Abstract

Aims

To investigate the peripheral vascular effects and pharmacokinetics of dihydroergotamine (DHE) 0.5 mg after a single subcutaneous administration in humans.

Methods

A double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study was performed in 10 healthy male subjects. A wash-out period of 2 weeks separated the two study periods. During each period, just before and at regular intervals after drug administration, vascular measurements were performed and venous blood samples were drawn. Vessel wall properties were assessed at the brachial artery, by ultrasound and applanation tonometry. Blood pressure and heart rate were recorded with an oscillometric device. Forearm blood flow was measured with venous occlusion plethysmography. For all parameter-time curves the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated. Differences in AUC after placebo and DHE (ΔAUC) were analysed and the time-course of the difference assessed. DHE pharmacokinetics were analysed according to a two-compartment open model with an absorption phase.

Results

AUC for blood pressure, heart rate and forearm vascular resistance did not change after DHE. Brachial artery diameter and compliance decreased (P < 0.01); ΔAUC (95% confidence interval) equalled −8.81 mm h (−12.97/−4.65) and −0.98 mm2 kPa−1 h (−1.61/−0.34), respectively. Diameter decreased (P < 0.05) from 1 until 24 h after DHE (peak decrease 9.7% at 10 h); compliance from 2 until 32 h (24.8% at 2 h). Time to reach maximum plasma concentration of DHE averaged 0.33 ± 0.08 h (± s.e.mean); terminal half-life was 5.63 ± 1.15 h.

Conclusions

DHE decreased diameter and compliance of the brachial artery whereas forearm vascular resistance remained unchanged. Thus, DHE acts on conduit arteries without affecting resistance arteries. Furthermore, a discrepancy was demonstrated between the plasma concentrations of DHE which rapidly reach peak levels and quickly decline, and its long lasting vasoconstrictor activity.

Keywords: arterial, arteriolar, dihydroergotamine, pharmacokinetics-human

Introduction

Migraine is a common and debilitating neurological disorder for which effective and safe treatment is needed. The ergot alkaloids ergotamine and dihydroergotamine (DHE) were the first compounds reported to be successful in the acute treatment of migraine [1]. Ergotamine was isolated in 1918 from the fungus Claviceps purpurea and reported effective as an antimigraine drug in 1926. However, because of its unfavourable side-effect profile the dihydrogenated derivative DHE was developed [2]. DHE differs form ergotamine in that it is less toxic, less emetic, devoid of uterotonic activity and it displays a decreased peripheral vasoconstrictor activity [2]. In particular, DHE preferentially constricts venous capacitance vessels and arteriovenous anastomoses while being a much less potent arterial vasoconstrictor [3, 4]. However, it is not entirely clear how this vascular selectivity is obtained as both drugs are nonselective pharmacological agents interacting with serotonergic (5-HT1 and 5-HT2-receptors), adrenergic (α1 and α2-receptors) and dopaminergic receptors (D2-receptors) [2].

The venoconstrictor activity of DHE has been investigated extensively whereas data on its arterial and arteriolar effects are limited. Both in animals [5] and in humans [6–8] a discrepancy has been reported between the long lasting venoconstrictor activity of DHE and its plasma concentration profile showing rapidly increasing plasma levels which quickly decline. With respect to arterial effects, in vitro data show that ergotamine and DHE induce a sustained contraction of human arteries [9, 10]. For ergotamine both long lasting arterial contractions and a discrepancy between plasma concentrations and arterioconstrictor activity have also been reported in human [11]. In contrast, based on indirect measurements Andersen et al. [12] concluded that DHE lacks peripheral arterial effects. Direct assessments of the arterial effects of DHE have never been performed in humans.

These conflicting results between in vitro and in vivo data and the unexpected difference between the vascular effects of ergotamine and DHE, led us to investigate the vascular effects of DHE in vivo in humans. Moreover, as the use of DHE in the acute treatment of migraine can be expected to increase because of the commercial availability of a nasal spray, a better knowledge of its vascular effects is warranted. In the present study, the peripheral vascular effects (arterial and arteriolar) of DHE over time and the time-course of DHE plasma concentrations were investigated simultaneously after the administration of a single subcutaneous injection of DHE to healthy subjects.

