Abstract

Aims

To describe the psychiatric indications of neuroleptics (especially the relative share of schizophrenic and other psychotic disorders) and the usage patterns of these drugs (dose, duration, coprescriptions).

Methods

A one-day national cross-sectional survey in a random sample of 723 French psychiatrists was carried out in 1996. Each psychiatrist was asked to complete a standardized questionnaire for the first three patients seen the day of the survey to whom at least one neuroleptic was prescribed (initiated or renewed).

Results

One thousand seven hundred and fifty-four questionnaires were returned. Three quarters of the patients (74%) were psychotic (664 with schizophrenia, and 636 other psychosis), 19.3% were depressive and 6.7% had other psychiatric disorders. Phenothiazines were the most often prescribed (40.8%), followed by butyrophenones (22.5%), benzamides (15.8%), other neuroleptics (14.8%) and thioxanthenes (6.1%). Among schizophrenic subjects, an average number of 1.54 (95% CI: 1.50–1.60) neuroleptics were prescribed per patient, compared with 1.4 (95% CI: 1.32–1.41) and 1.2 (95% CI: 1.14–1.23) in other psychotic and depressive subjects, respectively. Regardless of the indication, non-neuroleptic psychotropic drugs were coprescribed in 75.4%, mainly benzodiazepines (75.7%). Adjuvant drugs used in prevention or treatment of side-effects were coprescribed in 46.7%, mostly anticholinergic antiparkinsonians (86.1%).

Conclusions

Neuroleptics are mainly prescribed for psychotic disorders and especially schizophrenia. However, current recommendations are not always followed.

Keywords: antipsychotic drugs, cross-sectional study, drug utilization study, France, pharmacoepidemiology

Introduction

Neuroleptics, or antipsychotic drugs, have been used in clinical practice for the treatment of psychotic illnesses since the 1950s, beginning with the introduction of chlorpromazine. There have been no major changes in this therapeutic class, other than the recent introduction of ‘atypical’ neuroleptics (clozapine, risperidone, sertindole, olanzapine, etc.). The choice between different neuroleptics is mainly based on the therapeutic response to the drugs and the occurrence of adverse reactions, but it has been shown that it can also be related to the sociodemographic characteristics of treated patients or the prescription setting (hospital, community, private or public) [1–4]. About 25 different neuroleptics belonging to five different chemical classes are currently available in France, but few studies have been conducted to assess their prescription patterns. These studies have been carried out with general practitioners or in specific populations such as schizophrenic or psychiatric in-patients. Recent recommendations attempt to limit (i) the prescription of neuroleptics to psychotic patients or those presenting with psychotic-like syndromes, (ii) the number of neuroleptics prescribed concomitantly and (iii) the coprescription of other psychotropic drugs or drugs to take account of side-effects (e.g. anticholinergic antiparkinsonian drugs) [5]. We therefore conducted a national cross-sectional survey in a random sample of French psychiatrists in 1996, to assess their neuroleptic drug prescription patterns.

The objectives of this study were to describe (i) the reasons for prescribing neuroleptics, especially the relative proportion of schizophrenia and other psychoses and (ii) neuroleptic prescription patterns in terms of dosage, duration of prescription and comedications.

Methods

Type of study and sample size

We conducted a 1 day cross-sectional survey on a representative sample of French psychiatrists. The main objective of this survey was to estimate the proportion of neuroleptic drugs prescribed for psychotic diseases (schizophrenia and others). In a previous study conducted in France among general practitioners, 64% of neuroleptics were prescribed to treat psychosis and 60% of these were initially prescribed by psychiatrists [1]. We therefore assumed that at least 70% of neuroleptics prescribed by psychiatrists would be prescribed for psychotic patients. From sales data, it appears that private psychiatrists were on average prescribing neuroleptics about 1.3 times a day and hospital psychiatrists about 3 times a day.

Using the formula proposed by Lemeshow [6], it was estimated that 896 prescriptions would be required (with α = 0.05, δ = 0.03 and P = 0.7) to estimate the percentage of prescriptions for psychoses. Taking into account incomplete reports and adjustment, we considered that a minimum of 1000 prescriptions (i.e. from about 500 participating psychiatrist) would be needed to estimate the relative proportion of the treatment of psychoses in neuroleptic prescriptions with a precision of 3%.

