Abstract

Background

The pancreas is an occasional site of metastases from melanoma. It may be the only location of metastatic disease, but more often the melanoma metastasises to other organs as well. Treatment options are somewhat limited, and the role of operative treatment is poorly defined.

Case outlines

Two patients presenting with abdominal pain were found to have pancreatic lesions. A 45-year-old woman had a pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy for a mass in the head of pancreas; concurrent liver nodules were treated by segmental liver resection. A 55-year-old man had a total pancreatectomy for multiple pancreatic tumours. Both patients gave a history of ocular melanoma, diagnosed >10 years previously. They had no evidence of malignancy elsewhere. Histology of resected specimens confirmed metastatic melanoma with features consistent with an ocular primary. All resection margins were clear of malignancy, and no lymph node metastases were detected. At 6 months follow-up there were no signs of tumour recurrence.

Discussion

Complete surgical resection offers potential cure in selected patients with metastatic melanoma involving the pancreas, when there is no evidence of widespread disease.

Keywords: ocular melanoma, pancreatic metastases, liver metastases, complete surgical resection

Introduction

Metastases to the pancreas occur from a variety of primary neoplasms. In most cases, metastastic disease is widespread and pancreatic resection offers no potential survival benefit 1,2. However, in certain situations metastases are confined to the pancreas, and this may be the main determinant of long-term survival.

The most common sites of primary malignancy associated with isolated pancreatic metastases are the kidney, lung, breast, colon and skin 3. Potential survival benefits of pancreatic resection in selected patients, especially those with metastases from renal cell carcinoma, are established 4,5. However, experience with pancreatic resection for metastatic melanoma is limited and controversial.

Two patients with pancreatic metastases from ocular melanoma were treated by pancreatic resection. The available literature is reviewed to determine the survival benefits of pancreatic surgery for metastatic melanoma.

Patients

Case No. 1

A 45-year-old woman presented with several months of abdominal discomfort. There was no history of weight loss, change in bowel habit or excessive alcohol intake. Twelve years previously, an ocular melanoma had been diagnosed and treated by transcleral resection. Histology had revealed a 10-mm diameter mixed spindle and epithelioid cell melanoma. Twelve months after therapy, there was local recurrence requiring laser therapy. Laser treatment was required on two further occasions to manage recurrences. The patient had been free of any detectable ocular disease for at least 3 years before her recent presentation and on examination she appeared well. There was no abdominal tenderness, masses, organomegaly or abnormal skin lesions. Ocular examination showed no evidence of recurrent melanoma.

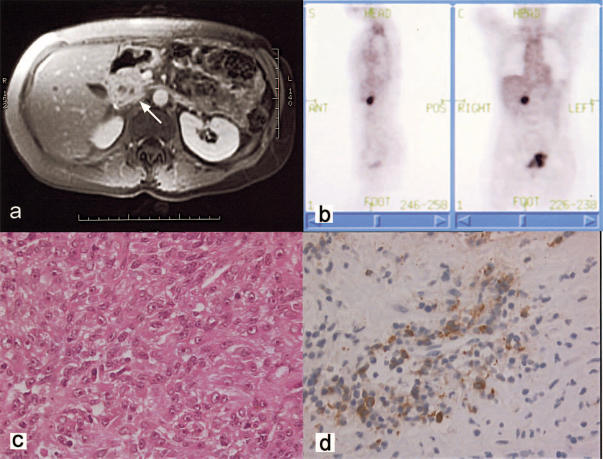

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a non-discrete mass in the head of the pancreas (Figure 1a). Three-to-four well-defined nodules measuring 5–10 mm in diameter were clustered together in the right lobe of the liver. Full blood examination, liver function tests, urea and electrolytes and serum amylase were normal. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (CA 19.9) were not elevated. Fine-needle aspiration of a liver nodule revealed melanoma. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans to assess the extent of disease showed high uptake only in the region of the pancreatic head (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. .

(a) MRI scan showing a mass in the head of the pancreas (arrow). PET scan showing focal uptake in the region of the pancreatic head. (b) H&E section of the melanoma demonstrating mixed spindle and epithelioid cell types with minimal melanin production within fibrous connective tissue (×800). (c) Immunoperoxidase study showing strong immunoreactivity of cells with Melon A (×800).