Methods

Subjects and study design

Ten nonsmoking, male subjects (age 23 ± 2 years (mean ±s.d.), weight 72 ± 8 kg and height 182 ± 7 cm) entered and completed the study. Based on their medical history, clinical examination, routine laboratory tests and electrocardiogram all subjects were in good health. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the academic hospital of Maastricht and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Hong Kong revision 1989). All patients gave written informed consent to participate.

A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, two-way cross-over design was used. A wash-out period of at least 2 weeks separated the two study periods. During one period dihydroergotamine mesylate (Dihydergot®, Novartis Pharma, 1 mg ml−1) was administered at a dose of 0.5 mg, during the other period 0.5 ml NaCl 0.9% as placebo. Both were administered subcutaneously at the level of the thigh. On each occasion the drug was administered after overnight fasting and subjects remained fasting until 4 h after drug administration. Before drug administration, subjects were asked to abstain from alcohol-containing beverages for at least 24 h. Until all measurements had been performed (i.e. 32 h after drug administration) alcohol and caffeine-containing beverages were not allowed.

Pharmacodynamic assessments

All measurements were performed by one investigator in a quiet room with the subject lying comfortably in the supine position for at least 15 min before measurements were started. Just before (0 h) and at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 24 and 32 h after drug administration, pharmacodynamic assessments were performed. These consisted of noninvasive measurements of (i) vessel wall movements and pressure wave recordings of the brachial artery, (ii) forearm blood flow with and without wrist occlusion and (iii) blood pressure and heart rate.

Brachial artery vessel wall movements

Arterial end diastolic diameter (D) and diameter changes (ΔD, distension) of the right brachial artery were measured using a vessel wall movement detector system as described by Hoeks et al. [13] (Wall Track System®, Pie Medical, The Netherlands). The system makes use of an ultrasound device (Scanner 350, Pie Medical, The Netherlands) equipped with a 7.5-MHz linear-array transducer. At each point in time at least three measurements were performed and the mean of these recordings was taken as the subject's reading. Each measurement lasted about 5 s (5 heart beats).

Brachial artery pressure waveforms

Using applanation tonometry, pressure waveforms of the left brachial artery were recorded simultaneously with vessel wall movements. The applanation tonometer (Micro-tip® transducer, Millar Instruments Inc., Texas) is a pencil-like probe incorporating a small pressure sensitive transducer which is placed in contact with the skin at the site of the artery of interest and permits continuous and accurate recording of the local pressure waveform [14].

Blood pressure and heart rate

Both before and after vessel wall movement/pressure wave recordings, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), systolic blood pressure (SBP) and heart rate were each measured three times with a 1 min interval. These measurements were performed at the right upper arm using an oscillometric device (Dinamap®, Critikon Inc., Florida). At each point in time the mean of these recordings was taken as the subject's reading.

Forearm blood flow

Using ECG-triggered venous occlusion plethysmography forearm blood flow (FBF) of the left forearm was measured with mercury-in-Silastic strain gauges (Periflow, Janssen Scientific Instruments, Belgium) [15]. Both before and after occlusion of the hand circulation, by inflation of a wrist cuff to 240 mmHg, FBF was recorded for 2 min. Because of instability of blood flow after wrist occlusion, hand circulation was occluded at least 1 min before FBF measurements were repeated. FBF was recorded for 3 heart beats every 5 beats by intermittent inflation of an upper arm cuff to a pressure of 45 mmHg. FBF measurements obtained without occlusion of the hand circulation refer to total FBF (FBFtotal). FBF recordings obtained during occlusion of the hand circulation refer predominantly to the forearm skeletal muscle perfusion (FBFmuscle).

