Abstract

Background and purpose:

Inhibition of hepatic glycogen phosphorylase is a potential treatment for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes. Selective inhibition of the liver phosphorylase isoform could minimize adverse effects in other tissues. We investigated the potential selectivity of two indole site phosphorylase inhibitors, GPi688 and GPi819.

Experimental approach:

The activity of glycogen phosphorylase was modulated using the allosteric effectors glucose or caffeine to promote the less active T state, and AMP to promote the more active R state. In vitro potency of indole site inhibitors against liver and muscle glycogen phosphorylase a was examined at different effector concentrations using purified recombinant enzymes. The potency of GPi819 was compared with its in vivo efficacy at raising glycogen concentrations in liver and muscle of Zucker (fa/fa) rats.

Key results:

In vitro potency of indole site inhibitors depended upon the activity state of phosphorylase a. Both inhibitors showed selectivity for liver phosphorylase a when the isoform specific activities were equal. After 5 days dosing of GPi819 (37.5 μmol kg−1), where free compound levels in plasma and tissue were at steady state, glycogen elevation was 1.5-fold greater in soleus muscle than in liver (P<0.05).

Conclusions and implications:

The in vivo selectivity of GPi819 did not match that seen in vitro when the specific activities of phosphorylase a isoforms are equal. This suggests T state promoters may be important physiological regulators in skeletal muscle. The greater efficacy of indole site inhibitors in skeletal muscle has implications for the overall safety profile of such drugs.

Keywords: skeletal muscle phosphorylase; liver phosphorylase; glycogen; AMP; glucose; caffeine; GPi688; GPi819; 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol; Zucker fa/fa

Introduction

Glycogen phosphorylase (phosphorylase; EC 2.4.1.1) catalyses the phosphorolysis of the glycosidic bond in glycogen to generate glucose-1-phosphate. The kinetic properties of the enzyme have been studied since its discovery in 1936 and have revealed a complex pattern of allosteric regulation (Maddaiah and Madsen, 1966; Lowry et al., 1967; Tan and Nuttall, 1975; Stalmans and Gevers, 1981). The three isoforms of the enzyme, liver, muscle and brain, are encoded by three distinct genes. These isoforms share 80% identity at the protein level and are structurally similar. Phosphorylase exists as a dimer of two identical subunits, each subunit containing a catalytic site, an allosteric ‘I' inhibitor site, an AMP site and a novel allosteric indole site. The crystal structures of the liver and muscle isoforms have been studied extensively, and conformational changes of the enzyme in response to physiological effectors have been described in detail (Newgard et al., 1989; Sprang et al., 1991; Johnson 1992; Rath et al., 2000b; Buchbinder et al., 2001; Lukacs et al., 2006). Phosphorylase activity is regulated by phosphorylation of Serine-14 causing a conformational transition from the inactive, non-phosphorylated b state to the active, phosphorylated a state (Buchbinder et al., 2001).

Glucose, glucose-1-phosphate, glucose-6-phosphate, uridine diphosphate-glucose, N-isopropyl-p-[(125)I]iodoamphetamine (IMP), AMP, ADP and ATP have all been shown to be effectors of the enzyme. Binding of these effectors modulates the activity of phosphorylase by promoting the less active T or the more active R state. Differences in the regulation of the liver and muscle isoforms by the R state promoter, AMP were discovered in early kinetic studies with phosphorylase (Lowry et al., 1964; Kobayashi et al., 1982). Unlike liver phosphorylase b, muscle phosphorylase b can be activated by AMP. More recently, crystallographic comparisons of liver and muscle isoforms have revealed differences in the coupling between the AMP and catalytic sites that can account for the difference in sensitivity to AMP activation (Buchbinder et al., 2001). Regulation of liver glycogen phosphorylase by glucose is important in the control of hepatic glucose balance. Glucose inhibits liver phosphorylase by causing a conformational change to the T state. In hepatocytes, T state phosphorylase a is rapidly dephosphorylated to inactive phosphorylase b by protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) (Stalmans et al., 1974). The importance of glucose in regulating muscle phosphorylase is less clear. However, the mechanism of regulation by dephosphorylation of T state phosphorylase by PP1 in muscle cells is similar to that in the liver (Lerin et al., 2004).

Inhibition of glycogen phosphorylase has been proposed as a potential approach for the treatment of hyperglycaemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. In the last 10 years, compounds targeting both the catalytic and allosteric sites have been identified in the search for effective pharmacological agents (McCormack et al., 2001). One class of inhibitors binds to a novel allosteric indole site at the dimer interface. These inhibitors are efficacious at lowering blood glucose in animal models of diabetes (Martin et al., 1998). In the case of liver phosphorylase, the inhibitory effect of these indole site inhibitors in vitro was found to act synergistically with that of glucose (Martin et al., 1998). The mechanism of the synergy between glucose and the indole site inhibitors was determined from structural studies (Oikonomakos et al., 2000; Rath et al., 2000a). Indole site inhibitors bind to and further stabilize the less active T state (Oikonomakos et al., 2002). Synergy with glucose is not unique to indole site inhibitors and has been described previously for the I site inhibitor, caffeine (Kasvinsky et al., 1978). Crystal structures of glycogen phosphorylase revealed caffeine also stabilizes the less active T state conformation (Oikonomakos et al., 1992). The effect of glucose on the potency of caffeine and the indole site inhibitors indicates that inhibitor potency is dependent on the activity state of the enzyme.

An inhibitor selective for liver phosphorylase might be advantageous in the treatment of type 2 diabetes by minimizing any potential adverse effects arising from inhibiting muscle phosphorylase during exercise. Here, we investigate the potential for selectivity of indole site inhibitors between phosphorylated skeletal muscle and liver phosphorylase as a consequence of differences in regulation by AMP and glucose. We hypothesized that the overall activity state of phosphorylase a, reflecting the relative proportions of R and T states, and hence the activation state, would affect the potency of these inhibitors and offer the potential for tissue selectivity. We have used the allosteric effectors AMP, glucose and caffeine to manipulate phosphorylase a activity, thus altering the amount of phosphorylase a in the R and T states. The effect of these R and T state promoters against human recombinant skeletal muscle phosphorylase a activity has not been described previously. We then investigated the potencies of two indole site inhibitors, GPi688 and GPi819 (Figure 1), against human recombinant skeletal muscle phosphorylase a and liver phosphorylase a in the presence and absence of glucose, AMP and caffeine. Finally, we have compared the efficacy of GPi819 on glycogen content in liver and skeletal muscle of Zucker fa/fa rats. Our data indicate that potency correlates with the activation state of the enzyme and that in vitro, indole site inhibitors show selectivity for liver phosphorylase a. However, in vivo, the efficacy of GPi819 was greater in skeletal muscle than in liver. This greater efficacy cannot be easily explained by the physiological differences in glucose and AMP concentrations between liver and skeletal muscle. These results indicate that other T state promoters may be the major physiological regulators of phosphorylase activity in skeletal muscle under fed, non-exercising conditions.

