Abstract

Aims

To determine whether there is a pharmacokinetic interaction between the antiepileptic drugs remacemide and phenobarbitone.

Methods

In a group of 12 healthy adult male volunteers, the single dose and steady-state kinetics of remacemide were each determined twice, once in the absence and once in the presence of phenobarbitone. The effect of 7 days remacemide intake on initial steady-state plasma phenobarbitone concentrations was also investigated.

Results

Apparent remacemide clearance (CL/F) and elimination half-life values were unchanged after 7 days intake of the drug in the absence of phenobarbitone (1.25 ± 0.32 vs 1.18 ± 0.22 l kg−1 h−1 and 3.29 ± 0.68 vs 3.62 ± 0.85 h, respectively). Concomitant administration of remacemide with phenobarbitone resulted in an increase in the estimated CL/F of remacemide (1.25 ± 0.32 vs 2.09 ±0.53 l kg−1 h−1), and a decreased remacemide half-life (3.29 ± 0.68 vs 2.69 ± 0.33 h). The elimination of the desglycinyl metabolite of remacemide also appeared to be increased after the phenobarbitone intake (half-life 14.72 ± 2.82 vs 9.61 ± 5.51 h, AUC 1532 ± 258 vs 533 ± 281 ng ml−1 h). Mean plasma phenobarbitone concentrations rose after 7 days of continuing remacemide intake (12.67 ± 1.31 vs 13.86 ± 1.81 μg ml−1).

Conclusions

Phenobarbitone induced the metabolism of remacemide and that of its desglycinyl metabolite. Remacemide did not induce its own metabolism, but had a modest inhibitory effect on the clearance of phenobarbitone.

Keywords: drug interactions, epilepsy, pharmacokinetics, phenobarbitone, remacemide

Introduction

Remacemide [±−2-amino-N-(1-methyl-1,2-diphenylethyl) acetamide monohydrochloride] is a new antiepileptic drug which has low affinity noncompetetive N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) channel blocker with sodium-channel-blocking activity. Its desglycinyl metabolite is also active.

The two enantiomeric forms of remacemide have been isolated for preclinical testing in pharmacological models of epilepsy. The difference between either of the enantiomers and the parent drug in all of the preclinical tests conducted is considered to be of no biological significance [1].

When new antiepileptic drugs are used first, they are usually registered as add-on therapy to pre-existing antiepileptic drugs which have failed to control seizure disorders. To interpret the therapeutic situation in these circumstances it is desirable to know whether the new agent interacts pharmacokinetically with the concomitant therapy. Remacemide is metabolized by oxidation catalysed by cytochrome P450 isoenzymes, and by glucuronidation [2]. The latter two metabolic pathways are potentially heteroinducible, so that pharmacokinetic interactions between remacemide and inducing anticonvulsants such as phenytoin, carbamazepine and phenobarbitone would appear possible. Data from in vitro studies using human liver microsomes suggest that remacemide inhibits CYP3A4 and CYP2C19, which are important in the oxidations of carbamazepine and phenytoin, respectively [Data on file, AstraZeneca]. Subsequent clinical studies have indicated a moderate but predictable inhibition of carbamazepine metabolism by remacemide [3]. A small but clinically insignificant interaction was found between remacemide and phenytoin [4]. Moderate increases in phenytoin concentration were seen with remacemide. The magnitude of the rise observed is unlikely to present a pharmacokinetic barrier to their clinical use in combination, although possible pharmacodynamic interactions are yet to be determined.

It is much simpler to design clinical drug interaction studies which investigate the effect of one drug on the disposition of another, than to design studies which yield information regarding the effects of each drug on the other. Nevertheless in the present study an attempt was made to answer three questions; does remacemide induce its own metabolism; does phenobarbitone alter the pharmacokinetics of remacemide; does remacemide alter the pharmacokinetics of phenobarbitone?

Methods

The design of the study was approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee of the University of Queensland. The study was carried out in conformity with GCP standards.

