Abstract

This article reviews the regulation of medical devices in the UK and Europe and compares the regulatory regime with that for pharmaceuticals. The regulation of devices follows the ‘New Approach’ policy of the EC Commission and involves more self-regulation and conformity assessment. The controls are relatively recent beginning in 1993 for Active Implantable Devices and concluding with the In Vitro Diagnostic Directive implemented in June 2000. The article describes how the directives have been implemented in the UK, the role of the Notified Bodies and the role of the Medical Device Agency (MDA) as the competent authority. In particular the Agency's compliance and standards work is described along with the strategy and post marketing surveillance and adverse incident scheme. The MDA is a key international device regulatory agency and its international role is discussed. So too is its device evaluation programme for the NHS and how this complements the work of NICE. The article also considers the future direction of the MDA and changes in the device sector.

Keywords: adverse event, conformity assessment, device regulation, medical devices, Medical Devices Agency, new approach directives, notified bodies, vigilance reporting

Introduction

Medical devices have been used to treat and diagnose disease since antiquity. There is evidence of trephination having been performed in Neolithic times and instruments have been excavated in Jericho from 2000 BC. Today devices are widely used in all branches of medicine, surgery and community care. The devices industry is a major one, with worldwide sales of more than £110 billion per year. Devices range from very simple but essential equipment through to high technology sophisticated items. Yet interestingly the formal regulation of medical devices in the UK and the European Community only began in the mid 1990s.

This article describes how devices are regulated, the role of the UK Medical Devices Agency (the MDA), how the present system has evolved and the likely future developments. It also compares the differences in the control systems for devices and pharmaceuticals.

The development of Devices Regulations in the UK and Europe

The regulation of medical devices has developed much more slowly than that of medicines, which commenced in the late 1960s as a response to the thalidomide tragedy. The formal regulation of devices in Europe only began in the mid 1990s, and followed the ‘New Approach’ concept, introduced for most consumer goods by the European Commission in 1986. The actual control of medical devices will be discussed later in this article. The difference in the initiation of controls for the devices compared with pharmaceuticals reflects several factors including differences in the type of industry (devices being predominantly engineering based), the profile for the products and the industry, the risk assessments of the products and the approach to generating efficacy and effectiveness data.

Medical device control can be traced back to the Second World War. The Ministry of Supply formed a medical equipment section to encourage UK industries to make products, which could no longer be imported. When the Ministry of Supply was disbanded, its expertise was transferred to a Technical Services Group in the Ministry of Health, which was responsible for inspecting and testing medical equipment and distributing surplus medical devices left by the US Military.

With the rapid growth in the availability and complexity of medical equipment in the 1960s product specialists were recruited to advise hospitals and to develop standards and purchasing specifications. In 1969 the defect and adverse incident reporting system and the Scientific and Technical Board (STB) of the Department of Health were established to improve the quality and safety of medical equipment along with a voluntary quality assurance system covering design and production. It was supported by compliance inspections and developed into the Manufacturers registration Scheme (MRS). At its height the MRS registered 580 manufacturing sites worldwide. The scheme was disbanded in June 1998 when the Medical Device Directive 93/42 became fully operational. The STB also ran a medical device evaluation programme to provide the NHS with independent advice about the safety and performance of the equipment they intended to purchase – this evaluation programme continues to be run today by the MDA.

During the 1980s the STB became incorporated into the NHS Procurement Directorate, which was subsequently split after 5 years into two core parts, with the creation of the NHS Supplies Authority and the Medical Devices Directorate (MDD). The latter was launched as an Executive Agency of the Department of Health in September 1994 to be known as the Medical Devices Agency.

Current regulation of medical devices

The voluntary arrangements, which previously operated in the UK, have been progressively replaced by a unified statutory system for the European Union, part of the Single Market Project. The first piece of legislation was the Active Implantable Medical Devices Directorate (90/385 E.C). This covered cardiac pacemakers and other active implantables and was introduced on the 1st July 1993. The major Medical Devices Directive (93/42) covers all other devices (excluding in vitro diagnostics), with a transitional period July 1998, during which manufacturers could choose to continue to meet national requirements. The manufacturers registration scheme therefore closed at the end of this transition period. The final legislation is the In Vitro Diagnostics (IVD) Directive, introduced in June 2000 with a 3 year transitional period. This means that in vitro test kits will be regulated for the first time.

