Abstract

Aims

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effects of cilnidipine, a novel dihydropyridine calcium antagonist, on autonomic function, ambulatory blood pressure and heart rate in patients with essential hypertension.

Methods

Ten inpatients with mild to moderate essential hypertension (four men and six women; age: 44–64 years) underwent a drug-free period for 7 days and a treatment period with cilnidipine 10 mg orally for another 7 days, in a randomized crossover study. On the sixth day of each period, they underwent autonomic function tests including a mental arithmetic test, a cold pressor test and a Valsalva manoeuvre. After these tests, 24 h ambulatory blood pressure, heart rate, and the electrocardiogram R-R intervals were monitored every 30 min. A power spectral analysis of R-R intervals was performed to obtain the low-and high-frequency components.

Results

Cilnidipine significantly decreased the 24 h blood pressure by 6.5 ± 1.7 mm Hg systolic (mean ± s.e.mean; P > 0.01) and 5.0±1.1 mmHg diastolic (P > 0.01), whereas cilnidipine did not change heart rate or any indices of power spectral components. During the cold pressor test, the maximum change in systolic blood pressure and percentage changes in both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were significantly lower during the treatment period with cilnidipine than during the drug-free period. The baroreflex sensitivity measured from the overshoot phase of the Valsalva manoeuvre did not differ significantly between the two periods.

Conclusions

Cilnidipine is effective as a once-daily antihypertensive agent and causes little influence on heart rate and the autonomic nervous system in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. Moreover, it is suggested that cilnidipine has an additional clinical benefit in the inhibition of the pressor response induced by acute cold stress.

Keywords: ambulatory blood pressure, autonomic function, calcium antagonist, cilnidipine, cold pressor, heart rate variability, heart rate

Introduction

Cilnidipine is a novel and unique dihydropyridine calcium antagonist that possesses a slow-onset, long-lasting vasodilating effect [1]. Cilnidipine was reported to inhibit the release of [3H]-noradrenaline from sympathetic nerve endings in the rat mesenteric vasculature [2]. Recently, cilnidipine was found to have potent inhibitory action on the N-type as well as the L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones [3]. Regarding the clinical advantages of cilnidipine over other dihydropyridines, we have shown that cilnidipine has less influence on heart rate and the autonomic nervous system than nifedipine Retard and causes less tachycardia than nisoldipine in hypertensive patients [4, 5]. Moreover, in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs), cilnidipine was reported to cause an inhibition of the pressor response induced by acute cold stress in addition to its hypotensive effect [6]. This finding appears to be, at least in part, explained by its unique pharmacological properties. However, no randomized studies have been carried out to investigate whether this finding applies to hypertensive patients.

The present study was undertaken (1) to investigate the effects of cilnidipine on ambulatory blood pressure, heart rate and heart rate variability and (2) to clarify other clinical benefits of cilnidipine including an inhibition of the pressor response induced by acute cold stress in patients with essential hypertension.

Methods

Patients

Ten inpatients with mild to moderate essential hypertension participated in this study. The purposes and detailed procedures of the study protocol were explained, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cardiovascular Center. Patients had a systolic blood pressure greater than 160 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure greater than 95 mmHg, or both, on at least three occasions at the outpatient clinic. Secondary causes of hypertension were ruled out by comprehensive screening including medical history, physical findings, urinalysis, blood chemistry and endocrinological and radiological examinations when needed. All patients had normal renal function as judged by endogenous creatinine clearance.

According to the World Health Organization criteria for organ damage, all patients were classified as having stage I or II hypertension. Any medications being used were withheld for at least 2 weeks prior to the study.

Study protocol

Before entering the study, patients stayed in a ward for several days to minimize the effect of hospitalization on blood pressure and other variables during the protocol. Half of the patients then underwent a drug-free period for 7 days and a treatment period with cilnidipine for another 7 days. The other five patients underwent these periods in the reverse order, i.e. the order of the drug-free and the treatment periods was randomized to avoid time-related effects on blood pressure and other variables. Cilnidipine was administered at a dose of 10 mg orally every morning. All patients rose by 06.00 h and went to bed by 21·30 h throughout the study period. They spent the entire 24 h on the ward and consumed a regular diet containing 1700 kcal and 120 mmol NaCl per day throughout the study period. On the sixth day of each period, they underwent three autonomic function tests. After these tests, 24 h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring was performed.

