Abstract

Background

Even though laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has become the customary method for treating gallstones, some incidents and complications appear rather more frequently than with the open technique. Several aspects of these complications and their treatment possibilities are analysed.

Materials and methods

Over the last 9 years 9542 LCs have been performed at this centre, of which 13.9% were carried out for acute cholecystitis, 38.4% in obese patients and 7.6% in patients aged >65 years.

Results

The main operative incidents encountered were haemorrhage (224 cases, 2.3%), iatrogenic perforation of the gallbladder (1517 cases, 15.9%) and common bile duct (CBD) injuries (17 cases, 0.1%). Conversion to open operation was necessary in 184 patients (1.9%), usually due to obscure anatomy as a result of acute inflammation. The main postoperative complications were bile leakage (54 cases), haemorrhage (15 cases), sub-hepatic abscess (10 cases) and retained bile duct stones (11 cases). Ten deaths were recorded (0.1%).

Discussion

Most of the postoperative incidents (except bile duct injuries) were solved by laparoscopic means. Among patients with postoperative complications 28.9% required revisional surgery. In 42.2% of cases minimally invasive procedures were used successfully: 15 laparoscopic re-operations (for choleperitoneum, haemoperitoneum and subhepatic abscess) and 22 endoscopic sphincterotomies (for bile leakage from the subhepatic drain and for retained CBD stones soon after operation). The good results obtained allow us to recommend these minimally invasive procedures in appropriate patients.

Keywords: laparoscopic cholecystectomy, incidents, complications, minimally invasive treatment of complications

Introduction

During the past decade laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has become the procedure of choice in the surgical treatment of symptomatic biliary lithiasis. The operation is not completely risk-free, some incidents and complications being more frequent than with open cholecystectomy (OC). This study analysed the frequency of these complications and the best methods of treating them.

Materials and methods

Between December 1992 and September 2001, 14024 biliary operations were performed in Surgical Clinic no. 3 at Cluj-Napoca, of which 4482 (32%) were open procedures. Gallstones were present in the main bile duct in 719 of these cases.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) was performed in 9542 (68%) of these patients, 1659 (17.4%) being men and 7883 (82.6%) women. Ages ranged between 14 and 91 years, and 732 patients were aged over 65 years. The operative diagnoses are given in Table 1. The series included two pregnant women in the second trimester of pregnancy and 3672 obese patients (Table 2).

Table 1. Operative diagnoses.

| Diagnosis | Number of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Acalculous cholecystitis | 677 (7.09) |

| Chronic calculous cholecystitis | 6782 (71.07) |

| Gallbladder mucocele | 371 (3.88) |

| Acute cholecystitiss | 1334 (13.98) |

| Sclero-atrophic cholecystitis | 285 (2.98) |

| Gallbladder + CBD lithiasis | 91 (0.95) |

| Gallstones in a gallbladder remnant | 2 (0.02) |

| Total | 9542 (100) |

Table 2. Degrees of obesity (using the Metropolitan Insurance Company formula).

| Degree | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| 1st degree (20–24% over ideal weight) | 989 (26.93) |

| 2nd degree (25–30% over ideal weight) | 963 (26.22) |

| 3rd degree (31–99% over ideal weight) | 1682 (45.80) |

| 4th degree (morbid obesity) | 38 (1.03) |

| Total | 3672 |

The procedure used for LC was that recommended by Zucker 1 regarding both placement of the operative team and the sites of trocar insertion. For intra-operative exploration of the main bile duct selective laparoscopic cholangiography was performed when dilatation of the cystic duct (>3 mm diameter) was associated with small calculi in the gallbladder. We also performed choledochoscopy by the transcystic route in 153 cases and by choledochotomy in 4 cases, with extraction of calculi from the main bile duct in 91 cases. Laparoscopic ultrasound (US) was rarely performed (with demonstration equipment provided by manufacturing companies). It is more sensitive and simple to perform because it does not necessitate dissection of the cystic duct in the presence of acute inflammation. If stone migration was suspected and the main bile duct could not be explored, ERCP was performed 3–5 days postoperatively.