Pharmacokinetic assessments

Just before drug administration (0 h), at 10, 20, 30 and 45 min and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 24 and 32 h after drug administration, venous blood samples (8 ml) were collected in heparinized tubes from an antecubital vein of the left forearm. Within 2 h after collection, plasma was separated by centrifugation (10 min at 1500 g), frozen at −20 ° C and stored at −80 ° C until analysis.

Analytical methods

DHE plasma concentrations were measured in duplicate using a specific radioimmunoassay (r.i.a.) as previously described [16]. The lower limit of quantification was determined to be 50 pg ml−1. The slopes of the standard curves were consistent with correlation coefficients > 0.995. The variability of the calibration standards was less than 5%.

Data analysis

Pharmacodynamic data

First, the pressure waveforms recorded with applanation tonometry were calibrated. By definition, brachial artery pulse pressure (ΔP) as measured with applanation tonometry equals the pulse pressure (= SBP-DBP) as measured with the oscillometric device. Thus the nadir and peak of the pressure waveforms as recorded with applanation tonometry were equalled to DBP and SBP, respectively. Subsequently, by integrating the area under the pressure-time curve of the brachial artery and dividing it by the duration of the cardiac cycle, mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated.

After pressure wave calibration, diameter-time recordings (ultrasound) and pressure-time recordings (applanation tonometry) were analysed simultaneously using commercially available software (Matlab®) and an analytical program developed by the biophysics department of the university [17]. By constructing pressure-diameter curves, vessel wall properties were calculated over the operating pulse pressure according to the following equations: distensibility coefficient, DC = (ΔA/A)/ΔP, and cross-sectional compliance, CC = ΔA/ΔP, where A is the end diastolic cross sectional area (A = π(D/2)2) and ΔA the change in cross sectional area during the cardiac cycle (ΔA = π(((D + ΔD)/2)2−(D/2)2). To assure that changes in vessel wall properties resulted directly from drug-induced changes rather than indirectly from changes in blood pressure, isobaric vessel wall properties were also calculated within a predefined pressure interval of 85–95 mmHg (isobaric distensibility, DCiso and isobaric compliance, CCiso).

Total (FVRtotal) and muscular forearm vascular resistance (FVRmuscle) were calculated as MAP divided by FBFtotal and FBFmuscle, respectively, and expressed as arbitrary units (AU).

Pharmacokinetic data

According to Schran et al. [18], after subcutaneous administration, at each point in time (t) DHE plasma concentration C(t) can be described by a tri-exponential function: C(t) = A.e−α.t + B.e−β.t – (A + B).  where A and B are coefficients referring to fictitious plasma concentrations of DHE at time zero and ka, α and β are rate constants referring to the absorption of DHE and the rapid and slow phase of decline in plasma concentration, respectively. The equation was fitted to the experimental data to obtain the relevant pharmacokinetic constants of each subject. The pharmacokinetic software program MW/PHARM (Medi/Ware, Centre of Pharmacy, University of Groningen, The Netherlands) was used for the model fitting. Peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to reach Cmax (tmax) were determined from the plasma concentration-time curve of each subject. Half-lives of absorption (t½,abs), distribution (t½,λ1) and elimination (t½,λz) were calculated as 0.693/ka, 0.693/λ1 and 0.693/λz, respectively. The total area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) was calculated by the linear trapezoidal method and extrapolation to infinity. Assuming complete absorption from the injection site, plasma clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (V) of DHE were calculated as dose/AUC and CL/λz, respectively.

where A and B are coefficients referring to fictitious plasma concentrations of DHE at time zero and ka, α and β are rate constants referring to the absorption of DHE and the rapid and slow phase of decline in plasma concentration, respectively. The equation was fitted to the experimental data to obtain the relevant pharmacokinetic constants of each subject. The pharmacokinetic software program MW/PHARM (Medi/Ware, Centre of Pharmacy, University of Groningen, The Netherlands) was used for the model fitting. Peak plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to reach Cmax (tmax) were determined from the plasma concentration-time curve of each subject. Half-lives of absorption (t½,abs), distribution (t½,λ1) and elimination (t½,λz) were calculated as 0.693/ka, 0.693/λ1 and 0.693/λz, respectively. The total area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) was calculated by the linear trapezoidal method and extrapolation to infinity. Assuming complete absorption from the injection site, plasma clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (V) of DHE were calculated as dose/AUC and CL/λz, respectively.

