Abstract

Background and purpose:

A crucial role for the GABAB receptor in depression was proposed several years ago, but there are limited data to support this proposition. Therefore we decided to investigate the antidepressant-like activity of the selective GABAB receptor antagonists CGP 36742 and CGP 51176, and a selective agonist CGP 44532 in models of depression in rats and mice.

Experimental approach:

Effects of CGP 36742 and CGP 51176 as well as the agonist CGP 44532 were assessed in the forced swim test in mice. Both antagonists were also investigated in an olfactory bulbectomy (OB) model of depression in rats, while CGP 51176 was also investigated in the chronic mild stress (CMS) rat model of depression. The density of GABAB receptors in the mouse hippocampus after chronic administration of CGP 51176 was also investigated.

Key results:

The GABAB receptor antagonists CGP 36742 and CGP 51176 exhibited antidepressant-like activity in the forced swim test in mice. The GABAB receptor agonist CGP 44532 was not effective in this test, however, it counteracted the antidepressant-like effects of CGP 51176. The antagonists CGP 36742 and CGP 51176 were effective in an OB model of depression in rats. CGP 51176 was also effective in the CMS rat model of depression. Administration of CGP 51176 increased the density of GABAB receptors in the mouse hippocampus.

Conclusions and Implications:

These data suggest that selective GABAB receptor antagonists may be useful in treatment of depression, and support an important role for GABA-ergic transmission in this disorder.

Keywords: GABAB receptors, CGP 36742, CGP 44532, CGP 51176, forced swim test, olfactory bulbectomy, chronic mild stress, depression

Introduction

Depression is a psychiatric disorder with high morbidity and mortality. The prevalence of depression has increased over the last 50 years (Healy 1998), affecting 10–15% of the population. It is also one of the most costly diseases; in the European Union, costs of affective disorders exceed 105 billion Euro (Andlin-Sobocki et al., 2005). Taking into account that only one case out of four is both diagnosed and properly treated and that ∼15% of patients with depression will commit suicide (Brody et al., 1998; Glass, 1999), the problem is difficult to overestimate. The serendipitous discovery of the antidepressant effects of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Loomer et al., 1957) and catecholamine uptake inhibitors (Kuhn, 1957) has formed the basis of the monoaminergic hypothesis of depression. Antidepressant therapy includes antidepressant drugs with a variety of pharmacological mechanisms, mostly affecting uptake or metabolism of monoamine neurotransmitters. However, antidepressants exert multiple adverse effects (Stahl, 2000) and have unsatisfactory efficacy. A role for the amino-acid neurotransmitter, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), in mood disorders was first proposed over 20 years ago by Emrich et al. (1980), based on the clinical observation that valproic acid, a GABA agonist, was effective in the treatment of bipolar patients. The studies of Lloyd and colleagues showing an upregulation of GABAB receptors after prolonged antidepressant treatment in rats (Pilc and Lloyd, 1984; Lloyd et al., 1985) focused attention on this receptor type.

GABA is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (Paredes and Agmo, 1992), acting via stimulation of GABAA, GABAB and GABAC receptors (Chebib and Johnston, 1999; Bormann, 2000; Rudolph et al., 2001). GABAA (and GABAC) receptors are coupled to chloride ion channels and mediate fast synaptic inhibition (Sieghart, 1992). GABAB receptors, discovered in 1980 (Bowery et al., 1980), were cloned in 1997 as the last group of receptors for this major neurotransmitter (Kaupmann et al., 1997). GABAB receptors are coupled through G proteins to neuronal potassium and calcium channels and mediate slow synaptic inhibition by increasing potassium and decreasing calcium conductance (Bowery, 1993). The GABAB receptor exists as a heterodimer formed by dimerization of two homologous subunits (GABAB1 and GABAB2) (Kaupmann et al., 1998; Marshall et al., 1999). The GABAB1 subunit binds the endogenous ligand, whereas GABAB2 subunit is responsible for the trafficking of the GABAB1 subunit to the cell surface and is responsible for interaction with G proteins (Thuault et al., 2004). On the subcellular level, most GABAB receptors are extrasynaptic, sometimes localized in close proximity to glutamatergic synapses (Fritschy et al., 1999; Lujan et al., 2004). Postsynaptic GABAB receptors activate inwardly rectifying potassium channels (Luscher et al., 1997). Activation of presynaptic GABAB receptors, acting as heteroreceptors or autoreceptors, causes an inhibition of neurotransmitter release (Bowery et al., 2002) by depressing Ca2+ influx via calcium channels.

3-Aminopropyl-n-butyl-phosphinic acid (CGP 36742) is one of the first GABAB receptor antagonists that can penetrate the blood–brain barrier after peripheral administration, with inhibition constant (IC50) of 32 μM (Bittiger et al., 1996). CGP 36742 was effective in the learned helplessness paradigm in rats, dose-dependently improving the escape failures induced by the inescapable shocks (Nakagawa et al., 1999), suggesting that it may have an antidepressant profile. CGP 51176 (3-amino-2(R)-hydroxypropyl-cyclohexylmethyl-phosphinic acid) is a GABAB receptor antagonist with IC50 of 6 μM (Froestl et al., 1995). Antidepressant-like effects were obtained with CGP 51176 in the chronic mild stress (CMS) model of depression and in the forced swim test in rats (Bittiger et al., 1996). Other selective GABAB receptor antagonists such as [3-[1-(S)-[[3-(cyclohexylmethyl)-hydroxyphosphinoyl]-2-(S)-hydroxy-propyl]amino]-ethyl]-benzoic acid, lithium salt (CGP 56433A) and (2S)-3-[[(1S)-1-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]amino-2-hydroxypropyl](phenylmethyl) phosphinic acid hydrochloride (CGP 55845A) were able to induce antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test in mice and in rats (Mombereau et al., 2004; Slattery et al., 2005), but not in the tail suspension test (Mombereau et al., 2004). Taken together, these data indicate that antagonists of the GABAB receptor may produce antidepressant effects in animals. The GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 36742 has recently been included in clinical trials for the treatment of mild cognitive impairments (Froestl et al., 2004).

In the present study, we examined the effects of acute treatment with two GABAB antagonists as well as with one agonist of the GABAB receptor in the forced swim test in mice. We also investigated the effects of acute and chronic treatment with these agents in rats using the olfactory bulbectomy (OB) model and the CMS model. Moreover, the effect of chronic treatment with CGP 51176 on GABAB receptor binding was also investigated with radiolabeled ligand binding assays. We now report that CGP 36742 and CGP 51176, GABAB receptor antagonists, exhibit antidepressant-like effects in rodent tests, and that the effect of CGP 51176 was antagonized by the GABAB receptor agonist (3-amino-2(S)-hydroxypropyl) methylphosphinic acid (CGP 44532).

