Abstract

Aims

The aim of this investigation was to compare the effects of standard (S) with low molecular weight (LMW) heparin on circulating levels of heparin-binding growth factors (HBGF), known to have angiogenic properties in humans.

Methods

In two consecutive trials 18 healthy male voluteers were studied on three separate occasions, following a placebo-controlled crossover design. Subjects were randomised to receive either S-heparin or LMW heparin or placebo. Heparins were administered either by intravenous (i.v.) or subcutaneous (s.c.) injection and saline placebo by i.v. injection. Serum concentrations of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) were measured before and up to 24 h after injection.

Results

Administration of i.v. S-or LMW-heparin (50 IU kg−1) resulted in rapid, highly significant (47 fold for S, 30.9 fold for LMW) increases in HGF serum values, reaching maxima of 10.51 ± 1.65 ng ml−1 (S) and 8.28 ± 1.04 ng ml−1 (LMW), respectively, 10 min after drug application. S.c. injection of S-heparin or LMW heparin resulted in 4.1 and 5.4 fold increases in HGF serum values, respectively. Both agents showed no effects on circulating VEGF or bFGF levels, independent of the route of administration.

Conclusions

Circulating HGF levels were selectively increased in response to pharmacological doses of two, widely used heparin preparations. This may, in part, explain some of the biological effects of heparin separate from its anticoagulant properties. By this mechanism, the systemic administration of heparin may facilitate collateral vessel formation in various clinical settings of tissue ischaemia.

Keywords: angiogenesis, healthy subjects, hepatocyte growth factor, low molecular weight heparin, standard heparin

Introduction

Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) is a well characterized growth factor [1] and considered to be a principal mediator of mesenchymal-epithelial/endothelial interactions contributing to embryogenesis, organ regeneration, wound healing, and angiogenesis [2]. The HGF receptor has been identified as the c-met proto-oncogene product, a transmembrane tyrosine kinase [2]. Previous studies have established that HGF directly stimulates proliferation and migration of cultured endothelial cells, promotes development of capillary like structures in vitro and stimulates blood vessel formation in Matrigel plugs and normal cornea also in vivo[3–5].

HGF expression is increased in animal models of liver and kidney injury, and exogenous administration of HGF leads to growth promoting effects [6], thus facilitating repair after organ damage [7, 8]. Evidence for a role of HGF in the cardiovascular system comes from studies demonstrating elevated levels of circulating HGF in hypertensive subjects [9] as well as in the early stages of acute myocardial infarction [10]. Results by Ono provide evidence that the HGF/c-met system plays an important role in capillary endothelial cell regeneration in the ischaemically injured heart [11].

Besides HGF [5], several other heparin binding growth factors (HBGFs) such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [12], and fibroblast growth factors (FGF-5 and bFGF) [13] have been shown to induce angiogenesis in animal models of limb or myocardial ischaemia as well as in humans [14]. HBGFs and HGF have a high affinity to heparin and other heparin sulphate proteoglycans abundantly expressed in vivo[15, 16]. Heparin also interacts with circulating HGF levels in animal models and in humans [8, 17, 18, 37].

On the basis of the given interactions of heparins with HBGFs [15], we studied the influence of two therapeutically used heparin preparations on the serum levels of three HBGFs with well characterized angiogenic properties. In order to avoid any disease related effects, the study was performed in healthy subjects.

Methods

Materials

S-heparin (Liquemin®, heparin-Na, Hoffmann-La Roche Grenzach-Whylen, Germany) and LMW-heparin (Fragmin®, dalteparin, Pharmacia & Upjohn GmbH, Erlangen, Germany) are commercially available preparations. Heparinase I was purchased from Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany. ELISA kits for determination of bFGF, VEGF and HGF serum concentrations were purchased from R & D Systems Inc. Minneapolis, USA.

