Abstract

InhA, the enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase (ENR) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is one of the key enzymes involved in the type II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway of M. tuberculosis. We report here the discovery, through high-throughput screening, of a series of arylamides as a novel class of potent InhA inhibitors. These direct InhA inhibitors require no mycobacterial enzymatic activation and thus circumvent the resistance mechanism to antitubercular prodrugs such as INH and ETA that is most commonly observed in drug-resistant clinical isolates. The crystal structure of InhA complexed with one representative inhibitor reveals the binding mode of the inhibitor within the InhA active site. Further optimization through a microtiter synthesis strategy followed by in situ activity screening led to the discovery of a potent InhA inhibitor with in vitro IC50 = 90 nM, representing a 34-fold potency improvement over the lead compound.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, InhA inhibition, enoyl Co-A reductase inhibition, high throughput screening, parallel synthesis

1. Introduction

The NADH-dependent enoyl-ACP reductase encoded by the Mycobacterium gene inhA has been validated as the primary molecular target of the frontline antitubercular drug isoniazid (INH).1 Recent studies demonstrated that InhA is also the target for the second line antitubercular drug ethionamide (ETA).2 InhA catalyzes the reduction of long-chain trans-2-enoyl-ACP in the type II fatty acid biosynthesis pathway of M. tuberculosis. Inhibition of InhA disrupts the biosynthesis of the mycolic acids that are central constituents of the mycobacterial cell wall.3 As a prodrug, INH must first be activated by the mycobacterial catalase-peroxidase KatG into its acyl radical active form. The adduct resulting from covalent binding of the activated INH to the InhA cosubstrate NADH, or its oxidation product NAD+, functions as a potent InhA inhibitor.4 Similarly, a comparable NAD adduct of ETA has been identified and shown to be an effective InhA inhibitor, although ETA is activated by EtaA, a flavoprotein monooxygenase, rather than by KatG.2 INH has been widely applied as the frontline agent for the treatment of tuberculosis for the past 40 years. Clinical studies indicate that the majority of these prodrug (INH, ETA)-resistant clinical isolates arise from KatG or EtaA-associated mutations.5,6 Therefore, inhibitors targeting InhA directly without a requirement for activation would be promising candidates for the development of agents against the ever increasing threat from drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains. Several series of direct InhA inhibitors, including pyrazole derivatives, indole-5-amides7 and alkyl diphenyl ethers8 have been identified recently that show both in vivo and in vitro activity. We also recently reported the discovery and optimization of pyrrolidine carboxamides as a novel series of direct InhA inhibitors.9 In the current study, we report the discovery of another series of amides during the high-throughput screening campaign for novel direct InhA inhibitors and a follow up optimization of the series via a microtiter synthetic strategy and in situ screening.

2. Results and Discussion

To identify novel inhibitors targeting the M. tuberculosis InhA, we performed a high-throughput screen of a chemical diversity library of 30,000 compounds from the Bay Area Screening Center based on the approach described previously.9 Compounds exhibiting at least 50% InhA inhibitory activity at 30 μM were labeled as hit compounds. Thirty compounds were identified and reconfirmed by IC50 determination employing the authentic solid compounds. The potencies of each compound in the presence and absence of 0.01% X-Triton were also compared to eliminate potential false positive hits, also known as promiscuous inhibitors, which result from the non-specific formation of aggregates that sequester and inhibit the enzyme.10,11 These 30 hit compounds can be grouped into 13 structurally diverse classes. The largest class is the arylamide series of compounds, all of which contain a piperazine or piperidine as the core structure (Table 1). Among the arylamides, a4 is the most potent compound identified in the initial screen with IC50 = 3.07 μM. A review of the substructure query of the 30,000 compounds screened revealed the presence of a number of inactive arylamide analogues in the initial high-throughput screen. Together, the data suggests that compounds with a single electron-withdrawing substituent at the meta-position of ring B are the most potent inhibitors. To carry out a preliminary exploration of the structure-activity relationships (SAR) of these compounds, a series of compounds was selected and purchased on the basis of traditional medicinal chemistry principles. Their inhibition of InhA activity was then determined by IC50 measurements according to previously reported protocols.