Results

Technical difficulty

The degree of difficulty of the operation was assessed by Cuschieri's scale 2 (Table 3). Acute cholecystitis, a shrunken fibrotic gallbladder and the presence of cirrhosis created particular difficulty, sometimes requiring conversion to open operation. Great difficulty (grades III and IV) was correlated with the male sex, age >65 years and the presence of an inflammatory syndrome. The patients with grade III and IV difficulty accounted for 78.9% of those with high fever in association with biliary colic and for 82.4% of the patients in whom US revealed a thickened gallbladder wall. This thickness was caused either by inflammation of the gallbladder wall or by the adherence of the greater omentum to the gallbladder.

Table 3. Degree of difficulty at operation.

| Grade | Number of cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Grade 1 | 5940 (62.2) |

| Grade II | 2656 (27.8) |

| Grade III | 762 (7.9) |

| Grade IV | 184 (1.9) |

Cuschieri's classification was used 2.

Intra Operative accidents and incidents

The following problems were examined: haemorrhage, injury of the bile ducts and conversion to open operation.

Haemorrhage (Table 4) was caused by tangential side lesions of the cystic artery (78 cases) and, more rarely, by its total sectioning (16 cases). In 94 cases laparoscopic haemostasis was achieved by clipping the artery between the lesion and its origin. Only one case required conversion to an open operation. Bleeding from the gallbladder bed (110 cases) was noted especially in those patients with acute cholecystitis or cirrhosis. In 105 of these patients haemostasis was achieved by using a Tacho-Comb patch (Nycomed), while in 5 cases conversion was needed with haemostasis by suturing the peritoneum of the gallbladder.

Table 4. Intra-operative haemorrhage: 224 cases (2.3%).

| 1. From cystic artery | 95 | Tangential lesions | 78 |

| Total section | 16 | ||

| Conversions | 1 | ||

| 2. From gallbladder bed | 110 | Treatment with Tacho-Comb | 105 |

| Conversions | 5 | ||

| 3. From hepatic artery | 1 | Conversions | 1 |

| 4. From greater omentum | 18 | Laparoscopic haemostasis | 16 |

| Conversions | 2 |

Injury of the bile ducts (Table 5) occurred in 17 (0.1%) patients, 14 of the injuries being identified intra-operatively. According to Way's classification (cited in ref. 3), three were grade I (tangential), 13 grade IIIA (total sectioning without loss of substance) and one grade IV (total sectioning of CBD with loss of substance). In four patients insertion of a T-tube drain was sufficient, and in one case laparoscopic bile duct suture was performed. In the other 12 patients bile flow was reestablished by Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy.

Table 5. Bile duct injuries (17 cases, 0.1%).

| Right hepatic duct lesions | |

| Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy | 3 |

| T-tube drainage | 2 |

| CBD lesions | |

| Total section (Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy) | 9 |

| Partial lesions (T-tube drainage) | 2 |

| Tangential lesions (laparoscopic choledochorrhaphy) | 1 |

Except for three injuries (two of the right hepatic duct and one of the CBD), all the others were discovered intra-operatively. No lesions of the main bile duct were found on cholangiography, because we did not perform control cholangiography at the end of the operation. All lesions were therefore discovered during the dissection.

In 9 of the 17 cases of injury, the anatomy was obscured by acute cholecystitis, and the others occurred in patients with a shrunken fibrosed gallbladder (apart from one obese patient).

Perforation of the gallbladder during dissection or extraction was recorded in 1517 (15.9%) patients. The incident is more troublesome than serious, especially when grasping and extraction of lost gallstones in the peritoneal cavity is necessary; this manoeuvre prolongs the operation.

Conversion to open operation was necessary in 184 (1.9%) cases (Table 6). Acute cholecystitis with pericholecystitis was recorded in 124 patients and was the predominant reason for conversion. Peritoneal adhesions in the scarred abdomen were a conversion cause in only 6 of 179 patients. To avoid adhesions, a right upper quadrant approach was used in 98 patients, Hasson trocar in 54 patients, Visiport device in 12 patients and optical Veress needle in 9 patients. Thus LC was performed in 41 patients with previous gastrectomy and in 3 patients with a history of liver hydatid cyst.

