Abstract

Aims

To evaluate the activity of the European Medicines Evaluation Agency with regard to the registration for paediatric use of new medicines granted a marketing authorization.

Methods

European Public Assessment Reports published on the Internet from January 95 until April 98 have been analysed using the browser Microsoft Explorer and the software Adobe Acrobat Reader.

Results

Of the 45 new substances licensed since January 95, 29 (64%) were of possible use in children but only 10 were licensed for paediatric use. For the 19 drugs of possible use in children, but not approved for such a use, in nine instances (47%) their summary of product characteristics reported that their use in children has not been established.

Conclusions

A change of practice by pharmaceutical companies and regulatory authorities is imperative so that children are not precluded from having the same rights to medicines as adults.

Keywords: children, Europe, licensing, off-label medicines, survey

Introduction

The purpose of licensing is to control the manufacture, provision, promotion and supply of medicines. To fulfil that purpose medicines are examined by regulatory agencies for safety, efficacy and quality. The manufacturer can therefore advertise the drug only for the indications for which approval is obtained, and all promotion must be based on information approved for inclusion in the labelling of the drug. Labelling includes the summary of product characteristics and patient information leaflets, and is intended to provide all the information necessary for the drug to be used safely and effectively [1, 2].

Many new medicines and the vast majority of older medications have been approved without labelling for paediatric use because research for establishing their safety and efficacy in children has not been carried out [3].

The new European guidance on clinical investigation of medicinal products in children states that ‘children should not be given medicines which have not been evaluated for use in that age group’ [4]. The European legislation, however, makes provision for physicians to use medicines that do not have a marketing authorization (unlicensed) and for purposes other than those stated in the marketing authorization (off-label). Consequently, many medicines are prescribed for children without specific knowledge of the dosage, metabolism, half-life and potential side-effects. The absence of appropriate usage information of the product in paediatric patients prevents health professionals administering the drug in a manner that maximizes safety, minimizes unexpected adverse events, and optimizes treatment efficacy.

This longstanding underprivileged position of children in respect of medicines could be improved by the new European drug registration system supported by the European Medicines Evaluation Agency (EMEA). The aim of this new drug registration system is to give patients quick access to innovatory new drugs, to facilitate the free movement of drugs within the EC, and to provide rigorous scientific evaluation of new products [5].

The system, from January 98, uses two licensing procedures: the centralized procedure via the EMEA, which is compulsory for new biotechnology products, and a decentralized procedure. The latter, also called mutual recognition, enables manufactures to seek simultaneous marketing authorization in concerned member states, provided that they already have marketing authorization in at least one Member State [6].

For all products approved under the centralized procedure the EMEA issues the European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs). These reports give the reasons behind each approval, and contain a summary of product characteristics, and the information to be included in the patient information leaflet.

To determine the current status with regard to labelling for paediatric use of new medicines granted a marketing authorization by the EU on recommendation by the EMEA we systematically reviewed the information contained in the EPARs.

Methods

All the EPARs published on the World Wide Web from January 95 until April 98 have been analysed using the browser Microsoft Explorer and the software Adobe Acrobat Reader. EPARs are available for the public on the Internet as DPF files at the EMEA’s Web site.7

For each new medicinal product granted a marketing authorization through the centralized procedure, a check-list was prepared to gather basic information, such as the year of licensing, the manufacturer and its country of origin, the therapeutic area, the route of administration, and the main indications. We also considered more specific items, such as the labelling for paediatric use and the information in the summary of product characteristics concerning the use of the drug in children.

The applicability for paediatric use of drugs granted a marketing authorization has been established taking into account the prevalence of the target disease in the paediatric population, the clinical outcome of the disease in children, and the current availability of therapeutic alternatives. We considered applicable for use in children medicinal products for diseases affecting children exclusively (i.e. imiglucerase for Type 1 Gaucher disease) and drugs intended to treat diseases occurring in children and adults for which treatment exists (i.e. insulin lispro for diabetes mellitus) or for which there is currently no treatment (i.e. reverse transcriptase inhibitors for AIDS).

For the analysis, drugs were coded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic and Chemical Classification system (ATC) [8]. Data management and analysis were done using the Epi-Info software package.

