.) grade.

Astemizole metabolism by human liver microsomes and recombinant P450s

The incubation mixture for astemizole metabolism consisted of 1 or 10 µm of [14C]-astemizole, 0.1–0.5 mg ml−1 human liver microsomes, an NADPH-generating system (3.3 mm magnesium chloride, 3.3 mm glucose 6-phosphate, 1.3 mm NADP, 1.0 U ml−1 glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase) and 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a final volume of 0.5–2 ml. The reaction was initiated by addition of the NADPH-generating system after 5 min of preincubation at 37°C and continued for 10–60 min. The reaction was terminated by addition of methanol (four equivalent volumes of the corresponding reaction mixture). The samples were centrifuged at 1800 g for 10 min. The remaining residue was re-extracted by methanol: chloroform (2:1) 1 ml if the recovery of radioactivity in supernatant was less than 90% of the starting value. The supernatant was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure, and resolved in methanol (50 µl). Aliquots of the solution (20 µl) were analysed by h.p.l.c. [14C]-Astemizole was added as a methanolic solution in the reaction mixtures to ensure final methanol concentration as 1%.

Incubation with recombinant P450s was performed similarly to human liver microsomes, except for the differences in amounts of microsomal material. Yeast microsomes contained 100 pmol P450 ml−1 of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C18, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1 or CYP3A4. Microsomes of human B-lymphoblastoid cell lines contained 39 pmol P450 ml−1 of CYP4A11. Recombinant human P450s were incubated with [14C]-astemizole (10 µm) in a final volume of 0.5 ml. The reaction was initiated by addition of microsomes after 5 min of preincubation at 37°C and terminated after 60 min by the addition of four equivalent volumes of methanol. The samples were processed and analysed similarly to human liver microsomes.

Kinetic studies were conducted in the presence of yeast microsomes containing CYP3A4, CYP2D6 or pooled human liver microsomes. All incubations were performed as previously described, except that the concentration of P450 was 5 pmol P450 ml−1 and the concentration of [14C]-astemizole was varied (1–30 µm) in a final volume of 0.5–2 ml. To avoid secondary metabolism, the reaction was terminated after 3 min for yeast microsomes containing CYP3A4, CYP2D6 or 20 min for pooled human liver microsomes. In these conditions, metabolite concentrations increased linearly with the increase in incubation period. The kinetic data were fitted using 4 model rate equations by nonlinear regression using WinNonlin (Scientific Consulting Inc., Version 1.5) to estimate Km and Vmax [13]. Data obtained with human liver microsome were best described by a single enzyme equation 1 for formation of DES-AST and formation of NOR-AST, and a two enzyme equation 2 for formation of 6OH-AST. Data obtained with yeast microsomes were described by a single enzyme equation 1. Goodness of fit was determined using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [14].

| (1) |

| (2) |

Marker activities, phenacetin O-deethylation for CYP1A2 [15], coumarin 7-hydroxylation for CYP2A6 [16], 7-ethoxycoumarin O-deethylation for CYP2B6 [17], tolbutamide hydroxylation for CYP2C9 [15], S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation for CYP2C19 [15], bufuralol 1′-hydroxylation for CYP2D6 [15], chlorzoxazone 6-hydroxylation for CYP2E1 [15], testosterone 6β-hydroxylation for CYP3A4 [15] and lauric acid 12-hydroxylation for CYP4A11 [18], were assessed in human liver microsomes and recombinant P450s. The substrate concentrations used for each assay were 100 µm for phenacetin, coumarin, bufuralol and lauric acid; 200 µm for testosterone; 500 µm for 7-ethoxycoumarin, 500 µm for tolbutamide and chlorzoxazone.

Correlation study

The incubation mixture for a correlation study consisted of 1 µm of [14C]-astemizole, 0.1 mg ml−1 liver microsomes, the NADPH-generating system and 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a final volume of 2 ml. The reaction was initiated by addition of the NADPH-generating system after 5 min of preincubation at 37 °C and continued for 20 min. Under these conditions, metabolites formation was linearly related to the incubation time. The samples were processed and analysed as described above. Correlation coefficients (r) were obtained after linear regression using Stat View (Ver.4, Abacus Concepts, Inc., Barkeley, California). Multiple regression analysis was also conducted using JMP (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, Version 3.2).

Chemical inhibition

SKF525-A (100 µm, 500 µm) was used as general inhibitor for P450 [19], furafylline (50 µm) for CYP1A2 [15], sulphaphenazole (20 µm) for CYP2C9 [15, 19], omeprazole (10 µm) for CYP2C19 [20], quinidine (10 µm) for CYP2D6 [15, 19], diethyldithiocarbamate (20 µm) for CYP2E1 [21] and troleandomycin (10–200 µm) for CYP3A4 [15]. Coumarin, a specific substrate of CYP2A6 [22, 23], was used as the competitive inhibitor (500 µm).

