Abstract

Objectives:

Simvastatin, a cholesterol-lowering drug, also stimulates oral bone growth when applied topically, without systemic side effects. However, the mechanisms involved in vivo are not known. We hypothesized that bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2), nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 are involved, based on prior in vitro evidence.

Material and Methods:

A rat bilateral mandible model, where 0.5 mg simvastatin in methylcellulose gel (SIM) was placed on one side and gel alone (GEL) on the other, was used to quantitate NO, COX-2 and BMP-2 (via tissue extraction, enzyme activity or immunoassay), and bone formation rate (BFR; via undecalcified histomorphometry). COX-2 and NOS inhibitors (N-398 and L-NAME, respectively) also were administered intraperitoneally.

Results:

SIM was found to stimulate local BMP-2, NO and regional BFR (p < 0.05), while NS-398 inhibited BMP-2 and BFR (p ≤ 0.05).

Conclusion:

These data suggest an association between simvastatin-induced BMP-2 and bone formation in the mandibular microenvironment, and the negative effect of COX-2 inhibitors on bone growth.

Keywords: simvastatin, BFR, BMP-2, COX-2

INTRODUCTION

Simvastatin is used to lower serum cholesterol. The topical application of this drug in the bone microenvironment also has been shown to stimulate new bone formation (1-4). Understanding the pathways of bone growth involved following simvastatin implantation may facilitate development of local therapeutic strategies designed to repair isolated bony anomalies such as periodontitis lesions and ridge defects, without systemic side effects. In vitro models have been used in an attempt to define mechanisms and pathways used by statins to induce bone growth. The most likely candidates from the preponderance of in vitro evidence appear to be nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) (1, 5).

Statins also have been shown to increase the inducible cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 and subsequent prostaglandin (PG)E2 (6), thereby increasing collagen synthesis (7) and BMP-2-mediated osteoblast differentiation in vitro (8). Local administration of PGE2 to rat tibia has been shown to induce new woven bone (9) and increase type I collagen and fibronectin in osteoblasts (10), similar to what was seen with simvastatin in vivo (3). However, little data are available as to whether BMP, NOS, or COX/PGE2 are involved in simvastatin-induced bone growth within the bone microenvironment. The main aim of this study was to confirm the knowledge from in vitro studies that simvastatin induces the aforementioned mediators when applied in an in vivo model. We hypothesized that when simvastatin was applied adjacent to rat mandibular periosteum, the production of candidate mediators (BMP-2, NO, COX-2) would increase in the vicinity, as well as regional bone formation rate. Conversely, inhibiting NOS (L-NAME) and COX-2 (NS-398) pathways (no practical in vivo BMP-2 inhibitors are available) would cause reduction of involved local mediator levels and subsequent bone formation rates in the mandible.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Rat Bilateral Mandible Model and Local Delivery System

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee at the University of Nebraska. A bilateral mandible model using retired-breeder female Sprague-Dawley rats (approximately 300 g, ≥ one year old) was used as described previously (3). Briefly, simvastatin (Merck & Co., Rahway, NJ) and control sides were selected randomly for each animal. Each side received an impermeable, biocompatible polylactic acid (PLA) dome carrying either 30 μl of a methylcellulose gel-0.5 mg simvastatin mixture (SIM) or gel alone (GEL). Each dome was inserted supraperiosteally onto the lateral surface of the rat mandible under sedation.

Phase I of the study was designed to test the hypothesis that locally implanted SIM would increase COX-2, NO and BMP-2 in adjacent tissues. Rats systemically treated only with vehicle used for blocking experiments (unblocked control; intraperitoneal [IP] injections of 1 part ethanol/5 parts sterile saline; n = 20) were analyzed for BMP-2, COX-2 and NO activity after euthanasia (CO2 asphyxiation) at days 3, 7 or 14 post-implantation.