Table 1.

| Compd | X | n | R1 | R2 | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a1 | N | 0 | H | H | 38.86 ± 1.35 |

| a2 | N | 0 | 4-CH3 | H | 16.64 ± 0.49 |

| a3 | N | 0 | 4-CH3 | 3-CF3 | 6.26 ± 0.33 |

| a4* | N | 0 | 4-CH3 | 3-Cl | 3.07 ± 0.48 |

| a5 | N | 0 | 3-CH3 | 3-Cl | 9.43 ± 0.80 |

| a6* | N | 0 | 3-CH3 | 4-NO2 | 15.47 ± 1.52 |

| a7 | N | 0 | 3,4-Me2 | 3-Cl | 0.99 ± 0.03 |

| a8 | N | 0 | 3,4-Me2 | 3-CF3 | 1.85 ± 0.08 |

| a9 | N | 0 | 4-iPr | 3-Cl | >100 |

| a10 | N | 0 | 4-t-Bu | 3-Cl | >100 |

| a11 | N | 0 | 4-t-Bu | 3-CF3 | >100 |

| a12 | N | 0 | 4-t-Bu | 4-CH3, 3-Cl | >100 |

| a13* | N | 0 | 2-F | 3-Cl | 13.87 ± 1.03 |

| a14* | N | 0 | 4-F | 3-Cl | 9.74 ± 0.62 |

| a15* | N | 0 | 3-Cl | 3-Cl | 6.73 ± 0.27 |

| a16* | N | 0 | 3,4-Cl2 | 3-Cl | 6.05 ± 0.58 |

| a17* | N | 0 | 3,4-Cl2 | H | 17.62 ± 1.24 |

| a18* | N | 1 | H | H | 31.50 ± 1.65 |

| b1* | C | 1 | 3-Cl | H | 7.74 ± 0.25 |

| b2* | C | 1 | 2-F | H | 14.11 ± 0.42 |

| b3* | C | 1 | 4-CH3 | H | 5.16 ± 0.45 |

| b4* | C | 1 | 3-CH3 | H | 7.39 ± 0.38 |

Compound identified in the initial round of high-throughput screening

SAR

The InhA inhibition activities of the arylamide series of compounds are summarized in Table 1. Compound a1, without any substituent on either of the phenyl rings, displayed an IC50 of ∼ 39 μM and serves as the standard for potency comparison. The activity of a2 improved more than two-fold when a -CH3 was introduced at the para-position of phenyl ring A. The presence of additional electron-withdrawing groups (3-Cl, a3; 3-CF3, a4) on ring B greatly increased the potency, resulting in IC50 values of 3.07 and 6.26 μM, respectively. The electron-withdrawing nature of the group at the meta-position of ring B is an important determinant of activity, as many analogues with para- or ortho-substituents on ring B were found to be inactive in the high-throughput screen (percentage of inhibition less than 10% when tested at 30 μM, data not shown). Replacement of the 4-CH3 on ring A with a 3-CH3 led to a 3-fold decrease in potency (a5). The activity was further diminished when the 3-Cl on ring B was simultaneously replaced with a 4-NO2 (a6). Compounds a7 and a8 exhibited the best InhA inhibition activity in this series with IC50 values of 0.99 and 1.85 μM, respectively, indicating that the presence of dual methyl groups was beneficial and improved potency. However, the further introduction of bulky substituents (tert-butyl or iso-propyl) at the para-position of phenyl ring A abolished activity (a9-a12), indicating that for optimal activity there is a size limit for substituents at the 4-position of ring A. Such bulky substituents may interfere with binding in the active site despite the presence of electron-withdrawing group(s) at the meta-position of ring B. No further improvement was observed when the 4-CH3 on ring A was replaced with electron-withdrawing groups such as 2-F, a13; 4-F, a14; 3-Cl, a15; or 3,4-Cl2, a16. The fact that the activity of a16 is nearly 3-fold that of a17 confirmed the importance for potency of a 3-Cl substituent on ring B. Another series of analogues was also identified in the high-throughput screen and was confirmed by IC50 measurements in which rings B and C were separated by a carbon atom (a18) and the piperazine Ring C was replaced by a piperidine (b1-b4). The insertion of one carbon atom had little effect on the activity (a18) and all the piperidine derivatives exhibited similar potency with IC50 values ranging from 5-14 μM.