Study population and sampling

From an exhaustive national database of 9049 French psychiatrists and after exclusion of the lowest neuroleptics prescribers (i.e. psychoanalysts, child-psychiatrists), a random sample of 1876 psychiatrists was extracted, stratified on region and type of practice. Since we assumed a participation rate of around 40%, this number was considered sufficient to ensure the required number of participating psychiatrists. Three types of practice were considered: private practitioners, hospital practitioners and mixed, distributed among the 22 regions of France. In each stratum, proportional allocation was used to determine the number of psychiatrists to be selected. In the original database, 42.4% were ambulatory practitioners, 20.5% hospital practitioners and 37.1% had dual practices. Each psychiatrist not wishing to participate was randomly replaced by another psychiatrist of the remaining database in the same stratum. Seven hundred and twenty-three psychiatrists agreed to participate: 43.1% were private practitioners, 20.7% hospital practitioners and 36.1% were mixed. The distribution of this sample did not differ significantly from the source population according to region (Chi-square = 0.12, P > 0.9) or type of practice (Chi-square = 0.38; P = 0.83).

Data collected

Each psychiatrist was asked to complete a standardized questionnaire for the first three patients seen on or after October 22, 1996 to whom at least one neuroleptic was prescribed (initiated or renewed). Data collected included personal data (gender, age, way of life, etc.), duration of psychiatric care and first neuroleptic prescription (past and present), names and dosage of neuroleptic prescribed, names of coprescribed drugs (psychotropic or not), diagnosis motivating the prescription. In order not to influence the diagnosis of psychiatrists, we did not use an international scale such as ICD-10 or DSM IV to assess diagnoses. Psychiatrists were asked to specify neuroleptic indication from a list of psychiatric diagnoses (Table 2), according to their personal judgement.

Table 2.

Psychiatric diagnoses listed in the questionnaire.

Classification of neuroleptic drugs and psychiatric diagnoses

Neuroleptics were classified into five chemical categories according to the ‘Dictionnaire Vidal’, the French drug formulary: phenothiazines, butyrophenones, thioxanthenes, benzamides and other neuroleptics (including atypical neuroleptics, risperidone and clozapine) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Neuroleptic classification according to the ‘Dictionnaire Vidal’.

Psychiatric diagnoses were divided into four categories: schizophrenia, nonschizophrenic psychosis, depression and other psychiatric disorders.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed with the BMDP statistical package (version 1990).

To identify factors associated with neuroleptic prescription (i.e. multiple neuroleptic prescriptions, other concomitant medications), bivariate analyses were first performed, using chi-square tests. When the association was significant (P < 25%), stepwise logistic regression techniques were used. P values below 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Of 723 psychiatrists who agreed to participate, 624 (86.7%) returned at least one questionnaire: 43.1% of volunteers and 44.5% of respondents were private practitioners, 20.7% of volunteers and 20.3% of respondents hospital practitioners and 36.1% of volunteers and 35.1% of respondents were both (Chi-square = 0.27; P = 0.87). A total of 1754 questionnaires were returned to the coordinating centre (i.e. an average of 2.9 per psychiatrist for hospital practitioners, 2.7 for the private practitioners and 2.9 for psychiatrists with dual practices). All the questionnaires were included in the analysis.

Characteristics of patients

The mean age of patients was 41.3 years (s.d.: 13.8). Nine percent of patients were under 25 years of age, 53.5% between 25 and 44 years, 30.1% between 45 and 65 years and 7.2% were 65 and over. Sex ratio was 1.07 (51.7% male and 48.3% female). Half the patients (51.8%) were single, 32.9% married, 11.0% divorced and 4.3% widowed. Half the prescriptions (50.8%) came from private consultations, 22.9% from outpatient clinics and 26.3% concerned hospitalized patients. According to the psychiatrists’ diagnosis, three quarters of the patients (n = 1,300, 74%) were psychotic (664 schizophrenia, 636 other psychoses), 19.3% (337) were depressed and 6.7% (117) had other psychiatric disorders. Among depressed patients, 141 (41.8%) had chronic depressive disorders and 105 (31.1%) bipolar depression.