Phase II addressed the hypothesis that inhibiting COX-2 and NOS would reduce SIM-induced local mediator levels. Rats were blocked for COX-2 with NS-398 (Cayman Chemical Co., Ann Arbor, MI; IP 2 mg/kg/day; n = 10) or for NO with L-NAME (Cayman; IP 25 mg/kg/day; n = 10) and euthanized at days 7 or 14 post-implantation. These times were based on: day 7 – Peak osteoblast activity from a previous study (3), and immediately after completion of blocking-drug therapy; day 14 – Phase I peak COX-2 and NO values for SIM versus GEL and near beginning of calcein labeling (Phase III). Drugs were administered on the following schedule: Day [−1] (IP blocking agent/vehicle); Day [0] (SIM/GEL implants); Days [+1 through +6] (IP blocking agent/vehicle). L-NAME and NS-398 concentrations were based on past literature showing blocking of appropriate pathways and reduction of inflammation in rats (11, 12).

Phase III of the study was used to analyze bone formation rates in animals treated as in Phases I and II, but labeled with calcein at days 17 and 24 post-implantation and euthanized at day 27 (n = 30). This phase allowed testing the hypothesis that inhibiting NOS and COX-2 pathways would reduce SIM-induced bone formation rates.

Biochemical Analyses

The tissue samples harvested from both GEL and SIM sides for analysis of BMP-2, COX-2 and NO consisted of the portions of the masseter muscle and periosteum which enveloped the PLA dome. Each tissue sample was cut into approximately one gram specimens, homogenized (Kontes tissue grinder #21, Kontes Scientific Glassware, Vineland, NJ) into phosphate-buffered saline and protease inhibitor cocktail (P2714, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and centrifuged. Commercially-available kits were used to evaluate COX-2 (Cayman) and NO (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) activities, as well as BMP-2 (R & D Systems) and total protein (BCA; Pierce, Rockford, IL) concentrations. COX values were based on colorimetric evaluation of the peroxidase activity of cyclooxygenase, while NO values were based on colorimetric detection of nitrite as an azo dye product of the Griess Reaction. BMP-2 values were determined using a sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique and BCA used bicinchoninic acid for colorimetric quantitation of total protein.

Histomorphometry

At days 17 and 24 following dome implantation, the rats were injected with 0.3 ml (8 mg/kg) calcein to label new bone mineralization. At day 27, the rats were euthanized and mandibles were surgically removed and prepared for undecalcified histomorphometry as previously described (13). Briefly, mandibles immediately were immersed in 70% alcohol for a minimum of 48 h. After initial fixation, mandibles were dissected free of soft tissue. The bone posterior to the implanted membrane was cut away perpendicular to the occlusal plane for making subsequent transverse serial sections. Samples were placed into Villanueva stain for 72 h and returned to 70% alcohol. During the next 14 days, the specimens were dehydrated in graded ethanol and acetone, and then embedded individually in modified methyl methacrylate. All specimens were coded so that they could be evaluated by two independent examiners without knowledge of experimental conditions. Eighty μm thick cross-sections of mandibles under the domes were viewed using a light/epifluorescent microscope and a video camera interfaced with the BIOQUANT OSTEO software (R & M Biometric, Nashville, TN). Multiple measurements in the inferior 2 mm of the mandible were taken of bone perimeter (total, lateral, medial, and inferior surfaces) at 40X; single, double, and woven fluorescent label perimeter (sLPm., dLPm., and Wo.Pm.) found on the total bone perimeter (BPm) at 200X; and interlabel thickness (IrLTh.) at 400X. Calculations then were made with these measurements to determine mineral apposition rate (MAR = IrLTh/7 days), lamellar bone formation rate (LamBFR = [0.5sLPm. + dLPm.]/BPm. *MAR), woven bone formation rate (WBFR = WoPm./BPm. * 5 μm/d), and total bone formation rate (BFR = Lam BFR + WBFR) (14). The woven bone was seen either as a massive expanse or as a continuum from rapid lamellar formation; in either case, the rate of formation was not measurable directly. Since the woven formation was more rapid than lamellar, MAR was estimated at 5 μm/d based on peak lamellar MAR. We measured a total of 420 bone surfaces (including lateral, medial, inferior) and found eight surfaces with an average MAR between 4 and 5 μm/d and 3 surfaces with an average of 5 or more μm/d.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyzed included ratios of biochemical markers divided by total protein in each tissue sample, to adjust for differences among individual samples. Comparisons of biochemical markers among treatment groups, time periods, and the interaction of treatment groups and time periods were conducted using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Histomorphometry was analyzed using a mixed model analysis of variance for difference between groups due to blocking agent, within animal due to gel or simvastatin implant, and the interaction of simvastatin and blocking agent. Significant effects were tested between groups with Dunnet's post hoc test and within animals with paired sample t-test.