Subjects studied

Fourteen healthy young adult male volunteers commenced the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers. Two subjects did not complete the protocol for personal reasons. Thirteen out of 14 subjects completed the first multiple dose remacemide hydrochloride phase of the study. The 14 subjects who entered the study had a mean age of 21.5 ± s.d. 1.8 years (range 19.4–25.9 years) and a mean weight of 79.3 ± s.d. 9.9 kg (67–104 kg).

Study design

All subjects took a single oral dose of remacemide hydrochloride, 300 mg, on the morning of day 1 and venous blood was collected at 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 30 and 36 h for a study of remacemide pharmacokinetics. Beginning on the evening of day 2, all subjects then took remacemide, 200 mg, orally, twice daily, until the morning of day 8, when venous blood samples were collected at the same times as on day 1; an additional sample was taken 48 h after the final dose. From day 10 to day 21, all subjects took oral phenobarbitone 30 mg day−1; from day 22 to day 35, phenobarbitone 60 mg day−1; and, from day 36 to day 57, phenobarbitone 90 mg day−1, the doses being taken at approximately 8 pm. On day 50, all subjects took an oral dose of remacemide hydrochloride, 300 mg, and the single dose remacemide pharmacokinetic study was repeated with the sampling times used on day 1. From the evening of day 51 until the morning of day 57, all subjects took oral remacemide 200 mg twice daily in addition to phenobarbitone. On the morning of day 57, another set of venous blood samples was collected with the timings as on day 8 for determination of remacemide pharmacokinetics. A blood sample was collected on the morning of day 59, 36 h after the final phenobarbitone dose, for measurement of the plasma phenobarbitone concentration. Single preremacemide dose blood collections were taken on the mornings of days 4, 7, 8, 53, 56 and 57 for estimation of remacemide concentrations, and on the mornings of days 48, 49, 50, 53, 56 and 57 for the estimation of 12 h postdose plasma phenobarbitone concentrations. A summary of the dosing schedule is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Treatment plan.

Measurements of plasma drug concentrations

Blood was collected into heparinized tubes, immediately chilled in ice, and plasma separated and frozen within one hour of blood collection. The frozen plasma samples were kept at −20 °C or below till analysed.

Remacemide and desglycinyl metabolite assay

Remacemide and the desglycinyl metabolite concentrations were determined in the plasma samples using a validated solid phase extraction (SPE), high performance liquid chromatography (h.p.l.c.) internal standard method. Validation of the method had demonstrated appropriate accuracy and precision for the determination of both analytes in the presence of several antiepileptic comedications, including phenobarbitone.

Plasma (1 ml) containing water (200 µl) and internal standard (50 µl) was vortex mixed in a glass tube and placed on a Gilson ASPEC robot. The automated solid phase extraction commenced with the addition of potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate (50 µm, 1.25 ml, adjusted to pH 2) to the plasma sample. The SPE cartridge (Propyl sulphonic acid, 100 mg) was preconditioned with acetonitrile (1 ml), acetonitrile/sodium hydrogen carbonate (0.15 m) 20/80 (3 ml) and potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate (1 ml, pH 2 adjusted). A 2.2 ml aliquot was taken from the diluted plasma sample and transferred to the SPE cartridge which was then washed with water (1 ml) and acetonitrile (1 ml). The cartridge was eluted with acetonitrile/sodium hydrogen carbonate (0.15 m), 20/80 (0.75 ml) and an aliquot of the extract (75 μl) injected onto an h.p.l.c. system. The analytes and internal standard were separated from any residual plasma constituents on a reverse phase ODS2-IK5 column eluted at 1.0 ml min−1 with an isocratic mixture of acetonitrile/potassium dihydrogen orthophosphate (0.15 m, pH unadjusted) 30/70. Detection of the analytes and internal standard was by u.v. absorbance at 210 nm. The concentration of the analytes in each sample was determined from regression analysis of the peak area ratios of analyte to internal standard. The calibration range of the method was 10–500 ng ml−1 for both remacemide and desglycinyl remacemide, with a limit of quantification for both analytes of 10 ng ml−1. Quality control samples included in each analysis batch contained remacemide and desglycinyl remacemide at concentrations of 20, 200 and 400 ng ml−1 each. For remacemide quality control samples, accuracies of 97.5, 98.5 and 95% were observed at 20, 200 and 400 ng ml−1, respectively, with corresponding precision values of 9.2, 5.3 and 7.2%. For desglycinyl remacemide quality control samples, accuracies of 95.5, 95.5 and 94.3% were at 20, 200 and 400 ng ml−1, respectively, with corresponding precision values of 16.4, 9.2 and 9.8%.