Subjects

Eighteen healthy male volunteers with a mean age of 27.2 ± 3.6 years, a mean body weight of 76.5 ± 10.55 kg and a height of 177 ± 7.9 cm (body mass index 24.11 ± 1.96 kg m−2) in the standard heparin group and 29.2 ± 4.1 years, 80.6 ± 10.5 kg, 181 ± 4.7 cm (body mass index 24.60 ± 1.73 kg m−2), respectively, in the LMW-heparin group were included in the trial. All subjects gave informed written consent prior to entry into the study. Criteria for selection of volunteers were the absence of any regular medication, no history of allergy or drug abuse, and the absence of any acute or chronic disease. Subjects refrained from alcohol, tobacco and caffeine for at least 24 h prior to administration of the study medication. Good general health was diagnosed by means of a thorough clinical examination, including medical history, physical examination, normal ECG and standard clinical laboratory tests. The protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Heidelberg.

Study protocols

The two investigations were designed as separate, prospective, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover studies. Subjects were divided into two groups. One group received either 50 IU kg−1 body weight (BW) S-heparin (Liquemin®) i.v. (dissolved in 5 ml saline) or s.c. (1 ml) or placebo (5 ml saline i.v.), on one of the three study dates, according to the randomization protocol. The other group received either 50 IU kg−1 BW LMW-heparin or placebo following an identical protocol. Study days in each group were separated by a drug free interval of at least 6 days. I.v. injections were performed using a 20 gauge plastic cannula (Abbocath® T.Abbott, Ireland LTD) inserted into a large antecubital vein of one arm. Blood samples were withdrawn from a plastic cannula inserted into the contralateral forearm, before administration of study medication and 10 min, 20 min, 40 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h thereafter. Blood samples were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min at 4 °C and stored for analysis at −25 °C. samples were analysed within 4 weeks.

Measurements of bFGF, HGF and VEGF

Concentrations of bFGF, HGF and VEGF were determined from frozen (−25 °C) serum samples by commercially available monoclonal antibody-based ELISA assays (R & D Systems, Inc. Minneapolis, USA). Individual samples were digested with heparinase I prior to the assay, however, there was no differences between heparinase digested and untreated samples with respect of bFGF, VEGF or HGF values. All samples were measured in duplicate.

Statistical analysis

Area under the curve values of HGF were assessed as incremental area over individual baseline and were calculated for 0 h−24 h (AUC(0,24 h) and expressed as pg ml−1 24 h using SAS/Stat software® version 6.07 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Serum concentrations of HBGFs and AUC(0,24 h) values were expressed as mean ± s.d.. Comparisons between values were made by unpaired Student's t-test and P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

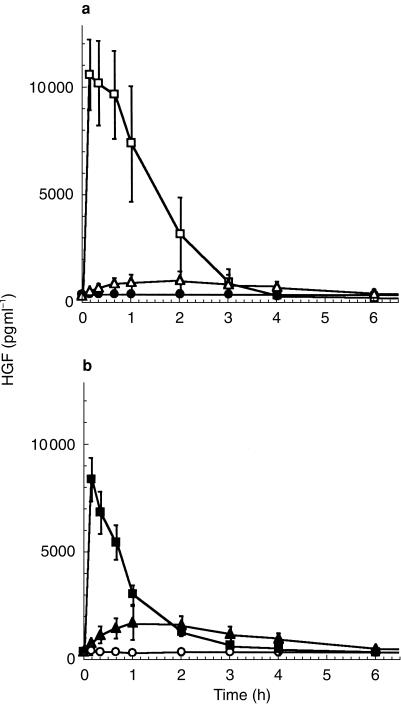

Intravenous injection of S-heparin into healthy individuals induced a rapid increase in circulating HGF levels from 223.7 ± 81 pg ml−1 (95%CI:161.44–285.96) before injection up to 10515.9 ± 1658 pg ml−1 (95%CI:9240.55–11789) 10 min after injection (P < 0.0001). S.c. application of S-heparin induced a much slower rate of increase, only reaching maximum circulating HGF levels of 973.7 ± 43 pg ml−1 (4.1 fold above baseline; 95%CI:940.65–1006.75) after 2 h (Figure 1a, and Table 1). Significant (P < 0,0001) elevations above baseline were observed after 10 min for both forms of application, however. HGF concentrations remained elevated, for 3 h following i.v. administration and for 4 h following s.c. administration. Comparison of AUC(0,24 h) values in the S-heparin group revealed significant differences (Table 2) between i.v. and s.c. application (P < 0.0001).