Table 6. Conversion to open operation (184 cases, 1.9%).

| Obligatory conversions | Total section of the CBD | 9 |

| Partial lesions of the CBD | 2 | |

| Lesion of the right hepatic duct | 2 | |

| Bile leakage from the gallbladder bed | 2 | |

| Haemorrhage from the gallbladder bed | 5 | |

| Haemorrhage from the omental vessels | 2 | |

| Haemorrhage from the cystic artery | 1 | |

| Haemorrhage from right hepatic artery | 1 | |

| Elective conversions | Pericholecystitis | 124 |

| Internal biliary fistula | 13 | |

| Adhesions after previous laparotomy | 6 | |

| CBD stones | 7 | |

| Technical reasons (rupture of the Dormia probe, etc.) | 5 | |

| Perforated gallbladder | 2 | |

| Gallbladder neoplasms | 3 |

Early postoperative complications (Table 7)

Table 7. Early complications and their treatment.

| Complication | Conservative treatment | Minimally invasive treatment | Open surgery | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bile leak | 19 | 11 EST | 4 | 34 |

| Choleperitoneum | – | 5 laparoscopic | 15 | 20 |

| Postoperative haemorrhage | 7 | 4 laparoscopic | 4 | 15 |

| Subhepatic abscess | – | 7 laparoscopic | 3 | 10 |

| Retained bile duct stone | – | 11 EST | – | 11 |

| Total | 26 (28.9%) | 38 (42.2%) | 26 (28.8%) | 90 |

EST, endoscopic sphincterotomy.

Complications directly related to the surgical technique were graded according to Clavien's classification 4.

Grade I complications, which affect the ideal postoperative course but do not require treatment, include suppuration at the umbilical trocar site, which occurred on days 5–7. There were 137 (1.4%) such cases of limited extent, cured by local treatment within a few days; 108 of these occurred in patients operated for acute cholecystitis, and obesity was present in 28 of them.

Grade IIA complications require conservative treatment and prolong hospitalisation but leave no sequelae. There were 19 patients with a bile leak and 7 with haemorrhage via the subhepatic drain. Drainage was quantitatively moderate in amount (approx. 50–60 ml blood and 250–300 ml bile per day), persisted for 6–10 days and stopped spontaneously. In 11 patients with bile leak, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) was performed, sometimes associated with a transpapillary stent, followed by a diminished biliary drainage, which finally stopped. Fifteen of these patients were operated for acute cholecystitis and 8 were obese.

Grade IIB complications require laparotomy or laparoscopic re-intervention or endoscopic manoeuvres, but heal without sequelae. In four patients with a massive bile leak (600–800 ml/day) in the subhepatic drain, revisional operation was performed. Suture of the gallbladder peritoneum was required in one patient. T-tube drainage was required in two patients with tangential lesions of the right hepatic duct and a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy in one patient with total section of the CBD. These three CBD lesions were missed at the original operation.

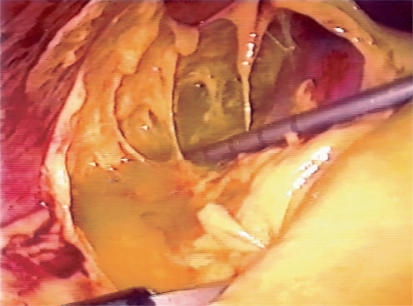

Choleperitoneum occurred in patients operated for acute cholecystitis without insertion of a subhepatic drain. Fifteen such patients required formal laparotomy, with suture of the gallbladder peritoneum and drainage. In another five patients a laparoscopic re-intervention was performed (Figure 1), and in two cases there were aberrant bile ducts in the gallbladder bed, which were clipped. Among all these patients with choleperitoneum, there were 14 with acute cholecystitis.

Figure 1. .

Infected choleperitoneum. A laparoscopic re-intervention was performed 18 days after LC.

Prolonged bleeding from the gallbladder bed necessitated suture of the gallbladder peritoneum in three patients. In four patients haemostasis was achieved by laparoscopic re-intervention and by application of a Tacho-Comb patch in the gallbladder bed.

