Abstract

Aims

To examine a) the use of lipid-lowering drugs in North Jutland County in Denmark from 1991 to 1998 and b) the pattern of usage according to sex and age.

Methods and results

We used the Pharmaco-Epidemiological Prescription Database in the county to identify all reimbursed prescriptions for lipid-lowering therapy from 1991 to 1998. One-year incidence rates (IR) and prevalence (P) of the use of lipid-lowering drugs were calculated. Both IR and P of patients in lipid-lowering therapy were stable until 1994, with the IR below 100 per 100 000 for both sexes. The IR then increased from 59.9 to 236.5 per 100 000 person-years in 1998 for women, and from 88.6 to 322.8 per 100 000 person-years for men. The utilization patterns were identical between the sexes. Thus, in both women and men the highest prevalence and incidence rates of lipid-lowering drug therapy were seen in the 60–69-year-olds. Furthermore, the marked increase in both prevalence and incidence of persons on lipid-lowering drug therapy between 1994 and 1998 was the result of an increased number of prescriptions in the 50–59, 60–69 and 70 + years olds, in both women and men. There was a remarkable 4–5 fold increase in the numbers of new patients who received statins during the same period.

Conclusions

The overall use of lipid-lowering drugs has increased markedly over the last few years in Northern Jutland, Denmark. The increase began following publication of the first major trial documenting the benefit of therapy with statins.

Keywords: epidemiology, lipid-lowering drugs, prescription

Introduction

There now exists an extensive body of scientific documentation, consisting of prospective epidemiological studies, clinical investigations, randomised trials and experimental animal models, demonstrating a causal association between serum cholesterol and risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) [1–6].

Several randomized trials, including the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) [7], CARE [8], WOSCOP [9], and others [10–12], have provided evidence for a positive effect of lipid-lowering treatment on mortality and morbidity in patients with CHD and/or hypercholesterolaemia. Thus, recent meta-analyses of clinical trials using 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors (statins) have demonstrated that treatment with these drugs reduces low density lipoprotein (LDL-C) and clearly decreases the risk of mortality from any causes, CHD and stroke with a relative risk reduction of 21–32% [13–15]. Furthermore, therapy with statins seems to be associated with a low rate of adverse effects [8, 12, 16].

An increase in the use of lipid-lowering drugs has subsequently been reported in various countries [17–21]. However, there appears to be large variations according to geography [19, 22], physician specialty [22], and patient characteristics, e.g. age, sex and comorbidity [16, 19, 20, 22], and socioeconomic factors [17]. These differences are also related to the persistence of use [21, 24]. There are only a few population-based drug-utilization studies of lipid-lowering drugs, although they constitute an ever increasing proportion of prescriptions and costs in Western health care systems [17–20, 24]. More up-dated information on time trends based on individual level data are needed.

From this background, we examined recent temporal patterns of lipid-lowering drug use, i.e. 1 year incidence rates (number of new users per 100 000 inhabitants) and prevalence (number of users in a particular year per 1000 inhabitants) in a population-based prescription database in North Jutland County, Denmark, during an 8 year period from 1991 to 1998.

Methods

We used the population-based Pharmaco-Epidemiological Prescription Database of the County of North Jutland, Denmark [25], initiated on 1 January 1989, to identify all lipid-lowering drug prescriptions from 1989 to 1998. The data from years 1989 and 1990 were used to ensure that our data from 1991 were from patients who were first time users of lipid-lowering drugs. The study period was from 1 January 1991 to 31 December 1998. The population of North Jutland was about 492 000 inhabitants (approximately 9% of the Danish population). The county is served by 33 pharmacies equipped with a computerized accounting system, from which data are sent to the Danish National Health Service. The latter provides tax supported health care for all inhabitants of Denmark. Apart from guaranteeing free access to general practitioners, hospitals and public clinics, the public programme has refunded 75% of the costs associated with the purchase of lipid-lowering drugs since 1994. Prior to this date, an individual application was necessary to achieve reimbursement. The information transferred to the Prescription Database from the accounting system maintained by the pharmacies includes the customers personal identification number (which incorporates date of birth), the type of drug prescribed according to the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system [26, 27], and the date of prescription [25]. The use of this 10-digit personal identification number, which is assigned to all citizens shortly after birth by the Central Population Register (CPR), ensured a complete prescription history of each participant. We identified all prescriptions on lipid-lowering drugs, i.e. statins, bile acid sequestrants, fibrates and nicotinic acid and derivatives.

