Abstract

The adult clinical necropsy has been declining for many years and is nearing extinction in many hospitals. In Norwich, to prevent this from occurring, a Pathology Liaison Nurse (PLN) was appointed, resulting in a modest reversal of the trend. In 2005, the number of adult clinical necropsies increased to 58 (clinical necropsy rate = 2.4%) from its nadir of 34 (clinical necropsy rate = 1.4%) in 2003. Moreover, consent is now much more likely to be full and to allow histopathological and other studies. The PLN ensures that consent is properly and fully obtained, in line with current legislation. She also plays an important role in arranging for feedback to be given by clinicians to the families after the examination, and in teaching and training Trust staff about death, bereavement, and related matters. This paper describes how the role of PLN was established and evaluated, and gives details of the current state of the adult clinical necropsy in Norwich.

Keywords: clinical autopsy, rate, decline, pathology liaison nurse

It has been suggested both that error is an immutable component of medical practice1 and that the high‐quality necropsy remains a paramount benchmark of a high‐quality healthcare system.2 Indeed, a high necropsy rate can be associated with a significant decline in the frequency of major diagnostic errors.3 Necropsies provide a source of knowledge for future application, adding data on the local epidemiology of disease and on the quality control of investigations.3 Moreover, the greater understanding of a patient's illness following necropsy may also benefit the family.4 However, despite these and other advantages, the clinical (consented) necropsy has been declining for many years, both in the United Kingdom5,6,7,8 and in other countries.9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 Such is its state of decline that it is in danger of dying out completely.18 In the USA, some hospitals have converted their necropsy facilities into space for other purposes. and new hospitals are being built without necropsy rooms.19

During 1996–2003 Norwich followed the general trend, with the reduction of adult clinical necropsies being approximately linear.20 While the publicity surrounding events in Bristol and at the Alder Hey Hospital seemed not to alter the rate of decline of the adult clinical necropsy, we noticed a detrimental effect on the extent of examination permitted by families. There were substantial effects on both the clinical necropsy rate and the extent of examination in perinates and neonates.20

We wished to reverse the decline in adult clinical necropsies, not only for the reasons noted above but also because of the needs of the newly established medical school based at the University of East Anglia21 and to assist in training our histopathology senior house officers and specialist registrars. We thought that the demand on clinicians' time in completing the documentation for necropsy was one factor in the decline in the clinical necropsy rate. Consent for necropsy using our old one‐page form normally took 20–30 min to complete. With the new national consent forms, which we started to use as a pilot study for the Department of Health in Spring 2002, it usually takes 30–60 min. Moreover, many clinicians are not properly trained in obtaining consent for necropsy,20 raising questions about its quality.

In order to reduce the demands on clinicians' time and to ensure that consent for necropsy is properly informed and elicited, the Trust agreed to establish a 0.6 whole‐time‐equivalent post of Pathology Liaison Nurse (PLN). This paper describes how we established and developed that post, and the current state of the adult clinical necropsy in Norwich.

Establishing the role of Pathology Liaison Nurse

In establishing the post, initially for a trial period of one year, the Trust sought to ensure that clinicians were relieved of the burden of requesting clinical necropsies and that the request and related discussion were empathetic and to a consistently high standard. The PLN would be readily accessible to the families of recently deceased patients and ensure that their wishes about the extent of the necropsy and the retention and subsequent disposal of samples were properly carried out. The PLN would be somebody to whom the family could refer with questions about the examination and its aftermath, including obtaining information about the findings. The post was advertised for a Registered Graduate Nurse with at least five years' work at grade E and experience of working and communicating with bereaved families. One candidate (EL) was interviewed and appointed, taking up the post on 1 February 2004. She was experienced in working with the bereaved, initially as a clinical nurse and in later years as a bereavement counsellor in the voluntary sector. In addition, she was an experienced trainer within the Trust, delivering multidisciplinary courses, including those on bereavement. The funding for the post during the trial period was obtained from Trust endowment funds.

During her first week in post, the PLN underwent a comprehensive induction to the mortuary service, including attending necropsies. This provided personal experience, which would inform her discussions with bereaved families. She spent time with the staff in the mortuary, seeing all aspects of their work, and was shown how samples are retained for histopathological diagnosis and the processes involved in converting such material into stained sections. During this time, she received training in the ethical and legal issues surrounding necropsy, read widely around the subject, and reviewed the Trust's documentation.