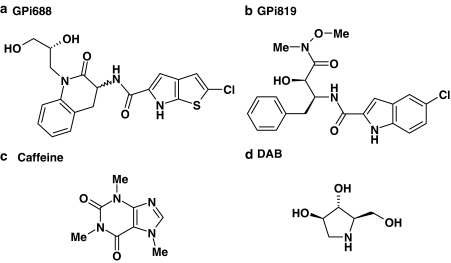

Figure 1.

(a) GPi688 (2-chloro-N-{1-[(2R)-2,3-dihydroxypropyl]-(3R/S)-2-oxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-3-yl}-6H-thieno[2,3-b]pyrrole-5-carboxamide); (b) GPi819 (N-{(1S,2R)-1-benzyl-2-hydroxy-3-[methoxy(methyl)amino]-3-oxopropyl}-5-chloro-1H-indole-2-carboxamide); (c) caffeine; (d) DAB.

Methods

Animals

Zucker (fa/fa) rats were obtained from the Animal Breeding Unit, AstraZeneca, Alderley Park, Cheshire. Animal experiments were undertaken in strict adherence to the Animals Scientific Procedures 1986 Act (UK).

Recombinant enzyme expression and purification

Recombinant human and rat liver phosphorylase and human skeletal muscle phosphorylase isoforms were expressed and purified by a modification of the method described by Luong et al. (1992). Liver and skeletal muscle phosphorylase cDNAs were cloned into pFastBac (Invitrogen, UK) and expressed in Sf+ insect cells under control of the polyhedron gene promoter. Cells expressing the skeletal muscle enzyme were harvested 48 h post-infection whereas cells expressing the liver phosphorylase were harvested 72 h post-infection. To prepare phosphorylase in the active state only, the dialysed fraction from a Cu2+ iminodiacetic acid column (Pharmacia-LKB, Sweden) was phosphorylated with rabbit muscle phosphorylase kinase using 1 μg kinase per 18 μg phosphorylase in the presence of 200 μM ATP and 3 mM MgCl2 at 30°C for 1 h. Phosphorylated phosphorylase was dialysed into 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.2 mM EDTA and further purified by applying to a Mono Q column (GE Healthcare, UK) equilibrated with buffer B (25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.5 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA). The column was washed with buffer B (10 column volumes) and protein eluted with a 0–400 mM NaCl gradient in buffer B over 30 column volumes. The fractions containing phosphorylase a were pooled and dialysed into 25 mM β-glycerophosphate (pH 6.8), 0.3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.3 mM EDTA. The pooled fractions were diluted with an equal volume of polyethylene glycol 400 and stored at −20°C.

During the preparation of this paper, methods for the expression and purification of human muscle glycogen phosphorylase for structural studies were published (Lukacs et al., 2006). Their methods are essentially the same as ours with the inclusion of additional sizing column and a 5′-AMP Sepharose column.

Dephosphorylated skeletal muscle phosphorylase b was produced by treating the phosphorylated enzyme in 25 mM β-glycerophosphate (pH 6.8), 0.3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.3 mM EDTA with PP1 at a ratio of 1:100 PP1:GPa (vv−1) at room temperature for 1 h. The enzyme was stored in the presence of PP1 in 25 mM β-glycerophosphate (pH 6.8), 0.3 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.3 mM EDTA at 4°C.

The degree of phosphorylation of the enzymes was determined by mass changes, measured by mass spectrometry (Micromass LCT, Waters, UK). Protein concentrations were measured by the Bradford assay (Bradford, 1976) using a Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, CA, USA).

Glycogen phosphorylase assays

Enzyme activity was measured in the glycogenolytic direction by the coupled enzyme reaction with a phosphoglucomutase preparation from rabbit muscle, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Maddaiah and Madsen, 1966). Reduction of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to NADH was measured either spectophotometrically or fluorometrically at 30°C in MATRIX (Matrix Technologies Corp., NH, USA) 384-well plates in a final volume of 50 μl. Fluorescence was read at 340 nm excitation/465 nm emission and absorbance was read at 340 nm on a Tecan Ultra Evolution plate reader (Tecan, UK). The reaction mixture contained 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 3.5 mM KH2PO4, plus 1 mg ml−1 glycogen, 5 mM NAD+, 0.5 mM DTT. Recombinant human phosphorylase isoforms were added at a final concentration of 8 nM. Recombinant rat liver phosphorylase was added at a final concentration of 6 nM. The coupling enzymes, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and phosphoglucomutase, were in excess at 1 and 0.0625 U per well. Enzymes were pre-incubated for 30 min with glycogen, glucose and AMP before the addition of inhibitors; 20 μl of pre-incubated enzyme was added to wells containing 10 μl inhibitor in 10% dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO), or 10% DMSO alone, and the reaction was started with the addition of 20 μl of the coupling enzymes in the HEPES buffer. Assay conditions were optimized to ensure that the reaction rate was linear with time and enzyme concentration. Glucose, caffeine, 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol (DAB) and the inhibitors GPi688 and GPi819 did not inhibit glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase or phosphoglucomutase.

The effect of glucose (0, 4, 8, 16 or 32 mM) and AMP (0–0.2 mM) on human enzyme activity and the potencies of the inhibitors, GPi688, GPi819, DAB and caffeine were determined fluorometrically. The potencies of GPi688 and GPi819 against rat liver enzyme were determined in the presence of 12 mM glucose and in the absence of AMP. Potencies are expressed as IC50 values, calculated from the hyperbolic inhibition curve-fitting model in Origin Version 7.5 (Origin Lab Co., MA, USA). The geometric mean and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated from at least three independent IC50 determinations.

Specific activities of muscle phosphorylase a and b in the presence of 0.2 mM AMP and 15 mM glucose were determined spectrophotometrically from changes in the absorbance at 340 nm on the reduction of NAD+ to NADH. The specific activity of liver phosphorylase a was determined with and without AMP at 8 mM glucose. The absorbance reading from the Tecan plate reader was corrected to a 1 cm path length using the protocol supplied by the manufacturer. An extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM cm−1 for NAD+ was used to calculate specific activities (μmol min−1 mg−1 protein). Specific activities at AMP concentrations less than 0.2 mM were calculated from the fluorescence readouts and converted to μmol min−1 mg−1 protein by the following equation.

(fluorescence at X mM AMP/fluorescence at 0.2 mM AMP) × specific activity at 0.2 mM AMP

The change in fluorescence was linear over the range of specific activities measured.

In vivo efficacy study

Tissue glycogen concentration was measured in 9- to 11-week-old male Zucker fa/fa rats dosed with either vehicle (0.25% polyvinyl pyrrolidine/0.05% sodium dodecyl sulphate) (5 ml kg−1) or vehicle+GPi819 (12.5, 37.5 or 125 μmol kg−1), p.o for 5 days. Animals were housed in pairs on a 12:12 h light cycle with free access to water and breeding diet (RM3 2.7 kcal g−1 or 14.4% kcal of fat in ration). Body weight was monitored daily at the time of compound dosing (2 h after lights on). Three days before the start of compound dosing, all animals were gavaged orally with vehicle to become accustomed to oral dosing. Twenty-four hours after the final dose, animals were culled by terminal anaesthesia with halothane and the liver, soleus and extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles removed for the measurement of tissue glycogen concentration. All tissues were weighed, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until required for analysis. Tissue glycogen concentration was analysed by potassium hydroxide digestion of tissues at 70°C followed by amyloglucosidase conversion of glycogen to glucose. The liberated glucose was measured by the addition of hexokinase and measurement of the absorbance of the NADPH generated from the subsequent reaction at 340 nm on a Multiscan Ascent (ThermoQuest, UK). Glycogen concentration in tissues was calculated as μmol g−1 wet weight tissue.

