Abstract

Background

Metastasis to the pancreas from renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is distinctly uncommon. Most cases are detected at an advanced stage of the disease and are thus unsuitable for resection. A solitary RCC metastasis to the head of pancreas is rarely encountered and, although it is potentially amenable to surgical resection, surgeons may be hesitant to perform pancreatoduodenectomy.

Cases outlines

Two patients with a solitary RCC metastasis to the head of pancreas were treated by pancreatoduodenectomy, while a third with multiple RCC metastases declined any treatment. Two of the patients were asymptomatic, and one presented with anaemia and mild abdominal pain. Computed tomography (CT) and angiography were used to exclude other metastases and to assess resectability of the pancreatic tumour. All three patients are still alive, those with resectable disease at 2 years and 9 years and the one with irresectable disease at 4 years.

Discussion

Isolated RCC metastasis to the pancreas is a rare event. Patients present either on follow-up imaging or with symptoms such as mild abdominal pain, weight loss, jaundice, anaemia or gastrointestinal bleeding (whether occult or overt). Dynamic spiral CT can visualise the tumour and exclude distant metastasis. Angiography often reveals a highly vascularised tumour and will help to assess resectability. In the absence of widespread disease, pancreatic resection can provide long-term survival in metastatic RCC, although few cases have been reported with lengthy follow-up. The prognosis is better than for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Pancreatic metastasis, renal cell carcinoma, pancreatectomy

Introduction

Common sites of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) are lymph nodes, lung, bone, adrenals, liver, opposite kidney and brain 1. Pancreatic metastasis of RCC origin is rare (1.5–3% of all metastatic RCCs) 2, while a solitary RCC metastasis to the gland is even less common (1–2%) 3. Aggressive surgical treatment has been advocated for solitary metastases arising from RCC and would seem appropriate in selected cases.

We present three patients, two of whom had isolated resectable metastases treated by pancreatoduodenectomy. The third patient had multiple metastases and was kept under observation after declining chemotherapy. The presentation, surgical treatment and outcome of RCC metastatic to the pancreas are reviewed in the light of previous reports.

Case reports

Case No. 1

A 57-year-old man underwent a radical left nephrectomy with splenectomy and resection of the inferior vena cava for locally advanced RCC (Table 1). Three years later, investigation for anaemia revealed a friable haemorrhagic tumour on the medial wall of the duodenum; recurrent RCC was confirmed on biopsy. Abdominal CT, chest X-ray and bone scan showed no other lesions. Angiography revealed a highly vascularised tumour but no involvement of major vessels. Subsequently he had an episode of melaena. An angiogram was carried out, the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery was identified as the bleeding point and embolisation was performed.

Table 1. Details of three patients.

| Case | Age | Sex | Kidney affected | Years* | Chief complaint | Metastatic site | Size (cm) | Operation | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | M | Left | 3 | Melaena | Head of pancreas | 6 | PPPP | 9 years (lung and bone metastases) |

| 2 | 66 | M | Left | 0 | Asymptomatic | Head of pancreas | 4 | Whipple | 2 years (hilar node metastasis) |

| 3 | 55 | F | Right | 1 | Asymptomatic | Whole pancreas (multiple) | 2–3 (multiple) | None | 4 years (stable disease) |

PPPP, pylorus-preserving proximal pancreatoduodenectomy.

*Years from the time of RCC diagnosis.

The patient underwent pylorus-preserving proximal pancreatoduodenectomy (PPPP) in this department for a large but mobile tumour (6×5 cm) within the head of pancreas invading the duodenum (Figure 1). Frozen section histology confirmed negative margins, but subsequent analysis revealed grade II metastatic RCC with tumour extension to the anteroinferior surface of the pancreas. An incidental 1.5-cm neuroendocrine tumour with features of somatostatinoma was identified within the mucosa and submucosa at the duodenal resection margin.

Figure 1. .

Case no. I. Operative specimen showing a fungating tumour on the medial wall of the duodenum, which has been removed by PPPP (pylorus-preserving proximal pancreatoduodenectomy). The patient developed this isolated secondary in the head of pancreas following left nephrectomy for renal cell caxinoma 3 years earlier. He had first a refractory anaemia and then frank melaena.