The PLN also attended meetings between clinicians and bereaved families, where the issue of consent for necropsy was discussed. She soon became confident in eliciting such consent herself and in liaising with clinicians, pathologists and the bereavement service, to which she is also attached. Following the issuing of a protocol (Trust protocol for registered nurses to obtain consent for postmortem examination on an adult, April 2004), of which she was a co‐author, she has undertaken the consenting for almost all adult clinical necropsies. Clinicians decide how much of the process they wish to undertake themselves but almost all are happy to delegate this task to the PLN.

During the trial, the PLN reported to one of the consultant histopathologists (RYB) and was accountable to the Director of Nursing and Education.

Evaluation of the post

The PLN post was formally evaluated near the end of the trial year. The opinions of consultants who had used the service were sought, and a small survey of some of those family members who had given permission for necropsy was undertaken. The informal opinions of the consultant histopathologists were also obtained.

Opinion of clinical consultants during trial period

A questionnaire was sent to consultants whose teams had requested a clinical necropsy since the PLN was appointed. The questions were phrased as a mixture of positive and negative statements, and responders were asked to indicate whether they agreed (either strongly or ordinarily), disagreed (either strongly or ordinarily), or had no opinion on the matter. Respondents could also provide free‐text comments. Sixteen questionnaires were sent, and 12 replies were received. Of these, four consultants said that they had had no direct contact with the PLN and could not comment. Eight respondents provided useful opinions (table 1).

Table 1 Consultant questionnaire about the role of the Pathology Liaison Nurse.

| The Pathology Liaison Nurse: | Strongly agree | Agree | No opinion | Disagree | Strongly disagree | No answer given |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust matters | ||||||

| Provides a valuable service to the Trust | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Does not improve the quality of PM* consent obtained | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Is a role which is necessary at this Trust | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Should not be retained by the Trust | 1 | 2 | 5 | |||

| Provides a valuable link to the Pathology Department | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Is of little use at this Trust | 2 | 5 | 1 | |||

| Matters to do with me and my juniors | ||||||

| Saves medical staff time | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Makes no difference to me or my junior doctors | 2 | 6 | ||||

| Does not relate well to me or my staff | 1† | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Has an appropriately professional manner | 4 | 3 | 1† | |||

| Complicates my relationship with the family | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Understands the issues behind my request for a PM* | 3 | 4 | 1 | |||

| Is an important link with the family of the deceased | 5 | 3 | ||||

| Speeds up the process of obtaining PM* consent | 5 | 3 | ||||

| Matters to do with the family | ||||||

| Has been praised by family/friends of the deceased | 1 | 6 | 1 | |||

| Has been criticised by family/friends of the deceased | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Is always sympathetic when dealing with family/friends | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| Has a professional manner | 4 | 3 | 1 | |||

| Does not relate well to members of the family | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Has time to discuss the issues with the family | 4 | 2 | 2 | |||

*PM, postmortem examination (necropsy).

†One consultant said, “Haven't met her yet!”.

This small survey suggested that the PLN provided a valuable service, which saved clinical time. One consultant noted: “The Liaison Nurse fulfils a role that junior (and senior) doctors do very badly. There must be no question of not retaining this post: to do otherwise will jeopardise the excellent service we have now come to expect”. Another wrote: “The PLN has kept me updated constantly with regards to PM [necropsy] process and liaison with family, which saves a lot of administration time and distress to the family”. No adverse comments were received.

Opinion of consenting family members

The service to those who had given permission for necropsy was assessed by an anonymous postal survey, developed in association with the Trust's Quality and Clinical Audit Department. During the later part of the trial year, the PLN asked family members who had just agreed to a necropsy whether they would allow the Trust to send them a questionnaire about the quality of the service they had received. Questionnaires were dispatched several weeks after the necropsy, to allow time for family feedback and for the immediate effects of the death to settle.

The first part of the questionnaire sought some factual information, including when the matter of necropsy was first raised and by whom, and who had completed the consent form with the relative. The respondent's opinion about the quality of consenting process was then elicited. Each assessment was given on a 6‐point scale, with the best outcome scored as 6 and the worst, its polar opposite, marked as 1. For example, the first such question was:

Using a scale of 1–6, please indicate your feelings on the initial approach regarding the postmortem of your friend/relative

Unhelpful 1 … 2 … 3 … 4 … 5 … 6 Helpful.