At laparotomy, a non-pigmented mass measuring approximately 30 mm in maximum diameter was noted on the superior aspect of the pancreas, involving the distal common bile duct. Frozen section confirmed melanoma. Three tumours measuring 5–10 mm diameter were identified in segment 5 of the liver by intra-operative ultrasound. A pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy and segmental liver resection were performed to resect all macroscopic disease. Histopathology of the resected specimens revealed a mixed spindle cell and epithelial cell melanoma, with positive staining for S-100 and Melan A (Figure 1c and d). All resection margins were clear of tumour and there was no lymph node involvement. The excised metastases had the same morphological features as the previously treated ocular melanoma. The patient made a complete recovery and was without evidence of disease 6 months postoperatively.

Case No. 2

A 55-year-old-man presented with 2 weeks of mild epigastric pain, without associated weight loss or change in bowel habit. He was a non-smoker, with a 25-year history of moderate alcohol intake (30 g/day). Enucleation of one eye for an ocular melanoma had been performed 13 years previously, identifying a 12-mm diameter spindle cell melanoma extending to the optic nerve. Physical examination revealed no abdominal masses, lymphadenopathy or skin lesions.

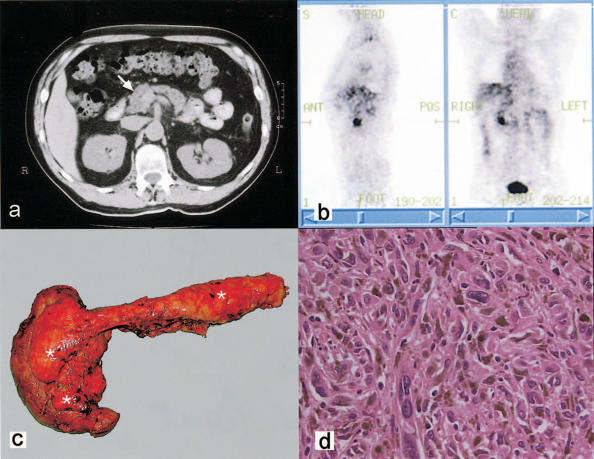

CT of the abdomen showed an ill-defined mass in the head of the pancreas (Figure 2a). The possibility of a malignant tumour arising from the duodenum could not be excluded, and an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed. Complete visualisation of the duodenum showed no evidence of malignancy. Further investigations to identify the nature of the mass included percutaneous fine-needle aspiration, which was inconclusive. All blood tests including CEA and CA 19.9 were normal. A CT scan of the thorax and brain, as well as whole-body PET scan were performed to exclude the possibility of disease elsewhere. PET scan showed increased uptake only in the region of the pancreatic head (Figure 2b). CT scans of the thorax and brain were normal.

Figure 2. .

(a) CT scan of the abdomen identifying an ill-defined mass in the pancreatic head (arrow). (b) PET scan demonstrating significant uptake in the region of the pancreatic head. (c) Resected pancreas and duodenum with multiple foci of highly pigmented melanoma (*) with the greatest number in the uncinate process. (d) H&E section of melanoma cells with a spindle cell appearance with melanin pigment production (×800).

At operation multiple pigmented lesions were noted in the pancreatic head, predominantly in the uncinate process (Figure 2c). Isolated lesions measuring approximately 5 mm in diameter were also identified in the pancreatic body and tail. There was no suggestion of malignant disease elsewhere in the abdomen. A total pancreatectomy was performed, with histology revealing metastatic spindle cell melanoma confined to the pancreas, without lymph node involvement (Figure 2d). The patient made an uncomplicated recovery. There was no evidence of recurrence 7 months post-operatively.

Discussion

The pancreas is frequently involved in metastatic disease. The incidence ranges from 3% to 10% in reported autopsy series 1,2. In most cases, pancreatic involvement is an incidental finding in a patient with widespread metastatic disease. Isolated metastases to the pancreas are rare. However, in patients with a previous history of malignancy, an identified pancreatic mass is due to a secondary deposit in about 40% of cases 6. In all, approximately 1% of pancreatic resections are performed for metastases 5.

The pancreas is a favoured site for isolated metastases from renal cell carcinoma 4,7. Pancreatic resection for these patients may improve survival and may be curative 4,7. However, the benefits of pancreatic surgery in patients with melanoma and other primary malignancy are less certain. Pancreatic involvement with melanoma occurs in approximately 50% of cases in which there is disseminated disease 8. Isolated pancreatic metastases from melanoma are rare. They occur in no more than 2% of patients with visceral metastases and originate disproportionately from primary ocular melanoma 9,10,11.