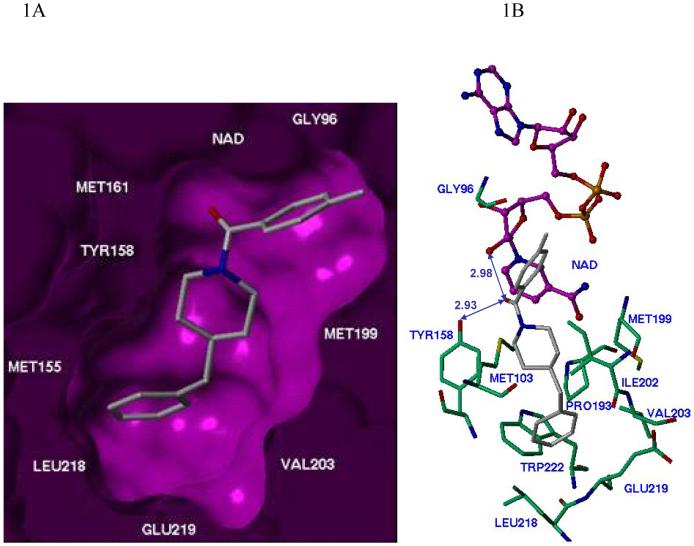

Crystallographic Analysis of the InhA Inhibitor Binding Site

The crystal structures of InhA-inhibitor complexes incubated with NADH were solved for one of the piperidine compounds b3 (Figure 1). Consistent with our modeling prediction and all known enoyl reductase (ENR)-inhibitor complexes, we observed a signature hydrogen-bond network, a critical feature responsible for formation of the substrate/inhibitor-enoyl ACP reductase complex.8,9,12-16 In the complex, the amide carbonyl group oxygen is hydrogen-bonded to the 2′-hydroxyl moiety of the nicotinamide ribose and the hydroxyl group of Tyr158 (Figure 1B), one of the catalytic residues in the InhA active site. The unsubstituted phenyl (ring B) also fit nicely into the binding pocket and interacted with the hydrophobic residues of Phe149, Pro193, Leu218 and Val203. In agreement with the SAR of the a series (Table 1), the introduction of a -Cl or -CF3 at the meta-position would strenghthen the possible interactions with these sidechains, resulting in the observed increased potency. In addition, it looks like there is still space to expand the size of ring B to fill the void between the inhibitor and active site residues at the bottom of the binding pocket (Figure 1A). The introduction of larger hydrophobic substituents in the place of ring B might provide more hydrophobic contacts between the inhibitor and hydrophobic residues. The van der Waal’s interactions between the methylated phenyl ring A of b3 and Gly96 and the nicotinamide part of NAD further contribute to stabilization of the inhibitor-InhA complex.

Figure 1. Inhibitor b3 bound to the active site of the M. tuberculosis InhA.

A, Purple molecular surface shows the active site cleft in which compound b3 (in capped stick model) binds. B, Details of InhA-b3 interactions. Key residues within a 4.5 Å sphere of the b3 binding pocket are shown. The oxygen on the carbonyl group of the amide makes hydrogen-bonding interactions with the 2′-hydroxyl moiety of the nicotinamide ribose and the hydroxyl group of Tyr158 (blue line). C. A different perspective of inhibitor b3 bound in the active site of M. tuberculosis InhA further illustrating the key contacts of the inhibitor with the protein. Single molecules in the structure are denoted by an x.

Microtiter Synthesis and In Situ Screening of InhA Inhibitors

Over the last decade the concept of privileged structures has emerged as a successful approach in medicinal chemistry for the discovery and optimization of novel bioactive molecules.17 Privileged structures are defined as molecular scaffolds that are frequently found in molecules that are active at multiple different receptors. Such substructures usually represent the core element of a molecule and make up a significant portion of its total mass. It is believed that the privileged fragment provides the scaffold for a particular target whereas the specificity of the compound is determined by the various substituents appended to it in the derivatives. In combinatorial synthesis, the application of the versatile chemical motif provides an effective approach for the rapid generation of high quality lead compounds suitable for further development.17