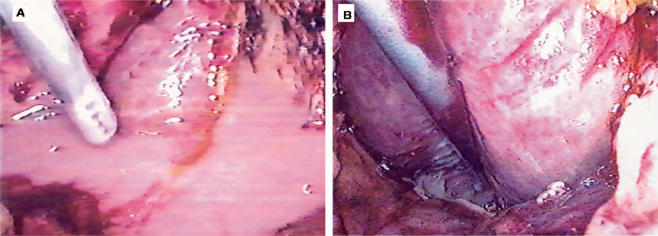

Subhepatic abscess occurred in 10 patients with a difficult cholecystectomy (7 for acute cholecystitis). Three of those were re-operated, and seven had laparoscopic drainage (Figure 2).

Figure 2. .

Subhepatic abscess. (A) Suctioning the contents of the abscess. (B) The abscess cavity (arrow) was evacuated and a tube drain was placed.

Grade III complications were not recorded, i.e. complications (other than bile duct stricture) developing after surgical or laparoscopic re-operation.

Grade IV represents death and there were 10 such cases (0.1%). Two patients with bile leakage required revisional operation and developed irreversible septic shock. The third patient, with myasthenia gravis, became decompensated at 5 days and died of respiratory failure. Another two women died suddenly from myocardial infarct. A cirrhotic patient developed disseminated intra-vascular coagulation 12 h after the operation, and another developed acute liver failure. Two patients died from pulmonary embolism and one from stroke. Altogether three of these patients were obese (grade II and IV) and developed septic shock and liver failure.

Late postoperative complications

At late postoperative follow-up (3 months and 1 year) we found residual calculi in 14 patients. These patients had no intra-operative exploration of the bile duct and had no preoperative clinical or laboratory evidence of ductal stones. Their calculi were extracted using endoscopic sphincterotomy. One of these patients died from necrotising acute pancreatitis, following the sphincterotomy.

Umbilical site incisional hernia occurred in 12 patients who required either an extended incision for extraction of large calculi or who developed local infection at the umbilicus. All hernias were repaired.

Discussion

The risks and complications of LC must be neither over-rated nor under-rated. Laparoscopy is not easy for the surgeon, thorough instruction as well as experience being crucial for improvement of results. Contrary to initial reports of an increased complication rate, recent data show that LC entails lower morbidity and mortality rates than open operation 5,6,7,8. In the comparative study by Jatzko et al.9, open operation was associated with a 7.7% morbidity rate, compared with 1.9% for LC, and a 5% mortality rate vs 1% for LC.

One of the most frequent situations carrying an increased operative risk is acute cholecystitis. First, pericholecystitis modifies the local anatomy and increases the difficulty of identifying the cystic pedicle and CBD. Because it is impossible to perform antegrade cholecystectomy in most such cases, there is a high risk of CBD injury. Second, the cleavage plane in the gallbladder bed is lost, and that makes it easy to penetrate the liver parenchyma during dissection of the gallbladder, thus creating the possibility of postoperative bile leak, haemorrhage and subhepatic abscess. Other situations associated with increased difficulty in cholecystectomy are a shrunken fibrotic gallbladder, cirrhosis (when a regenerating nodule extends into the gallbladder bed) and, in a few cases, obesity if there is marked fatty infiltration of the cystic pedicle. However, the postoperative morbidity and mortality rates, as well as the excellent late results, allow us to conclude that obese patients are the principal beneficiaries of the laparoscopic technique. It avoids the wound infection, wound dehiscence and especially the incisional hernia that often complicate open cholecystectomy in the obese.

The major problems related to LC are bile duct injury, haemorrhage and subhepatic abscess. Lesions of the extrahepatic bile ducts can occur at any level as follows. Detachment of the gallbladder may open any accessory bile ducts present in the gallbladder bed 10,11,12,13; post-mortem studies demonstrate their presence in 3–5% of individuals 11. However, accessory bile ducts were only recognised in three patients immediately after detachment of the gallbladder. Postoperative bile leak and choleperitoneum were avoided by clipping these ducts. When bile leakage >500 ml/24 h persists in the early postoperative period, endoscopic sphincterotomy or transpapillary stenting are recommended 14,15,16,17. Bile duct decompression usually leads to cessation of the bile leak, thus avoiding re-operation. Choleperitoneum may develop in patients without a subhepatic drain. In well equipped hospitals, subhepatic collections can be managed by percutaneous drainage using ultrasound guidance, and this will usually suffice for a leak from the gallbladder bed. We have not had the technical facility to perform percutaneous drainage by ultrasound guidance, but we have evacuated (and drained) five bile collections by laparoscopic re-interventions. In two cases accessory bile ducts were noted in the gallbladder bed and were clipped. In many of these cases detachment at the first operation had been difficult (because the plane was obliterated) and frequently the liver capsule had been reached.