Analytical methods

The compound concentration in plasma and tissue from GPi819-treated animals was measured by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy (LC-MS). Tissue samples (approximately 100 mg) were diluted 10-fold with distilled water and homogenized using a hand-held homogenizer. Homogenate samples or calibration standards (100 μl) were vortex mixed with acetonitrile (200 μl) to precipitate the proteins, the resulting mixture was centrifuged, and the supernatant decanted before injection (10 μl) onto the LC-MS system. Separation was achieved using a Prodigy 3 μm octadecyl silane(3) 100 × 4.6 mm HPLC column (Phenomenex, Macclesfield, UK) with a water:acetonitrile:formic acid:40:60:0.2 mobile phase, coupled to a Sciex API-365 detector.

Chemicals

GPi688 (2-chloro-N-{1-[(2R)-2,3-dihydroxypropyl]-(3R/S)-2-oxo-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-3-yl}-6H-thieno[2,3-b]pyrrole-5-carboxamide) was synthesized as described in patent WO 03/074532A1 (AstraZeneca, 2003). GPi819 (N-{(1S,2R)-1-benzyl-2-hydroxy-3-[methoxy(methyl)amino]-3-oxopropyl}-5-chloro-1H-indole-2-carboxamide) was synthesized at AstraZeneca as described in patent WO 96/39385 (Pfizer, Inc. 1995). DAB was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (UK). Stocks solutions (10 mM) of GPi688, GPi819 and DAB were prepared in DMSO. Caffeine (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) was dissolved in distilled water to give a 10 mM stock solution. Rabbit liver glycogen type III, D(+)glucose, AMP, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase type IX (200–400 units mg−1), phosphoglucomutase preparation from rabbit muscle (containing α-D-glucose-1-phosphate phosphotransferase and α-D-glucose-1,6-bisphosphatase), rabbit muscle phosphorylase kinase and amyloglucosidase from Aspergillus niger were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (UK). PP1 was obtained from Upstate (UK) and hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase was purchased from Boehringer (UK).

Statistical analysis

Phosphorylase activities are quoted as the mean and s.e.mean from at least three independent experiments. The IC50 data were summarized by a geometric mean and least significant difference (LSD) bars for at least three independent IC50 determinations. Overlaying LSD bars indicate no statistical significance at the 5% level. Tissue glycogen and compound concentrations are mean and s.e.mean. Statistical comparisons were performed using group contrasts following linear modelling that correctly reflected the experimental structure of dependence (each animal furnished data for three tissues) and independence (12 animals, randomly split into three group of four).

Results

Specific activities of purified recombinant phosphorylase

Skeletal muscle phosphorylase b had negligible activity without AMP present. The specific activities of skeletal muscle phosphorylase a and phosphorylase b in the presence of 0.2 mM AMP and 15 mM glucose were 167±11 and 116±9 μmol min−1 mg−1, respectively. The specific activity of liver phosphorylase a in the presence of 0.2 mM AMP and 8 mM glucose was 274±12 μmol min−1 mg−1. Liver phosphorylase a specific activity in the absence of AMP and presence of 8 mM glucose was 109±16 μmol min−1 mg−1. There was no significant difference in the specific activities of skeletal muscle phosphorylase a in the presence of 0.2 mM AMP and 15 mM glucose, and liver phosphorylase a in the presence of 8 mM glucose alone.

The phosphorylation state of the recombinant skeletal muscle enzyme was determined by mass spectroscopy. Treatment of purified enzyme with phosphorylase kinase resulted in 100% phosphorylation and treatment with PP1 generated the fully dephosphorylated phosphorylase b enzyme. Specific activities of stored phosphorylated liver and muscle phosphorylase a remained unchanged over the time period of the investigations. The activity of dephosphorylated muscle phosphorylase b was lost on storage.

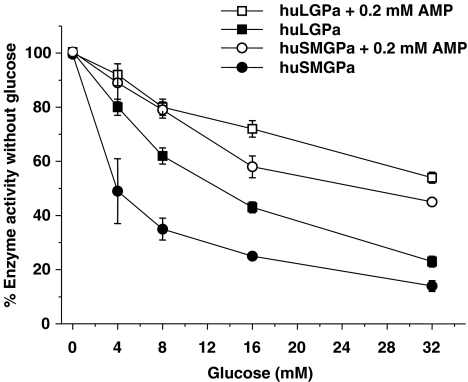

Inhibitory effect of glucose on phosphorylase a

Glucose inhibited both liver and muscle phosphorylase a in a concentration-dependent manner and the inhibitory effect of glucose was reduced by a maximally activating concentration of AMP (0.2 mM) (Figure 2). In the presence of 8 mM glucose alone, liver phosphorylase a was inhibited by 38±9%. This inhibition was reduced to 20±6% by the addition of 0.2 mM AMP. Skeletal muscle phosphorylase a was inhibited by 65±6% with 8 mM glucose alone, and this was reduced to 21±5% inhibition in the presence of 0.2 mM AMP. In 15 mM glucose, skeletal muscle phosphorylase a was inhibited by ∼75% and this inhibition was reduced to ∼35% with 0.2 mM AMP (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Glucose inhibited liver (huLGPa) and skeletal muscle (huSMGPa) phosphorylase a in a concentration-dependent manner. Phosphorylase activities were determined from the change in fluorescence in the conversion of NAD+ to NADH at 0, 4, 8, 16 and 32 mM glucose in the presence and absence of 0.2 mM AMP. Note that in the absence of glucose, the specific activities for each isoform in the presence or absence of AMP were different. Values are arithmetic mean and s.e.mean from at least three independent experiments.

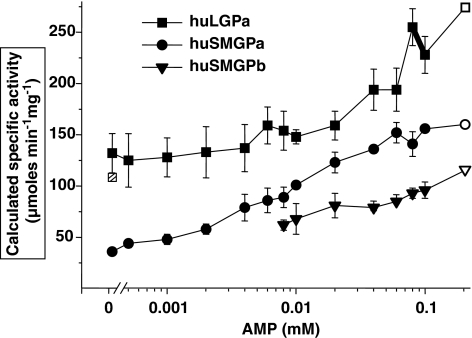

AMP activation of phosphorylase a and b in the presence of glucose

In the presence of 15 mM glucose, AMP (0.2 mM) increased skeletal muscle phosphorylase a activity by 2.4- to 4.0-fold above activity without AMP (Figures 2 and 3). Note that in Figure 3, activation by AMP is expressed as calculated specific activity at each AMP concentration. In contrast, AMP (0.2 mM) increased liver phosphorylase a activity 1.3- to 2.0-fold in the presence of 8 mM glucose. Skeletal muscle phosphorylase b in the presence of 15 mM glucose required AMP for activation and activity increased ∼2-fold as AMP concentration was increased from 8 μM to 0.2 mM. The kinetic data for liver phosphorylase a and skeletal muscle phosphorylase b (Figure 3) fitted the Michaelis–Menten equation. The KM for liver phosphorylase a with respect to AMP was 67 μM (95% CI 22–206 μM) and for skeletal muscle phosphorylase b the value was 28 μM (95% CI 7–118 μM). The change in activity of the skeletal muscle phosphorylase a with AMP was sigmoidal. The concentration estimated to give the half-maximum reaction rate was 10 μM (95% CI 3–40 μM) and a Hill coefficient of ∼1.0, indicating no cooperativity.

