Abstract

Aims

To examine the potency of ticlopidine (TCL) as an inhibitor of cytochrome P450s (CYP450s) in vitro using human liver microsomes (HLMs) and recombinant human CYP450s.

Methods

Isoform-specific substrate probes of CYP1A2, 2C19, 2C9, 2D6, 2E1 and 3A4 were incubated in HLMs or recombinant CYPs with or without TCL. Preliminary data were generated to simulate an appropriate range of substrate and inhibitor concentrations to construct Dixon plots. In order to estimate accurately inhibition constants (Ki values) of TCL and determine the type of inhibition, data from experiments with three different HLMs for each isoform were fitted to relevant nonlinear regression enzyme inhibition models by WinNonlin.

Results

TCL was a potent, competitive inhibitor of CYP2C19 (Ki = 1.2 ± 0.5 µm) and of CYP2D6 (Ki = 3.4 ± 0.3 µm). These Ki values fell within the therapeutic steady-state plasma concentrations of TCL (1–3 µm). TCL was also a moderate inhibitor of CYP1A2 (Ki = 49 ± 19 µm) and a weak inhibitor of CYP2C9 (Ki > 75 µm), but its effect on the activities of CYP2E1 (Ki = 584 ± 48 µm) and CYP3A (> 1000 µm) was marginal.

Conclusions

TCL appears to be a broad-spectrum inhibitor of the CYP isoforms, but clinically significant adverse drug interactions are most likely with drugs that are substrates of CYP2C19 or CYP2D6.

Keywords: antiplatelet, cytochrome P450, inhibition, ticlopidine

Introduction

Many adverse drug–drug interactions of clinical interest appear to be attributable to pharmacokinetic changes that can be understood in terms of alterations of hepatic drug metabolic pathways catalysed by the cytochrome P450 system [1, 2]. The two major reasons for drug interactions involving the CYP450 system are induction or inhibition, with inhibition appearing to be more important in terms of documented clinical problems [2].

TCL is a potent inhibitor of platelet aggregation that has been widely used for the prevention of thrombosis after placement of coronary stents and for the prophylactic management of thromboembolic events involving abnormal platelet activity in patients with cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease and ischaemic heart disease [3]. The plasma concentrations and/or toxicity of a number of drugs whose elimination pathways appear to involve different CYP450 isoforms have been noted to increase when TCL is concomitantly administered. These drugs include phenytoin [4–10], omeprazole [11], theophylline [12], carbamazepine [13], R-warfarin [14] and antipyrine [15]. Upon consideration of the primary metabolic pathways of these drugs [1], it is reasonable to suspect that TCL inhibits multiple CYP450 isoforms including 2C19, 2C9, 1A2 and 3A. Although published data on the isoforms responsible are unavailable, it is possible that TCL itself is a CYP450 substrate as it undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism [16] and as cimetidine, a nonspecific inhibitor of CYP450, has been shown to decrease its clearance by ≈50% [17]. It follows that TCL can competitively inhibit the metabolism of drugs that are catalysed by the same enzyme. Recently, we presented in vitro evidence that TCL is a potent inhibitor of CYP2C19 [4, 5], but its effect on other isoforms is not systematically investigated. To allow prediction of drug interactions with TCL, we tested the inhibitory potency of TCL on the activities of six common drug-metabolizing CYP450s in vitro, using known marker substrates.

Methods

Chemicals

Ticlopidine HCl, phenytoin, phenacetin, paracetamol, chlorpropamide, midazolam, dextromethorphan, chlorzoxazone, G6P, G6PDH, NADP, and the disodium salt of EDTA were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO). (S)-mephenytoin, 4-hydroxymephenytoin, 6-hydroxychlorzoxazone, 4-hydroxymidazolam and 4-methylhydroxytolbutamide were purchased from Ultrafine Chemicals (Manchester, UK). Levallorphan was obtained from U.S.P.C. (Rockville, MD). Flurbiprofen and 4′-hydoxyflurbiprofen were provided by one of the authors (T.T.). Dextrorphan and 3-methoxymorphinan were purchased from Hoffman-La Roche, Inc. (Nutley, NJ). N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) butamide was kindly provided by John Strong (Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, MD). Other reagents were of h.p.l.c. grade.

Human liver microsomes (HLMs) and recombinant human CYP450s

The HLMs used were prepared from human liver tissue that was medically unsuitable for liver transplantation and frozen at −80°C within 3h of cross-clamp time. The characteristics of liver donors, procedure for preparation of microsomal fractions and their CYP450 contents have been described elsewhere [18]. The microsomal pellets were re-suspended in a reaction buffer (0.1 m Na+ and K+ phosphate, 1.0 mm EDTA, 5.0 mm MgCl2, pH7.4) to a protein concentration of 10 mg ml−1 (stock) and were kept at −80°C until used. Protein concentrations were determined using established method [19]. The apparent kinetic parameters (Km and Vmax values) of isoform-specific reaction probes in the livers used have been documented in earlier publications [20, 21].

Baculovirus-insect cell expressed human CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 (with reductase) were purchased from Gentest Corporation (Woburn, MA) and stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations and CYP450 contents were supplied by the manufacturer.