Methods

Animals and housing

The experiments were performed on male Wistar rats (200–250 g) and male Albino Swiss mice (22–26 g). The animals were kept on a natural day–night cycle at room temperature of 19–21°C, with free access to food and water. Each experimental group consisted of 6–10 animals. All injections were given intraperitoneal (i.p.) in a volume of 2 or 10 ml kg−1in rats and mice, respectively. Experiments were carried out between 0900 and 1400 hours by an observer blind to the treatment. All experimental procedures were approved by Animal Care and Use Committee at the Institute of Pharmacology, Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków.

Forced swim test in mice

The test was carried out according to the method of Porsolt et al. (1977). Mice were chosen to perform the swim test in order to demonstrate the possible antidepressant-like effects of CGP 36742 in the second species. Thirty minutes after i.p. injection of tested compounds, mice were dropped individually into glass cylinders (height 25 cm, diameter 10 cm) filled with water to a height of 10 cm (maintained at 23–25°C), and left there for 6 min. After an initial 2-min period of vigorous activity, each animal assumes an immobile posture. The total duration of immobility within the last 4 min of the 6-min testing period was recorded. Mice were judged to be immobile when they remained floating passively in the water.

Locomotor activity in mice

Locomotor activity was measured using photoresistor actometers (circular cages, 25 cm in diameter, two light sources and two photoresistors). The animals were placed individually in an actometer for 6 min. The 6-min time was chosen to match the swimming time. Activity was also measured at 3-min intervals to characterize dynamics of changes. The number of light beams crossed by an animal was recorded as the locomotor activity. All drugs were injected 30 min before the test.

CMS model of depression

Male Wistar rats (our own breeding stock) were brought into the laboratory 2 months before the start of the experiment, at which time they weighed 200–250 g. They were first trained to consume a 1% sucrose solution; training consisted of eight 1 h baseline tests (twice weekly at 1000 hours) in which sucrose was presented, in the home cage, following 14 h food and water deprivation; the sucrose intake was measured by weighing pre-weighed bottles containing the sucrose solution, at the end of the test. Subsequently, sucrose consumption was monitored, under similar conditions, at weekly intervals throughout the entire experiment. On the basis of their sucrose intakes in the final baseline test, the animals were divided into two matched groups. One group of animals was subjected to the CMS procedure for a period of 7 consecutive weeks. Each week of stress regime consisted of: two periods of food or water deprivation, two periods of 45° cage tilt, two periods of intermittent illumination (lights on and off every 2 h), two periods of soiled cage (250 ml water in sawdust bedding), one period of paired housing, two periods of low intensity stroboscopic illumination (150 flashes/min) and three periods of no stress. All stressors were 10–14 h of duration and were applied individually and continuously, day and night. Control animals were housed in separate rooms and had no contact with the stressed animals. They were deprived of food and water for the 14 h preceding each sucrose test, but otherwise food and water were freely available in the home cage. On the basis of their sucrose intake scores following initial 3 weeks of stress, both stressed and control animals were each divided further into five matched subgroups (n=8), and for the subsequent 6 weeks they received saline (1 ml kg−1), CGP 51176 (0.3, 3.0 and 30 mg kg−1) or imipramine (10 mg kg−1) as the reference treatment. These drugs were administered twice daily at 1000 and 1700 hours. Sucrose tests were carried out 24 h following the last drug treatment (the second administration preceding the sucrose test was omitted). After 5 weeks, all treatments were terminated and one additional sucrose test was carried out following 1 week of withdrawal. Stress was continued throughout the period of treatment and withdrawal. The CMS model is a long (4 months) and very time-consuming procedure. The treatment groups (n=8 rats/group) included control and stressed animals given vehicle, the reference drug (imipramine) and three doses of the CGP compound. This means that each drug administration takes approximately 2 h (4 h in case of twice daily dosing). The injections have to be done before the changes of the light/dark cycle, they cannot interfere with the application of the stressors and the timing schedule has to take into account results of the pharmacokinetic analysis. The time gap of 7 h (i.e. injections at 1000 and 1700 hours) appears to follow all the above requirements.

OB – surgical procedure

After 2 weeks' acclimation period, bilateral OB was performed in rats anesthetized with Vetbutal (BioWet, Puławy, Poland) given in dose of 10 mg kg−1 i.p. Following exposure of the skull, 2 mm diameter holes were drilled at the points 7 mm anterior to the bregma and 2 mm either side of the midline. The olfactory bulbs were removed by suction and holes were filled with hemostatic sponge to stop the bleeding and the skin was closed. Sham-operated animals were treated in the same way but the bulbs were left intact. After the surgery, rats were kept four per cage (two sham+two bulbectomized). The animals were given 14 days to recover following surgery before drug administration and during this period they were handled daily by the experimenter to eliminate any aggressiveness that would otherwise arise. Two weeks after surgery, drug treatment began. CGP 36742 (10 mg kg−1) or CGP 51176 (3 mg kg−1) were administered chronically once daily for 14 days or acutely at doses of 10 mg kg−1 i.p. The doses of both antagonists were chosen on the basis of the results of CMS or swim test studies. Control animals received a vehicle solution (0.9% sodium chloride).

Open field test in OB rats

Forty-five minutes after the last dose of CGP 36742 or CGP 51176, the open field test was performed. Each rat was placed individually into the center of the ‘open field' apparatus. The ‘open field' apparatus was a circle made of wood, 90 cm in diameter. The test was performed between 0900 and 1200 hours. The number of rearings and peepings was measured during a 3-min observation period. Experiments were performed in a darkened room and the apparatus was illuminated by a 60 W bulb positioned 1 m above the center of the circle.

Passive avoidance test in OB rats

Twenty-four hours after the open field test, rats were injected once more with antagonists or saline. Forty-five minutes after the last dose of CGP 36742 or CGP 51176, the passive avoidance test was performed. In experiments with administration of a single dose of CGP 36742, rats were treated for 14 days with saline, followed by a single injection of CGP 36742, 45 min latter the passive avoidance test was performed. The passive avoidance apparatus consisted of a Plexiglas box (50 × 50 × 50 cm) with a grid floor. The grid floor consisted of parallel steel rods set 1.2 cm apart. A wooden platform (12 × 12 × 4 cm) was placed in the center of the grid floor. Rats were placed individually on a wooden platform and when the rat stepped down from the platform and placed all its paws on the grid floor, an intermittent electroshock (0.75 mA) was delivered for 1 s. The animals were immediately removed from the experimental cage and transferred to the home cage. After 30 s, the next trial on the same rats was initiated. The training of the rats was stopped if the rats learned not to leave the platform before the passage of 1 min or if 15 trials were given.

