Abstract

Purpose:

This study sought to address 2 questions: (1) Can groups of family management trajectories be identified in early adolescence? (2) How are the different family management trajectories related to trajectories of violent offending for youths ages 13-18?

Methods:

Analyses used semi-parametric group-based modeling (SGM) to identify groups of family management trajectories. A joint trajectory method was used to predict patterns of youth violence conditional on family management.

Results:

Analyses identified 3 trajectories of family management from age 11-14: (1) stable low, (2) stable high, and (3) increasing family management. Youths from families in the low family management trajectory were more likely than others to follow chronic and late onset trajectories of violence. In contrast, youths in stable-high positive family management were less likely to engage in violence from age 13 to age 18. Further, youths whose families started low, but increased to high family management, had patterns of adolescent violence similar to those whose parents were consistently high in their use of good parenting practices.

Conclusions:

The current study advances knowledge of developmental patterns in family management and youth violence. Although most parents remained stable in family management practices from age 11 to 14 (stable high or stable low), parents who started low, but improved their management practices during middle school, had children with lower levels of chronic and late onset violence than those who remained low. Findings suggest that interventions developed to enhance family management practices may reduce risk for violence in later adolescence.

Keywords: youth violence trajectories, risk and protective factors, family management

Introduction

Family management practices can affect youths' risk for becoming involved in antisocial behavior, including delinquency and violence [1-5]. Family management, broadly defined, includes level of supervision, methods of discipline, the degree to which parents or adult caretakers communicate clear expectations for their children's behavior, and the degree of praise and reinforcement forthcoming from parents for positive behavior [3].

Using data from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development, Farrington [6] found that poor supervision and punitive discipline of children as early as age 8 increased the risk of later, self-reported violence and violent crime convictions into adulthood among the boys in the study. In addition, the study showed that an authoritarian parenting style and cruel, passive, or neglecting parental attitudes heightened a child's risk for later violence. Wells and Rankin [7] also found that the risk of violence among adolescents increased with either highly strict or highly permissive parenting styles. In the Pittsburgh Youth Study, Farrington, Loeber, Yin, & Anderson [8] found that poor parental supervision and low parental reinforcement (e.g., praise) were correlated with the frequency of delinquent acts in males.

The link between family management practices and youth violence also has been explored in the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP). Herrenkohl and colleagues [4] found that poor family management in middle school (age 14)--measured by supervision, rules, and praise-- significantly increased the risk of self-reported violence in youths at age 18 (OR=2.11). At age 16, poor family management was even more strongly predictive of youth violence (OR=2.63). However, poor family management measured at age 10 did not predict violence among adolescents in the study. Thus, family management practices appeared more strongly linked to violent behavior when measured proximally to the outcome, thereby raising the possibility of differences in parenting and risk of violence as a function of children's age and stage of development.

The above findings are important, yet limited by the measurement of both family management practices and violent behavior at fixed time points. Examination of the degree to which changes in family management during adolescence result in changes in the likelihood of violent behavior requires use of multiple data points and methods suited to analyzing both linear and nonlinear patterns of behavior, namely latent growth curve modeling or growth mixture modeling. Latent growth modeling (LGM) examines trajectories of a behavior over time; growth mixture modeling further allows for the identification of distinct trajectory groups within a given population [9-15].

Dishion et al. [16] recently used LGM and hierarchical multiple regression analyses to assess the degree to which changes in family management practices for males (from age 9-10 to age 15-16) were associated with use of drugs and involvement in antisocial behavior. Descriptive analyses showed that parents of antisocial boys (boys who started antisocial behavior early and then persisted through adolescence) were more likely than were parents of well-adjusted boys to decrease their use of good family management practices in early adolescence. While family management had no unique main effect on antisocial behavior in late adolescence, after controlling for earlier antisocial behavior (age 9-10), it did interact with deviant peer processes in predicting a higher level of antisocial behavior in the sample as a whole.