The incubation mixture consisted of [14C]-astemizole (1 µm), inhibitor, 0.1 mg ml−1 human liver microsomes (HBI pool94, H102 and H112), the NADPH-generating system and 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a final volume of 2 ml. The reaction was initiated by addition of the NADPH-generating system after 5 min of preincubation at 37 °C and continued for 20 min. Mechanism-based inhibitors, SKF525-A, furafylline, diethyldithiocarbamate and troleandomycin, were incubated with human liver microsomes and the NADPH-generating system for 15 min at 37 °C, then the reaction was initiated by the addition of [14C]-astemizole. The samples were processed and analysed as described above. Under these conditions, the formation of metabolites was linearly related to incubation time. [14C]-Astemizole and chemical inhibitors were dissolved in methanol to achieve a final concentration of methanol in the reaction mixture of 1%.

A CYP3A4 inhibitor, troleandomycin, was used to assess CYP3A4-related astemizole drug–drug interactions. In the experiment, the effect of troleandomycin on total astemizole and terfenadine oxidation was evaluated in the presence of pooled human liver microsomes. The incubation mixture consisted of troleandomycin (10–200 µm), 0.5 mg ml−1 human liver microsomes (pool of 15, High 3 A and Low 3 A), the NADPH-generating system and 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) in a final volume of 0.5 ml. The reaction was initiated by addition of substrate (astemizole: 1 µm, terfenadine: 5 µm) after 15 min of preincubation at 37 °C and continued for 5–60 min.

Astemizole metabolism was terminated by addition of 1 ml heptane: isoamylalchol (95:5). After addition of 0.5 ml of 0.05 mm borax and 0.05 ml of 0.05 mg ml−1 R55248 (internal standard), astemizole was extracted twice with heptane: isoamylalchol (95:5), evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure, and then redissolved in 100 µl h.p.l.c. mobile phase. Aliquots of the solution (50 µl) were subjected to h.p.l.c. Terfenadine metabolism was terminated by addition of 1 ml ethylacetate. Following extraction twice with 1 ml ethylacetate, the supernatant was evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure, and then resolved in 100 µl h.p.l.c. mobile phase. Aliquots of the solution (50 µl) were subjected to h.p.l.c.

Immunoinhibition

Immunoinhibition experiments were conducted by incubation of anti-P450 immunoglobulin G obtained from rabbit with pooled human liver microsomes at room temperature for 30 min. The reaction was started by the addition of [14C]-astemizole (10 µm), the NADPH-generating system and 100 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and continued for 30–60 min. The samples were processed and analysed as described previously. Inhibitory potency of antibodies to P450 marker activities, testosterone 6β-hydroxylation and bufuralol 1′-hydroxylation, were examined by using the experimental protocol similar to that described above.

H.p.l.c. conditions

A radiochemical-h.p.l.c. analysis was performed using a Jasco 800 series instrument, which included a model 800 pump, a model 800 absorbance detector (285 nm). Samples were separated at 40 °C in a reversed-phase mode using a Inertsil ODS-2 (5 µm, 250×4.6 mm i.d., GL Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of multiple gradients of solvent A (acetonitrile) and solvent B (20 mm sodium acetate buffer, pH 5) or solvent C (20 mm ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5). After an injection of the sample, a linear gradient was started from A:B or C = 15:85–80:20 over a period of 33 min at the flow rate of 1.0 ml min−1. Radioactivity in the column eluent was monitored with a Flo-One β using Flo-Scinti (Packard Instrument Co., Meriden, CT) as the scintillator at a flow rate of 3.0 ml min−1. H.p.l.c. analyses of astemizole and terfenadine were performed using a Waters 600 series system, which included a model 616 pump, a model 717 autosampler. Separations of astemizole were accomplished at 40 °C in a reversed-phase mode using Capcellpak C8 SG120 (5 µm, 250×4.6 mm i.d., Shiseido, Tokyo, Japan). A Jasco Model UV-970 intelligent UV/VIS detector was used at 283 nm for the detection of astemizole. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile-20 mm sodium acetate (pH 5) containing 0.1% diethylamine in the proportions 37:63. The flow rate was set at 1.0 ml min−1. Separations of terfenadine were accomplished at 40 in a reversed-phase mode using Develosil ODS HG-5 (5 µm, 150×4.6 mm i.d., Nomura chemical, Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). A Jasco Model 820-FP intelligent fluorescent spectrophotometer was used with settings of 230 nm excitation and 280 nm emission for terfenadine detection. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile-10 mm ammonium acetate (pH 4) in the proportions 40:60. The flow rate was set at 1.0 ml min−1.