Epidemiological measures

The incidence rate was defined as the number of new users of lipid-lowering drugs divided by the number of inhabitants, during that year, and the 1 year prevalence as the number of users that particular year divided by the number of inhabitants. The incidence rates and prevalence were standardized to the population in 1991 using 5 year age groups. The incidence rates and prevalence were furthermore stratified with respect to sex, age (40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70 + years) and type of drug (statins or not). The prevalence is a function of the incidence rate and the duration of treatment.

Results

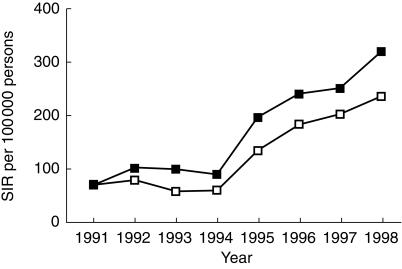

During the study period, 5935 persons received 111 236 prescriptions for drugs in the above-defined therapeutic groups, of which 83 312 (75%) were for statins. Figure 1 shows the prevalence of patients on lipid-lowering drug therapy for both sexes during the study period. There was a remarkable increase in prevalence from 1994 to 1998, from 2.8 (95% confidence intervals (CI) = 2.6, 3.0) to 9.4 (CI = 9.0, 9.7) per 1000 females, and from 3.8 (CI = 3.6, 4.1) to 12.5 (CI = 12.1, 13.0) per 1000 men. Figure 2 shows the standardized incidence rate of patients on lipid-lowering drug therapy during the study period. There was a four-fold increase from 1994 to 1998 for both females and males. Thus, the incidence increased from 59 to 237 per 100 000 person years in females and from 89 to 323 per 100 000 person years in males.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of patients (female □ and male ▪) having lipid-lowering drug therapy per 1000 persons in the county of North Jutland, Denmark in 1991–98. The 1 year prevalence shows the number of users during that particular year, divided by the number of inhabitants. The prevalence proportion was standardized to the 1991 years population using 5 year age groups.

Figure 2.

Standardized incidence rate of patients (female □ and male ▪) having lipid-lowering drug therapy in the county of North Jutland, in 1991–98. The incidence rate was defined as the number of new users divided by the number of inhabitants. The incidence rate was standardized to the 1991 years population using 5 year age groups.

The pattern of use stratified by age and gender is shown in Figures 3 and 4. Overall more males than females in all age groups were on lipid-lowering drug therapy, but the patterns were identical between the sexes. Thus the highest prevalences and incidence rates of lipid-lowering drug therapy were seen in the 60–69 years age group in both females and males. Furthermore, the marked increase in both incidence and prevalence of persons on lipid-lowering drug therapy between 1994 and 1998 was the result of an increased number of prescriptions in the age groups 50–59 years, 60–69 years and 70 + years in both females and males.

Figure 3.

Standard incidence rate of persons on lipid-lowering drug therapy with respect to age (a: females, b: males). • 40–49 years, ○ 50–59 years, ▪ 60–69 years, ▵ 70+ years.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of patients in different age groups on lipid-lowering drug therapy (a: females, b: males). • 40–49 years, ○ 50–59 years, ▪ 60–69 years, ▵ 70+ years.

After stratifying of the lipid-lowering drugs by class of drug (statins vs nonstatins), we found a 60% to 65% decrease in the incidence rate of nonstatins between 1994 and 1998 among females and males, respectively, which corresponded to a remarkable four-to five-fold increase in numbers of new patients placed on statins therapy during the same period (data not shown). In 1998 the prevalence of patients receiving prescriptions for statin drugs was 10-fold higher compared to nonstatins.

Discussion

We found marked changes in the utilization pattern of lipid-lowering drugs during the past decade. Thus the prescription of lipid-lowering drugs in the county of North Jutland, Denmark, increased four-fold between 1994 and 1998 in both females and males. This dramatic increase, which was confined to people aged 50 years or older, was caused by an increased use of statins. This increase followed the publication of the first major trial, 4S [7], to document the benefit of therapy with statins in 1994. As a direct consequence of this and other trials [8–12], the official Danish recommendations for lipid-lowering therapy have gradually been broadened throughout the 1990s. In addition, an administrative change in reimbursement practice leading to easier access to reimbursement was issued in 1999. However, this is after the study period of the present study ended.