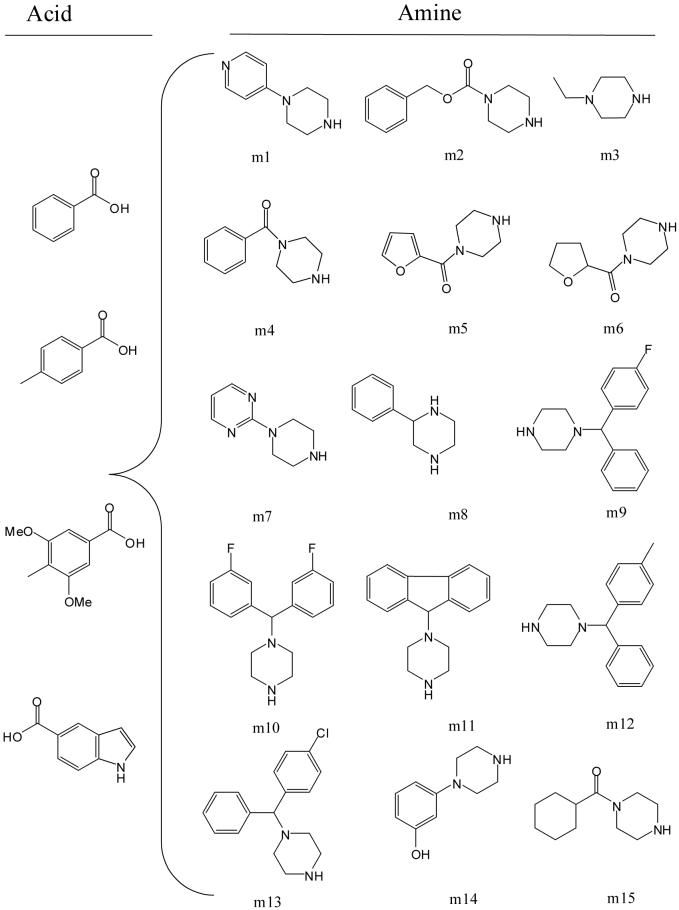

Preliminary SAR studies of the hit compounds identified suggested that a piperazine is the key scaffold for this series of InhA inhibitors. Compounds with the piperazine scaffold exhibited the best inhibitory activity among the initial commercially available compounds tested (a4, IC50 = 3.07 μM). The piperazine scaffold has been recognized as one of the privileged structures in drug discovery and is frequently found in biologically active compounds across a number of different therapeutic areas, including antifungals, antidepressants, antivirals, and serotonin receptor (5-HT) agonists/antagonists.18 To further explore the effect of various amines on the potency of the arylamide series, we prepared an amide library focusing on diversification of the amine while retaining the key piperazine scaffold intact. A total of 14 commercially available amine building blocks were selected from the Sigma piperazine privileged structures database. Given the hydrophobic contact between the phenyl group (ring B) and hydrophobic residues (Leu218, Val203) in the InhA-inhibitor complex (Figure 1), amines bearing multiple bulky ring structures were included among the 14 amines in order to increase the potential hydrophobic contacts (Figure 2). For the carboxylic acid portion, benzoic acid and 3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid were included in addition to 4-methylbenzoic acid, the most favorable substituent based on the preliminary SAR studies.

Figure 2.

Structures of the carboxylic acids and amines utilized in the microtiter focused library synthesis.

An expedient diversity-oriented synthesis was recently reported using microtiter plates for in situ screening of enzyme inhibitors.19-21 The products of the small-scale parallel syntheses were subsequently assayed for enzyme inhibition without product isolation and purification. This approach provided an efficient way for rapid identification and optimization of potent enzyme inhibitors as long as a high-yield organic reaction in water or a water-miscible solvent is accessible. We applied the same strategy for our focused microtiter library by employing an amide-forming reaction with the peptide coupling reagent 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) and the base N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Since the amide product combining indole carboxylic acid and amine m11 was known as an effective InhA inhibitor, the indole carboxylic acid was included in the focused amide library to serve as a positive control for the subsequent in situ enzyme inhibition screen. The reaction was carried out at room temperature and monitored by TLC. The identity of the desired product in each well was determined by LC-MS. Out of 60 designed amide compounds, 56 desired products were successfully generated and confirmed as the major products. No product was observed for amine m3 with benzoic acid or indole carboxylic acid. Amines m1 and m6 also did not react with benzoic acid or 3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid, respectively. After dilution of the reaction mixture with assay buffer, each product was directly tested without further purification at a final concentration of 15 μM in the 96-well plate format inhibition assay. The acceptable concentrations of the solvent DMF, coupling reagent HBTU, and base DIEA in the assay mixture were predetermined to minimize the solvent effect on InhA activity.

Among the 56 desired amides, 12 compounds exhibited at least 65% InhA inhibitory activity when tested at a concentration of 15 μM, among them 3 compounds inhibited 90% of InhA activity (p1, p2, p3, Table 2). All these 12 potent compounds are derivatives with the introduction of appropriate polyaromatic moieties appended to the piperazine ring C, which indicated the importance of hydrophobic interactions for the potency of InhA inhibitors. Three compounds (p1, p2, p3) with fused multiple ring structures exhibited submicromolar IC50 values. The positive control compound p3 inhibited 94% InhA activity when tested at 15 μM and its IC50 was determined to be 0.2 μM, which is close to the reported value of 0.16 μM,7 thus validating the in situ screening strategy. However, it is noteworthy that all the 3,5-dimethoxybenzoic acid derivatives were inactive despite the presence of hydrophobic multiple ring structures, suggesting that the presence of dual meta-substituents on ring A suppressed activity. Six compounds showing at least 80% InhA inhibition were individually synthesized, purified by preparative TLC, and further characterized by NMR and LC-MS. IC50 values were calculated from plots of enzyme activity versus the log of the inhibitor concentration using the GraFit IC50 four-parameter fit software (GraFit 4.021, Erithacus). The best compound identified so far exhibited an IC50 of 90 nM, representing a 34-fold improvement in the potency of the lead compound a4.