Figure 1.

Profiles of the mean serum concentration over time for circulating HGF in human subjects following a single dose of either 50 IU kg−1 body weight S-heparin (a) administered i.v. (□), s.c. (▵) or placebo i.v. (•), or (b) LMW-heparin administered either i.v. (▪) or s.c. (▴) or placebo i.v. (○). Results are expressed as mean ± 1 s.d.

Table 1.

Pharmacokinetic data.

| Detection limit of assay | Concentration in untreated subjects | Change in response | Change in response to i.v. S-heparin | Change in response to s.c. heparin | Change in response to i.v. LMW heparin | to s.c. LMW heparin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bFGF | 1 pg ml−1 | < 10 pg ml−1 | < 10 pg ml−1 | < 10 pg ml−1 | < 10 pg ml−1 | < 10 pg ml−1 |

| HGF | 40 pg ml−1 | 289.3 ± 87 pg ml−1 (95%CI: 245.73,332.27) | 47.0 fold increase | 4.1 fold increase | 30.9 fold increase | 5.4 fold increase |

| VEGF | 9 pg ml−1 | 137 ± 55 pg ml−1 95%CI: 109.65,164.35) | no change | no change | no change | no change |

Table 2.

Mean AUC(0,24 h) values for HGF following placebo, standard-or LMW-heparin treatment.

| AUC(0,24 h) (pg ml−1 24 h) | |

|---|---|

| Standard heparin group | |

| Placebo | 6999 ± 1976 (CI: 5480.11–8517.89) |

| Standard heparin s.c. | 8843 ± 3052 (CI: 6497.03–11890) |

| Standard heparin i.v. | 20574 ± 5916 (CI: 16027–251 21) |

| LMW heparin group | |

| Placebo | 77 25 ± 1334 (CI: 6699.6–8750.4) |

| LMW heparin s.c. | 125 29 ± 2544 (CI: 10574–14484) |

| LMW heparin i.v. | 14881 ± 3092 (CI: 12504–17258) |

The i.v. or s.c. injection of equivalent amounts of LMW-heparin also resulted in differing levels of HGF release (Figure 1b). I.v. application of LMW-heparin induced a significant rise from baseline values up to 8.28 ± 1.04 ng ml−1 (95%CI:7.48–9.08) after 10 min, corresponding to a 30.9 fold increase (P < 0.0001) above baseline. Levels remained significantly elevated for up to 3 h following i.v. injection (Figure 1b). Following s.c. delivery, HGF serum levels became significantly elevated after 10 min (P < 0.0001) and appeared to remain so for more than 6 h after injection. AUC(0,24 h) values of LMW-heparin following i.v. or s.c. administration showed no significant differences (Table 2). bFGF concentrations remained at baseline levels of less than 10 pg ml−1, irrespective of treatment. Mean serum concentrations of VEGF (137 ± 55 pg ml−1; 95%CI:107.65–162.35) were similarly unresponsive to either heparin, irrespective of the route of administration (Table 1).

Control experiments revealed that the addition of up to 1000 U ml−1 S-heparin or LMW-heparin to serum samples of untreated individuals showed no unspecific interference and no cross reactivity with the antibodies for bFGF or VEGF. Digestion of individual samples from untreated subjects with various amounts of heparinase I or heparinase II showed no influence on cytokine values measured (results not shown).

Discussion

A number of physiological effects have been ascribed to heparin, many of which are independent of its well characterized activity as an anticoagulant [20, 21]. Previous studies indicate that heparin is able to release more than 85% of the HGF bound to the cell surface of hepatocytes [22]. Furthermore, synthesis of HGF is stimulated by heparin in various cell lines and also from primary cells including human umbilical vein endothelial cells or skin fibroblasts [23]. Preliminary work from our group [17] and others [18, 37] indicates the same to be true in humans.