Additionally, several studies have used LGM and mixture modeling to examine childhood aggression and youth violence. For example, Nagin and Tremblay [12] used a growth mixture modeling approach to study patterns of aggression in a prospective longitudinal study of boys (ages 6-15) in Montreal. They found 4 trajectory groups: (1) a group comprised of boys with consistent low-level physically aggressive behavior, (2) one comprised of boys who showed signs of having desisted from physical aggression by age 12, (3) one with boys who began as highly aggressive at age 6 and then declined to low levels of aggression by adolescence, and (4) one with boys who began as aggressive and subsequently maintained a persistent pattern of physical aggression over measured time points.

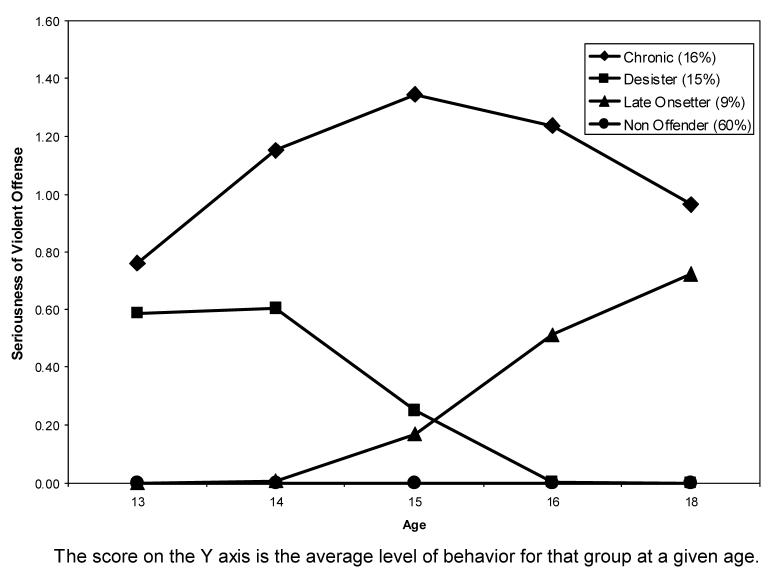

In the Seattle Social Development Project, Hill et al. [17] used growth mixture modeling to identify 4 adolescent (age 13-18) violence trajectory groups: nonoffenders, late onsetters, desisters, and chronic offenders. The nonoffender group appeared not to have engaged in violence during the study period. The late onsetter group displayed no violence until age 14 but gradually increased to low levels of violence by age 18. The desister group displayed low levels of violence initially, but, by age 16, had largely desisted from violence. Finally, the chronic offender group appeared to have perpetrated violence over the full course of adolescence.

In that same study, Hill and colleagues examined predictors of trajectory group membership at 2 fixed time points, childhood (age 10-11) and mid-adolescence (age 15). Family management practices measured at age 10-11 distinguished late onset offenders from nonoffenders, but failed to distinguish among youths in several other trajectory comparisons (e.g., early onsetters versus nonoffenders and chronic offenders versus desisters).

The above research helps to advance knowledge of the developmental patterns that characterize youth violence and family management. However, no study has yet jointly examined how developmental changes in family management interact with changes in youth violence perpetration. A study of joint trajectories could reveal whether an increase or decline in use of family management strategies is associated with concomitant patterns of desistence, maintenance, or escalation of violence among adolescents. Dynamic examination of family management practices and violence during adolescence is particularly important given the rise in the incidence and prevalence of violence during this age period [4, 16, 18-20].

In the current study, we seek to learn about the degree to which change and stability in family management practices predict previously established patterns of youth violence [17], measured over a 7-year period, from age 11 to age 18 of participating adolescents. Multiple waves of data from a prospective longitudinal study are used in analyses. Positive family management is operationalized here as parents or adult caretakers setting clear rules and expectations for behavior within and outside the family, providing consistent supervision, and reinforcing and encouraging good behavior and productive work habits in their children [3, 4].