Statistical analysis

All pharmacodynamic data were plotted as a function of time and the area under the parameter time-curves after placebo and after DHE compared using a paired Student's t-test. The differences in AUC after placebo and DHE are presented as 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). In case of a significant difference (P < 0.05), post hoc paired Student's t-tests were performed to determine the time course of the difference. Data are presented as mean ±s.e. mean.

Results

Six subjects reported that the subcutaneous injection of DHE was painful (mild to moderate). Two subject reported minor gastro-intestinal side-effects (nausea, watery stools and flatulence) which were probably drug related and resolved spontaneously. After placebo no adverse events were reported.

Pharmacokinetics

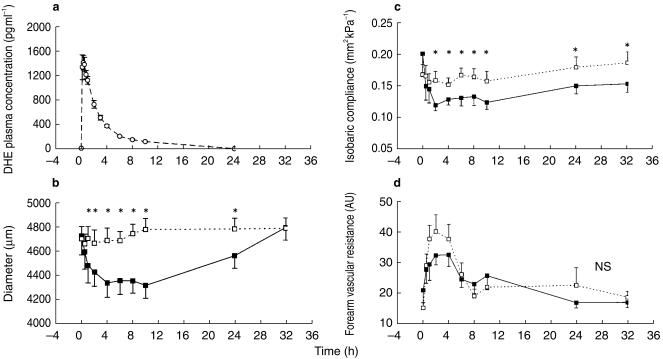

DHE (0.5 mg) was rapidly absorbed (t½,abs 0.11 ± 0.03 h) and reached a maximum plasma concentration of 1419 ± 88 pg ml−1 (Cmax) at 20 min (tmax=0.33 ± 0.08 h) after subcutaneous injection (Figure 1a). The half-lives of distribution (t½,λ1) and elimination (t½,λz) averaged 0.92 ± 0.16 and 5.63 ± 1.15 h, respectively. Mean CL, V and AUC were 95 ± 9 l h−1, 739 ± 114 l and 5825 ± 667 pg ml−1 h, respectively.

Figure 1.

a) The plasma-concentration-time curve of dihydroergotamine (DHE) after a single subcutaneous administration of 0.5 mg (○, dashed line). Time course of brachial artery diameter (b) and isobaric compliance (c) after placebo (□, dashed line) and DHE (▪, solid line). d) Time course of total forearm vascular resistance after placebo (□, dashed line) and DHE (▪, solid line). Data are presented as mean±s.e. mean (n = 10). *Time points with P < 0.05 for difference between DHE and placebo; NS: no statistically significant difference.

Pharmacodynamics

Haemodynamic parameters

Pre-drug SBP (112 ± 3 mmHg), DBP (59 ± 2 mmHg), MAP (80 ± 2 mmHg), pulse pressure (52 ± 2 mmHg) and heart rate (58 ± 2 beats min−1) before placebo were comparable with those before DHE. The area under the parameter-time curves after placebo and DHE did not differ (Table 1). The time course of the haemodynamic parameters was similar after placebo and DHE.

Table 1.