Inhibition of CYP450 by TCL

Using incubation conditions specific to each isoform that were linear for time, substrate and protein concentrations [21], isoform specific substrate probes were incubated in duplicate at 37°C with HLMs (or recombinant human CYP450s) and NADPH-generating system in the absence (control) or presence of varying concentrations of TCL. The reaction probes used were: phenacetin O-deethylation to paracetamol for CYP1A2 [22], tolbutamide 4-methylhydroxylation to 4-methyl-OH-tolbutamide [23] and flurbiprofen 4′-hydroxylation to 4-OH-furibuprofen for CYP2C9 [24], (S)-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation to 4′-OH-mephenytoin for CYP2C19 [25], dextromethorphan O-demethylation to dextrorphan for CYP2D6 [26], midazolam 4-hydroxylation to 4-OH-midazolam [27] and dextromethorphan N-demethylation to 3-methoxymorphinan for CYP3A [28], and chlorzoxazone 6-hydroxylation to 6-OH-chlorzoxazone for CYP2E1 [29]. Unless specified, a 5 min preincubation was carried out before the reaction was initiated by adding HLMs. For each inhibition study, preliminary incubation experiments were carried out using a single substrate concentration around its Km and a range of TCL concentrations (1–160 µm). Simulation of the preliminary data thus obtained was then used to generate appropriate substrate and inhibitor concentrations for the determination of a precise inhibition constant (Ki value) for each isoform. Dixon plots for the inhibition by TCL of each substrate probe were performed in three different HLMs. To test for mechanism-based inhibition of CYP isoforms by TCL, HLMs were preincubated with an NADPH-generation system with or without TCL (1–100 µm) for 0–30 min and then a 30 min further incubation was started by adding a substrate probe.

After termination of the incubation reactions with appropriate reagents, samples were centrifuged and injected into an h.p.l.c. system either directly or after reconstitution with mobile phase. The concentrations of the metabolites and internal standards were measured by h.p.l.c. method with u.v. or fluorescent detection specific for each assay. Rates of production of each metabolite from the substrate probes were quantified by using the ratio of area under the curve (AUC) of the metabolite to AUC of each internal standard using an appropriate standard curve. The rates of metabolite formation from substrate probes in the presence of TCL were compared with controls in which the inhibitor was replaced with vehicle.

H.p.l.c

Instruments used for h.p.l.c. were controlled by a Waters (Milford, MA) MillenniumTM 2010 Chromatography Manager and included a Waters Model 510 or 600 h.p.l.c. pump, Waters 710B or 717 Autosampler, Waters 490 or 484 u.v. detector, and Spectrovision FD-300 Dual Mono-chromator Fluorescence Detector (Groton Technology Inc., Concord, MA).

(S)-mephenytoin assay (CYP2C19)

The measurement of CYP2C19 catalysed (S)-mephenytoin 4-hydroxylation was by a method described earlier [21, 25]. TCL (0–100 µm) was incubated with a reaction mixture consisted of 5 mg ml−1 microsomal protein (HL4, HL8 and HL9), 5 mm potassium phosphate buffer, 25 µl of (S)-mephenytoin (25–200 µm) and NADPH-generating system (0.5 mm NADP, 2.0 mm G6P, 0.4 U ml−1 G6PDH, 0.1 mm EDTA, and 4.0 mm MgCl2) (final volume 250 µl) for 120 min and reactions were terminated by adding 100 µl acetonitrile. After adding internal standard (50 µl 20 µgml−1 phenytoin), 3 ml methylene chloride were added and the organic layer dried by speed vacuum after centrifuging at 2000 rev min−1 for 5 min. Dried pellets were reconstituted with 250 µl mobile phase and 100 µl was injected into the h.p.l.c. apparatus. Separation was done using isocratic elution from a MicrosorbTM C18 column at a flow rate of 0.7 ml min−1 in a mobile phase (26% acetonitrile in 0.05 m potassium phosphate, pH 4.0) and detected using an u.v. wavelength of 211 nm.

Dextromethorphan assay (CYP2D6 and CYP3A)

The CYP2D6 and CYP3A catalysed dextromethorphan O-demethylation to dextrorphan and N-demethylation to 3-methoxymorphinan, respectively, were evaluated essentially according to the method described by Broly et al. [26] and Gorski et al. [28]. A range of dextromethorphan concentrations (2.5–75 µm) were incubated with or without TCL (0–40 µm) for 30 min at 37 °C in a reaction mixture that consisted of HLMs (HL5, HL8 and HL16; final protein concentration, 80 µg ml−1), 80 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and NADPH-generating system (1.3 mm NADP, 3.3 mm G6P, 0.4 U ml−1 G6PDH, and 3.3 mm MgCl2). Incubations were terminated by adding 20 µl 60% perchloric acid. After adding internal standard (40 µl 16 µm levallorphan), the tubes were then centrifuged in an Eppendorf model 5415C microfuge (Brinkman Instruments, Westbury, NY) at 14 000 rev min−1 for 5 min and 40 µl of supernatant were used for analysis. H.p.l.c. separation was carried out using a DuPont Zorbax SB-Phenyl 150 × 4.6mm column and a mobile phase consisting of 5.7 mm monobasic potassium phosphate, 23% acetonitrile, 20% methanol and 0.114% triethyl-amine, pH4.0 (flow rate: 0.5 ml min−1). Fluorescent detection was done at an excitation wavelength of 200 nm and an emission wavelength of 304 nm. Midazolam was used as additional probe of CYP3A and assayed as described elsewhere [27].