A medical device is defined as any equipment used to treat, diagnose or prevent disease. Devices range from basic equipment such as syringes, needles and blood pressure monitors through to anaesthetic equipment, surgical instruments, heart pacemakers, hip prostheses, coronary stents, catheters, therapeutic and diagnostic X-ray equipment and MRI scanners. In the UK the Devices Legislation covers more than 18 000 medical devices with sales of £3.5 billion per year. The worldwide sales are around £110 billion. In Europe the devices industry employees more than 300 000 people in 7000 medical technology businesses. The European devices market is growing around 5–8% per annum.

How are medical devices regulated in Europe?

The three Directives are based on the European Commission's New Approach [1] which is designed to protect consumers (in this instance patients) and to allow the free movement of goods. The new Approach Directives are based on the following principles; harmonization is limited to essential requirements, only products fulfilling the essential requirements may be placed on the market. The application of harmonized standards or other specifications remains voluntary and manufacturers are free to chose any technical solution that provides compliance with the essential requirements.

The system is best understood by considering the operation of the Medical Devices Directive which is the core of the legislation. It defines three categories of device, graded accordingly to the risk assessment. The essential requirements are the standards which have been met by the manufacturer for quality systems for the design, production release marketing of the product and its individual risk assessment. The level of control, supervision and the content of data to support the product depend on the categorization.

For low risk (category I) devices the manufacturer is allowed to affix a CE mark and registers the product with a national competent authority, a system of self-certification. The national agencies (such as MDA) will check through their audit and inspection programmes that the manufacturer has complied with all the requirements. Should the requirements not have been met or if a product is marketed without a CE mark, or has been incorrectly registered, then the MDA will take appropriate enforcement action.

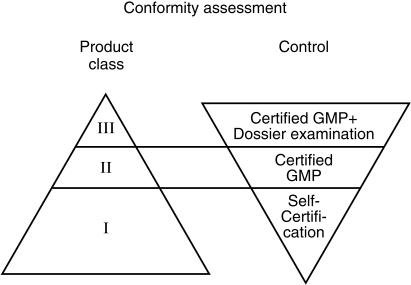

The marketing of other high-risk devices (class II and III) is controlled through so called Notified or Conformity Assessment Bodies. These are standards organizations such as BSI (British Standards Institute) or companies supervised, audited and designated in each Member State of the European Union by the relevant Devices Agency (Competent Authority) of each country. In the UK this is the MDA. The Notified Bodies are thus the premarketing assessors responsible for the higher risk devices not the National Agencies. Their activities are overseen and audited by the National Agencies. The supervision and control of medical devices is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conformity assessment-relationship between the control procedure and the product class.

The Notified Bodies check the development and the designs of the device. They also review the clinical studies, which have been undertaken, monitor the quality control procedures and the production of the device. Once the device has been granted a CE mark in one Member State, it can be marketed in all the other European Member States without further controls and no further evaluations. This is significantly different from the position for medicines. Thus if a German Notified Body approves the device, then the manufacturer can market it immediately in the UK and any other EU country.

The Directives are underpinned by standards and by guidance documents. The standards are elaborated by the European Standards Group (CEN) and many are subsequently adopted or incorporated into international standards by the ISO(International Standards Organization). There are also technical guidance documents (so called MEDDEV documents), which are generated by the European Medical Device Expert Group convened by the European Commission.

Similar control mechanisms also operate under the other two device directives, covering active implantables and in vitro diagnostics. The directives require the manufacturers to report all serious adverse incidents to the National Authorities under the so-called mandatory Vigilance scheme. This statutory scheme is supplemented in the UK by the MDA's Adverse Incident Reporting Scheme, which is described under the role of the MDA in this article.

The Directives establish a framework for the control of clinical trials for medical devices which is rather similar to that for the CTX scheme for pharmaceuticals. They also set out mechanisms for co-ordinating action between Member States through the ‘Article 7 Committee’, although to date this has been little used.

The role of the Medical Devices Agency (MDA)

The MDA is an Executive Agency of the Department of Health similar to the MCA, comprising 140 staff based at its London headquarters and also has a wheeled mobility and limb disability laboratory in Blackpool. The staff comprise engineers, biomaterial specialists, physicians, toxicologists and technologists, supported by a network of external experts and staff in the evaluation centres based in NHS and academic centres.

The Device Directives have been implemented in the UK as safety regulations under the Consumer Protection Act of 1987. The Agency is the Competent Authority for the UK and works closely with the devolved administrations.

The Agency is responsible for ensuring the compliance with the Directives and enforcing the controls. It is responsible for the post marketing surveillance of medical devices and through vigilance and Adverse Incident Schemes. The Agency has a major role to play in the development of international standards and guidance. In addition it provides policy advice to Ministers and Government on device matters and represents the UK at appropriate European and Committee. Separately the Agency has responsibilities for the approval and monitoring of clinical trials and runs two large evaluation programmes for equipment to be used in the NHS.