Results

Metabolism of astemizole by human liver microsomes

Oxidative metabolism of astemizole was examined using pooled human liver microsomes in the presence of 1 or 10 µm [14C]-astemizole. [14C]-Astemizole was converted primarily into three metabolites identified as DES-AST (O-demethylated), 6OH-AST (6-hydroxylated) and NOR-AST (N-dealkylated) by comparison with the authentic samples.

Correlation studies with P450 isoform-selective marker activities

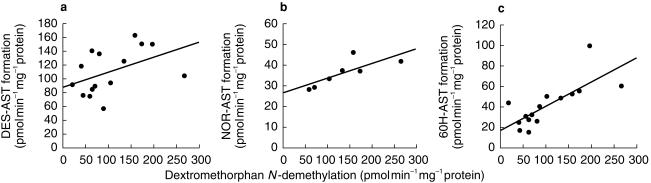

To identify P450 isoforms involved in astemizole metabolism, the rates of astemizole metabolism at the 1 µm was compared with metabolic rates of P450 isoform-selective markers using microsomes from 15 different human livers (Table 1; Figure 2).

Table 1.

Regression analysis of various P450 isoform-selective marker activities with astemizole metabolism in a panel of human liver microsomes.

| Correlation coefficient (r) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction | P450 isoform | DES-AST formationa | NOR-AST formationb | 6OH-AST formationca |

| 7-Ethoxyresorufin O-dealkylation | CYP1A2 | 0.067 | 0.199 | 0.202 |

| Coumarin 7-hydroxylation | CYP2A6 | 0.169 | 0.545 | 0.025 |

| 7-Ethoxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin deethylation | CYP2B6 | 0.215 | 0.496 | 0.273 |

| Taxol 6-hydroxylation | CYP2C8 | 0.241 | 0.207 | 0.293 |

| Tolbutamide hydroxylation | CYP2C9 | 0.183 | −0.091 | 0.025 |

| S-Mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation | CYP2C19 | 0.291 | 0.225 | −0.149 |

| Dextromethorphan O-demethylation | CYP2D6 | 0.086 | 0.275 | −0.039 |

| Chlorozoxazone 6-hydroxylation | CYP2E1 | 0.130 | −0.190 | 0.450 |

| Testosterone 6β-hydroxylation | CYP3A4/5 | 0.470 | 0.577 | 0.884** |

| Dextromethorphan N-demethylation | CYP3A4 | 0.459 | 0.785* | 0.756** |

| Lauric acid 12-hydroxylation | CYP4A11 | −0.013 | −0.321 | −0.113 |

a) Correlation coefficient was determined with the liver tissue of 15 different organ donor subjects, except for correlation involving 7-ethoxy-4-trifluoromethylcoumarin deethylation (n = 14). b) Correlation coefficient was determined with the liver tissue of seven different organ donor subjects. The statistical significance of the correlation is denoted by

P < 0.05

P < 0.01. Astemizole (1 µm) was incubated with human liver microsomes (0.1 mg ml−1) and an NADPH-generating system for 20 min at 37°C.

Figure 2.

Simple regression analysis of dextromethorphan N-demethylation and the rates of DES-AST formation (a), NOR-AST formation (b) and 6OH-AST formation (c).(a) y = 0.217 x + 87.6, r = 0.459, n = 15; (b) y = 0.071 x + 26.5, r = 0.785, P < 0.05, n = 7; y = 0.237 x + 16.9, r = 0.756, P < 0.01, n = 15.

The rate of DES-AST formation varied from 56.8 to 163.0 pmol min−1 mg−1 protein (2.9-fold, 673% of total astemizole metabolism, mean±s.e.mean of 15 samples, 50–91%). There was no clear correlation with any of 13 different marker activities listed in Table 1. Data were analysed further by multiple regression. Although a combination of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 showed best correlation, the result of this analysis was not significant (The rate of DES-AST formation=(0.22×dextromethorphan N-demethylation) + (0.15×S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation) + 76.59; P = 0.116). Addition of dextromethorphan O-demethylation to the model did not give any improvement.

The rate of 6OH-AST formation varied from 14.6 to 99.7 pmol min−1 mg−1 protein (6.8-fold, 25±2% of total astemizole metabolism, mean±s.e. mean of 15 samples, 9–42%) and correlated significantly with both dextromethorphan N-demethylation (r = 0.756, P < 0.01) and testosterone 6β-hydroxylation (r = 0.884, P < 0.01).

The rate of NOR-AST formation was low, and detectable only in seven out of 15 samples (Not detectable: < 16.6 pmol min−1 mg−1 protein). Within the seven samples, variation was relatively small (28.4–46.2 pmol min−1 mg−1 protein, 1.6-fold, 9±3% of total astemizole metabolism, mean±s.e. mean of 15 samples, 0–21%), and correlated significantly with the dextromethorphan N-demethylation (r = 0.785, P < 0.05). In addition, the rate of NOR-AST formation showed relatively poorer correlation with testosterone 6β-hydroxylation (r = 0.577) or coumarin 7-hydroxylation (r = 0.545).

