Abstract

Aims

To investigate potential interactions between reviparin and acetylsalicylic acid (ASA 300 mg o.d. from day 1–5).

Methods

In an open, randomized, three-way-cross over study nine healthy volunteers received reviparin (s.c. injection of 6300 anti-Xa units) or placebo from days 3 to 5 and acetylsalicylic acid (ASA 300 mg) or placebo from days 1 to 5. Assessments included bleeding time (BT), collagen (1 µg ml−1) induced platelet aggregation (CAG), heptest, plasma antifactor Xa-activity and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT).

Results

Median bleeding time at day 5 was 5.5 min after reverparin alone and after ASA alone and was 9.6 min after the combination of reviparin and ASA. ASA treatment reduced CAG from 84% to 40 to 50% of Amax; values after combined treatment of reviparin with ASA were not different from those after ASA alone. aPTT was prolonged to 32 s after reviparin; this effect was not modified if subjects received ASA. Combined treatment with ASA and reviparin had no effect on plasma anti-Xa-activity and heptest compared with reviparin alone.

Conclusions

We could not entirely exclude a small interaction between reviparin and ASA on bleeding time, but the effect is probably without clinical significance.

Keywords: ASA-interaction, bleeding time, reviparin

Introduction

The combination of the antiplatelet drug acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and the antithrombin heparin is a useful therapeutic strategy, e.g. after MI or revasculariza- tion procedures [1–3]. Low-molecular-weight-heparins (LMWHs) have recently shown potential clinical advantages over unfractionated heparins (UFH) in unstable angina or percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty [4, 5]. One rationale for the combination of ASA with heparin is that after platelet activation, the platelet surface serves as a pivotal site for assembly of the prothrombinase-complex. Platelet activation therefore can be viewed as a thrombin-generating system that contributes to an increase in local thrombin concentration, and inhibition of platelet activation might have additive effects on heparin activity. Nevertheless, this interaction might also increase bleeding risks, and greater than additive effects with ASA on skin bleeding time has been described with UFH [6–8]. However, similar findings have been reported only inconsistently with LMWH or heparinoids [7–9]. On the other hand, UFH itself might provoke enhanced platelet aggregation, although the clinical relevance of this phenomenon is unclear [10].

Our study was performed to assess the pharmaco-dynamic interaction between the LMWH reviparin and ASA. Reviparin is prepared from porcine intestinal mucosa by nitrous acid depolymerization [11]. It has a mean molecular weight of 3.900 Da (range 3.500–4.500) and shows a ratio of antiXa/anti-IIa activity > 3.6 [11]. The pharmacological profile of reviparin resembles that of enoxaparin [12]. Doses established for clinical indications (DVT prophylaxis, unstable angina) are between 4200 and 6300 U day−1 [5, 13, 14]. The effects of reviparin and ASA given alone on primary haemostasis, platelet function and coagulation were compared with those of their combined application in nine healthy volunteers in a double-blind, randomised, three-way-cross-over design.

Methods

In nine healthy volunteers (four women, five men, aged 21–36 years) reviparin (6300 anti-Xa units o.d., Batch Nr. LU097–43, Knoll AG, Germany) or placebo was administered subcutaneously from day 3–5 with or without concomitant application of oral ASA (300 mg once daily, Bayer AG, Germany) or placebo from day 1–5 in a randomized three period (ASA + s.c. placebo, reviparin + p.o. placebo, ASA + reviparin) cross-over design with wash-out periods of 14 days between each period. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board, and study subjects gave their written informed consent.

Sampling protocol

Bleeding time (BT) was assessed prior (0 h) to administration on days 1 and 5. Blood samples for the analysis of anti-Xa activity, heptest and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) were collected prior to application (0 h) on days 1, 3, 4 and 5 and at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24 h after injection on day 3 and 5. For platelet count and collagen induced platelet aggregation (CAG) blood was taken before administration (0 h) on day 1, 3 and 5.

Blood was collected from the brachial vein in 3.13% sodium citrate 9 : 1 for anti-Xa, aPTT and CAG. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) was prepared within 30 min by centrifugation at 150 g for 3 min at room temperature. Samples for the coagulation tests were centrifuged immediately after withdrawal at 2.000 g for 10 min. The supernant platelet poor plasma (PPP) was stored at −80 °C until assayed.

Assessments

Bleeding times (BT) were measured in the forearm by using a sphygomanometer cuff inflated to 40 mmHg in the upper arm. A standardized horizontal laceration (5 mm long and 1 mm deep) was created on the anterior surface of the forearm by using a Simplate® device (Organon, FRG) and the BT was determined according to the manufacturer's directions. Blood was removed from the cut with filter paper after 15 s and then at 15 s intervals until the bleeding had stopped, at which point the time was recorded (normal range 4–10 min) [15].