Pharmacodynamic data (n = 10)

| ΔAUC (95% CI) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|

| Haemodynamic parameters | ||

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg h) | 90 (−11/191) | 0.07 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg h) | 47 (−40/133) | 0.26 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg h) | 17 (−63/96) | 0.65 |

| Pulse pressure (mmHg h) | 43 (−23/110) | 0.18 |

| Heart rate (beats min−1 h) | 31 (−71/134) | 0.51 |

| Brachial artery wall properties | ||

| Diameter (mm h) | −8.812 (−12.97/−4.650) | 0.001 |

| Distension (µm h) | −790 (−1359/−222) | 0.012 |

| DCiso (10−3 kPa−1 h) | −17.5 (−47.7/12.6) | 0.22 |

| CCiso (mm2 kPa−1 h) | −0.98 (−1.61/−0.34) | 0.007 |

| Forearm vascular resistance | ||

| FVRtotal (AU h) | −62 (−246/121) | 0.46 |

| FVRmuscle (AU h) | 52 (−94/199) | 0.44 |

Pharmacodynamic data after the subcutaneous administration of 0.5 mg DHE. Data are presented as mean difference between the area under the parameter-time curve after placebo and after DHE (ΔAUC). 95% CI: 95% confidence interval. DCiso (isobaric distensibility coefficient) and CCiso (isobaric compliance coefficient) calculated over a predefined pressure interval of 85–95 mmHg. FVRtotal and FVRmuscle: total and muscular forearm vascular resistance, respectively.

P value of treatment differences by paired Student's t-test.

Brachial artery wall properties

Pre-drug diameter (4.698 ± 0.096 mm), distension (179 ± 14 µm), DCiso (9.39 ± 1.01 10−3 kPa−1) and CCiso (0.167 ± 0.016 mm2 kPa−1) before the administration of placebo and DHE did not differ. After DHE, the AUC for diameter, distension and cross-sectional compliance decreased (Table 1). Compared with placebo, diameter decreased (P < 0.05) from 1 until 24 h after DHE (Figure 1b); a maximum difference of 462 ± 60 µm (9.7%, P < 0.001) was measured 10 h after drug administration. Distension decreased from 2 until 8 h after DHE whereas CCiso decreased from 2 until 32 h (Figure 1c). Compared with placebo, a maximum difference in distension (34 ± 7 µm or 17.5%, P = 0.002) and CCiso (3.91 ± 1.34 10−2 mm2 kPa−1 or 24.8%, P = 0.017) was observed 6 and 2 h after drug administration, respectively.

Forearm vascular resistance

Pre-drug FVRtotal (15.0 ± 1.8 AU) and FVRmuscle (30.4 ± 3.1 AU) were similar in both study periods. The area under the parameter-time curves after placebo and DHE did not differ statistically (Table 1). The time course of the forearm vascular resistance was comparable after placebo and DHE (Figure 1d).

Discussion

The vascular effects of ergot alkaloids depend on the dose and route of administration, the species and tissue under investigation and the pre-existing vascular tone [3]. In the present study both the arterial and arteriolar effects of DHE were investigated at the level of the forearm. Therefore, DHE 0.5 mg, which is regarded a clinically relevant dose and is used in the acute treatment of migraine [19], was administered subcutaneously. Following this administration, both brachial artery diameter and cross sectional compliance, slowly decreased and remained decreased for at least 24 h. These data do not support the contention of DHE being a selective venoconstrictor and argue against DHE lacking peripheral arterial effects as reported by Andersen et al. [12]. However, their data should be interpreted with caution. Andersen and coworkers assessed arterial effects indirectly by measuring changes in toe-arm systolic blood pressure gradients whereas the present data refer to direct measurements at the brachial artery. Consequently, regional differences between the upper and lower extremities in vascular reactivity to DHE might have contributed to these conflicting results. In addition, in contrast with the present study, the previous study was not placebo-controlled and did not feature a double-blind design.

In contrast with the effects of DHE on conduit arteries neither total nor muscular forearm vascular resistance were affected by DHE and blood pressure did not change. These data indicate the absence of both local and systemic drug-induced vasoconstriction of resistance arteries and are in agreement with previous research demonstrating that DHE does not affect skeletal muscle perfusion [20]. Although blood pressure is often reported to rise in response to DHE [3], the absence of a systemic vasopressor effect under experimental conditions similar to those of the present study is not exceptional [8, 21] and is likely due to the low dose of DHE administered. Taken together our data demonstrate that at the dose used, DHE induces a potent and long-lasting arterial vasoconstriction and decreases compliance without affecting resistance arteries of the forearm.