Autonomic function tests

The procedure of the autonomic function tests has been described in detail elsewhere [7]. After resting in the sitting position in a quiet room for 30 min, the subjects underwent a mental arithmetic test, a cold pressor test and a Valsalva manoeuvre. These tests were carried out in the morning with the patient fasted and in the sitting position. Patients were left in a silent room with an ambient temperature of about 22°C. After a period of 15—20 min for attachment of the blood pressure measurement device, baseline blood pressure and heart rate were determined at rest and subsequently during the test period. Three consecutive measurements were averaged and used for later analyses. These tests were carried out in the same sequence in each period, and before going on to the next test, subjects rested for at least 15 min to allow blood pressure and heart rate to return to baseline. The tests were as follows:

Mental arithmetic test: follow the continuous performance of simple arithmetic exercise for 5 min. The patients were instructed to work as accurately as possible. Most patients used subtraction of 17 from 1,000, but because of difficulty with calculation a few used subtraction of 7 from 100.

Cold pressor test: soak one hand up to the wrist in 4°C water for 1 min.

Valsalva manoeuvre: exhale and hold a sphygmo- manometer at 40 mmHg for 15 s. During this manoeuvre, a nose clip was used to avoid leakage of breath from the nose. Baroreflex sensitivity (BRS) was calculated from changes in blood pressure and R-R interval during an overshoot phase (phase IV) [8]. During these tests, beat-to- beat blood pressure and R-R interval were monitored continuously using a finger photoplethysmographic device (Finapres; Ohmeda, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The device provides an accurate estimate of beat-to-beat blood pressure recording [9]. The difference between the value during the pretest and the peak value during the test period was taken as the reactivity of blood pressure in the mental arithmetic and the cold pressor tests.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and power spectral analysis of R-R intervals

24 h ambulatory blood pressure was monitored every 30 min using the cuff-oscillometric device, TM-2425 (A & D Co., Tokyo, Japan). The accuracy of this device has previously been reported [10]. The daytime and the nighttime blood pressures were defined as the average values in the awake period between 06.00 h and 21.30 h and in the sleeping period between 22.00 h and 05.30 h, respectively. The same recorder was used in each subject for the entire protocol to avoid potentially different blood pressure (BP) readings from different recorders.

The ambulatory BP recorder used in the present study, TM-2425, also monitored the R-R interval of the electrocardiogram. The procedures of the power spectral analysis of R-R intervals using this device have been previously reported in detail [11, 12]. The frequency range of 0.05–0.15 Hz was computed as the low-frequency (LF) component, which is an index of both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve activities. The frequency range of 0.15–0.40 Hz was computed as the high-frequency (HF) component, which reflects parasympathetic nerve activity. The LF/HF ratio was calculated as an index of sympatho-vagal balance [13].

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as means± s.e. mean. Comparisons between the drug-free period and the treatment period with cilnidipine were carried out using Student's t-test. For comparisons of power spectral measurements, the natural logarithmic values, i.e. ln (the LF component), ln (the HF component), or ln (the LF/HF ratio), were used to normalize the skewed data. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All 10 patients completed the study protocol. Their baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study patients.

| Women/Men | 6/4 |

| Age (years) | 56.6 ± 1.8 |

| Height (cm) | 159 ± 3 |

| Weight (kg) | 60.8 ± 2.6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.0 ± 0.6 |

| Office systolic BP (mmHg) | 168 ± 7 |

| Office diastolic BP (mmHg) | 103 ± 4 |

| Office pulse rate (beats min−1) | 70.2 ± 2.3 |

| Duration of hypertension (years) | 4.0 ± 1.1 |

Values are means± s.e.mean. BP; blood pressure.