Figure 3.

AMP increased activity of phosphorylated skeletal muscle (huSMGPa), dephosphorylated skeletal muscle (huSMGPb) and phosphorylated liver (huLGPa) glycogen phosphorylase. Glucose was present at 8 mM with liver phosphorylase and 15 mM with muscle phosphorylase. Activities were measured as described previously for glucose inhibition. Activity is expressed as calculated specific activity from specific activity measured at 0.2 mM AMP. The measured specific activities at 0.2 mM AMP for each enzyme are shown in the figure with open symbols and were 167±11, 116±9 and 274±12, μmol min−1 mg−1 for skeletal muscle phosphorylase a, skeletal muscle phosphorylase b and liver phosphorylase a, respectively. The calculated specific activity for liver phosphorylase a without AMP was 132±32 μmol, which agreed with the measured specific activity of 109±16 μmol min−1 mg−1. The measured value is shown in the figure with the hatched box. Values are mean and s.e.mean from three independent experiments.

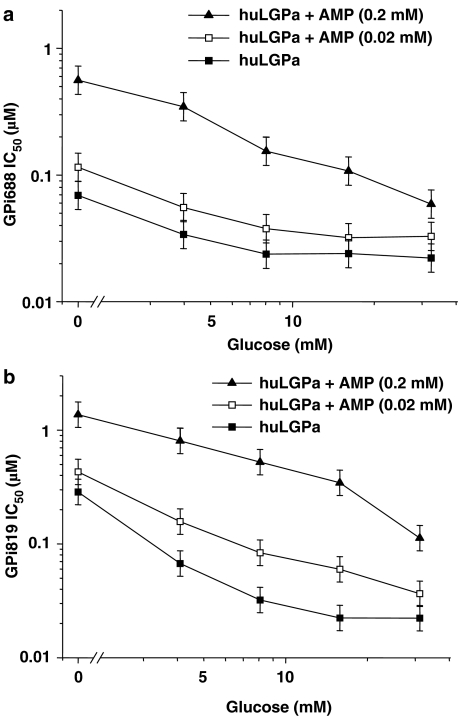

Effect of AMP and glucose on the potency of GPi688 and GPi819

We first examined the synergistic effect of glucose on the potency of GPi688 and GPi819 against liver phosphorylase a at 0, 4, 8, 16 and 32 mM glucose (Figure 4). In the absence of AMP, the potency of GPi688 and GPi819 increased three- and 10-fold, respectively between 0 and 8 mM glucose. The potencies showed no further increase at higher glucose concentrations. The synergy between glucose and inhibitor was maintained in the presence of maximally activating AMP (0.2 mM) and sub-maximally activating AMP (0.02 mM). AMP at 0.02 mM had little or no effect on inhibitor potency at each glucose concentration. AMP at 0.2 mM significantly reduced the potency of both indole site inhibitors at 0, 4, 8, and 16 mM but not at 32 mM glucose. Without glucose, the IC50 value for GPi688 decreased from 0.069 μM (95% CI 0.052–0.09 μM) to 0.56 μM (95% CI 0.429–0.732 μM) on addition of 0.2 mM AMP. Similarly, without glucose present and on addition of 0.2 mM AMP, the IC50 value for GPi819 decreased by a factor of 7.

Figure 4.

The IC50 for indole site inhibitors (a) GPi688 and (b) GPi819 decreased with glucose against phosphorylated liver phosphorylase (huLGPa) in the absence and presence of AMP. Glucose was present at 8 mM with liver phosphorylase a. The figure shows the geometric mean and LSD bars for at least three separate IC50 determinations.

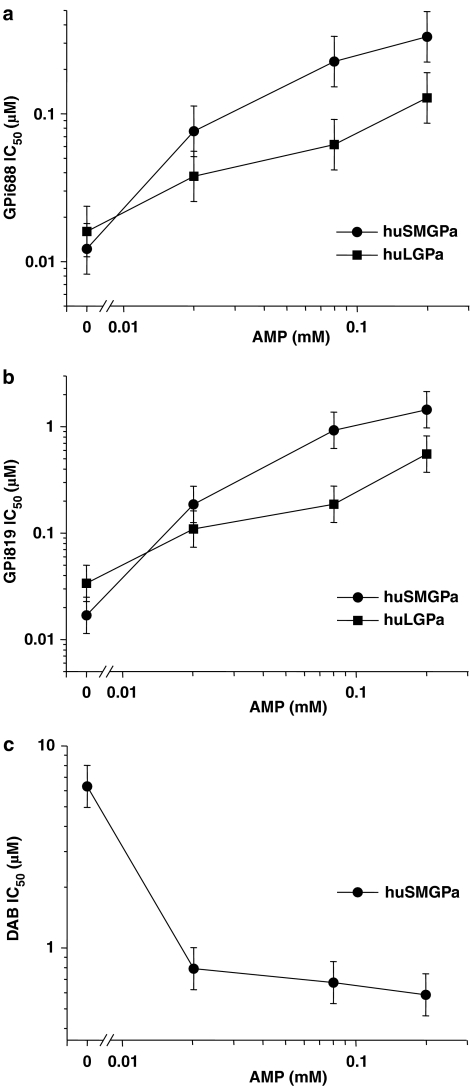

We then determined the effect of AMP on the IC50 values for GPi688 and GPi819 against both liver and skeletal muscle phosphorylase a at a single glucose concentration (Figure 5). Glucose concentrations of 8 mM for liver phosphorylase a, and 15 mM for skeletal muscle phosphorylase a, were selected for inhibitor potency comparisons. At these glucose concentrations and in the absence of AMP, the specific activity of skeletal muscle was significantly less than that of liver (P<0.05) (Figure 3). However, the IC50 values for GPi688 and GPi819 were similar against both enzymes (Table 1). In the case of GPi688, addition of 0.02 mM AMP resulted in a sixfold increase in the IC50 value for skeletal muscle phosphorylase a and hence a reduction in potency, but only a twofold difference in the IC50 value for liver phosphorylase a (Figure 5a). The maximally activating concentration of AMP (0.2 mM) caused a 28-fold increase in the IC50 value for skeletal muscle phosphorylase a and a sevenfold increase in the IC50 value for liver phosphorylase a. AMP had a similar effect on the IC50 values of GPi819 (Figure 5b). At 0.2 mM AMP, both inhibitors were less potent against skeletal muscle phosphorylase a than against liver phosphorylase a by a factor of ∼2.5.

