Abstract

The current model for HIV-1 envelope-coreceptor interaction depicts the V3 stem and bridging sheet binding to the CCR5 N-terminus while the V3 crown interacts with the second extracellular loop, which is the coreceptor domain that appears to be relatively more important for fusion and infection. Our prediction based on this model is that mutations in the V3 crown might consequently have more effects on cell-cell fusion and virus entry than mutations introduced in the V3 stem and C4 region. We performed alanine-scanning of the V3 loop and selected C4 residues in the JRFL envelope and tested the capacity of the resulting mutants for CCR5 binding, cell-cell fusion, and virus infection. Our cross comparison analysis revealed that residues in C4 and in both the V3 stem and crown were important for CCR5 binding of gp120 subunits. Contrary to our prediction, mutations in the V3 crown had less effect on membrane fusion than mutations in the V3 stem. The V3 stem thus appears to be the most important region for CCR5 utilization since it affected both coreceptor binding and subsequent fusion and viral entry. Our data raises the possibility that some residues in the V3 crown and in C4 may play distinct roles in the binding and fusion steps of envelope-coreceptor interaction.

Keywords: HIV-1 envelope, V3 loop, Bridging Sheet, CCR5 coreceptor

Introduction

Entry of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) into target cells generally requires sequential interaction between the virus envelope glycoprotein gp120, the primary receptor CD4, and a seven-transmembrane chemokine coreceptor. HIV-1 gp120 first binds to CD4 and undergoes conformational changes that allow the envelope protein to interact with chemokine coreceptors, mainly CCR5 or CXCR4 (Trkola et al., 1996; Wu et al., 1996). Binding of the coreceptor then triggers additional conformational changes in gp41, leading to fusion of virus and cell membranes and subsequent viral entry (Weiss, 2003).

The current model for coreceptor interaction based on HIV-1 subtype B is one in which the C4 and the V3 stem bind to the sulfated N-terminus (Nt) of CCR5 while the V3 crown interacts with other parts of CCR5, mainly the second extracellular loop (ECL). The features of gp120 that are important for CCR5 interaction have been defined primarily by crystal structures of CD4-bound gp120 core with and without an intact V3 loop (Chen et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2005; Kwong et al., 1998) and mutagenesis involving the direct binding of monomeric gp120-CD4 complexes to CCR5-expressing cells or to CCR5-derived sulfopeptides (Cormier and Dragic, 2002; Cormier et al., 2001; Rizzuto and Sodroski, 2000; Rizzuto et al., 1998).

Studies based solely on monomeric gp120 binding assays are not sufficient to provide a comprehensive analysis of functional gp120-CCR5 interaction. In fact, three different mutations in the coreceptor binding domains have been reported to yield a discordance between high affinity binding of gp120 and the ability of the envelope to mediate cell-cell fusion and subsequent viral entry (Hu et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2000; Reeves et al., 2004). A P438A mutation in the C4 region, a D324A mutation in the V3 stem, and a P311A mutation in the V3 crown all disrupted CCR5 binding, but did not alter the usage of CCR5 in fusion and infection experiments compared to wild-type (WT) envelope (Hu et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2000; Reeves et al., 2004). Whether this observed phenotype is limited to just these three residues or whether it is a more general phenomena has not been addressed. Furthermore, it has been shown that CCR5 structures that support binding and fusion map to overlapping but distinct regions on the coreceptor, with the Nt of CCR5 more important for binding while the ECLs are more important for fusion and infection (Doranz et al., 1997). In light of this, it is conceivable that different regions of the V3 loop and the C4 domain may play overlapping but distinct roles in the binding and fusion steps of gp120 interaction with CCR5 as well.

Here, we present the first systematic cross-comparison study of the role of individual V3 and C4 residues in CCR5 binding and functional consequences on cell-cell fusion and viral entry. We sought to test the hypothesis that mutations introduced to residues in the V3 crown have more effect on cell-cell fusion than mutations in the V3 stem and C4, despite all of these regions contributing to CCR5 binding. Our analysis indicated that binding of monomeric gp120 to CCR5 is susceptible to changes in all three regions: C4 and both the V3 stem and crown. However, contrary to our prediction, envelope-mediated cell-cell fusion is notably affected by only specific substitutions in the V3 stem, rather than the V3 crown.