Results

There have been 55 pan-European marketing authorizations since the establishment of the EMEA in January 1995; in particular, three brand products have been licensed during 1995, 24 in 1996, 23 in 1997, and 5 in 98 (up until April). The licensing procedure was undertaken by 40 manufacturers from 12 different countries, mainly from USA (27%) and Germany (21%).

The marketing authorizations concerned 45 different substances belonging to eight different ATC groups; the most common being general anti-infectives (22%), followed by antineoplastics and diagnostic agents (13% each).

Of the 45 centrally licensed substances, 29 (64%) were of possible use in children; 16 drugs were not applicable for use in children. Of the drugs of possible use in children, only 10 (34%) were licensed for children (Table 1), the remaining 19 drugs were not approved for use in the paediatric population (Table 2).

Table 1.

Drugs approved for use in children by the EMEA.

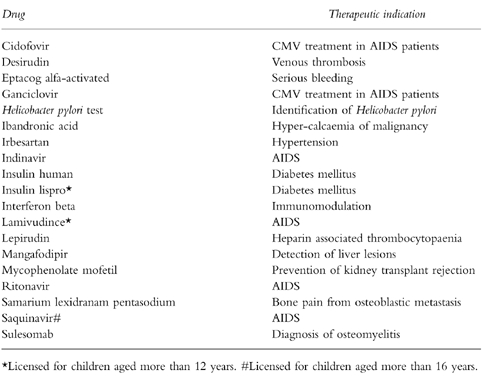

Table 2.

New medicines of possible use in children released by the EMEA without paediatric labelling.

For drugs of possible use in children, but not approved for such a use, in nine instances (47%) their summary of product characteristics reported that their use has not been established in children. In four instances drugs were released with paediatric disclaimers: interferon beta, lepirudin, cidofovir, and ibandronic acid. For two drugs the patient information leaflet contained no information concerning paediatric use: insulin human and eptacog alfa-activated. In four instances, the licensing for children was limited to specific age groups: for children aged more than 12 years for lamivudine, insulin lispro and ganciclovir; for children aged more than 16 years for saquinavir.

Concerning the formulations, of the 19 drugs of possible use but not licensed for children, 9 were available as injections, 8 as tablets, 3 as infusions and 2 as oral solutions. For three drugs, more than one formulation was available: oral solution and tablets for lamivudine and ritonavir, injection and infusion for insulin human. For the drugs available as tablets the number of strengths ranged from 1 to 3. Only in four instances were more than one strength available: two strengths for indinavir, ganciclovir and mycophenolate mofetil, three for irbesartan.

Discussion

Because paediatric drug evaluation has often been neglected, inadequate efficacy and safety information exists for a large number of drugs which are frequently used to treat childhood diseases [9].

The results of this survey disclose that most drugs that are indicated for diseases occurring in both adults and children have not been approved by the EMEA for use in the paediatric population.

This problem, however, is not unique to the European Community. A recently published review on the approval processes of drugs for children of the US Food and Drug Administration showed that 80% of the drugs approved during the past 30 years have been approved without paediatric labelling [10].

Moreover, the results of our survey also show that, just like the FDA, for the new medicines approved by the EMEA, the paediatric exclusionary labelling is not evenly distributed across therapeutic categories. Although certain medications, such as vaccines, generally are labelled for use in children, drugs in other important therapeutic categories by and large have not been approved for use in the paediatric population.

We are concerned that new drugs for the treatment of diabetes mellitus and AIDS are not licensed for use in children. These are conditions which affect an increasing number of children. We cannot comment on whether the pharmaceutical companies concerned have not sought a product licence for children or have not carried out the appropriate clinical trial in children.

The reasons for a drug being unlicensed in children are many. It is often because the drug has not been tested in children. This may due to financial constraints or because of the apparent difficulties with data design and ethics of testing drugs in children [11].

Most manufacturers are not interested in financing the studies necessary to develop appropriate paediatric labelling for off-patent drugs, mainly because of the relatively small market share. Regulatory agencies are therefore faced with the dilemma of either contraindicating the use of the product in children or including general information for which the scientific basis has not been demonstrated [12].

There is only limited information available on the extent of unlicensed and off-label use of drugs in children in hospital, and no information is available regarding such usage in children in the community. Only two studies have been carried out until now. In the first study, prescriptions for 166 patients admitted to a paediatric intensive care unit over a 4-month period were reviewed daily. One hundred and thirty-six patients (70%) received at least one unlicensed or off-label drug. Thirteen of the 95 drugs prescribed (14%) were unlicensed for use in children and 22 (23%) were administered off-label [13].