The Agency's Annual report [2] details how these various findings are performed. In this article the key areas will be highlighted.

As already explained, the Notified Bodies audit manufacturers of moderate to high risk devices to check compliance with Regulations and guidelines. MDA is responsible for designating and auditing the nine UK based Notified Bodies. This is done by a series of inspections to ensure that the NBs continue to meet the requirements for expertise and independence. The Notified Bodies are the linch-pin of the European system.

The Agency's auditors undertake a pro-active inspection programme for predominantly low risk devices involving almost one hundred inspections each year. In addition the Agency undertakes about 70 reactive (or for-cause) inspections each year.

The MDA has to consider and approve clinical trials to be undertaken in the UK on Medical Devices. These protocols with a technical development and safety dossier are sent to the Agency for evaluation and have to be assessed within 60 calendar days. The Agency offers feedback and advice to the industry. Recently steps have been taken to further streamline the procedure, in particular to allow parallel approval by the Agency and the relevant ethics committee.

Post market surveillance

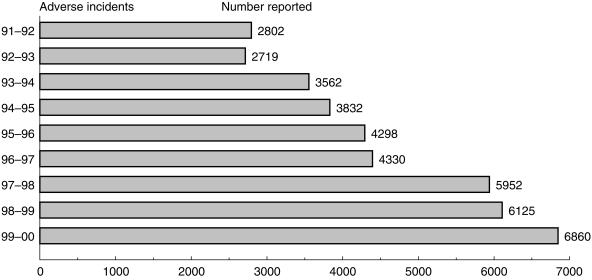

The major control point for medical devices is post market testing rather than premarketing as for medicines. This is a major activity for MDA through its two complimentary schemes of Vigilance reporting and the Adverse Incident Scheme. The first is mandatory for the manufacturer and concerns serious adverse incidents, whilst the second is voluntary and directed towards users. The Adverse Incident Scheme has many similarities with the CSM Yellow Card pharmaco vigilance scheme for medicines. The MDA receives reports from doctors, technicians, hospital engineers nurses and patients. The Agency encourages direct electronic reporting of incidents. The Agency's database permits trend analyses and can identify sectors and geographical areas of underreporting. The MDA has undertaken a series of measures to increase reporting rates and these have generated an increase of 12% per annum of reports over the last 5 years. This success is shown on Figure 2. The reporting scheme allows the Agency to monitor the safety of the device and to take any necessary corrective action. Once an incident is reported the professional staff of the MDA will investigate it, working with the hospital concerned and the manufacturer. The scheme enables MDA to prevent the recurrence of device related incidents by identifying root cause and addressing these issues with manufacturers and users. Figure 3 shows the causes of reported adverse incidents last year. During the period MDA undertook 931 in-depth investigations of the more serious incidents.

Figure 2.

The number of adverse incident reports over the period 1991–2000.

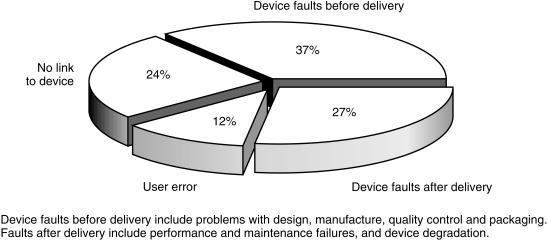

Figure 3.

The causes of adverse incidents reported during April 1999–March 2000.

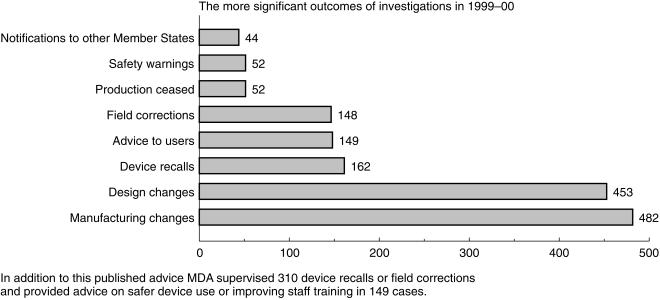

Some investigations lead to the publication of safety advice. Last year MDA published eight Advice Notices, eight Device Alerts and 36 Safety Notices. Hazard and Safety Notices require immediate action by the recipients. Safety Notices sometimes reinforce action taken by the manufacturer. The outcomes of investigations are set out in Figure 4. The Agency also supervised 310 device recalls or corrections and provided advice on the safer device use or improving staff training in 149 cases.

Figure 4.

