Abstract

Aims

To characterize the effect of an oral contraceptive (OC) containing ethinylestradiol and gestodene on the activity of CYP3A4 in vivo as measured by the 1′-hydroxylation of midazolam.

Methods

In this randomised, double-blind, cross-over trial nine healthy female subjects received either a combined OC (30 µg ethinylestradiol and 75 µg gestodene) or placebo once daily for 10 days. On day 10, a single 7.5 mg dose of midazolam was given orally. Plasma concentrations of midazolam and 1′-hydroxymidazolam were determined up to 24h and the effects of midazolam were measured with three psychomotor tests up to 8 h.

Results

The combined OC increased the mean AUC of midazolam by 21% (95% CI 2% to 40%; P = 0.03) and decreased that of 1′-hydroxymidazolam by 25% (95% CI 10% to 41%; P = 0.01), compared with placebo. The metabolic ratio (AUC of 1′-hydroxymidazolam/AUC of midazolam) was 36% smaller (95% CI 19% to 53%; P = 0.01) in the OC phase than in the placebo phase. There were no significant differences in the Cmax, tmax, t½ or effects of midazolam between the phases.

Conclusions

A combined OC preparation caused a modest reduction in the activity of CYP3A4, as measured by the 1′-hydroxylation of midazolam, and slightly increased the AUC of oral midazolam. This study suggests that, at the doses used, ethinylestradiol and gestodene have a relatively small effect on CYP3A4 activity in vivo.

Keywords: CYP3A4, ethinylestradiol, gestodene, interaction, midazolam

Introduction

Ethinylestradiol and gestodene are exogenous female sex steroids commonly used in combined oral contraceptives (OC). Both ethinylestradiol and gestodene show affinity for cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 3A4, and gestodene, in particular, has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 in vitro[1–3]. Although OCs have been shown to inhibit the CYP-mediated metabolism of many therapeutic drugs and thereby increase their plasma concentrations [4–8], most of these interactions are of minor clinical importance. Nevertheless, some drugs may be more susceptible to interaction with OCs, as demonstrated by a recent study that found a 10- to 20-fold higher serum selegiline concentration in females using OCs containing ethinylestradiol and gestodene or levonorgestrel compared with females not receiving concomitant medications [9].

Midazolam, a short-acting benzodiazepine, has an extensive first-pass metabolism, resulting in an oral bioavailability of about 50% [10]. Midazolam is metab-olized in the liver by CYP3A4 to two active metabolites, 1′-hydroxymidazolam and 4-hydroxymidazolam [11–13]. The 1′-hydroxylation of midazolam is catalysed almost exclusively by CYP3A4 [11, 14], and can thus be used to assess CYP3A4 activity in humans [15–17]. In this study, we have characterized the effects of a combined OC containing ethinylestradiol and gestodene on CYP3A4 activity using oral midazolam as a probe drug in healthy volunteers.

Methods

Subjects

Nine female volunteers (age range, 20–25 years; weight range, 57–70 kg) participated in this study after having given their written informed consent. None of the subjects was a smoker or used any concomitant medications. The subjects were ascertained to be in good health by medical history, clinical examination and standard haematological and blood chemistry tests. Pregnancy was excluded by a pregnancy test. The study protocol was approved by the joint Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Turku, and Turku University Central Hospital.

Protocol

The study was performed as a randomised, double-blind cross-over trial, with a wash-out period of 8 weeks between the two phases. The subjects took either an OC preparation containing 30 µg ethinylestradiol and 75 µg gestodene (Femoden®, Schering, Germany) or matched placebo once daily (between 08.00 and 10.00 h) for 10 days. On day 10, after an overnight fast, the subjects received a single 7.5 mg dose of midazolam (Dormicum®, Hoffmann La-Roche, Switzerland) orally 1 h after the intake of the last OC or placebo dose. Venous blood samples (10 ml) were collected into lithium-heparin tubes just before and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12 and 24h after the ingestion of midazolam. Plasma was separated and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Compliance with OC intake was confirmed by determination of the plasma gestodene concentration in the samples taken 1, 2, 4, 7, 13 and 25 h after the last OC dose on day 10. Fasting was continued for 3 h after the administration of midazolam. Consumption of alcohol, grapefruit juice and caffeine-containing beverages was not allowed on the study days.

