Doctors' postgraduate training needs to be completely reformed after the “sorry episode” of Modernising Medical Careers (MMC), John Tooke recommends in a highly critical report.

Professor Tooke's interim report, published on Monday, calls for the national computerised application system to be scrapped and for an end to the “run through” training introduced as part of MMC.

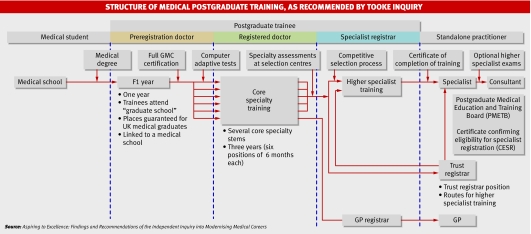

And he wants to see UK medical graduates automatically guaranteed a place on the first year of foundation training (F1). They would then, however, be expected to take a national examination at the end of the F1 year. This would give them a national rating that they would use to compete for training positions at a local level. Candidates from other European Union countries would also be able to apply for these posts, but not at the F1 stage.

However, the issue of medical graduates from outside the EU must also be dealt with, said Professor Tooke. “That's not to say that they have not made a fantastic contribution to the NHS in the past—and currently.”

But when it costs £200 000 (€290 000; $410 000) to £250 000 to train a UK medical graduate, said Professor Tooke, “some common sense has to prevail.”

Professor Tooke, dean of the Peninsula Medical School, was asked in April by the then health secretary, Patricia Hewitt, to investigate the failed implementation of the government's Modernising Medical Careers programme. His interim report will be followed by six weeks' consultation and then by a final report at the end of the year. His proposals, if accepted, could be fully implemented within two or three years, he believes.

Under his proposals, medical graduates who successfully complete their F1 year and gain entry to the medical register would then move into core specialty training, lasting three years. Trainee doctors would spend six sessions of six months each in one of a small number of defined core programmes (including medicine, surgery, and family medicine).

At the end of the core specialty training they would compete for the next round as a specialist registrar. After this round they would emerge as either specialists or GPs. Appointment to a consultancy might entail a further examination. The report recommends that GP training should be extended from three to five years.

He was highly critical of the way the Department of Health had managed the whole Modernising Medical Careers project, which was managed by two separate people, the chief medical officer and the director of workforce. To add to the problems, Professor Tooke said, neither the computerised medical training application service (MTAS) nor non-EU overseas medical graduates fell within the remit of either of the two senior managers.

But he refused to point the finger of blame at any single individual in the health department. “Our inquiry was not set up to name, shame, and blame,” he said at the press conference launching the report. “I can quite understand trainees wanting to blame someone. However, the simple answer is that this has been a systems failure. I'm not going to name names.”

Professor Tooke also highlighted numerous other failings in the implementation of the policy. These included a lack of a clear policy objective for postgraduate medical education; no consensus on the role of doctors at the various stages in their careers, thus hampering workforce planning; no policy on the potential massive increase in the number of trainees; and poor relationships between academia and the NHS.

In particular, he singled out the fact that medical education is regulated at undergraduate level by the General Medical Council and at postgraduate level by the Postgraduate Medical Education Training Board. He says that the board's role should be taken over by the GMC. Graeme Catto, president of the GMC, has welcomed that proposal. He said, “There is a very strong case for consolidating responsibility for all stages of medical education and training under the GMC.”

Professor Tooke also shed light on the failings of MTAS. “It was commissioned late,” he said, adding that the specification changed half way through the process, although what was delivered did meet the requirements of the contract. “Many of the problems were through the rushed implementation,” he said. “Why, given the importance of this project, would you want to rush it? The process was not adequately managed.”

He also said that the government should urgently resolve the non-consultant grade contract and called for the role to be “de-stigmatised.”

(See News doi: 10.1136/bmj.39363.658056.59 and Editorial doi: 10.1136/bmj.39364.512685.80.)

Aspiring to Excellence: Findings and Recommendations of the Independent Inquiry into Modernising Medical Careers is available at www.mmcinquiry.org.uk.