Abstract

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) is primarily produced in the liver during inflammation and regulates biological activities of IGF-I. Here we demonstrate that interleukin-1β (IL-1β) stimulates IGFBP-1 mRNA production in a dose-dependent manner in hepatocytes from Fisher 344 rats. Employment of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor SP600125 resulted in 3-fold reduction of IGFBP-1 mRNA and protein levels, indicating that IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1 production is mediated through JNK activation. We further show that hepatocytes from aged rats (20-22 mo), as compared to young (3-4 mo), exhibit up to 2-fold higher levels of IGFBP-1 in response to IL-1β. IL-1β-induced phosphorylation of JNK was also significantly higher in aged hepatocytes, and SP600125 treatment eliminated age-related differences in IGFBP-1 mRNA production. Moreover, glutathione depletion in hepatocytes from young rats potently activated JNK, as well as increased IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1 mRNA levels, suggesting that age-related oxidative stress underlies the upregulated JNK activation and IGFBP-1 expression.

Keywords: IGFBP-1, inflammation, glutathione, JNK, liver, oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding proteins (IGFBPs) are serum proteins that bind IGF-I and regulate its turnover, transport and tissue availability [1]. Only free non-bound IGF-I is biologically active, therefore the abundance of IGFBPs modulates many physiological effects of IGF, including cellular growth, survival, proliferation, differentiation, cell motility and glucose uptake [2].

To date, six IGFBPs have been identified, and among them IGFBP-1 contributes to approximately 15% of total IGF-I binding. Nevertheless, it is the major determinant of the free IGF-I concentration [1], and the only IGFBP that exhibits tightly regulated expression [3]. While other IGFBPs are expressed in various peripheral tissues, IGFBP-1 is produced primarily by the liver, and under basal conditions insulin is the primary regulator of its transcription [3]. However, IGFBP-1 production is potently upregulated in humans and rodents in response to sepsis [4], endotoxin injection [5, 6] and other inflammatory stimuli. It has been suggested that increased circulating levels of IGFBP-1 maintain the inflammatory catabolic state by diminishing the levels of bioavailable IGF-I and thereby counteracting its anabolic effects [7]. This observation is supported by data from IGFBP-1-overexpressing transgenic mice, which manifest pre- and postnatal growth retardation, reduction in organ size and pre-diabetic glucose metabolism pattern [8], indicating that IGFBP-1 is capable of potently offsetting physiological functions of IGF-I.

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is one of the primary stimulators of IGFBP-1 biosynthesis under inflammatory conditions. IL-1β injection in vivo results in increased circulating IGFBP-1 levels [9], and IL-1 receptor antagonist administration prior to experimental induction of sepsis attenuates IGFBP-1 production [4]. IL-1β also stimulates IGFBP-1 mRNA production in the HepG2 hepatocarcinoma cell line through mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway activation [10, 11].

Notably, one of the most intriguing functions of IGF-I is related to its role in aging. Aging is characterized by declining levels of bioactive IGF-I [12], resulting in halted cell growth, impaired tissue renewal, frailty and reduced glucose tolerance [13, 14]. However, it is still obscure whether aging has a noteworthy effect on the production of IGFBP-1, in part due to the lack of physiologically relevant systems to study the effects of aging. It has, however, been demonstrated that primary hepatocytes cultured on Matrigel preserve their physiological functions [15], as well as age-related differences such as age-associated decrease in cytochrome P450 expression [15, 16], thereby rendering this cell culture system an excellent model for aging studies. In this study we use primary Fisher344 rat hepatocytes cultured on thick Matrigel matrix layer in the presence of insulin as the only growth factor to explore the effects of aging on the regulation of IGFBP-1 expression by IL-1β.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary hepatocyte isolation, culturing, and harvesting

Hepatocytes were isolated from ether-anesthetized young (3-4 months old) and aged (20-22 months old) male Fisher 344 rats (National Institute of Aging, Bethesda, MD) by collagenase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) perfusion [17] and cultured on Matrigel (BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA) as described [16]. Treatments with recombinant rat IL-1β (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were performed on the 5th day in culture. Where applicable, cells were pretreated with SP600125 or L-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine (BSO) (Sigma). After treatments, medium was aspirated and Matrigel reliquidified by incubating culture dishes with PBS containing 5mM EDTA for 30 min on ice. Cells were scraped and Matrigel was removed by centrifugation at 500g for 4 min, followed by one wash.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

After harvesting, cellular RNA was isolated following Trizol® (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA synthesis was primed using random hexamers (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and performed with 1.5 μg RNA and 4 U/sample Superscript II™ reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) following manufacturer’s recommendations.

Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analysis was performed following Taq DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) manufacturer’s recommendations. The following primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) were used: IGFBP-1, forward, 5′-ctacccatggagtgggaaga-3′; reverse, 5′-tgccctttcaaagcagaact-3′; β-actin, forward, 5′-tatggagaagatttggcacc-3′; reverse, 5′-gtccagacgcaggatggcat-3′. PCR products were visualized by ethidium bromide staining after 1.8% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Quantitative real time PCR analysis

Taqman™ rat IGFBP-1 gene expression (Rn00565713_m1) and rodent glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) control assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used according to manufacturer’s instructions. Reactions were performed in triplicates in 96-well plates on an ABI Perkin Elmer Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System, and analyzed with SDS 1.9.1 software (Applied Biosystems). Levels of IGFBP-1 mRNA were normalized to GAPDH mRNA.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

IGFBP-1 protein levels were assessed in medium. Equal volumes of treatment medium (1 ml) were applied to culture dishes containing equal cell numbers (1 mln), and 20 μl of medium were subsequently used for Western blotting. For total and phospho-JNK1&2, cells were lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM Na2VO4, 1 mM NaF, 1:200 (v/v) protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)), and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 16,000g for 10 min at 4°C. Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes and probed with specified antibodies (primary antibodies for phospho-JNK1/2, IL-1 receptor (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), total JNK1/2 (Sigma), IGFBP-1, cyclophilin A (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY); secondary alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibodies (Sigma)). Protein-antibody interactions were visualized using an ECF kit (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ).

JNK activity assay

JNK activity was measured by the immune complex protein kinase assay as described [18]. Briefly, anti-JNK antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was bound to protein A-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) by incubating for 1h at 4°C, and JNK was immunoprecipitated from 3×105 cell lysates overnight at 4°C. The immunoprecipitated JNK was incubated with GST-c-Jun (Biomol, Plymouth Meeting, PA) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP for 30min at 30°C. The reaction was terminated by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Phospho-GST-c-Jun was visualized by the phosphor imager analysis after resolving samples by SDS-PAGE.

Measurements of glutathione (GSH)

After harvesting, hepatocytes were suspended in 250 μl of PBS containing 5mM EDTA. 50 μl aliquot was taken for protein measurements for normalization, and 100 μl were used for GSH measurements by Bioxytech® GSH/GSSG-412™ assay kit (OXIS International, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Assuming equal variance across groups, differences were assessed using Student’s t test or two-way ANOVA where applicable.

