Abstract

Aims

To study the population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral etoposide in patients with solid tumours.

Methods

A prospective, open label, cross-over, bioavailability study was performed in 50 adult patients with miscellaneous, advanced stage solid tumours, who were receiving oral (100 mg capsules) etoposide for 14 days and i.v. (50 mg) etoposide on day 1 or day 7 in randomised order during the first cycle treatment. Total and unbound etoposide concentration were assayed by h.p.l.c. Population PK parameters estimation was done by using the P-Pharm software (Simed). Haematological toxicity and tumour response were the main pharmacodynamic endpoints.

Results

Mean clearance was 1.14 l h−1 (CV 25%). Creatinine clearance was the only covariable to significantly reduce clearance variability (residual CV 18%). (CL = 0.74 + 0.0057 CLCR; r2 = 0.32). Mean bioavailability was 45% (CV 22%) and mean protein binding 91.5% (CV 5%). Exposure to free, pharmacologically active etoposide (free AUC p.o.) was highly variable (mean value 2.8 mg l−1 h; CV 64%; range 0.4–9.5). It decreased with increased creatinine clearance and increased with age which accounted for 9% of the CV. Mean free AUC p.o. was the best predictor of neutropenia. Free AUC50 (exposure producing a 50% reduction in absolute neutrophil count) was 1.80 mg l−1 h. In patients with lung cancer, the free AUC p.o. was higher in the two patients with responsive tumour (5.9 mg l−1 h) than in patients with stable (2.1 mg l−1 h) or progressive disease (2.3 mg l−1 h) (P = 0.01).

Conclusions

Exposure to free etoposide during prolonged oral treatment is highly variable and is the main determinant of pharmacodynamic effects. The population PK model based on creatinine clearance is poorly predictive of exposure. Therapeutic drug monitoring would be necessary for dose individualization or to study the relationship between exposure and antitumour effect.

Keywords: cancer, etoposide, haematological toxicity, pharmacodynamics, population pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Population pharmacokinetics (PK) allows the study of the relationship between physiological measures (i.e. age, glomerular filtration, performance status) and the pharmacokinetic parameters. Ideally, large sets of pharmacokinetic data gathered in patients with heterogeneous characteristics are necessary for population PK analysis. In the field of anticancer chemotherapy, population PK analysis has been used for a few drugs such as taxotere, EO9, mitoxantrone, epirubicin and recently also for etoposide [1–5]. The population PK approach can be useful tool to study drug pharmacodynamics and eventually to individualize therapy.

The optimal or target drug exposure is unknown for most anticancer drugs [6] but there is a clear relationship between systemic exposure and toxicity of several anticancer drugs [7–9]. For etoposide, a topoisomerase II inhibitor, haematological toxicity is closely related to unbound drug exposure [10, 11]. Joel et al. [12] hypothesized the existence of a therapeutic window, but further studies are needed to better define the therapeutic concentration or exposure to etoposide.

Etoposide is used to treat a variety of solid tumours and haematological malignancies [13–17]. Its efficacy is dose-schedule dependent, the best responses being observed with prolonged exposure [18]. The oral bioavailability of etoposide is good (about 50%) and the oral route allows daily administration [19]. Prolonged oral etoposide therapy has been used in our institution for the palliative treatment of solid tumours (such as hepatocellular carcinoma and lung cancer) when conventional treatments are not very effective or fail.

In this paper, we have analysed the pharmacokinetic data from 50 patients treated with prolonged oral etoposide using population pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) methods. Since etoposide is highly plasma protein bound [11, 20], particular attention was given to the PK and PD of unbound etoposide.

Our objectives were to describe the interpatient variability in drug exposure in patients treated with prolonged oral etoposide, to measure the influence of patient characteristics on etoposide disposition using population pharmacokinetics and to investigate the relationships between drug exposure and its toxic and therapeutic effects using population pharmacodynamics.

Methods

Study design

PK and clinical data were prospectively collected in an unselected, heterogeneous population of patients treated with prolonged oral etoposide. There were no exclusion criteria on the basis of patients' characteristics, tumour type, previous treatment or the presence of detectable disease. According to institutional protocols, oral etoposide was used in patients for whom standard treatment failed or was not feasible i.e. hepatocarcinoma, lung cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer, carcinoma of unknown origin. The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee and patients gave informed consent to the study. All patients treated with prolonged oral etoposide between 1994 and 1998 were recruited to the study.

