Four recurrent chromosomal translocations are recognised in mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas: t(11;18)/API2‐MALT1, t(1;14)/IGH‐BCL10, t(14;18)/IGH‐MALT1 and t(3;14)/IGH‐FOXP1. In contrast, t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2, the genetic hallmark of follicular lymphoma, has been observed in only rare cases of MALT lymphoma. Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed an ulcer in erythematous granular mucosa at the gastric corpus in a 55‐year‐old man. A diagnosis of MALT lymphoma was made on the basis of typical histological and immunohistochemical features of biopsy specimens: a diffuse infiltrate of centrocyte‐like cells surrounding reactive lymphoid follicles and forming lymphoepithelial lesions, and a CD20+, IgD−, CD5−, CD10−, Bcl6−, cyclinD1− immunophenotype. Four months after the successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori, there was endoscopic regression with probable minimal residual disease detected by biopsy, but histological relapse was recognised 12 months after eradication. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation revealed t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2, but not the translocations typically seen in MALT lymphoma. This is the first report of a gastric MALT lymphoma with t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2 that responded to H pylori eradication.

Extranodal marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma of mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) is genetically characterised by the recurrent translocations t(11;18)(q21;q21)/API2‐MALT1, t(1;14)(p22;q32)/BCL10‐IGH, t(14;18)(q32;q21)/IGH‐MALT1 and t(3;14)(p14;q32)/FOXP1‐IGH.1,2 Recent evidence suggests that at least some of these translocations may be associated with distinct clinicopathological features.1,3 The t(14;18)(q32;q21)/IGH‐BCL2 is found in the majority of follicular lymphomas and some diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas.4 However, MALT lymphomas carrying this translocation are extremely rare and their clinical features are virtually unknown.

Case report

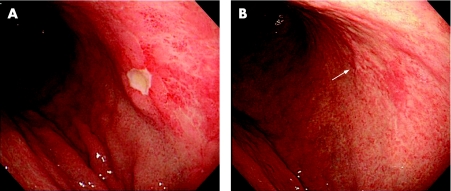

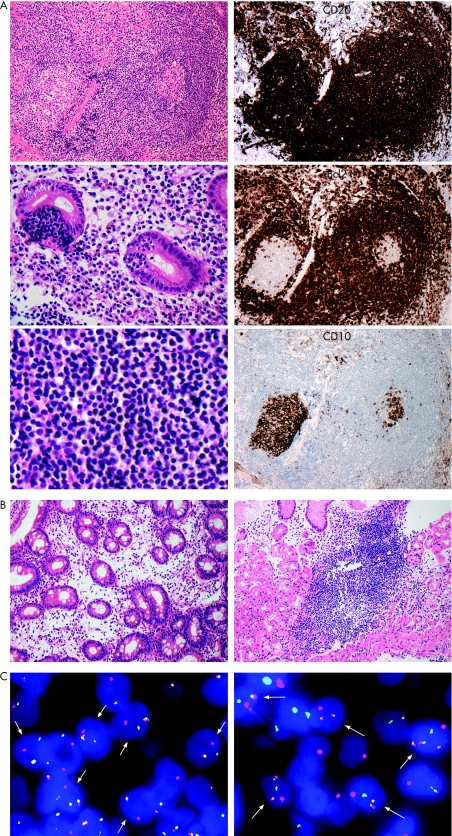

A 55‐year‐old asymptomatic man underwent oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) as screening for gastric carcinoma. OGD revealed an open ulcer with surrounding granular erythematous mucosa in the upper corpus (fig 1A). Histological examination of biopsy specimens taken adjacent to the ulcer margin and from nearby erythematous spots showed a diffuse infiltrate of centrocyte‐like and small lymphocyte‐like cells surrounding reactive lymphoid follicles in a marginal zone distribution, forming prominent lymphoepithelial lesions (fig 2A). Monocytoid differentiation and plasmacytoid cells with Dutcher bodies were also observed. Immunohistochemistry showed the neoplastic cells to express CD20, CD79a and Bcl2, but not CD3, CD5, CD10, CD43, Bcl6, cyclinD1 or IgD (fig 2A). On the basis of these findings, a diagnosis of MALT lymphoma was made.

Figure 1 (A) Pretreatment oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) revealed a superficial lesion comprising an open ulcer, multiple scars and erythematous granular mucosa on the posterior wall of the upper corpus. (B) Follow‐up OGD 4 months after Helicobacter pylori eradication showed regression of the initial lesion with multiple scars and mildly erythematous mucosa. The arrow indicates a healed scar from the ulcer in (A). Informed consent was obtained for publication of this figure.