Figure 5.

AMP reduced the potency of (a) GPi688 and (b) GPi819 against liver (huLGPa) and skeletal muscle phosphorylase a (huSMGPa), but increased the potency of (c) DAB against skeletal muscle phosphorylase a (huSMGPa). Glucose was present at 8 mM with liver phosphorylase a and 15 mM with muscle phosphorylase a. The figure shows the geometric mean and LSD bars for at least three separate IC50 determinations.

Table 1.

Potency of GPi688 and GPi819 against human and rat phosphorylase isoforms in the presence of glucose

| GPi688 | GPi819 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose (mM) | IC50 (μM) | 95% CI | IC50 (μM) | 95% CI | |

| huLGPa | 8 | 0.019 | (0.011–0.034) | 0.034 | (0.024–0.047) |

| ratLGPa | 12 | 0.061 | (0.034–0.110) | 0.062a | |

| huSMGPa | 15 | 0.012 | (0.007–0.021) | 0.017 | (0.007–0.044) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

IC50 values were calculated from at least three independent experiments and expressed as geometric means with 95% CI, unless otherwise indicated.

The potency of GPi819 against ratLGPa was determined in two independent experiments. The individual IC50 values were 0.034 and 0.112 μM.

As noted earlier, the specific activities of the two isoforms were similar when glucose was present at 8 mM without AMP, for liver phosphorylase a, and at 15 mM with 0.2 mM AMP for muscle phosphorylase a. At these comparable specific activities, GPi688 was 17-fold more potent, and GPi819 was 50-fold more potent against the liver isoform (Figure 5a and b). The GPi688 IC50 values for liver and muscle phosphorylase a, respectively, were 0.016 μM (95% CI 0.010–0.026 μM) and 0.332 μM (95% CI 0.204–0.540 μM), and for GPi819, the IC50 values were 0.034 μM (95% CI 0.024–0.047 μM) and 1.448 μM (95% CI 0.824–2.542 μM).

Inhibition of recombinant human skeletal muscle phosphorylase a by DAB

In the absence of AMP, the potency of DAB was 6.3 μM (95% CI 4.4–9.0 μM). In the presence of 0.2 mM AMP, the IC50 value for DAB decreased to 0.59 μM (95% CI 0.55–1.13 μM) and did not change significantly at low AMP (0.02 mM) (Figure 5c).

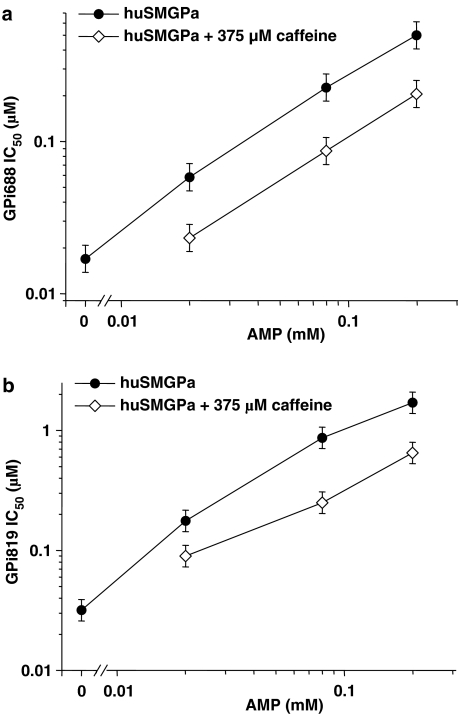

Effect of caffeine on potency of GPi688 and GPi819 against skeletal muscle phosphorylase a

We used caffeine in combination with AMP and glucose to determine the effect of ligands bound at the catalytic, AMP and I sites, on the potency of indole site inhibitors against skeletal muscle phosphorylase a. We first examined the effect of AMP and caffeine on the individual phosphorylase a isoforms. In the presence of 0.2 mM AMP, the IC50 value for caffeine was 360 μM (95% CI 250–500 μM). The potency did not alter with either 0.02 or 0.08 mM AMP (data not shown). In the absence of AMP, the potency of caffeine was 92 μM (95% CI 31–274 μM). Caffeine (375 μM) in combination with glucose inhibited skeletal muscle phosphorylase a activity, but did not prevent activation of the enzyme by AMP (data not shown).

IC50 values for GPi688 and GPi819 were then determined in the presence of AMP (0.02, 0.08 and 0.2 mM), glucose (15 mM) and caffeine (375 or 750 μM). The combination of caffeine and glucose resulted in a two- to threefold increase in potency at each AMP concentration (Figure 6). Both caffeine concentrations were equally effective in increasing the potencies of GPi688 and GPi819 against AMP-activated skeletal muscle phosphorylase a. In the absence of AMP, 375 μM caffeine with 15 mM glucose inhibited the activity of skeletal muscle phosphorylase a by 80–90% and IC50 values for GPi688 and GPi819 could not be calculated accurately.

Figure 6.

Effect of caffeine (375 μM) on the potency of (a) GPi688 and (b) GPi819 against skeletal muscle phosphorylase a (huSMGPa) in the presence of increasing AMP and 15 mM glucose. The figure shows the geometric mean and LSD bars for at least three separate IC50 determinations.

Inhibition of recombinant rat liver phosphorylase a by GPi688 and GPi819

The potencies of GPi688 and GPi819 against recombinant rat phosphorylase were determined in the presence of 12 mM glucose and absence of AMP. As shown in Table 1, in the case of each inhibitor, the difference between the IC50 values against rat and human liver phosphorylase a was <3-fold. This was not considered pharmacologically significant.

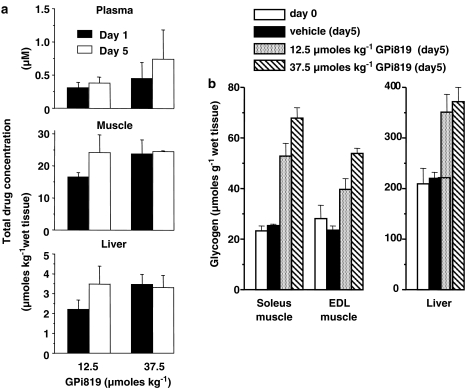

In vivo concentrations of GPi819 and efficacy on muscle and liver glycogen storage

To investigate the efficacy of indole site inhibitors in vivo, GPi819 was administered orally for 5 days to free-feeding male Zucker (fa/fa) rats at a once-daily dose of 12.5 or 37.5 μmol kg−1. Total compound concentrations were measured at the dose interval in plasma, liver and gastrocnemius muscle on days 1 and 5. There was no significant increase in plasma or tissue compound concentration between the two dose levels at either time point (Figure 7a). Following 37.5 μmol kg−1, the plasma concentration of GPi819 was 0.5±0.24 and 0.7±0.44 μM on days 1 and 5, respectively, suggesting that compound distribution was at steady state at day 5. Steady-state compound distribution was also observed in plasma at the lower dose of 12.5 μmol kg−1. After 5 days of oral dosing at 37.5 μmol kg−1, total GPi819 concentrations in the liver and muscle were 3.3±0.6 and 24±0.3 μmol kg−1 wet weight, respectively. At the lower dose of 12.5 μmol kg−1, total GPi819 concentrations in liver and muscle were 3.5±0.9 and 24±6.0 μmol g−1 wet weight, respectively.