The pharmacokinetic parameters observed in the present study are comparable with those previously reported after parenteral administration of DHE [18, 22]. After subcutaneous administration DHE was quickly taken up into the systemic circulation and reached peak plasma concentrations within 30 min. Following absorption, DHE plasma levels rapidly declined in a biphasic fashion, suggesting fast tissue distribution into a peripheral compartment before being eliminated. Although the terminal half-life observed in the present study is in agreement with several previous reports [18, 22, 23], others disagree and report a much slower elimination [21]. Different results are probably related to different analytical assays used to determine DHE plasma concentrations and to different dosages of DHE used. Because of the relative low dose of DHE administered in the present study and despite the use of a validated r.i.a., from 24 h after drug administration plasma levels were below the detection limit. Consequently, it cannot be excluded that terminal half-life was underestimated.

In accordance with its potent and long lasting venoconstrictor activity reported by Aellig et al. [6, 8], the arterial effects of DHE observed in the present study are also characterized by a slow onset and long duration of action which correlates poorly with plasma levels. How can the discrepancy between the pharmacokinetics of DHE and its prolonged vascular activity be explained? The long-terminal half-life of DHE and its extensive metabolism which results in the formation of active metabolites [21, 24] provide possible explanations for the prolonged vascular activity of DHE in vivo. However, these arguments cannot explain the sustained vasoconstrictor activity of ergot alkaloids in vitro which persists even after repeated washing [9, 10]. Therefore, as is suggested by the large volume of distribution, tight tissue binding resulting in slow diffusion from the receptor biophase is likely to contribute substantially to these effects. As ergotamine displays a comparable discrepancy between pharmacokinetics and long lasting arterial vasoconstriction [11] as well as an increase in arterial stiffness [25], these properties seem to be a common characteristic of the ergot alkaloids as a class.

How do these vascular effects translate into the therapeutic use of DHE? In orthostatic hypotension the beneficial effects of DHE are believed to result from the constriction of venous capacitance vessels thereby promoting venous return and subsequently cardiac output [3]. In migraine however, many mechanisms have been proposed, including constriction of large cranial extracerebral arteries and closure of arteriovenous anastomoses [2]. It is tempting to speculate that at the cranial arteries ergot alkaloids display the same long lasting vascular effects as at peripheral arteries. If so, this might explain why headache recurrence after the initially successful treatment of acute migraine is far less frequent after the use of DHE compared with the use of short acting selective 5-HT1B/1D-receptor agonists [26].

In summary, DHE decreases brachial artery diameter and compliance while forearm vascular resistance remains unchanged. Consequently, DHE acts on conduit arteries without affecting resistance arteries. Furthermore, a discrepancy was demonstrated between the plasma concentrations of DHE which rapidly reach peak levels and quickly decline, and its long lasting vasoconstrictor activity.

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to G. Kalafsky and D. Katzgrau (Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, East Hannover, New Jersey, U.S.A.) for performing dihydroergotamine plasma concentration assessments.