Analytical methods

The plasma concentrations of midazolam and 1′-hydroxy-midazolam were determined by a validated gas-chromatographic method [18]. The limit of quantification was 2.0 ng ml−1 for both midazolam and 1′-hydroxy-midazolam. The interassay coefficient of variation (CV) was < 10% at midazolam concentrations of 2.9 ng ml−1 (n = 9) and 30.0 ng ml−1 (n = 9) and at 1′-hydroxymidazolam concentrations of 3.3 ng ml−1 (n = 9) and 28.4 ng ml−1 (n = 9).

Plasma gestodene concentrations were determined by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) after solid phase extraction. Analyses were carried out on a system consisting of a PE Series 200 Autosampler, two PE 200 Micro Pumps and an API 365 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with a TurboIonSpray (TIS) ionization source (Perkin Elmer Sciex Instruments, Norwalk, CT, USA). Briefly, gestodene was extracted from 1 ml plasma using C18 BondElut cartridges (Varian Associates Inc., Harbor City, CA, USA). Ethisterone was used as an internal standard. The extract was evaporated to dryness under a stream of nitrogen at 40 °C. The residue was dissolved in 100 µl of the LC mobile phase and 20 µl was injected into the LC column. For chromatography, a Symmetry® C18 column (3.5 µm; 2.1 × 50 mm) (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) was used. The mobile phase consisted of 60% methanol in 2 mm ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4.7). The limit of quantification was 0.5 ng ml−1. The interassay CV was 5.4% and 0.7% at gestodene concentrations of 0.6 ng ml−1 and 4.0 ng ml−1, respectively.

Pharmacodynamics

The pharmacodynamic effects of midazolam were assessed by using three different validated psychomotor tests: a 2 min digit symbol substitution test (DSST), the number of button clicks made in 30 s and a 100 mm long visual analogue scale (VAS) for subjective drowsiness [19]. The subjects had been trained to do the tests prior to the study. The tests were performed before and 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 h after midazolam intake.

Data analysis

The peak concentrations (Cmax) and times to peak (tmax) of midazolam and 1′-hydroxymidazolam were taken from the original measured values. The other pharmacokinetic parameters were calculated by standard noncompartmental methods. The area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC) was calculated by using the linear trapezoidal rule and extrapolation to infinity by dividing the last quantifiable concentration by the elimination rate constant (kel), determined by linear regression analysis. The elimination half-life (t½) was calculated from t½ = ln2/kel. The metabolic ratio was calculated by dividing the AUC of 1′-hydroxymidazolam by the AUC of midazolam. The AUC(0,24h) of gestodene (i.e. the AUC between 1 and 25 h after the last OC dose) was calculated by the trapezoidal rule. For each psychomotor test, areas under the effect against time curve from 0 to 8 h [AUC(0,8 h)] were calculated by the trapezoidal rule.

Results are given as mean ± s.d.; tmax is given as median with ranges. 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for all variables except tmax. The pharmaco-kinetic variables and the AUC(0,8 h) values for the psychomotor tests between the OC and placebo phases were compared with a paired t-test (two-tailed). The Wilcoxon test was used for analysis of tmax. The Spearman rank correlation test was used to examine the possible relationship between gestodene AUC(0,24h) and the change in the midazolam AUC or in the metabolic ratio. The level of statistical significance was P < 0.05.

Results

Pharmacokinetics

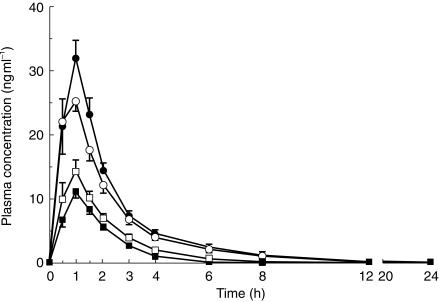

The plasma concentrations of midazolam were slightly higher and those of 1′-hydroxymidazolam were slightly lower in the OC phase compared with the placebo phase (Figure 1). Intake of the combined OC preparation for 10 days produced a 21% mean increase in the AUC of midazolam (95% CI 2% to 40%, P = 0.03; Table 1). An increase in midazolam AUC was evident in most subjects, the greatest individual increase being 76%. No significant differences were found in the Cmax, tmax or t½ of midazolam between the phases. The combined OC preparation decreased the mean AUC of 1′-hydroxymidazolam by 25% (95% CI 10% to 41%, P = 0.01; Table 1). The mean metabolic ratio (AUC of 1′-hydroxymidazolam/AUC of midazolam) was reduced by 36% (95% CI 19% to 53%; P = 0.01) in the OC phase compared with the placebo phase (Table 1). The decrease in the metabolic ratio was greatest in the subjects with the highest metabolic ratio in the placebo phase.