Figure 7.

In vivo efficacy of GPi819 on skeletal muscle and liver glycogen content in Zucker (fa/fa) rats. (a) Total compound concentration in plasma, muscle and liver at the dose interval on days 1 and 5 of treatment. (b) Glycogen content in liver and muscle tissue before treatment at day 0, and after 5 days oral treatment with vehicle (0.25% polyvinyl pyrrolidine/0.05% sodium dodecyl sulphate) alone, or with vehicle+GPi819 at 12.5 or 37.5 μmol kg−1. Animals were housed in pairs on a 12:12 h light cycle with free access to water and breeding diet. Animals were gavaged for 3 days with vehicle (5 ml kg−1), followed by 5 days treatment with vehicle±GPi819. The values shown are mean±s.e.mean (n=4).

To determine in vivo efficacy, the glycogen content of liver, soleus muscle and EDL muscle was measured in the same GPi819-treated animals. Glycogen content in tissue from the vehicle-dosed animals was not significantly different between days 0 and 5 (Figure 7b). After 5 days dosing of GPi819 at 12.5 and 37.5 μmol kg−1, liver glycogen content was 1.6- and 1.7-fold greater than the glycogen content in the vehicle-dosed animals. At the dose of 12.5 μmol kg−1, EDL and soleus muscle glycogen content was increased 1.7- and 2.0-fold, respectively. At 37.5 μmol kg−1, EDL and soleus muscle glycogen content was increased 2.3- and 2.6-fold and the fold increase in glycogen content in soleus muscle was significantly greater than the fold increase in liver (P<0.05). The data show a similar trend for EDL muscle, although did not reach statistical significance. As part of the same study, a separate group of rats was dosed with 125 μmol kg−1 GPi819 for 5 days. In these animals, liver glycogen content was increased by 2.2-fold to 485±35 μmol glycogen g−1 wet weight tissue. Glycogen content in EDL muscle was increased by 5.2-fold (124±7 μmol glycogen g−1 wet weight tissue) and soleus muscle by 3.7-fold (95±3 μmol glycogen g−1 wet weight tissue). The fold increase in glycogen content in both muscle subtypes was significantly greater than in liver (EDL, P<0.0001; soleus, P<0.01).

Discussion

Our aim was to investigate potential isoform selectivity of two indole site inhibitors, GPi688 and GPi819, against skeletal muscle and liver phosphorylase a. Glycogen phosphorylase is regulated by a complex interplay between many allosteric effectors altering the activity state of the enzyme. In generating the in vitro profile of indole site inhibitor potency, we chose to focus on the R state promoter AMP, and T state promoters glucose and caffeine, to modulate phosphorylase a activity state. Other known effectors were held constant, such as inorganic phosphate (3.5 mM), or omitted, such as ADP and ATP.

AMP is the major regulator of rabbit-isolated muscle enzyme, activating the a and b form by different degrees. The b form requires AMP for activity and the a form is further activated by AMP (Newgard et al., 1989; Johnson 1992; Oikonomakos et al., 1992). AMP concentrations ranging from 0.45 μM to 0.1 mM have previously been reported to activate rabbit skeletal muscle phosphorylase a by three- to fourfold in the presence of known allosteric effectors (Kasvinsky et al., 1978; Rush and Spriet, 2001). In the presence of glucose, human recombinant skeletal muscle b used in our studies required at least 8 μM AMP for significant activation and the phosphorylated a form was further activated by 4 μM AMP. We observed a fourfold increase in the activity of recombinant muscle phosphorylase a with 0.2 mM AMP, which is consistent with published data on rabbit skeletal muscle phosphorylase a (Kasvinsky et al., 1978). The inhibitory effect of the T state promoter glucose on recombinant muscle phosphorylase a was counteracted by AMP. In summary, the kinetic properties of human recombinant skeletal muscle phosphorylase with respect to AMP are similar to those reported for rabbit skeletal muscle.

To test the hypothesis that differences in the effect of AMP and glucose on skeletal muscle and liver phosphorylase a activity would influence the selectivity of indole site inhibitors, the potencies of GPi688 and GPi819 were determined at a range of AMP and glucose concentrations. Glucose acted synergistically with the inhibitory effects of both inhibitors on liver phosphorylase a, as previously shown for the indole site inhibitor CP-91149 (Martin et al., 1998). Addition of AMP (0.2 mM) decreased the potency of both inhibitors to similar extents at all glucose concentrations. The reduction in inhibitor potency against liver phosphorylase a in the presence of a maximally activating concentration of AMP is consistent with the characterization of the indole site inhibitors as T state inhibitors (Oikonomakos et al., 2003).

To further study the effects of AMP on indole site inhibitors, we started with glucose concentrations where the potencies of each inhibitor were similar for both the liver and skeletal muscle phosphorylase a in the absence of AMP. For liver phosphorylase a, we chose 8 mM glucose, which is believed to be close to the intracellular hepatic concentration of glucose in the fasting state (Ercan et al., 1996; Künnecke et al., 2000). The glucose concentration required for the compounds to show similar potency against phosphorylated skeletal muscle was 15 mM. This suggests that the indole site inhibitors are intrinsically less effective at inhibiting the skeletal muscle enzyme, because at 15 mM glucose, in the absence of AMP, skeletal muscle phosphorylase a is only at ∼30% of glucose-free activity, whereas the liver enzyme with 8 mM glucose is at ∼65% glucose-free activity (Figure 2). To further support this conclusion, in assay conditions where the specific activities of the liver and skeletal muscle enzyme were approximately equal (8 mM glucose without AMP and 15 mM glucose with 0.2 mM AMP, respectively – see Figure 3), both inhibitors had greater potency against liver phosphorylase a.

The increase in inhibitor potency with decreasing AMP concentrations reflected the decrease in phosphorylase activity with decreasing AMP (Figures 3 and 5). Addition of the T state promoter caffeine, in the presence of 15 mM glucose, increased the potency of both indole site inhibitors against the skeletal muscle enzyme. These changes in potency accord with a shift of the enzyme activation state from R to T.

The effect of AMP on the indole site inhibitor potency contrasts with that of DAB. The binding site for DAB has not been fully identified, although kinetic analysis indicates DAB binds at or near the catalytic site (Fosgerau et al., 2000). The increase in DAB's potency in the presence of AMP is consistent with a site of action at or near the catalytic site. In the active state with AMP bound, access to the active site is ‘unblocked' (Buchbinder et al., 2001) and hence open to either substrate or inhibitor.