Phenobarbitone assay

Plasma phenobarbitone concentrations were measured by a fully validated h.p.l.c. procedure, which was shown to have satisfactory specificity, linearity, accuracy and precision over the phenobarbitone concentration range 0.5–50.0 µg ml−1 plasma. In the prestudy analytical validation studies, the analytical method for phenobarbitone in plasma was shown from repeated analyses of quality control samples to be precise to within ±9.9%, ± 7.8% and ±4.7% of the mean measured values of 1.06, 5.20 and 20.5 µg ml−1, respectively. The accuracy of the assay at the following concentrations: 1.0, 5.0 and 20.0 µg ml−1 was 94%, 95% and 96%, respectively.

Data analysis

Remacemide and the desglycinyl metabolite The plasma concentrations of remacemide and the desglycinyl metabolite, both with and without phenobarbitone, were measured and peak plasma concentrations (Cmax), time to maximum concentration (tmax) and the terminal half-life (t½) were determined after both single and multiple (steady-state) remacemide doses. The area under the plasma concentration vs time curve up to the last point (t) at which the concentration could be quantified (Ct) after a single dose, days 1 and 50 (AUCt) was estimated using the linear trapezoidal rule. The total area under the plasma concentration vs time curve (AUC) was estimated after single dose administration. For the repeated dose profile over a 12 h dosing interval (τ), days 8 and 57, AUCτ was also estimated using the linear trapezoidal rule. With the exception of tmax, the data were log transformed and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated for the ratio of phenobarbitone/no phenobarbitone; these data were antilogged for presentation [5]. Apparent clearances (CL/F) were determined as dose/AUCτ and dose/AUCτ after single and multiple dose administration, respectively.

Phenobarbitone

To obtain an appreciation of the extent of any change in plasma phenobarbitone concentrations after multiple dosing with remacemide hydrochloride, plasma phenobarbitone concentrations determined following 2, 5 and 6 days of multiple dosing (i.e. on the mornings of days 53, 56 and 57) were compared with the mean concentration determined on days 48, 49 and 50 (i.e. predose control concentrations prior to the start of remacemide hydrochloride intake). The percentage change was calculated as:

|

Terminal rate constants were calculated by linear regression analysis using the log concentration values at the times 12, 16, 20, 24 and 36 h following the last phenobarbitone dose.

Two-way anovas were applied to each group of timepoints and 95% CI calculated accordingly.

Results

Remacemide: Single vs multiple dose

There appeared to be little change in mean half-life and mean CL/F value between days 1 and 8. The observed degrees of accumulation (Rac) of remacemide and of the desglycinyl metabolite were determined from the values of AUC following single and AUCτ following repeated dosing on days 1 and 8. The mean±s.d. values were 1.16 ± 0.23 and 2.25 ± 0.57, respectively. In addition, the theoretical extent of accumulation (Rth) calculated from the elimination rate constant and assuming linear superposition was in good agreement with the observed values of Rac (mean±s.d. Rth = 1.09 ± 0.05 and 2.17 ± 0.35 for remacemide and its desglycinyl metabolite, respectively). These findings suggest that autoinduction of remacemide metabolic clearance did not appear to occur over this time period. Mean desglycinyl metabolite half-life also showed no change over this period.