Dishion and colleagues [16] provide evidence of stable high and declining patterns of management in relation to antisocial behavior of adolescents. Thus, we hypothesized we would find similar patterns in our data. Specifically, we expected to find families in which consistently good family management was practiced across the study period, as well as families in which family management was on a decline. Additionally, we hypothesized some parents would begin and remain consistently poor in their use positive management over time. And, finally, we hypothesized that perhaps a small percentage of parents would actually become more conscientious managers of their children's social interactions during adolescence. Here, we reasoned that some caregivers will naturally do better as parents of adolescents, with whom there may be more opportunity for joint problem-solving and negotiation of outcomes [21].

As for the relation between family management and youth violence, we hypothesized that a decreasing use of positive management practices would lead to an increasing use of violence on the part of adolescents, whereas a stable high or increasing use of positive management would help to prevent and/or reduce ongoing violence. We reasoned that positive family management would curtail social interactions that reinforce antisocial behavior (e.g., involvement with antisocial peers) while strengthening parent-child bonds. Indeed, evidence suggests that negative peer involvement can increase the likelihood of various forms of antisocial behavior in adolescents [3], whereas strong parent-child bonds appear to lessen antisocial behavior by increasing a child's stake in conforming to the rules of his/her family [16, 22].

Method

Participants

Data are from the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP), a longitudinal, theory-driven study. In September of 1985, participants were recruited from 18 elementary schools serving high-crime neighborhoods of Seattle. Of the 1,053 eligible students, 808 (77%) agreed to take part in the longitudinal study. Of the original study participants, 396 (49%) were female, 386 (47.8%) were European-American, 203 (25.1%) were African-American, 174 (21.5%) were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 45 (5.6%) were Native American or Alaska Native. Many participants were from low-income households. Forty-six percent of parents reported yearly incomes under $20,000 in 1985. Fifty-two percent of children participated in the school free lunch program at some point between the fifth and seventh grades. Forty-two percent of children reported living with a single parent in 1985. Further discussion of the SSDP sample and methods of recruitment can be found in earlier papers [19, 23, 24].

Assessments

In the fall of 1985, data were collected when most students were 10 years of age (median age was 10.7 years, M = 10.8, SD = .52). Thereafter, data were collected in the spring of each year through 1991, when participants were about 16 years of age. Data were collected again in the spring of 1993, at age 18. Initially, participants completed group-administered questionnaires in their classrooms. Beginning in 1988, participants were interviewed in person and asked for their confidential responses to a wide range of questions regarding family, peers, school, and community, as well as their attitudes and experiences with substance use, delinquency, and violence. The interviews took about one hour. Early in the study, youths received a small incentive (e.g., an audiocassette tape) for their participation and later they received monetary compensation. Signed parental consent was obtained from youths prior to age 18 (assent also was obtained from youths); after age 18 youths directly consented to take part in the study. Data collection procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the University of Washington.

Data from 7 waves of the SSDP panel are used in the current study, corresponding to assessments carried out when participants were 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 18 years of age. Participation rates across all study waves in the SSDP are consistently high. At age 11, 703 (87%) of the original youth sample of 808 was reassessed; from age 14 to age 18 over 94% of the original sample was assessed.

Measures

Family management from age 11-14

Measures of parents' family management practices were developed from youths' reports at age 11-14. At each age, youths responded to 6 items. They were asked: “When you are away from home, do your parents know where you are and who you are with?”; “When you misbehave, do your parents take time to calmly discuss what you have done wrong?” They also responded to the following statements: “The rules in my family are clear”; “My parents praise me for my school achievements”; “My parents notice when I am doing a good job and let me know about it”; “My parents put me down” (reversed). Responses were scored on a 4-point scale (NO!, no, yes, YES!); scores were standardized and combined at each age. Standardized scale reliabilities range from .66 at age 11 to .71 at age 12. Composite scales at each age were dichotomized using a median split to characterize high and low levels of good family management.

