Abstract

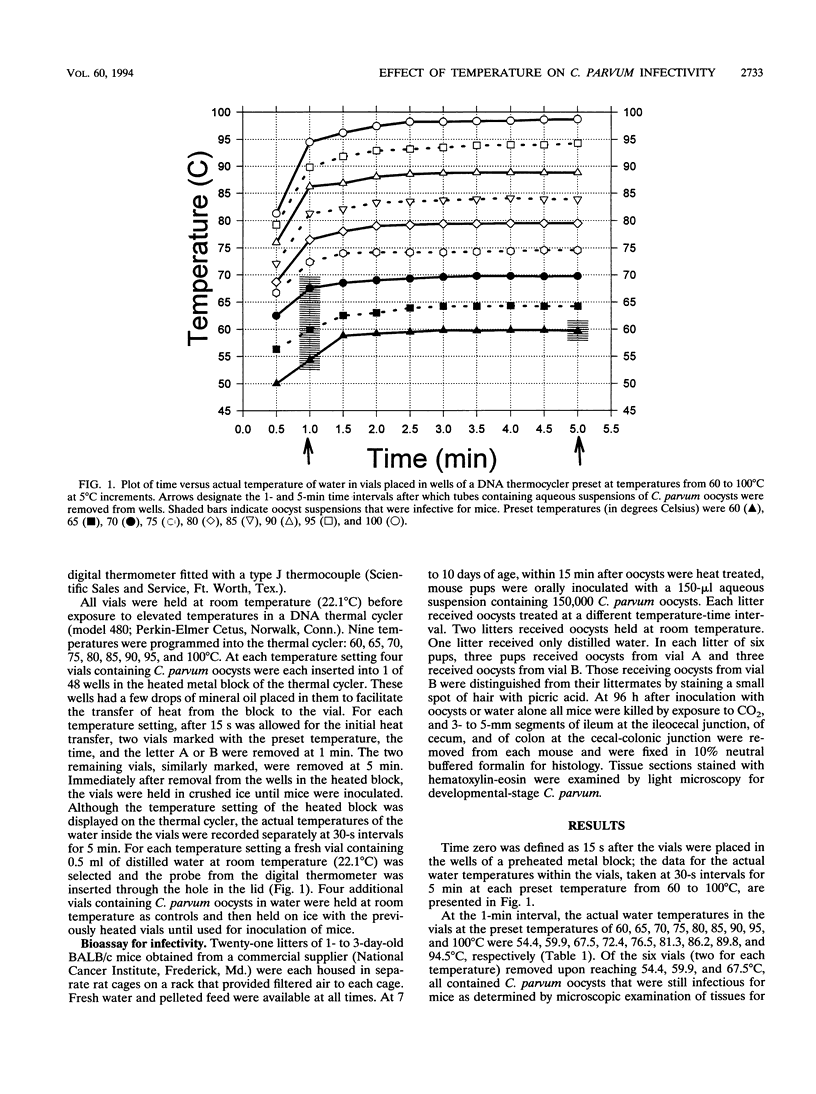

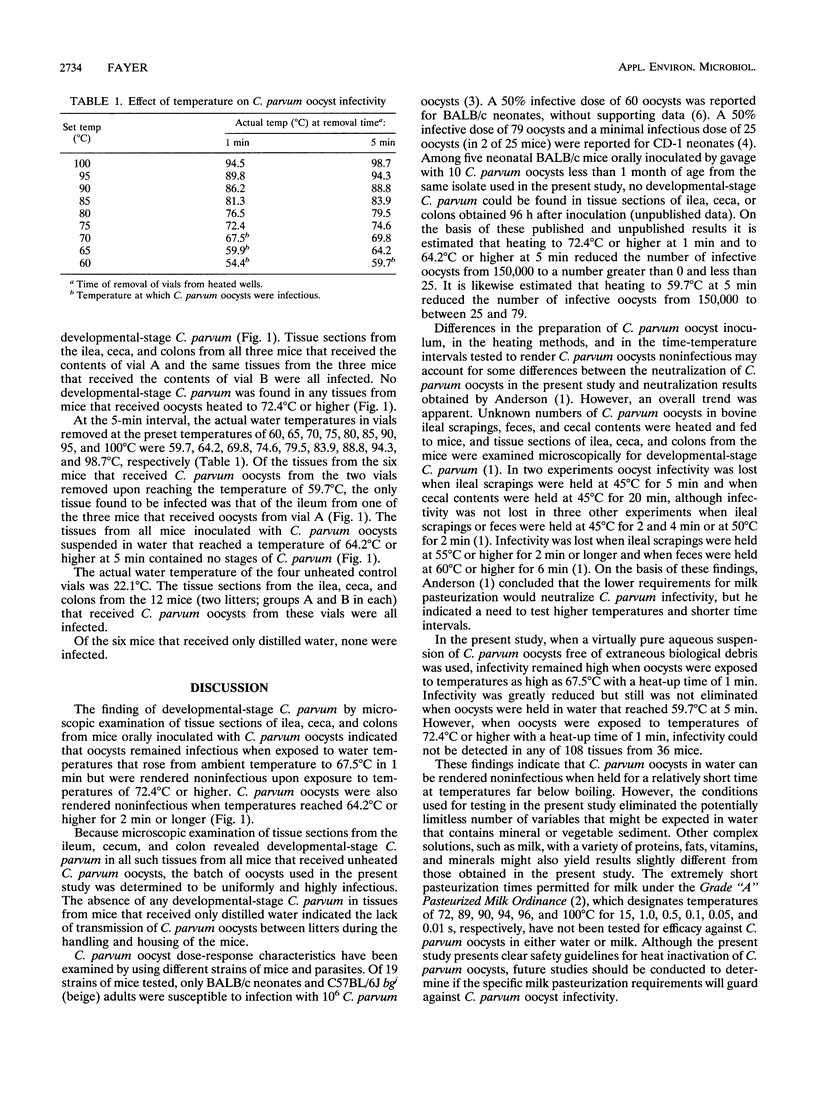

Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts suspended in 0.5 ml of distilled water were pipetted into plastic vials which were inserted into wells in the heated metal block of a thermal DNA cycler. Block temperatures were set at 5 degrees C incremental temperatures from 60 to 100 degrees C. At each temperature setting four vials containing C. parvum oocysts were placed into wells and held for 15 s before time was recorded as zero, and then pairs of vials were removed 1 and 5 min later. Upon removal, all vials were immediately cooled on crushed ice. Also, at each temperature interval one vial containing 0.5 ml of distilled water was placed in a well and a digital thermometer was used to record the actual water temperature at 30-s intervals. Heated oocyst suspensions as well as unheated control suspensions were orally inoculated by gavage into 7- to 10-day-old BALB/c mouse pups to test for infectivity. At 96 h after inoculation the ileum, cecum, and colon from each mouse were removed and prepared for histology. Tissue sections were examined microscopically. Developmental-stage C. parvum was found in all three gut segments from all mice that received oocysts in unheated water and in water that reached temperatures of 54.4, 59.9, and 67.5 degrees C at 1 min when vials were removed from the heat source. C. parvum was also found in the ileum of one of six mice that received oocysts in water that reached a temperature of 59.7 degrees C at 5 min.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson B. C. Moist heat inactivation of Cryptosporidium sp. Am J Public Health. 1985 Dec;75(12):1433–1434. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.12.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez F. J., Sterling C. R. Cryptosporidium infections in inbred strains of mice. J Protozool. 1991 Nov-Dec;38(6):100S–102S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch G. R., Daniels C. W., Black E. K., Schaefer F. W., 3rd, Belosevic M. Dose response of Cryptosporidium parvum in outbred neonatal CD-1 mice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993 Nov;59(11):3661–3665. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3661-3665.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilani R. T., Sekla L. Purification of Cryptosporidium oocysts and sporozoites by cesium chloride and Percoll gradients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987 May;36(3):505–508. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korich D. G., Mead J. R., Madore M. S., Sinclair N. A., Sterling C. R. Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990 May;56(5):1423–1428. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1423-1428.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. C., Herwaldt B. L., Craun G. F., Calderon R. L., Highsmith A. K., Juranek D. D. Surveillance for waterborne disease outbreaks--United States, 1991-1992. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1993 Nov 19;42(5):1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzipori S. Cryptosporidiosis in animals and humans. Microbiol Rev. 1983 Mar;47(1):84–96. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.1.84-96.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]