RESULTS

Biochemical Data

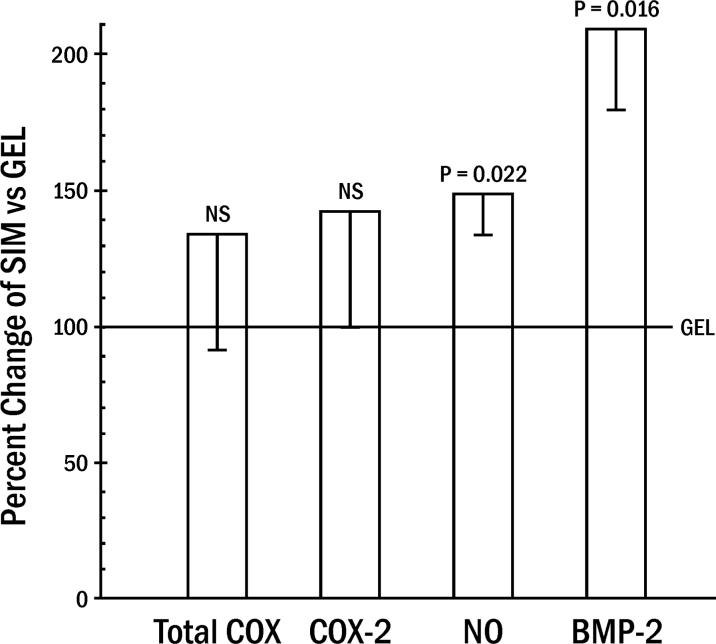

Unblocked rats tolerated the implants well, gaining an average of 3.7 ± 3.1 g (mean ± standard error) over the experimental period. Rats subjected to L-NAME and NS-398 also continued to thrive and gain weight (18.1 ± 4.5 g). Rats not treated with systemic blocking agents (L-NAME or NS-398) were analyzed first to determine how mediator levels in tissue surrounding SIM compared to those adjacent to GEL in the same animal (Figure 1). A significant group effect from ANOVA averaged for all days: (day 3, 7, and 14) demonstrated that both local NO activity and BMP-2 protein were upregulated by SIM. The primary impact of SIM enhancement of BMP-2 over GEL occurred at day 3, while NO increases were apparent at days 3 and 14 (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Local production of mediators (cyclooxygenase [COX] and nitric oxide [NO] activity; bone morphogenetic protein [BMP]) by simvastatin, adjusted for total protein in the tissue sample. Percent change in simvastatin in gel dome (SIM) values relative to domes with gel alone (GEL = 100%) in unblocked animals (means ± standard errors averaged for all days [3, 7, 14] post-dome implantation; averaged 7 animals/day).

Table 1.

Mean Ratios of BMP-2 Protein or COX-NO Activity Divided by Total Protein (BCA) in Peri-Implant Tissue (mean ± standard error)

| Day | Treatment | BMP-2/BCA (pg/μg) | COX-2/BCA (Activity U/μg) | NO/BCA (Nitrite nmo1/μg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | SIM | 1.569 ± 0.264 | 0.095 ± 0.120 | 1.873 ± 0.291 |