Patients

We studied 50 patients treated with daily oral etoposide and who had multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 17), advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer (n = 19), gastric cancer (n = 5), breast cancer (n = 6) or miscellaneous tumours (n = 3) (Table 1). Ten patients with hepatocellular carcinoma had been pretreated by transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), while the others were chemo-naive; 11 lung cancer patients were pretreated with one regimen of chemotherapy (vinorelbine: 6 cases; platinum based regimen: 3 cases; other: 2 cases). All breast cancer patients had been pretreated with an anthracycline-based first-line regimen, four of them had failed second and third line treatment (vinorelbine, CMF). All patients with gastric cancer had been pretreated with one regimen of chemotherapy (platinum and fluorouracil, EO9) and two patients with adenocarcinoma of unknown origin had been pretreated with a platinum-based regimen. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated by determination of creatinine clearance using the method of Jelliffe [21]. Liver function was assessed by biochemical parameters (bilirubin, ASAT, ALAT, γGT, albumin) and a quantitative liver function test (the MEGX test) based on the formation of the lignocaine metabolite. The metabolism of lignocaine is hepatic and its main metabolite, monoethilglycine xylidide (MEGX), is the product of oxidative N-dealkylation by cytochrome P450 CYP3A4. No patients were excluded and no dose modifications were made.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients treated with daily oral etoposide (median-range).

| Tumour type Number of patients (females) | Lung carcinoma n = 19 (2) | Hepatocellular carcinoma n = 17 (1) | Gastric cancer n = 5 (3) | Breast cancer n = 6 (6) | Others n = 3 (1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 68 (54–80) | 65 (52–83) | 67 (60–78) | 63 (50–72) | 71 (68–73) |

| Performance status | 2 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (2–3) | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–2) |

| Pretreatment with 1 (2) regimens of chemotherapy | 11 (0) | 10 (0) | 4 (0) | 6 (4) | 2 (0) |

| Bone metastases | 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 |

| Baseline WBC (103/mm3) | 9.1 (6.8–17.0) | 6.0 (2.8–10.6) | 8.3 (4.3–14.0) | 7.0 (3.5–12.0) | 6.9 (5.7–8.2) |

| Creatinine clearance (ml min−1) | 66 (33–118) | 78 (30–121) | 55 (37–75) | 72 (22–113) | 44 (42–83) |

| Albumin (g dl−1) | 4.3 (3.6–4.9) | 3.8 (3.3–4.8) | 4.2 (3.5–4.7) | 3.8 (3.3–4.6) | 4.2 (3.5–4.6) |

| Bilirubin (mg dl−1) | 0.6 (0.5–1.1) | 1.9 (0.5–5) | 0.8 (0.6–1) | 0.7 (0.5–0.9) | 1 (0.9–2.7) |

| MEGX test (ng ml−1) | 61 (22–89) | 38 (10–70) | 49 (34–62) | 76 (30–160) | 81 (26–93) |

Treatment and sampling schedule

Patients received a fixed 100 mg dose of etoposide as a soft gelatin capsule (Vepesid, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Latina, Italy, or Lastet, Pharmacia & Upjohn, Milano, Italy), daily for 14 days every 3 weeks. The drug was administered on an empty stomach, in the morning, with 150 ml of tap water under the supervision of the research nurse. One oral dose was replaced by a 50 mg short (1 h) i.v. infusion on day 1 or day 7. The day of the i.v. dose (day 1 or day 7) was randomised. On day 6 no treatment was administered to allow for a 48 h wash-out before the second part of the pharmacokinetic study. Etoposide was given as a single agent, without other cytotoxic drugs. Blood counts were monitored weekly and the treatment would have been stopped for haematological toxicity greater than or equal to G3.

Plasma samples were drawn during the first cycle of treatment on day 1 and day 7 at the following times: before drug administration and 1, 2, 4, 6 and 24 h post-dose. On day 10, whenever possible, the pharmacokinetic study was repeated using a limited sampling schedule (at 0, 1 and 4 h after oral drug administration) [22]. However, since pharmacokinetics were evaluated in patients without the drug washout on the previous day, unlike study days 1 and 7, and since this involved limited heterogeneous sampling, we considered these data inadequate to quantify precisely intrapatient variability and they were used only in the model fit.

Clinical data collection

Complete blood counts were drawn weekly to assess haematological toxicity. Non haematological toxicity was recorded using WHO criteria at the end of each cycle by patients' report and physical examination. Tumour response was assessed in patients with evaluable disease using the WHO response criteria. The baseline measurement of tumour size by CT-scan or ultrasound was repeated after the second and fourth cycle. Partial response (PR), is defined by a more than 50% decrease in tumour size, stable disease is the absence of new lesion, and no progression of any lesion by more than 25%; progressive disease, is defined as any new lesion or an increase in tumour size of more than 25%.

Compliance was assessed at the end of each cycle by patient's report and capsule count.