Results

CCR5 utilization by a chimeric HIV-1 subtype B molecular clone

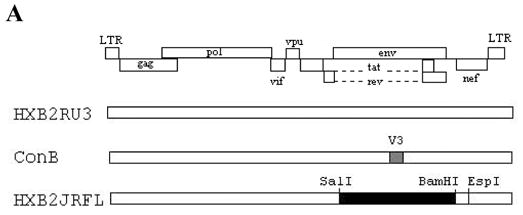

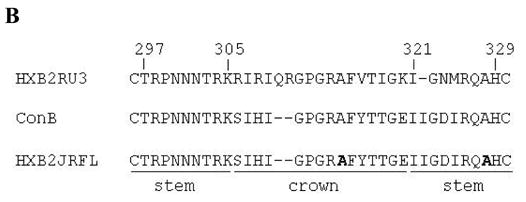

We focused our analysis on the HIV-1 subtype B R5 isolate JRFL to maintain consistency with previous studies (Cormier and Dragic, 2002; Cormier et al., 2001). An HIV-1 chimeric provirus containing the JRFL envelope in the genetic background of the X4 infectious molecular clone HXB2-RU3 was the starting point for our mutagenic studies (Fig. 1A). The ability of this chimeric construct, designated HXB2-JRFL, to use CCR5 as an entry coreceptor was demonstrated in infection assays using the cell lines U87-CD4-CCR5 and U87-CD4-CXCR4, which stably express CD4/CCR5 and CD4/CXCR4, respectively. Equivalent amounts of viruses were used to infect the target cells, and p24 levels in the infected culture supernatants were determined seven days post-infection. In this experiment, Con B, a previously described molecular clone that contains the consensus V3 sequence of HIV-1 subtype B non-syncitium inducing viruses in the background of HXB2-RU3 and uses CCR5 as its entry coreceptor (Trujillo et al., 1996), served as the positive control, while HXB2-RU3 was included as a negative control. As shown in Fig. 1C, ConB replicated to a much higher level in CCR5-positive cells, while HXB2-RU3 replicated efficiently only in CXCR4-positive cells. The chimeric virus HXB2-JRFL infected only cells expressing CCR5, which confirmed previous observations that the envelope protein contains important determinants of coreceptor utilization, and that replacing the V3 region of an X4 virus with that from an R5 isolate is sufficient to confer coreceptor switching (Wang et al., 1998). The HXB2-JRFL chimeric provirus was subsequently used in this study as the parental clone to generate gp120 mutants for further analysis.

Fig. 1.

(A) Schematic drawing of the proviral clones used in this study. The open rectangle represents sequences from the subtype B molecular clone HXB2RU3. The hatched rectangle in ConB represents the consensus V3 sequence of HIV-1 subtype B NSI viruses in the HXB2RU3 backbone. The filled rectangle in HXB2-JRFL represents the SalI-BamHI env fragment (positions 5789 to 8451) derived from the R5 subtype B strain JRFL. The EspI (8840) site used in the cloning procedures is also indicated. (B) V3 sequences of the proviral clones, based on the JRFL numbering. Stem (positions 297–305 and 321–329) and crown (positions 306–320) regions are indicated. Naturally occurring alanines in the V3 of HXB2-JRFL that were mutated to glycine are indicated in bold-face. (C) Coreceptor utilization by the proviral clones as measured by p24 levels in virus-infected cultures at day 7. The results represent the means and standard deviations (SD) of data from three independent experiments.

Construction of HXB2-JRFL envelope mutants

To generate a panel of envelope mutants, alanine-scanning mutagenesis of the entire V3 loop and selected C4 residues in the HXB2-JRFL provirus was conducted. A total of 33 V3 mutants were made by introducing alanine substitutions to each V3 residue from positions 297 to 329, with the two naturally occurring alanines at positions 314 and 328 replaced with glycine (Fig. 1B). Alanine was chosen as a substituent because its small nonpolar methylene side chain is less likely to impose severe constraints on gp120 and contributes little to protein-protein interactions. In this study, we subdivided the V3 loop into two domains as functionally defined by Cormier et al. (2002) (Fig. 1B). Therefore, a total of 18 V3 stem mutations (positions 297–305 and 321–229) and 15 V3 crown mutations (positions 306–320) were generated. Five C4 mutants were also constructed in a similar fashion at positions 420, 421, 422, 438 and 441. These mutant proviruses were used for the cell-cell fusion and virus infection assays. Soluble gp120 expression vectors derived from these envelope mutants containing corresponding V3 and C4 substitutions were also constructed for subsequent use in the CCR5 binding assay.

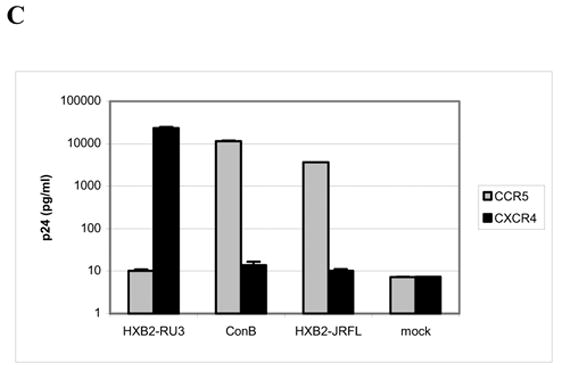

Effects of mutations on cell-cell fusion

In order to determine gp120 elements that are important for CCR5-dependent membrane fusion, we quantitatively assessed the ability of the mutant envelope glycoproteins to fuse with U87-CD4-CCR5 cells using a sensitive reporter gene activation assay (Nussbaum, Broder, and Berger, 1994). β-Gal activity produced by the mutant envelope clones was compared with that of the WT, HXB2-JRFL, to score for the relative efficiency in mediating cell-cell fusion. As shown in Fig. 2, all the V3 mutations that markedly reduced fusogenic activity were located in the V3 stem. Alanine substitutions of six amino acids (R298A, T303A, I321A, G323A, D324A, and R326A) in the N- and C-terminal ends of the V3 loop reduced the ability of the envelope to mediate fusion by more than 50% (mean plus one standard deviation below 50% compared to WT). Three additional mutations (N301A, R304A, and I322A) in the V3 stem also decreased fusion by approximately 50%. In contrast, all substitutions in the V3 crown allowed the envelope to maintain fusogenic activity with moderate to high efficacy (60–100% of WT). Out of the five highly conserved C4 residues that were previously implicated in CCR5 binding (Rizzuto and Sodroski, 2000), only the I420A mutation reduced fusion by more than 50%. It is noted, however, that P438A decreased the ability of the envelope to fuse by about 50%, and a moderate reduction was also observed for K421A. Taken together, these data suggest that gp120 residues in the V3 stem are the most crucial for mediating cell-cell fusion, although C4 residues can also modulate fusogenic activity.