Radioligand binding assay

Male Albino Swiss mice were treated once a day with CGP 51176 (1 mg kg−1) or saline, for 28 days. Twenty-four hours after the last treatment, animals were killed, brains removed and hippocampi dissected and frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. [3H]CGP-54626 (cyclohexylmethyl-{(S)-3-[(S)-1-(3,4-dichloro-phenyl)-ethylamino]-2-hydroxy-propyl}-phosphinic acid hydrochloride) was used as the radioligand. The membrane preparation and the assay procedure were carried out according to the published procedure (Bittiger et al., 1992) with slight modifications.

Hippocampi were homogenized using Ultra Turrax in 10 ml of ice-cold 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4). The tissue suspension was centrifuged at 15 000 g for 20 min (0–4°C). The pellet was resuspended in the same volume of Tris buffer by homogenization and centrifuged again at 15 000 g for 20 min (0–4°C). This pellet was twice more resuspended and homogenized in the same volume of buffer and centrifuged for 25 min at the same settings. The pellet was then frozen at −20°C at least for 18 h. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in Tris-HCl buffer in a proportion of 1 g tissue to 35 ml buffer. The final incubation mixture (final volume 300 μl) consisted of 240 μl of membrane suspension, 30 μl of a [3H]CGP 54626 solution (containing six concentrations of the ligand ranging from 0.125 to 20 nM; 200 000 c.p.m. at the highest concentration) and 30 μl of Tris-HCl buffer. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of GABA (10−4 M). Samples were incubated for 10 min on ice. The incubation was terminated by rapid filtration over glass fiber filters (Whatman GF/C). The filters were washed two times with 5 mM ice-cold buffer and immersed in 4 ml of a scintillation liquid. Radioactivity was measured in a WALLAC 1409 DAS – liquid scintillation counter. All assays were done in duplicates. Protein concentrations were determined using BCA protein assay kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA).

Data were analyzed using iterative curve fitting routines (GraphPAD/Prism, Version 3.0 – San Diego, CA, USA).

Drugs

CGP 36742, CGP 51176 and CGP 44532 were obtained from Dr Wolfgang Froestl (Novartis, Switzerland). [3H]CGP-54626, [S-(R* R*]-[[1-(3,4-dichloropheny-l0-ethyl]amino]-2-hydroxypropyl]([3,4–3H]-cyclohexylmethyl)phosphinic acid (specific activity 1850 GBq/mmol) was purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK). Imipramine HCl was purchased from RBI (Natick, MA, USA).

Data analysis

The data were evaluated by one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison test or Newman–Keuls test or Student's t-test, P<0.05 was considered significant. Data obtained in the CMS experiment (sucrose intakes) were analyzed by multiple ANOVA with three between-subjects factors (stress/control, drug treatments and successive sucrose tests), followed by the post hoc comparisons of means (Fisher's least significant difference test).

Results

Forced swim test in mice

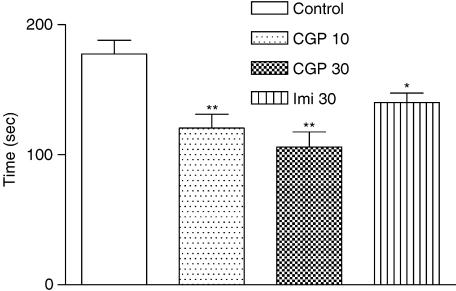

CGP 36742 at 10 and 30 mg kg−1, significantly reduced the immobility time in the forced swim test at both doses (10 mg kg−1 by 32% and 30 mg kg−1 by 40%), (Figure 1), whereas the reference compound, imipramine, administrated at a dose of 30 mg kg−1, significantly decreased the immobility time by 21%. At doses greater than 8 mg kg−1, the other GABAB receptor antagonist, CGP 51176, significantly reduced the immobility time in the forced swim test by 31% (Table 1a and b). The GABAB receptor agonist, CGP 44532 (0.125 or 0.25 mg kg−1), was not effective in the forced swim test (Table 1c); however, at a dose of 0.125 mg kg−1, it significantly blocked the antidepressant-like activity of CGP 51176 at a dose of 8 mg kg−1 (Table 1d). Control (vehicle-treated) mice exhibit variability in the immobility time. That may be due to using independent groups of animals and experiments performed several weeks apart, therefore separate controls for each group of animals are presented.

Figure 1.

Effect of CGP 36742 (10 or 30 mg kg−1) on the total duration of immobility in the forced swim test in mice. CGP 36742 and imipramine (30 mg kg−1) were administrated at 30 min before the test. Values are expressed as means±s.e.m. of eight mice per group. ANOVA as follows: F=9.188 (3,28), P<0.0001,*P<0.05, **P<0.01, vs vehicle-treated control group.

Table 1.

Effect of treatment with CGP 51176, CGP 44532 and their co-treatment on the total duration of immobility in the forced swim test in mice

| Compound | Dose (mg kg−1) | Immobility time (s) |

|---|---|---|

| a | ||

| Vehicle | — | 170.7±10.4 |

| CGP 51176 | 5 | 145.9±11.7 |

| CGP 51176 | 8 | 117.8±7.7* |

| IMI | 30 | 93.7±11.5* |

| B | ||

| Vehicle | — | 205.0±3.3 |

| CGP 51176 | 10 | 174.3±8.4* |

| CGP 51176 | 12 | 172.0±8.6* |

| c | ||

| Vehicle | — | 206.2±12.5 |

| CGP 44532 | 0.125 | 183.3±17.1 |

| CGP 44532 | 0.250 | 225.5±6.5 |

| d | ||

| Vehicle | — | 154.0±12.3 |

| CGP 51176+ | 8 | 180.2±9.6 |

| CGP 44532 | 0.125 | |

Abbreviations: CGP 44532, (3-amino-2(S)-hydroxypropyl) methylphosphinic acid; CGP 51176, 3-amino-2(R)-hydroxypropyl-cyclohexylmethyl-phosphinic acid; IMI, imipramine.