Tolbutamide assay (CYP2C9)

The incubation method for tolbutamide 4-methylhydroxy- lation was the same as those for CYP2D6 and CYP3A described above except that the incubation time was 1 h. Microsomes from HL4, HL8 and HL9 were used. The concentration of tolbutamide was 30–100 µm and for TCL it was 15–60 µm. Chlorpropamide (15 µl of 0.1 mg ml−1) was the internal standard. After incubation, 1 ml of ethylether was added and protein was precipitated by centrifugation at 15000 rev min−1 for 5 min. The organic phase was dried by speed vacuum, reconstituted in 100 µl of mobile phase and then 75 µl was injected into an h.p.l.c. Chromatography was carried out according to Relling et al. [23] after slight modification [21].

Because tolbutamide methylhydroxylation is primarily oxidized by CYP2C9, it has been used over the years to probe the activity of this isoform in vitro and in vivo [23, 30]. There is also evidence that implicate CYP2C19 in this metabolic pathway [31]. Given that TCL is a strong inhibitor of this isoform relative to CYP2C9 [4] and that ticlopidine slows the elimination of phenytoin [4–10], a substrate of both CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 [32], we decided to characterize in more detail the inhibitory effect of TCL on CYP2C19 and CYP2C9. We used two approaches. We tested first whether tolbutamide is metabolized by both CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 isoforms and evaluated the relative inhibitory effect of TCL on tolbutamide methylhydroxylation. Tolbutamide (50 µm) was incubated without or with ticlopidine (0–60 µm) in recombinant human CYP2C19 and CYP2C9. The incubation condition was the same as that for HLMs described above. Our preliminary data suggested the role of CYP2C19 in tolbutamide metabolism. Second, we used flurbiprofen 4′-hydroxylation as an additional substrate probe to further assess the relative inhibitory effect of TCL on CYP2C9 activity [24]. Flurbiprofen (1–10 µm) was incubated without or with TCL (0–150 µm) in HLMs and assayed according to a method described by Tracy et al. [24].

Phenacetin assay (CYP1A2)

The CYP1A2 catalysed O-deethylation of phenacetin to paracetamol (acetaminophen) was measured according to a method described elsewhere [22] with modifications [21]. The reaction mixture consisted of phenacetin (30–100 µm), HLMs (HL8, HL10, or HL15; final protein concentration 1 mg ml−1 protein), NADPH-generating system (1.2 mm NADP, 11.1 mm G6P, 1.3 U ml−1 G6PDH, 1.0 mm EDTA and 5.0 mm MgCl2) and 0.1m phosphate buffer (pH7.4) was incubated for 30 min in the absence or presence of TCL (25–100 µm) for 30 min.

Chlorzoxazone assay (CYP2E1)

The effect of TCL (0–160 µm) on the rate of CYP2E1 catalysed 6-hydroxychlorzoxazone formation from chlorzoxazone (5–50 µm) was evaluated through the method described elsewhere [29]. The HLMs used were prepared from HL8, HL10, HL11 and HL15.

Data analysis

The reaction velocity of each substrate probes in the presence of TCL were expressed as percentage of the control velocity with no TCL present. Approximate initial Ki values were calculated from experiments that were conducted using single substrate and multiple TCL concentrations with use of the following equation assuming competitive inhibition:

where I is TCL concentration, Ki inhibitory constant, S substrate concentration and Km substrate concentration at half of the maximum velocity (Vmax) of the reaction.

Estimated Ki values from this analysis were used to generate computer-simulated optimal concentrations of substrate and TCL for the determination of Dixon plots. The Ki values obtained from Dixon and secondary Lineweaver-Burk plots were used as initial estimates for the determination of the exact Ki values by nonlinear least square regression analysis using WinNonlin Version 1.5 (Scientific Consulting, Inc., Apex, NC). The inhibition data were fitted to different models of enzyme inhibition. The appropriate type of inhibition model for each data set was selected on the basis of visual inspection of Dixon plots, the size of the sum of squares of residuals, AIC and SC values, the standard error and 95% confidence interval of the parameter estimates and the random distribution of the residuals from nonlinear regression analysis.

Results

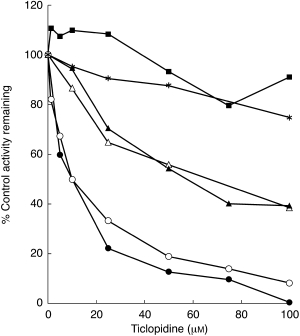

Incubation of a single concentration of the substrate reaction probe around its respective Km value with multiple TCL concentration (0–100 µm) in HLMs (HL8) showed that TCL is a potent inhibitor of CYP2C19 and of CYP2D6, and a relatively moderate inhibitor of CYP1A2 and CYP2C9, with little effect on the activities of CYP2E1 and CYP3A catalysed substrate probe reactions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of CYP450 isoforms by ticlopidine (0–100 µm) in HLMs (HL8). The activities of each isoform were measured by isoform-specific substrate reaction probes at approximately their respective Km values: 75 µm for phenacetin O-deethylation (CYP1A2, ▵), 50 µm for tolbutamide 4-methylhydroxylation (CYP2C9, ▴), 30 µm for (S)-mephenytoin 4-hydroxylation (CYP2C19, •), 20 µm for dextromethorphan (CYP2D6, ○), 25 µm for midazolam 4-hydroxylation (CYP3A, ▪), and 10 µm for chlorzoxazone (CYP2E1, ⋆). Data represent averages of duplicates and are expressed as percentage control activity remaining.