The present studies were designed to investigate the effects of S-heparin and LMW-heparin on levels of HGF, bFGF and VEGF, factors with well documented angiogenic properties in vivo. The results of these two, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover studies in healthy subjects demonstrate a strong and rapid increase in HGF serum levels after injection of S-heparin or LMW-heparin, two commonly used heparin preparations. Comparison of AUC(0,24 h) values for i.v. administration of both agents showed a more pronounced effect of S-heparin. Due to its different pharmacological properties, LMW-heparin may exert a more pronounced effect on maximum HGF levels upon s.c. administration, resulting in greater AUC(0,24 h) values compared with S-heparin. Both compounds and both routes of administration resulted in HGF concentrations capable of inducing profound chemotactic, angiogenic and mitogenic responses in vitro[5]. A clinical heparin therapy, comprising repetitive applications within 24 h, could lead to persistently elevated levels of circulating HGF during the treatment period.

In contrast to HGF, bFGF and VEGF levels were unaffected by treatment with heparins. Although heparin is reported to stimulate bFGF levels in both a rabbit model [24] and in patients during coronary artery bypass graft operations [25], we were not able to detect significant amounts of bFGF under our experimental conditions. This may be explained by the fact that factors differ substantially in affinities to heparin. However no studies adressing this issue specifically are currently available. bFGF values reported in this study are in accordance with previously published data on healthy, untreated individuals [19]. The fact that patients receive continuous drug infusion and higher doses of heparin could explain these discrepancies. VEGF serum levels in untreated individuals were also in agreement with published concentrations for healthy subjects [26].

Several growth factors including HGF, bFGF and VEGF show strong affinities for heparin and heparin-like molecules, which modulate the stability, localization and biological activity of these factors [27]. Low and high affinity binding sites for HGF have been detected on the surface of target cells, representing heparin or heparin sulphate proteoglycans on the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix. Furthermore, the interstitial collagens I, III, V, and VI, mediated by unique collagenous peptides, also serve as abundant, low-affinity binding sites for HGF in the extracellular matrix [28], and a heparin sulphate-bound form of HGF with identical properties can be purified from human serum [29].

The study design does not allow evaluation of the precise molecular mechanisms leading to the observed changes. Based on the findings, a likely mechanism may be that HGF is dissociated from the cellular surface and the extracellular matrix into the circulation by heparins.

Displacement of proteoglycan bound HGF from the cellular surface may result in enhanced clearance of HGF from the circulation and thus diminished bioactivity, although there is no direct evidence for this speculation. Based on the finding that some mutants of HGF with reduced binding to heparane sulphate proteoglycans may show a delayed clearance, higher tissue levels and enhanced activity in vivo[16]. This may facilitate therapeutic use of specifically engineered mutants of HGF [7].

Elevated levels of bioactive HGF in response to heparin may on the other hand lead to a shuttling of HGF to sites of tissue injury. Evidence for this notion comes from animal studies showing elevated HGF serum values as well as enhanced liver regeneration in partially hepatectomized rats after heparin administration [8]. In situations where the c-met receptor is locally upregulated, as demonstrated by Ono [11] during myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion, an elevation of HGF levels in response to heparin may help to initiate angiogenesis and neovascularization of damaged tissue. In fact, administration of standard heparin sulphate significantly increases collateral formation in various models of myocardial injury [30, 31]. In humans, heparin treatment improves exercise capacity, clinical symptoms and angiographically assessed increase in coronary collaterals in patients with coronary artery disease [32, 33]. Study periods were short however, and effects were only detectable under regular exercise protocols inducing repeated tissue ischaemia. In the present study, we did not evaluate whether therapeutically used higher doses of S-heparin or LMW-heparin lead to more pronounced effects on HGF serum values, as any increase in heparin dose would have entailed a risk of bleeding and other adverse effects for the study volunteers.