General neuroleptic prescriptions patterns

The average number of neuroleptics prescribed per patient was 1.4 (95% CI: 1.37–1.42), polypharmacy (the prescription of more than one neuroleptic), was observed in 34.4% of prescriptions.

The majority of the prescriptions (87%) were renewals. Phenothiazines were the most commonly prescribed class of neuroleptics (40.8%), followed by butyrophenones (22.5%), benzamides (15.8%), atypical neuroleptic (14.8%) and thioxanthenes (6.1%). The most frequently prescribed oral forms were: cyamemazine (20.5%), haloperidol (16.3%), amisulpride (13.0%), risperidone (8.1%), levomepromazine (8.4%), loxapine (5.7%) and acepromazine (4.3%) (Table 3). Almost all risperidone prescriptions (96.8%) were for psychotic patients.

Table 3.

Neuroleptic prescriptions according to the diagnosis, n (%).

Oral neuroleptics were prescribed in 81.4%, depot neuroleptics in 16.3% and short-acting parenteral forms in 2.1%. Oral and depot forms were associated in 51.7%.

For treatment by a single neuroleptic, amisulpride was the most commonly prescribed drug. In case of bi-therapy, the most frequent association (36.2%) was of phenothiazines and butyrophenones. In case of tri-therapy, a phenothiazine was always present.

Non-neuroleptic psychotropic drugs were coprescribed in 1323 (75.4%) prescriptions: a benzodiazepine in 75.7%. Antidepressants were coprescribed in 37.2% of schizophrenic, in 50.8% of other psychotic and 81.7% of depressive disorders (Table 4).

Table 4.

Patterns of neuroleptic prescriptions according to the diagnosis.

Co-prescription or adjuvant drugs intended to counter side-effects (extra-pyramidal symptoms, anticholinergic effects) was present in 822 (46.7%) prescriptions. Anticholinergic antiparkinsonian drugs accounted for 708 (86.1%) prescriptions.

Patterns according to neuroleptic indication (Table 4)

We considered only three groups of indications: schizophrenia (n = 664), other psychoses (n = 636) and depressive disorders (n = 337). The remaining indications include a great variety of diagnoses and were not considered as a whole because of their heterogeneity or individually because of the low number of subjects per diagnosis.

Polypharmacy was significantly higher in schizophrenia. The average number of neuroleptics was 1.54 (95% CI: 1.50–1.60) compared with other psychoses (1.37; 95% CI: 1.32–1.41) or depressive disorders (1.20; 95% CI: 1.14–1.23).

Phenothiazines were more prescribed in depressive disorders (56.8% of prescriptions) than in schizophrenia (39.4%) or other psychoses (34.4%). Concomitant non-neuroleptic psychotropic drugs were prescribed in 67.2% in schizophrenia vs 75.5% in other psychoses and 94% in depressive disorders. Whatever the indication, the associated psychotropic was a benzodiazepine in more than 70% of prescriptions. Concomitant adjuvants were found in 58.3% of cases of schizophrenia, in 45.6% of other psychoses and in 35.0% of depressive disorders.

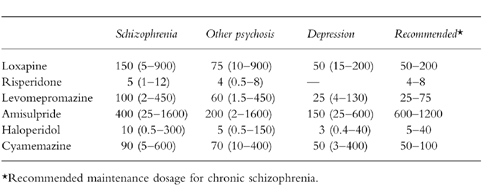

Dosage was considered for neuroleptics totalling at least 100 prescriptions (Table 5). Because of small numbers of prescriptions of each drug, dosage was expressed as the median value (in mg) according to diagnosis and compared with the recommended maintenance dosage for chronic schizophrenia [5]. When the prescription was done for schizophrenic patients, the dosages remained within the recommended range. In the case of other psychoses, dosage was included within the recommended range except for amisulpride for which the dosage was lower than recommended. In depressed patients, all neuroleptic dosages were below or equal to the lower limit of recommended ranges.

Table 5.

Dosages of the most prescribed neuroleptics (median and in mg) according to diagnosis

Factors associated with polypharmacy (prescription of more than one neuroleptic) (Table 6)

Table 6.