These preliminary data were then used to simulate appropriate range of substrate and inhibitor concentrations to construct Dixon plots for the inhibition of CYP isoforms by TCL in HLMs. The data obtained from experiments with at least three HLMs for each isoform were used to precisely estimate the corresponding inhibition constants (Ki values). In Table 1, the mean Ki values (±s.d.) estimated by WinNonlin using appropriate nonlinear regression models for enzyme inhibition are summarized.

Table 1.

Inhibition of CYP isoforms by ticlopidine. Data obtained from three HLMs to construct Dixon plots were fitted to an appropriate nonlinear regression enzyme inhibition model to calculate the inhibition constants (Ki values) for each isoform. The mechanism of inhibition was decided graphically and from the enzyme inhibition models (see Methods section).

| Substrate reaction probes | CYP450 isoforms | Ki (s.d. µm) | Mechanism of inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| (S)-Mephenytoin 4-hydroxylation | CYP2C19 | 1.2 (0.5) | Competitive* |

| Dextromethorphan O-demethylation | CYP2D6 | 3.4 (0.3) | Competitive |

| Phenacetin O-deethylation | CYP1A2 | 49 (19) | Competitive |

| Tolbutamide 4-methylhydroxylation | CYP2C9 | 76 (11) | Competitive |

| Flurbiprofen 4′-hydroxylation | CYP2C9 | 89 (12) | Noncompetitive |

| Chlorzoxazone 6-hydroxylation | CYP2E1 | 584 (148) | Competitive |

| Midazolam 4-hydroxylation | CYP3A | none** | |

| Dextromethorphan N-demethylation | CYP3A | none** |

Data equally fitted to competitive and noncompetitive model

estimated Ki > 1 mm.

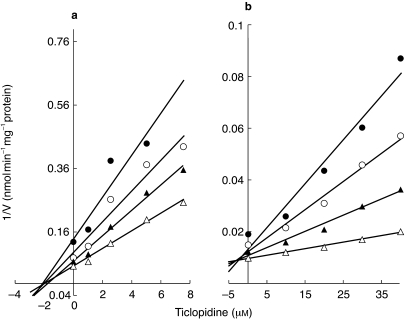

TCL consistently inhibited CYP2C19 mediated (S)-mephenytoin 4-hydroxylation (Table 1, and Figures 1 and 2a). The mean Ki value (1.2 µm) (Table 1) derived from three different HLMs concurs with the steady-state plasma concentrations of TCL at its recommended daily dose (500 mg day−1) [16, 33]. The Dixon plot for the inhibition of CYP2C19 in HL8 presented in Figure 2a and further analysis of the parameters of the enzyme inhibition models suggested that the inhibition data fit well to competitive and noncompetitive types of inhibition. Since there was no significant difference between the models, competitive inhibition model was used to calculate the Ki values. Preincubation of a range of TCL concentrations with a NADPH-generating system for 15 and 30 min before the addition of (S)-mephenytoin to the incubation mixture, did not provide any evidence of a mechanism-based inhibitor as the degree of CYPC19 inhibition was comparable with or without preincubations (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Representative Dixon plots for the inhibition of CYP2C19 catalysed (S)-mephenytoin 4-hydroxylation (a) (S)-mephenytoin (µm) • 15, ○ 25, ▴ 35 and ▵ 60) and CYP2D6 catalysed dextromethorphan O-demethylation (b) (dextromethorphan (µm) • 4, ○ 6, ▴ 10, ▵ 20) by ticlopidine (0–40 µm) in HL8. Each point represents averages of duplicate determination.

TCL showed potent inhibition of CYP2D6 catalysed dextromethorphan O-demethylation (Figures 1 and 2b), with a mean Ki value (3.4 µm, n = 3 different HLMs) (Table 1). The representative Dixon plot for the inhibition of CYP2D6 by TCL demonstrated in Figure 2b and parameters of the nonlinear enzyme inhibition models make clear that TCL is a competitive inhibitor of CYP2D6.