Metabolism of astemizole by recombinant P450s

To identify P450 isoforms mediating the metabolism of astemizole, 12 different recombinant P450s were used (Table 2). Among them, only CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 showed clear astemizole metabolizing activities. The remainder (CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C18, CYP2C19, CYP2E1 and CYP4A11) metabolized their respective marker substrates, but not astemizole. In the recombinant CYP3A4 systems, NOR-AST was formed at the rate of 4.6 nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1. 6OH-AST was also formed at the rate of 3.6 nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1, whereas CYP3A4 showed no activity for DES-AST formation (< 2 nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1). CYP2D6 also metabolized astemizole to both 6OH-AST and DES-AST. The rate of formation of 6OH-AST was 26.5 nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1. The rate of DES-AST formation was 8.1 nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1. By contrast, no NOR-AST was detected with recombinant CYP2D6 (< 2 nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1). The ratio of the rate of DES-AST formation to that of 6OH-AST formation in these system was 1:3.3, compared with the ratio of 2.7:1 obtained with human liver microsomes.

Table 2.

Astemizole metabolism in recombinant P450s.

| P450 form | DES-AST formation | NOR-AST formation | 6OH-AST formation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A1 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP1A2 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP2A6 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP2B6 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP2C8 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP2C9 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP2C18 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP2C19 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP2D6 | 8.1 | ND | 26.5 |

| CYP2E1 | ND | ND | ND |

| CYP3A4 | ND | 4.6 | 3.6 |

| CYP4A11 | ND | ND | ND |

Metabolite formation rate using microsomes from yeast cell expressing each P450 isoform were shown except for CYP4A11. 10 µm[14C]-astemizole was incubated for 60 min with 100 pmol ml−1 of microsomes from yeast cell expressing each P450 isoform. Not detectable (ND): <2 nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1. For CYP4A11, 10 µm[14C]-astemizole was incubated for 60 min with 39 pmol ml−1 of microsomes from lymphoblastoid cell expressing CYP4A11 (ND: <5.1 nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1). Values are expressed as nmol nmol−1 P450 60 min−1.

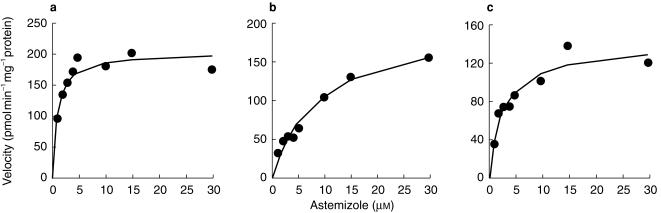

To characterise further the metabolism of astemizole, apparent kinetic parameters were determined using recombinant CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 in yeast or pooled human liver microsomes (Figure 3; Table 3). The apparent Km of NOR-AST formation was 30.0 µm in recombinant CYP3A4 and 9.2 µm in pooled human liver microsomes. Both CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 showed high affinities for 6OH-AST formation (Km: 0.96 µm and 9.8 µm, respectively). These values were consistent with those obtained with pooled human liver microsomes (Km1: 1.0 µm, Km2: 3.9 µm). The apparent Km value for DES-AST formation was also low (0.82 µm) with recombinant CYP2D6, and compatible with that obtained with pooled human liver microsomes (0.94 µm).

Figure 3.

S–V plot for astemizole metabolism in human liver microsomes. Liver samples HBI pool 94 were used. Astemizole (1–30 µm) was incubated for 20 min with human liver microsome. • Observed data, solid lines: fitted curves. (a) DES-AST formation, (b) NOR-AST formation, (c) 6OH-AST formation.

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters of astemizole metabolism by human liver microsome and recombinant CYP3A4 or CYP2D6

| Reactions | Enzyme | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DES-AST formation | Human liver microsome | 0.94 | 203 | ||

| cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 | 0.82 | 7.7 | |||

| NOR-AST formation | Human liver microsome | 9.2 | 203 | ||

| cDNA-expressed CYP3A4 | 30.0 | 16.1 | |||

| 6OH-AST formation | Human liver microsome | 1.0 (Km1) | 33.5(Vmax1) | ||

| 3.9 (Km2) | 109 (Vmax2) | ||||

| cDNA-expressed CYP3A4 | 9.8 | 7.5 | |||

| cDNA-expressed CYP2D6 | 0.96 | 12.0 |

a) μm, b) pmol min−1 mg−1 protein for human liver microsome and nmol min−1 nmol−1 P450 for recombinant P450 systems.