The more significant outcomes of investigations during 1990–2000.

The Agency is striving to improve further its communication for safety issues [3]. Recent Bulletins have included topics such as Blood Pressure Monitoring Equipment, Single Use Devices and Uses of Medical Devices in Community Care.

The Agency's recommendations frequently go beyond those affecting the device itself and will include wider issues affecting the user, maintenance and training. Each NHS Trust has a Liaison Officer to act as a focal point of contact for adverse incident reporting and for the dissemination of safety information.

Earlier this year MDA introduced a weekly E-mail bulletin to Trust Chief Executives to alert them to any new Hazard Notices and other safety information on devices [4]. The Agency has continued to develop its website. Its address is http:\\www.medical-devices.gov.uk. and is well worth a visit.

The Agency also issues a single sheet publication to doctors entitled ‘One-Liners’ highlighting recent issues of concern. This year MDA plans to issue more user guidance and will be organizing various professional meetings and study days. The first study day will be on infusion pumps and is primarily directed at the nursing profession.

Evaluation programme

The MDA evaluation of equipment for the NHS is undertaken by about 80 staff working in 20 centres in hospitals and Universities. The Evaluation Service publishes reports and provides consultancy and training. The three main areas of the programme concern pathology, diagnostic imaging and acute medical services prioritized to meet the Government's health care priorities. There is a separate programme on the evaluation of disability equipment and also on the evaluation of wheelchairs. There are also three programmes concerning cancer screening equipment. The MDA works closely with NICE and its Scottish equivalent (HBTS) to ensure that the programmes are complimentary. MDA's programme does not address cost-effectiveness. Rather it provides authoritative and independent advice to NHS purchasers on the performance and functionality of available equipment which should permit an informed selection to be made of the most appropriate equipment to meet the demands of the particular institutions. The MDA holds regular formal liaison meetings with NICE to discuss emerging technologies.

International functions

The MDA plays a leading European role and has been in the vanguard of change in the EC. The devices sector has also developed a similar organization to the pharmaceutical ICH (International Conference on Harmonization) which is the Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF), this is at an earlier stage of development than the ICH and is less formalized. Its recent activities have been in the areas of device nomenclature and post marketing surveillance and guidance.

Comparison with pharmaceutical authorization procedures

The control of medical devices is very different from that of pharmaceuticals. This partly reflects the differences between the industries and the products. Devices are regulated as engineering products and this reflects the shorter development times for the product, the shorter product life span and the difficulties in undertaking major clinical studies in some areas before marketing. The life span of a device product is typically 18 months compared with 10 years or more for a pharmaceutical.

The New Approach Directives place a much greater emphasis on self regulation. The regulatory approach is therefore based on conformity assessment and post market surveillance. Indeed it can be argued that the control point for devices is post marketing whereas for medicines it is premarketing supplemented by phase IV studies. As always such generalizations are only partly true, nevertheless the recent debates over hip prostheses has illustrated some of the difficulties in obtaining trial data before authorization.

Randomised controlled clinical trials are seen much less for devices than for pharmaceuticals and when performed will usually involve comparator therapies. Studies include smaller numbers of patients to envaluate short-term efficacy with observational extensions to monitor safety. Conformity studies are rare and are often powered for safety rather than efficacy. Many manufacturers have sought to support their devices with reference to published data and then demonstrating conformity or similarity to the marketed one. These approaches have arisen because of the economics of the device sector and the importance of the user and safety problems which often relate to very long-term issues. Some of the studies have been less rigorous than those demanded for pharmaceuticals but it has to be recognized that there are practical difficulties in generating the type of data often seen from a pharmaceutical product. Almost all pharmaceuticals will have extensive clinical data supporting them, but this is not the case for devices, where only the higher risk devices are likely to have significant clinical data.

For high risk devices, there are greater requirements for toxicological and clinical data but these will be evaluated by the Notified Bodies not the MDA. The single market approach is more evident for devices since the certification is performed once only for the whole of European market. In effect this is automatic mutual recognition. There is a safeguard clause, which Member States can invoke if evidence of a major public health concern is identified.

The post market surveillance approach by MDA has many similarities to that undertaken by MCA for medicines. However, the range of reporters is much wider for devices and attributing causality can be more complex since issues of user error, maintenance and compliance have to be addressed in addition to device design and failure. MDA advice is directed more frequently to the NHS as well as to health professionals.

The greatest similarities are in the areas of inspection, enforcement and clinical trial controls. At the international level the pharmaceutical controls are more harmonized between Europe and the FDA in America. In the device sector, the FDA operates a premarketing approach regulatory system for higher risk (class II and III) devices, which is much closer to that for pharmaceuticals. Within Europe many agencies have combined responses for pharmaceuticals and devices whereas in the UK these are two distinct agencies.