Violent offending from age 13-18

A violent offense seriousness scale was developed for youths at each age, 13-18 [17]. Seriousness measures allow researchers to distinguish among violent offenders who have engaged in a moderate number of violent offenses by taking into account the gravity of each violent offense [25]. Youths were given a score at each age for the most serious act of violence they reported: picked a fight, committed assault, and committed robbery. For “picked a fight” and “assault” 3 or more acts each were required before a youth was considered having engaged in violence on the indicator. These thresholds were used to avoid including infrequent violent encounters, possibly resulting from situational factors, as indicators of violent offending.

Data were arranged according to levels of violence seriousness [26]: Level 0 denotes “nonoffending”; level 1 denotes involvement in minor violence (fighting); level 2 denotes involvement in moderate violence (assault); and level 3 denotes involvement in serious violence (robbery).

Previous analyses of these data [17] identified 4 violent offending trajectory groups based on the above scoring method: nonoffenders, late onsetters, desisters, and chronic offenders (Figure 1). Figure 1 shows the observed trajectories for the 4-group model. In the SSDP, nonoffenders represent about 60% (n=479) of the sample, late onsetters about 8.8% (n=70) of the sample, desisters about 14.8% (n=118) of the sample, and chronic offenders about 16.3% (n= 130) of the sample.

Figure 1.

Youth Violence Trajectories

Analysis

The current study focused on the relation between trajectories of family management from age 11-14 and violence trajectory groups from ages 13 through 18. First, we sought to identify groups of trajectories of family management from age 11 to age 14 using growth mixture modeling. Then, we used a joint trajectory method to predict the likelihood of membership in each violence trajectory from each trajectory of family management [14, 27]. Analyses were conducted using a type of growth mixture modeling called semi-parametric group-based modeling (SGM) [9, 11-13, 15]. SGM is especially suited to analyzing longitudinal data in which information is sought on patterns of behavior for diverse groups within a population. The method offers an improvement over conventional correlation-based procedures, which are limited to measurements at only two time points and are sensitive to outlier data in highly skewed distributions [27].

SGM fits semi-parametric (discrete) mixtures of censored normal, Poisson, zero-inflated Poisson, and Bernoulli distributions, which often more closely reflect the distributions of antisocial behaviors. In addition, the SGM takes advantage of the time-ordered nature of responses, and is specifically designed to examine longitudinal data. Finally, the modeling approach includes all participants who have at least 2 data points to determine parameter estimates and their standard errors. Thus, SGM makes full use of available data in determining parameter estimates, and does not lose information through listwise deletion [15]. The SGM approach is available through a customized SAS macro [13-15], which was used for analyses presented here.

Model selection in SGM requires determination of the number of groups that best describe the data, which is complex because a K-group model is not nested within a K+1 group in the SGM. The Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) provides the basis for selecting the optimal model, since the BIC can be used for comparison of both nested and unnested models [28]. The model with the smallest absolute value BIC is generally chosen, but the BIC will tend to favor models with fewer groups because it rewards parsimony. Individuals are then assigned to the group that best conforms to their observed behavior according to the maximum posterior probability of group membership.1

The association between family management and violent offending trajectories was examined using conditional (transition) probabilities, also available in a SAS-based procedure. This approach is illustrated in Nagin and Tremblay's [14] analyses of data on boys in neighborhoods of Montreal. In that study, a joint trajectory approach was used to estimate the relationship between oppositionality in children (age 6-15) and later property offending (age 11-17). Transition probabilities were in this case used to show that a majority of boys who followed a pattern of low opposition subsequently followed a trajectory of low-property delinquency (53%); in contrast, a much smaller percentage of boys with chronic oppositionaility (20%) followed such a trajectory. A relatively large percentage of oppositional children were found to have followed a rising-chronic or medium-chronic delinquency trajectory. Brame and colleagues [27] also used a joint trajectory approach in their study of physical aggression in childhood as a precursor to aggression in adolescence.