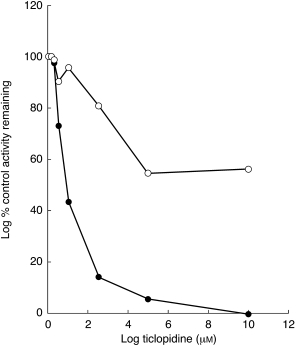

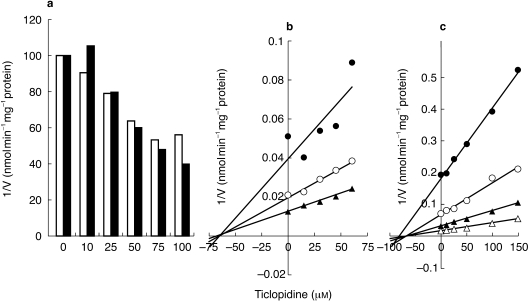

TCL showed moderate inhibition of CYP2C9- catalysed tolbutamide 4-methylhydroxylation (Figure 1). As shown in Figure 3, recombinant human CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 showed catalytic activity towards tolbutamide 4-methylhydroxylation. Consistent with the data from HLMs in Figure 1, TCL preferentially inhibited re-combinant human CYP2C19-mediated tolbuta-mide 4-methylhydroxylation (Ki = 0.184±0.091 µm) relative to that of CYP2C9 catalysed reaction (Ki = 13.2±3.2 µm). Although difference in the Ki for the inhibition of CYP2C9 by TCL was noted in HLMs and recombinant CYP2C9, probably due to changes in the affinity that may partly result from changes in lipid and protein environment in recombinant CYP450 or the contribution of other isoforms in HLMs, TCL was 70 times more potent as an inhibitor of recombinant CYP2C19 relative to that of CYP2C9. TCL (2.5–5 µm) inhibited CYP2C19 by >90%, but inhibition of CYP2C9 was below 15% at these concentrations (Figure 3). These data are consistent with the inhibition of CYP2C19 mediated (S)-mephenytoin 4-hydroxylation by TCL (Figures 1 and 2a) and tolbutamide hydroxylation in HLMs (Figure 1 and Figure 4). The inhibitory potency of TCL on CYP2C9 in HLMs was comparable when tolbutamide or flurbiprofen, a probe that appears to be exclusively catalysed by CYP2C9 with no cross reactivity with other isoforms including CYP2C19 [24], were used (Figure 4). The Ki value (76 µm) derived from three different HLMs for the inhibition by TCL of the CYP2C9 mediated tolbutamide metabolism was slightly lower than that obtained for the inhibition of flurbiprofen 4-hydroxylation (89 µm).

Figure 3.

Recombinant human CYP2C19 (•) and CYP2C9T(○) catalysed tolbutamide methylhydroxylation. The methylhydroxytolbutamide formation rate (pmol min−1 pmol−1 P450) from 50 µm tolbutamide by CYP2C19 or CYP2C9 in the presence of ticlopidine (0–60 µm) was expressed as the percentage of control velocity with no ticlopidine present.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of CYP2C9 mediated tolbutamide 4-methylhydroxylation and flurbiprofen 4′-hydroxylation by ticlopidine (0–150 µm) in HLMs (HL8). Tolbutamide (50 µm,) and flurbiprofen (5 µm,) were incubated with or without ticlopidine in HLMs (a). Representative full Dixon plots for the inhibition by ticlopidine of CYP2C9 mediated tolbutamide hydroxylation (tolbutamide (µm) • 30, ○ 40, ▴ 60) (b) and flurbiprofen hydroxylation (flurbiprofen (µm) • 1, ○ 2.5, ▴ 5, 10) (c) were compared. Each point represents averages of duplicate incubations.

TCL was competitive and moderate inhibitor of CYP1A2 catalysed phenacetin O-deethylation (Figure 1, Table 1), with a mean Ki value from three different HLMs of 49 µm (Table 1) (range: ≈ 30–70 µm), while its effect on the activities of CYP2E1 and CYP3A was marginal.

Discussion

Our in vitro data demonstrated clearly that TCL, at therapeutically relevant concentrations (1–3 µm) [16, 33], is a strong inhibitor of CYP2C19 and CYP2D6. Oxidative metabolism of drugs by the CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 isoforms is a potential source of genetically and drug–drug adverse interactions that have clinical consequences [34, 35]. It is conceivable that TCL may convert extensive metabolizer subjects of these enzymes to phenotypically ‘poor’ metabolizers. If our in vitro data can be extrapolated to the clinic, we would expect that TCL significantly slow the elimination of drugs that are primarily cleared by CYP2C19 and CYP2D6.

