Abstract

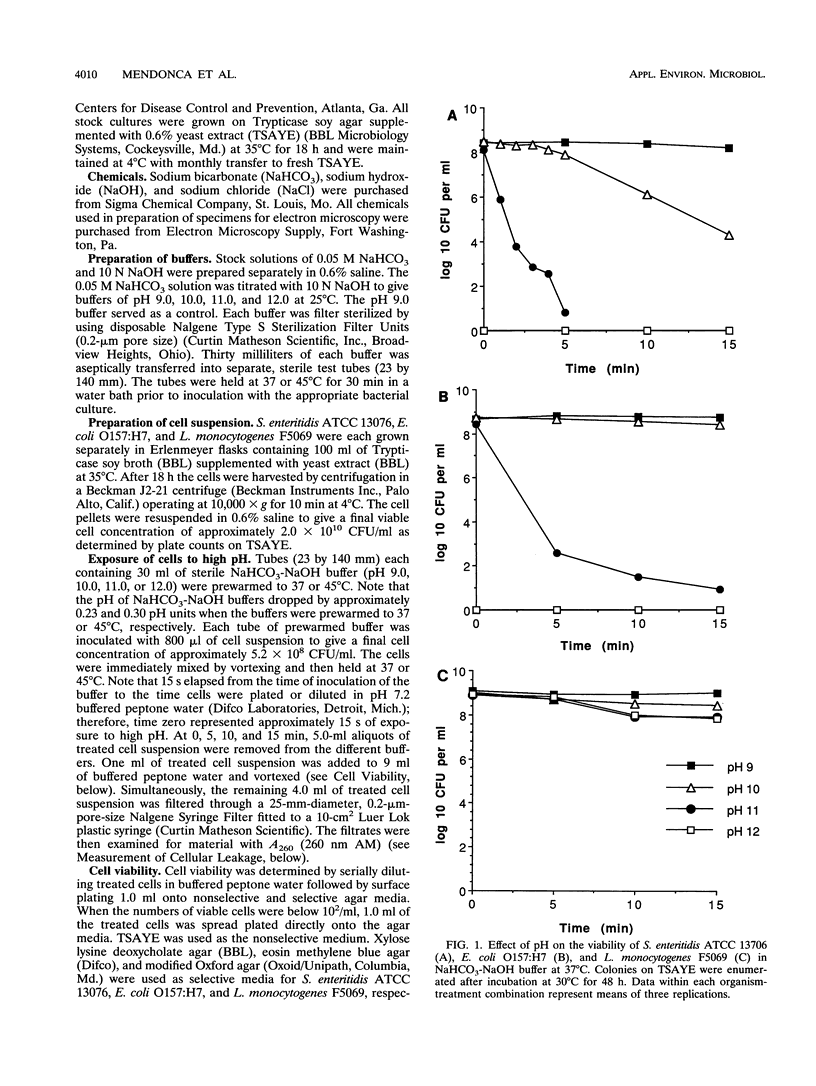

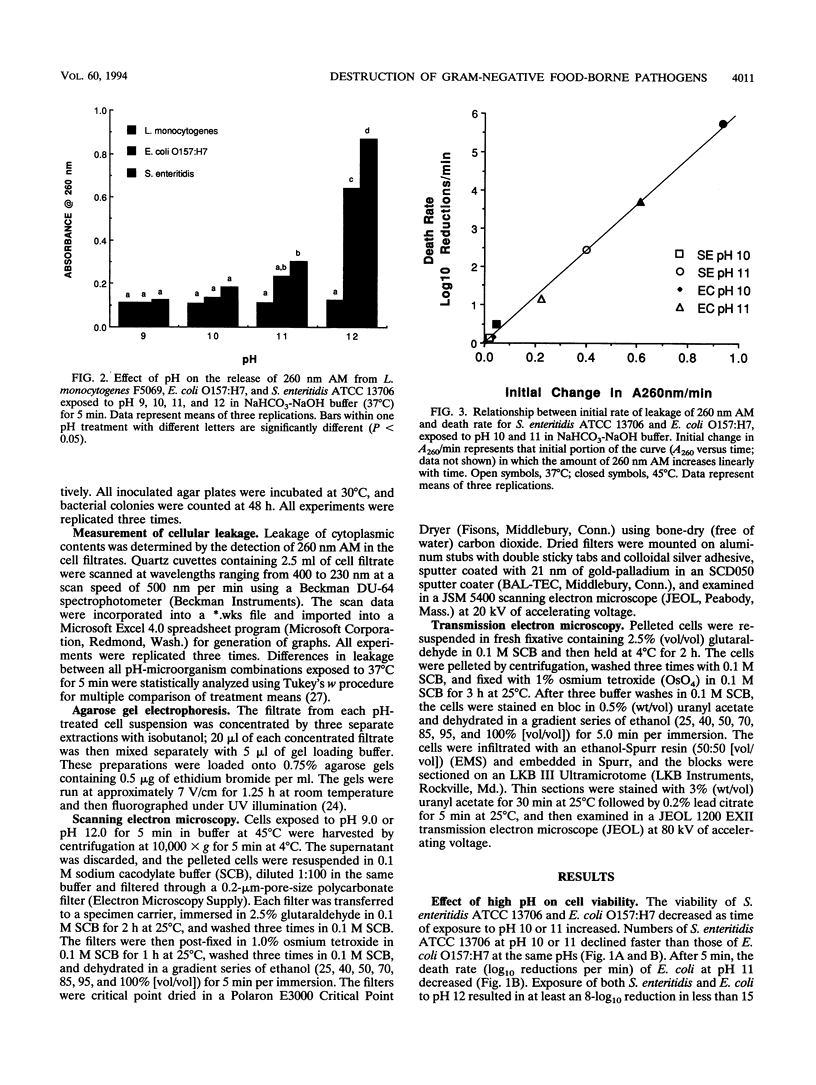

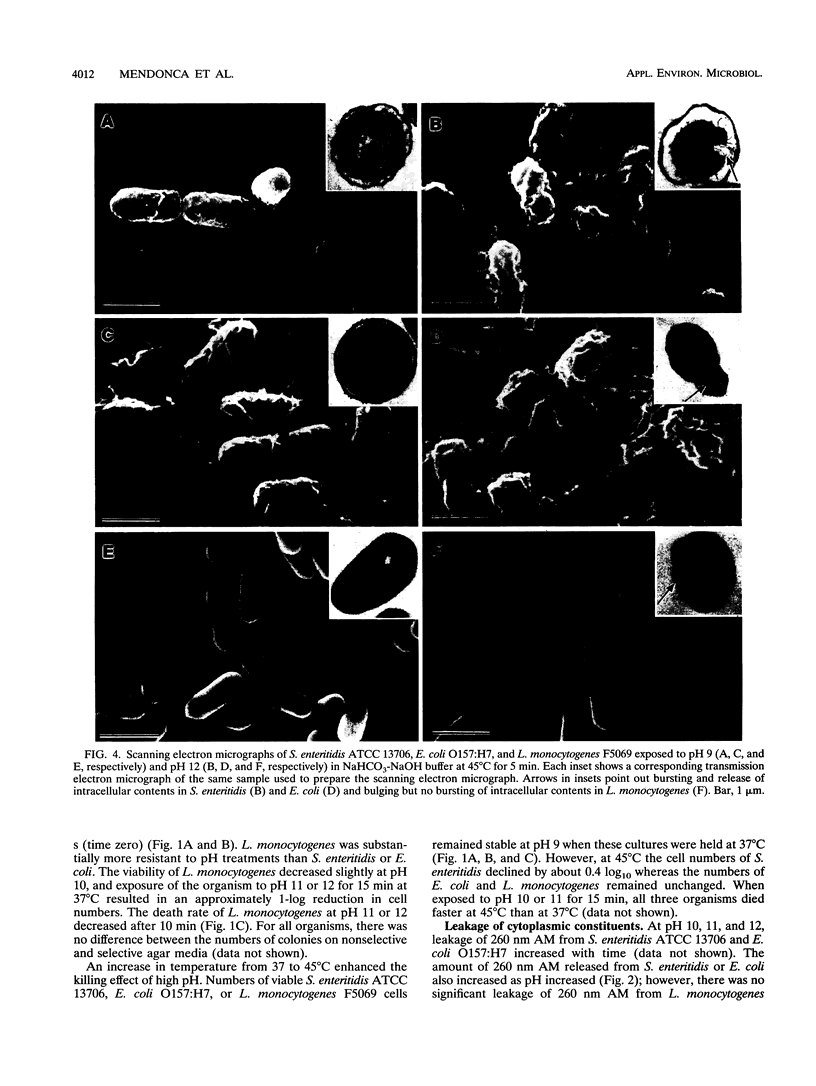

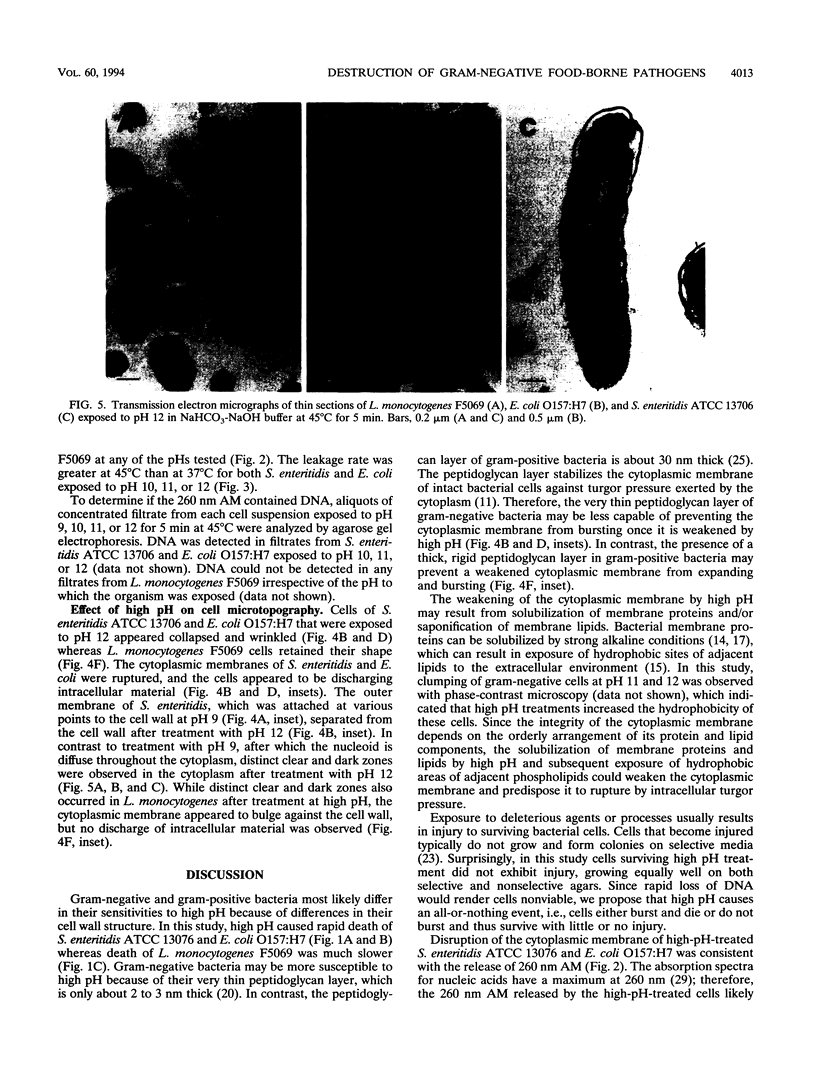

High pH has been shown to rapidly destroy gram-negative food-borne pathogens; however, the mechanism of destruction has not yet been elucidated. Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enteritidis ATCC 13706, and Listeria monocytogenes F5069 were suspended in NaHCO3-NaOH buffer solutions at pH 9, 10, 11, or 12 to give a final cell concentration of approximately 5.2 x 10(8) CFU/ml and then held at 37 or 45 degrees C. At 0, 5, 10, and 15 min the suspensions were sterilely filtered and each filtrate was analyzed for material with A260. Viability of the cell suspensions was evaluated by enumeration on nonselective and selective agars. Cell morphology was evaluated by scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy. A260 increased dramatically with pH and temperature for both E. coli and S. enteritidis; however, with L. monocytogenes material with A260 was not detected at any of the pHs tested. At pH 12, numbers of E. coli and S. enteritidis decreased at least 8 logs within 15 s, whereas L. monocytogenes decreased by only 1 log in 10 min. There was a very strong correlation between the initial rate of release of material with A260 and