Table 2.

InhA inhibition activities of arylamide compounds identified by microtiter synthesis and in situ screening

| Structure | ID | Inhibition % (15 μM) | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

p1 | 99 | 0.40 ± 0.02 |

|

p2 | 97 | 0.09 ± 0.00 |

|

p3 | 94 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

|

p4 | 84 | 1.04 ± 0.04 |

|

p5 | 83 | 1.89 ± 0.11 |

|

p6 | 81 | 2.04 ± 0.08 |

|

p7 | 81 | ND* |

|

p8 | 81 | ND |

|

p9 | 77 | ND |

|

p10 | 74 | ND |

|

p11 | 74 | ND |

|

p12 | 67 | ND |

ND = not determined

Antibacterial Activity

Selected compounds with the best enzyme inhibitory activities were submitted for evaluation of M. tuberculosis growth inhibition in culture. The determinations of the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) against M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv indicated modest antibacterial activity. The majority of the compounds exhibited MIC above 125 μM. Compound p4 displayed the best activity with a MIC value of 62.5 μM, and compounds p6 and a6 had MIC values of 125 μM. These results suggest that these inhibitors do not yet have the optimal membrane permeability that might be achieved by a correct balance between the lipophilicity of the substituents on ring C and the hydrophilicity of the potentially protonated piperazine on ring B. It is also possible that these compounds are actively extruded from the bacterial cell by efflux pumps.

3. Conclusion

We have identified arylamides as a novel class of InhA inhibitors through high-throughput screening. On the basis of the preliminary SAR studies and the crystal structure of one InhA-inhibitor complex, a focused library was synthesized that diversified the amines fragment but retained the piperazine privileged structure. The application of an expedient microtiter library synthesis followed by in situ screening enabled the rapid discovery of more potent InhA inhibitors. The best inhibitor exhibited an IC50 of 90 nM, a 34 fold gain in potency over the initial lead compound.

4. Experimental

4.1. Materials and general methods

Reagents and solvents were used as obtained from commercial suppliers without further purification. Column chromatography was carried out on Merck silica gel 60 (230-400 mesh). 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Gemini 400 (400 MHz) spectrometer. Mass spectra were recorded using an LC/MS system consisting of a Waters 1100 HPLC instrument and a Waters ZQ mass detector (ESI positive). Hits identified in the high-throughput screen were purchased from Chembridge and ChemDIV Inc. (San Diego, CA). All other buffer salts (reagent grade or better), solvents (HPLC grade or better), and Column chromatography was carried out on Merck silica gel 60 (230-400 mesh). 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian Gemini 400 (400 MHz) spectrometer. Chemical shifts are given in ppm with tetramethylsilane (organic solvents), and coupling constants (J) are given in Hertz (Hz). Mass spectra were recorded using an LC/MS system consisting of a Waters 1100 HPLC instrument and a Waters ZQ mass detector (ESI positive). Purity was determined with a Hewlett-Packard HPLC (1090C) system. Normal phase: Alltech silica, 4.6 × 250 mm column (5 μm); HPLC1, 90:10 v/v; over 20 min; flow rate, 1.0 mL/min; wavelength, 254 nm. Reverse phase: Varian, Dynaman microsorb 100-5 C18, 250 × 4.6 mm column; HPLC2, 60:40 v/v MeOH:H2O over 2 min, followed by 60:40-5:10 v/v MeOH:H2O over 8 min, then hold at 95/5 v/v CH3CN:H2O over 10 min; flow rate, 1.0 mL/min; wavelength, 230/254 nm.