The potent inhibition of CYP2C19 by TCL we observed in the present study is consistent with our earlier report [4, 5]. Consistent with this, Tateishi et al. have shown that TCL is a significant inhibitor of CYP2C19 mediated omeprazole 5-hydroxylation in healthy Japanese subjects [11]. Using recombinant human CYP2C19, others [36, 37] have found essentially similar inhibition profile of CYP2C19 (Ki = 0.64 µm or IC50 = 4.5 µm). The clinical relevance of this finding may be best illustrated by examination of the TCL–phenytoin interaction. Phenytoin toxicity as a result of elevated plasma concentrations is the most serious adverse drug interaction described so far in patients taking TCL concomitantly (Table 2). Phenytoin is a prochiral drug that undergoes stereoselective oxidation in humans to form (S)-or (R)-5-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin (p-HPPH), and this pathway contributes to 70–90% of phenytoin elimination [30]. It has been shown that CYP2C9 is the major enzyme metabolizing phenytoin [30] accounting for ≈ 70 % of its in vivo clearance. Besides, CYP2C19, though considered minor, is involved in phenytoin metabolism [38–40]. It appears that the contribution of CYP2C19 is particularly larger at steady-state plasma concentrations of phenytoin (40–80 µm) or higher and it catalyses preferentially the formation of (R)-p-HPPH [32, 40]. The data in the literature, thus, make it clear that both CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 are important in phenytoin metabolism. To examine inhibition of which isoform by TCL is responsible for TCL–phenytoin interaction, selection of a substrate probe reaction that reflects high specificity for each isoform in HLMs containing multiple CYP450s is essential. Tolbutamide methylhydroxylation is a widely used reaction to characterize CYP2C9 [30], but CYP2C19 is also implicated in vitro [31]. That we measured the correct effect of TCL on CYP2C9 is ensured using flurbiprofen as additional specific probe [24]. Our inhibition data from HLMs (Table 1) and recombinant enzymes (Figure 3) have equivocally confirmed preferential inhibition of CYP2C19 by TCL, i.e. TCL is >60–70 times more potent inhibitor of CYP2C19 than CYP2C9. Consistent with this, TCL has been reported to have no influence on the human plasma concentrations of (S)-warfarin [14] and in vitro on diclofenac 4-hydroxylation [37], both specific probes of CYP2C9 [30]. Furthermore, drugs that are potent inhibitors of CYP2C19 (but not of CYP2C9) including omeprazole, felbamate and topiramate [7, 41] have been reported to increase plasma concentrations and/or toxicity of phenytoin. Taken all together, inhibition of CYP2C19 by TCL is the likely mechanism for the increased risk of phenytoin toxicity during TCL coadministration (Table 2). It follows that coadministration of TCL with drugs that are substrates of CYP2C19 (e.g. omeprazole and diazepam) [34, 35] can result in clinically important drug–drug interactions.

Table 2.

Summary of reported metabolic drug interactions during coadministration of ticlopidine*.

| Drug affected | Type of study | Observed effects** [references] | Metabolism of affected drug*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenytoin | Open label | ↑Km and serum levels [5] | CYP2C9, 2C19 |

| Case report and in vitro | ↑Serum levels and toxicity [4] | ||

| Case report | ↑Serum levels and toxicity [8] | ||

| Case report | ↑Serum levels and toxicity [10] | ||

| Case report | ↑Serum levels and toxicity [9] | ||

| Case report | ↑Serum levels and toxicity [6] | ||

| Case report | ↑Serum levels and toxicity [7] | ||

| Carbamazepine | Case report | ↑Serum levels and toxicity [13] | CYP3A, 2C8 |

| Antipyrine | Placebo-controlled | ↑t½ (27%) and AUC (14%) [15] | CYP1A2, 2C9, 3A |

| Theophylline | Placebo-controlled | ↑ t½ (42) and ↓Cl (37%) [12] | CYP1A2, 2E1, 3A |

| R-Warfarin | Open study | ↑Plasma levels (26%) [14] | CYP1A2, 3A, 2C19 |

| S-Warfarin | Open study | No effect [14] | CYP2C9 |

| Omeprazole | Placebo-controlled | ↓5-hydroxylation [11] | CYP2C19 |

| Omeprazole | Placebo-controlled | No effect on sulphone formation [11] | CYP3A |

| Cyclosprin A | Placebo-controlled | No effect [43] | CYP3A |

Onset of interaction, 5 days to 6 weeks after ticlopidine administration

Phenytoin toxicity reported: ataxia, drowsiness, vertigo, gaitdisturbances and leg weakness

reference [1].

Our in vitro data in HLMs clearly demonstrate that TCL is a strong inhibitor of CYP2D6 (Ki < 4 µm). Using recombinant human CYP2D6-catalysed probe reactions, other authors [36, 37] have reported that TCL is a potent inhibitor of this isoform (Ki = 0.4 µm and IC50 = 3.5 µm). However, we have found no in vivo evidence in the literature that TCL affects the elimination of drugs that are CYP2D6 substrates (see Table 2). In view of the serious adverse drug interactions that may result from inhibition of CYP2D6 and the low Ki value we found in the present study, the inhibition of CYP2D6 by TCL needs to be tested under clinical settings using pertinent in vivo probes for CYP2D6.

That TCL might inhibit CYP1A2 is suspected from its ability to alter significantly the pharmacokinetics of CYP1A2 substrate drugs including theophylline [12], antipyrine [14] and R-warfarin [15] (see also Table 2). Our findings in which the Ki value (49 µm) was found to be >10 times higher than the therapeutic plasma concentration of TCL [16, 32] do not provide definitive mechanism for the TCL-CYP1A2 substrate drug interactions reported (Table 2). The inhibition of CYP1A2 in vitro varied greatly in the livers we studied, raising the possibility of variable magnitude of pharmacokinetic interaction between TCL and CYP1A2 substrates. Of note, TCL accumulates in rat liver [16] and if this can be extrapolated to humans, there may be subsets of patients (e.g. cigarette smokers), who are particularly vulnerable to TCL drug interactions, as is the case with the ciprofloxacin–theophylline interaction [42].