CGP 51176, CGP 44532 and IMI were given 30 min before the test. Values are expressed as means±s.e.m. of 6–7 mice per group.

ANOVA: A – F(3,23)=10.144, P=0.0002; B – F(2,17)=5.6, P<0.02; C – F(2,17)=3.28, P>0.05. Students' t-test: D – t(11)=1.709, P=0.1166, NS.

P<0.01 vs vehicle.

Locomotor activity in mice

CGP 36742 at doses of 10 or 30 mg kg−1 had no effect on the spontaneous locomotor activity in mice (Table 2). Neither the GABAB receptor antagonist, CGP 51176 (8–12 mg kg−1) nor the GABAB receptor agonist CGP 44532 (0.125–0.25 mg kg−1), influenced the locomotor activity of mice (Table 3a and b). Combined treatment with CGP 51176 (8 mg kg−1) and CGP 44532 (0.125 mg kg−1), still had no effect on the locomotor activity (Table 3c).

Table 2.

Effect of CGP 36742 on spontaneous locomotor activity in mice

| Compound | Dose (mg kg−1) |

Activity counts |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 min | 6 min | ||

| Vehicle | — | 57.6±14.0 | 99.9±19.8 |

| CGP 36742 | 10 | 62.5±13.2 | 121.6±24.3 |

| 30 | 64.3±14.2 | 119.8±30.1 | |

Abbreviation: CGP 36742, 3-aminopropyl-n-butyl-phosphinic acid.

CGP 36742 (10 or 30 mg kg−1) was given 30 min before the test. Values are expressed as means±s.e.m of eight mice per group. ANOVA as follows F(2,20)=0.48 P<0.6028, NS, 3 min; F(2,20)=1.66 P<0.215, NS, 6 min.

Table 3.

Effect of treatment with CGP 51176, CGP 44532 and their co-treatment on spontaneous locomotor activity in mice

| Compound | Dose (mg kg−1) |

Activity counts |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 min | 6 min | ||

| a | |||

| Vehicle | — | 62.9±6.5 | 109.1±9.6 |

| CGP 51176 | 8 | 67.0±4.2 | 119.0±10.4 |

| b | |||

| Vehicle | — | 100.8±9.6 | 176.5±12.8 |

| CGP 51176 | 10 | 84.0±9.2 | 167.8±12.3 |

| CGP 51176 | 12 | 84.9±14.1 | 145.1±20.4 |

| CGP 44532 | 0.125 | 100.3±8.9 | 165.3±16.2 |

| CGP 44532 | 0.250 | 75.6±5.2 | 145.6±14.5 |

| c | |||

| Vehicle | — | 69.7±4.4 | 118.9±9.5 |

| CGP 51176+ | 8 | 70.8±2.9 | 120.8±5.9 |

| CGP 44532 | 0.125 | ||

Abbreviations: CGP 44532, (3-amino-2(S)-hydroxypropyl) methylphosphinic acid; CGP 51176, 3-amino-2(R)-hydroxypropyl-cyclohexylmethyl-phosphinic acid.

CGP 51176 or CGP 44532 were administered at 30 min before test. Values are expressed as means±s.e.m. of 6–8 mice per group. Students' t-test: A: t(13)=0.5124, P=0.6169 for 3 min; t(13)=0.7001, P=0.4962 for 6 min; C: t(13)=0.2021, P=0.8429 for 3 min; t(13)=0.1640, P=0.8723 for 6 min. ANOVA: F(4,36)=1.252, P=0.3090 for 3 min; F(4,36)=0.8500, P=0.5042 for 6 min.

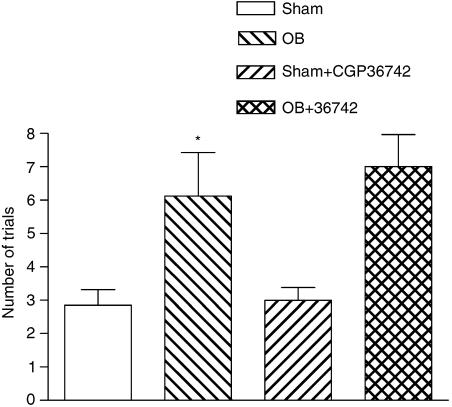

Passive avoidance test in OB rats

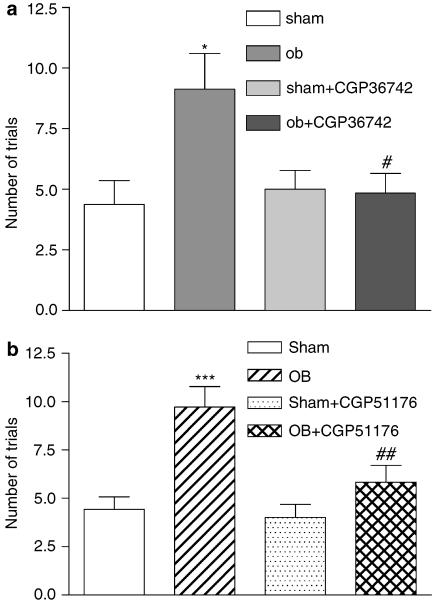

Single administration of CGP 36742 did not alter the OB-induced learning deficit (Figure 2), induced following bulbectomy. The effect of chronic CGP 36742 treatment (at 10 mg kg−1) on passive avoidance acquisition is shown in Figure 3a. Sham-operated rats learned the passive avoidance situation in approximately four trials, whereas bulbectomized rats needed an average of nine trials to reach the same criterion. Chronic administration of CGP 36742 restored the learning deficit in OB rats (five trials) without affecting performance in sham-operated animals. The effect of chronic CGP 51176 treatment (at 3 mg kg−1) on passive avoidance acquisition is shown in Figure 3b. Bulbectomized animals needed twice as many trials to learn the passive avoidance situation, comparing to control rats. Chronic administration of CGP 51176 (3 mg kg−1) restored the learning deficit in OB rats (five trials) without affecting performance in sham-operated animals (Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

Effect of single administration of CGP 36742 on passive avoidance acquisition in OB model in rats. These tests were performed 45 min after the last drug administration. Values are expressed as means±s.e.m. of 7–8 mice per group. ANOVA as follows: F(1,26)=0.31, P=0.58, OB vs OB+CGP 36742-treated rats; F(1.26)=15.85, P<0.001, Sham vs OB rats, *P<0.001.

Figure 3.