Drug assay

The total plasma concentration of etoposide was determined in all samples by h.p.l.c. The unbound drug fraction (fu) was determined by ultrafiltration of the Cmax sample. fu determined in additional samples showed a coefficient of variation < 20%, suggesting that a single fu determination in the sample at Cmax is representative of protein binding in all samples. Briefly, sample preparation involved ultrafiltration using a Centrifree® device for 30 min at 2000 g and extraction with chloroform. Isocratic separation was performed with a µ Bondapack phenyl analytical column. Fluorimetric detection was used at excitation and emission wavelengths of 288 and 328, respectively. The assay was validated in the range 0.05–1 µg ml−1 for unbound drug, and 0.2–10 µg ml−1 for total plasma concentration. Intra-assay coefficients were 11% at 0.06 µg ml−1 and 5% at 0.4 µg ml−1 A full description of the method and its validation can be found elsewhere [23]. The free fraction fu evaluated by ultrafiltration was highly correlated with the values obtained using conventional equilibrium dialysis (r = 0.825, P < 0.001, n = 12, mean relative error < 6%).

Pharmacokinetic analysis

The pharmacokinetic analysis was performed using the population PK-PD software P-pharm (Simed, Creteil, France). P-pharm utilizes an EM algorithm for the population parameter estimations. In step E (conditional expectations), individual parameters in the model were estimated assuming that they have a known prior distribution (mean, variance) and a known error variance. In step M (likelihood maximization), given the individual parameters computed in step E, the maximum likelihood posterior population mean and variance were computed together with the error variance. The fixed effect parameters were estimated by a linear or nonlinear regression from the covariables and the individual PK-PD parameters [24, 25].

The best fit to the data was a two-compartment linear model and initial pharmacokinetic parameter values and variances were taken from published series [26]. Systemic clearance (CL), volume of central compartment, k12 and k21 and bioavailability (F ) were estimated. We then studied the influence of the covariables (age, creatinine clearance, body surface area, bilirubin, albumin, the MEGX test) on the pharmacokinetics of etoposide by multiple linear regression. The EM algorithm was re-run to include the selected covariables, and population parameters and variance were again estimated.

The pharmacokinetic parameter that quantifies the systemic exposure (from time 0 to infinity) to the unbound drug after a 100 mg oral dose (free AUCp.o.) was calculated for each patient as the product of unbound fraction [(100–% bound)/100] and AUCp.o. [AUCp.o. = (F* Dose)/CL].

Pharmacodynamic analysis

The dose limiting toxicity of etoposide is neutropenia. The percentage of the decrease in absolute neutrophil counts (ANC) between the pretreatment and nadir values [E = 100* (baseline ANC−nadir ANC)/baseline ANC] was chosen as the pharmacodynamic endpoint. Using linear regression we looked for a correlation between E and the exposure parameters [dose/m2, AUC(0,∞)(i.v.), AUC(0,∞)(p.o.), C24, Cmax, free AUCp.o.] and the patients' characteristics (presence of bone metastases, pretreatment with myelotoxic chemotherapy, creatinine clearance, age, performance status (PS), baseline white blood cell counts (WBC)). The pharmacodynamic model was better characterized using the classical Emax function [27]. The maximal effect (Emax), was fixed at 100%. The model is described by the following equation:

| (1) |

where γ is the Hill constant indicating the steepness of the curve, AUC50 is the exposure at which 50% decrease of ANC is observed, and E is the percentage of reduction in ANC observed with the exposure AUC.

The individual and population PD parameters (γ, AUC50) were estimated using the EM algorithm without covariables. We then examined the influence of the following covariables on the Emax model: the presence of bone metastases, pretreatment with myelotoxic chemotherapy, age, performance status, baseline WBC counts.

Statistical methods

Stepwise multiple linear regression was used to study the correlation between pharmacokinetics and covariables. Analysis of variance was used to compare PK or PD parameters between groups of patients. Simple linear and nonlinear regression was used to study the correlation between the haematological toxicity and the PK-PD parameters. The tests were considered statistically significant for P value < 0.05.

Results

Pharmacokinetics

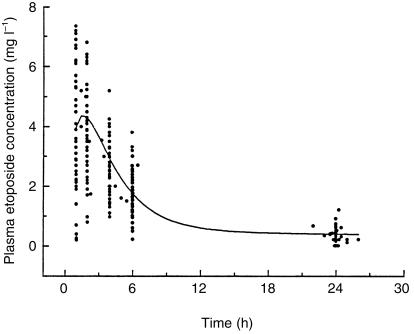

The characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 728 samples were collected from 50 patients. The population pharmacokinetic parameters and the coefficient of variation are reported in Table 2. Figure 1 shows the individual data points of the concentration vs time curve after a single 100 mg oral dose and the population fitting calculated from the population PK model. The important variability in etoposide clearance and bioavailability results in five-fold interpatient variations in drug exposure.

Table 2.