Fig. 2.

Effect of V3 and C4 mutations on CCR5-dependent cell-cell fusion as measured by a reporter gene activation assay. β-Gal activity is expressed as a percentage of that seen with the wild-type (WT) clone, HXB2-JRFL. White bars indicate values (mean plus one standard deviation) less than 50%. Gray bars indicate mean values that are 50%. Data shown represent the means and standard deviations of data from at least three independent experiments.

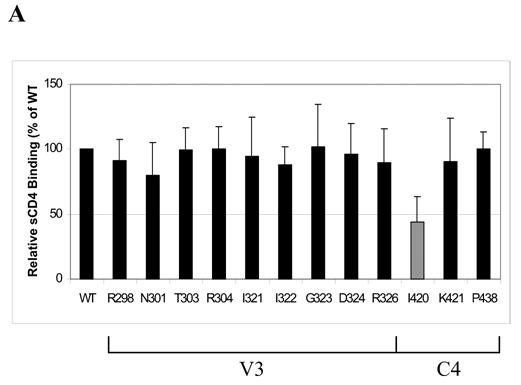

Effects of mutations on CD4 binding

It is conceivable that mutations in V3 and C4 can affect gp120 interaction with CCR5 indirectly. Since binding of gp120 to CD4 is often a prerequisite step to CCR5 interaction, we wanted to verify that introducing V3 and C4 mutations in gp120 did not affect CD4 binding. ELISA was used to assay the binding of gp120 to soluble CD4 (sCD4) for the twelve mutants that reduced cell-cell fusion by approximately 50% or more. As shown in Fig. 3A, all V3 mutants retained the ability to bind sCD4 efficiently (80–100% of WT), which is in agreement with previous reports that V3 residues are not involved in CD4 binding (Wyatt et al., 1993). The I420A mutation in the C4 region, however, reduced sCD4 binding by more than two-fold (44% of WT), suggesting that poor CD4 binding may partly account for the observed derease in fusion by this mutant clone.

Fig. 3.

(A) Effect on gp120-sCD4 binding, as measured by ELISA, for V3 and C4 mutations that were found to reduce cell-cell fusion by approximately 2-fold or more. The gray bar indicates a mean value less than 50% of WT. Data shown represent the means and SD of data from three independent experiments. (B) A representative western blot of envelope proteins in viral lysates for V3 and C4 mutants that decreased CCR5-dependent cell fusion by approximately 2-fold or more. Pooled sera from individuals infected with HIV-1 subtype B was used to detect the expression of envelope proteins. The positions of the gp120 and p24 bands are labeled.

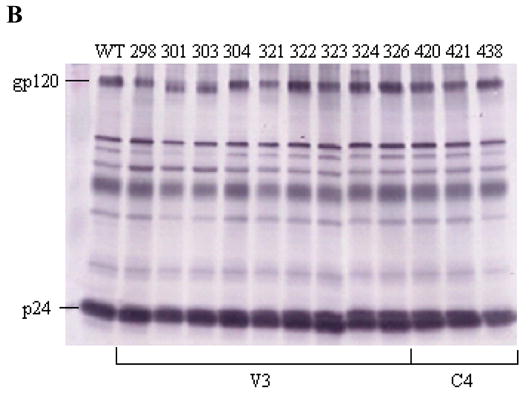

Effects of mutations on expression, processing, and virion incorporation

Since gp120 expression and virion incorporation can affect the ability of the envelope to interact with CCR5, we wanted to verify that the introduced alanine substitutions did not cause drastic changes in these gp120 properties. Fig. 3B shows a representative western blot of viral lysates for the V3 and C4 mutants that reduced cell-cell fusion by approximately 50% or more. We note that mutations N301A and T303A abolish the known canonical N-linked glycosylation site (NXT), which could account for the slight shift in electrophoretic mobility of gp120. To measure the amount of envelope glycoproteins in the viral lysates, the ratios of gp120 to p24 were determined by densitometry. Comparable ratios observed between the WT and defective mutants indicate similar levels of gp120 expression and virion incorporation. In addition, we examined the viral lysates of other mutants that retained fusogenic activity (data not shown) and found a similar range of gp120 to p24 ratios for the non-defective and defective envelopes. Taken together, we saw no evidence that gp120 expression and virion can account for the observed decrease in CCR5 usage by these mutant clones.