4.2. General procedure for microtiter library synthesis and follow up in situ screening

The synthesis of microtiter library compounds was performed in 96-well plates. A solution of pyrrolidinecarboxylic acid (40 μL, 100 mM, 1 equiv) in DMF was added to each well followed by 22 μL of HBTU (200 mM, 1.1 equiv) and 8 μL of DIEA (1 M, 2 equiv). Finally, the corresponding amine (40 μL, 100 mM, 1 equiv) in DMF was added and the reaction plate was shaken on the Molecular Device SPECTRAmax PLUS 384 microreader for 2 h at 45 ° C. The reaction was monitored by TLC and the identity of the major product in each well was confirmed by LC-MS. Once the reaction was completed, the products were diluted, transferred to the assay plate and tested. DMF (<0.5% in the final assay) was used in the place of DMSO in the control and the final testing concentration of each product was 15 μM (assuming a 100% yield in the reaction).

4.3. General procedure for synthesis of the amide, as exemplified by the synthesis of (4-(9H-fluoren-9-yl) piperazin-1-yl)-(4-methylbenzyl)-methanone (p1)

To a solution of amine (25.1 mg, 0.1 mmol) and acid (15 mg, 0.11 mmol) in 3 mL of dry DMF, HBTU (50 mg, 0.13 mmol) and DIEA (50 μL, 0.3 mmol) were added at 23 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred for 5 h and was then quenched by the addition of brine and extracted three times with EtOAc. The organic layers were combined and washed sequentially with 1 N HCl, saturated aqueous NaHCO3, and brine before being dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by preparative TLC with CH2Cl2/MeOH (40:1 v/v) to give the product (32.1 mg) in 87% yield: LC-MS ([M + H]+) calcd for [C25H24N2OH]+ 369.19, found 369.19. 1H NMR (400 Mhz CD3OD) δ 7.70 (dd, 2H), 7.60 (dd, 2H), 7.31-7.36 (m, 2H), 7.16-7.26 (m, 6H), 4.83 (s,1H), 3.60-3.80 (bs, 2H), 3.28-3.42 (bs, 2H), 2.60-2.76 (bs, 2H), 2.36-2.48 (bs, 2H), 2.34 (s, 3H). HPLC1: 6.91 min, purity >99%. HPLC2: 16.98 min, purity >95%. Compounds p2, p4, p5, p6 were prepared following the same protocol.

4.3.1. [4-(9H-fluoren-9-yl) piperazin-1-yl]-benzyl-methanone (p2)

yield 83%. LC-MS ([M + H]+) calcd for [C24H22N2OH]+ 355.17, found 355.17. 1H NMR (400 Mhz CDCl3) δ 7.68 (d, 2H), 7.28-7.42 (m, 9H), 4.84 (s,1H), 3.68-3.88 (bs, 2H), 3.24-3.42 (bs, 2H), 2.72-2.92 (bs, 2H), 2.32-2.52 (bs, 2H). HPLC1: 6.56 min, purity >99%. HPLC5: 17.47 min, purity >97%.

4.3.2. (4-(Bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl)piperazin-1-yl)-(1H-indole-5-carbonyl)-methanone (p4)

yield 82%. LC-MS ([M + H]+) calcd for [C26H23F2N3OH]+ 432.18, found 431.18. 1H NMR (400 Mhz CD3OD) δ 7.58-7.60 (m, 1H), 7.32-7.43 (m, 5H), 7.25-7.28 (d, 1H), 7.07-7.13 (dd, 1H), 6.92-7.02 (m, 4H), 6.47 (d, 1H), 4.30 (s,1H), 3.50-3.90 (bs, 4H), 2.30-2.50 (bs, 4H). HPLC1: 11.95 min, purity >99%. HPLC2: 13.53 min, purity >96%.

4.3.3. (4-(Bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl)piperazin-1-yl)- )-(4-methylbenzyl)-methanone (p5)

yield 86%. LC-MS ([M + H]+) calcd for [C25H24F2N2OH]+ 406.19, found 406.19. 1H NMR (400 Mhz CD3OD) δ 7.34-7.46 (m, 4H), 7.16-7.28 (m, 4H), 6.92-7.06 (m, 4H), 4.32 (s, 1H), 3.30-3.70 (m, 4H), 2.20-2.50 (m, 4H), 2.32 (s, 3H). HPLC1: 4.84 min, purity >99%. HPLC2: 13.15 min, purity >97%.

4.3.4. (4-(Bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl)piperazin-1-yl)-benzyl-methanone (p6)

yield 91%. LC-MS ([M + H]+) calcd for [C24H22F2N2OH]+ 393.17, found 393.17. 1H NMR (400 Mhz CD3OD) δ 7.35-7.47 (m, 9H), 6.97-7.09 (m, 4H), 4.35 (s,1H), 3.70-3.82 (bs, 2H), 3.38-3.52 (bs, 2H), 2.30-2.50 (bs, 4H). HPLC1: 4.53 min, purity >99%. HPLC2: 14.15 min, purity >98%.