These questions were followed by questions about their reasons for agreeing to necropsy and about the feedback they received afterwards. At the end was a space for free‐text comments.

Near the end of the trial period, six questionnaires were sent with a covering letter and stamped addressed envelope to those who had agreed. Four responses were received. They indicated that the respondents were satisfied with the quality of the consenting process, regarding it as professional, sympathetic, sensitive and tactful. The verbal and written information about necropsy was generally considered to be easy to understand, suitable and sufficient. No written comments about the PLN were received. Free‐text comments were restricted mainly to criticism of the timeliness of the feedback received from the clinicians, an important matter that is beyond the scope of this paper.

Developing the role of PLN after the trial year

The Trust Board accepted the recommendation that the post of PLN should be made substantive and its management rationalised. The PLN now reports to the Deputy Director of Nursing. She liaises closely with a consultant histopathologist (RYB) in developing the role, and with the consultant histopathologists on necropsy duty for day‐to‐day issues. Funding was provided from the normal staff budget.

The PLN now also assists in the training of medical students, junior doctors and ward nursing staff in issues related to death, including necropsy. She has also been involved in the training and appointment of two deputies to cover her duties during periods of absence. In discussion with HM Coroner for Norwich and Central Norfolk, her role has extended to include obtaining consent from the next‐of‐kin for the retention of material for academic interest from his cases. As such consent is requested at the time of necropsy, it is elicited by telephone, using a special protocol and record sheet. Signed written consent is obtained later.

The post continues to be evaluated. The survey of the next‐of‐kin has continued since the trial year and provides data for regular audit. Since the trial, 18 more questionnaires have been sent, with 12 replies received. Feedback from families continues to be favourable (table 2).

Table 2 Family questionnaire about their reaction to the request for necropsy.

| No* | Mean (median) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Using a scale of 1–6, please indicate your feelings on the initial approach regarding the postmortem of your friend/relative | |||

| Unhelpful → helpful | 16 | 5.8 (6) | 5–6 |

| Inconsiderate → considerate | 15 | 5.5 (6) | 4–6 |

| Tactless → tactful | 15 | 5.5 (6) | 4–6 |

| At the time you were approached regarding the postmortem of your friend/relative, how would you rate (using the same rating scale) the verbal information given to you? | |||

| Insufficient → sufficient | 15 | 5.6 (6) | 5–6 |

| Not very easy to understand → easy to understand | 15 | 5.7 (6) | 5–6 |

| Unsuitable → suitable | 14 | 5.6 (6) | 5–6 |

| At the time you were approached regarding the postmortem of your friend/relative, how would you rate (using the same rating scale) the written information given to you? | |||

| Insufficient → sufficient | 14† | 5.7 (6) | 4–6 |

| Not very easy to understand → easy to understand | 14† | 5.7 (6) | 4–6 |

| Unsuitable → suitable | 14† | 5.5 (6) | 4–6 |

| Were your questions answered to your satisfaction? (Please use the same rating scale) | |||

| Unsatisfactory → very satisfactory | 16 | 5.9 (6) | 5–6 |

| Overall, do you consider your experience of being asked for consent to a postmortem examination was dealt with: (please use the same rating scale) | |||

| Unprofessionally → professionally | 15 | 5.7 (6) | 4–6 |

| Unsympathetically → sympathetically | 14 | 5.7 (6) | 5–6 |

| Not at all understanding → in an understanding way | 14 | 5.6 (6) | 4–6 |

| Insensitively → sensitively | 15 | 5.5 (6) | 4–6 |

| Tactlessly → tactfully | 14 | 5.5 (6) | 4–6 |

*The data are amalgamated from the trial year survey and subsequent questionnaires. Altogether, 16 replies were received. Not all questions were answered.

†One person did not receive any written information.

The clinical necropsy rate and the extent of PM allowed are also regularly assessed.

Review of the numbers and extent of adult clinical necropsies

The number of adults dying in Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital during the period 1 January 1996 to 31 December 2005, the number undergoing clinical necropsy, and the extent of the examination permitted were determined from the records of the mortuary and of the Department of Histopathology. We then calculated the clinical necropsy rate (number of clinical necropsies divided by the number of deaths, expressed as a percentage). Coroners' necropsies were excluded.