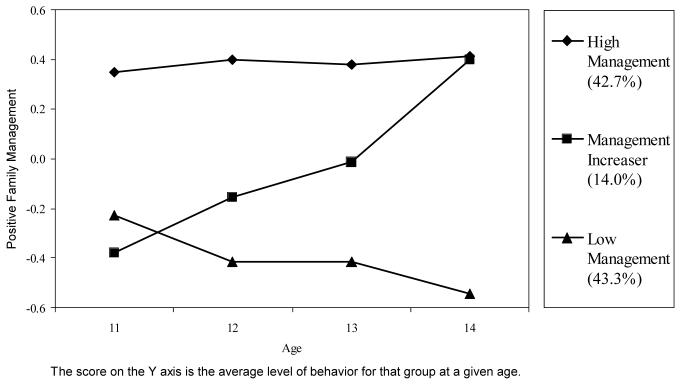

Results

First, we sought to identify groups of trajectories of family management from age 11 to age 14 using growth mixture modeling. We tested 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-group models. The 3-group solution proved to be the most efficient balance between parsimony and goodness of fit; that is, the BIC was minimized for the 3-group model. Figure 2 shows the trajectories consistent with this 3-group solution: (1) a pattern of stable high family management, (2) a pattern of low family management, and (3) a pattern of increasing use of positive family management. Accompanying probabilities of group membership are shown on the right hand side of Figure 2. Note that we did not find evidence of a declining pattern of family management, as originally hypothesized. However, there does appear to be some additional decline in positive management practices on the part of those parents who already were low on the family management scale at the start of adolescence (age 11). It is estimated that most parents of youth in the SSDP sample, by the time their children reached adolescence, were either stable high (42.7%, n=338) or low (43.3%, n=343) in their use of good family management practices, whereas about 14% (n=111) of parents appeared to increase their use of good family management through age 14.

Figure 2.

Family management trajectories from age 11-14.

Table 1 provides the mean posterior probabilities conditional on class assignment for the 3 trajectory groups, illustrating the accuracy of group classification. The average probabilities for the assigned groups are .93, .88, and .98 for low, increasing, and high family management respectively, indicating very low classification error in each case.

Table 1.

Mean posterior probabilities conditional on class assignment for the three trajectory groups

| Probability Conditional on Group Membership | Low | Increaser | High |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low family management | .93 | .03 | .00 |

| Management increaser | .06 | .88 | .02 |

| High family management | .01 | .09 | .98 |

| Total | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

We next used a joint trajectory method [14, 27] to predict the likelihood of membership in each violence trajectory from each of the three trajectories of family management. Table 2 shows transition probabilities for the family management and violent offender trajectories. These reflect the overlap in group membership for individuals assigned to each trajectory group and are based on the proportion of youths within each family management trajectory estimated to follow one of the four violence trajectories.2

Table 2.

Transition probabilities for violent offender and family management trajectory groups

| Transition Probability for Each Group |

Non- offenders |

Late Onsetters |

Desisters | Chronic Offenders |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Management | .53 | .13 | .18 | .16 |

| Management Increaser | .70 | .12 | .12 | .06 |

| High Management | .65 | .10 | .17 | .08 |

Results indicate that regardless of which pattern of family management was followed, the most likely outcome is non-offending. However, youths whose parents were consistently high in their use of good parenting practices (high management), and those whose parents increased their management over time (management increaser), were estimated to be highest among the nonoffenders (probabilities of .65 and .70, respectively). Additionally, youths of “high” managers and management increasers were estimated as least likely to become chronic offenders (probabilities of .08 and .06, respectively) and late onset offenders (probabilities of .10 and 12, respectively). In contrast, youths whose parents were consistently low in their use of good parenting practices (stable low management) were highest among the chronic and late onset offenders (probabilities of .15 and .13, respectively) and lowest among the nonoffenders (probability of .53). As shown in Table 2, the relation between family management and “desistence” from violence is less clear. In fact, youths of management increasers were estimated to be lower among desisters (probability of .12) than youths in the low management group (probability of .18).