To determine if the in vitro difference in isoform potency observed with the indole site inhibitors is translated to a difference in in vivo efficacy, we investigated the effects of GPi819 treatment on glycogen content in liver and muscle tissues in Zucker (fa/fa) rats. We first established that there was no species difference in the potencies of GPi688 and GPi819 against recombinant rat and human liver phosphorylase a. Similar ED50 values for glucagon-stimulated glycogenolysis were also observed for both GPi688 and GPi819 in human and rat primary hepatocytes (unpublished data). This lack of species difference for liver phosphorylase is consistent with published data for the indole site inhibitor CP-91149 in rat and human liver cells (Martin et al., 1998). Comparison of the amino-acid sequence at the indole-binding site of rat and human liver phosphorylase shows only a single amino-acid substitution (Ala192 in rat, Ser192 in human) (Oikonomakos et al., 2002). Human and rat liver phosphorylase have 94% identity overall. Human and rat muscle phosphorylase have identical sequence at the indole-binding site and share 95% identity overall. Although potencies of GPi688 and GPi819 were not determined against rat recombinant muscle phosphorylase a, with the high degree of homology between rat and human muscle phosphorylase, we would expect our indole site inhibitors to show similar potency against muscle phosphorylase from both species. In our interpretation of the in vivo results we have assumed, this is the case.

In vivo, glycogen content was measured as the most proximal endpoint for glycogen phosphorylase activity. Five days dosing of GPi819 at 37.5 μmol kg−1 induced a greater fold increase in glycogen content in soleus muscle than in liver. As shown by measurement of compound concentration at the dose interval, tissue total compound levels were at steady state in muscle and liver. Although total compound levels in muscle and liver were 35- and fivefold higher than the corresponding values observed for plasma, steady-state free compound levels in each tissue were assumed to be in equilibrium with plasma-free compound levels (Rowland and Tozer, 1995). If this assumption is correct, our data suggest GPi819 has greater efficacy against glycogen content in muscle than in liver. If active transport of compound were occurring to increase exposure of free compound in muscle relative to liver, then this would alter the interpretation of our data. We have no evidence to suggest active transport is occurring with GPi819.

One alternative explanation of our data is that glycogen levels had reached the maximum storage capacity in the liver, but not in muscle. However, when GPi819 was administered at 125 μmol kg−1, we observed a further increase in glycogen levels in both tissues. This indicates that glycogen storage in liver and muscle was not saturated at 37.5 μmol kg−1, although it may be approaching maximal storage capacity at 125 μmol kg−1 (unpublished results).

The in vitro data show that the inhibitors are more potent at either low AMP or high glucose concentrations. Levels of AMP measured in skeletal muscle biopsies generally range from 20 to 100 μmol kg−1 wet weight (Newsholme and Leech, 1983; Arabadjis et al., 1993; Rush and Spriet, 2001; Baker et al., 2005; Hancock et al., 2005). In liver, physiological AMP levels determined by biochemical methods (Koch et al., 1998; Ercan-Fang et al., 2002) typically range from 680 to 1000 μmol kg−1 wet weight. Although the concentrations of free AMP in liver and muscle cannot be measured directly in vivo, they are thought to be significantly lower (Wheeler and Lowenstein, 1979; Iles et al., 1985; Hancock et al., 2006). A low AMP content in skeletal muscle is consistent with the view that AMP is rapidly deaminated to IMP, thus ensuring the reaction catalysed by adenylate kinase favours ATP production. Therefore, the efficacy of indole site inhibitors could be significantly greater in skeletal muscle than liver owing to a lower free AMP concentration.

In liver, glucose is considered the main allosteric regulator and the intracellular glucose concentration in fasting rats is almost equal to plasma glucose at ∼8 mM (Ercan-Fang et al., 2002). Glucose may not, however, be a physiologically important inhibitor in muscle. Studies using 13C NMR report intracellular glucose concentrations ranging from <0.1 to 0.3 mM in rat and human skeletal muscle (Cline et al., 1998, 1999). At these concentrations, glucose per se would have little inhibitory effect on skeletal muscle phosphorylase a (Figure 2).

The efficacy of the indole site inhibitor, GPi819 on muscle glycogen concentration in our Zucker (fa/fa) rat study is, therefore, consistent with either a low AMP in skeletal muscle or other T state promoters being the major physiological regulator in this tissue. The identification of the physiological T state promoter(s) in skeletal muscle is beyond the scope of this study.

We were unable to determine the potency of the indole site inhibitors, and the effect of glucose and AMP on inhibitor potency against the human recombinant skeletal muscle phosphorylase b, as our preparation of dephosphorylated enzyme lost activity rapidly with storage. Crystallographic studies with chloroindole compounds complexed with either rabbit skeletal muscle b form or human liver a form, show that the major interactions between inhibitor and protein are conserved (Oikonomakos et al., 2002). It has been proposed that indole site inhibitors will prevent the conversion of the b to a form (Baker et al., 2005). In vivo the relative amounts of a and b forms are regulated by phosphorylation and intracellular effector concentration. We cannot rule out the possibility that the greater efficacy of GPi819 in skeletal muscle is the result of differential potency against the b form in each tissue and/or a disparate contribution of the b form to total phosphorylase activity. Determination of the amount of a and b forms in the two tissues in the presence of a glycogen phosphorylase inhibitor would be required to address this issue.

In conclusion, differences in glucose and AMP regulation of liver and skeletal muscle phosphorylase a contribute to the diverging potency of indole site inhibitors against the two isoforms in vitro. In vivo, the indole site inhibitor GPi819 had a greater effect on glycogen content in skeletal muscle than liver in Zucker (fa/fa) rats. The lack of correlation between in vitro potency and in vivo efficacy could possibly be explained by tissue-specific differences in effector concentrations that may influence the efficacy of an indole site inhibitor in various tissues by altering the proportion of phosphorylase a in the R and T states. This will have implications for the overall safety and efficacy profile of these compounds.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Walter Ward, Dr Dave Smith, Dr Matthew Coghlan and Professor Loranne Agius for their helpful advice during the preparation of the paper, Dr Alan Birch and Dr Paul Whittamore and the AstraZeneca CVGI chemists, for the synthesis of GPi688 and GPi819, and Dr Dawood Dassu and Dr Jonathan Bright for valuable statistical advice. We gratefully acknowledge Julie Evans and Dr Mike Walker for tissue compound level measurements.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- DAB

1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol

- DMSO

dimethylsulphoxide

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDL

extensor digitorum longus

- LSD

least significant difference

- NAD+

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

- ODS

octadecyl silane

- PP1

protein phosphatase 1

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Arabadjis PG, Tullson PC, Terjung RL. Purine nucleoside formation in rat skeletal muscle fiber types. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1993;264:C1246–C1251. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.5.C1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AstraZeneca Heterocyclic amide derivatives as inhibitors of glycogen phosphorylase World Intellectual Property Organisation 2003. WO 03/074532 A1