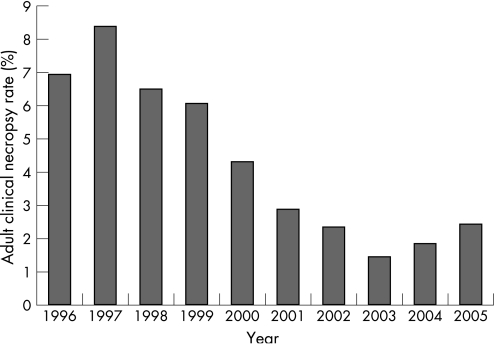

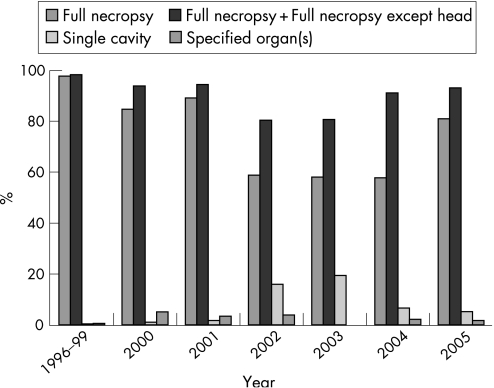

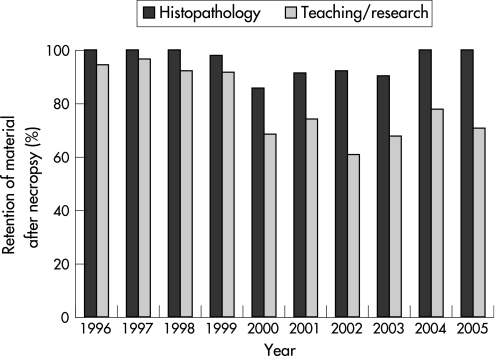

The decline in the number of adult clinical necropsies undertaken during 1996–2003 was reversed during 2004–05 (fig 1). In 1997, 167 adult clinical necropsies were undertaken (clinical necropsy rate 8.4%), but there were only 34 in 2003 (clinical necropsy rate 1.4%), a reduction of nearly 80%. During 2004, 45 adult clinical necropsies were undertaken (clinical necropsy rate 1.8%). Further improvement occurred in 2005, with 58 adult clinical necropsies (clinical necropsy rate 2.4%). During the last two years, there has also been an improvement in the extent of examination permitted during adult clinical necropsy (fig 2) and in the retention of material afterwards for histopathological examination (100% in both years) and teaching or research (fig 3). Most necropsies during 2004 and 2005 were full examinations (58% and 81%, respectively) or full examinations except the head (33% and 12%, respectively). Few during 2004 and 2005 specified a single body cavity (4.4% and 7.4%, respectively) or individual organ(s) (2.2% and 1.7%, respectively).

Figure 1 The adult clinical necropsy rate in Norwich during the last 10 years.

Figure 2 Extent of necropsy permitted. The total number of necropsies assessed for each period was 470 (1996–99), 98 (2000), 58 (2001), 51 (2002), 31 (2003), 45 (2004) and 58 (2005).

Figure 3 Permission for retention of material for histopathological examination and for teaching and research.

Discussion

During 1996–2003 there was an approximately linear decline in the adult clinical necropsy rate in Norwich, reaching a nadir of 1.4% in 2003. This decline was reversed in 2004 and 2005, coinciding with the appointment of the PLN and the associated internal publicity to promote both her role and the value of the clinical necropsy. A similar reversal in the decline of the hospital necropsy rate, but starting from a higher level, has been achieved at the Yale University School of Medicine following the introduction of a quality‐improvement programme.15 Our improvement in adult clinical necropsy rate, to 2.4% in 2005, is modest in comparison to that achieved at Yale15 or in Queensland22 and remains far short of the recommendations of the Royal Colleges of Pathologists, Physicians and Surgeons23 and others.24 The royal colleges' joint working party did not specify a standard necropsy rate but suggested a minimum random sample of 10% of adult deaths for audit purposes, noting that an overall rate of 35% had been suggested as adequate.23 Britton's strategy suggested a random 20% sample of deaths.24