Effect of chronic treatment with CGP 36742 (a) or CGP 51176 (b) on passive avoidance acquisition in OB model in rats. These tests were performed 45 min after the last administration of chronic treatment. Each column represents the mean±s.e.m. of 7–8 animals per group. ANOVA as follows: (a) F (1.26)=4.47, P<0.05, sham vs OB rats; F (1,26)+18.29, P<0.001 OB vs OB+CGP 36742-treated rats, *P<0.05, #P<0.001. Moreover, there was a significant interaction between the groups (F (1,26)=19,97, P=0.04). (b) F (1,22)=17.66, P<0.001, sham vs OB rats; F (1,22)=6.472, P<0.04, OB vs OB+CGP 51176-treated rats; ***P<0.001, ##P<0.05.

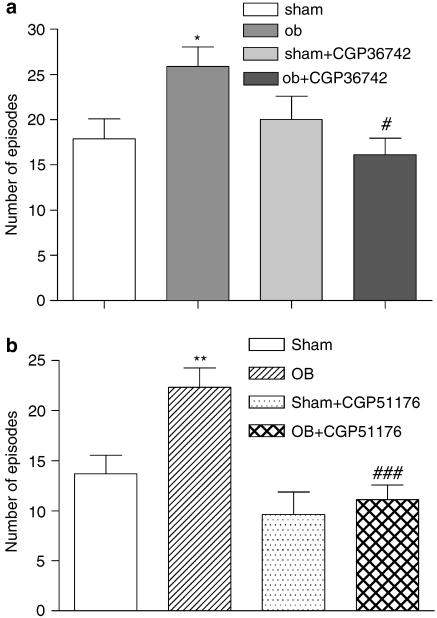

Open field test in OB rats

In the open field test, the OB procedure caused a significant increase (about 50%) in the number of rearings+peepings compared to sham-operated animals (Figure 4a). Repeated administration of CGP 36742 (at 10 mg kg−1) reduced this OB-related increase in the number of rearings+peepings. Chronic administration of CGP 51176 (3 mg kg−1) also significantly reduced the OB-related increase in the number of rearings+peepings (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Effect of chronic treatment with CGP 36742 (a) or CGP 51176 (b) on the number of rearings+peepings in open field test in OB model in rats. These tests were performed 45 min after the last administration of chronic treatment. Each column represents the mean±s.e.m. of 7–8 animals per group. ANOVA as follows: (a) F (1.26)=9,332, P=0.005, sham vs OB rats; F (1,26)=4.569, P<0.04, OB vs OB+CGP 36742-treated rats. There was a significant interaction between the groups (F(1,26)=10,7, P=0.003). *P<0.001, #P<0.05. (b) F (1,26)=4.99, P=0.004, sham vs OB rats; F (1,26)=9.38, P=0.004, OB vs OB+ CGP 51176-treated rats. There was a significant interaction between the groups (F (1,26)=20.28, P=0.032). **P<0.01, ###P<0.001.

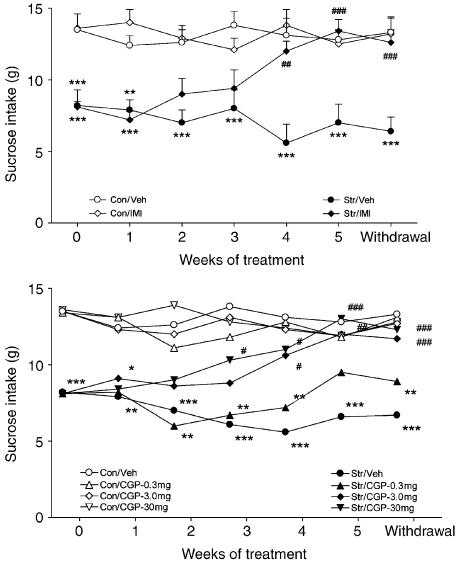

Chronic mild stress

The CMS procedure caused a gradual decrease in the consumption of 1% sucrose solution. In the final baseline test, sucrose intake was approximately 13 g in both groups. Following 3 weeks of stress, intake remained at a similar level in control animals, but fell to approximately 8 g in stressed animals. Such a difference between control and stressed animals treated with vehicle, persisted at the same level for the remainder of the experiment. As shown in Figure 5, imipramine or CGP 51176 had no significant effects in control animals. However, the two drugs caused a gradual increase of sucrose intake in stressed animals, resulting in a significant treatment effect, developing over the weeks of treatment. Sucrose intake in imipramine-treated animals was increased significantly from week 0 after 4 weeks of treatment (P<0.01), and this increase was maintained thereafter. After 5 weeks of treatment, there were no differences between drug-treated stressed animals and drug- and saline-treated controls (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of chronic treatment with saline (Con) (1 ml kg−1), imipramine (IMI) (10 mg kg−1) and CGP 51176 (CGP) (0.3, 3.0 and 30 mg kg−1) on the consumption of 1% sucrose solution in controls (open symbols) and in animals exposed to CMS (closed symbols). Treatment commenced following 2 weeks of stress. Values are means±s.e.m. (in the lower panel, s.e.m. were omitted for clarity). ANOVA as follows: (Group effect F (1,989)=254,2, P<0.001), control vs stressed animals; [IMI: F (1,98)=0.44, NS], control vs control/IMI-treated rats; (CGP: F (3,196)=1.39, NS), control vs control/CGP-treated rats; (IMI: F (1,98)=112,36, P<0.001), stressed vs stressed /IMI-treated rats; (CGP; F (1,196)=36.94, P<0.001), stressed vs stressed/CGP-treated rats; treatment × weeks interaction, (IMI: F(6,98)=13.08, P<0.001; CGP: F(18,19)60+ 2.99, P<0.01] *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs saline or drug-treated control groups; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs drug-treated stressed animals at Week 0.

As shown in Figure 5b, CGP 51176 reversed the CMS-induced anhedonia in a dose-dependent manner. Sucrose intakes in animals treated with 3.0 or 30 mg kg−1 were increased significantly from week 0 (P<0.05) after 3 and 4 weeks of treatment, respectively, and after 5 weeks of treatment, there were no significant differences between drug-treated stressed animals and drug- and saline-treated controls. CGP 51176 administered at the dose of 0.3 mg kg−1 had no significant effect on the sucrose consumption in either control or stressed animals. The increase in sucrose intake in stressed animals treated with imipramine and CGP 51176 (3.0 and 30 mg kg−1) was maintained 1 week after cessation of treatment (see Figure 5).