Population estimates of etoposide pharmacokinetics in 50 patients with solid tumours.

| Mean | CV (%) | Covariables | Mean with covariables | Residual CV (%) | Significant covariables | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL (l h−1) | 1.14 | 25 | CLCR, bili | 1.14 | 17 | CLCR |

| V (l) | 6.0 | 25 | %PB, BSA | 6.1 | 15 | BSA, PB |

| k12 (h−1) | 0.14 | 21 | %PB, BSA | 0.14 | 13 | PB |

| k21 (h−1) | 0.06 | 29 | CLCR | 0.07 | 20 | CLCR |

| F | 0.44 | 22 | – | 0.44 | 22 | – |

CL: systemic clearance; V: volume of distribution of the central compartment; k12 and k21 are the transfer rate constants from one compartment to the other; F: oral bioavailability; CLCR: creatinine clearance; bili: bilirubin; %PB: % of protein binding; BSA: body surface area; CV%: coefficient of variation %.

Figure 1.

Plasma concentration-time data of of total etoposide after a 100 mg oral dose. The solid line represents the best fit of the population model to the data.

Influence of renal function and ageing on clearance

The clearance of etoposide (mean value 1.14 l h−1; 25% CV) correlated positively with creatinine clearance. By including this covariable in the population pharmacokinetic model, the variability in etoposide clearance could be significantly decreased from 25 to 18%. The linear correlation between creatinine clearance and total etoposide clearance is best described by equation 2 (least square regression; r = 0.57, P < 0.001):

| (2) |

A good correlation was also found between age and creatinine clearance and is described by the equation 3 (r = 0.48; P < 0.001).

| (3) |

Both the age and the creatinine clearance correlated with total etoposide clearance. However the use of stepwise regression shows that the two phenomena are not independent (equation 3) and that age has no effect on etoposide clearance when creatinine clearance is accounted for by stepwise regression analysis. In the final population model, only the glomerular filtration rate is included since it significantly decreases interpatient variability in clearance (Table 2).

Assuming that standard 100 mg dose is adequate for patients with a CLCR=70 ml min−1 (the median value of the population), using equation 2 we calculated the CLCR for which a 25 mg dose adjustment would be necessary to correct for low or high glomerular filtration. The following theoretical dose adjustments based on the creatinine clearance would be necessary: 75 mg for CLCR < 34 ml min−1; 100 mg for CLCR 35–95 ml min−1; 125 mg for CLCR > 95 ml min−1.

Influence of hepatic function on clearance

We found a significant correlation between bilirubin concentration and total etoposide clearance. The latter was higher (2.5 ± 0.9 l h−1, n = 9) in patients with abnormal (> 1.5 mg dl−1) bilirubin concentration than in patients within the normal range (CL = 1.6 ± 0.6 l h−1; n = 41; P = 0.0004). This higher clearance was not associated with decreased protein binding 91% bound in both groups). However, the inclusion of bilirubin in the pharmacokinetic model based on creatinine clearance (equation 2) did not further improve the residual variability (CV = 17%). Thus patients with higher bilirubin concentration (≥ 1.5 mg dl−1) had higher creatinine clearance than patients with bilirubin < 1.5 mg dl−1 (80.1 ± 20.1 ml min−1 vs 67.0 ± 25.0 ml min−1, respectively). There was also no correlation between etoposide pharmacokinetics and albuminaemia, transaminase activity (MEGX test).

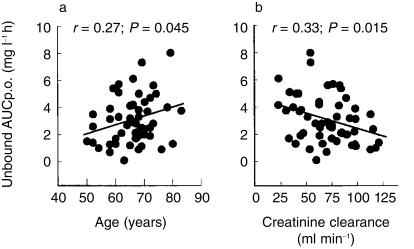

Exposure to unbound drug

The mean degree of protein binding in the population was 91 ± 5% (range 79–98). The unbound AUCp.o. was highly variable 2.8 ± 1.8 mg l−1 h (range 0.6–9.5 mg l−1 h; CV 64%). We looked for potential covariables that could be predictive of exposure to free drug. Age and creatinine clearance were found to be most important in this respect. The correlation between age and unbound AUCp.o. (Figure 2a) is described by equation 4 (least square regression: r = 0.27; P = 0.045):

Figure 2.

Relationship between exposure to free etoposide and age and creatinine clearance. The solid lines represent the best least squares fits to the data.

| (4) |

The correlation between creatinine clearance and unbound AUCp.o. (Figure 2b) is described by the equation 5 (least square regression: r = 0.33; P = 0.015):

| (5) |

Age and creatinine clearance are not independent variables (equation 3). Stepwise regression shows that age does not correlate with exposure to free drug, when creatinine clearance is accounted for. Finally, a significant correlation (r = 0.46, P < 0.001) was observed between total etoposide clearance and free etoposide clearance.

Volume of distribution

The volume of distribution of the central compartment (mean value 6.0 l; CV = 25%) was positively correlated with body surface area and unbound drug fraction. Accounting for these two covariables, the residual variability was 20%.