Remacemide: Single dose with and without phenobarbitone

The time courses of the mean plasma concentrations of remacemide and the desglycinyl metabolite after the initial remacemide dose given on day 1, and after the second single remacemide dose given after exposure to phenobarbitone on day 50, are shown in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. The mean plasma desglycinyl metabolite concentrations are clearly lower after the second administration of the drug. Although the concentration-time profiles for remacemide appear similar, AUC was almost halved in the presence of phenobarbitone (Table 1). Confidence interval calculations for the differences between days 1 and 50, for the mean values of the drug and metabolite half-lives and AUCs are shown in Table 2, but only for the different numbers of subjects who provided data for each pairing of days. Table 1 also shows the corresponding data for the CL/F values for remacemide and the AUC values for the desglycinyl metabolite (because the extent of conversion of remacemide to its metabolite was not determined, clearances could not be calculated for the metabolite). Unfortunately, assay limitations compromised the available data for the metabolite, particularly in the studies carried out in the presence of phenobarbitone.

Figure 2.

Plot of the time courses of mean (+ s.d.) plasma remacemide concentrations after a single 300 mg oral dose of remacemide hydrochloride before (day 1, ▴) and after (day 50, □) exposure of the subjects to chronic phenobarbitone intake.

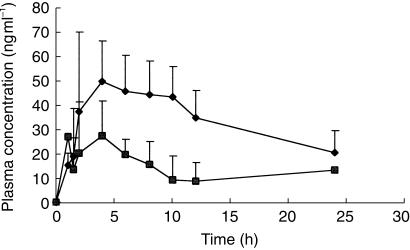

Figure 3.

Plot of the time courses of mean (+ s.d.) plasma desglycinyl metabolite concentrations after a single 300 mg oral dose of remacemide hydrochloride before (day 1, ♦) and after (day 50, ▪) exposure of the subjects to chronic phenobarbitone intake.

Table 1.

Mean (± s.d.) half-life values for remacemide and its desglycinyl metabolite, CL/F values for remacemide and AUC values for the desglycinyl metabolite at different stages of the study. The numbers in parenthesis are the numbers of subjects from whom each mean value was determined.

| Day | Remacemide t½ (h) | Desglycinyl metabolite t½ (h) | Remacemide CL/F (l kg−1 h−1) | Remacemide AUC (ng ml−1 h) | Desglycinyl metabolite AUC (ng ml−1 h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 3.29 ± 0.68 (13) | 14.72 ± 2.82 (8) | 1.25 ± 0.32 (13) | 3203 ± 593 (13) | 1532 ± 258(6) |

| 82 | 3.62 ± 0.80 (10) | 13.49 ± 2.98 (11) | 1.18 ± 0.22 (12) | 2236 ± 310 (12) | 692 ± 157 (12) |

| 503 | 2.69 ± 0.33 (11) | 9.61 ± 5.51 (4) | 2.09 ± 0.53 (11) | 1941 ± 401 (11) | 553 ± 281 (3) |

| 574 | 2.70 ± 0.43 (9) | 7.81 and 13.81 (2) | 1.99 ± 0.43 (10) | 1366 ± 263 (10) | 256 ± 91 (9) |

Single dose remacemide (300 mg).

Steady state remacemide (200 mg b.d.).

Single dose remacemide (300 mg) after approximately 6 weeks phenobarbitone dosing.

Steady state remacemide (200 mg b.d.) after approximately 7 weeks phenobarbitone dosing.

Table 2.