| GEL | 0.598 ± 0.264 | 0.057 ± 0.120 | 1.165 ± 0.291 | |

| 7 | SIM | 0.285 ± 0.173 | 0.137 ± 0.078 | 0.600 ± 0.190 |

| GEL | 0.245 ± 0.173 | 0.086 ± 0.078 | 0.580 ± 0.190 | |

| SIM + NS-398 | 0.273 ± 0.097 | 0.098 ± 0.152 | C | |

| SIM + L-NAME | 0.212 ± 0.097 | C | 0.694 ± 0.227 | |

| 14 | SIM | 0.536 ± 0.145 | 0.293 ± 0.066 | 1.426 ± 0.159 |

| GEL | 0.300 ± 0.145 | 0.221 ± 0.066 | 0.859 ± 0.159 | |

| SIM + NS-398 | 0.264 ± 0.063 | 0.179 ± 0.010 | C | |

| SIM + L-NAME | 0.308 ± 0.068 | C | 0.994 ± 0.160 |

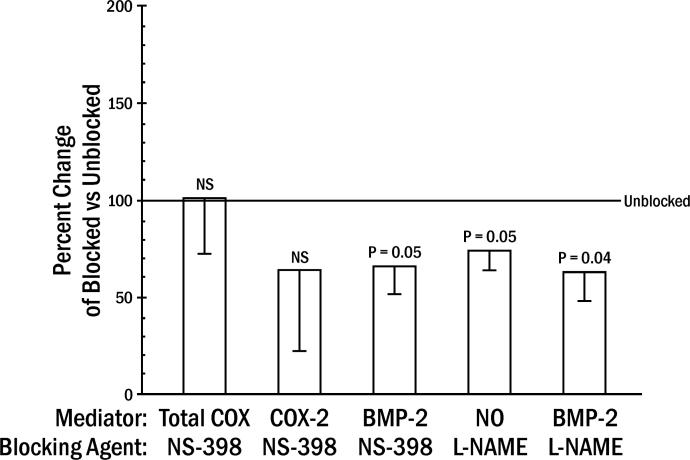

L-NAME significantly reduced SIM-induced NO activity at day 14, but did not eliminate it (Figure 2; Table 1), while NS-398 reduction of COX-2 activity failed to reach significance. Both NS-398 and L-NAME did significantly reduce BMP-2 levels (Figure 2), with the primary effect occurring on day 14 (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of SIM-induced mediators by blocking agents. Percent change in SIM for COX-2, BMP-2 and NO in animals receiving systemic blocking agent (NS-398 for COX-2 or L-NAME for NO synthase: Blocked) divided by animals receiving no systemic blocking agent (Unblocked from experiments in Figure 1 = 100%) (means ± standard errors averaged for days 7 and 14 for COX-2 and BMP-2, and day 14 for NO; averaged 5 animals/day).