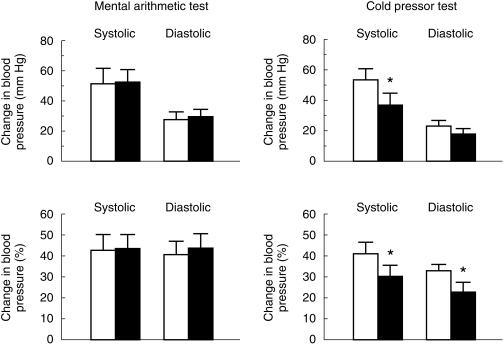

Figure 1 depicts maximum and percentage changes in blood pressure during the mental arithmetic and the cold pressor in the drug-free period and the treatment period with cilnidipine. During the mental arithmetic test, maximum and percentage changes did not differ significantly between the two periods. During the cold pressor test, the maximum change in systolic blood pressure was significantly lower in the treatment period with cilnidipine than in the drug-free periodby 15.7 ± 7.6 mmHg (95% CI: 1.0; 30.4, P < 0.05). Percentage changes in both systolic and diastolic blood pressures were also significantly lower during the treatment period with cilnidipine than during the drug-free period by 11.2 ± 5.2% systolic (95% CI 1.0, 21.4, P < 0.05) and by 10.2 ± 4.3% diastolic (95% CI 1.8, 18.6, P < 0.05), respectively. During these two tests, changes in heart rate did not differ significantly between the two periods. The BRS values assessed by a Valsalva manoeuvre did not differ significantly between the two periods (cilnidipine 8.5 ±2.6 ms/mmHg, drug-free 8.5 ± 2.9 ms/mmHg).

Figure 1.

Maximum and percentage changes in blood pressure during the mental arithmetic and the cold pressor tests in the drug-free period (open bar) and the treatment period with cilnidipine (closed bar). Values are expressed as means ± s.e.mean. * P < 0.05 vs the drug-free period.

Table 2 lists the 24 h, daytime, and night-time average values of ambulatory blood pressure and heart rate during the two periods. Cilnidipine significantly decreased the 24 h blood pressure by 6.5 ± 1.7 mmHg systolic (95% CI 3.2, 9.9, P < 0.01) and 5.0±1.1 mmHg diastolic (95% CI: 2.9; 7.0, P < 0.01) and the daytime blood pressure by 5.9±1.4 mmHg systolic (95% CI 3.0, 8.7, P < 0.01) and 5.2±1.2 mmHg diastolic (95% CI 2.9, 7.6, P < 0.01). Cilnidipine also decreased the night-time blood pressure to a similar extent, although a decrease in diastolic blood pressure was not statistically significant (P = 0.09). Table 3 lists the average values for the 24 h period, daytime and night-time blood pressures. Cilnidipine did not significantly change the heart rate, the LF component, the HF component, and the LF/HF ratio during a 24 h period in these patients.

Table 2.

Blood pressure and heart rate during the drug-free period and the treatment period with cilnidipine.

| Drug-free | Cilnidipine | Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | |||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 130.3±3.4 | 123.8±3.2** | 3.2, 9.9 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 83.6±2.8 | 78.7±2.7** | 2.9, 7.0 |

| Heart rate (beats minx1) | 62.7±2.1 | 64.2±2.4 | −3.4, 0.4 |

| Daytime | |||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 131.9±3.0 | 126.0±3.0** | 3.0, 8.7 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 85.7±2.7 | 80.5±2.2** | 2.9, 7.6 |

| Heart rate (beats minx1) | 66.7±2.3 | 68.1±2.4 | −3.7, 0.9 |

| Night-time | |||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 127.1±4.7 | 119.2±4.3* | 2.5, 13.2 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 79.4±3.2 | 75.0±3.9 | −0.1, 8.9 |

| Heart rate (beats minx1) | 54.8±2.0 | 56.4±2.6 | −4.1, 0.9 |

Values are meansts.e.mean. BP; blood pressure.

P < 0.05

P < 0.01 vs the drug- free period.

Table 3.

Power spectral data during the drug-free period and the treatment period with cilnidipine

| Drug-free | Cilnidipine | Difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | |||

| LF, ln (ms2) | 4.61 ± 0.09 | 4.67 ± 0.10 | −0.16, 0.04 |

| HF, ln (ms2) | 4.11 ± 0.21 | 4.18 ± 0.21 | −0.25, 0.13 |

| ln (LF/HF) | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 0.49 ± 0.15 | −0.19, 0.18 |

| Daytime | |||

| LF, ln (ms2) | 4.64 ± 0.09 | 4.70 ± 0.11 | −0.19, 0.06 |

| HF, ln (ms2) | 3.91 ± 0.18 | 3.97 ± 0.23 | −0.29, 0.16 |

| ln (LF/HF) | 0.73 ± 0.13 | 0.74 ± 0.18 | −0.26, 0.25 |

| Night-time | |||

| LF, ln (ms2) | 4.55 ± 0.15 | 4.60 ± 0.17 | −0.25, 0.13 |

| HF, ln (ms2) | 4.53 ± 0.30 | 4.59 ± 0.24 | −0.37, 0.25 |

| ln (LF/HF) | 0.02 ± 0.20 | 0.01 ± 0.15 | −0.21, 0.22 |

Values are means ± s.e.mean. LF: the low-frequency component; HF: the high-frequency component.