Collagen induced platelet aggregation [16] was measured turbidimetric on an automated aggregation clotting timer (Fa. Laborgeräte und Analysensysteme, Ahrensburg, Germany) using collagen (1 µg ml−1 final concentration, Nycomed Amersham GmbH, Germany) as inducer. PRP used for the aggregation test was not prediluted with PPP.

Platelet count in whole blood was performed using a cell counter (Sysmex GmbH, Germany).

Anti-Xa activitiy was determined using Coatest Heparin (Chromogenics). The results are expressed in anti-Xa units. Bioavailability of reviparin was estimated by analysis of the time courses of plasma anti-Xa levels. For each subject the area under the concentration/activity vs time curve (AUC(0,24 h)) was calculated at day 3 and day 5 using the trapeziodal rule.

Heptest is a clotting assay that is sensitive to both anti-Xa and anti-IIa activity, as well as inhibition of the extrinsic pathway by LMWH-stimulated release of tissue factor pathway inhibitor [17]. Heptest was determined in seconds by a ACL 300 R analyser (Instrumentation Laboratory).

Activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) was determined by an aPTT ellagic acid device (Instrumentation Laboratory).

Statistics

Results of BT and CAG were analysed exploratively by the Mann–Whitney U-test for difference between baseline (day 1) and treatment (day 3 or 5) as well as for difference between treatment (e.g. day 5 combination vs day 5 either drug alone). Nonparametric 95% confidence intervals and point estimates were calculated for the difference between treatments at day 5. All other parameters are presented descriptively by mean and s.d.

Results

Tolerability

The study medication was well tolerated by all volunteers. No adverse event occurred throughout the study, and platelet counts were not affected by either treatment.

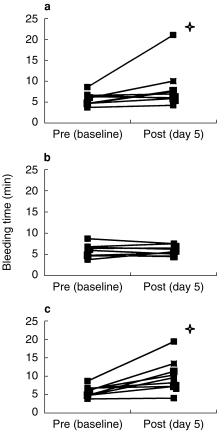

Bleeding time

ASA and reviparin treatment alone did not affect bleeding time significantly although one volunteer showed a prolongation of bleeding time from 8.3. to 23.0 min after ingestion of ASA over 5 days (Figure 1). A slight prolongation of median BT from 5.4 to 9.6 min was observed after the combination of reviparin and ASA at day 5 with a P value of < 0.01 compared with pretreatment and P < 0.05 compared with treatment with both drugs (95% confidence interval for reviparin + ASA vs reviparin alone −0.3+ 11.4 min, point estimate 4.1 min) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Template bleeding times (min) prior to drug application at day 1 and 5. (a). ASA alone 300 mg once daily from day 1–5, (b). Reviparin 6300 anti-Xa-units once daily. from day 3–5 and (c). ASA 300 mg once daily.and reviparin 6300 anti-Xa-units once daily from day 3–5. Star indicates same subject.

Table 1.

Bleeding time (min) (median and range) and collagen (1 µg ml−1) induced aggregation in percentage (mean ± s.d., n = 9) after 6300 U day−1 reviparin (REV) + placebo (P), 300 mg day−1 aspirin (ASA) + placebo and combination reviparin + aspirin

| Day 1 (baseline) | Day 3 pre dose | Day 5 pre dose | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bleeding time | REV + P | 5.1 (3.3–9.5) | 5.5 (3.1–9.2) | |

| ASA + P | 5.1 (3.5–8.6) | 5.5 (4.4–23.0) | ||

| ASA + REV | 5.4 (3.5–8.1) | 9.6 (4.0–19.5)*# | ||

| Collagen induced aggregation | REV + P | 82 ± 7 | 82 ± 11 | 88 ± 4 |

| ASA + P | 84 ± 5 | 50 ± 20* | 43 ± 20* | |

| REV + ASA | 85 ± 5 | 46 ± 18* | 39 ± 16* |

P < 0.01 vs day 1

P < 0.05 vs REV + P.

| Bleeding time (min) | Aggregation (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | PE | CI | PE | |

| REV + P vs ASA + P | −3.0 – + 7.3 | + 1.4 | −79–29 | −48 |

| REV + ASA vs ASA + P | −1.5 – + 3.8 | + 0.7 | −18 – + 26 | + 2 |

| REV + ASA vs REV + P | −0.3 – + 11.4 | + 4.1 | −82–37 | −48 |

Platelet function

ASA treatment reduced collagen (1 µg ml−1) -induced platelet aggregation from 84% to 40 to 50% of maximal aggregation at day 3 as well as at day 5, but values after combined treatment of reviparin with ASA were not different from those after ASA alone (95% confidence interval for reviparin + ASA vs ASA alone at day 5 −18, + 26%, point estimate 2%) (Table 1).