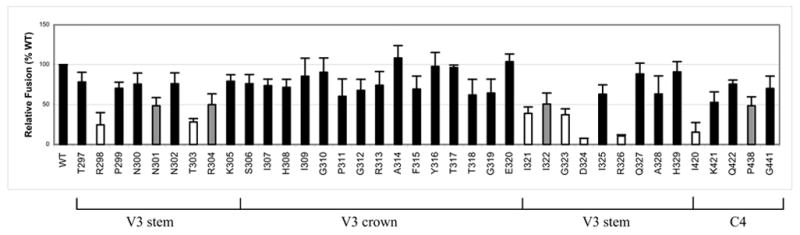

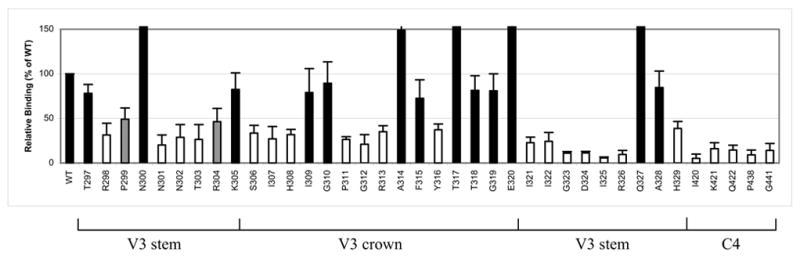

Effects of mutations on CCR5 binding

In order to identify gp120 elements that are important for CCR5 binding, soluble gp120 subunits containing V3 or C4 mutations were generated using expression vectors, and their ability to bind to cell surface CCR5 was determined. We employed a recently described quantitative cell-based ELISA method (Zhao et al., 2004), which measures the binding of soluble gp120-sCD4 complexes to Cf2th cells that express high levels of CCR5. As shown in Fig. 4, alanine substitutions of residues in both the V3 and C4 domains markedly reduced the ability of soluble gp120-sCD4 complexes to bind to CCR5-expressing cells. Eleven mutations located in the V3 stem decreased CCR5 binding by more than 50% of WT, reinforcing the role of the V3 stem in CCR5 usage. Although V3 crown residues were not critical in mediating cell-cell fusion, seven mutations in the V3 crown also reduced relative CCR5 binding levels by 50% or more. In addition, five substitutions in the V3 loop (N300A, A314G, T317A, E320A, and Q327A) were found to drastically increase CCR5 binding relative to the WT glycoprotein (223%, 149%, 415%, 444%, and 268%, respectively). In binding experiments, the role of the C4 domain in CCR5 interaction was more pronounced, as all five C4 mutations resulted in more than an 80% reduction in CCR5 binding by monomeric gp120 subunits. Taken together, these data indicate that binding of gp120 to CCR5 requires residues in both the V3 stem and crown, and is dictated by some highly conserved residues in the C4 region.

Fig. 4.

Effect of V3 and C4 mutations on CCR5 binding of soluble gp120-CD4 complexes, as measured by cell-based ELISA. Values are expressed as a percentage of WT. White bars indicate values (mean plus one standard deviation) less than 50%. Gray bars indicate mean values that are approximately 50%. Data shown represent the means and standard deviations of data from at least three independent experiments, with each experiment carried out in duplicate.

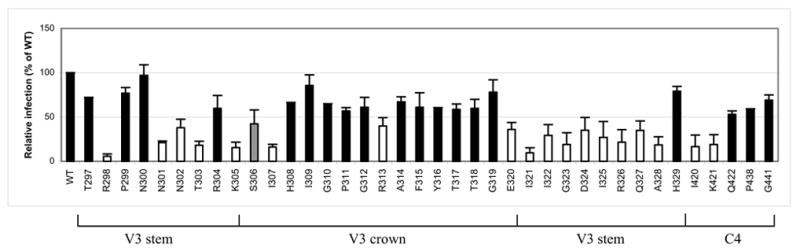

Effects of mutations on virus infection

Virus infection requires the successful completion of coreceptor binding and membrane fusion. To determine the effects of gp120 V3 and C4 mutations on CCR5-dependent HIV-1 infection, U87-CD4-CCR5 target cells were infected with virus and p24 levels were measured seven days post-infection. As shown in Fig. 5, V3 mutations that markedly reduced p24 levels by more than 50% of WT were mainly located in the N- and C-terminal ends of the V3 loop, although we note that the N307A and E320A mutations fall right at the junction between the stem and the crown. The R313A substitution in the crown that occurs right next to the GPG crest of the V3 loop also decreased infection levels by more than 50%, although the reduction was not quite as pronounced as some of the other V3 stem mutations. We also observed that only two (I420A and K421A) C4 mutations resulted in poor viral replication, as measured by more than a 50% decrease in p24 levels relative to WT.

Fig. 5.

Effect of V3 and C4 mutations on virus infection, as measured by p24 levels in virus-infected cultures at day 7. White bars indicate values (mean plus one standard deviation) less than 50%. Gray bars indicate mean values that are approximately 50%. Data shown represent the means and standard deviations of data from at least two independent experiments, with each experiment carried out in duplicate.