Bone Formation Rate

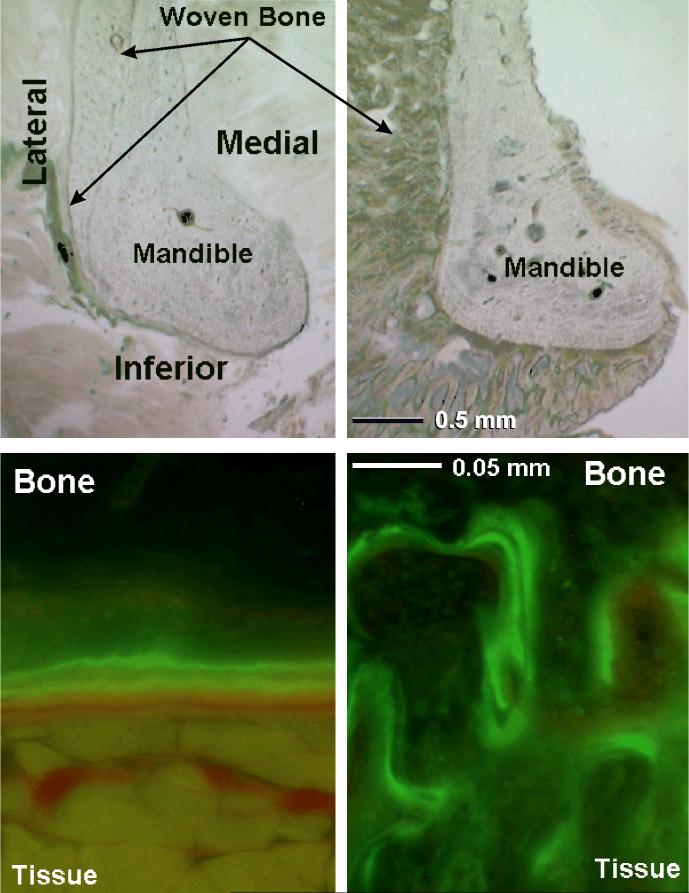

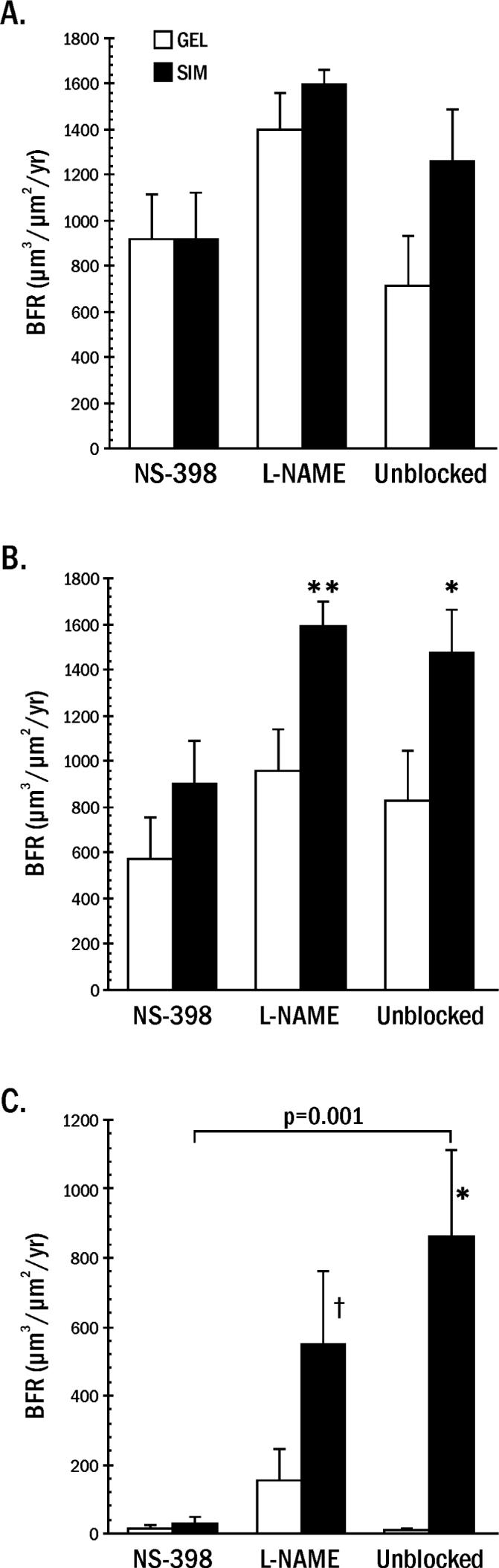

BFR was highest in both GEL and SIM on the lateral surface of the mandible adjacent to the dome and along the inferior border of the mandible several mm away from dome placement (Figures 3, 4). There were no differences between the control gel and simvastatin implants on the lateral surface for blocked or unblocked groups. BFR was elevated in the unblocked and L-NAME-treated animals for simvastatin compared to gel implants on the inferior and medial surfaces (Figure 4). While NS-398 treatment did not significantly reduce the COX-2 response to simvastatin (Figure 2), these animals showed no difference in BFR between simvastatin and gel implants on any surface, and the formation rates on the simvastatin and gel-treated sides were similar to those of gel treatment in the unblocked group. NS-398 nearly abrogated medial SIM BFR (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs from one animal with gel control on the left and simvastatin on the right. Light microscope view (top) at 20X and ultraviolet light view of the inferior surface (bottom) at 200X. Calcein label of new bone formation shows inferior surface double label in the gel section and irregular woven bone in the simvastatin section. The gel dome caused limited lateral woven bone and good double label on the inferior surface. The simvastatin dome caused massive lateral and inferior woven bone, and limited medial woven bone.

Figure 4A.

Bone formation rate (BFR) on the lateral bone surface adjacent to the gel alone (GEL) and gel + simvastatin implants (SIM). Animals (averaged 10/group) were treated with vehicle (Unblocked), or NS-398 or L-NAME to block the COX-2 or NOS response to simvastatin, respectively. 4B. Bone formation rate on the inferior bone surface after GEL and SIM implants. Animals were treated with NS-398, L-NAME or vehicle to block the response to simvastatin. Simvastatin was different from gel implant at *p = 0.014, **p = 0.024. 4C. Bone formation rate on the medial bone surface after GEL and SIM implants. Animals were treated with NS-398, L-NAME, or vehicle to block the response to simvastatin. The bone response to simvastatin was lower in NS-398 than unblocked mandibles (bracket p = 0.001). Simvastatin was different from gel implant at * p = 0.008, ⊥ trend at p = 0.08.