Confidence interval comparisons of the differences in the means for the various parameters at various stages of the study in subjects for whom measurements were available.

| Number of subjects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters compared | Day 1 or 8 | Day 50 or 57 | Geometric mean | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Remacemide AUC (ng ml−1h) | ||||

| Day 1 vs day 50 | 13 | 11 | 0.61 | 0.54, 0.68 |

| Day 8 vs day 57 | 12 | 10 | 0.61 | 0.54, 0.69 |

| Remacemide half-life (h) | ||||

| Day 1 vs day 50 | 13 | 11 | 0.83 | 0.66, 1.04 |

| Day 8 vs day 57 | 10 | 9 | 0.90 | 0.69, 1.17 |

| Desglycinyl metabolite AUC (ng ml−1h) | ||||

| Day 1 vs day 50 | 6 | 3 | 0.36 | 0.23, 0.54 |

| Day 8 vs day 57 | 12 | 9 | 0.36 | 0.28, 0.47 |

| Desglycinyl metabolite half-life (h) | ||||

| Day 1 vs day 50 | 8 | 4 | 0.48 | 0.38, 0.64 |

| Day 8 vs day 57 | 11 | 2 | 0.71 | 0.50, 1.02 |

The observed remacemide mean±s.d. half-life was lower on day 50 than on day 1; 2.69 ± 0.33–3.29 ± 0.68 (mean ratio 0.83; 95% CI 0.66, 1.04), and the drug's clearance increased from 1.25 ± 0.32–2.09 ± 0.53 l h−1 kg−1 (Table 1), suggestive of the presence of phenobarbitone-related hetero-induction of the metabolism of remacemide. The mean half-life of the metabolite (Table 1) was significantly shorter on day 50 than on day 1 (mean ratio 0.48; 95% CI 0.38, 0.64), see Table 2. Furthermore the mean AUC for this metabolite fell, suggesting that its biotransformation was also induced by chronic phenobarbitone intake.

Remacemide: Multiple dose with and without phenobarbitone

Table 1 shows the calculated mean elimination half-lives of remacemide and its desglycinyl metabolite after the initial and subsequent single doses of the drug, and after 7 days of intake of the drug in the absence (day 8) and presence (day 57) of exposure to phenobarbitone. Confidence interval calculations for the differences between days 8 and 57, for the mean values of the drug and metabolite half-lives and AUCs are shown in Table 2, but only for the different numbers of subjects who provided data for each pairing of days. Comparison of the pharmacokinetic parameters which applied after 7 days of remacemide intake (on day 8), and after a similar period of intake following 7 weeks exposure to phenobarbitone on day 57, demonstrated a higher CL/F value following phenobarbitone intake. While the observed mean half-life was shorter after phenobarbitone intake no definitive statements can be made given the variability in the data (mean ratio 0.90; 95% CI 0.69, 1.17). The plasma AUC of the desglycinyl metabolite was reduced although no firm conclusions could be drawn about half-life as data were only available in two subjects on day 57.

Phenobarbitone

Phenobarbitone dosing at 90 mg commenced on day 36, and plasma phenobarbitone concentrations measured 12 h postdose on days 48, 49 and 50, were reasonably constant (mean±s.d. values, respectively, 12.87 ± 1.78, 12.97 ± 1.56 and 12.67 ± 1.31 mg l−1), as shown in Figure 4, so that effective steady-state conditions had been achieved. By day 57, with an unaltered phenobarbitone dosage but with remacemide having been taken for 7 days, the mean ± s.d. plasma phenobarbitone concentration had risen to 13.86 ± 1.81 mg l−1 (geometric mean ratio 1.08, 95% CI 1.04, 1.12). At this time the mean±s.d. phenobarbitone half-life was 133 ± 62 h, so that the full increase in plasma phenobarbitone concentration associated with the presence of remacemide may not have had time to develop. The percentage increase in plasma phenobarbitone concentration, calculated as described above, was 9.1%.

Figure 4.

Phenobarbitone (□) mean plasma (s.d.) concentrations at steady-state (days 48–50) and day 50 (remacemide 300 mg single dose, ▴), days 53–57 (multiple dose remacemide 200 mg b.d., dashed line) and days 58 and 59 (washout). Solid line: duration of phenobarbitone treatment 90 mg o.d.