Comparisons of cell-cell fusion, CCR5 binding, and virus infection assays

To determine whether the CCR5 binding assay or the cell-cell fusion assay is a better indicator of CCR5 utilization, we examined whether the ability of monomeric gp120 to bind to CCR5 or the ability of the envelope glycoprotein to mediate cell-cell fusion correlated better with virus infection in CCR5-expressing cells. Upon comparing relative binding, fusion, and infection levels, we identified two groups of mutants with interesting phenotypes. The first group contained mutants that are deficient in CCR5 binding but are able to mediate fusion and infection with moderate to high efficiency. These included mainly V3 crown and C4 mutants, with the most pronounced being the V3 mutants P311A, G312A, Y316A, and H329A and the C4 mutants Q422A and G441A. The second group consisted of mutants that display dramatically enhanced binding to CCR5 with no corresponding increases in fusion and infection levels. Five V3 mutants (N300A, A314G, T317A, E320A, and Q327A) consistently showed increased binding to CCR5, between 2-4 times that of WT. Overall, using the Spearman rank correlation method with Bonferroni-adjusted significance level, we found a positive correlation between CCR5 binding and cell-cell fusion (rs = 0.7350, p < .0001). However, our data indicates that CCR5 binding by monomeric gp120 does not always predict CCR5 usage by gp120 when it is presented in its more native state, such as that used in the fusion and virus infection assays. In addition, we found a higher correlation between relative infection and fusion (rs = 0.5372, p = .0013) than between relative infection and CCR5 binding (rs = 0.4194, p = .0236).

Discussion

In this study, we systematically compared the involvement of V3 stem, crown, and C4 residues in the binding and fusion steps of gp120-CCR5 interaction using the subtype B JRFL envelope as a model system. The premise of this study was that CCR5 structures that support binding and fusion have been mapped to overlapping but distinct regions, with the Nt more important for binding and the ECLs more critical for fusion and infection (Doranz et al., 1997). It follows that gp120 domains that support binding and fusion may involve overlapping but distinct regions as well. Given that the current model for gp120-CCR5 interaction depicts the V3 stem and C4 binding to the CCR5 Nt while the V3 crown interacts with the ECL2, we hypothesized that mutations in the V3 crown could have more impact on fusion and viral entry than those in the V3 stem and C4 region. We conducted alanine-scanning of the V3 loop and five highly conserved C4 residues in the JRFL envelope and compared the effects of these substitutions on cell-cell fusion, CCR5 binding, and virus infection levels. Our results provide strong evidence, at least in the strain analyzed, that CCR5 binding does not always predict functional CCR5 usage by gp120 and indicate that mutating some V3 crown and C4 residues can have differential effects on the binding and fusion steps of gp120-CCR5 interaction. Contrary to our prediction, we found that mutations in the V3 crown had a large impact on gp120-CCR5 binding but had relatively little or no impact on fusion and virus infectivity. Instead, eight substitutions in highly conserved V3 stem residues reduced both CCR5 binding and subsequent fusion and viral entry by more than 50%.

It should be noted that using the envelope glycoprotein of ConB, Wang et al. (1999) identified three residues in the V3 crown that were also important for virus infection via CCR5. However, since mutants of ConB were not studied for cell-cell fusion or CCR5 binding, it is unclear whether the V3 crown substitutions disrupted gp120-CCR5 interaction or a post-entry step in viral replication. In fact, we also identified three mutations in the V3 crown that reduced virus infection by more than 50% in this study, but none of these mutants significantly altered fusogenicity. We note that two of these three mutations (I307A and R313A) are identical to those identified by Wang et al. (1999). Since these mutants were able to mediate cell-cell fusion but replicated poorly in CCR5-expressing cells, the possibility that the V3 mutations may affect some early post-entry step in viral replication needs to be considered.

In a previous study by Cormier et al. (2001), 16 out of 33 V3 loop residues were studied for their involvement in binding to cell-surface CCR5. In this study, we systematically analyzed all V3 residues in the stem and crown and looked at their effects on CCR5 binding as well as their functional consequences on cell-cell fusion and viral entry. We note that our results are largely in agreement with Cormier et al. (2001) among the residues that we both analyzed, with the exception of two point mutations (G310A and F315A). In the study by Cormier et al. (2001), both mutants decreased CCR5 binding by more than 50%, but these mutations were not as critical in our study. One possible explanation for this discrepancy could be differences in the sensitivities of the binding assays used, which involved different forms of CD4 and different cell lines that may express different cell-surface concentrations of CCR5.

Our finding provides functional evidence that CCR5 interaction by the V3 stem is not limited to just a few structurally defined “base” residues (positions 297–299) that form an integral portion of the gp120 core, as has been suggested by the V3 crystal structure of Huang et al. (2005). Furthermore, the crystal structure appears to suggest that the base of the V3 loop lies in close proximity to the bridging sheet, which encompasses the five C4 mutants analyzed in this study. Our data, however, raises the possibility that the structurally defined V3 “base” and C4 region may not form a unified functional entity given their different effects on binding and fusion.

Disrupting the gp120 V3 or C4 regions can lead to differences in coreceptor binding and cell-cell fusion by affecting the molecular anatomy of CCR5 utilization. Mutations that limit the functional interaction of gp120 to only one CCR5 domain may weaken the affinity of gp120 to CCR5, which can be below the threshold for detectable binding by monomeric gp120 but is sufficient for fusion to occur. Fusion assays employ oligomeric envelope proteins, so a change in affinity of individual gp120 subunits may be compensated by the overall avidity of the trimer to CCR5. In support of this, two V3 loop mutations that did not alter CCR5 usage in fusion and infection experiments were reported to reduce coreceptor binding by two-fold and affected the molecular anatomy of CCR5 utilization (Hu et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2000). From our study, it appears that there are other residues mostly in the V3 crown and C4 region that could similarly affect gp120 utilization of different CCR5 domains. To lend further support to this interpretation, future studies that examine the binding and fusion of our gp120 mutants to cells expressing CCR5 coreceptor chimeras are needed.