The HGF system is overexpressed in invasive cancer, including breast cancer, relative to non invasive cancer or normal conditions [34]. Transfection of breast cancer and glioma cell lines with HGF cDNA greatly enhances the ability of these cells to form solid tumours in animals [34]. Both the expression of HGF in malignant tumours and circulating levels of HGF in cancer patients are frequently increased [34, 35]. In primary breast cancer and multiple myeloma, high circulating HGF levels predict an unfavourable prognosis [35, 36]. These findings should be considered when using heparin in patients with malignancies.

In conclusion, the present data demonstrate that S- and LMW-heparin preparations induce a rapid, strong and selective release of HGF in humans. S-heparin and LMW-heparin exhibited comparable effects. Of greater consequence was the route of administration, where i.v. injection elicited a much more pronounced effect compared with s.c. administration for both agents. The application of HGF has well documented beneficial effects on organ regeneration and tissue repair. Further investigations are needed to asses the clinical relevance of the findings reported here, as heparin administration may either lead to enhanced clearance of bioactive HGF or to enhanced availability of HGF at sites of tissue injury which may have important implications in the treatment of patients with tissue ischaemia currently not amenable to conventional revascularization procedures, and may partially explain the effects of heparin treatment on the formation of new collaterals in patients with coronary heart disease.