Figure 2 (A) Histological and immunohistochemical features of pretreatment biopsy specimens taken from the erythematous mucosa adjacent to the ulcer. A diffuse infiltrate of CD20+, CD10− centrocyte‐like and small lymphocyte‐like cells surrounding reactive Bcl2− lymphoid follicles and forming typical lymphoepithelial lesions can be seen. (B) Histological pictures of follow‐up biopsy specimens 4 months after Helicobacter pylori eradication. A specimen obtained from the healed ulcer (fig 1B, arrow) shows mildly oedematous lamina propria with fibroblasts and scattered plasma cells and eosinophils, without evidence of lymphoma (left). However, another specimen taken from an erythematous spot displays aggregates of small lymphoid cells among fundic glands, consistent with probable minimal residual disease (right). (C) Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) with BCL2 dual‐colour break‐apart probe reveals splitting of the green and red signals (left, arrows). FISH with IGH/BCL2 dual‐colour, dual‐fusion translocation probe shows co‐localisation of the red and green signals (right, arrows), indicating t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2. Informed consent was obtained for publication of this figure.

Staging investigations including endosonography,5 CT of the chest and abdomen, colonoscopy, small bowel follow‐through, peripheral blood and bone marrow examination, and 18F‐fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography showed Lugano stage 1 disease.6H pylori was detected by the rapid urease test, histology and serology, and was eradicated with rabeprazole 40 mg/day plus amoxicillin 2000 mg/day for 2 weeks. Successful eradication of H pylori was confirmed by [13C]urea breath test 2 months after treatment. Serological investigation for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection was negative.

Follow‐up OGD 4 months after eradication showed disappearance of the initial lesion with small residual scars (fig 1B). Several biopsy specimens obtained from the scars and the surrounding mucosa displayed mildly oedematous lamina propria with scattered plasma cells and eosinophils, but no evidence of lymphoma. However, one specimen, taken from an erythematous spot, contained aggregates of small lymphoid cells (fig 2B), consistent with histologically defined probable minimal residual disease (pMRD).7 Further OGD and biopsy at 7 months also showed endoscopic regression with pMRD. However, histological relapse, defined as a definite lymphomatous infiltrate, was recognised at 12 months, despite the absence of endoscopically evident lymphoma. At this time, [13C]urea breath test, rapid urease test and histology all remained negative for H pylori. Follow‐up investigations at 15, 18, 21 and 24 months showed only atrophic changes endoscopically, although focal histological evidence of lymphoma was seen on several of the biopsy specimens taken. The patient is currently under careful observation without any additional treatment.

Molecular genetic findings

The presence of MALT lymphoma‐associated chromosome translocations was assessed by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) on formalin‐fixed, paraffin‐embedded tissues.2 FISH probes were obtained from Vysis/Abbott, Maidenhead UK, except for the FOXP1 and BCL10 break‐apart probes (kindly provided by Dr A Banham, Oxford, and Professor R Siebert, Kiel, respectively). FISH on pretreatment specimens showed a split signal with IGH and BCL2 break‐apart probes but not with MALT1, BCL10, BCL6, CCND1 or FOXP1 probes. FISH using a dual‐colour dual‐fusion translocation probe showed co‐localisation of IGH and BCL2 signals (fig 2C) indicating the presence of t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2. t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2 was also identified in follow‐up biopsy specimens, including those showing pMRD. Extra copies were observed by FISH with the MALT1 break‐apart probe and with the centromere‐specific probe for chromosome 18, but not with BCL2 or IGH probes. These findings suggest the presence of partial trisomy 18.

Discussion

Although the case reported in this study is positive for t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2, the diagnosis of MALT lymphoma is beyond doubt. This is supported by the characteristic histological and immunohistochemical findings: centrocyte‐like cells surrounding reactive lymphoid follicles, prominent lymphoepithelial lesions, and the CD20+, CD5−, CD10−, Bcl6−, IgD− and cyclinD1− immunophenotype. Follicular lymphoma occasionally develops in the stomach, and may mimic MALT lymphoma by showing parafollicular marginal zone differentiation and lymphoepithelial lesions.8 However, the neoplastic cells in the present case did not express the germinal centre B‐cell markers CD10 or Bcl6, and the follicles present in the specimens showed reactive morphological features and were Bcl2−.