4.4. InhA enzyme assay

InhA and its substrate 2-trans-octenoyl-CoA (OCoA) were prepared as described previously.9 The high-throughput screening of InhA Inhibitors was carried out using the endpoint assay as described previously.9 IC50 values were determined in 96-well plates by serial 2-fold dilutions with DMSO of each inhibitor. The final concentration of DMSO in the final assay was 1%. The IC50values were determined using at least 8 concentrations, with each concentration assayed in triplicate under saturating substrate conditions. The concentrations of other components in the assay were as follows: NADH 250 μM (stock 1 mM, 50 μL, Km 7.6 μM); InhA 20 nM (stock 80 nM, 50 μL). OCoA 500 μM (stock 2 mM, 50 μL, Km 467 μM) was prepared freshly by dissolving the flaky solid substrate immediately before the assay; the remaining material was kept at -80° C and was used up within two days. The reaction was monitored over 10 min at room temperature. IC50 values were calculated from plots of enzyme activity versus the log of the inhibitor concentration using the GRAFIT-IC50-4 parameter fit software (Grafit 4.021, Erithacus).

4.5. Crystallization and data collection

InhA (0.1 mg/ml =3 □M) was mixed at 1:1:2 ratio with NADH and compound b3 respectively (1% DMSO) in a 10 ml volume. The mixture was then concentrated to 0.1 ml and crystallized by hanging drop vapor diffusion. Protein co-crystals were grown in 100mM HEPES pH 7.5, 8% MPD, 50 mM sodium citrate pH 6.5 according to previously published conditions.9,22 Diffraction data were collected, from single crystals, under cryoconditions at Beamline 8.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source (ALS) at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley, CA).

4.6. Structure determination and refinement

Data were indexed and scaled by using ELVES 23 and DENZO/SCALEPACK 24. The molecular replacement solutions were found by using single subunit of InhA derived from the Protein Data Bank file 1P45 7 as a search model. Molecular replacement and subsequent refinement calculations were performed with CNS 25. The models were built by using Quanta (Accelrys). Topology and parameter files for all ligands were obtained from the Hetero-compound Information Centre - Uppsala (Hic-Up).26 The final statistics are listed in Table 3. The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) under the PDB ID codes 2NSD.

Table 3.

Statistics for data collection and refinement

| 5344590 | |

| Crystal data | |

| Space group | I 21 21 21 |

| Cell dimensions, Å | |

| a | 91.263 |

| b | 91.327 |

| c | 184.259 |

| alpha/beta/gamma | 90 |

| Data collection statistics | |

| Wavelength, Å | 1.1159 |

| Number of reflections | 55379 |

| Redundancy (last shell) | 4.3 (3.9) |

| Completeness (last shell), % | 90.9 (77.9) |

| Rsym | 0.05 |

| I/σ (last shell) | 24.2 (0.696) |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution, Å | 1.9 |

| Reflections in working set | 51136 |

| Reflections in test set (7.0%) | 4243 |

| Rcrystal/Rfree, % | 0.236/0.259 |

| RMSD bonds, Å | 0.009 |

| RMSD angels, ° | 1.7 |

| B factors, | |

| Average | 40 |

| NAD | 33.7 |

| Inhibitor | 45.7 |

4.7. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination

Compounds were submitted to the Tuberculosis Antimicrobial Acquisition and Coordinating Facility for in vivo determination of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) against M. tuberculosis strain H37Rv using the Alamar Blue Assay.27 The MIC is defined as the lowest concentration of compound required to give 90% inhibition of bacterial growth.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant PO1 GM56531. We thank Kip Guy for help with the development of the screening assay. The antimycobacterial data was provided by the Tuberculosis Antimicrobial Acquisition and Coordinating Facility through a research and development contract with the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. We thank Bob Reynolds for facilitating these assays.