The postoperative course was complicated by chest infection and transient renal insufficiency. Thereafter he remained entirely well for 8 years, when a follow-up CT scan revealed a large mass involving the left 6th and 7th ribs and a solitary nodule in the left lung, but no intra-abdominal recurrence. A bone scan confirmed widespread skeletal metastases. Palliative radiotherapy was given, and he is still alive 9 years after the pancreatic resection

Case No. 2

A 66-year-old man presented with a 2-month history of haematuria (Table 1). CT scan revealed an encapsulate 3-cm RCC plus a mass in the head of pancreas (4×4 cm), but no other distant metastases. During left nephrectomy the pancreatic mass was palpated but not biopsied. A postoperative percutaneous biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic RCC, and angiography showed a highly vascular but resectable pancreatic tumour. He was transferred to this department, where PPPP was performed with clear margins on frozen section. The definitive histology confirmed grade II metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma with negative margins and lymph nodes, but microscopic evidence of vascular invasion.

Postoperatively the patient required transient ventilatory support plus haemofiltration for renal insufficiency for 2 weeks. He was discharged after 1 month. One year later check CT scan revealed a suspicious hilar lymph node, which was excised at thoracotomy and found to contain metastatic RCC; there was no abdominal recurrence. Radiotherapy was administered to the chest, and he remains well 2 years after the pancreatectomy.

Case No. 3

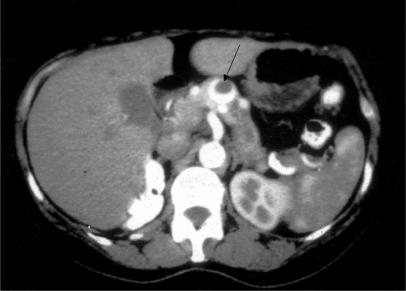

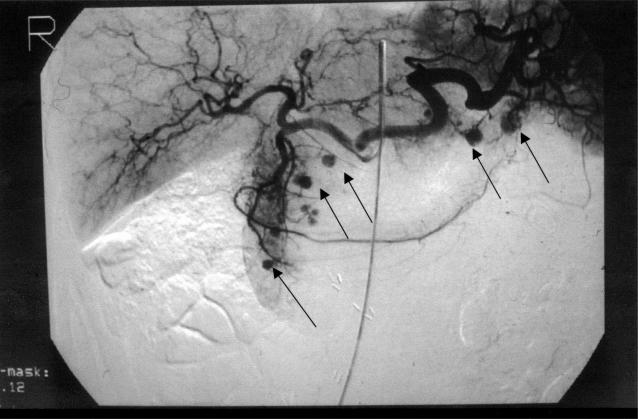

A 55-year-old woman had local excision and radiotherapy for a small, low-grade, invasive ductal carcinoma of the right breast, and in the same year she underwent right nephrectomy for an encapsulate RCC (Table 1). One year later abdominal CT showed two lesions in the head of pancreas, one of which was obstructing the pancreatic duct. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed slight distortion and narrowing in the head of pancreas and ductal obstruction at the junction of the body and tail. She declined treatment. After another 2 years, CT scan (Figure 2) and visceral angiography (Figure 3) revealed multiple hypervascular lesions (at least six) scattered throughout the pancreas. In addition there was severe compression of the origin of the portal vein (Figure 4). The largest lesion was in the body of pancreas (2.8 cm), and the pancreatic duct was dilated. Percutaneous biopsy obtained cells from a metastatic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney.

Figure 2. .

Case no. 3. Abdominal CT with intravenous contrast showing an enhancing tumour (arrow) in the neck of pancreas. The lesion is partly solid and partly cystic and was one of several renal cell metastases to the pancreas.

Figure 3. .

Case no. 3. Coeliac arteriogram showing several hypervascular lesions (arrows) in the head and tail of pancreas in a patient with multiple deposits of renal cell carcinoma.

Figure 4. .

Case no. 3. Venous-phage angiogram showing near total occlusion of the junction between the splenic and portal veins (arrow) with an obvious collateral circulation. The obstructing lesion in the neck of pancreas is hown in Figure 2.

The patient was offered treatment with α-interferon either alone or alternating with interleukin-2, but she decided not to proceed. She has remained remarkably well with no evidence of disease progression on follow-up CT (chest and abdomen) 4 years after the diagnosis.

Discussion

Metastatic spread of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) may occur to almost any organ of the body. Pancreatic metastases were found in 1.3–1.9% of autopsy cases with RCC 4 and in 2.0–8.0% of 101 consecutive patients with metastatic RCC in a clinical study 5. In most cases pancreatic metastases are part of widespread nodal and visceral involvement 6. Besides the kidney, the breast, the thyroid and the lung are the commonest sites for primary tumour 7.

Most patients with secondary pancreatic tumours present in a similar way to those with primary tumours. The symptoms described are abdominal pain, weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, anaemia and jaundice 8. There may be an abdominal mass and pancreatic dysfunction (endocrine or exocrine), but some patients have no symptoms at all 9.