Figure 1.

Plasma midazolam (circles) and 1′-hydroxymidazolam (squares) concentrations in nine healthy subjects (mean ± s.e. mean) after a 7.5 mg oral dose of midazolam, following intake of a combined OC preparation (solid symbols) or placebo (open symbols) once daily for 10 days.

Table 1.

The pharmacokinetic variables of midazolam and 1′-hydroxymidazolam and the pharmacodynamic variables in nine healthy subjects after 7.5 mg oral midazolam, following intake of a combined OC preparation or placebo once daily for 10 days.

| Variable | OC phase | Placebo phase (control) | Mean percentage difference between OC and placebo (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | |||

| AUC (ng ml−1 h) | 72 ± 16* | 60 ± 13 | 21% (2% to 40%) |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 36 ± 8.6 | 31 ± 9.3 | 24% (−12% to 61%) |

| tmax (h) | 1 (0.5−1.5) | 1 (0.5−1) | – |

| t½ (h) | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 22% (−20% to 64%) |

| 1′-Hydroxymidazolam | |||

| AUC (ng ml−1 h) | 21 ± 2.5* | 30 ± 8.1 | −25% (−10% to −41%) |

| Cmax (ng ml−1) | 12 ± 2.1 | 15 ± 5.1 | −13% (−35% to 9%) |

| tmax (h) | 1 (0.5−1.5) | 1 (0.5−1) | – |

| t½ (h) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | −21% (−42% to 1%) |

| Metabolic ratio | 0.31 ± 0.08* | 0.54 ± 0.23 | −36% (−19% to −53%) |

| Pharmacodynamic variables† | |||

| Subjective drowsiness (VAS) (mm h) | 291 ± 38.1 | 284 ± 68.7 | 10% (−18% to 37%) |

| DSST (digits h) | 886 ± 89.7 | 870 ± 119 | 3% (−3% to 8%) |

| Button clicks (clicks h) | 1160 ± 79.5 | 1160 ± 71.3 | 0% (−2% to 2%) |

Data are mean ± s.d.; tmax values are given as median with range.

Significantly (P < 0.05) different from the placebo phase.

Shown as areas under the effect against time curve from 0 to 8 h [AUC(0,8 h)] calculated by the linear trapezoidal rule.

There was no significant correlation between the AUC(0,24h) of gestodene and the change in the AUC of midazolam (r = 0.067; P = 0.87) or in the metabolic ratio (r = 0.25; P = 0.52). The AUC(0,24h) of gestodene averaged 83.7 ± 26.3 ng ml−1 h. No gestodene was detected in the samples drawn after intake of the last placebo capsule.

Pharmacodynamics

There were no significant differences in the pharmacodynamic effects of midazolam between the OC and placebo phases (Table 1), as measured by the DSST, the button click test and subjective drowsiness.

Discussion

In this study, intake of an OC preparation containing ethinylestradiol and gestodene for 10 days resulted in a slight but statistically significant increase in midazolam AUC. On the other hand, the AUC of 1′-hydroxymidazolam was slightly but significantly lower in the OC phase than in the placebo phase. These findings suggest an inhibitory effect of the OC preparation on the formation of 1′-hydroxymidazolam. This is also evidenced by the metabolic ratio of midazolam (AUC of 1′-hydroxymidazolam/AUC of midazolam), which was 36% lower in the OC phase compared with placebo. The t½ of midazolam was not affected by the OC, suggesting that inhibition of 1′-hydroxymidazolam formation took place mainly in the first-pass phase and not in the elimination phase.

The extensive first-pass metabolism of midazolam and the evidence that CYP3A4 catalyses midazolam 1′-hydroxylation make this a suitable metabolic pathway to study the effects of drugs on CYP3A4 activity in vivo[16, 17]. For example, the AUC of oral midazolam was increased over 10-fold by ketoconazole and itraconazole [20], which are potent inhibitors of CYP3A4 [21]. Midazolam and 1′-hydroxymidazolam do not seem to be P-glycoprotein substrates [22], and thus the mechanism of the reduced formation of 1′-hydroxymidazolam caused by the combined OC is most probably inhibition of CYP3A4.