- Baker DJ, Timmons JA, Greenhaff PL. Glycogen phosphorylase inhibition in type 2 diabetes therapy. A systematic evaluation of metabolic and functional effects in rat skeletal muscle. Diabetes. 2005;54:2453–2459. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder JL, Rath VL, Fletterick RJ. Structural relationships among regulated and unregulated phosphorylases. Annu Rev Biophy Biomol Struct. 2001;30:191–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline GW, Jucker BM, Trajanoski Z, Rennings AJM, Shulman GI. A novel 13C NMR method to assess intracellular glucose concentration in muscle, in vivo. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1998;274:E381–E389. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.2.E381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline GW, Petersen KF, Krssak M, Shen J, Hundal RS, Trajanoski Z, et al. Impaired glucose transport as a cause of decreased insulin-stimulated muscle glycogen synthesis in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:240–246. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan N, Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ. Allosteric regulation of liver phosphorylase a: revisited under approximated physiological conditions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1996;328:255–264. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan-Fang N, Gannon MC, Rath VL, Treadway JL, Taylor MR, Nuttall FQ. Integrated effects of multiple modulators on human liver glycogen phosphorylase a. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E29–E37. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00425.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosgerau K, Westergaard N, Quistorff B, Grunnet N, Kristiansen M, Lundgren K. Kinetic and functional characterization of 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol: a potent inhibitor of glycogen phosphorylase with anti-hyperglyceamic effect in ob/ob mice. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;380:274–284. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock CR, Janssen E, Terjung RL. Skeletal muscle contractile performance and ADP accumulation in adenylate kinase-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C1287–C1297. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00567.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock CR, Janssen E, Terjung RL. Contraction-mediated phosphorylation of AMPK is lower in skeletal muscle of adenylate kinase-deficient mice. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100:406–413. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00885.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iles RA, Stevens AN, Griffiths JR, Morris PG. Phosphorylation status of liver by 31P-N.M.R. spectroscopy, and its implications for metabolic control. Biochem J. 1985;229:141–151. doi: 10.1042/bj2290141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LN. Glycogen phosphorylase: control by phosphorylation and allosteric effectors. FASEB J. 1992;6:2274–2282. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.6.1544539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasvinsky PJ, Shechosky S, Fletterick RJ. Synergistic regulation of phosphorylase a by glucose and caffeine. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:9102–9106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M, Soman G, Graves DJ. A comparison of the activator sites of liver and muscle glycogen phosphorylase b. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:14041–14047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch JE, Ji H, Osbakken MD, Friedman MI. Temporal relationships between eating behavior and liver adenine nucleotides in rats treated with 2,5-AM. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1998;274:R610–R617. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.3.R610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künnecke B, Küstermann E, Seelig J. Simultaneous in vivo monitoring of hepatic glucose and glucose-6-phosphate by 13C-NMR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44:556–562. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200010)44:4<556::aid-mrm9>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerin C, Montell E, Nolasco T, Garcia-Rocha M, Guinovart JJ, Gomez-Foix A M. Regulation of glycogen metabolism in cultured human muscles by the glycogen phosphorylase inhibitor CP-91149. Biochem J. 2004;378:1073–1077. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Schulz DW, Passonneau JV. Effects of adenylic acid on the kinetics of muscle phosphorylase a. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:1947–1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Schulz DW, Passonneau JV. The kinetics of glycogen phosphorylases from brain and muscle. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:271–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs CM, Oikonomakos NG, Crowther RL, Hong L, Kammlott RU, Levin W, et al. The crystal structure of human muscle glycogen phosphorylase a with bound glucose and AMP: an intermediate conformation with T-state and R-state features. Proteins. 2006;63:1123–1126. doi: 10.1002/prot.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luong CBH, Browner MF, Fletteric RJ, Haymore BL. Purification of glycogen phosphorylase isozymes by metal-affinity chromatography. J Chromatogr Biomed Appl. 1992;584:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(92)80011-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddaiah VT, Madsen NB. Kinetics of purified liver phosphorylase. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3873–3881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WH, Hoover DJ, Armento SJ, Stock IA, McPherson RK, Danley DE, et al. Discovery of a human liver glycogen phosphorylase inhibitor that lowers blood glucose in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1776–1781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack JG, Westergaard N, Kristiansen M, Brand CL, Lau J. Pharmacological approaches to inhibit endogenous glucose production as a means of anti-diabetic therapy. Curr Pharm Des. 2001;7:1451–1474. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newgard CB, Hwang PK, Fletterick RJ. The family of glycogen phosphorylases: structure and function. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1989;24:69–99. doi: 10.3109/10409238909082552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme EA, Leech AR.Metabolism in exercise Biochemistry for the Medical Sciences 1983Wiley: Chichester; 357–381.(eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomakos NG, Acharya KR, Johnson LN.Rabbit muscle glycogen phosphorylase b. The structural basis of activation and catalysis Post-Translational Modifications of Proteins 1992CRC Press: Roca Raton; 81–151.In: Harding JJ, Crabbe MJC (eds.) [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomakos NG, Chrysina ED, Kosmopoulou MN, Leonidas DD. Crystal structure of rabbit muscle glycogen phophorylase a in complex with a potential hypoglycaemic drug at 2.0 angstrom resolution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1647:325–332. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(03)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomakos NG, Skamnaki VT, Tsitsanou KE, Gavalas NG, Johnson LN. A new allosteric site in glycogen phosphorylase b as a target for drug interactions. Structure. 2000;8:575–584. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomakos NG, Zographos SE, Skamnaki VT, Archontis G. The 1.76 angstrom resolution crystal structure of glycogen phosphorylase B complexed with glucose, and CP320626, a potential antidiabetic drug. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:1313–1319. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer Inc. Substituted N-(Indole-2-carbonyl-) amides and derivatives as glycogen phosphorylase inhibitors World Intellectual Property Organisation 1995. WO 96/39385 A1

- Rath VL, Ammirati M, Danley DE, Ekstrom JL, Gibbs EM, Hynes TR, et al. Human liver glycogen phosphorylase inhibitors bind at a new allosteric site. Chem Biol. 2000a;7:677–682. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath VL, Ammirati M, LeMotte PK, Fennell KF, Mansour MN, Danley DE, et al. Activation of human liver glycogen phosphorylase by alteration of the secondary structure and packing of the catalytic core. Mol Cell. 2000b;6:139–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland M, Tozer TN.Physiologic Concepts and Kinetics. Distribution Clinical Pharmacokinetics, Concepts and Applications 1995Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia; 137–155.In: Balado D (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Rush JWE, Spriet LL. Skeletal muscle glycogen phosphorylase a kinetics: effects of adenine nucleotides and caffeine. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:2071–2078. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.5.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang SR, Withers SG, Goldsmith EJ, Fletterick RJ, Madsen NB. Structural basis for the activation of glycogen phosphorylase b by adenosine monophosphate. Science. 1991;254:1367–1371. doi: 10.1126/science.1962195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalmans W, Gevers G. The catalytic activity of phosphorylase b in the liver. Biochem J. 1981;200:327–336. doi: 10.1042/bj2000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalmans W, Laloux M, Hers H-G. The interaction of liver phosphorylase a with glucose and AMP. Eur J Biochem. 1974;49:415–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan AWH, Nuttall FQ. Characteristics of the dephosphorylated form of phosphorylase purified from rat liver and measurement of its activity in crude liver preparations. Biochim et Biophys Acta. 1975;410:45–60. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(75)90206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler TJ, Lowenstein JM. Adenylate deaminase from rat muscle. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:8994–8999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]