RESULTS

IL-1β induces IGFBP-1 mRNA production in primary hepatocytes

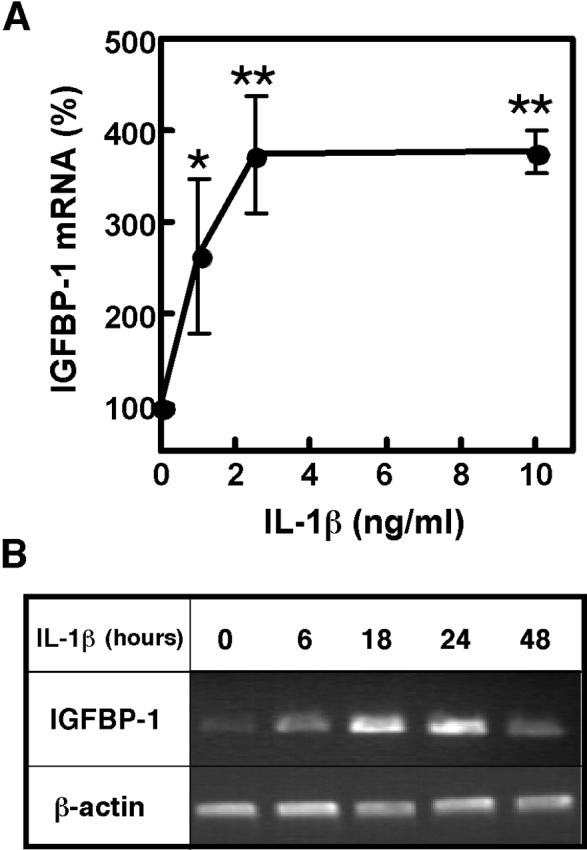

First, we tested whether IL-1β is sufficient to induce IGFBP-1 expression in primary rat hepatocytes. Cultured hepatocytes were treated with a range of IL-1β concentrations (Fig. 1A) for various times (Fig. 1B), and the levels of IGFBP-1 mRNA were assessed. Treatment with IL-1β induced IGFBP-1 mRNA elevation in a dose-dependent manner, reaching up to 3-4-fold induction at 10 ng/ml of IL-1β. The maximum induction of IGFBP-1 mRNA was observed at 24h after stimulation with IL-1β. These results are comparable with reports for HepG2 cells, where IGFBP-1 mRNA levels increased 4-fold after stimulation with 5 ng/ml of IL-1β, and the maximum induction was reached between 10 and 25h after IL-1β addition [10].

Fig. 1. IL-1β induces IGFBP-1 mRNA production in primary hepatocytes.

A. Dose response to IL-1β. Hepatocytes from 3-4 mo rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 24h. IGFBP-1 mRNA was quantified by real time PCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Results are expressed as % of normalized IGFBP-1 mRNA levels in non-treated cells. Values are mean ± SD, n=4, *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (compared to non-treated control). B. Time course of IL-1β stimulation. Hepatocytes from 3-4 mo rats were treated with IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for the indicated times, and IGFBP-1 mRNA levels were assessed by RT-PCR. β-actin mRNA levels were assessed for normalization.

IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1production is JNK-dependent

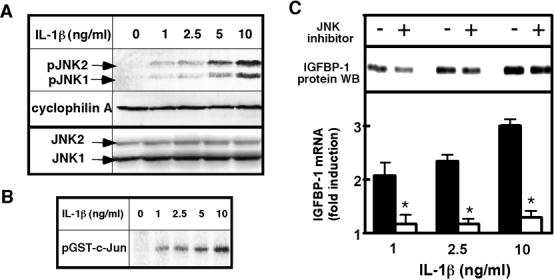

IL-1β is a potent inducer of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) phosphorylation in hepatocytes [17]; therefore, we sought to elucidate whether JNK is involved in IL-1β-mediated IGFBP-1 induction. We treated hepatocytes with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 30 min (Fig. 2A), which corresponds to the time point of maximum JNK phosphorylation [17]. As anticipated, the treatment resulted in dose-dependent phosphorylation (activation) of JNK. No differences in total JNK levels were observed after IL-1β treatment (Fig. 2A), as reported previously [19]. To confirm that phosphorylation results in increased activity, JNK activity was measured in vitro using GST-c-Jun as a substrate (Fig. 2B). JNK phosphorylation strongly correlated with increased c-Jun phosphorylation, confirming that phospho-JNK levels are a reliable indicator of overall JNK activity. To determine whether JNK activity is required for induction of IGFBP-1 mRNA production, hepatocytes were pretreated with JNK inhibitor SP600125 or its vehicle, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) prior to IL-1β treatment (Fig. 2C). Trypan Blue staining confirmed that cell viability was not affected by the inhibitor at concentrations as high as 100 μM. SP600125 treatment reduced basal IGFBP-1 mRNA levels on average by 50%. Moreover, in the presence of SP600125, IL-1β treatment resulted in only 40% increase in IGFBP-1 mRNA levels, compared to 300% increase observed in vehicle-treated cells. In addition, SP600125 correspondingly attenuated the IL-1β-induced increase in IGFBP-1 protein levels in the medium (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that JNK plays a crucial role in the induction of IGFBP-1 by IL-1β.

Fig. 2. IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1 production is JNK-dependent.