In the more recently published study, prescriptions for 609 patients admitted to paediatric medical and surgical wards were prospectively analysed. The authors found that of 2013 courses of drugs administered to paediatric inpatients, 506 (25%) were either unlicensed or off label uses [14].

The results of these studies show that physicians who treat children frequently prescribe drugs that have not been approved for paediatric patients. In fact, for the vast majority of indications, even in young paediatric patients, the benefits of using unlicensed or ‘off-label’ medications outweigh the risk of not using them.

The lack of approval for a paediatric use does not prevent physicians from prescribing an available drug in the best interest of their patients. The decision should be made with the knowledge that lack of paediatric indications is usually based on the fact that regulatory agencies have not received sufficient data from the manufacturer, according to its statutory mandate, to approve labelling for such a use.

However, because of the limited availability of formulations containing an appropriate dosage for children, this practice may lead to errors in administration and therefore the risk of adverse drug reactions will increase. In the absence of adequate studies in paediatric populations, it is not possible to predict the dosage requirements for optimal therapeutic outcome. Drug studies in adults may not adequately predict the pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic, or toxic properties of drugs in children [15].

A solution to the problem of off-label drug use in children requires a partnership between pharmaceutical industry, regulatory agencies, academicians, and private physicians. In Europe there have been tangible steps recently to increase and expand therapeutic research in children. The interest in this subject across Europe has resulted in the publication of the European Guidance on the clinical investigation of medicinal products [4]. The document recognized the widespread concern regarding performing clinical trials in children, particularly subjecting children to repeated invasive procedures. It however, serves as a reminder that trials can be performed in children without undue distress if designed and carried out by clinical pharmacologists experienced in caring for children. The new guidance should encourage pharmaceutical companies to carry out trials in children for conditions where there is either no or inadequate treatment at present, and where the product is likely to be used in children.

It is the hope of child health professionals and clinical pharmacologists that these new guidelines will result in a change of attitude by pharmaceutical companies and the regulatory authorities so that children are not precluded as having the same rights to medicines as adults.

Acknowledgments

Piero Impicciatore is a visiting Research Fellow from the ‘Mario Negri’ Institute, Milan (Italy), funded by a travel fellowship.

References

- 1.Choonara I, Dunne J. Licensing of medicines. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:67–69. doi: 10.1136/adc.78.5.402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatric Committee on Drugs. Unapproved uses of approved drugs: the physician, the package insert, and the Food and Drug Administration: subject review. Pediatrics. 1996;98:143–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner S, Nunn AJ, Choonara I. Unlicensed drug use in children in the UK. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther. 1997;1:52–55. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Note for guidance on clinical investigation of medicinal products in children. London: Medicines Control Agency; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herxheimer A. The European Medicines Evaluation Agency. Br Med J. 1996;312:394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7028.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham J, Lewis G. Secrecy and transparency of medicines licensing in the EU. Lancet. 1998;352:480–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11282-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. http: //www.eudra.org/emea.html.

- 8.WHO, NCM. 1990. Guidelines for ATC,—Classification. Oslo and Uppsala: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (Oslo) and Nordic Council on Medicine (Uppsala)

- 9.Cote′ CJ, Kauffman RE, Troendle GJ, lambert GH. Is the ‘Therapeutic Orphan’ about to the adopted? Pediatrics. 1996;98:118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kauffman RE. Status of drug approval processes and regulation of medications for children. Curr Opinion Pediatr. 1995;7:195–198. doi: 10.1097/00008480-199504000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joint Report of the British Paediatric Association and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry. London: 1996. Licensing medicines for children. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Essex C, Rylance G. Children have rights to medicines. Br Med J. 1997;315:62. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7099.62a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner S, Gill A, Nunn TJ, Hewitt B, Choonara I. Use of ‘off-label’ and unlicensed drugs in paediatric intensive care unit. Lancet. 1996;347:549–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner S, Longworth A, Nunn AJ, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off-label drug use in paediatric wards: prospective study. Br Med J. 1998;316:343–346. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Impicciatore P, Pandolfini C, Bosetti C, Bonati M. Adverse drug reactions in children: a systematic review of published case reports. Paediatr Perinat Drug Ther. 1998;2:27–36. [Google Scholar]