DISCUSSION

The implantation of SIM or GEL doses, or the intraperitoneal injections of L-NAME or NS-398 over a 7-day period, did not appear to impair the animals' ability to eat or function, as all rat groups (mature females) gained weight from baseline. The greater weight gain in the rats treated with blocking drugs may have been due to the shorter acclimation time following shipping until baseline in the blocked rats (4 days) compared to unblocked rats (14 days). This may have allowed weight lost during shipping to be regained during the experiment, thereby resulting in more weight gain in the blocked groups. However, the impact of this systemic weight gain likely had little influence on local sample weight, total protein or simvastatin metabolism because: 1) all specimens were dissected at harvest to be approximately the same size (1 gram), a small portion of the 300 g rat; 2) sample weights did not vary significantly from blocked to unblocked rats; and 3) all animals received an equivalent dose of SIM which did not affect the GEL bone formation (Figure 4C).

Simvastatin applied adjacent to mandibular periosteum significantly upregulated both BMP-2 and NO activity in the surrounding tissue (Figure 1). This effect is consistent with in vitro studies showing statin stimulation of BMP-2, eNOS and cNOS (1, 5, 15-18), and confirms the ability of simvastatin to stimulate BMP-2 and NO in vivo. NO activity tests used in this study provided a practical and functional method to assess NOS involvement, but lacked the ability to identify NOS forms (eNOS, cNOS), which is a limitation of the protocol. Review of the literature indicates that the current study represents the first quantitation of BMP-2, NO and COX-2 activity in the bone microenvironment resulting from simvastatin application. The early appearance of BMP-2 (day 3) is similar to first immunolocalization of BMP-2 (day 4) around simvastatin/collagen in a rabbit parietal bone graft model (4).

Seven IP doses of L-NAME at 25 mg/kg/day caused a significant reduction in NO activity in the mandibular bone microenvironment (Figure 2). While other reports of L-NAME effects on bone NO activity associated with simvastatin are lacking, previous studies have shown that a single dose of L-NAME in a range of 5−25 mg/kg caused a dose-related inhibition of carrageenan-induced hindpaw edema in the rat (12). No studies have shown an effect of NS-398 on simvastatin-induced COX activity, but NS-398 doses around the 2 mg/kg used in the current study have been shown to block PG synthesis in carrageenan-induced subcutaneous rat air pouch inflammation (19). Importantly, a slightly smaller NS-398 dose, but similar protocol, has been shown to inhibit osteoblast numbers and bone growth in the simvastatin implant, rat mandible model (3). These investigators also showed reduction in the amount of inflammatory infiltrate around the SIM implants and bone. COX-2 inhibitors are classified as anti-inflammatory drugs and prostaglandin E is a primary inflammatory mediator reduced by COX-2 inhibitors. PGE also has been shown to promote bone formation in the jaw (20) and COX-2 activity was found necessary for bone fracture healing (21), so COX-2/PGE reduction resulting from COX-2 inhibitors may inhibit this bone growth. It is, therefore, likely that simvastatin-induced bone growth and COX-2-induced inflammation are intertwined. However, the IP dose of COX-2 inhibitor used in this study was not able to reduce COX-2 activity significantly around the SIM implants, due to high variability. Statistical significance may have been achieved by altering the NS-398 dose or increasing the number of rats.

Interestingly, BMP-2 in the SIM bone microenvironment was reduced after systemic administration of NS-398 (66% of unblocked levels) and L-NAME (63%), neither of which were selected to specifically block BMP-2 (Figure 2). These findings are supported by in vitro evidence that NS-398 suppresses BMP-2 expression in human mesenchymal stem cells (22). BMP-2 also has been shown to reverse the negative effects of a COX inhibitor (ketorolac) on bone formation during posterolateral intertransverse process spine fusion healing in rabbits (23). To our knowledge, the current study represents the first report of COX-2 or NOS inhibitors affecting statin-induced BMP-2 levels in the bone microenvironment.