It is unlikely that such high rates could be sustained in the United Kingdom today, as the resources required would be far greater than most departments could provide. It is important that necropsies are performed properly,25 but that is time‐consuming, and the reporting of biopsies and resection specimens, which usually takes precedence, has become more complex, demanding more of the histopathologist's time.14,26 Pathologists themselves may have contributed to the decline in clinical necropsies,27 which often have a lowly status in pathology departments,28 partly because of poor technique as a result of inadequate training in the discipline10,28 and partly by the delay in communicating their findings to clinicians.7,13,14,15,28 The recent report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death (NCEPOD)29 raised questions about the quality of coroners' necropsy reports, 26% being judged to be poor or unacceptable. It is likely that a review of reports of clinical (consented) necropsies would raise similar concerns. If necropsies are to be used as a clinical investigation, clinicians and the public must have faith in their quality. The profession (or parts of it) clearly has much to do to improve its standards in necropsy work. Interestingly, the recent NCEPOD report stated that specialist registrars and other trainees produced some excellent reports, which were generally better than those of consultant histopathologists and forensic pathologists.29 The report makes a series of recommendations for improving (coroners') necropsy reports: regular audits and other continuing professional development activities; further subspecialisation; more histopathological assessment; and practising to a defined set of quality standards, such as those produced by the Royal College of Pathologists.29 This will have significant resource implications, which would also apply to the clinical necropsy service.

It is important that we take steps to improve the clinical necropsy rate beyond the current low levels, particularly for clinical audit,9,19,23,25,30,31 for teaching and training7,23,32 and for continuing professional development.33 Indeed, it is arguable that society cannot afford not to provide the necessary resources.2 Necropsies provide an important opportunity for learning from the inevitable uncertainties (“necessary fallibility”) of medical practice, appreciating that error is inevitable and is occasionally avoidable.1,14 Necropsies also allow the description of new diseases and a greater appreciation of pathogenetic mechanisms, and are important in the development and interpretation of new imaging methods and in understanding the effects and complications of medical intervention.3,33,34,35 A modest number of targeted, well‐conducted necropsies (which should include histopathological study35) with attendance by the clinicians, allowing clinicopathological correlation, may be more effective than undertaking larger numbers of necropsies without clinical input.26 Improving the quality of necropsies by attention to the training of pathologists is also an important factor in any attempt to resurrect the clinical necropsy.10

Important factors in increasing the clinical necropsy rate are likely to include the attitude of clinicians2,5,27,36 and their satisfaction with the quality of the service they receive.15 Clinicians with a high pre‐existing interest in necropsies are more likely to request them when presented with a set of questionnaires based on hypothetical clinical scenarios than are those whose interest is low.36 The strength of a doctor's recommendation to undertake a necropsy is very significantly correlated with whether one is undertaken.2,16 If clinicians value this final investigation and have a policy of seeking a necropsy, an improved and high clinical necropsy rate can be achieved.37,38 Different interventions are effective in increasing the clinical necropsy rate. Involvement of the attending clinician in seeking consent and review of necropsy status by the head of department at the morning report was associated with a doubling of the necropsy rate in Switzerland (from 16–17% to 30–36%) in the late 1990s.38 In Cambridge, the involvement of a Patient Affairs Officer, whose role seems analogous to that of our PLN, was associated with a clinical necropsy rate of approximately 50%, which compared with a rate of about 22–28%, when junior doctors undertook consenting for necropsy.37 Her greater success was achieved by a higher request rate; the rates of refusal (30–39%) by relatives were similar when she or junior doctors undertook the request for necropsy.37 These observations were made before the events at Bristol and Alder Hey, and we do not know whether the current climate would make a difference.

In our experience, about two‐thirds of families agree to necropsy, when asked by the PLN. She depends on clinicians to ask her to obtain consent for necropsy: she does not initiate the request. The upturn in our adult clinical necropsy rate may be attributed, at least in part, to the PLN's making obtaining consent easier and less time‐consuming for them. Publicity of the importance of the clinical necropsy within the Trust may also have helped. As well as general notification (for example, to the consultant staff committee and by way of the Trust's house magazine), we have given special presentations to various clinical staff groups. This needs to continue, with more targeted publicity and the development of joint audit projects. In time, such an approach could be linked with neighbouring or regional trusts. Particular clinical audit issues could be addressed across several trusts in order to accrue sufficient data to allow meaningful analysis, including the determination of specificity and sensitivity rates for specific diagnoses.25 It has been suggested that in the USA a revival of the necropsy would be most cost‐effective if undertaken at university teaching hospitals, which would service networks of hospitals.14 Videoconferencing and other modern technologies would allow clinicopathological conferences, teaching during the necropsy, and morbidity and mortality meetings. Moreover, uniform databases could be established for collecting public health data.