Should a manufacturer make a significant change to the product then additional supportive data has to be supplied to the Notified Body for evaluation and approval. Devices are not subject to a 5 yearly review as pharmaceuticals are. Rather they are reassessed if a safety issue emerges. Each product will have a ‘user leaflet’ which is usually aimed at the professional user, so is more like an SPC (Summary of Product Characteristics) for a pharmaceutical product. The MDA monitors the advertising and promotion of devices with powers to take action under the Consumer Protection Legislation.

The medical device/medicinal product interface

The borderline between medical devices and medicinal products can be a difficult one, especially with recent developments in technology. When considering whether a product is a medical device or a medical product, the intended purpose of the product taking into account the way the product is presented has to be considered along by which the principal intended action is to be achieved. For a medical device, the principal intended action is typically fulfilled by physical means whilst for a medicine, the principal intended action is achieved by pharmacological, immunological or metabolic means. When there is significant doubt about the approval it is usual to adopt the regulatory scheme which gives the higher level of health protection. In the diagnostic field, in vitro agents are medicines whilst in vivo diagnostics are controlled as devices.

Drug-device combinations are another significant area. Drug delivery systems are regulated as devices. Drug-device combinations which are single integrated products, intended exclusively for use in given combinations and are not reusable, are regulated as medicines but the essential requirement of the Medical Device directive apply to the device related features. Thus a new aerosol device with a leukotriene antagonist for asthma will be regulated as a medicine but the device component will have to meet all the device requirements even if it is not separately marketed. In practice the MCA will readily seek the advice of the MDA on the device components. For those devices, which incorporate, as an integral part a substance which, if used separately, may be considered to be a medical product, then this is classified as a category III Device and the Notified Body has to consult a drug regulatory authority within the EU, and not necessarily the country which was the Reference Member State for the medicine. The medicines agency will advise the Notified Body on the safety of the medical agent and the evidence supporting its use in the device. Examples are heparin-coated catheters, steroid tipped pacing wires and antibiotics incorporated into devices.

The future

The regulation of medical devices is still evolving. This is to be expected since the regulations and relatively new. Indeed the major directive has only been fully operational for 2 years and the in-vitro diagnostics directive has only just recently begun its transitional period. The regulations have largely worked satisfactorily and much better than many had predicted. However, some problems have been identified leading some to call for the creation of a European Devices Agency. The UK does not currently support the call for such an institution but does believe that some re balancing and refocusing of the Device Directives is required. The UK has suggested that this is a good time to evaluate the operation of the regulations. In particular there is a need to consider increasing the risk category for many implants, subjecting them to closer scrutiny. There is perceived to be a need to increase European co-operation. The UK has also called for the creation of a European group to over see the work of the Notified Bodies. There has been considerable support for this concept of a Notified Body oversight group. Finally the UK has called for an improvement in the production of standards and guidelines, with the provision of more detailed premarketing requirements. It is felt that such changes will increase public health protection and enable the regulations to cope with the expansion of the EU and the increasing complexity of new devices.

Within MDA a number of strategic initiatives are being pursued. These will include a strategy to further increase adverse incident reporting, enhancing communications including direct E-mail to health care professionals and the establishment of a new advisory committee for devices (Committee on the Safety of Devices). There are also a series of quality assurance initiatives and outcome analysis programmes under development.

Conclusions

This article has reviewed the regulation of medical devices in the UK and Europe. There are interesting comparisons and differences between device and pharmaceutical controls. There are perhaps, lessons for both sectors to learn from each other. Developments with tissue products and theranostics will require increasingly close working between the two sectors. The profile of the devices sector is set to increase as exciting new products emerge harnessing recent developments in biomaterial science, microelectronics, information technology and genomics. These new products will have the potential to improve significantly patient well being but will need good regulatory control to maximize the benefits. This is an exciting and challenging period in the device sector.

References

- 1.European Commission. Guide to the implementation of directives based on the New Approach and the Global Approach. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the EC; 2000. ISBN 92–828–7500–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.MDA Annual Report and Accounts 1999–2000. 2000. The Stationary Office. ISBN 0–10–556874–0.

- 3.MDA Business Plan 2000–2001. 2000. (available on request from MDA or on the http://www.medical-devices.gov.uk)

- 4.MDA Directives Bulletin No4. Conformity Assessment Procedures. 1999. available on request from MDA or on http://www.medical-devices.gov.uk.