Bioavailability

The mean bioavailability was 45% (CV = 22%). No correlation between this parameter and any of the covariables was found. Bioavailability was higher in those patients with hepatocarcinoma than in patients with the other tumour types (59% and 38%, respectively, P = 0.02).

Pharmacodynamics

Toxicity

Nadir white blood cell (WBC) and neutrophil count were observed on day 16 (8–30) (median and range). The mean nadir WBC was 3500/mm3 (median 3400; range 300–7900); mean nadir absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was 2050/mm3 (median 1650; range 140–5600). Nadir neutrophil count was not available in six patients.

The mean decrease in ANC (%ANC) between baseline count and nadir count was 56% (median 58%; range 9–98%). The percentage ANC in patients with hepatocarcinoma was similar to that of patients with the other tumour types (50 and 59%, respectively, NS). Among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, those with or without hyperbilirubinemia had similar haematological toxicity (45 and 54%, respectively, NS).

The correlations between %ANC and the different parameters of drug exposure were investigated. Results are given in Table 3. The best correlation was found between %ANC and systemic exposure to free drug (unbound AUCp.o.). This parameter was more predictive of toxicity than simple creatinine clearance and dose/m2 (Table 3). The latter was 54.7 ± 6.1 mg m−2 and 61.3 ± 7.7 mg m−2 (P < 0.03) in the group of patients with 0–2 and grade 3–4 haematological toxicity, respectively. In contrast, mean unbound AUCp.o. was 2.48 ± 1.81 mg l−1 h and 4.03 ± 2.3 mg l−1 h (P < 0.01) in patients with 0–2 and 3–4 haematologic toxicity, respectively.

Table 3.

Correlation between haematological toxicity (% decrease ANC from baseline to nadir value) and clinical or PK parameters.

| Covariable/parameter | Correlation coefficient | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Creatinine clearance | 0.39 | 0.01 |

| Dose/m2 of etoposide | 0.45 | 0.0025 |

| C24 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Clearance | 0.36 | 0.02 |

| Unbound AUCp.o. | 0.50 | 0.0007 |

| Unbound AUCi.v. | 0.54 | 0.0003 |

No significant correlations were observed (r < 0.30) between percentage decrease ANC and pre-treatment with chemotherapy, the presence of bone metastases, age, baseline WBC, performance status, creatinine, Cmax and AUCp.o.

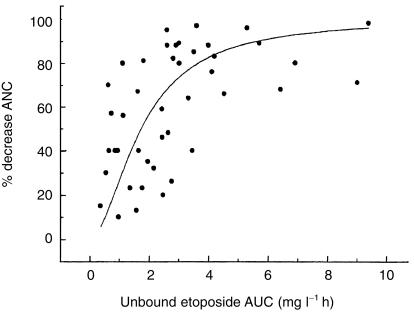

An Emax model was used to better characterize the relationship between the drug exposure and neutropenia. Emax was fixed at 100%, and the AUC50 (exposure producing a 50% reduction in ANC) was 1.80 mg l−1 h (CV27%) and Gamma (the Hill constant) was 1.47 (CV 20%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The relationship between free oral etoposide AUC and haematological toxicity. The solid line represents the best fit of the model to the Emax model to the data.

There was substantial interpatient variability in the pharmacodynamics, which was independent of the pharmacokinetics. However, none of the covariables (pretreatment, age, performance status, baseline WBC, bone metastases) was found to significantly influence the pharmacodynamic model. The difference in %ANC observed between patients with and without bone metastases (11%) was not significant (P = 0.28). However, the study was powered only to detect a 25% difference in %ANC between the two groups.

After myelotoxicity, the most frequent toxic effect was mucositis. We observed grade 1 or 2 mucositis in 12 patients, while 38 patients had no such toxicity. Exposure to free drug was 55% higher in patients with mucositis than in patients not experiencing this adverse effect (3.8±2.3 mg l−1 h vs 2.4±1.5 mg l−1 h, respectively; P = 0.02) while mean daily dose (mg m−2) was not significantly different in the two groups (60±6 mg m−2 vs 57±7 mg m−2, respectively; NS).

Antitumour effect

Patients were considered evaluable for response to therapy if they had received at least two cycles of etoposide and the subsequent tumour parameters were available. Twenty-eight patients were evaluated (15 with lung, 9 with liver, 2 with breast, 1 with gastric cancer and 1 with adenocarcinoma of unknown origin). Nineteen patients did not receive two cycles of treatment because of toxicity (10), early progression (6), or poor compliance (3). In three patients the tumour parameters were not available. We observed two partial responses in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer, 10 with stable disease (5 lung, 2 breast, 2 with liver cancer and 1 carcinoma of unknown origin) and 16 with progressive disease (8 lung, 7 liver, 1 gastric cancer).

In patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, no objective response was observed and there was no significant difference between the exposure in patients with stable or progressive disease (1.2 and 2.1 mg l−1 h, respectively, NS). In lung cancer patients, we observed that unbound AUCp.o. was much higher in the two patients with a responsive tumour (5.9 mg l−1 h) than in patients with stable (2.1 mg l−1 h) or progressive disease (2.3 mg l−1 h). (P = 0.01). The median unbound AUCp.o. in lung cancer patients (2.7 mg l−1 h) was used as a cut-off to define low or high exposure. Grade 0, 1 or 2 haematological toxicity was considered to be mild and grade 3 haematological toxicity moderate. All lung cancer patients with low exposure (n = 9) had mild toxicity, and no response to treatment. Of the nine patients with high exposure, three had moderate toxicity (one responder) and six had mild toxicity (one responder).

Discussion

In this work we studied the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of daily oral dosing with etoposide in 50 patients with solid tumours, using population PK-PD techniques. The most striking result was the large interpatient variability in drug exposure after the same daily oral dose of etoposide. In particular 15 fold differences were observed in the exposure to free, pharmacologically active etoposide. This variability is determined in part by the bioavailability, clearance and protein binding of etoposide.

By using population pharmacokinetic techniques, we have shown that the etoposide clearance is mostly influenced by glomerular filtration rate, and indirectly by ageing. The relationship between age and creatinine clearance has been widely reported [28]. However, our data show that dose adjustment based on creatinine clearance would have a marginal impact on interpatient variability, reducing exposure variability from 25 to 18%. A dose reduction of 25% would theoretically be required in patient with severe renal failure. These data confirm the conclusions of N'Guyen et al. [5] that renal function remains the only known factor that must be taken into account for etoposide dosing. However after application of our model, there remains a substantial interpatient pharmacokinetic variability, which cannot be explained by any of the covariables that we investigated.

Carboplatin is another anticancer agent undergoing renal elimination. Carboplatin dose individualization does not require the collection of individual PK data, because there is a close correlation between creatinine clearance and AUC [29, 30]. However, renal clearance is around 95% for carboplatin and only 50% for etoposide. In the present study, although the relationship between creatinine clearance and etoposide exposure was statistically significant, it explained only a part of the variability in pharmacokinetics. Thus, creatinine clearance is not sufficiently predictive to be used to individualize the dose of etoposide.

In our group of 17 patients, we found no correlation between liver function tests and etoposide clearance. These results confirm those of most authors [26, 31, 32], who found no alteration in etoposide clearance in patients with hyperbilirubinaemia. Moreover, we did not observe any enhanced haematological toxicity in patients with hepatocarcinoma, even in those with hyperbilirubinemia, as compared with patients with other tumour types. These data do not support the common recommendation for a reduction in chemotherapy dose in patients with hyperbilirubinaemia.

Serum albumin concentrations were within the normal range in our patients and thus we cannot draw definitive conclusions on the influence of abnormal serum albumin on etoposide PK/PD. Nevertheless, our data confirm previous reports on the extent of etoposide protein binding [5] indicating that it is not altered in patients with liver dysfunction. In contrast, with the hypothesis of Stewart that the high clearance of etoposide in patients with liver failure is due to a low protein binding [33], we found that patients with an abnormal bilirubin concentration and a high etoposide clearance, had normal protein binding. However, the relatively small number of patients studied did not allow us to draw definitive conclusions regarding this finding. Etoposide is bound mostly to serum albumin and to a minimal extent to α1-acid glycoprotein. In a recent paper we reported the disposition of etoposide in patients with hepatocarcinoma [34]. Comparing our data to previously published studies of etoposide pharmacokinetics in patients with altered liver function [26, 31–33], it seems that patients with mild or moderate liver dysfunction have no alterations of etoposide clearance or protein binding. However, changes in the pharmacokinetics of etoposide have been documented in patients with higher bilirubin or lower albumin concentrations [33].

The mean bioavailability of etoposide was 0.44, and no predictive covariables were identified. Saturation of etoposide absorption has been previously reported for higher dosages (300 and 400 mg orally), but absorption is linear at the dosage we used in this study (100 mg) [35]. We observed a higher bioavailability in patients with hepatocarcinoma, but the systemic exposure in these patients was similar to patients with other tumour types, because of a higher systemic clearance.