GABAB receptor binding

Chronic (4 weeks) treatment with GABAB receptor antagonist CGP 51176 (1 mg kg−1) induced a significant 98% increase in the density of GABAB receptor antagonist [3H]CGP 54626A binding to GABAB receptors in the mouse hippocampus without alterations in the affinity (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of chronic (4 weeks) CGP 51176 treatment on the binding of [3H]CGP 54626A to GABAB receptors in mouse hippocampus

| Treatment | Bmax (fmol mg protein−1) | KD (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 744.2±83.5 | 1.52±0.17 |

| CGP 51176 | 1474.5±274.4* | 2.22±0.27 |

Abbreviations: CGP 51176, 3-amino-2(R)-hydroxypropyl-cyclohexylmethyl-phosphinic acid; CGP 54626, cyclohexylmethyl-(S)-3-[(S)-1-(3,4-dichloro-phenyl)-ethylamino]-2-hydroxy-propyl-phosphinic acid hydrochloride.

Mice were treated with CGP 51176 or vehicle for 4 weeks. Twenty-four hours after the last treatment, animals were killed, hippocampi were dissected and binding of [3H]CGP 54626A to GABAB receptors was assessed. Results are expressed as means±s.e.m. of five mice per group. Students' t-test: t(8)=2.546, P=0.0344 for Bmax; t(8)=2.194, P=0.0595, NS for KD.

P<0.05 vs vehicle group.

Discussion

The present study was conducted on both rats and mice because we wanted to confirm that the antidepressant-like activity produced by the tested compounds is a generalized phenomenon and not a phenomenon specific to rats or mice. Moreover, our findings showing that similar effects can be observed in one laboratory in both species provide further support for results of the studies conducted either on rats or mice in different laboratories.

In the present study, we demonstrated that the selective GABAB receptor antagonists, CGP 36742 and CGP 51176 were active in the forced swim test, which is an important assay to predict antidepressant-like properties of drugs (Porsolt et al., 1977, 1978). These results conformed to and extended previous studies (Bittiger et al., 1996; Nakagawa et al., 1999). Other selective antagonists of GABAB receptors such as CGP 56433A and CGP 55845A were also able to induce antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test in mice or rats (Mombereau et al., 2004; Slattery et al., 2005), but not in the tail suspension test (Mombereau et al., 2004), supporting the view that GABAB receptor antagonism may serve as a basis for the generation of novel antidepressants (Mombereau et al., 2004). The fact that the GABAB receptor agonist CGP 44532 was not able to produce antidepressant-like effect in the forced swim test in mice but counteracted the activity of an antagonist CGP 51171 supports that line of thinking and extends the findings of Nakagawa et al. (1999) who have shown that baclofen, the prototype GABAB receptor agonist, blocked the antidepressant effect of CGP 36742, as well as the action of the classical antidepressant imipramine in rats (Nakagawa et al., 1996).

Surgical lesion of the OB in animals induces significant behavioral, physiological, endocrine and immune changes, many of which were qualitatively similar to those observed in depressive patients (for review, see Kelly et al., 1997). In animal studies, a variety of OB-related behavioral changes, including hyperactivity in the ‘open field' and deficiency in passive avoidance, responded selectively to antidepressant treatment. The passive avoidance deficit is susceptible to acute administration of antidepressants, whereas hyperactivity in the ‘open field' always responds to chronic treatment with antidepressants, mimicking the clinical lag-time of currently used antidepressant drugs (Harkin et al., 2003). We used both tests to evaluate a potential antidepressant-like effect of GABAB receptor antagonists in the OB model of depression. As it was the requirement of the ethics committee to reduce the number of animals subjected to bulbectomy, appropriate doses were inferred from the data of the CMS and forced swim test experiments and we decided to use a single dose of antagonists in this model of depression. Repeated but not single administration of CGP 36742 and repeated administration of CGP 51176 attenuated the hyperactivity of OB rats in this test and attenuated the learning deficit in the passive avoidance experiment. We also found that repeated administration of GABAB antagonists did not result in any behavioral changes in the sham-operated groups, indicating that the effect of CGP 36742 and CGP 51176 in OB rats was not due to a stimulant or sedative effect of these compounds. The OB model of depression has been previously used to assess a series of novel potential antidepressant drugs, including those acting via the glutamatergic system, such as the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist dizocilpine (Redmond et al., 1997) or mGlu5 receptor antagonists such as MTEP or MPEP (Pilc et al., 2002; Pałucha et al., 2005). The OB model appears to be also useful to investigate the antidepressant-like effects of GABAB antagonists. The lack of effects of CGP 51176 on the locomotor activity in mice supports the data of Colombo et al. (2001) who did not find any effects of GABAB receptor antagonists on locomotor activity of mice at 5 or 10 min after drug administration, the times used in our experiments. An increase in locomotor activity in his experiments was observed 20 min after drug administration.

Chronic sequential exposure to a variety of mild stressors (CMS) causes a substantial decrease in the consumption of 1% sucrose solution, a deficit that can be effectively reversed by chronic treatment with traditional antidepressant drugs (Papp et al., 1996). Moreover, as in most of the previous studies with the CMS model (Willner, 1997, 2005), we observed that the action of imipramine had several parallels with its clinical activity, in terms of its efficacy (full recovery at the end treatment period), specificity (as indicated by a lack of significant effects in control animals) and time course (4–5 weeks of treatment required to reverse the deficit in sucrose consumption). CMS induces behavioral alteration in rats (reduction of an intake of a sweet solution), which, with some reservations, models anhedonia in humans (Willner, 1997, 2005). Anhedonia is a core symptom of human depression and, therefore, CMS is an established animal model. An important finding of the present study is that the CMS-induced reduction in the intake of sucrose solution can be normalized by chronic administration of CGP 51176, confirming the data of Bittiger et al. (1996), which, however, are available only in the abstract form.

Recent behavioral studies results indicated that antagonists, but not agonists, of GABAB receptors exert antidepressant-like effects in the preclinical studies using both mice and rats (for review see Cryan and Kaupmann, 2005). This notion is further supported by the data using knockout mice. It has been shown that GABAB(1) −/− mice had decreased immobility (antidepressant-like behavior) in the forced swim test (Mombereau et al., 2004) and mice lacking GABAB(2) receptor subunit also have been shown to have antidepressant-like behavior (Mombereau et al., 2005), supporting the view that it is GABAB receptor antagonism that is responsible for antidepressant-like effects. The increase in the GABAB receptor binding which was observed in several studies after treatment with GABAB receptor antagonist such as CGP 36742 or SCH 50,911 (Malcangio et al., 1993; Pratt and Bowery, 1993; Pibiri et al., 2005) in rats and mice, was confirmed in our experiments using CGP 51176 and is consistent with the view that the prolonged blockade of the GABAB receptor leads to its upregulation.