Alternatively, V3 or C4 mutations may enhance the efficiency or kinetics with which CCR5 binding triggers conformational changes in gp120 that lead to membrane fusion, thus allowing lower affinity envelopes to effectively utilize CCR5 for fusion events. Reeves et al. (2004) reported one C4 mutation that highly disrupted gp120-CCR5 binding but not fusion and infection. This mutant displayed increased sensitivity to the binding inhibitor TAK-779 but lower sensitivity to the fusion inhibitor T-20, which suggested lower gp120-CCR5 affinity but increased efficiency of membrane fusion. Similarly, some V3 mutations have also been shown to enhance fusogenicity, thereby decreasing viral sensitivities to T-20 and enabling the virus to use low affinity CCR5 mutants (Platt, Durnin, and Kabat, 2005; Platt et al., 2005). In light of these findings, future studies that test our envelope mutants for sensitivity to the inhibitors TAK-779 and T-20 may help further clarify the mechanism of action of the introduced substitutions.

We also noted that five mutations in the V3 stem and crown consistently resulted in dramatically enhanced binding with no corresponding increases in fusion and infection levels. Only one of these five V3 substitutions (E320A) has previously been studied, and this mutation was indeed shown to increase CCR5 binding (Cormier et al., 2001). It is possible that these V3 mutations may alter the conformation of gp120 such that it becomes more accessible to CCR5 and enhances coreceptor affinity. These residues may form close contacts with CCR5, or they may form bonds internally within gp120 that stabilize the topology of the V3 crown and stem regions. It should be emphasized, however, that these mutations appear to affect the affinity of monomeric more than trimeric envelope, since we see no corresponding increases in fusion or infection levels.

The cascade of early events in the viral life cycle starts with a virus binding to the appropriate receptors on target cells, leading to efficient membrane fusion events, viral entry, and subsequently, productive infection. In this study, new evidence is provided to support the notion that CCR5 binding assays using monomeric gp120 do not always predict CCR5 utilization by gp120 when it is presented in its trimeric form. Furthermore, we show that infection levels correlated higher with fusogenicity than with CCR5 binding, suggesting that the cell-cell fusion assay is more predictive of CCR5 usage and viral entry than the monomeric gp120 binding assay.

We recognize that HIV-1 is not a genetically homogenous family of virus and the question as to what extent our finding will be shared by other HIV-1 requires further study. It is noted that the results on cell fusion and virus infectivity are actually consistent with our previous work using a subtype C envelope (Suphaphiphat et al., 2003), thus reinforcing the relatively more important role of the V3 stem compared to the V3 crown and C4 region in overall CCR5 usage even with a genetically divergent HIV-1 strain. However, future studies that look at other HIV-1 isolates and subtypes will help determine how general these findings are to other envelopes. Our data does emphasize the importance of analyzing both coreceptor binding and cell-cell fusion since different gp120 domains may play overlapping and distinct roles in the binding and fusion steps of gp120-CCR5 interaction. The direct binding assay alone is not sufficiently robust to fully delineate HIV envelope-coreceptor interactions during viral entry.

Materials and Methods

Cells

Human kidney 293 cells and African green monkey CV-1 cells were maintained at 37ºC in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (DMEM/FBS/PS). Human glioma cell lines, U87-CD4-CCR5 and U87-CD4-CXCR4, and the canine thymocyte cell line, Cf2th/synCCR5, were obtained from the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (NIH, Bethesda, MD). U87 cells were cultured in DMEM/FBS/PS plus 1 μg/ml puromycin and 300 μg/ml genecitin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cf2Th/synCCR5 cells were maintained in DMEM/FBS/PS with 3 μg/ml puromycin, 500 μg/ml genecitin, and 500 μg/ml ZeocinTM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Construction of Chimeric and Mutant Viruses

The HIV-1 subtype B molecular clone HXB2-RU3 has previously been described (Trujillo et al., 1996). HXB2-JRFL/d2EGFP, a chimeric molecular clone containing the JRFL envelope that contains an artificially inserted BamHI site in the env region and tagged with d2EGFP, was contributed by Z. Matsuda (NIH). The 2.6-kb SalI-BamHI envelope fragment of HXB2-JRFL/d2EGFP was used to replace the corresponding env region of HXB2-RU3 to generate an HXB2-JRFL provirus that does not contain the GFP tag. To generate JRFL envelope mutant clones, the SalI-EspI envelope fragment of HXB2-JRFL was cloned into the PGEM11 vector (Promega, Madison, WI) to create the subclone PGEM-JRFL. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension PCR (Ho et al., 1989) was used to introduce single alanine substitutions to each of the V3 residues, as well as to five C4 residues. The SalI-EspI fragment of PGEM-JRFL containing the directed mutation was cloned back into HXB2-JRFL to generate the full-length proviral clones. All mutations were verified by DNA sequencing.