References

- 1.Nakamura T, Nishizawa T, Hagiya M, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of human hepatocyte growth factor. Nature. 1989;342:440–443. doi: 10.1038/342440a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) as a tissue organizer for organogenesis and regeneration. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1997;239:639–644. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant SD, Kleinmann HK, Goldberg ID, et al. Scatter factor induces blood vessel formation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:1937–1941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bussolino F, Di Renzo MF, Ziche M, et al. Hepatocyte Growth factor is a potent angiogenic factor which stimulates endothelial cell mobility and growth. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:629–641. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.3.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Belle E, Witzenbichler B, Chen D, et al. Potentiated angiogenic effect of scatter factor/hepatocyte growth factor via induction of vascular endothelial growth factor. Circulation. 1998;97:381–390. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujiwara K, Nagoshi S, Ohno A, et al. Stimulation of liver growth by exogenous human hepatocyte growth factor in normal and partially heparectimized rats. Hepatology. 1993;18:1443–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradbury J. A two-pronged approach to the clinical use of HGF. Lancet. 1998;351:272. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)78259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Heparin functions as a hepatotrophic factor by inducing production of hepatocyte growth factor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1996;227:455–461. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakamura Y, Morishita R, Nakamura S, et al. A vascular modulator, hepatocyte growth factor, is associated with systolic pressure. Hypertension. 1996;3:409–413. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsumori A, Furukawa Y, Hashimoto T, et al. Increased circulating hepatocyte growth factor in the early stages of acute myocardial infarction. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1996;221:391–395. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ono K, Matsumori A, Shioi T, Furukawa U, Sasayama S. Enhanced expression of hepatocyte growth factor/c-Met by myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in a rat model. Circulation. 1997;95:2552–2558. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.11.2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauters C, Asahara T, Zheng LP, et al. Site specific therapeutic angiogenesis after systemic administration of VEGF. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21:314–324. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70272-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harada K, Grossman W, Friedman M, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor improves myocardial function in chronically ischemic porcine hearts. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:623–630. doi: 10.1172/JCI117378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Losordo DW, Vale PR, Symes JF, et al. Gene therapy for myocardial angiogenesis, initial clinical results with direct myocardial injection of phVEGF165 as sole therapy for myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 1998;98:2800–2804. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.25.2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.David D. Integral membrane heparane sulfate proteoglycans. FASEB J. 1993;7:1023. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.11.8370471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartmann G, Prospero T, Brinkmann V, et al. Engineered mutants of HGF/SF with reduced binding to heparane sulphate proteoglycans, decreased clearance and enhanced activity in vivo. Curr Biol. 1998;8:125–134. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salbach PB, Turovets O, Kreuzer J, Brachmann J, Walter-Sack I. Heparin is a potent inducer of hepatocyte growth factor activity in healthy humans. Naunyn Schmiedeberg's Arch Pharmakol. 1998;357(Suppl: 167) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumori A, Ono K, Okada M, Miyamoto T, Sato Y, Sasayama A. Immediate increase in circulationg hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor by heparin. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1998;30:2145–2149. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasdai D, Barak V, Leibovitz E, et al. Serum basic fibroblast growth factor levels in patients with ischaemic heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 1997;59:133–138. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)02921-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tyrell DJ, Kilfeather S, Page CP. Therapeutic uses if heparin beyond its traditional role as an anticoagulant. TIBS. 1995;16:198–204. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)89022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weitz JI. Low molecular weight heparins. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:688–698. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naka D, Ishii T, Shimomura T, Hishida T, Hara H. Heparin modulates the receptor-binding and mitotic activity of hepatocyte growth factor on hepatocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1993;209:317–324. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto K, Okazaki H, Nakamura T. Heparin as an inducer of HGF. J Biochem. 1993;114:820–828. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson RW, Whalen GF, Saunders KB, Hores T, D'ámore PA. Heparin mediated release of fibroblast growth factor-like activity into the circulation of rabbits. Growth Factors. 1990;3:221–220. doi: 10.3109/08977199009043906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medalion B, Merin G, Aingorn H, et al. Endogenous basic fibrolblast growth factor displaced by heparin from the lumenal surface of human blood vessels is preferentially sequestered by injured regions of the vessel wall. Circulation. 1997;95:1853–1862. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.7.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Los M, Aarsman CJ, Terpstra L, et al. Elevated ocular levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in paients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:1015–1022. doi: 10.1023/a:1008213320642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruoslathi E, Yamaguchi Y. Proteoglycans as modulators of growth factor activities. Cell. 1991;64:867–869. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90308-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuppan D, Schmid M, Somasundaram R, et al. Collagens in the liver extracellular matrix bind hepatocyte growth factor. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:139–152. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yano K, Tsuda E, Ueda M, Higashio K. Natural hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) from human serum and a bound form of recombinant HGF with heparan sulfate are indistinguishable in their physicochemical properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 1998;23:227–235. doi: 10.1016/s0141-8130(98)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchida Y, Yanagisawa-Miwa A, et al. Angiogenic therapy of acute myocardial infarction by intrpericardial injection of basic fibroblast growth factor and heparin sulfate: an experimental study. Am Heart J. 1995;130:1182–1188. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosengart TK, Budenbender KT, Duenas M, Mack CA, Zhang QX, Isom OW. Therapeutic angiogenesis: a comparative study of the angiogenic potential of acidic fibroblast growth factor and heparin. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:302–312. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(97)70193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasayama S, Fujita M. Recent insights into coronary collateral circulation. Circulation. 1992;85:1197–1204. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.3.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fujita M, Yamanishi K, Hirai T, Ohno A, Miwa K, Sasayama S. Comparative effect of heparin treatment with and without strenuous exercise on treadmill capacity in patients with stable effort angina. Am Heart J. 1991;122:453–457. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90999-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosen EM, Lamszus K, Laterra J, Polverini PJ, Rubin JS, Goldberg ID. HGF, /SF in angiogenesis. Ciba Found Symp. 1997;212:215–226. doi: 10.1002/9780470515457.ch14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toi M, Taniguchi T, Ueno T, et al. Significance of circulating hepatocyte growth factor level as a prognostic indicator in primary breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:659–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seidel C, Borset M, Turesson I, Abildgaard N, Sundan A, Waage A. Elevated serum concentrations of hepatocyte growth factor in patients with multiple myeloma. The nordic myeloma study group. Blood. 1998;91:806–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamazaki H, Oi H, Matsushita M, et al. Heparin induces rapid and remarkable elevation of hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor during trans arterial embolization of renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:1435–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]