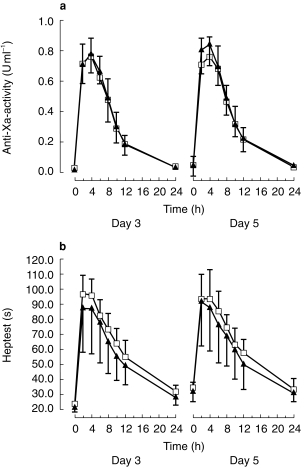

Activated partial thromboplastin time, heptest and anti-Xa-activity

After reviparin alone, aPTT was prolonged from 24 s at baseline to a maximum of 32 s at day 3 as well as at day 5. This effect was not modified if subjects received ASA. Combined treatment with ASA had no effect on plasma anti-Xa-activity under reviparin (Figure 2). The AUC(0,24 h) at day 5 was 8.06 ± 1.22 U ml−1 h after reviparin alone, compared with 7.52 ± 1.92 U ml−1 h after ASA comedication. The difference was not significant. Heptest was 23 s at day 3 predrug and was prolonged at day 5 prior to drug administration to 34 s when reviparin was given alone and 32 s after reviparin and ASA (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

(a) Anti-Xa-activity (U ml−1) after repeated doses of reviparin (6300 anti-Xa-units once daily from day 3–5) with (▴) or without (□) concomitant application of ASA (300 mg once daily from day 1–5). (b) Heptest (s) after repeated doses of reviparin (6300 anti-Xa-units once daily from day 3–5) with (▴) or without (□) concomitant application of ASA (300 mg once daily from day 1–5).

Discussion

The principal findings of this interaction study in healthy subjects were (1) bleeding times after ASA tended to be somewhat more pronounced when combined with reviparin, (2) reviparin did not influence the inhibiting effects of ASA on platelet function as evaluated by collagen-induced platelet aggregation, and (3) no interactions were observed for aPTT, heptest and plasma anti Xa-activity. aPTT values were prolonged 1.5-fold, providing evidence for a therapeutic effect of reviparin during our study.

Prolongation of bleeding time after ASA or heparins alone has been reported inconsistently [7, 8, 18]. There are several reports of possible interaction between ASA and heparins. Bang et al. [6] investigated the influence of ASA, the LMWH enoxaparin (intravenous infusion of 75 anti-Xa-U kg−1 10 min before ASA) and UFH on bleeding time. ASA alone (1.5 g single dose) did not prolong bleeding time 1 h after ingestion but in combination with both heparins bleeding time was considerably prolonged two to threefold. Mikhailidis et al. [7] observed a slight prolongation of bleeding time after the combination of both UFH or the LMW-heparinoid Org 10172 with ASA which was not seen with ASA or the different heparins alone. In contrast to our results, de Boer et al. [8] observed markedly prolonged bleeding times after 2 × 500 mg ASA alone (14 min) and the combined treatment with Org 10172 15 min after injection (20 min). Bleeding time tended to be more prolonged after the combination. Also thrombin time was prolonged to a greater extent after Org 10172 + ASA than after Org 10172 or ASA alone, supporting a potential (but probably clinically not significant) interaction between both drugs. Prolonged bleeding times during ASA alone and the combined treatment did not correspond with a stronger inhibition of collagen-induced platelet aggregation. In all of these studies ASA appeared to be associated with a modest increase in bleeding time only in some of the subjects, suggesting variability in response to ASA. On the other hand, variations in the performance of bleeding time assessment (direction of skin cuts and depth of incisions) might explain differences in bleeding time results throughout the studies [18–20]. Finally different treatment allocations and varying doses of ASA and heparins administered throughout the studies have to be considered.

We found that the inhibiting effect of ASA on platelet function as evaluated by collagen induced platelet aggregation was unaffected by reviparin, since aggregation after combined treatment was not different from ASA alone. Conflicting data have been reported by other investigators [7, 8, 21]. De Boer et al. [8] found that inhibiting effects of ASA on platelet function were not influenced by the LMW heparinoid Org 10172. Mean EC50 values for collagen induced platelet aggregation during combined treatment with ASA + Org 10172 averaged 3.4 ng ml−1 collagen and were not statistically different from values during ASA treatment alone (3.75 ng ml−1) 90 min after injection. The platelet aggregatory effect of conventional UFH and LMWH was investigated by Chen et al. [21] with whole blood aggregometry an collagen (1 µg ml−1) as activator. In contrast to our results both UFH and LMWH stimulated platelet aggregation before and after ASA ingestion (500 mg single dose). This pro-aggregatory effect was not inhibited by RGD-peptides binding at the GPIIb/IIIa-receptor, implying platelet activation via a ‘nonspecific’ mechanism.