A. IL-1β-induced JNK phophorylation. Hepatocytes from 3-4 mo rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 30 min. Phospho-JNK1/2 levels (indicated by arrows as pJNK1 and pJNK2) were determined by Western blotting. Cyclophilin A is shown as a loading control. JNK1 and 2 (indicated by arrows as JNK1 and JNK2) are shown as a control for total JNK levels. B. IL-1β-induced JNK activity. Hepatocytes from 3-4 mo rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 30 min. JNK activity was measured using [γ-32P] ATP and GST-c-Jun as substrates. Phospho-GST-c-Jun was visualized by phosphor imager analysis after separation by SDS-PAGE. C. Effects of JNK inhibition on IGFBP-1 levels. Hepatocytes from 3-4 mo rats were pretreated with 20 μM JNK inhibitor SP600125 or vehicle (DMSO) prior to treatment with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 24h. IGFBP-1 mRNA was quantified by real time PCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Results are expressed as fold induction compared to normalized IGFBP-1 mRNA levels in non-treated cells in each group. Values are mean ± SD, n=3, *p<0.0001 (between respective IL-1β concentrations). IGFBP-1 protein levels were assessed in the medium by Western blotting, and the loading was normalized to cell number.

Aging upregulates IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1 production

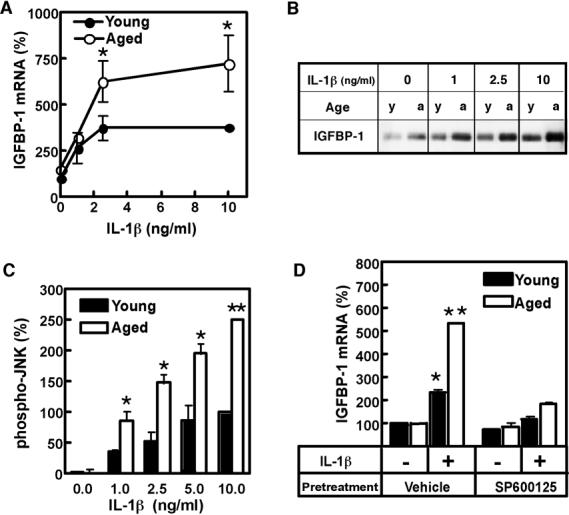

To test whether aging affects basal IGFBP-1 production, IGFBP-1 mRNA levels in hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) and aged (20-22 mo) rats were compared. Basal IGFBP-1 mRNA levels were found slightly higher in hepatocytes from aged rats, albeit the difference was not statistically significant. However, aging had a potent effect on the IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1 mRNA production (Fig. 3A). Notably, the levels of IGFBP-1 mRNA were substantially higher in aged hepatocytes at all concentrations of IL-1β, reaching 7-fold increase at 10 ng/ml of IL-1β, as compared to 3-4-fold increase in young cells at the same concentration of the cytokine. Western blotting analysis of the medium confirmed that aged hepatocytes secreted more IGFBP-1 protein under basal conditions and after IL-1β stimulation (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Aging upregulates IL-1β-induced production of IGFBP-1.

A. Age-related differences in IGFBP-1 mRNA levels. Hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) and aged (20-22 mo) rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 24h. IGFBP-1 mRNA was quantified by real time PCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Results are expressed as % of normalized IGFBP-1 mRNA levels in non-treated cells in each group. Values are mean ± SD, n=4, *p<0.001 (between respective IL-1β concentrations). B. Age-related differences in IGFBP-1 protein levels. Hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) (y) and aged (20-22 mo) (a) rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 24h. IGFBP-1 protein levels were assessed in the medium by Western blotting. The loading was normalized to cell number. C. Age-related differences in JNK phosphorylation. Hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) and aged (20-22 mo) rats were treated with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 30 min. Phospho-JNK1/2 levels were determined by Western blotting. The combined intensity of phospho-JNK1/2 was used for quantification. Levels of total JNK1/2, assessed by Western blotting, were used for normalization. Data are presented as % of normalized phospho-JNK1/2 levels at 10 ng/ml IL-1β in young hepatocytes. Values are mean ± SD, n=3, *p<0.01, **p<0.001 (between respective IL-1β concentrations). D. Effect of JNK inhibition on age-related differences in IGFBP-1 mRNA levels. Hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) and aged (20-22 mo) rats were pretreated with 20 μM JNK inhibitor SP600125 or vehicle (DMSO) prior to treatment with 0 ng/ml (-) or 2.5 ng/ml (+) of IL-1β for 24h. IGFBP-1 mRNA was quantified by real time PCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Results are expressed as % of normalized IGFBP-1 mRNA levels at 0 ng/ml IL-1β in vehicle-treated samples in young hepatocytes. Values are mean ± SD, n=3, *p<0.01, **p<0.0001 (compared to young control).