In our series, two patients were diagnosed incidentally, one during the preoperative work-up and the other at 1 year after nephrectomy; both were asymptomatic. The reported incidence of asymptomatic pancreatic metastases ranges from 10 to 20% 10. The third patient developed gastrointestinal bleeding from ulceration of a large solitary metastasis of the head of pancreas into the duodenum. Bleeding was temporarily controlled by angiographic embolisation. The incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding as a main symptom of RCC metastasis varies between 10 and 60% among reported series 3,10.

Several imaging techniques can help to differentiate between primary and secondary pancreatic tumours. Spiral CT with intravenous contrast may be the best option, but small lesions (<5 mm) are difficult to demonstrate unless they give rise to a circumscribed bulging of the contour of the pancreas 11. Angiography will demonstrate a hypervascular tumour, and this finding can help to confirm the diagnosis when combined with the history and CT findings 7. Highly vascular tumours are much more likely to represent a metastasis than a primary pancreatic cancer, which tends to be relatively hypovascular 11. However, the differential diagnosis of hypervascular lesions in the pancreas includes neuroendocrine tumour, cystic neoplasm and focal lymphomatous infiltration as well as secondary deposits.

The tumours in the present small series involved the head of pancreas in two patients, while the third had multiple lesions scattered throughout the pancreas. Although data are limited, renal metastases appear to be rather more frequent in the head of pancreas than in the body or tail. Solitary metastasis is also more common than multifocal involvement 3.

The mode of spread of RCC to the pancreas is controversial: it may be haematogenous, along the draining collateral veins from a hypervascular primary tumour, or lymphatic by retrograde lymph flow from retroperitoneal nodes 10. The discovery of metastatic lesions generally implies a poor prognosis in cancer, with the exception of a few tumours such as RCC. Thompson and Heffess 3 reported a series of 21 patients who underwent pancreatic resection for RCC metastases with an 81% 5-year survival rate. The mean overall survival from the date of nephrectomy was 19.8 years, and the mean overall survival from the date of the pancreatic metastasis was 6.2 years. Sohn et al.12 described 10 patients who underwent pancreatic resection with an actuarial 5-year survival rate of 75%.

Although all the reported series are small, the survival of patients undergoing resection of pancreatic metastasis remains much better than that of patients with resected primary adenocarcinoma, for whom the 5-year survival is between 5 and 10% 13. Furthermore, Takashi et al. suggested that the survival rate is better in patients undergoing complete resection of the metastatic lesions than those who receive either no operation or palliative treatment 14. Two of our three patients underwent pancreatic resection and are still alive, albeit with thoracic metastases, at 2 and 9 years. The third patient with multiple pancreatic metastases clearly has a very slow-growing cancer and remains well 4 years after their incidental discovery.

References

- 1.Stankard CE, Karl RC. The treatment of isolated pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: a surgical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1658–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tolia B, Whitmore W. Solitary metastasis from renal cell carcinomas. J Urol. 1977;118:244–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)67155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson L, Heffess C. Renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas in surgical pathology material. Cancer. 2000;89:1076–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000901)89:5<1076::aid-cncr17>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tongio J, Peruta O, Wenger J, Warter D. Metastases duodenales et pancreatiques du nephro: a propos de quatre observations. Arm Radiol. 1977;20:641–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klugo RC, Detmers M, Stiles RE, Talley RW, Cerny JC. Aggressive versus conservative management of stage IV renal carcinoma. J Urol. 1977;118:244–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)57959-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willis RA. Butterworths; London: 1967. Pathology of Tumours4th edn; p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashimoto M, Watanabe G, Matsuda M, Dohi T, Tsurumaru M. Management of the pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: report of four resected cases. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1150–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robins EG, Franceschi D, Barkin JS. Solitary metastatictumors to the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2414–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirota T, Tomida T, Iwasa M, Takahashi K, Kaneda M, Tamaki H. Solitary pancreatic metastasis occurring eight years after nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. A case report and surgical review. lntj Pancreatol. 1996;19:145–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02805229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassabian A, Stein J, Jabbour N, et al. Renal cell carcinomametastatic to the pancreas: single-institution series and review of the literature. Urology. 2000;56:211–15. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00639-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faure JP, Tuech JJ, Richer JP, Pessaux P, Arnaud JP, Carretier M. Pancreatic metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: presentation, treatment and survival. J Urol. 2001;165:20–2. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Nakeeb A, Lillemoe KD. Renal cell carcinoma metastatic to the pancreas: results of surgical management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001;5:346–51. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooperman AM. Pancreatic cancer: the bigger picture. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:557–74. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takashi M, Takagi Y, Sakata T. Surgical treatment of renal cell carcinoma metastases: prognostic significance. Urol Nephrol. 1995;27:422–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02575213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]