Chemical inhibition

Astemizole oxidation was examined with hepatic pooled microsomes in the presence of SKF525-A. SKF525-A inhibited total microsomal astemizole oxidation in a concentration-dependent manner. Values were reduced to 35% and 5% of control at 100 µm and 500 µm, respectively. 6OH-AST formation was also decreased to 23% and < 10% (ND) of controls, NOR-AST formation to 23% and < 10% (ND) of controls and DES-AST formation to 52% and 17% of controls at 100 µm and 500 µm, respectively.

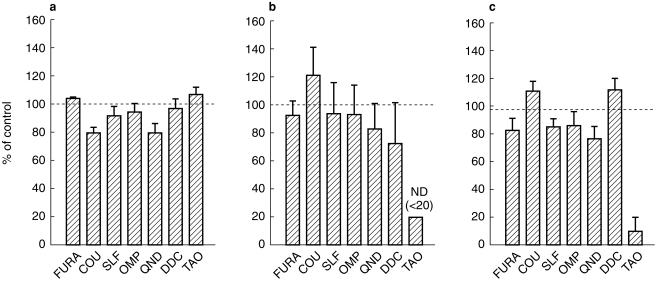

The effects of seven different inhibitors on the production of individual astemizole metabolites are shown in Figure 4. Among the agents tested, troleandomycin (100 µm) showed the strongest inhibition, which reduced NOR-AST formation and 6OH-AST formation to < 20% (ND) and 10% of the controls, respectively. Troleandomycin showed no inhibitory effect on DES-AST formation. Other inhibitors (furafylline: 50 µm, coumarin: 500 µm, sulphaphenazole: 20 µm, omeprazole: 10 µm, quinidine: 10 µm, diethyldithiocarbamate: 20 µm) showed little (< 30%) or no inhibitory effect on all three reactions.

Figure 4.

Effects of P450 isoform-selective inhibitors on [14C]-astemizole metabolism by human liver microsomes. Liver samples HBI pool 94, H102 and H112 were used. FURA: furafylline (50 µm), COU: coumarin (500 µm), SLF: sulphaphenazole (20 µm), OMP: omeprazole (10 µm), QND: quinidine (10 µm), DDC: diethyldithiocarbamate (20 µm), TAO: troleandomycin (100 µm). FURA, DDC and TAO was preincubated in the presence of human liver microsomes and an NADPH-generating system for 15 min at 37 °C. Data are expressed as percentage activity remaining relative to a control (methanol alone) incubation and represented as mean±s.e. mean. ND: < 20%. (a) DES-AST formation, (b) NOR-AST formation, (c) 6OH-AST formation.

Immunoinhibition

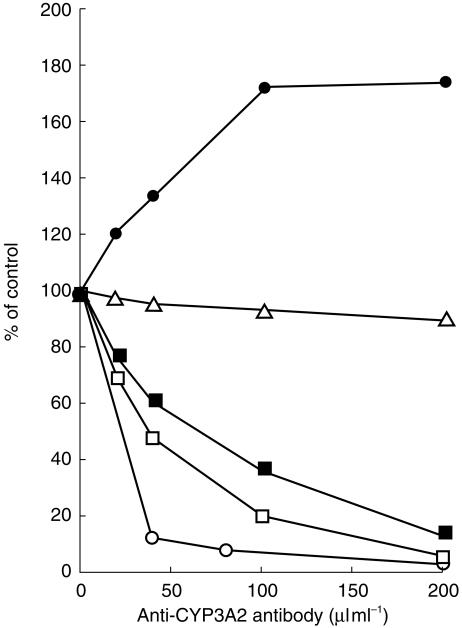

To assess further the role of CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 in the metabolism of astemizole, the effect of polyclonal antibodies on astemizole oxidation was examined using anti-CYP3A2 antibody and anti-CYP2D6 antibody, which cross-reacted with CYP3A4 and CYP2D6, respectively. As shown in Figure 5, microsomal testosterone 6β-hydroxylation was reduced to 10% of control by the addition of 200 µl ml−1 of anti-CYP3A2 antibody, whereas no clear inhibition was observed on total microsomal astemizole metabolism up to 200 µl ml−1. For individual astemizole metabolic pathways, the addition of anti-CYP3A2 antibody reduced both the formation of NOR-AST and 6OH-AST in human liver microsomes in concentration-dependent manners. By contrast, the addition of anti-CYP3A2 antibody appeared to increase DES-AST formation.

Figure 5.

Effects of anti-CYP3A2 antibody on [14C]-astemizole metabolism by human liver microsomes. Pooled human liver microsomes (HBI pool 94) was used, with preincubation with anti-CYP3A2 antibody for 30 min at room temperature. Data were expressed as percentage activity remaining relative to a control (preimmunoglobulin) incubation. Control activity: astemizole metabolism: 282.5, DES-AST formation: 125.2, NOR-AST formation: 57.0, 6OH-AST formation: 23.5 pmol min−1 mg−1 protein. Limit of detection: 3.2 pmol min−1 mg−1 protein. Astemizole metabolism (▵), DES-AST formation (•), NOR-AST formation (□), 6OH-formation (▪), testosterone 6β-hydroxylation (○).