We further investigated whether phospho-JNK levels differ in IL-1β-treated young and aged hepatocytes (Fig. 3C). JNK phosphorylation in response to IL-1β was found substantially (2-3-fold) higher in hepatocytes isolated from aged rats, as compared to hepatocytes from young animals. Total JNK levels, as well as the levels of the IL-1 receptor type I were not affected by aging and were similar in young and aged hepatocytes, as reported previously [19].

To determine whether age-related increases in JNK phosphorylation are responsible for upregulation of IGFBP-1 levels, hepatocytes from young and aged rats were treated with IL-1β in the presence of SP600125 (JNK inhibitor) (Fig. 3D). The inhibitor did not affect cell viability of either aged or young hepatocytes. Notably, SP600125 treatment abolished age-related differences in IGFBP-1 mRNA production, suggesting that increased JNK activation is responsible for age-related upregulation of IGFBP-1 mRNA levels.

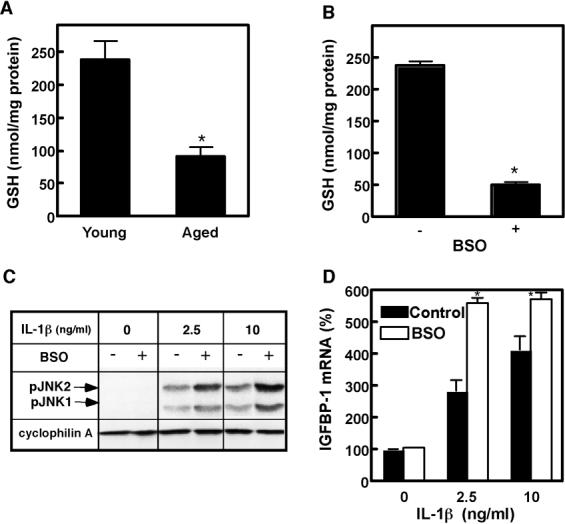

Age-related oxidative stress may cause upregulation of IL-1β-induced JNK activation and IGFBP-1 production

To begin understanding the mechanisms of the observed age-related differences, we tested whether oxidative stress contributes to age-related increase in IL-1β-induced phospho-JNK and IGFBP-1 levels. Hepatocytes from aged animals are known to exhibit the state of sustained oxidative stress, which manifests by increased steady-state production of reactive oxygen species and declined antioxidant capacity [20]. The leading cause of antioxidant decline in the aging liver is depletion of cellular glutathione (GSH) levels [21, 22]. We measured GSH levels in isolated hepatocytes from young and aged rats and also observed 50-70% depletion of GSH with age (Fig, 4A), which is in agreement with data reported for intact liver [21, 22]. Therefore, to mimic the process of aging, GSH levels in hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) rats were depleted by BSO, an inhibitor of GSH biosynthesis. 400 μM BSO concentration reduced GSH levels in young hepatocytes by 60-70%, comparable to the level found in aged hepatocytes (Fig. 4B). Notably, BSO treatment alone did not induce JNK phosphorylation in hepatocytes. However, it resulted in potent upregulation of JNK phosphorylation in response to IL-1β (Fig. 4C). Consequently, the IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1 mRNA production was substantially augmented (Fig. 4D). These results indicate that depletion of cellular GSH is sufficient to induce upregulation of both JNK phosphorylation and IGFBP-1 mRNA production in response to IL-1β, thereby implying that age-related oxidative stress may be responsible for the upregulation of IGFBP-1 levels with age.

Fig. 4. Oxidative stress causes upregulation of JNK phosphorylation and IGFBP-1 mRNA production.