t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2 is observed not only in follicular lymphoma, but also in about 20% of diffuse large B‐cell lymphomas, occasionally in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, and rarely in other lymphomas.4,9 This translocation has been identified in a few cases of MALT lymphoma, most notably in the salivary gland or stomach of patients with chronic HCV infection.10,11 Our patient was HCV negative, but had gastric colonisation by H pylori. Although H pylori eradication is now the first choice treatment for gastric MALT lymphoma,1,5 the translocation status of MALT lymphomas can influence their responsiveness to H pylori eradication. Most cases with a t(11;18)/API2‐MALT1 fail to respond to such treatment.12 The responsiveness to eradication therapy of patients carrying t(1;14)/IGH‐BCL10, t(14;18)/IGH‐MALT1 or t(3;14)/IGH‐FOXP1 is less well established. In the present case with t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2, H pylori eradication resulted in endoscopic regression with pMRD. Such pMRD is often observed in gastric MALT lymphomas after H pylori eradication.13,14 Although the long‐term clinical significance of pMRD remains to be elucidated, a watch‐and‐wait strategy is considered appropriate for such patients, including the present case.13,14

The mechanisms by which t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2 might promote and/or sustain a MALT lymphoma have not been established. Aiello et al10 reported a case of salivary gland MALT lymphoma in a patient with Sjögren syndrome, who developed a clonally related follicular lymphoma 2 years later. t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2 was detected in both the MALT and follicular lymphomas. The authors suggested that the follicular lymphoma might have resulted from colonisation of pre‐existing reactive follicles by t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2‐positive MALT lymphoma cells and subsequent interactions between the translocation and the germinal centre microenvironment. This hypothesis is in keeping with growing evidence that the characteristics of lymphoma cells may be influenced by the microenvironment in which they are set. In the present case, chronic H pylori infection may have provided conditions favouring the development and maintenance of MALT lymphoma. Within the germinal centre, forced over‐expression of the anti‐apoptotic protein Bcl2 by t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2 is thought to promote survival and expansion of the neoplastic clone.4 However, the role of the t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2 in MALT lymphoma is less clear as both normal marginal zone B cells and the majority of MALT lymphomas express Bcl2 in the absence of the translocation. Nevertheless, like other lymphoma‐associated translocations, t(14;18)/IGH‐BCL2 alone is probably insufficient for lymphoma formation, and, in the present case, over‐expression of Bcl2 is likely to cooperate with additional genetic abnormalities to promote the development of MALT lymphoma.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Reiner Siebert of the Institute of Human Genetics, University Hospital Schleswig‐Holstein, Kiel, Germany for providing the BCL10 probe, and Dr Alison H Banham of the Nuffield Department of Clinical Laboratory Studies, University of Oxford, UK for the FOXP1 probe.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by research grants from the Leukaemia Research Fund, UK. CB was supported by a Senior Clinician Scientist Fellowship from The Health Foundation, The Royal College of Pathologists and The Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

Competing interests: None declared.

Informed consent was obtained for publication of the person's details in this report.

References

- 1.Du M Q, Atherton J C. Molecular subtyping of gastric MALT lymphomas: implications for prognosis and management. Gut 200655886–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye H, Gong L, Liu H.et al MALT lymphoma with t(14;18)(q32;q21)/IGH‐MALT1 is characterized by strong cytoplasmic MALT1 and BCL10 expression. J Pathol 2005205293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sagaert X, de Paepe P, Libbrecht L.et al Forkhead box P1 expression in mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas predicts poor prognosis and transformation to diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2006242490–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willis T G, Dyer M J S. The role of immunoglobulin translocations in the pathogenesis of B‐cell malignancies. Blood 200096808–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Suekane H.et al Predictive value of endoscopic ultrasonography for regression of gastric low grade and high grade MALT lymphomas after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut 200148454–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohatiner A, d'Amore F, Coiffier B.et al Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol 19945397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Copie‐Bergman C, Gaulard P, Lavergne‐Slove A.et al Proposal for a new histological grading system for post‐treatment evaluation of gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut 2003521656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tzankov A, Hittmair A, Müller‐Hermelink H K.et al Primary gastric follicular lymphoma with parafollicular monocytoid B‐cells and lymphoepithelial lesions, mimicking extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of MALT. Virchows Arch 2002441614–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowakowski G S, Dewald G W, Hoyer J D.et al Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation with an IGH probe is important in the evaluation of patients with a clinical diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol 200513036–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aiello A, Du M Q, Diss T C.et al Simultaneous phenotypically distinct but clonally identical mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue and follicular lymphoma in a patient with Sjögren's syndrome. Blood 1999942247–2251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Libra M, De Re V, Gloghini A.et al Detection of bcl‐2 rearrangement in mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas from patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Haematologica 200489873–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H, Ye H, Ruskoné‐Fourmestraux A.et al t(11; 18) is a marker for all stage gastric MALT lymphomas that will not respond to H. pylori eradication. Gastroenterology 20021221286–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wündisch T, Thiede C, Morgner A.et al Long‐term follow‐up of gastric MALT lymphoma after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Clin Oncol 2005238018–8024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischbach W, Goebeler‐Kolve M, Starostik P.et al Minimal residual low‐grade gastric MALT‐type lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet 2002360547–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]