Data are accumulating that support the idea that, in depression, a hypofunction of the GABA-ergic system takes place (for review see Pilc and Nowak, 2005). Using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy, lowered GABA levels were detected in depressed patients (Sanacora et al., 1999, 2004), which were normalized after administration of electroconvulsive treatment (Sanacora et al., 2002) or antidepressant drugs (Sanacora et al., 2002; Bhagwagar et al., 2004). Therefore, if depression is due to hypoactivity of GABA-ergic transmission in the brain, one might expect that agonists of GABAB receptors should produce antidepressant effects. Such reports indeed were published, showing that GABA-receptor agonists, progabide and fengabine produce antidepressant effects in animal and in human studies (Lloyd et al., 1983, 1987). Both substances, however, are nonselective agonists of the GABA-receptors and cannot be regarded as selective GABAB receptor agonists. An increase in the GABAB receptor density and/or function shown here after GABAB receptor antagonist treatment can be envisaged as a compensatory mechanism to the prolonged receptor blockade. This increase paradoxically can lead to an increase in the inhibitory neurotransmission in the brain, exerted by stimulation of the GABAB receptor system (see Introduction). An increase in the GABAB receptor binding and/or function shown in the majority of studies after antidepressant drugs (see Enna and Bowery, 2004; Sands et al., 2004) can also be considered as a means to increase the inhibitory transmission in the brain, which remains in line with the concept that antidepressant drugs enhance GABA-ergic neurotransmission (Lloyd et al., 1985).

To summarize, our data support the view that GABAB receptor antagonists possess antidepressant potential. The recent advances in our understanding of GABAB receptor function, as well as the discovery of new selective GABAB receptor ligands may give us new tools both to understand the etio-pathogenesis of depression and to treat the disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Polpharma Foundation for Pharmacy and Medicine Grant No.: 34/4/2006 to A Pilc.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CGP 36742

3-aminopropyl-n-butyl-phosphinic acid

- CGP 44532

(3-amino-2(S)-hydroxypropyl) methylphosphinic acid

- CGP 51176

3-amino-2(R)-hydroxypropyl-cyclohexylmethyl-phosphinic acid

- CGP-54626

cyclohexylmethyl-{(S)-3-[(S)-1-(3,4-dichloro-phenyl)-ethylamino]-2-hydroxy-propyl}-phosphinic acid hydrochloride

- CGP 55845A

(2S)-3-[[(1S)-1-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]amino-2-hydroxypropyl] (phenylmethyl) phosphinic acid hydrochloride

- CGP 56433A

[3-[1- (S)-[[3-(cyclohexylmethyl)-hydroxyphosphinoyl]-2-(S)-hydroxy-propyl]amino]-ethyl]-benzoic acid, lithium salt

- CMS

chronic mild stress

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- OB

olfactory bulbectomy

Conflict of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- Andlin-Sobocki P, Jonsson B, Wittchen H, Olesen J. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12 (Suppl 1):1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwagar Z, Wylezińska M, Taylor M, Jezzard P, Matthews PM, Cowen PJ. Increased brain GABA concentrations following acute administration of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:368–370. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittiger H, Froestl W, Gentsch C, Jaekel J, Mickel SJ, Mondadori C, et al. GABAB receptor antagonists: potential therapeutic applications GABA: Receptors, Transporters and Metabolism 1996Birkhauser: Basel; 297–305.In: Tanaka C, Bowery NG (eds) [Google Scholar]

- Bittiger H, Reymann N, Froestl W, Mickel SJ. 3H-CGP: a potent radioligand for GABAB receptors. Pharmacol Commun. 1992;2:23. [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J. The ‘ABC' of GABA receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:16–19. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery NG. GABAB receptor pharmacology. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;33:109–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery NG, Bettler B, Froestl W, Gallaghe JP, Marshall F, Raiter M, et al. International Union of Pharmacology. XXXIII. Mammalian gamma-aminobutyric acid(B) receptors: structure and function. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:247–264. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowery NG, Hill DR, Hudson AL, Doble A, Middlemiss DN, Shaw J, et al. Baclofen decreases neurotransmitter release in the mammalian CNS by an action at a novel GABA receptor. Nature. 1980;283:92–94. doi: 10.1038/283092a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody DS, Hahn SR, Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, Degruy FV, et al. Identifying patients with depression in the primary care setting: a more efficient method. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.22.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo G, Melis S, Brunetti G, Serra S, Vacca G, Carai MA, et al. GABA(B) receptor inhibition causes locomotor stimulation in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;433:101–104. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01494-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chebib M, Johnston GA. The ‘ABC' of GABA receptors: a brief review. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999;26:937–940. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Kaupmann K. Don't worry ‘B' happy!: a role for GABA(B) receptors in anxiety and depression. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emrich HM, Von Zerssen D, Kissling W, Moller HJ, Windorfer A. Effect of sodium valproate on mania. The GABA-hypothesis of affective disorders. Arch Psychiat Nervenk. 1980;229:1–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00343800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enna SJ, Bowery NG. GABA(B) receptor alterations as indicators of physiological and pharmacological function. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1541–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Meskenaite V, Weinmann O, Honer M, Benke D, Mohler H. GABAB-receptor splice variants GB1a and GB1b in rat brain: developmental regulation, cellular distribution and extrasynaptic localization. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:761–768. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froestl W, Gallaghe M, Jenkins H, Madrid A, Melche T, Teichman S, et al. SGS742: the first GABA(B) receptor antagonist in clinical trials. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1479–1487. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froestl W, Mickel S, Von Sprecher G, Diel PJ, Hall RG, Maie L, et al. Phosphinic acid analogues of GABA. 2. Selective, orally active GABAB antagonists. J Med Chem. 1995;38:3313–3331. doi: 10.1021/jm00017a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass RM. Treating depression as a recurrent or chronic disease [editorial; comment] JAMA. 1999;281:83–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkin A, Kelly JP, Leonard BE. A review of the relevance and validity of olfactory bulbectomy as a model of depression. Clin Neurosci Res. 2003;3:253–262. [Google Scholar]