After open cholecystectomy postoperative bile leak or choleperitoneum from cystic duct is rare, but these complications are more frequent in LC. Woods et al.12 noted this cause in 17 of 34 cases with biliary complications. In our series we noted it in only two patients: one with slippage of the clips from a short cystic stump and another with choleperitoneum at 14 days following necrosis of the cystic duct stump due to transmission of the diathermy current.

The most serious problem is an injury to the main bile duct. Although the differences are not statistically significant, this injury is more frequently seen in LC (1% of cases) 2,3,9,12,18,19 than in open cholecystectomy (0.5% of cases) 5. Analysing 15 cases (0.8%) of CBD injury among 6067 cases operated by laparoscopy in Holland, Schol et al.3 found two common causes. The first cause was acute cholecystitis, which caused difficulty in identifying the anatomy in two-thirds of cases. The duct was injured after a mean dissection of 110 minutes, usually following confusion between the CBD and the cystic duct. Likewise in our series, these lesions occurred in cases with obscured anatomy. Because fundus-first cholecystectomy cannot always be performed, the decision for conversion is justified in any patient in whom the anatomy is unclear. The second cause is the surgeon's lack of experience, a fact proved by the learning curve. Huang et al.8 analysed 6 lesions of the CBD produced in a series of 350 LCs and reported that they occurred among the first 10–15 laparoscopic operations performed by the surgeon.

A particular mode of CBD injury that is specific to LC is clipping the ‘cone’ of CBD with the first clip applied to the cystic duct. To avoid this situation it is preferable to apply the clip at a little distance from the cysticocholedochal junction, because endoscopic studies show that a long cystic stump (without stones) is not a true cause of post-cholecystectomy pain 20.

Congenital biliary anomalies must not be ignored. Two variants are usually encountered. Nine of our patients had an accessory right hepatic duct, which ran into the cystic duct above its junction with the common hepatic duct. The ideal solution is to cut the cystic duct above its confluence with the accessory duct. Another anomaly identifiable only by laparoscopic cholangiography or a good ERCP is entry of the cystic duct into the right hepatic duct. We have encountered this anomaly in five patients, three of whom suffered a complete section of the right hepatic duct.

As regards haemorrhage, even though arterial injury is usually a reason for conversion 6,7, in our series haemostasis was achieved almost exclusively by laparoscopic means. Generally, the uncontrolled reaction of the surgeon is more dangerous than the haemorrhage itself: blind clip application or, even more serious, the blind use of the electrocautery hook can cause severe injury to the bile duct. Rapid grasping of the injured vessel will usually allow good temporary laparoscopic haemostasis and then, by clipping, definitive control. Only in one patient in whom the cystic artery was too short (or sectioned near its origin) was laparotomy needed for haemostasis.

Haemorrhage from the gallbladder bed was encountered more frequently in acute cholecystitis, in patients with a shrunken fibrotic gallbladder and in cirrhotics. Haemostasis was achieved by using a Tacho-Comb patch (Nycomed) or even by conversion in order to suture the peritoneum of the gallbladder (four cases). Argon beam coagulation was not available.

Bile leakage and bleeding may determine subhepatic abscess formation. Huang et al.8 reported 3 such complications in a group of 350 LCs. The clinical picture was manifest 7–10 days after operations performed for acute cholecystitis. Pain in the right upper quadrant, fever, leucocytosis and ultrasonography led to the diagnosis. Evacuation and drainage of the abscess were performed by open operation in three cases and by laparoscopic means in the other seven. An excellent opportunity for minimally invasive treatment is offered by US-guided percutaneous drainage, if the means are available to perform it in safe conditions.