Discussion

Evidence suggests that youths benefit when parents provide supervision, set clear rules and expectations for behavior, and reinforce good behavior in their children [22]. Collectively, these actions strengthen parent-child bonds, promote responsible behavior, and lessen opportunities for adolescents to become involved with antisocial peers [16, 29]. In this study, we sought to build on existing research by examining family management and youth violence as dynamic trajectories, seeking a more nuanced understanding of the developmental relationship between the 2 behaviors. Knowledge of this relationship could be used to guide approaches to youth violence prevention and juvenile justice interventions focused on strengthening families [30].

The current study used growth mixture modeling to study family management and youth violence as trajectories rather than static variables. Thus, analyses captured developmental changes in family management and violent behavior over a multiple–year span of time, and assessed how changes in family management practices relate to changes in violent behavior during a period of increasing use of violence [18].

Four trajectories of youth violence were examined alongside 3 trajectories of family management during adolescence (age 11-14): low, increasing, and high family management. By age 11, most (86.0%) of the families were either stable high (42.7%) or stable low (43.3%) in family management practices. Thus, these skills of parenting generally are consistent by the time children enter adolescence. However, 14% of the families appeared to improve their management practices during this transitional period without intervention. In fact, while this group registered lowest on the family management scale at age 11 for participating youths, a noted improvement in the score occurred by age 13, and, by age 14, the group score was comparable to that of the high management trajectory group. This is a particularly noteworthy finding, which suggests parenting practices are changeable even as families negotiate the demands of adolescence. In may be that this pattern characterizes what Dishion et al. [16] describe as tendency for some parents to become aware and take action to prevent the worsening of an emerging problem. It also may be that some parents naturally do better in their management of older children, with whom they can establish a more reciprocal, give-and-take relationship [21]. Further, the finding of a natural increaser group inspires hope that prevention efforts to improve family management during this developmental period may not be going against the stream but will instead build on a momentum to change, which, for some parents, is already underway.

A percentage of parents in our study appeared to begin and remain low in their use of positive family management, even showing some additional decline after age 13 for participating adolescents. Yet, the data did not produce a fourth group for whom positive family management practices markedly declined during the course of their children's adolescence, as originally hypothesized. This, too, is noteworthy in that our results do not support the notion of an overall worsening of family management as parents and children redefine the boundaries of their relationship in the context of children's growing independence. However, the fact that there was some further degradation in family management on the part of those caregivers who were low from the start may indicate a tendency for some parents to further disengage from children with whom relationship bonds have are already been strained by prior difficulties [16].

Examination of transition probabilities for the family management and violent offending joint trajectories in this study revealed that, as expected, a low level of family management during early adolescence was associated with a higher prevalence of chronic and late-onset violence. In contrast, a consistently high level of family management predicted a lower prevalence of violent offending, as did an increasing use of good family management. In fact, youths whose parents increased their use of positive management practices during adolescence were about as likely as those whose parents maintained a high level of family management from age 11 to follow a chronic violence trajectory (from ages 13-18), or to initiate violence after age 14. However, an increasing level of family management appeared less directly linked to a pattern of desistence in youth (who gradually lessened their use of violence). For these youth, other protective factors may be at play. For example, they may have become more resistant to negative peer influences. Or, they may simply have learned more productive ways of handling interpersonal conflict, as would be expected of youths who follow an adolescent-limited pattern of antisocial behavior [20].

There are some limitations to the current study. It focuses only on good family management, a single predictor among many that are known to be important in the etiology of youth violence [3-5]. Further research is needed to investigate the effects of changes in other known risk and protective factors as they relate to trajectories of violent behavior. Additionally, analyses are exploratory and do not control for demographic variables-- such as gender, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status-- that could affect the relation between family management and violence. Thus, further research is needed to investigate alternative hypotheses and to establish the relative importance and combined effects of family management alongside other predictors of violence within diverse community samples.

Overall, however, results of this study are encouraging for prevention programs that target parenting skills to lessen youth problems [16]. Combined with strategies of risk reduction and asset building within other contexts like schools and communities, parent training could very well have a beneficial impact on violence, while concurrently addressing a host of other co-existing problems, such as substance use and non-violent forms of delinquency [31]. This approach should benefit families in which parents' use of family management is on a decline, as well as those in which family management has been at a consistently low level.