TCL is unlikely to alter the pharmacokinetics of CYP3A and CYP2E1 substrate drugs. TCL has been reported to increase the plasma concentrations of carbamazepine [13], a drug whose major metabolic pathway is catalysed by CYP3A [41]. However, the results of the present study and given that TCL had little effect on the plasma concentrations of cyclosporin A [43] as well as the CYP3A mediated omeprazole sulphone formation [11] do not support that CYP3A mediated inhibition is involved. Other enzymes (e.g. CYP2C8) might play important roles in carbamazepine metabolism [41].

We have provided the first comprehensive in vitro data that enable us to understand and predict drug interactions with TCL. This drug is a potent in vitro inhibitor of CYP2C19 that has demonstrable clinical consequences. Although our findings suggest that TCL is also a potent CYP2D6 inhibitor, this observation deserves further clinical confirmation as many important drugs (e.g. antidepressants, antiarrhythmics and neuroleptics) depend on the activity of CYP2D6 for their elimination. The use of TCL is limited owing to its potential to produce haematotoxicity [44]. Nevertheless, it is still an important alternative for patients who are intolerant to aspirin [4] or who receive coronary stents [45, 46]. A considerable accumulation of TCL has been reported in patients plasma during repeated dosing relative to single dose administration: prolonging half-life from ≈ 8 h to up to 96 h and resulting in a 3.7-fold accumulation ratio [15, 16, 32]. These data have implications for the metabolism of ticlopidine itself. It is possible that the metabolism of TCL, like phenytoin, is saturable and may depend on genetically polymorphic enzymes. Our data, together with knowledge of factors that contribute to the alteration of TCL disposition and increase the risk of adverse drug interactions, should enable physicians to prescribe ticlopidine in a more rational, safe and effective manner.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a Shannon Director's award (DAF) R55-GM56898, and by grants R01-GM56898-01 and T32-9M08386 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Bethesda, MD.