Microsomal bufuralol 1′-hydroxylation was decreased to 30% of controls by the addition of anti-CYP2D6 antibody at 200 µl ml−1. 6OH-AST formation was slightly decreased (85% of controls at 200 µl ml−1), although DES-AST formation and NOR-AST formation were not affected by the addition of anti-CYP2D6 antibody.

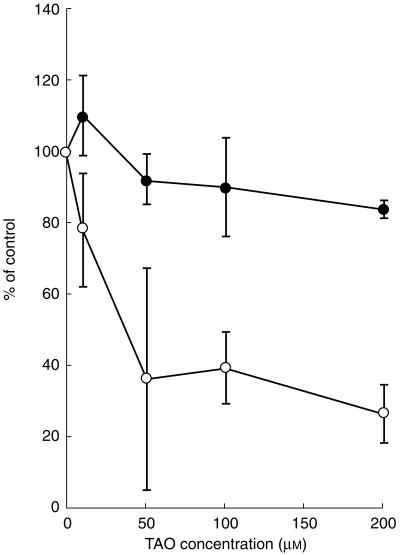

Effect of troleandomycin on astemizole and terfenadine metabolism

To evaluate CYP3A4-related drug–drug interactions with astemizole, the inhibition of astemizole metabolism by troleandomycin was compared with terfenadine (Figure 6). In control incubations, 31±5% (mean±s.e. mean, n = 3) of astemizole, 48±18% of terfenadine were metabolized. Troleandomycin inhibited total microsomal terfenadine oxidation in a concentration-dependent manner to 26±5% of controls at 200 µm. Troleandomycin marginally reduced total microsomal astemizole oxidation (81±1% of control values) at 200 µm.

Figure 6.

Effect of troleandomycin on astemizole and terfenadine metabolism by human liver microsomes. Three pooled human liver microsomes were used. troleandomycin (10–200 µm) was preincubated in the presence of human liver microsomes and an NADPH-generating system for 15 min at 37 °C. Data are expressed as percentage activity remaining relative to a control (methanol alone) incubation and represented as mean±s.e. mean of three samples. In control incubations, 31±5% of astemizole and 48±18% of terfenadine were metabolized during 5–60 min. Astemizole (•), terfenadine (○).

Discussion

Astemizole and terfenadine show clear differences in their dependency on CYP3A4. Microsomal oxidation of terfenadine was inhibited by troleandomycin in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas astemizole oxidation was refractory to the effects of troleandomycin and 81% of the control activity remained at 200 µm. In addition, addition of anti-CYP3A2 antibody clearly inhibited microsomal testosterone 6β-hydroxylation, but did not alter total astemizole oxidation. Terfenadine is metabolized mainly by CYP3A4 [24–28], while multiple isoforms of P450 are involved in the metabolism of astemizole. Therefore, the rate of astemizole metabolism is less influenced by inhibitors of CYP3A4. [14C]-Astemizole was converted primarily into DES-AST (67±3%), 6OH-AST (25±2%) and NOR-AST (9±3%) in the presence of human liver microsomes. CYP3A4 is involved in the latter two relatively minor metabolic routes. Both the rates of 6OH-AST and NOR-AST formation correlate with those of testosterone 6β-hydroxylation and also dextromethorphan N-demethylation. Using 12 different recombinant P450s, CYP3A4 metabolized astemizole to 6OH-AST and NOR-AST. The apparent Km values in a recombinant CYP3A4 system were roughly consistent with the values obtained from pooled human liver microsomes and troleandomycin markedly inhibited both the reactions. While anti-CYP3A2 antibody strongly inhibited both reactions, no clear correlation was obtained between CYP3A4 activities and DES-AST formation, the major metabolic route of astemizole. These results strongly suggest a relatively minor role for CYP3A4 in the metabolism of astemizole. Therefore the rate of astemizole metabolism is less influenced in the presence of CYP3A4 inhibitor.

CYP2D6 may mediate 6OH-AST formation. Recombinant CYP2D6 catalysed the reaction and the apparent Km value was similar to that obtained from pooled human liver microsomes. These findings suggest that CYP2D6 may also be involved in 6OH-AST formation. The rate of 6OH-AST formation in human liver microsomes was not, however, correlated with dextromethorphan O-demethylation, a marker of CYP2D6 activity and the CYP2D6 inhibitor, quinidine inhibited the reaction only marginally in human liver microsomes. Anti-CYP2D6 antibody was largely ineffective. In human livers, microsomal contents of these two P450 isoforms is shown to be higher with CYP3A4 than with CYP2D6 [29]. We suggest therefore a major role of CYP3A4 and a minor role for CYP2D6 in the formation of 6OH-AST.