Our study had several strengths and limitations. It was population-based and involved more than 100 000 prescriptions for almost 6000 patients. The proportion of coding errors in the prescription database is low, about 0.2% [28]. Due to the size of the dataset and the individual level of information obtained, we were able to perform time trend analysis in subgroups of patients by age and gender. Furthermore, by contrast with older studies we were able to distinguish between new and refill prescriptions [19]. However, our study was exclusively based on prescriptions, and thus we have no clinical information about the patients, e.g. the indications for which the drugs were prescribed, comorbidity, or compliance. Therefore we were unable to provide information on the relevance and effectiveness of the prescribed lipid-lowering treatment, and could not investigate whether the lipid-lowering drugs were over-or under-used in the present population.

Several recent studies have reported increased use of lipid-lowering drugs, in all cases due to the introduction of the statins [17–21, 24, 29]. The four-fold increase in our study is almost identical with the increase in the same period reported from populations in England and the US [17–19].

The prevalence of persons on lipid-lowering therapy was higher in males than females in this Danish population, which is similar to the pattern reported from Sweden [20], but contrasts with the pattern in studies from Italy and the US where the female/male ratio of lipid-lowering therapy was greater than one [20, 21].

The benefit of treating elderly persons with hyperlipidaemia remains controversial [21]. Observational studies have reported only modest associations between total cholesterol levels and the risk of CHD in the elderly [30, 31]. Furthermore, most subjects participating in the randomised trials on lipid-lowering therapy have been middle-aged Caucasian men. On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis of major trials with statins demonstrated a consistent protective effect against CHD, independent of age and sex [13]. No conclusions could be drawn concerning total mortality according age and sex. In our study, the increase in use of lipid-lowering drugs in the elderly (> 70 years) was proportionally identical to the increase among the younger patients (50–59 years and 60–69 years), and considerably larger than the increase in the youngest age group (40–49 years). This indicates that, although the scientific evidence for lipid-lowering treatment in the elderly seems less solid at present, the positive results in younger patients may eventually be extended to the elderly population. It is hoped that ongoing trials will provide additional data on the effects of lipid-lowering therapy in women and the elderly [13].

Implementation of research findings in daily clinical practice is often delayed [32, 33]. In the case of lipid-lowering therapy in general, and of statins specifically, it seems that the medical community has been well aware of this rather new treatment option. Statins have been prescribed for many new patients, as shown in the present study, since the publication of the first major trial with statins in 1994. However, there are still several major therapeutic issues. For example, previous studies have reported that screening and treatment for hyperlipidaemia is still underused (only 8% to 39% of patients with hyperlipidaemia are treated, and only 6% to 17% reach LDL-C target total) [34–36]. Moreover, lipid-lowering therapy is associated with very high discontinuation rates in routine practice outside clinical trials [23, 24, 37]. Thus continued monitoring of the utilization pattern of this new class of costly drugs remains important in order to make sure that the drug efficacy proven in trials is translated into daily clinical effectiveness.