In conclusion there appeared to be no clinically relevant interaction between reviparin and ASA in this study at the level of primary haemostasis, platelet function and blood coagulation. Bleeding time tended to be somewhat more pronounced after combination of the drugs. We could not entirely exclude a small interaction between reviparin and ASA, but these effects are probably without clinical significance. This conclusion is supported by clinical data on reviparin in coronary patients after percutanous angioplasty [22], where the rate of major bleeding events after reviparin/ASA (2.5%) was not different from that after ASA alone (2.6%).

References

- 1.Schwartz L, Bourassa MG, Lesperance J, et al. Aspirin and dipyridamole in the prevention of restenosis after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1714–1719. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198806303182603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dyken ML, Vokonas PS, Hennekens C. Members (Special Writing Group Fuster V). Aspirin as a therapeutic agent in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1993;87:659–675. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.2.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viinikka L. Acetylsalicylic acid and the balance between prostacyclin and thromboxane A2. Scand J Lab Invest. 1990;50(Suppl 201):103–108. doi: 10.3109/00365519009085806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turpie AG. Low-molecular-weight heparins and unstable angina-current perspectives. Haemostasis. 1997;27:19–24. doi: 10.1159/000217478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preisack MB, Bonan R, Meisner C, Eschenfelder V, Karsch KR. on behalf of the REDUCE study group. Incidence, outcome and prediction of early clinical events following percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:1232–1238. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1998.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bang CJ, Riedel B, Talstad I, Berstad A. Interaction between heparin and acetylsalicylic acid on gastric mucosal and skin bleeding in humans. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27:489–449. doi: 10.3109/00365529209000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikhailidis DP, Fonseca VA, Barraddas MA, Jeremy JY, Dandona P. Platelet activation following intravenous injection of a conventional heparin: absence of effect with low molecular weight heparinoid (Org 10172) Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;24:415–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Boer A, Danhof M, Cohen AF, Magnani HN, Breimer DD. Interaction study between Org 10172, a low molecular weight heparinoid, and acetylsalicylic acid in healthy male volunteers. Thromb Haemost. 1991;61:202–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter CJ, Kelton JG, Hirsh J, Cerskus AL, Santos AV, Gent M. The relationship between the haemorrhagic and antithrombotic properties of low molecular weight heparins and heparin. Blood. 1239;59:1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao Z, Théroux P. Platelet activation with unfractionated heparin at therapeutic concentrations and comparison with a low-molecular-weight heparin and with a direct thrombin inhibitor. Circulation. 1998;97:251–256. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeske W, Fareed J, Eschenfelder V, Iqbal O, Hoppensteadt D, Ahsan A. Biochemical and pharmacologic characteristics of Reviparin, a low-molecular-mass heparin. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1997;23:119–128. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-996079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Azizi M, Veyssier-belot C, Alhenc-gelas M, et al. Comparison of biological activities of two low molecular weight heparins in 10 healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;40:577–584. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boneu B. An international multicenter study: reviparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing general surgery. Blood Coagulation Fibrinolysis. 1993;4:21–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Planes A, Chastang C, Vochelle N, Desmichels D, Alach M, Fiessinger JN. Comparison of of antithrombotic efficacy and haemorrhagic side-effects of reviparin-sodium versus enoxiparin in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Blood Coagulation Fibrinolysis. 1993;4:33–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mielke CH, Kaneshire MM, Maher IA. The standardized normal Ivy bleeding time is prolongation by aspirin. Blood. 1969;34:204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Born GVR. Quantitative investigation into the aggregation of blood platelets. J Physiol. 178:67–68. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abbate R, Gori AM, Farsi A, Attanasio M, Pepe G. Monitoring of low-molecular-weight heparins in cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00111-8. L L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bode-böger SM, Böger RH, Schubert M, Frölich JC. Effects of very low dose and enteric-coated acetylsalicylic acid on prostacyclin and thromboxane formation and on bleeding time in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;543:707–714. doi: 10.1007/s002280050539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuman R, Ansell JE, Canoso RT, Deykin D. Clinical trials of a new bleeding time device. Am J Clin Path. 1978;70:642–645. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/70.4.642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Czapek EE, Deykin D, Salzman E, Lian E, Hellerstein LJ, Rosoff CB. Intermediate syndrome of platelet dysfunction. Blood. 1978;52:103–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J, Karlberg KE, Sylvén C. Heparin and low molecular weight heparin but not hirudin stimulate platelet aggregation in whole blood from acetylsalicylic acid treated healthy volunteers. Thromb Res. 1991;63:319–329. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(91)90135-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karsch KR, Preisack MB, Baildon R, et al. Low molecular weight heparin (reviparin) in percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Results of a randomized,double-blind, unfractionated heparin and placebo-controlled, multicenter trial (REDUCE trial) Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:1437–1443. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00343-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]