In an earlier study 21, comparing laparoscopic with open cholecystectomy, we found that bile leak and haemorrhage from the gallbladder bed were 2.7 times less frequent in OC and no subhepatic abscess was encountered. In open cholecystectomy we practised routine suture of the gallbladder peritoneum 22. The same manoeuvre solved the incidents or complications after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 19 patients in whom re-intervention was needed. We therefore believe that inability to suture the gallbladder peritoneum represents the ‘Achilles’ heel’ of laparoscopic cholecystectomy 21.

Retained bile bile duct stones were detected at an early stage (1–4 days) in 11 patients. Bile duct stones were suspected at the time of LC because of numerous microcalculi in the gallbladder or a large cystic duct and dilated CBD. Because full investigation of the CBD was impossible at operation (local inflammation or hypertrophic Heister valves making catheterisation impossible) , ERCP with sphincterotomy and calculus extraction was performed 5–6 days after LC.

Of the 90 patients (0.9%) with postoperative complications, open operation was used in 26 cases and laparoscopic re-operations or endoscopic manoeuvres in the remaining 38 (42.2%). Minimally invasive treatment was very efficient and offered optimum healing conditions if correctly indicated, thereby transforming an operative failure into a postoperative success.

References

- 1.Zucker KA. Quality Publishing Inc; St Louis: 1991. Surgical Laparoscopy; pp. 143–82. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuschieri A, Berci G. Laparoscopic Biliary Surgery.Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1992;96–116, 134–2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schol EPG, Go PM, Gouma DJ. Risk factors for bile duct injury in laparoscopic cholecystectomy; analysis of 49 cases. BrJ Surg. 1994;81:1786–8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800811225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clavien PA, Sanabria JR, Strasberg SM. Proposed classification of complications of surgery with examples of utility in cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1992;111:518–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deziel DJ, Milikan KW, Economou SG, et al. Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a national survey of 4292 hospitals and an analysis of 77604 cases. Am J Surg. 1993;165:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80397-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey RW, Zucker KA, Flowers JL, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Arm Surg. 1991;214:531–41. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199110000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Febre JM, Fagot H, Domergne J, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in complicated cholelithiasis. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:1198–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00591050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SM, Wu CW, Mong HT, et al. Bile duct injury and bile leakage in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1590–2. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800801232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jatzko G, Lisborg PH, Perti AM, et al. Multivariate comparison of complications after laparoscopic cholecystomy and open cholecystectomy. Arm Surg. 1995;221:381–6. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199504000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe BM, Gardiner BN, Leary BF, et al. Endoscopic cholecystectomy. Arch Surg. 1991;126:1129–97. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1991.01410340030005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klotz HP, Schlump F, Largiader F. Injury to an accessory bile duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992;2:317–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woods MS, Shellito JL, Santoscoy GS, et al. Cystic duct leaks in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg. 1994;168:560–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(05)80122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edelman DS. Bile leak from the liver bed following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:205–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00591831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bedogni G, Mortilla MG, Ricci E, et al. Meinero M. Ed Masson; Milan: 1994. The role of endoscopic treatment of early biliary complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Laparoscopic Surgery; pp. 145–88. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brandabur JJ, Kozarek RA. Endoscopic repair of bile leaks after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI. 1993;14:375–80. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(05)80057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davids PHP, Rauws EAJ, Tytcat GNJ. Postoperative bile leakage: endoscopic management. Gut. 1992;33:1118–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozarek RA. Endoscopic treatment of biliary injuries. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993;3:261–70. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neugebauer E, Sauerland S, Troidl S. Springer; Paris: 2000. Recommendations for evidence-based endoscopic surgery; pp. 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russel JC, Walsh SJ, Mattie AS, et al. Bile duct injuries,1989–1993. A statewide experience. Connecticut Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Registry. Arch Surg. 1996;131:382–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1996.01430160040007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Äänimaa M, Mäkelä P. The cystic duct stump and the postcholecystectomy syndrome. Arm Chir Gynaecol. 1981;70:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duca S. Publishing House Paralela 45; Piteş ti: 2001. Chirurgia Laparoscopică2nd edn; pp. 189–208. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ham JM.Cholecystectomy, Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract. In:, vol. I. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1988;559–67. [Google Scholar]