Several studies have demonstrated a correlation between the pharmacodynamic effect of oral etoposide and its plasma drug concentration. Millward et al. [36] and Miller et al. [37] reported that patients with higher etoposide AUC have an increased risk of developing WHO grade III and IV neutropenia. Sessa et al. [38] found that patients with high plasma etoposide concentrations 24 h post-dose showed a large decrease in ANC. Perdaems et al. [39] found that unbound etoposide AUC was significantly higher in the patients who had severe neutropenia. Our data show that all the pharmacodynamic effects of etoposide are influenced at least in part by the exposure to free drug, which is a better predictor of toxicity than the dose per square meter. The steepness of the concentration-response curve (Figure 3) indicates that a small increase in exposure to etoposide will result in severe neutropenia. Our data confirm the findings of Joel, who studied the pharmacokinetics and dynamics of i.v. etoposide in patients with small cell lung cancer and found that protein binding and renal function influence the toxicity of etoposide, by affecting the free drug exposure [11]. Although the model confirms the importance of free drug exposure for toxicity, there remains a substantial interpatient variability in pharmacodynamics not explained by patient characteristics such as the performance status, pretreatment with chemotherapy or baseline white blood cell counts. The influence of baseline haematological conditions on chemotherapy-induced neutropenia may become apparent in a larger study.

In our opinion preventing haematological or digestive toxicity is not the main objective of therapeutic drug monitoring. On the one hand most toxicity can be successfully managed using growth factors, antibiotics and other medical interventions. On the other hand, reducing drug exposure to prevent toxicity may increase the risk of treatment failure.

In our study etoposide was used in patients with relatively insensitive tumours, for which there was no other efficacious treatment. Not surprisingly response to etoposide was poor. Only patients with lung cancer appeared to be sensitive to etoposide. Although the limited number of patients precludes any conclusion on ‘optimal’ or therapeutic exposure, it is worth noting that the two patients who responded had the highest exposure to etoposide in the whole population. Thus, exposure to high concentrations of free etoposide seems to be an important determinant of response, regardless of toxicity. In the patients with low drug exposure, no toxicity or therapeutic response was observed and an increase in dose might have been considered. We hypothesize that improved response would have been observed if all patients with lung cancer had been exposed to high concentrations of etoposide.

In the setting of palliative chemotherapy, there is an apparent conflict between the necessity of giving potentially active doses and limiting the toxicity to maintain a good quality of life. In the two patients who had therapeutic benefit from this treatment, one had moderate toxicity and the other mild toxicity. Dosage should not be increased in all patients experiencing low toxicity, but only in those patients who achieve low concentrations of etoposide with standard doses.

If the wide interpatient variability in the pharmacokinetics of etoposide is to be reduced, adaptive control techniques using population PK parameters and individual therapeutic drug monitoring data could be used. This approach has yielded a decrease in intrapatient and interpatient variability in haematological toxicity in patients treated with i.v. etoposide [40, 41]. TDM-guided dose individualization of methotrexate, teniposide and cytarabine has permitted the safe increase drug exposure in children with leukaemia [42], resulting in a significant improvement in disease free as compared with conventional therapy.

In conclusion, system exposure to free etoposide is highly variable following oral dosing and therapeutic drug monitoring could be useful in improving drug response. Suboptimal exposure, especially in individuals with a high glomerular filtration rate and young patients, might contribute to an apparent insensitivity to chemotherapy.