References

- 1.Bertz RJ, Granneman GR. Use of in vitro and in vivo data to estimate the likelihood of metabolic pharmacokinetic interactions. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:210–258. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199732030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin HJ, Lu AYH. Inhibition and induction of cytochrome P450 and the clinical implication. Clin Pharmacokin. 1998;35:362–390. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199835050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McTavish D, Faulds D, Goa KL. Ticlopidine: an update review of its pharmacology and therapeutic use in platelet dependent disorders. Drugs. 1990;40:238–259. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199040020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donahue SR, Flockhart DA, Abernethy DR, Ko J-W. Ticlopidine inhibition of phenytoin metabolism mediated by potent inhibition of CYP2C19. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1997;62:572–577. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donahue SR, Abernethy DR. Ticlopidine inhibition of steady state phenytoin metabolism in humans (abstract) Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;63:183. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(97)90054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez-ariztegui N, Ochoa Sanchez-migallon MJ, Nevado C, Martin M. Intoxicacion aguda por fenitoina secundaria a interaccion con ticlopidina. Rev Neurol. 1998;26:1017–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klaassen SL. Ticlopidine-induced toxicity. Ann Pharmacother. 1998;32:1295–1298. doi: 10.1345/aph.17296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Privitera M, Welty TE. Acute phenytoin toxicity followed by seizure breakthrough from a ticlopidine–phenytoin interaction. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:1191–1192. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550110143027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rindone JP, Bryan GII, Ariz P. Phenytoin toxicity associated with ticlopidine administration [letter] Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riva R, Cerullo A, Albani F, Baruzzi A. Ticlopidine impairs phenytoin clearance; a case report. Neurology. 1996;46:1172–1173. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tateishi T, Kumai T, Watanabe M, Nakura H, Tanaka M, Kobayashi S. Ticlopidine decreases the in vitro activity of CYP2C19 as measured by omeprazole metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47:454–457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colli A, Buccino G, Cocciolo M, Parravivini R, Elli GM, Scaltrini G. Ticlopidine–theophylline interaction. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1987;41:358–362. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1987.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown RI, Cooper TG. Ticlopidine–carbamazepine interaction in a coronary stent patient. Can J Cardiol. 1997;13:853–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gidal BE, Sorkness CA, McGill KA, Larson R, Levine RR. Evaluation of a potential enantioselective interaction between ticlopidine and warfarin in chronically anticoagulated patients. Ther Drug Monit. 1995;17:33–38. doi: 10.1097/00007691-199502000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudsen JB, Bastain W, Sefton CM, Allen JG, Dickinson JP. Pharmacokinetics of ticlopidine during chronic oral administration to healthy volunteers and its effects on antipyrine pharmacokinetics. Xenobiotica. 1992;22:579–589. doi: 10.3109/00498259209053121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desager JP. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ticlopidine. Clin Pharmacokin. 1994;26:347–355. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199426050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray JC, Kelly MA, Gorelick PB. Ticlopidine: a new antiplatelet agent for the secondary prevention of stroke. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1994;17:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris JW, Rahman A, Kim BR, Guengerich FP, Collins JM. Metabolism of taxol by human hepatic microsomes and liver slices: participation of cytochrome P4503A4 and an unknown P450 enzyme. Cancer Res. 1994;54:4026–4035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard HB, Menard R, Brabdt HA, Pazolzs CJ, Creutz CE, Ramu A. Application of Bradford's assay to adrenal gland subcellular fractions. Anal Biochem. 1978;86:761–763. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90805-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desta Z, Kerbusch T, Soukhova N, Richard E, Ko JW, Flockhart DA. Identification and characterization of human cytochrome P450 isoforms interacting with pimozide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285:428–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ko J-W, Soukhova N, Thacker D, Chen P, Flockhart DA. Evaluation of omeprazole and Lansoprazole as inhibitors of cytochrome P450 isoforms. Drug Metab Dispos. 1997;25:853–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tassaneeyakul W, Birkett DJ, Veronese ME, et al. Specificity of substrate and inhibitor probes for human cytochrome P450 1A1 and 1A2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Relling MV, Aoyama T, Gonzalez FJ, Meyer UA. Tolbutamide and mephenytoin hydroxylation by human cytochrome P450s in the CYP2C subfamily. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1990;252:442–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tracy TS, Marra C, Wrighton SA, Gonzalez FJ, Korzekwa KR. Studies of flurbiprofen 4′hydroxylation: additional evidence suggesting the sole involvement of cytochrome P450 2C9. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1305–1309. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wrighton SA, Stevens JC, Becker GW, VandenBranden M. Isolation and characterization of human liver cytochrome P4502C19: correlation between 2C19 and S-mephenytoin 4′-hydroxylation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;306:240–245. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broly F, Libersa C, Lhermitte M, Bechtel P, Dupuis B. Effect of quinidine on the dextromethorphan O-demethylase activity of microsomal fractions from human liver. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;28:29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb03502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thummel KE, Shen DD, Podoll TD, et al. Use of midazolam as a human cytochrome P450, 3A probe: I. In vitro–in vivo correlations in liver transplant patients. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gorski JC, Jones DR, Wrighton SA, Hall SD. Characterization of dextromethorphan N-demethylation by human liver microsomes. Contribution of the cytochrome P4503A (CYP3A) subfamily. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;48:173–182. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90237-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peter R, Bocker R, Beaune PH, Iwaski M, Guengerich FP, Xang CS. Hydroxylation of chloroxazone as a specific probe of cytochrome P450IIE1. Chem Res Toxicol. 1990;3:566–573. doi: 10.1021/tx00018a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miners JO, Birkett DJ. Cytochrome P4502C9: an enzyme of major importance in drug metabolism. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;45:525–538. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1998.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lasker JM, Wester MR, Aramsombatdee E, Raucy JL. Characterization of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 from human liver: respective roles in microsomal tolbutamide, S-mephenytoin, and omeprazole hydroxylations. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;353:16–28. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bajpai M, Roskos LK, Shen DD, Levy RH. Roles of cytochrome P4502C9 and cytochrome P4502C19 in the stereoselective metabolism of phenytoin to its major metabolite. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996;24:1401–1403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah J, Teitelbaum P, Molony B, Gabuzda T, Massey I. Single and multiple dose pharmacokinetics of ticlopidine in young and elderly subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32:761–764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flockhart DA. Drug interactions and the cytochrome P450 system: the role of cytochrome P4502C19. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29(Suppl 1):45–52. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199500291-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertilsson L. Geographical/interracial differences in polymorphic drug oxidation. Current state of knowledge of cytochromes P450(CYP) 2D6 and 2C19. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;29:192–209. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199529030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mankowski DC. The role of CYP2C19 in the metabolism of (+/-) bufuralol, the prototypic substrate of CYP2D6. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1024–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masimirembwa CM, Otter C, Berg M, et al. Heterologous expression and kinetic characterization of human cytochromes P450: Validation of a pharmaceut tool for drug metabolism research. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1117–1122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yasumori T, Chen L, Li Q, et al. Human CYP2C-mediated stereoselective phenytoin hydroxylation in Japanese: difference in chiral preference of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;57:1297–1303. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fritz S, Lindner W, Roots I, Frey BM, Kupfer A. Stereochemistry of aromatic phenytoin hydroxylation in various drug hydroxylation phenotypes in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1987;241:615–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mamiya K, Ieiri I, Shimamoto J, et al. The effect of genetic polymorphisms of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 on phenytoin metabolism in Japanese adult patients with epilepsy: studies in stereoselective hydroxylation and population pharmacokinetics. Epilepsia. 1998;39:1317–1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levy RH. Cytochrome P450 isoenzymes and antiepileptic drug interactions. Epilepsia. 1995;36(Suppl 5):S8–S13. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb06007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Betty KT, Davis TM, Ilett KF, Dusci LJ, Langton SR. The effect of ciprofloxacin on theophylline pharmacokinetics in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;39:305–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1995.tb04453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Boissonnat P, Lorgeril M, Perroux V, et al. A drug interaction study between ticlopidine and cyclosporin in heart transplant recipients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;53:39–45. doi: 10.1007/s002280050334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Love BB, Biller J, Gent M. Adverse haematological effects of ticlopidine. Drug Safety. 1998;19:89–98. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199819020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisberg LA. The efficacy and safety of ticlopidine and aspirin in non-whites: analysis of a patient subgroup from the Ticlopidine Aspirin Stroke Study. Neurology. 1993;43:27–31. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leon MB, Baim DS, Popma JJ, et al. A clinical trial comparing three antithrombotic-drug regimens after coronary-artery stenting. Stent Anticoagulant Restenosis Study Investigation. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1665–1671. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199812033392303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]