Construction of Soluble gp120

The 3.0-kb SalI-EspI envelope fragment of PGEM-JRFL was cloned into a p303TD expression vector (Invitrogen) to generate TD-JRFL. Using TD-JRFL as template, a stop codon (TAA) was inserted at the end of gp120 by overlap extension PCR to generate the soluble JRFL gp120 expression vector, sTD-JRFL. Soluble C4 mutant gp120 expression vectors were constructed in a similar fashion, using PGEM-JRFL clones containing the directed C4 mutation. To create soluble V3 mutant gp120 expression vectors, the SalI-Bsu36I fragment of PGEM-JRFL clones containing the desired V3 mutation was directly cloned into sTD-JRFL. To generate soluble gp120, 5 μg of sTD-JRFL and mutants were transfected into 8 × 105 293 cells using the Superfect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen, Hidden, Germany) and cell-free supernatants were collected 72 hr after transfection, and frozen at −80°C until used.

Virus Infection in U87-CD4-CCR5 Cells

Ten micrograms of proviral DNA were transfected into 1.5 × 106 293 cells using Superfect. Cell-free supernatants were collected 72 hr after transfection, passed through 0.45 μm filters (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA), and frozen at −80°C until used. The p24 concentration was determined by the HIV-1 p24 ELISA kit (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, MA). To monitor viral replication, equal amounts of viruses, standardized by 10 ng of p24, were used to infect 1 × 105 U87-CD4-CCR5 or U87-CD4-CXCR4 cells in a 24-well plate. Culture supernatants were assayed by p24 ELISA on day 7 post-infection.

β-Galactosidase Reporter Gene Activation Assay to Measure Cell Fusion

Fusion was analyzed by modification of a previously described reporter gene activation assay (Nussbaum, Broder, and Berger, 1994). 8 × 104 293 cells on 96-well microtiter plates were transfected with 0.5 μg proviral DNA using Superfect. After 48 hr, the cells were infected with the recombinant vaccinia-virus vCB21R-lacZ (MOI 10; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program) containing the E. Coli lacZ gene linked to a bacteriophage T7 promoter. A second population of cells, U87-CD4-CCR5, was infected with the recombinant vaccinia-virus vTF7-3 (MOI 10; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program), which expresses T7 RNA polymerase under the control of the natural P7.5 early-late vaccinia virus promoter. After 1.5 hr, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated overnight. U87-CD4-CCR5 cells were scraped, and 8 × 104 cells were added to the 293 cells. Fusion was allowed to proceed for 6 hr, after which cells were lysed by the addition of Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega). β-Gal activity in cell lysates was assayed using the β-Gal Assay Kit (Invitrogen). The value for cell fusion (based on β-Gal activity) was calculated with the formula:

Western Blot Analysis of Cell and Viral Lysates

Ten micrograms of proviral DNA were transfected into 1.5 × 106 293 cells using Superfect. Cell and viral lysates were prepared as described (Wang et al., 1999) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. A reference pooled HIV-1 subtype B positive serum (1:400 dilution) was used for Western blot analysis.

ELISA for gp120-sCD4 Binding

Soluble CD4 (sCD4) was obtained by infecting CV-1 cells with the recombinant vaccinia virus vCB5, a sCD4-expression vector (MOI 40; NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program), for 3 hr. Following overnight incubation, cell-free supernatants were collected and treated with 1% Triton-X for 30 min at 4°C. Gp120 was generated by transfecting 293 cells with 10 μg of proviral DNA and harvesting cell lysates 72 hr after transfection. The amount of gp120 in the cell lysates was determined by ELISA. Sheep polyclonal antibody (Ab) D7324 to the conserved C-terminal 15 amino acids of HIV-1 gp120 (NIH AIDS Research And Reference Reagent Program) was used as capture Ab, and pooled HIV-1 subtype B human serum was used as detection Ab. Bound Ab was detected using alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated goat anti-human Ig and the AMPAK system (Dako, Cambridgeshire, UK). Binding of gp120 to sCD4 was carried out as previously described (Moore, 1990), with several modifications. Gp120 in cell lysates was incubated in wells coated with 2 μg/ml D7324. Equal amounts of supernatant containing sCD4 were added to the wells, and bound sCD4 was detected using T4-4, a rabbit polyclonal Ab against CD4 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program). The concentration of sCD4 used displayed about half-maximal binding to captured gp120. AP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was used as secondary Ab and was detected using the AMPAK system. A490 was monitored with a microtiter plate absorbance reader. The value for sCD4 binding, normalized for the amount of gp120 in the cell lysate, was calculated with the formula:

Cell-Based ELISA for CCR5 Binding

CCR5 binding assays were carried out as previously described (Zhao et al., 2004), with the following modifications. 5 × 104 Cf2th/synCCR5 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and cultured at 37°C overnight. Cells were fixed with 5% formaldehyde in 0.01 M PBS for 5 min at RT. The plates were washed three times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 0.01 M PBS at 4°C overnight. Soluble gp120-sCD4 complexes, formed by incubating 200 μl soluble gp120-containing supernatants with 1 μg sCD4 (Protein Sciences, Meriden, CT) for 1 hr at RT with gentle shaking, were added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 hr. Bound complexes were detected using M-T441, a mouse Ab that recognizes the D2 domain of CD4 (Ancell, Bayport, MN), followed by AP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG as secondary antibody. The amount of soluble gp120 in the supernatant was also determined by ELISA, as described above for determining the amount of gp120 in cell lysates. The amount of bound gp120-sCD4 complex, normalized for the amount of soluble gp120 in the supernatant, was calculated using the following formula:

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank M.F. McLane for viral propagation. P.S. was supported by grant TW00004 from the Fogarty International Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chen B, Vogan EM, Gong H, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Harrison SC. Structure of an unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 core. Nature. 2005;433(7028):834–41. doi: 10.1038/nature03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier EG, Dragic T. The Crown and Stem of the V3 Loop Play Distinct Roles in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Envelope Glycoprotein. Interactions with the CCR5 Coreceptor. J Virol. 2002;76(17):8953–8957. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8953-8957.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormier EG, Tran DN, Yukhayeva L, Olson WC, Dragic T. Mapping the determinants of the CCR5 amino-terminal sulfopeptide interaction with soluble human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120-CD4 complexes. J Virol. 2001;75(12):5541–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5541-5549.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doranz BJ, Lu ZH, Rucker J, Zhang TY, Sharron M, Cen YH, Wang ZX, Guo HH, Du JG, Accavitti MA, Doms RW, Peiper SC. Two distinct CCR5 domains can mediate coreceptor usage by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71(9):6305–14. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6305-6314.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Genetics. 1989;77(1):51–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Napier KB, Trent JO, Wang Z, Taylor S, Griffin GE, Peiper SC, Shattock RJ. Restricted variable residues in the C-terminal segment of HIV-1 V3 loop regulate the molecular anatomy of CCR5 utilization. J Mol Biol. 2005;350(4):699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Trent JO, Tomaras GD, Wang Z, Murray JL, Conolly SM, Navenot JM, Barry AP, Greenberg ML, Peiper SC. Identification of ENV determinants in V3 that influence the molecular anatomy of CCR5 utilization. J Mol Biol. 2000;302(2):359–75. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CC, Tang M, Zhang MY, Majeed S, Montabana E, Stanfield RL, Dimitrov DS, Korber B, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt R, Kwong PD. Structure of a V3-containing HIV-1 gp120 core. Science. 2005;310(5750):1025–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1118398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393(6686):648–59. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JP. Simple methods for monitoring HIV-1 and HIV-2 gp120 binding to soluble CD4 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: HIV-2 has a 25-fold lower affinity than HIV-1 for soluble CD4. AIDS. 1990;4(4):297–305. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199004000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum O, Broder CC, Berger EA. Fusogenic mechanisms of enveloped-virus glycoproteins analyzed by a novel recombinant vaccinia virus-based assay quantitating cell fusion-dependent reporter gene activation. J Virol. 1994;68(9):5411–22. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5411-5422.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt EJ, Durnin JP, Kabat D. Kinetic factors control efficiencies of cell entry, efficacies of entry inhibitors, and mechanisms of adaptation of human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2005;79(7):4347–4356. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4347-4356.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt EJ, Shea DM, Rose PP, Kabat D. Variants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that efficiently use CCR5 lacking the tyrosine-sulfated amino terminus have adaptive mutations in gp120, including loss of a functional N-glycan. J Virol. 2005;79(7):4357–4368. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4357-4368.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves JD, Miamidian JL, Biscone MJ, Lee FH, Ahmad N, Pierson TC, Doms RW. Impact of mutations in the coreceptor binding site on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fusion, infection, and entry inhibitor sensitivity. J Virol. 2004;78(10):5476–5485. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5476-5485.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto C, Sodroski J. Fine definition of a conserved CCR5-binding region on the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein 120. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16(8):741–9. doi: 10.1089/088922200308747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuto CD, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong PD, Hendrickson WA, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280(5371):1949–53. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suphaphiphat P, Thitithanyanont A, Paca-Uccaralertkun S, Essex M, Lee TH. Effect of amino acid substitution of the V3 and bridging sheet residues in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C gp120 on CCR5 utilization. J Virol. 2003;77(6):3832–7. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.6.3832-3837.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, Binley JM, Olson WC, Allaway GP, Cheng-Mayer C, Robinson J, Maddon PJ, Moore JP. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its co-receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384(6605):184–7. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo JR, Wang WK, Lee TH, Essex M. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as a determinant of a CD4-negative neuronal cell tropism for HIV-1. Virology. 1996;217(2):613–7. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WK, Dudek T, Essex M, Lee TH. Hypervariable region 3 residues of HIV type 1 gp120 involved in CCR5 coreceptor utilization: therapeutic and prophylactic, implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(8):4558–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WK, Dudek T, Zhao YJ, Brumblay H, Essex M, Lee TH. CCR5 co-receptor utilization involves a highly conserved arginine residue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5740–5745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss CD. HIV-1 gp41: mediator of fusion and target for inhibition. AIDS Rev. 2003;5(4):214–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Gerard NP, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso AA, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384(6605):179–83. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt R, Sullivan N, Thali M, Repke H, Ho D, Robinson J, Posner M, Sodroski J. Functional and immunologic characterization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins containing deletions of the major variable regions. J Virol. 1993;67(8):4557–65. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4557-4565.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Lu H, Schols D, De Clercq E, Jiang S. Development of a cell-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for high-throughput screening of HIV type 1 entry inhibitors targeting the coreceptor CXCR4. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;19(11):947–55. doi: 10.1089/088922203322588297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]