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated that cilnidipine inhibited the pressor response induced by acute cold stress in 10 inpatients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. This finding is in agreement with an earlier experimental observation that cilnidipine caused an inhibition of the pressor response induced by acute cold stress in addition to its hypotensive effect in SHRs, while other dihydropyridine calcium antagonists such as nifedi-pine, nicardipine and manidipine failed to inhibit the pressor response by acute cold stress [6]. The earlier finding suggests that the inhibitory effect of cilnidipine on cold pressor response may not be related to its calcium channel blocking action on the L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels [6]. The pressor effect in response to cold stress is known to be attenuated by the administration of α-adrenoceptor blocking agents [14]. Conversely, dihydropyridine calcium antagonists, including nilvadipine, nicardipine, nisoldipine and felodipine, have been reported not to affect the pressor response induced by acute cold stress in both hypertensive and normotensive subjects [15–18]. For example, Takabatake et al.[17] reported that the pressor responses to stress tests such as mental arithmetic, cold pressor and exercise tests were not affected by nicardipine 20 mg orally in 15 patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension. Hanko et al.[18] also reported that felodipine did not influence the pressor response to a cold pressor test in 16 normotensive subjects.

The underlying mechanism by which cilnidipine inhibited the pressor response induced by acute cold stress appears to be explainable by earlier experimental studies [3, 19]. Cilnidipine was reported not to inhibit the vasoconstriction induced by exogenous noradrenaline in the rabbit aorta [19], suggesting that cilnidipine has no blocking action against α-adrenergic receptors. Therefore, it is unlikely that the inhibitory effect of cilnidipine on the pressor response induced by acute cold stress is due to a postsynaptic α-adrenoceptor blocking action. Recently, cilnidipine was found to have potent inhibitory action on the N-type as well as the L-type voltage-dependent calcium channels in rat dorsal root ganglion neurones using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique [3]. Both types of channels were inhibited by similar concentration ranges: the median inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for cilnidipine block of L-type and N-type calcium channels were 100 nm and 200 nm, respectively. A number of studies have reported that N-type voltage-dependent calcium channels, which are distributed only in neuronal cells, especially sympathetic neuronal cells, were intimately involved in sympathetic neurotransmission and regulated the release of noradrenaline from sympathetic nerve endings [20–24]. For example, intravenous administration of ω-conotoxin, GVIA, a specific N-type voltage-dependent calcium channel blocker, inhibits nitroprusside-induced tachycardia in SHRs [25]. Moreover, acute cold stress is well-known to cause a remarkable increase in plasma noradrenaline levels in humans [26] as well as SHRs [6]. Taken together, it is thought that in the treatment period with cilnidipine, the attenuated pressor response induced by acute cold stress was due to the inhibitory effect on noradrenaline release from the sympathetic nerve endings through the N-type calcium channel blocking action.

We recently reported that blood pressure levels are significantly higher in winter than in summer in patients with essential hypertension, using ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring [27, 28]. It has also been shown that cardiovascular events such as acute myocardial infarction and stroke increase during cold seasons [29, 30]. Besides hypercoagulability, sympathetic activation and elevated blood pressure induced by a cold climate are thought to contribute to an increase in these events. Therefore, cilnidipine may have clinical advantages over other dihydropyridine calcium antagonists with respect to prevention against cardiovascular events during cold seasons.

In the present study, cilnidipine failed to inhibit the pressor response induced by the mental arithmetic test. It was reported that only a minor increase in noradrenaline and a significant increase in adrenaline were observed after mental stress, suggesting that mental stress mainly activates the sympatho-adrenal system rather than the vascular sympathetic nervous system [31]. As cilnidipine is thought to inhibit noradrenaline release from the sympathetic nerve endings [2], but not to affect the adrenal medulla [6], this suggests that cilnidipine significantly inhibited the pressor response induced by acute cold stress, while it failed to inhibit the pressor response induced by mental stress.