The use of randomized contralateral mandible treatments within an animal allowed the separation of surgical manipulation and simvastatin effects. Surgical implantation of the GEL and SIM domes had a local excitatory effect on the adjacent lateral bone surface that resulted in rapid woven and lamellar bone formation in both groups, thereby obscuring the simvastatin effect. Greater than 65% of the forming surface was comprised of woven bone. The new bone area was generally greater on the SIM side (Figure 3), consistent with our earlier reports (3). The surgical reaction dissipated with distance from the dome. The medial surface, which was over 5 mm distant from the dome, demonstrated the least response to GEL with minimal BFR, yet SIM BFR remained relatively high (Figure 4C). Lamellar bone formation as part of normal bone remodeling represented a higher percentage of forming surface, and woven bone was limited in this area. These data demonstrated a regional effect of simvastatin implants. That is, a simvastatin implant may affect bone formation in a limited area beyond that in direct contact with the implant dome, but not systemically. This phenomenon may have therapeutic implications in regenerating isolated bony defects such as those found with periodontitis or alveolar ridge defects prior to dental implant placement. While observations in the current study excluded any evaluation of endosteal bone, the primary goal of periodontal osteogenic procedures is to add dense, supportive bone onto the periosteal surface of the intrabony or ridge defect. Bone in the current study resembled cortical bone more than trabecular bone. This would seem to contradict Oxlund et al. (24) who found that simvastatin administered perorally to mature female rats increased vertebral cancellous, but not cortical bone. However, the current study applied simvastatin adjacent to cortical bone periosteum of the mandible, and trabecular bone was sparse in this area and relatively inaccessible to the drug. These contrasting findings emphasize how topical statin delivery differs from traditional oral dosing.

Evaluation of the inferior and medial bone surfaces showed that L-NAME did not reduce BFR (Figure 4), even though L-NAME did significantly reduce NO activity (Figure 2). However, NS-398 clearly blocked simvastatin-induced BFR on the medial mandibular surface (p = 0.001), and, on the inferior surface, it reduced the difference between SIM and GEL to where it was no longer significant. This is consistent with the reduction in overall bone area and osteoblast surface reported earlier using a similar SIM mandibular model (3). COX-2 inhibition also has been shown to decrease loading-induced BFR on the periosteal surface of the ulna (25), fracture healing (26) and osteoblast numbers in vivo (27). In COX-2 knockout mice, intramembranous bone formation from fibroblast growth factor-1 was reduced 60% compared to wild type or COX-1 knockouts (28).