Gestodene is a very potent mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP3A4 in vitro[2]. For example, gestodene strongly inhibits the CYP3A4-mediated 2-hydroxylation of ethinyl-estradiol [2, 3]. Some years ago, gestodene was reported to increase plasma concentrations of ethinylestradiol [23], but later studies have refuted this finding [24, 25]. There seem to be no reports concerning the effects of gestodene on the pharmacokinetics of CYP3A4 substrates other than ethinylestradiol. Ethinylestradiol has also been reported to inhibit CYP3A4 activity in vitro[1], and a few studies have addressed the effects of ethinylestradiol, either alone or in combination with a progestogen, on the pharmacokinetics of CYP3A4 substrates.

Use of a combined OC preparation containing ethinylestradiol (30 µg) and either dienogest or levonorgestrel for 21 days produced no significant effects on the pharmacokinetics of a single dose of oral nifedipine [26] but reduced the CYP3A4-dependent formation of the main metabolite dehydronifedipine. In the study of Slayter et al.[6], the systemic clearance of methylprednisolone was 33% lower and the AUC 49% higher in women using OCs (a triphasic preparation of ethinylestradiol + levonorgestrel) than in women not using OC steroids. Furthermore, OC preparations containing ethinylestradiol and levonorgestrel or desogestrel have been reported to increase blood concentrations of cyclosporin, a clinically important CYP3A4 substrate [27, 28]. Stoehr et al.[4] assessed the effects of oestrogen-containing (< 35 µg ethinylestradiol) OCs on the pharmacokinetics of oral triazolam and alprazolam. In users of OCs, the AUC of alprazolam was 35% higher than in the control group. There were no statistically significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of triazolam, although the AUC of triazolam was increased by about 40% by OCs. A later study showed no significant differences in the pharmacokinetics of oral alprazolam between users of low-dose oestrogen-containing OCs and drug-free control women [29].

Our finding of a rather modest effect of the combined OC preparation on midazolam pharmacokinetics is thus in line with the available data on its effects on the pharmacokinetics of CYP3A4 substrates. It seems that although ethinylestradiol and especially gestodene can inhibit CYP3A4 in vitro[1–3], the low doses used clinically do not result in concentrations that effectively inhibit CYP3A4 in vivo. It should be noted, however, that the inhibitory effect of the OC on midazolam 1′-hydroxylation was strongest in the subjects with the highest metabolic ratio in the placebo phase. This suggests that clinically relevant interactions are possible in individuals with high CYP3A4 activity when an OC containing ethinylestradiol and gestodene is used concomitantly with a CYP3A4 substrate with a narrow therapeutic range, such as cyclosporin [27].

In conclusion, the OC preparation containing ethinyl-estradiol and gestodene caused a 36% reduction of CYP3A4 activity in vivo, as measured by midazolam 1′-hydroxylation. However, the resulting 21% increase in midazolam AUC did not enhance the clinical effects of midazolam. Thus, the interaction between the OC preparation containing ethinylestradiol and gestodene and oral midazolam is likely to be of minor clinical importance. Therefore clinically used doses of ethinyl-estradiol and gestodene will have a relatively small effect on the activity of CYP3A4 in vivo.