Recently many studies regarding the relationship between the short-acting calcium antagonists of dihydro-pyridines and the risk of myocardial infarction have been reported [32–34]. Short-acting calcium antagonists cause an increase in sympathetic nerve activation and reflex tachycardia. Increased sympathetic tone may represent a coronary risk factor in hypertensive patients [35]. Moreover, the clinical utility of the short-acting calcium antagonists is limited by the incidence of unfavourable side-effects such as headache, flushing, dizziness or palpitations [36]. It is thought that such side-effects are caused by acute vasodilatation and reflex activation of the sympathetic nervous system. In the present study, heart rate and the power spectral measurements did not differ significantly between the drug-free period and the treatment period with cilnidipine, indicating that cilnidipine has the potential not to affect heart rate and the autonomic nervous system. Therefore, cilnidipine appears to be safe and beneficial for the treatment of hypertension.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, this study design was not a double-blind approach to the comparison of placebo and active cilnidipine 10 mg daily. Moreover, the present finding would have been strengthened if pure L-type dihydropyridine calcium antagonists such as nifedipine had been included as a control. Therefore, further studies are needed to clarify the relationship between the unique pharmacological properties of cilnidipine and its clinical benefits over other dihydropyridines in the treatment of essential hypertension.

In conclusion, cilnidipine is effective as a once-daily antihypertensive agent and causes little influence on heart rate and autonomic nervous system in patients with mildly to-moderately essential hypertension. Moreover, it is suggested that cilnidipine has an additional benefit such as the inhibition of the pressor response induced by acute cold stress.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Masahiro Hosono, Ph.D., for critical reading of the manuscript. This study was supported by funds for Comprehensive Research on Aging and Health 94A2101 from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Tokyo, Japan and by a grant from Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan.