Discussion

The study described in this report was designed to answer three separate questions concerning remacemide in a single investigation. The progressive build-up of phenobarbitone dosage prolonged the study, but probably avoided subjects experiencing sedation which might have caused reluctance to remain in the investigation. Only two of the original 14 subjects dropped out. Sufficient subjects completed the study to permit reasonably clear conclusions to be made.

The study demonstrated that exposure to remacemide (defined by the AUC) was reduced to about 60% in the presence of phenobarbitone after both single and multiple remacemide doses. Exposure to the desglycinyl metabolite of the drug, following a single dose of remacemide, was also significantly decreased in the presence of phenobarbitone, with its t½ decreasing to less than 50% of the baseline value.

The corresponding pharmacokinetic data for the desglycinyl metabolite exhibited a statistically significant difference following single dose remacemide administered alone and in the presence of phenobarbitone. Although there also was a statistically significant difference in the pharmacokinetics of the desglycinyl metabolite following multiple dosage of remacemide alone, and in the presence of phenobarbitone, this finding was based on incomplete data due to subject withdrawals and analytical limitations. Therefore, these findings are less robust than those for the single dose pharmacokinetics.

The increased clearance of remacemide and reduced exposure to the desglycinyl metabolite in the presence of phenobarbitone is likely to result from induction, by phenobarbitone, of several CYP450 isoforms. Furthermore, as phenobarbitone increases oxidative metabolism over other routes, it is possible that a decrease in the proportion of parent drug being desglycinated may lead to a decrease in exposure to the desglycinyl metabolite.

The present study also demonstrated that remacemide had apparently increased the former steady-state plasma level of phenobarbitone by about 9% at the time when the study was terminated. The clinical importance of this is equivocal and the change is difficult to explain mechanistically. Phenobarbitone is cleared through three major routes: direct renal excretion, oxidative metabolism to its p-hydroxy derivative and conjugative metabolism to an N-glucoside derivative. Although remacemide, in vitro, is a modest inhibitor of certain cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (CYP3A4 and CYP2C19) [Data on file, AstraZeneca] there is little evidence regarding which P450 isoenzyme catalyses the oxidative metabolism of phenobarbitone. However, it is known that clinically significant increases in plasma phenobarbitone concentrations due to valproate coadministration involve inhibitions of both the N-glucosidation of phenobarbitone itself and the O-glucuronidation of the p-hydroxy derivative of phenobarbitone [6].

The multiple dosage profiles for both remacemide and its desglycinyl metabolite, in the absence and the presence of phenobarbitone, were generally predictable from those following a single dose. Accordingly, it can be concluded that there was no evidence that auto-induction of the metabolism of either remacemide of its desglycinyl metabolite occurred.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sr ME McIntyre for management of the clinical studies, Mr M.E. Franklin and Mr N. Entwistle for assistance with the analytical work, Dr T. Jones for pharmacokinetic input and AstraZenenca R & D Charnwood for funding the study.

References

- 1.Garske GE, Palmer GC, Napier JJ, et al. Preclinical profile of the anticonvulsant remacemide and its enantiomers in the rat. Epilepsy Res. 1991;9:249–255. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(91)90050-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark B, Hutchison JB, Jamieson V, et al. Potential antiepileptic drugs: remacemide hydrochloride. In: Levy RH, Mattson RH, Meldrum BS, editors. Antiepileptic Drugs. 4. New York: Raven Press; 1995. pp. 1035–1044. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leach JP, Blacklaw J, Jamieson V, et al. Mutual interaction between remacemide hydrochloride and carbamazepine: two drugs with active metabolites. Epilepsia. 1996;37:1100–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leach JP, Girvan J, Jamieson V, et al. Mutual interaction between remacemide hydrochloride and phenytoin. Epilepsy Res. 1997;26:381–388. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(96)01005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Confidence intervals rather than P values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. Br Med J. 1986;292:746–750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6522.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernus I, Dickinson RG, Hooper WD, et al. Inhibition of phenobarbitone N-glucosidation by valproate. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;38:411–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04375.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]