Factors associated with the prescription of more than one neuroleptic (logistic regression model).

Polypharmacy was significantly associated with the duration of neuroleptic treatment: compared with neuroleptic treatment started 5 years or more ago, the odds ratio for polypharmacy was 2.0 (95% CI: 1.60–2.50) for treatment started more than 5 years ago. Polypharmacy varied significantly with the indication of the neuroleptic treatment. When neuroleptic prescription was done for other psychoses or depressive disorders, the probability of polypharmacy was lower compared with schizophrenia (OR = 0.71; 0.56–0.91 and OR = 0.35; 95% CI: 0.25–0.50, respectively). Compared with ambulatory prescriptions, those in hospitalized patients or in out-clinics tended to include more than one neuroleptic (OR = 2.90; 95% CI: 2.1–3.7, OR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.20–2.0, respectively). Men more often received several neuroleptics than women (OR = 1.45; 95% CI: 1.16–1.81).

Factors associated with concomitant prescriptions of non-neuroleptic psychotropics (Table 7)

Table 7.

Factors associated with the coprescription of other psychotropics (logistic regression model).

Concomitant prescriptions of other psychotropic drugs increased with age. Compared with patients under 20 years, concomitant psychotropic drugs were more common in patients aged 25–40 years (OR = 1.60; 95% CI: 1.10–2.35) and 40 or more (OR = 1.97; 95% CI: 1.20–30). Concomitant prescription was also more common in depressive disorders (OR = 4.1: 95% CI: 2.40–7.0), when subjects presented with more than one other psychiatric symptom (OR = 1.67; 95% CI: 1.30–2.15), and when duration of treatment was 5 years or more (OR = 1.72; 95% CI: 1.33–2.23).

Factors associated with concomitant prescription of correctors of side-effects (Table 8)

Table 8.

Factors associated with the coprescription of adjuvants (logistic regression model).

Compared with other neuroleptics, concomitant prescriptions of adjuvants were significantly associated with phenothiazine prescriptions (OR = 1.50; 95% CI: 1.10–2.10), butyrophenones (OR = 2.75; 95% CI: 2.0–3.73) and thioxanthenes (OR = 2.60; 95% CI: 1.65–4.0) but not with benzamides (OR = 0.90; 95% CI: 0.65–1.26). It increased with duration of neuroleptic treatment (duration ≥5 years: OR = 1.62; 95% CI: 1.30–2.0), with prescription in hospital (OR = 2.3; 95% CI: 1.8–2.9) or in outpatient clinics (OR = 1.7; 95% CI: 1.3–2.2). Compared with schizophrenia, association was less frequent when the indication was of other psychoses (OR = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.5–0.9) or depressive disorders (OR = 0.50; 95% CI: 0.36–0.67).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first survey of neuroleptic prescription conducted in a representative sample of French psychiatrists. As psychiatrists are the main initial prescribers of neuroleptics (general practitioners generally renew rather that initiate treatment), the reliability of patterns is reinforced.

Because of its relatively participation rate, a selection bias cannot be formally excluded, i.e. if the nonrespondents are more likely low-prescribers of neuroleptics, we could have overestimated the average number of neuroleptics prescribed per patients.