Footnotes

Work on this article was supported by research grants # 1R24MH56587 and 1R24MH56599 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and # R01DA09679 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Posterior probabilities are estimates of the likelihood that an individual belongs to a trajectory group; using this probability an individual can be assigned to the group that best describes his/her behavior; the closer to 1, the more well matched an individual is to that group

Transition probabilities are computed in a joint estimation procedure, which provides estimates of the proportion of the population that follow each developmental pattern.

Reference List

- 1.Brewer DD, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, et al. Preventing serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offending: A review of evaluations of selected strategies in childhood, adolescence, and the community. In: Howell JC, Krisberg B, Hawkins JD, Wilson JJ, editors. A Sourcebook: Serious, Violent, and Chronic Juvenile Offenders. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. pp. 61–141. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capaldi DM, Patterson GR. Can violent offenders be distinguished from frequent offenders? Prediction from childhood to adolescence. J Res Crime Delinq. 1996;33:206–231. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins JD, Herrenkohl T, Farrington DP, et al. A review of predictors of youth violence. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 106–146. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herrenkohl TI, Maguin E, Hill KG, et al. Developmental risk factors for youth violence. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26:176–186. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipsey MW, Derzon JH. Predictors of violent or serious delinquency in adolescence and early adulthood: A synthesis of longitudinal research. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 86–105. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrington DP. Early predictors of adolescent aggression and adult violence. Violence Vict. 1989;4:79–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells LE, Rankin JH. Direct parental controls and delinquency. Criminol. 1988;26:263–285. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrington DP, Loeber R, Yin Y, et al. Are within-individual causes of delinquency the same as between-individual causes? Crim Behav Ment Health. 2002;12:53–68. doi: 10.1002/cbm.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Nagin DS. Offending trajectories in a New Zealand birth cohort. Criminol. 2000;38:525–551. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. MPlus User's Guide. Third ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagin DS, Land KC. Age, criminal careers, and population heterogeneity: specification and estimation of a nonparametric, mixed Poisson model. Criminol. 1993;31:327–362. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagin D, Tremblay RE. Trajectories of boys' physical aggression, opposition, and hyperactivity on the path to physically violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquency. Child Dev. 1999;70:1181–1196. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Analyzing developmental trajectories of distinct but related behaviors: A group-based method. Psychol Methods. 2001;6:18–34. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29:374–393. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM. Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behavior. J Adolesc. 2004;27:515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill KG, Herrenkohl TI, Chung I-J, et al. Developmental predictors of adolescent violence trajectories. under review. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliott DS. Serious violent offenders: Onset, developmental course, and termination. The American Society of Criminology 1993 Presidential Address. Criminol. 1994;32:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Kosterman R, et al. Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:226–234. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1998;1:61–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1021800432380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and Crime: Current Theories. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Battin SR, Hill KG, Abbott RD, et al. The contribution of gang membership to delinquency beyond delinquent friends. Criminol. 1998;36:93–115. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, et al. Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance use: A test of the social development model. J Drug Issues. 1996;26:429–455. doi: 10.1177/002204269602600207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung I-J, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, et al. Childhood predictors of offense trajectories. J Res Crime Delinq. 2002;39:60–90. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfgang ME, Figlio RM, Tracy PE, et al. The National Survey of Crime Severity (NCJ-96017) Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brame B, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE. Developmental trajectories of physical aggression from school entry to late adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42:503–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factor. J Am Stat Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patterson GR, Yoerger K. Intraindividual growth in covert antisocial behaviour: A necessary precursor to chronic juvenile and adult arrests? Crim Behav Ment Health. 1999;9:24–38. [Google Scholar]

- 30.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Youth Violence: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; Rockville, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wasserman GA, Miller LS. The prevention of serious and violent juvenile offending. In: Loeber R, Farrington DP, editors. Serious and Violent Juvenile Offenders: Risk Factors and Successful Interventions. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 197–247. [Google Scholar]