References

- 1.National Cholesterol Education Program. Second Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel II) Circulation. 1994;89:1329–1445. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.3.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood D, De Backer G, Faergeman O, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Recommendations of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on Coronary Prevention. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:1434–1503. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1243. 10.1053/euhj.1998.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castelli WP, Garrison RJ, Wilson PWF, Abbott RD, Kalousidian S, Kannel WB. Incidence of coronary heart disease and lipoprotein cholesterol levels: the Framingham Study. JAMA. 1986;256:2835–2838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stamler J, Wentworth D, Neaton JD. Is the relationship between serum cholesterol and risk of premature death from coronary heart disease continuous and graded? Findings in 356222 primary screenees of the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) JAMA. 1986;256:2823–2828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law MR, Wald NJ, Wu T, Hackshaw A, Bailey A. Systematic underestimation of association between serum cholesterol concentration and ischaemic heart disease in observational studies: data from the BUPA study. Br Med J. 1994;308:363–366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6925.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z, Peto R, Collins R, MacMahon S, Lu J, Li W. Serum cholesterol concentration and coronary heart disease in populations with low cholesterol concentrations. Br Med J. 1991;303:276–282. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6797.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis SJ, Sacks FM, Mitchell JS, et al. Effect of pravastatin on cardiovascular events in women after myocardial infarction: the cholesterol and recurrent events (CARE) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:140–146. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. Influence of Pravastatin and Plasma Lipids on Clinical Events in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study (WOSCOPS) Circulation. 1998;97:1440–1445. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.15.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Long-term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1349–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811053391902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I,, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downs JR, Clearfield E, Weis S, et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. JAMA. 1998;279:1615–1622. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaRosa J, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1999;282:2340–2346. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.24.2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hebert PR, Graziano JM, Chan KS, Hennekens CH. Cholesterol lowering with statin drugs, risk of stroke and total mortality. An overview of randomized trials. JAMA. 1997;278:313–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Use of lipid lowering drugs for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of randomised trials. Br Med J. 2000;321:983–986. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7267.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen TR, Berg K, Cook TJ, et al. Safety and tolerability of cholesterol lowering with Simvastatin during 5 years in the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:2085–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baxter C, Jones R, Corr L. Time trend analysis and variations in prescribing lipid lowering drugs in general practice. Br Med J. 1998;317:1134–1135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7166.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Packham C, Pearson J, Robinson J, Gray D. Use of statins in general practices, 1996–1998: cross sectional study. Br Med J. 2000;320:1583–1584. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7249.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel D, Lopez J, Maier J. Use of cholesterol-lowering medications in the United States from. to 1991-1997. Am J Med. 2000;108:496–499. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00319-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magrini N, Einarson T, Vaccheri A, McManus P, Montanaro N, Bergman U. Use of lipid-lowering drugs from 1990–1994: an international comparison among Australia, Finland, Italy (Emilia Romagna Region), Norway and Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:185–189. doi: 10.1007/s002280050360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lemaitre RN, Furberg CD, Newman AB, et al. Time trends in the use of cholesterol-lowering agents in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1761–1768. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stafford RS, Blumenthal D, Paternak RC. Variations in cholesterol management practices of U.S. physicians. JACC. 1997;29:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avorn J, Monette J, Lacour A, et al. Persistence of use of lipid-lowering medications. JAMA. 1998;279:1458–1462. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen J, Vaccheri A, Andersen M, Montanaro N, Bergman U. Lack of adherence to lipid-lowering drug treatment. A comparison of utilization patterns in defined populations in Funen, Denmark and Bologna, Italy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49:463–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00192.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen GL, Sørensen HT, Weijin Z, Steffensen FH, Olsen J. The Pharmaco-Epidemiologic Prescription Database of North Jutland. Int J Risk &. Safety Med. 1997;10:203–205. doi: 10.3233/JRS-1997-10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lægeforeninggens Medicinfortegnelse. Copenhagen 1996: Lægeforeningens Forlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lægeforeninggens Medicinfortegnelse 1997. Lægeforeningens. Copenhagen: Forlag; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsen JH, Sørensen HT, Friis S, et al. Cancer risk in users of calcium channel blockers. Hypertension. 1997;29:1091–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.29.5.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacFayden RJ, Mollon I, Pringle SD, MacDonald TM. Implementation of the 4S study in first myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1996;347:551–552. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krumholz HM, Seeman TE, Merrill SS, et al. Lack of association between cholesterol and coronary heart disease mortality and morbidity and all-cause mortality in persons older than 70 years. JAMA. 1994;272:1335–1340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corti MC, Guralnik JM, Salive ME, et al. HDL. cholesterol predicts coronary heart disease mortality in older persons. JAMA. 1995;274:539–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haines A, Jones R. Implementing findings of research. Br Med J. 1994;308:1488–1492. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6942.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials and recommendations of clinical experts. JAMA. 1992;268:240–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sueta CA, Chowdhury M, Boccuzzi SJ, et al. Analysis of the degree of under treatment of hyperlipidemia and congestive heart failure secondary to coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:1303–1307. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller M, Byington R, Hunninghake D, Pitt B, Furberg CD. Sex bias and underutilisation of lipid-lowering therapy in patients with coronary artery disease at academic medical centers in the United States and Canada. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:343–347. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McBride P, Schrott HG, Plane MB, Underbakke G, Brown RL. Primary care practice adherence to National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines for patients with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1238–1244. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.11.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrade SE, Walker A, Gottlieb LK, et al. Discontinuation of antihyperlipidemic drugs – do rates reported in clinical trials reflect rates in primary care settings? N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1125–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]