A. GSH depletion with age. GSH levels were measured in hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) and aged (20-22 mo) rats. Values are mean ± SD, n=3, *p<0.01. B. GSH depletion by BSO treatment. Hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) rats were treated with 400 μM BSO for 24h. GSH levels were measured after the treatment. Values are mean ± SD, n=3, *p<0.001. C. Oxidative stress-potentiated JNK phosphorylation. Hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) rats were pretreated with 400 μM BSO prior to treatment with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 30 min. Phospho-JNK1/2 levels (indicated by arrows as pJNK1 and pJNK2) were determined by Western blotting. Cyclophilin A is shown as a loading control. D. Oxidative stress-potentiated IGFBP-1 mRNA production. Hepatocytes from young (3-4 mo) rats were pretreated with 400 μM BSO prior to treatment with the indicated concentrations of IL-1β for 24h. IGFBP-1 mRNA was quantified by real time PCR and normalized to GAPDH mRNA. Results are expressed as % of normalized IGFBP-1 mRNA levels of non-treated cells in each group. Values are mean ± SD, n=3, *p<0.001 (between respective IL-1β concentrations).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that aging augments IL-1β-stimulated IGFBP-1 production in primary rat hepatocytes, possibly through oxidative stress-mediated upregulation of JNK activity. Due to the ability of IGFBP-1 to counteract the effects of IGF-I, these observations may have important physiological implications. Increase in IGFBP-1 levels may contribute to the onset of catabolic state in aged individuals exemplified by the lack of proper tissue regeneration, sarcopenia, dementia, cardiovascular diseases and impaired glucose tolerance [13, 14]. These effects could be especially exacerbated by the concomitant decline in the serum IGF-I levels [12, 13, 23]. To date, there is no strong clinical data confirming that elevation of circulating IGFBP-1 levels is a universal aging trait. However, IGFBP-1 levels have been reported as being significantly higher in aged human subjects who are less healthy than their peers [24] or who have higher risk of cardiovascular diseases [25]. Notably, IGFBP-1 serum levels in humans inversely correlate with free IGF-I levels, suggesting that the lack of bioactive IGF-I may be linked to the described age-related health problems.

IL-1β is known as one of the primary inducers of IGFBP-1 production in vivo [4, 9] and in cell cultures, specifically, in HepG2 cells [10, 11]. The data presented here demonstrates that IL-1β alone is sufficient to induce IGFBP-1 production in primary rat hepatocytes. Studies in HepG2 cells showed that IGFBP-1 induction by IL-1β is mediated through the MAPK pathway [11]. Our study provides evidence that JNK activation is a critical step for IGFBP-1 mRNA induction in primary hepatocytes, since JNK inhibition almost completely abolished the IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1 mRNA elevation in hepatocytes. Nevertheless, other factors (possibly other MAPK kinases [11]) may still partially account for the IGFBP-1 mRNA production in hepatocytes, since residual elevation of IGFBP-1 mRNA was observed in the presence of the JNK inhibitor.

Importantly, age-related upregulation of the IL-1β-induced IGFBP-1 mRNA production also involves JNK activation, since (i) JNK phosphorylation in response to IL-1β was upregulated in hepatocytes from aged rats in parallel to the upregulation of IGFBP-1 mRNA induction, and (ii) JNK inhibition was sufficient to abolish age-related differences in IGFBP-1 levels. JNK is one of the major redox-sensitive molecules [26], and increased burden of reactive oxygen species and decreased antioxidant capacity have been postulated as hallmarks of aging cells [20, 27]. Here we provide evidence that depletion of GSH leads to upregulated JNK phosphorylation and IGFBP-1 mRNA production in IL-1β-stimulated hepatocytes. These findings suggest that age-related oxidative stress may affect key signaling enzymes such as JNK and result in dysregulated response to proinflammatory stimuli with age. However, further extensive studies are necessary in order to delineate the complex relationship between oxidative stress, IGFBP-1 and the health status in the elderly.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging grant RO1 AG019223 (to MNN-K) and a pre-doctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (to KR). We thank members of Dr. Van Zant’s lab (University of Kentucky) for technical consultations.