References

- 1.Bruno R, Hille D, Riva A, et al. Population pharmacokinetics/ Pharmacodynamics of docetaxel in phase II studies in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:511–519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLeod HL, Graham MA, Aamdal S, Setanoians A, Groot Y, Lund B. Phase I pharmacokinetics and limited sample strategies for the bioreductive alkylating drug EO9. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1518–1522. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Launay MC, Iliadis MC, Lacarelle B. Population pharmacokinetics of mitoxantrone performed by a NONMEM method. J Pharm Sci. 1989;78:877–880. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600781020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wade JR, Kelman AW, Kerr DJ, Robert J, Whiting B. Variability in the pharmacokinetics of epirubicin: a population analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1992;29:391–395. doi: 10.1007/BF00686009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen L, Chatelut E, Chevreau C, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of total and unbound etoposide. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;41:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s002800050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratain MJ, Schilsky RL, Conley BA, Egorin MJ. Pharmacodynamics in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1739–1753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.10.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milano G, Roman P, Khater R, Frenay M, Renee N, Namer M. Dose versus pharmacokinetics for predicting tolerance to 5-day continuous infusion of 5FU. Int J Cancer. 1988;41:537–541. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910410411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jodrell DI, Egorin MJ, Canetta RM, et al. Relationship between carboplatin exposure and tumor response and toxicity in patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:520–528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoller RG, Handke KR, Jacobs SA. Use of plasma pharmacokinetics to predict and prevent methotrexate toxicity. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:630–634. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197709222971203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart CF, Arbuck SG, Fleming RA, Evans WE. Relation of systemic exposure to unbound etoposide and hematologic toxicity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991;50:385–393. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1991.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joel SP, Shah R, Clark PI, Slevin ML. Predicting etoposide toxicity: relationship to organ function and protein binding. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:257–267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joel S, O'Byrne K, Penson R, et al. A randomised, concentration-controlled, comparison of standard (5-day) vs. prolonged (15-day) infusions of etoposide phosphate in small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1205–1211. doi: 10.1023/a:1008437805286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carney DN, Keane M, Grogan L. Oral etoposide in small cell lung cancer. Seminars Oncol. 1992;19(S14):40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajani JA, Dumas P. Evaluation of oral etoposide in patients with metastatic gastric carcinoma: a preliminary report. Seminars Oncol. 1992;19(S14):45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin M, Lluch A, Casado A, et al. Clinical activity of oral etoposide in previously treated metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:986–991. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.5.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavalli F, Rozencweig M, Renard J. Phase II study of oral VP16-23 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1981;17:1079–1082. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(81)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calvert AH, Lind MJ, Millward MM, et al. Long-term oral etoposide in metastatic breast cancer: clinical and pharmacokinetic results. Cancer Treat Rev. 1993;19:27–33. doi: 10.1016/0305-7372(93)90045-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Slevin ML, Clark PI, Joel SP, et al. A randomized trial to examine the effect of schedule on the activity of etoposide in small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1333–1340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.9.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carney DN. The pharmacology of intravenous and oral etoposide. Cancer. 1991;67:299–302. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910101)67:1+<299::aid-cncr2820671315>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart CF, Pieper JA, Arbuck SG, Evans WE. Altered protein binding in patients with cancer. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;45:49–55. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1989.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jelliffe RW. Creatinine clearance: bedside estimate. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79:604–605. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-4-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gentili D, Zucchetti M, Torri V, et al. A limited sample model for the pharmacokinetics of etoposide given orally. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1993;32:482–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00685894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robieux I, Aita P, Sorio R, Toffoli G, Boiocchi M. Determination of unbound etoposide concentration in ultrafiltered plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorimetric detection. J Chromatogr B. 1996;686:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomeni R, Pineau G, Mentre F. Population kinetics and conditional assessment of the optimal dosage regimen using the p-pharm software package. Anticancer-Research. 1994;14:2321–2326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.P-pharm methodology in p-pharm user's manual 1.4. Creteil: Publishers Simed S.A; 1996. pp. 2–1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arbuck SG, Douglass HO, Crom WR, et al. Etoposide pharmacokinetics in patients with normal and abnormal organ function. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4:1690–1695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1986.4.11.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratain MJ, Mick R. Principles of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. In: Schilsky RL, Milano G, Ratain MJ, editors. Principles of Antineoplastic Drug Development and Pharmacology. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996. p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson S, Brenner BM. Effect of aging on the renal glomerulus. Am J Med. 1986;80:435–442. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90718-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calvert AH, Newell DR, Gumbrell LA, et al. Carboplatin dosage: prospective evaluation of a simple formula based on renal function. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1748–1756. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.11.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jodrell DI, Egorin MJ, Canetta RM, et al. Relationships between carboplatin exposure and tumor response and toxicity in patients with ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:520–528. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D'Incalci M, Rossi C, Zucchetti M, et al. Pharmacokinetics of etoposide in patients with abnormal renal and hepatic function. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2566–2571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hande KR, Wolff SN, Greco FA, Hainsworth JD, Reed G, Johnson DH. Etoposide kinetics in patients with obstructive jaundice. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1101–1108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.6.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stewart CF, Arbuck SG, Fleming RA, Evans WE. Changes in the clearance of total and unbound etoposide in patients with liver dysfunction. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1874–1879. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.11.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aita P, Robieux I, Sorio R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral etoposide in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;43:287–294. doi: 10.1007/s002800050897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slevin ML, Joel SP, Whomsley R, et al. The effect of dose on the bioavailability of oral etoposide: confirmation of clinically relevant observation. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;24:329–331. doi: 10.1007/BF00304768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millward MJ, Newell DR, Yuen K, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prolonged oral etoposide in women with metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;37:161–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00685644. 10.1007/s002800050382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller AA, Tolley EA, Niell HB. Therapeutic drug monitoring of 21-day oral etoposide in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1705–1710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sessa C, Zucchetti M, Torri V, et al. Chronic oral etoposide in small cell lung cancer: clinical and pharmacokinetic results. Ann Oncol. 1993;4:553–558. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perdaems N, Bachuad JM, Rouzaud P, et al. Relation between unbound plasma concentrations and toxicity in a prolonged oral etoposide schedule. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:677–683. doi: 10.1007/s002280050534. 10.1007/s002280050534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ratain MJ, Schilsky RL, Choi KE, et al. Adaptive control of etoposide dosing: impact on interpatient pharmacodynamic variability. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1989;45:226–233. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1989.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joel SP, Ellis P, O'Byrne K, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of continuous infusion etoposide in small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1903–1912. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.6.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans WE, Relling MV, Rodman JH, Crom WR, Boyett JM, Ching-Hon P. Conventional compared with individualized chemotherapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:499–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802193380803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]