DES-AST was formed only by recombinant CYP2D6 among 12 recombinant P450 systems. The apparent Km value, obtained from the recombinant CYP2D6 system, was comparable with that obtained from pooled human liver microsomes. Dextromethorphan O-demethylation in human liver microsomes was, however, not correlated with the rate of DES-AST formation. Both quinidine and anti-CYP2D6 antibody also did not inhibit the rate of DES-AST formation in the presence of human liver microsomes, although anti-CYP2D6 antibody markedly inhibited the 1′-hydroxylation of bufuralol. The formation ratio of DES-AST/6OH-AST also differed between recombinant CYP2D6 (1:3.3) and human liver microsomes (2.7:1). These discrepancies might suggest the involvement of another or yet unknown enzyme in the formation of DES-AST although a relatively minor role for CYP2D6 can not be excluded.

In conclusion, drug interactions involving CYP3A4-catalysed astemizole metabolism are not expected to have a major, clinically significant effect on its pharmacokinetics. In contrast to terfenadine, there are few data published on coadministration of astemizole and drugs affecting CYP3A4 activity in humans. Grapefruit juice did not affect astemizole plasma concentrations [30], confirming a minor contribution of CYP3A4 in presystemic drug interaction. Chronic administration of itraconazole, however, increased the AUC and the t½ after single dose of astemizole [31]. In human liver microsomes, ketoconazole inhibits astemizole metabolism with an IC50 of 2.4 µm while itraconazole inhibits astemizole metabolism with a decreased potency (30% inhibition at 30 µm) [32]. Ketoconazole potently inhibits CYP3A4 activity as well as activities mediated by other P450 isoforms [19]. Itraconazole also inhibits CYP3A4 activity while its influence on activities mediated by other P450 forms is unclear [33]. Thus itraconazole may inhibit P450 activities mediated by P450s other than CYP3A4 or a metabolite of itraconazole may inhibit the metabolism of astemizole [34]. However, it is not yet clear whether DES-AST also contributes to the cardiotoxicity of astemizole [35]. Therefore further studies of the metabolism of DES-AST will be necessary to predict pharmacokinetic drug interactions.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nobuo Ohzawa, Kei-ichi Ida, Takanori Watanabe and Tomoko Takahashi (Mochida Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd) for valuable suggestions and assistance.