It is generally accepted that specific clinical and pathological factors influence survival in patients with primary melanoma. These include tumour depth, ulceration, histological subtype, anatomical site and lymph node involvement 12. However, the prognostic factors that determine survival for patients with metastases to the pancreas are undetermined. The only factor that appears to be associated with improved survival is a long disease-free interval after the treatment of primary malignancy 4,5,8,13. This phenomenon is thought to reflect favourable tumour biology with a slow growth pattern and the relative rarity of lymph node involvement 5.

The survival outcome of patients with visceral metastases from melanoma is dismal regardless of histopatholgical features, with a median survival of 6–12 months 14,15,16. The results of chemotherapy are generally disappointing, despite the development of newer and more effective combination therapies. The overall response rates to chemotherapy vary between 15% and 28%, and long-term remissions are reported in <2% of treated cases 17,18. Presently, surgical resection appears to be the only potentially curative treatment option. The exact role of operation in patients with melanoma metastases is still undefined, however, particularly when more than one organ is involved or in situations in which complete tumour resection is not possible.

The survival outcomes of patients undergoing complete surgical resection for isolated pancreatic melanoma metastases are generally better than those managed by non-surgical modalities 4,5,10,14,16,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. In a series reported by Wood and colleagues 16, six patients with isolated metastases to the pancreas were treated by complete surgical resection. The median survival in this group was 24 months, and the 5-year survival was 50%. In all, 30 patients in this series had complete resection of isolated melanoma metastases to the liver, adrenal, pancreas or spleen, with a 5-year survival of 23%. In the same series, the 5-year survival of 778 patients with non-operative management of visceral melanoma metastases was only 9%. Several other melanoma series support the finding of improved survival in patients with complete resection of isolated pancreatic metastases 15,24.

The value of operative treatment in patients with melanoma and multiple metastases involving a single organ or more than one visceral site is far less convincing. There are a few reports of long-term survival after resection of multiple metastases from melanoma 15,16,26,27,28. Salmon and associates 29 reported on surgical resection for melanoma combined with chemotherapy in 18 patients with multiple liver metastases (mostly bilobar) and one patient with an isolated liver secondary. The overall median survival was 22 months, which was significantly better than that quoted for historical controls. In a series of 14 patients with melanoma involving more than one abdominal viscus, the median survival was 27.5 months and 5-year survival was 25% 16. However, there are no specific reports of survival outcomes for patients with metastatic melanoma treated by combined pancreatic and liver resection; combined bowel and solid organ resection is far more common 15.

Surgical resection is considered incomplete if resection margins contain malignancy or when not all metastases are treated surgically. Wood's series 16 included two patients with metastatic melanoma to the pancreas that had incomplete resection, with a median survival of 8 months; this figure was no better than the survival of untreated patients. The situation was similar in those with incomplete resection of liver or adrenal metastases. Incomplete surgical resection appears to have no survival benefit.

Some authorities consider the ability to achieve complete tumour clearance as more important than the number of detectable metastatic lesions 16,29. This policy makes the identification of all distal disease extremely important. In patients with metastatic melanoma being considered for surgical intervention, PET scanning appears to be a particularly useful assessment tool 30. PET has a higher sensitivity and specificity than conventional imaging for detecting metastatic melanoma in all regions of body except the thorax 30,31. In a study by Rinne and co-workers 31, PET was able to detect abdominal metastases in all known cases (25 of 25), compared with a 32% sensitivity (8 of 25) with conventional imaging. However, the sensitivity of PET is lower for tumours <1 cm, because of limitations of scanner resolution. In addition, detailed anatomical localisation of metastatic disease usually requires conventional imaging. Therefore, PET and conventional scanning should be considered complementary imaging modalities.

Currently there is no satisfactory non-surgical treatment for metastatic melanoma. Surgical resection of metastases to the pancreas after thorough assessment for occult distal disease can provide long-term survival. However, all metastatic disease needs to be excised if operation is to offer any survival benefit.