- Healy D. Antidepressant therapy at the dawn of the third millennium. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173:92. [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Huggel K, Heid J, Flor PJ, Bischoff S, Mickel SJ, et al. Expression cloning of GABA(B) receptors uncovers similarity to metabotropic glutamate receptors [see comments] Nature. 1997;386:239–246. doi: 10.1038/386239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaupmann K, Malitschek B, Schuler V, Heid J, Froestl W, Beck P, et al. GABA(B)-receptor subtypes assemble into functional heteromeric complexes. Nature. 1998;396:683–687. doi: 10.1038/25360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P, Wrynn AS, Leonard BE. The olfactory bulbectomized rat as a model of depression: an update. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;74:299–316. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(97)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R. Uber die Behandlung depressiver Zustande mit einem Imidibenzylderivat. Schwei Me Wochensch. 1957;35/36:1135–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd KG, Morselli PL, Depoortere H, Fournier V, Zivkovic B, Scatton B, et al. The potential use of GABA agonists in psychiatric disorders: evidence from studies with progabide in animal models and clinical trials. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;18:957–966. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(83)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd KG, Thuret F, Pilc A. Upregulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) B binding sites in rat frontal cortex: a common action of repeated administration of different classes of antidepressants and electroshock. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;235:191–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd KG, Zivkovic B, Sanger D, Depoorter H, Bartholini G. Fengabine, a novel antidepressant GABAergic agent. I. Activity in models for antidepressant drugs and psychopharmacological profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;241:245–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomer HP, Saunders JC, Kline NS. A clinic and pharmacodynamic evaluation of iproniazid as a psychic energizer. Psychiatry Res Rep. 1957;8:129–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lujan R, Shigemoto R, Kulik A, Juiz JM. Localization of the GABAB receptor 1a/b subunit relative to glutamatergic synapses in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2004;475:36–46. doi: 10.1002/cne.20160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luscher C, Jan LY, Stoffel M, Malenka RC, Nicoll RA. G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying K+ channels (GIRKs) mediate postsynaptic but not presynaptic transmitter actions in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1997;19:687–695. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcangio M, Da Silva H, Bowery NG. Plasticity of GABAB receptor in rat spinal cord detected by autoradiography. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;250:153–156. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90633-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall FH, Jones KA, Kaupmann K, Bettler B. GABAB receptors – the first 7TM heterodimers. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:396–399. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombereau C, Kaupmann K, Froestl W, Sansig G, Van Der Putten H, Cryan JF. Genetic and pharmacological evidence of a role for GABA(B) receptors in the modulation of anxiety – and antidepressant-like behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1050–1062. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombereau C, Kaupmann K, Gassmann M, Bettle B, Vanderputten H, Cryan JF. Altered anxiety and depression-related behaviour in mice lacking GABA(B(2)) receptor subunits. Neuroreport. 2005;16:307–310. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200502280-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Ishima T, Ishibashi Y, Yoshii T, Takashima T. Involvement of GABA(B) receptor systems in action of antidepressants: Baclofen but not bicuculline attenuates the effects of antidepressants on the forced swim test in rats. Brain Res. 1996;709:215–220. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa Y, Sasaki A, Takashima T. The GABA(B) receptor antagonist CGP36742 improves learned helplessness in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;381:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00567-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pałucha A, Brański P, Szewczyk B, Wierońska JM, Kłak K, Pilc A. Potential antidepressant-like effect of MTEP, a potent and highly selective mGluR5 antagonist. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:901–906. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp M, Moryl E, Willner P. Pharmacological validation of the chronic mild stress model of depression. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;296:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00697-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes RG, Agmo A. GABA and behavior: the role of receptor subtypes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16:145–170. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pibiri F, Carboni G, Carai MAM, Gessa GL, Castelli MP. Up-regulation of GABA(B) receptors by chronic administration of the GABA(B) receptor antagonist SCH 50,911. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;515:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilc A, Kłodzińska A, Brański P, Nowak G, Pałucha A, Szewczyk B, et al. Multiple MPEP administrations evoke anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilc A, Lloyd KG. Chronic antidepressants and GABA ‘B' receptors: a GABA hypothesis of antidepressant drug action. Life Sci. 1984;35:2149–2154. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(84)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilc A, Nowak G. GABAergic hypotheses of anxiety and depression: focus on GABAB receptors. Drugs Today (Barcelona) 2005;41:755–766. doi: 10.1358/dot.2005.41.11.904728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD, Anton G, Blavet N, Jalfre M. Behavioural despair in rats: a new model sensitive to antidepressant treatments. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978;47:379–391. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(78)90118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. Behavioral despair in mice: a primary screening test for antidepressants. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1977;229:327–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt GD, Bowery NG. Repeated administration of desipramine and a GABAB receptor antagonist, CGP 36742, discretely up-regulates GABAB receptor binding sites in rat frontal cortex. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:724–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond AM, Kelly JP, Leonard BE. Behavioural and neurochemical effects of dizocilpine in the olfactory bulbectomized rat model of depression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;58:355–359. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00259-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U, Crestani F, Mohler H. GABA(A) receptor subtypes: dissecting their pharmacological functions. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:188–194. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G, Gueorguieva R, Epperson CN, Wu YT, Appel M, Rothman DL, et al. Subtype-specific alterations of gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate in patients with major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:705–713. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G, Mason GF, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Hyder F, Petroff OA, et al. Reduced cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in depressed patients determined by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1043–1047. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.11.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G, Mason GF, Rothman DL, Krystal JH. Increased occipital cortex GABA concentrations in depressed patients after therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:663–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands SA, Reisman SA, Enna SJ. Effect of antidepressants on GABA(B) receptor function and subunit expression in rat hippocampus. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1489–1495. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieghart W. GABAA receptors: ligand-gated Cl− ion channels modulated by multiple drug-binding sites. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1992;13:446–450. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90142-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slattery DA, Desrayaud S, Cryan JF. GABAB receptor antagonist-mediated antidepressant-like behavior is serotonin-dependent. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:290–296. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.073536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl Sm. Psychopharmacology of Antidepressants. Martin Dunitz Ltd: London; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Thuault SJ, Brown JT, Sheardown SA, Jourdain S, Fairfax B, Spencer JP, et al. The GABA(B2) subunit is critical for the trafficking and function of native GABA(B) receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;68:1655–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. Validity, reliability and utility of the chronic mild stress model of depression: a 10-year review and evaluation. Psychopharmacology. 1997;134:319–329. doi: 10.1007/s002130050456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. Chronic mild stress (CMS) revisited: consistency and behavioural-neurobiological concordance in the effects of CMS. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;52:90–110. doi: 10.1159/000087097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]