References

- 1.Yoshimoto R, Dohmoto H, Yamada K, Goto A. Prolonged inhibition of vascular contraction and calcium influx by the novel 1,4-dihydropyridine calcium antagonist cinaldipine (FRC-8653) Jpn J Pharmacol. 1991;56:225–229. doi: 10.1254/jjp.56.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosono M, Fujii S, Hiruma T, et al. Inhibitory effect of cilnidipine on vascular sympathetic neurotransmission and subsequent vasoconstriction in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1995;69:127–134. doi: 10.1254/jjp.69.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujii S, Kameyama K, Hosono M, Hayashi Y, Kitamura K. Effect of cilnidipine, a novel dihydropyridine Ca+ +-channel antagonist, on N-type Ca+ + channel in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. l997;280:1184–1191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minami J, Ishimitsu T, Kawano Y, Numabe A, Matsuoka H. Comparison of 24-hour blood pressure, heart rate, and autonomic nerve activity in hypertensive patients treated with cilnidipine or nifedipine retard. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;32:331–336. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199808000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minami J, Ishimitsu T, Higashi T, Numabe A, Matsuoka H. Comparison between cilnidipine and nisoldipine with respect to effects on blood pressure and heart rate in hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 1998;21:215–219. doi: 10.1291/hypres.21.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosono M, Hiruma T, Watanabe K, et al. Inhibitory effect of cilnidipine on pressor response to acute cold stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1995;69:119–125. doi: 10.1254/jjp.69.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makino Y, Kawano Y, Okuda N, et al. Autonomic function in hypertensive patients with neurovascular compression of the ventrolateral medulla oblongata. J Hypertens. 1999;17:1257–1263. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huikuri HV, Pikkujamsa SM, Airaksinen KE, et al. Sex-related differences in autonomic modulation of heart rate in middle-aged subjects. Circulation. 1996;94:122–125. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parati G, Casadei R, Groppelli A, Di Rienzo M, Mancia G. Comparison of finger and intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring at rest and during laboratory testing. Hypertension. 1989;13:647–655. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tochikubo O, Ikeda A, Miyajima E, Ishii M. Effects of insufficient sleep on blood pressure monitored by a new multibiomedical recorder. Hypertension. 1996;27:1318–1324. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Minami J, Kawano Y, Ishimitsu T, Takishita S. Blunted parasympathetic modulation in salt-sensitive patients with essential hypertension: evaluation by power-spectral analysis of heart-rate variability. J Hypertens. 1997;15:727–735. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minami J, Ishimitsu T, Matsuoka H. Effects of smoking cessation on blood pressure and heart rate variability in habitual smokers. Hypertension. 1999;33:586–590. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagani M, Lombardi F, Guzzetti S, et al. Power spectral analysis of heart rate and arterial pressure variabilities as a marker of sympatho—vagal interaction in man and conscious dog. Circ Res. 1986;59:178–179. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank SM, Raja SN. Reflex cutaneous vasoconstriction during cold pressor test is mediated through alpha-adrenoceptors. Clin Auton Res. 1994;4:257–261. doi: 10.1007/BF01827431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takabatake T, Yamamoto Y, Nakamura S, et al. Effect of the calcium antagonist nilvadipine on haemodynamics at rest and during cold stimulation in essential hypertension. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;33:215–219. doi: 10.1007/BF00637551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasanisi F, Soro S, Ferrara LA. Responses to sympathetic stimulation and tilting during antihypertensive treatment with nisoldipine. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1991;17:405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takabatake T, Yamamoto Y, Nakamura S, et al. Effect of nicardipine on haemodynamic response to stress in hypertension. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;42:265–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00266346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanko E, Rostrup M. Calcium antagonist treatment and cardiovascular responses to a cold pressor test at high altitude. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;51:265–267. doi: 10.1007/s002280050195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosono M, Iida H, Ikeda K, et al. In vitro and ex vivo Ca-antagonistic effect of 2-methoxyethyl (E)-3-phenyl-2-propen-1-yl(+/−)-1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-4-(3-nitrophenyl) pyridine-3,5-dicarboxylate (FRC-8653), a new dihydropyridine derivative. J Pharmacobiodyn. 1992;15:547–553. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.15.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirning LD, Fox AP, McCleskey EW, et al. Dominant role of N-type Ca2 + channels in evoked release of norepinephrine from sympathetic neurons. Science. 1988;239:57–61. doi: 10.1126/science.2447647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clasbrummel B, Osswald H, Illes P. Inhibition of noradrenaline release by omega-conotoxin GVIA in the rat tail artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;96:101–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pruneau D, Angus JA. Omega-conotoxin GVIA is a potent inhibitor of sympathetic neurogenic responses in rat small mesenteric arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;100:180–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rittenhouse AR, Zigmond RE. Omega-conotoxin inhibits the acute activation of tyrosine hydroxylase and the stimulation of norepinephrine release by potassium depolarization of sympathetic nerve endings. J Neurochem. 1991;56:615–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb08194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabi F, Chiavarelli M, Argiolas L, Chiavarelli R, del Basso P. Evidence for sympathetic neurotransmission through presynaptic N-type calcium channels in human saphenous vein. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:338–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pruneau D, Belichard P. Haemodynamic and humoral effects of omega-conotoxin GVIA in normotensive and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;211:329–335. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90389-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LeBlanc J, Cote J, Jobin M, Labrie A. Plasma catecholamines and cardiovascular responses to cold and mental activity. J Appl Physiol. 1979;47:1207–1211. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1979.47.6.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minami J, Kawano Y, Ishimitsu T, Yoshimi H, Takishita S. Seasonal variations in office, home and 24 h ambulatory blood pressure in patients with essential hypertension. J Hypertension. 1996;14:1421–1425. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minami J, Ishimitsu T, Kawano Y, Matsuoka H. Seasonal variations in office and home blood pressures in hypertensive patients treated with antihypertensive drugs. Blood Press Monit. 1998;3:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas AS, Dunnigan MG, Allan TM, Rawles JM. Seasonal variation in coronary heart disease in Scotland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49:575–582. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.6.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheth T, Nair C, Muller J, Yusuf S. Increased winter mortality from acute myocardial infarction and stroke: the effect of age. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1916–1919. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward MM, Mefford IN, Parker SD, et al. Epinephrine and norepinephrine responses in continuously collected human plasma to a series of stressors. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:471–486. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Meyerc JV. Nifedipine. Dose-related increase in mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:1326–1331. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, Koepsell TD, et al. The risk of myocardial infarction associated with antihypertensive drug therapies. JAMA. 1995;274:620–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Minami J, Ishimitsu T, Kawano Y, Matsuoka H. Effects of amlodipine and nifedipine retard on autonomic nerve activity in hypertensive patients. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1998;25:572–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Julius S. Sympathetic hyperactivity and coronary risk in hypertension. Hypertension. 1993;21:886–893. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.21.6.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bremner AD, Fell PJ, Hosie J, James IG, Saul PA, Taylor SH. Early side-effects of antihypertensive therapy: comparison of amlodipine and nifedipine retard. J Hum Hypertens. 1993;7:79–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]