References

- 1.Willis RA. Butterworth; London: 1973. The Spread of Tumors in the Human Body3rd edn; pp. 216–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cubilla AL, Fitzgerald PJ. Moosa AR. Willimans & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1980. Surgical pathology of tumors of the exocrine pancreas, Tumors of the Pancreas; pp. 159–63. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Z'Graggen K, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Sigala H, Warshaw AL. Metastases to the pancreas and their surgical extirpation. Arch Surg 1998;133:413–17; discussion 418–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hiotis SP, Klimstra DS, Conlon KC, Brennan MF. Results after pancreatic resection for metastatic lesions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:675–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02574484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrison LE, Merchant N, Cohen AM, Brennan MF. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for nonperiampullary primary tumors. Am J Surg. 1997;174:393–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roland CF, van Heerden JA. Nonpancreatic primary tumors with metastasis to the pancreas. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;168:345–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirota T, Tomida T, Iwasa M, Takahashi K, Kaneda M, Tamaki H. Solitary pancreatic metastasis occurring eight years after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. A case report and surgical review. Int J Pancreatol. 1996;19:145–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02805229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das Gupta TK, Brasfield RD. Metastatic melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Surg. 1964;88:969–73. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1964.01310240065013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Assessment of metastatic disease status at death in 435 patients with large choroidal melanoma in the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS): COMS report no. 15. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:670–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodish RJ, McFadden DW. The pancreas as the solitary site of metastasis from melanoma. Pancreas. 1993;8:276–8. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199303000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel JK, Didolkar MS, Pickren JW, Moore RH. Metastatic pattern of malignant melanoma. A study of 216 autopsy cases. Am J Surg. 1978;135:807–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(78)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed I. Malignant melanoma: prognostic indicators. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72:356–61. doi: 10.4065/72.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le Borgne J, Partensky C, Glemain P, Dupas B, de Kerviller B. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for metastatic ampullary and pancreatic tumors. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:540–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharpless SM, Das Gupta TK. Surgery for metastatic melanoma. Semin Surg Oncol. 1998;14:311–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199806)14:4<311::aid-ssu7>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overett TK, Shiu MH. Surgical treatment of distant metastatic melanoma. Indications and results. Cancer. 1985;56:1222–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850901)56:5<1222::aid-cncr2820560544>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wood TF, DiFronzo LA, Rose DM, et al. Does complete resection of melanoma metastatic to solid intra-abdominal organs improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:658–62. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0658-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crosby T, Fish R, Coles B, Mason MD. Systemic treatments for metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev2000:CD001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woll E, Bedikian A, Legha SS. Uveal melanoma: natural history and treatment options for metastatic disease. Melanoma Res. 1999;9:575–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.England MD, Sarr MG. Metastatic melanoma: an unusual cause of obstructive jaundice. Surgery. 1990;107:595–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rutter JE, De Graaf PW, Kooyman CD, Van Leeuwen MS, Obertop H. Malignant melanoma of the pancreas: primary tumour or unknown primary? Eur J Surg. 1994;160:19–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pingpank JF, Jr, Hoffman JP, Sigurdson ER, Ross E, Sasson AR, Eisenberg BL. Pancreatic resection for locally advanced primary and metastatic nonpancreatic neoplasms. Am Surg 2002;68:337–40; discussion 340–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham JD, Cirincione E, Ryan A, Canin-Endres J, Brower S. Indications for surgical resection of metastatic ocular melanoma. A case report and review of the literature. Int J Pancreatol. 1998;24:49–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02787531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bianca A, Carboni N, Di Carlo V, et al. Pancreatic malignant melanoma with occult primary lesion. A case report. Pathologica. 1992;84:531–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong JH, Skinner KA, Kim KA, Foshag LJ, Morton DL. The role of surgery in the treatment of nonregionally recurrent melanoma. Surgery. 1993;113:389–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Histopathologic characteristics of uveal melanomas in eyes enucleated from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study. COMS report no. 6. Am J Ophthalmol 1998;125:745–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer T, Merkel S, Goehl J, Hohenberger W. Surgical therapy for distant metastases of malignant melanoma. Cancer. 2000;89:1983–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001101)89:9<1983::aid-cncr15>3.3.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fletcher WS, Pommier RF, Lum S, Wilmarth TJ. Surgical treatment of metastatic melanoma. Am J Surg. 1998;175:413–17. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agrawal S, Yao TJ, Coit DG. Surgery for melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:336–44. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0336-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salmon RJ, Levy C, Plancher C, et al. Treatment of liver metastases from uveal melanoma by combined surgery-chemotherapy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1998;24:127–30. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(98)91485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prichard RS, Hill AD, Skehan SJ, O'Higgins NJ. Positron emission tomography for staging and management of malignant melanoma. Br J Surg. 2002;89:389–96. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2002.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rinne D, Baum RP, Hor G, Kaufmann R. Primary staging and follow-up of high risk melanoma patients with whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography: results of a prospective study of 100 patients. Cancer. 1998;82:1664–71. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980501)82:9<1664::aid-cncr11>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]