References

- 1.Silberstein SD, Young WB. Safety and efficacy of ergotamine tartrate and dihydroergotamine in the treatment of migraine and status migrainosus. Neurology. 1995;45:577–584. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silberstein SD. The pharmacology of ergotamine and dihydroergotamine. Headache. 1997;37:S15–S25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark BJ, Chu D, Aellig WH. Actions on the heart and circulation. In: Berde B, Schild HO, editors. Ergot alkaloids and related compounds. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer-Verlag; 1978. pp. 321–420. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller-Schweinitzer E. What is known about the action of dihydroergotamine on the vasculature in man? Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1984;22:677–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller-Schweinitzer E, Rosenthaler J. Ex vivo studies after oral treatment of the beagle with dihydroergotamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1983;89:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90601-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aellig WH. A new technique for recording compliance of human hand veins. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;11:237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1981.tb00527.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Marees H, Welzel D, de Marees A, Klotz U, Tiedjen KU, Knaup G. Relationship between the venoconstrictor activity of dihydroergotamine and its pharmacokinetics during acute and chronic oral dosing. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;30:685–689. doi: 10.1007/BF00608216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aellig WH, Rosenthaler J. Venoconstrictor effects of dihydroergotamine after intranasal and intramuscular administration. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1986;30:581–584. doi: 10.1007/BF00542418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostergaard JR, Mikkelsen E, Voldby B. Effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine and ergotamine on human superficial temporal artery. Cephalalgia. 1981;1:223–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1981.0104223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maassen van den Brink A, Reekers M, Bax WA, Ferrari MD, Saxena PR. Coronary side-effect potential of current and prospective antimigraine drugs. Circulation. 1998;98:25–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tfelt-Hansen P, Paalzow L. Intramuscular ergotamine: plasma levels and dynamic activity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1985;37:29–35. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen AR, Tfelt-Hansen P, Lassen NA. The effect of ergotamine and dihydroergotamine on cerebral blood flow in man. Stroke. 1987;18:120–123. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.1.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoeks APG, Brands PJ, Smeets FAM, Reneman RS. Assessment of the distensibility of superficial arteries. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1990;16:121–128. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(90)90139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly R, Hayward C, Ganis J, Daley J, Avolio A, O'Rourke M. Noninvasive registration of the arterial pressure pulse waveform using high-fidelity applanation tonometry. J Vasc Med Biol. 1989;1:142–149. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benjamin N, Calver A, Collier J, Robinson B, Vallance P, Webb D. Measuring forearm blood flow and interpreting the responses to drugs and mediators. Hypertension. 1995;25:918–923. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.5.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenthaler J, Munzer H, Voges R, Andres H, Gull P, Bolliger G. Immunoassay of ergotamine and dihydroergotamine using a common 3H-labelled ligand as tracer for specific antibody and means to overcome experienced pitfalls. Int J Nucl Med Biol. 1984;11:85–89. doi: 10.1016/0047-0740(84)90040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Hoon JNJM, Hoeks APG, Willigers JM, Van Bortel LMAB. Non-invasive assessment of pulse pressure at different peripheral arteries in man. Neth J Med. 1998;52:A36. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schran HF, Tse FLS. Pharmacokinetics of dihydroergotamine following subcutaneous administration in humans. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1985;23:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: appropriate use of ergotamine tartrate and dihydroergotamine in the treatment of migraine and status migrainosus. Summary statement. Neurology. 1995;45:585–587. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.3.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mellander S, Nordenfelt I. Comparative effects of dihydroergotamine and noradrenaline on resistance, exchange and capacitance functions in the peripheral circulation. Clin Sci. 1970;39:183–201. doi: 10.1042/cs0390183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wyss PA, Rosenthaler J, Nuesch E, Aellig WH. Pharmacokinetic investigation of oral and iv dihydroergotamine in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;41:597–602. doi: 10.1007/BF00314992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humbert H, Cabiac M-D, Dubray C, Lavene D. Human pharmacokinetics of dihydroergotamine by nasal spray. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;60:265–275. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schran HF, Tse FLS, Chang C-T, Hunt TL, Saxe MA, Ventura DF, et al. Bioequivalence and safety of subcutaneously and intramuscularly administered dihydroergotamine in healthy volunteers. Cur Ther Res. 1994;55:1501–1508. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller-Schweinitzer E. Pharmacological actions of the main metabolites of dihydroergotamine. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1984;26:699–705. doi: 10.1007/BF00541928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barenbrock M, Spieker C, Witta J, Evers S, Hoeks APG, Rahn KH, et al. Reduced distensibility of the common carotid artery in patients treated with ergotamine. Hypertension. 1996;28:115–119. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Hoon JNJM, Willigers JM, Troost J, Struijker-Boudier HAJ, Van Bortel LMAB. Vascular effects of 5-HT1B/1D-receptor agonists in patients with migraine headaches. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:418–426. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.110502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]