References

- 1.Richards DM, Brogden RN, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Astemizole, a review of its pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1984;28:38–61. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198428010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meuldermans W, Hendrickx J, Lauwers W, Hurkmans R, Swysen E, Heykants J. Excretion and biotransformation of astemizole in rats, guinea-pigs, dogs, and man. Drug Dev Res. 1986;8:37–51. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heykants J, Peer AV, Woestenborghs R, Jageneau A, Bussche GV. Dose-proportionality, bioavailability, and steady-state kinetics of astemizole in man. Drug Dev Res. 1986;8:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark A, Love H. Astemizole–induced ventricular arrhythmias: an unexpected cause of convulsion. Int J Cardiol. 1991;33:165–167. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(91)90166-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nightingale SL. Warning issued on non-sedating antihistamines terfenadine and astemizole. JAMA. 1992;268:705. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Passalacqua G, Bousquet J, Bachert C, et al. The clinical safety of H1-receptor antagonists. An EAACI position paper. Allergy. 1996;51:666–675. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1996.tb02109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monahan BP, Ferguson CL, Killeavy ES, Lloyd BK, Troy J, Cantilena LR. Torsades de pointes occurring in association with terfenadine use. JAMA. 1990;264:2788–2790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honig PK, Woosley RL, Zamani K, Conner DP, Cantilena LR. Changes in pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic pharmacodynamic of terfenadine with concomitant administration of erythromycin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;52:231–238. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Honig PK, Wortham DC, Zamani K, Conner DP, Mullin JC, Cantilena LR. Terfenadine–ketoconazole interaction. Pharmacokinetic and electrocardiographic consequences. JAMA. 1993;269:1513–1518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honig PK, Wortham DC, Hull R, Zamani K, Smith JE, Cantilena LR. Itraconazole affects single-dose terfenadine pharmacokinetics and cardiac repolarization pharmacodynamics. J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;33:1201–1206. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb03920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pohjola-Sintonen S, Viitasalo M, Toivonen L, Neuvonen P. Itraconazole prevents terfenadine metabolism and increases risk of torsades de pointes ventricular tachycardia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;45:191–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00315505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawano S, Kamataki T, Yasumori T, Yamazoe Y, Kato R. Purification of human liver cytochrome P-450 catalyzing testosterone 6β-hydroxylation. J Biochem. 1987;102:493–501. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwatsubo T, Suzuki H, Sugiyama Y. Prediction of species differences (rats, dogs, humans) in the in vivo metabolic clearance of YM796 by the liver from in vitro data. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:462–469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akaike H. Fitting autoregressive models for prediction. Ann Inst Stat Math. 1969;21:243–247. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newton DR, Wang RW, Lu AYH. Cytochrome P450 inhibitors. Evaluation of specificities in the in vitro metabolism of therapeutic agents by human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:154–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearce R, Greenway D, Parkinson A. Species differences and interindividual variation in liver microsomal cytochrome P450 2A enzymes: effects on coumarin, dicumarol, and testosterone oxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:211–225. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90115-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenlee WF, Poland A. An improved assay of 7-ethoxycoumarin O-deethylase activity: induction of hepatic enzyme activity in C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice by phenobarbital, 3-methylcholanthrene and 2, 3, 7, 8,–tetrachlorodibenzo–p–dioxin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;205:596–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada J, Sakuma M, Suga T. Assay of fatty acid ω-hydroxylation using high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence labeling reagent, 3-bromomethyl-7-methoxy-1, 4-benzoxazin-2-one (BrMB) Anal Biochem. 1991;199:132–136. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(91)90280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono S, Hatanaka T, Hotta H, Satoh T, Gonzalez FJ, Tsutsui M. Specificity of substrate and inhibitor probes for cytochrome P450s: evaluation of in vitro metabolism using cDNA-expressed human P450s and human liver microsomes. Xenobiotica. 1996;26:681–693. doi: 10.3109/00498259609046742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ko JW, Sukhova N, Thacker D, Chen P, Flockhart DA. Evaluation of omeprazole and lansoprazole as inhibitors of cytochrome P450 isoforms. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:853–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eagling VA, Tjia JF, Back DJ. Differential selectivity of cytochrome P450 inhibitors against four probe substrates in human and rat liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;42:673. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00679.x. P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez-Salguero P, Gonzalez FJ. The CYP2A gene subfamily: species differences, regulation, catalytic activities and role in chemical carcinogenesis. Pharmacogenetics. 1995;5:S123–S128. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199512001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Torchin CD, McNeilly PJ, Kapetanovic IM, Strong JM, Kupferberg HJ. Stereoselective metabolism of a new anticonvulsant drug candidate, losigamone, by human liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996;24:1002–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garteiz DA, Hook RH, Walker BJ, Okerholm RA. Pharmacokinetics and biotransformation studies of terfenadine in man. Arzneim Forsch Drug Res. 1982;32:1185–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun CH, Okerholm RA, Guengerich FP. Oxidation of the antihistamine drug terfenadine in human liver microsomes. Role of cytochrome P 4503A in N-dealkylation and C-hydroxylation. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jurima-Romet M, Crawford K, Cyr T, Inaba T. Terfenadine metabolism in human liver. In vitro inhibition by macrolide antibiotics and azole antifungals. Drug Metab Dispos. 1994;22:849–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Duan SX, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. In vitro prediction of the terfenadine–ketoconazole pharmacokinetic interaction. J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;34:1222–1227. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1994.tb04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ling KHJ, Leeson GA, Burmaster SD, Hook RH, Reith MK, Cheng LK. Metabolism of terfenadine associated with CYP3A (4) activity in human hepatic microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 1995;23:631–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada T, Yamazaki H, Mimura M, Inui Y, Guengerich FP. Interindividual variations in human liver cytochrome P-450 enzymes involved in the oxidation of drugs, carcinogens and toxic chemicals: studies with liver microsomes of 30 Japanese and 30 Caucasians. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:414–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spence JD. Drug interactions with grapefruit: Whose responsibility is it to warn the public ? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;61:395–400. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90189-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lefebvre RA, Peer VA, Woestenborghs R. Influence of itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics and electrocardiographic effects of astemizole. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43:319–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00548.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavrijsen K, Van Houdt J, Meuldermans W, Janssens M, Heykants J. The interaction of ketoconazole, itraconazole and erythromycin with the in vitro metabolism of antihistamines in human liver microsomes. Allergy. 1993;48:34. Suppl. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McKillop D, Back DJ, McCormick AD, Evans JA, Tjia J. Preclinical and in vitro assessment of the potential of D0870, an antifungal agent, for producing clinical drug interactions. Xenobiotica. 1999;29:395–408. doi: 10.1080/004982599238579. 10.1080/004982599238579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heykants J, Van Peer A, Van de Velde V, et al. The clinical pharmacokinetics of itraconazole: an overview. Mycoses. 1989;32(Suppl 1):67–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1989.tb02296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vorperian VR, Zhou Z, Mohammad S, Hoon TJ, Studenik C, January CT. Torsade de pointes with an antihistamine metabolite: potassium channel blockade with desmethylastemizole. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1556–1561. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00352-x. 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00352-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]