References

- 1.Guengerich FP. Metabolism of 17 alpha-ethynylestradiol in humans. Life Sci. 1990;47:1981–1988. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90431-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guengerich FP. Mechanism-based inactivation of human liver microsomal cytochrome P-450 IIIA4 by gestodene. Chem Res Toxicol. 1990;3:363–371. doi: 10.1021/tx00016a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Back DJ, Houlgrave R, Tjia JF, Ward S, Orme ML. Effect of the progestogens, gestodene, 3-keto desogestrel, levonorgestrel, norethisterone and norgestimate on the oxidation of ethinyloestradiol and other substrates by human liver microsomes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1991;38:219–225. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(91)90129-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoehr GP, Kroboth PD, Juhl RP, Wender DB, Phillips JP, Smith RB. Effect of oral contraceptives on triazolam, temazepam, alprazolam, and lorazepam kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;36:683–690. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1984.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pazzucconi F, Malavasi B, Galli G, Franceschini G, Calabresi L, Sirtori CR. Inhibition of antipyrine metabolism by low-dose contraceptives with gestodene and desogestrel. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1991;49:278–284. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1991.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slayter KL, Ludwig EA, Lew KH, Middleton E, Jr, Ferry JJ, Jusko WJ. Oral contraceptive effects on methylprednisolone pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1996;59:312–321. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(96)80009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Back DJ, Orme ML. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions with oral contraceptives. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990;18:472–484. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199018060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shenfield GM. Oral contraceptives. Are drug interactions of clinical significance? Drug Safety. 1993;9:21–37. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199309010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laine K, Anttila M, Helminen A, Karnani H, Huupponen R. Dose linearity study of selegiline pharmacokinetics after oral administration: evidence for strong drug interaction with female sex steroids. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47:249–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00891.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00891.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allonen H, Ziegler G, Klotz U. Midazolam kinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:653–661. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kronbach T, Mathys D, Umeno M, Gonzalez FJ, Meyer UA. Oxidation of midazolam and triazolam by human liver cytochrome P450IIIA4. Mol Pharmacol. 1989;36:89–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorski JC, Hall SD, Jones DR, VandenBranden M, Wrighton SA. Regioselective biotransformation of midazolam by members of the human cytochrome P4503A (CYP3A) subfamily. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;47:1643–1653. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mandema JW, Tuk B, van Stevenick AL, Breimer DD, Cohen AF, Danhof M. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of the central nervous system effects of midazolam and its main metabolite alpha-hydroxymidazolam in healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1992;51:715–728. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1992.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thummel KE, Shen DD, Podoll TD, et al. Use of midazolam as a human cytochrome P450 3A probe: I. In vitro–in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thummel KE, Shen DD, Podoll TD, et al. Use of midazolam as a human cytochrome P450 3A probe: II. Characterization of inter– and intraindividual hepatic CYP3A variability after liver transplantation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:557–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olkkola KT, Aranko K, Luurila H, et al. A potentially hazardous interaction between erythromycin and midazolam. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;53:298–305. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelkonen O, Mäenpää J, Taavitsainen P, Rautio A, Raunio H. Inhibition and induction of human cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes. Xenobiotica. 1998;28:1203–1253. doi: 10.1080/004982598238886. 10.1080/004982598238886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sunzel M. Determination of midazolam and the alpha-hydroxy metabolite by gas chromatography in small plasma volumes. J Chromatogr. 1989;491:455–460. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)82865-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hindmarch I. Psychomotor function and psychoactive drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;10:189–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1980.tb01745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olkkola KT, Backman JT, Neuvonen PJ. Midazolam should be avoided in patients receiving the systemic antimycotics ketoconazole or itraconazole. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;55:481–485. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Schmider J, et al. Midazolam hydroxylation by human liver microsomes in vitro: inhibition by fluoxetine, norfluoxetine, and by azole antifungal agents. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36:783–791. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1996.tb04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim RB, Wandel C, Leake B, et al. Interrelationship between substrates and inhibitors of human CYP3A and P-glycoprotein. Pharm Res. 1999;16:408–414. doi: 10.1023/a:1018877803319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung-Hoffmann C, Kuhl H. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral contraceptive steroids: factors influencing steroid metabolism. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;163:2183–2197. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)90560-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siekmann L, Siekmann A, Bidlingmaier F, Brill K, Albring M. Gestodene and desogestrel do not have a different influence on concentration profiles of ethinylestradiol in women taking oral contraceptives – results of isotope dilution mass spectrometry measurements. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;139:167–177. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1390167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammerstein J, Daume E, Simon A, et al. Influence of gestodene and desogestrel as components of low-dose oral contraceptives on the pharmacokinetics of ethinyl estradiol (EE2), on serum CBG and on urinary cortisol and 6 beta-hydroxycortisol. Contraception. 1993;47:263–281. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(93)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balogh A, Gessinger S, Svarovsky U, et al. Can oral contraceptive steroids influence the elimination of nifedipine and its primary pyridine metabolite in humans? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:729–734. doi: 10.1007/s002280050543. 10.1007/s002280050543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deray G, le Hoang P, Cacoub P, Assogba U, Grippon P, Baumelou A. Oral contraceptive interaction with cyclosporin. Lancet. 1987;1:158–159. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91988-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maurer G. Metabolism of cyclosporine. Transplant Proc. 1985;17:19–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scavone JM, Greenblatt DJ, Locniskar A, Shader RI. Alprazolam pharmacokinetics in women on low-dose oral contraceptives. J Clin Pharmacol. 1988;28:454–457. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1988.tb05759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]