According to the results of this survey, psychosis is the main indication for neuroleptic prescription (37.8% of patients were schizophrenic and 36.2% had another psychoses). Although neuroleptic use has been discouraged for mood disorders [7], 19% of neuroleptic prescriptions were for depression or associated disorders. However 31.1% of them had a manic-depressive illness and 51.7% personality disorders. As expected, butyrophenones were most commonly prescribed for psychotic patients at the usually recommended dosage and phenothiazines for depressive disorders at a dosage lower than that recommended for psychoses, generally considered as having sedative effects. The average duration of treatment (5 years) and the proportion of repeat prescriptions (87%) indicated that neuroleptics are mainly used for long-term treatment. This was obviously expected because of the chronicity of psychiatric diseases. However, because of the cross-sectional design of the study, it was difficult to make the difference between continuous and intermittent treatments. Polypharmacy was more prevalent among schizophrenic patients (39%) than in other psychotic (28%) or depressed patients (16%). A survey conducted in 1992 in schizophrenic patients reported polypharmacy in 73% of prescriptions in Spain and 46% in Estonia and Sweden [8]. It was 33% in an Italian survey conducted in different psychiatric settings [9]. In a recent survey conducted in mental health services of Piedmont, Italy, polypharmacy was more frequent in hospitalized than in ambulatory patients [10]. Regardless of indication, polypharmacy was associated with duration of treatment, which could correspond to an increase in the severity of disease over time, requiring concurrent prescriptions of neuroleptics with different profiles. It could also correspond to long-standing well-tolerated treatments that physicians do not change in stabilized patients. Combination with other psychotropics drugs was relatively common (75.4% for benzodiazepines and 41% for antidepressants). This reflects the complexity of treating psychiatric symptoms with neuroleptics only and the fact that in depressed patients, neuroleptics are not the first line treatment. Regardless of the diagnoses associated with neuroleptic prescription, combination with other psychotropic drugs was more frequent for people over 45 years of age. This is consistent with the increased use of psychotropics observed in older subjects [11]. Medications intended to prevent or treat neuroleptic side-effects were combined in 46.7% of prescriptions. Of these, 86.1% were anticholinergic antiparkinsonian drugs. These drugs are routinely used to treat extrapyramidal symptoms to which most patients are prone during neuroleptic treatment. This combination was more common in psychotic patients who are the most likely to receive high doses of neuroleptics, often on a long-term basis. It was also more often encountered when prescriptions included ‘classic’ neuroleptics (phenothiazines, butyrophenones or thioxanthenes). According to the French consensus group on neuroleptic prescription [5], use of anticholinergic antiparkinsonians is not recommended for prophylaxis of extrapyramidal syndrome but should only be prescribed in patients with extrapyramidal symptoms. Even though classical neuroleptics (which are the most prescribed) are associated with a high risk of extrapyramidal syndrome, it is doubtful that the observed 50% coprescription frequency is explained only by corrective indications. One may also note that these correctors were less used with the new atypical neuroleptics and with benzamides, which are known to induce fewer extrapyramidal syndrome than classical neuroleptics. In conclusion, this study shows that neuroleptics are mainly prescribed for psychotic disorders and especially schizophrenia. However, it should be emphasized that current recommendations are not always followed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Nicholas Moore, for his helpful comments. This work was supported by a grant from Lilly France.

References

- 1.Approche pharmaco-épidémiologique de la prescription des neuroleptiques par les médecins généralistes. Etude THALES. Personal Communication. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fourrier A, Letenneur L, Dartigues JF, Bégaud B. Consommation de psychotropes chez le sujet âgé. Données la Cohorte PAQUID Revue Gériatrie. 1996;21:473–482. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lachaux B, Gaussares C. Le patient sous neuroleptique. 1994. JAMA(Suppl)to the French edition, octobre.

- 4.Casadebaig F, Philippe A, Gausset MF, Guillaud-Bataille JM, Quemada N, Terra JL. Accès aux soins somatiques et morbidité de patients schizophréniques. Internal Report. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prescription des neuroleptiques. Recommandations de Pratique Clinique (tome 2) ANDEM. Paris: 1994. pp. 211–242. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW, Klar J, Lwanga SK. Adequacy of sample size in health studies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sernyak MJ, Woods WS. Chronic neuroleptic use in manic-depressive illness. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1993;29:375–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiivet RA, Llerena A, Dahl ML, et al. Patterns of treatment of schizophrenic patients in Estonia, Spain and Sweden. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;40:467–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb05791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muscettola G, Casiello M, Bollini P, Sebastiani G, Pampallona S, Tognoni G. Pattern of therapeutic intervention and role of psychiatry settings: a survey in two regions of Italy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1987;75:55–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1987.tb02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tibaldi G, Munizza C, Bollini P, Pirfo E, Punzo F, Gramaglia F. Utilization of neuroleptic drugs in Italian mental health services: a survey in Piedmont. Psychiatric Services. 1997;48:213–217. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legrain M, Lecomte Th. The consumption of psychotropics in France and some European countries. Ann Pharm Fr. 1998;56:67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]