death rate of the gram-negative pathogens (r = 0.997). At pH 12, gram-negative test cells appeared collapsed and showed evidence of lysis while gram-positive L. monocytogenes did not, when observed by scanning and transmission electron microscopy. It was concluded that destruction of gram-negative food-borne pathogens by high pH involves disruption of the cytoplasmic membrane.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cherrington C. A., Hinton M., Mead G. C., Chopra I. Organic acids: chemistry, antibacterial activity and practical applications. Adv Microb Physiol. 1991;32:87–108. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csonka L. N. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiol Rev. 1989 Mar;53(1):121–147. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.121-147.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle M. P. Reducing foodborne disease--what are the priorities? Nutr Rev. 1993 Nov;51(11):346–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1993.tb03764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan C. L., Labbe R. G., Reich R. R. Germination of heat- and alkali-altered spores of Clostridium perfringens type A by lysozyme and an initiation protein. J Bacteriol. 1972 Feb;109(2):550–559. doi: 10.1128/jb.109.2.550-559.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsohn M. K., Lehman M. M., Jacobsohn G. M. Cell membranes and multilamellar vesicles: influence of pH on solvent induced damage. Lipids. 1992 Sep;27(9):694–700. doi: 10.1007/BF02536027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe R. G., Reich R. R., Duncan C. L. Alteration in ultrastructure and germination of Clostridium perfringens type A spores following extraction of spore coats. Can J Microbiol. 1978 Dec;24(12):1526–1536. doi: 10.1139/m78-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird J. M., Bartlett F. M., McKellar R. C. Survival of Listeria monocytogenes in egg washwater. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991 Feb;12(2-3):115–122. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. J., Corry J. E. Survey of the incidence of Listeria monocytogenes and other Listeria spp. in experimentally irradiated and in matched unirradiated raw chickens. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991 Feb;12(2-3):257–262. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURRAY R. G., STEED P., ELSON H. E. THE LOCATION OF THE MUCOPEPTIDE IN SECTIONS OF THE CELL WALL OF ESCHERICHIA COLI AND OTHER GRAM-NEGATIVE BACTERIA. Can J Microbiol. 1965 Jun;11:547–560. doi: 10.1139/m65-072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson J., Southam G. G., Holley R. A. Survival and transport of bacteria in egg washwater. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987 Sep;53(9):2060–2065. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.9.2060-2065.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shockman G. D., Barrett J. F. Structure, function, and assembly of cell walls of gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1983;37:501–527. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.37.100183.002441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer D. W., Boyd G. Elimination of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in meats by gamma irradiation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993 Apr;59(4):1030–1034. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1030-1034.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulitzur S. Rapid determnation of DNA base composition by ultraviolet spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972 Jun 22;272(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(72)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Marel G. M., van Logtestijn J. G., Mossel D. A. Bacteriological quality of broiler carcasses as affected by in-plant lactic acid decontamination. Int J Food Microbiol. 1988 Feb;6(1):31–42. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(88)90082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]