Abbreviations

- BSO

L-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- GAPDH

glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GSH

glutathione

- IGF

insulin-like growth factor

- IGFBP

insulin-like growth factor binding protein

- IL-1β

Interleukin-1β

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lee PD, Giudice LC, Conover CA, Powell DR. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1: recent findings and new directions. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1997;216:319–357. doi: 10.3181/00379727-216-44182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Duan C, Xu Q. Roles of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding proteins in regulating IGF actions. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2005;142:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Heemskerk VH, Daemen MA, Buurman WA. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and growth hormone (GH) in immunity and inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;10:5–14. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(98)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lang CH, Fan J, Cooney R, Vary TC. IL-1 receptor antagonist attenuates sepsis-induced alterations in the IGF system and protein synthesis. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:E430–437. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.270.3.E430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fan J, Molina PE, Gelato MC, Lang CH. Differential tissue regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I content and binding proteins after endotoxin. Endocrinology. 1994;134:1685–1692. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.4.7511091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lang CH, Pollard V, Fan J, Traber LD, Traber DL, Frost RA, Gelato MC, Prough DS. Acute alterations in growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor axis in humans injected with endotoxin. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:R371–378. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.1.R371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lee A, Whyte MK, Haslett C. Inhibition of apoptosis and prolongation of neutrophil functional longevity by inflammatory mediators. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;54:283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Silha JV, Murphy LJ. Insights from insulin-like growth factor binding protein transgenic mice. Endocrinology. 2002;143:3711–3714. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fan J, Wojnar MM, Theodorakis M, Lang CH. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I mRNA and peptide and IGF-binding proteins by interleukin-1. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:R621–629. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.270.3.R621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Lang CH, Nystrom GJ, Frost RA. Regulation of IGF binding protein-1 in hep G2 cells by cytokines and reactive oxygen species. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G719–727. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.3.G719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Lang CH. Stimulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 synthesis by interleukin-1beta: requirement of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3156–3164. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.9.7641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yang J, Anzo M, Cohen P. Control of aging and longevity by IGF-I signaling. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40:867–872. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ceda GP, Dall’Aglio E, Maggio M, Lauretani F, Bandinelli S, Falzoi C, Grimaldi W, Ceresini G, Corradi F, Ferrucci L, Valenti G, Hoffman AR. Clinical implications of the reduced activity of the GH-IGF-I axis in older men. J Endocrinol Invest. 2005;28:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Walston J, Fried LP. Frailty and the older man. Med Clin North Am. 1999;83:1173–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70157-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liddle C, Mode A, Legraverend C, Gustafsson JA. Constitutive expression and hormonal regulation of male sexually differentiated cytochromes P450 in primary cultured rat hepatocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;298:159–166. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lightle SA, Oakley JI, Nikolova-Karakashian MN. Activation of sphingolipid turnover and chronic generation of ceramide and sphingosine in liver during aging. Mech Ageing Dev. 2000;120:111–125. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Karakashian AA, Giltiay NV, Smith GM, Nikolova-Karakashian MN. Expression of neutral sphingomyelinase-2 (NSMase-2) in primary rat hepatocytes modulates IL-beta-induced JNK activation. Faseb J. 2004;18:968–970. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0875fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ. Analyzing JNK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Methods Enzymol. 2001;332:319–336. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(01)32212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rutkute K, Karakashian AA, Giltiay NV, Dobierzewska A, Nikolova-Karakashian MN. Aging in rat causes hepatic hyperresponsiveness to interleukin-1beta which is mediated by neutral sphingomyelinase-2. Hepatology. doi: 10.1002/hep.21777. (in press).

- [20].Beckman KB, Ames BN. The free radical theory of aging matures. Physiol Rev. 1998;78:547–581. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Vericel E, Narce M, Ulmann L, Poisson JP, Lagarde M. Age-related changes in antioxidant defence mechanisms and peroxidation in isolated hepatocytes from spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 1994;132:25–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00925671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hagen TM, Vinarsky V, Wehr CM, Ames BN. (R)-alpha-lipoic acid reverses the age-associated increase in susceptibility of hepatocytes to tert-butylhydroperoxide both in vitro and in vivo. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:473–483. doi: 10.1089/15230860050192251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Arvat E, Broglio F, Ghigo E. Insulin-Like growth factor I: implications in aging. Drugs Aging. 2000;16:29–40. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200016010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Janssen JA, Stolk RP, Pols HA, Grobbee DE, Lamberts SW. Serum free and total insulin-like growth factor-I, insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 Levels in healthy elderly individuals. Relation to self-reported quality of health and disability. Gerontology. 1998;44:277–280. doi: 10.1159/000022026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Janssen JA, Stolk RP, Pols HA, Grobbee DE, Lamberts SW. Serum total IGF-I, free IGF-I, and IGFB-1 levels in an elderly population: relation to cardiovascular risk factors and disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:277–282. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lo YY, Wong JM, Cruz TF. Reactive oxygen species mediate cytokine activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15703–15707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hagen TM, Yowe DL, Bartholomew JC, Wehr CM, Do KL, Park JY, Ames BN. Mitochondrial decay in hepatocytes from old rats: membrane potential declines, heterogeneity and oxidants increase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3064–3069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]