As well as an improving adult clinical necropsy rate in Norwich, there are now far fewer restrictions placed on the necropsy by consenting families than there had been during 2000–03. This is welcome, as some of the restrictions in the last few years called into question the value of undertaking the investigation.

The appointment of the PLN has had many advantages. First and most important, because of her training and background, and because she has sufficient time, the process of discussing necropsy with families is thorough, empathetic and unhurried. Families have sufficient time to discuss the issues involved and to reflect on them before reaching a decision. Consent is, therefore, likely to be better informed than might otherwise have been the case. Moreover, decisions about restricting the necropsy, undertaking histopathological examination, the retention of tissues and organs for teaching and/or research, and the disposal of any retained material are all elicited and properly recorded. This reduces the likelihood of error and the risk of seriously upsetting the family and adverse publicity for the Trust. Second, the PLN is a named point of contact for the families, the clinical teams and the histopathologists. If there are any issues to be addressed, she is well placed to do so. Third, she monitors the events after necropsy and ensures that reports and ancillary investigations are completed in an acceptable timescale, allowing feedback to be available to the families as soon as is practicable. Fourth, her expertise is available for teaching and training other staff groups, particularly nurses, medical students and junior doctors, and for providing advice in other forums.

Our surveys of families after necropsy have shown that they value her role. Some respondents have written personal comments, which have tended to be highly complimentary of the service provided by the PLN. There have also been some critical notes, for example about the relatively long time it took to receive feedback from some clinical firms and about the décor in the room that is used for eliciting consent for necropsy. Such feedback is valuable, as it directs our attention to deficiencies in the service as perceived by those who use it.

The longstanding decline of the adult clinical necropsy suggests that any significant reversal will be difficult to achieve.27 Our efforts over the last two years have shown that it is possible to increase the numbers of adult clinical necropsies, reversing the trend. This has required hard work, and there is still scope for improvement. Improving clinicians' perceptions of the value of clinical necropsies, particularly in clinical audit and continuing professional development, is likely to be important.36 Medical students and junior doctors should be educated in the value of the necropsy.39 Further increases in the adult necropsy rate may require new approaches, including the automatic initiation of requesting them according to clinical diagnosis (as part of a rolling audit programme) or by those not directly involved in patient care (for example, the PLN or consultant histopathologists). Such radical changes would require careful discussion with clinical colleagues.

Our modest achievement in Norwich shows that the death of the adult clinical necropsy need not be inevitable, if the profession is prepared to act, and provides a platform for further improvement.

Take‐home messages

The decline of the adult clinical necropsy has been reversed in Norwich over the last two years.

This has coincided with the appointment of a Pathology Liaison Nurse, who discusses necropsy requests with families and obtains their consent.

The Pathology Liaison Nurse saves the clinicians time, and they value her work.

Those consenting to clinical necropsy also value the work of the Pathology Liaison Nurse, who acts as their advocate and as an intermediary between them and medical staff after the patient's death.

The Pathology Liaison Nurse's role is evolving to include education and training and liaison with HM Coroner.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to our clinical colleagues and, particularly, to the families of patients who have undergone postmortem examinations for taking part in the surveys, to Lynn Taylor and Jeanne Thurgill from the Quality and Clinical Audit Department for their help with the families' questionnaires, and to Michelle Colman and her colleagues in the mortuary for their assistance in training the PLN and for providing information about hospital deaths and adult necropsies.

Abbreviations

PLN - Pathology Liaison Nurse

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

References

- 1.Anderson R E, Fox R C, Hill R B. Medical uncertainty and the autopsy: occult benefits for students. Hum Pathol 199021128–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McManus B M, Wood S M. The autopsy. Simple thoughts about the public needs and how to address them. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;106(Suppl 1)S11–S14. [PubMed]