Abbreviations

- ENR

enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase

- TB

tuberculosis

- MDR-TB

multidrug-resistant tuberculosis

- INH

isonicotinic acid hydrazide

- ETA

ethionamide

- HBTU

2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- DIEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentrations

- OCoA

2-trans-octenoyl-CoA

- CoA

Coenzyme A

Footnotes

Nomenclature: compounds with the prefix a or b are from commercial sources, whereas those with a p are synthetic products constructed with the fragments prefixed with an m.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- (1).Banerjee A, Dubnau E, Quemard A, Balasubramanian V, Um KS, et al. inhA, a gene encoding a target for isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1994;263:227–230. doi: 10.1126/science.8284673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wang F, Langley R, Gulten G, Dover LG, Besra GS, et al. Mechanism of thioamide drug action against tuberculosis and leprosy. J Exp Med. 2007;204:73–78. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Takayama K, Wang C, Besra GS. Pathway to synthesis and processing of mycolic acids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:81–101. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.81-101.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhang Y, Heym B, Allen B, Young D, Cole S. The catalase-peroxidase gene and isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature. 1992;358:591–593. doi: 10.1038/358591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Escalante P, Ramaswamy S, Sanabria H, Soini H, Pan X, et al. Genotypic characterization of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from Peru. Tuber Lung Dis. 1998;79:111–118. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1998.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Morlock GP, Metchock B, Sikes D, Crawford JT, Cooksey RC. ethA, inhA, and katG loci of ethionamide-resistant clinical Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3799–3805. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.12.3799-3805.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Kuo MR, Morbidoni HR, Alland D, Sneddon SF, Gourlie BB, et al. Targeting tuberculosis and malaria through inhibition of Enoyl reductase: compound activity and structural data. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:20851–20859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211968200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sullivan TJ, Truglio JJ, Boyne ME, Novichenok P, Zhang X, et al. High affinity InhA inhibitors with activity against drug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:43–53. doi: 10.1021/cb0500042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).He X, Alian A, Stroud R, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Pyrrolidine carboxamides as a novel class of inhibitors of enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Chem. 2006;49:6308–6323. doi: 10.1021/jm060715y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).McGovern SL, Caselli E, Grigorieff N, Shoichet BK. A common mechanism underlying promiscuous inhibitors from virtual and high-throughput screening. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1712–1722. doi: 10.1021/jm010533y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Ryan AJ, Gray NM, Lowe PN, Chung CW. Effect of detergent on “promiscuous” inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2003;46:3448–3451. doi: 10.1021/jm0340896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ward WH, Holdgate GA, Rowsell S, McLean EG, Pauptit RA, et al. Kinetic and structural characteristics of the inhibition of enoyl (acyl carrier protein) reductase by triclosan. Biochemistry. 1999;38:12514–12525. doi: 10.1021/bi9907779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Qiu X, Janson CA, Court RI, Smyth MG, Payne DJ, et al. Molecular basis for triclosan activity involves a flipping loop in the active site. Protein Sci. 1999;8:2529–2532. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.11.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Roujeinikova A, Levy CW, Rowsell S, Sedelnikova S, Baker PJ, et al. Crystallographic analysis of triclosan bound to enoyl reductase. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:527–535. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Levy CW, Roujeinikova A, Sedelnikova S, Baker PJ, Stuitje AR, et al. Molecular basis of triclosan activity. Nature. 1999;398:383–384. doi: 10.1038/18803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Stewart MJ, Parikh S, Xiao G, Tonge PJ, Kisker C. Structural basis and mechanism of enoyl reductase inhibition by triclosan. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:859–865. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Horton DA, Bourne GT, Smythe ML. The Combinatorial Synthesis of Bicyclic Privileged Structures or Privileged Substructures. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:893–930. doi: 10.1021/cr020033s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Berkheij M, van der Sluis L, Sewing C, Den Boer DJ, Terpstra JW, et al. Synthesis of 2-substituted piperazines via direct α-lithiation. Tetrahedron Letters. 2005;46:2369–2371. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Brik A, Lin YC, Elder J, Wong CH. A quick diversity-oriented amide-forming reaction to optimize P-subsite residues of HIV protease inhibitors. Chem Biol. 2002;9:891–896. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00184-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lee LV, Mitchell ML, Huang SJ, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB, et al. A potent and highly selective inhibitor of human alpha-1,3-fucosyltransferase via click chemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9588–9589. doi: 10.1021/ja0302836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wu CY, Chang CF, Chen JS, Wong CH, Lin CH. Rapid diversity-oriented synthesis in microtiter plates for in situ screening: discovery of potent and selective alpha-fucosidase inhibitors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003;42:4661–4664. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Dessen A, Quemard A, Blanchard JS, Jacobs WR, Jr., Sacchettini JC. Crystal structure and function of the isoniazid target of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1995;267:1638–1641. doi: 10.1126/science.7886450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Holton J, Alber T. Automated protein crystal structure determination using ELVES. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1537–1542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306241101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Databases in protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:1119–1131. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998007100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Collins L, Franzblau SG. Microplate alamar blue assay versus BACTEC 460 system for high-throughput screening of compounds against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1004–1009. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]