Results of the current study show that, even though this low dose of NS-398 failed to significantly reduce COX-2 activity in the vicinity, it still inhibited bone formation. This suggests COX-2 inhibitors may affect bone by altering additional mediators to those traditionally associated with inflammatory bone turnover. BMP-2 would be a good candidate, a strong mediator of in vitro statin-induced bone formation (1, 5). SIM upregulated both BMP-2 and bone formation rate, and N-398 downregulated BMP-2 using the same protocol which dramatically reduced simvastatin-induced bone formation rate. These results suggest an association between simvastatin-induced BMP-2 production and bone growth in the microenvironment of the mandibular periosteum, and the negative impact of COX inhibitors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the USPHS Research Grant DE-015096 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892. Simvastatin was supplied by Merck & Co. The authors thank Dr. David Marx for statistical analysis, Marian Schmid for technical assistance with animal procedures and biochemical tests, Dr. Jeffrey Payne for his critical review of this manuscript, Susan McCoy for manuscript preparation and Kim Theesen for developing the figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mundy G, Garrett R, Harris S, Chan J, Chen D, Rossini G, et al. Stimulation of bone formation in vitro and in rodents by statins. Science. 1999;286:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thylin MR, McConnell JC, Schmid MJ, Reckling RR, Ojha J, Bhattacharyya I, et al. Effects of statin gels on murine calvarial bone. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1141–1148. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.10.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stein D, Lee Y, Schmid MJ, Killpack B, Genrich MA, Narayana N, et al. Local simvastatin effects on mandibular bone growth and inflammation. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1861–1870. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong RW, Rabie AB. Early healing pattern of statin-induced osteogenesis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;43:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrett IR, Gutierrez G, Mundy GR. Statins and bone formation. Curr Pharm Design. 2001;7:715–736. doi: 10.2174/1381612013397762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J-C, Huang K-C, Wingerd B, Wu W-T, Lin W-W. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors induce COX-2 gene expression in murine macrophages: role of MAPK cascades and promoter elements for CREB and c/EBPβ. Exp Cell Res. 2004;301:305–319. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hakeda Y, Nakatani Y, Kurihara N, Ikeda E, Maeda N, Kumegawa M. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates collagen and non-collagen protein synthesis and prolyl hydroxylase activity in osteoblastic clone MC3T3-E1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1985;126:340–345. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takiguchi T, Kobayashi M, Nagashima C, Yamaguchi A, Nishihara T, Hasegawa K. Effect of prostaglandin E2 on recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2-stimulated osteoblastic differentiation in human periodontal ligament cells. J Periodont Res. 1999;34:431–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang RS, Liu TK, Lin-Shiau SY. Increased bone growth by local prostaglandin E2 in rats. Calcif Tissue Int. 1993;52:57–61. doi: 10.1007/BF00675627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang C-H, Yang R-S, Fu W-M. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates fibronectin expression through EP1 receptor, phospholipase C, protein kinase Cα and c-Src pathway in primary cultured rat osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22907–22916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payá M, Pastor PG, Coloma J, Alcaraz MJ. Nitric oxide synthase and cyclo-oxygenase pathways in the inflammatory response induced by zymosan in the rat air pouch. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1445–1452. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Handy RL, Moore PK. A comparison of the effects of L-NAME, 7-N1 and L-NIL on carrageenan-induced hindpaw oedema and NOS activity. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;123:1119–1126. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwaniec UT, Haynatzki GR, Fung YK, Akhter MP, Haven MC, Cullen DM. Effects of nicotine on bone and calciotropic hormones in aged ovariectomized rats. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2002;2:469–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, et al. Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. J Bone Miner Res. 1987;2:595–610. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650020617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sugiyama M, Kodama T, Konishi K, Abe K, Asami S, Oikawa S. Compactin and simvastatin, but not pravastatin, induce bone morphogenetic protein-2 in human osteosarcoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2000;271:688–692. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeda T, Matsunuma A, Kawane T, Horiuchi N. Simvastatin promotes osteoblast differentiation and mineralization in MC3T3-E1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2001;280:874–877. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.4232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda T, Matsunuma A, Kurahashi I, Yanagawa T, Yoshida H, Horiuchi N. Induction of osteoblast differentiation indices by statins in MC3T3-E1 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2004;92:458–471. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McFarlane SI, Muriyappa R, Francisco R, Sowers JR. Clinical review 145: Pleiotropic effects of statins: lipid reduction and beyond. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1451–1458. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masferrer JL, Zweifel BS, Manning PT, Hauser SD, Leahy KM, Smith WG, et al. Selective inhibition of inducible cyclooxygenase 2 in vivo is anti-inflammatory and nonulcerogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3228–3232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vrotsos Y, Miller SC, Marks SC., Jr Prostaglandin E – a powerful anabolic agent for generalized or site-specific bone formation. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2003;13:255–263. doi: 10.1615/critreveukaryotgeneexpr.v13.i24.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon AM, Manigrasso MB, O'Conner JP. Cyclooxygenase 2 function is essential for bone fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:963–976. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arikawa T, Omura K, Morita I. Regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-2 expression by endogenous prostaglandin E2 in human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2004;200:400–406. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin GJ, Jr, Boden SD, Titus L. Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 overcomes the inhibitory effect of ketorolac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), on posterolateral lumbar intertransverse process spine fusion. Spine. 1999;24:2188–2193. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199911010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oxlund H, Dalstra M, Andreassen TT. Statin given perorally to adult rats increases cancellous bone mass and compressive strength. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:299–304. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-2027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Burr DB, Turner CH. Suppression of prostaglandin synthesis with NS-398 has different effects on endocortical and periosteal bone formation induced by mechanical loading. Calcif Tissue Int. 2002;70:320–329. doi: 10.1007/s00223-001-1025-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harder AT, An YH. The mechanisms of the inhibitory effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on bone healing: a concise review. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:807–815. doi: 10.1177/0091270003256061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodman S, Ma T, Trindade M, Ikenoue T, Matsuura I, Wong N, et al. COX-2 selective NSAID decreases bone ingrowth in vivo. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:1164–1169. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Schwarz EM, Young DA, Puzas JE, Rosier RN, O=Keefe RJ. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates mesenchymal cell differentiation into the osteoblast lineage and is critically involved in bone repair. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1405–1415. doi: 10.1172/JCI15681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]