- 3.Sonderegger‐Iseli K, Burger S, Muntwyler J.et al Diagnostic errors in three medical eras: a necropsy study. Lancet 20003552027–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPhee S J, Bottles K, Lo B.et al To redeem them from death. Reactions of family members to autopsy. Am J Med 198680665–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldron H A, Vickerstaff L. Necropsy rates in the United Birmingham Hospitals. BMJ 19752326–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Start R D, McCullough T A, Benbow E W.et al Clinical necropsy rates during the 1980s: the continued decline. J Pathol 199317163–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Loughrey M B, McCluggage W G, Toner P G. The declining autopsy rate and clinicians' attitudes. Ulster Med J 20006983–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burton J L, Underwood J C E. Necropsy practice after the “organ retention scandal”: requests, performance, and tissue retention. J Clin Pathol 200356537–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veress B, Alafuzoff I. Clinical diagnostic accuracy audited by autopsy in a university hospital in two eras. Qual Assur Health Care 19935281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasson J, Schneiderman H. Autopsy training programs. To right a wrong. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1995119289–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindström P, Janzon L, Sternby N H. Declining autopsy rate in Sweden: a study of causes and consequences in Malmö, Sweden. J Int Med 1997242157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baron J H. Clinical diagnosis and the function of necropsy. J R Soc Med 200093463–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chariot P, Witt K, Pautot V.et al Declining autopsy rate in a French hospital. Physicians' attitudes to the autopsy and use of autopsy material in research publications. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000124739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasson J. The autopsy and medical fallibility: a historical perspective. Conn Med 200165283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sinard J H, Blood D J. Quality improvement on an academic autopsy service. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001125237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burton E C, Phillips R S, Covinsky K E.et al The relation of the autopsy to physicians' beliefs and recommendations regarding autopsy. Am J Med 2004117255–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies D J, Graves D J, Landgren A J.et al The decline of the hospital autopsy: a safety and quality issue for healthcare in Australia. Med J Aust 2004180281–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott K W M. Is the autopsy dead? ACP News Winter 200219–21.

- 19.Burton E C. The autopsy: a professional responsibility in assuring quality of care. Am L Med Quality 20021756–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carr U, Bowker L, Ball R Y. The slow death of the clinical post‐mortem examination: implications for clinical audit, diagnostics and medical education. Clin Med 20044417–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilkinson M J, Ball R Y. Teaching pathology in a new course in a new medical school: where's the fun in that? Bull Royal Coll Pathol . 2003;(124)15–17.

- 22.Ward H E, Clarke B E, Zimmerman P V.et al The decline in hospital autopsy rates in 2001. Med J Aust 200217691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slavin G, Kirkham N, Underwood J C E.et alThe autopsy and audit. Report of the Joint Working Party of the Royal College of Pathologists, the Royal College of Physicians of London and the Royal College of Surgeons of England. London: The Royal College of Pathologists, 1991

- 24.Britton M. The role of autopsies in medical audit: examples from a department of medicine. Qual Assur Health Care 19935287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill R B, Anderson R E. An autopsy‐based quality assessment program for improvement of diagnostic accuracy. Qual Assur Health Care 19935351–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall P A. Do we really need a higher necropsy rate? Lancet 19993942004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Start R D, Cotton, DWK The meta‐autopsy: changing techniques and attitudes towards the autopsy. Qual Assur Health Care 19935325–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byard R W. Who's killing the autopsy? A new tool for assessing the causes of falling autopsy rates. Med J Aust 2005183654–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas S B, Cooper H, Emmett S.et alNational Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. The coroner's autopsy: do we deserve better? London: NCEPOD 2006

- 30.Shojania K G, Burton E C, McDonald K M.et al Changes in rates of autopsy‐detected diagnostic errors over time. A systematic review. JAMA 20032892849–2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferguson R P, Burkhardt L, Hennawi G.et al Consecutive autopsies on an internal medicine service. South Med J 200497335–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galloway M. The role of the autopsy in medical education. Hosp Med 199960756–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berthrong M. The autopsy as a vehicle for the lifetime education of pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1984108506–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlietstra R E. Keeping the autopsy alive. Clin Cardiol 200427541–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roulson J, Benbow E W, Hasleton P S. Discrepancies between clinical and autopsy diagnosis and the value of post mortem histology; a meta‐analysis and review. Histopathology 200547551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Start R D, Hector‐Taylor M J, Cotton D W K.et al Factors which influence necropsy requests: a psychological approach. J Clin Pathol 199245254–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamal I S, Forsyth D R, Jones J R. Does it matter who requests necropsies? Prospective study of effects of clinical audit on rate of requests. BMJ 19973141729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lugli A, Anabitarte M, Beer J H. Effect of simple interventions on necropsy rate when active informed consent is required. Lancet 19993541391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlton R. Autopsy and medical education: a review. J R Soc Med 199487232–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]