Abstract

Background

Solid pseudopapillary tumor, otherwise known as solid and cystic tumor or Frantz tumor, is an unusual form of pancreatic carcinoma. Its natural history differs from the more common pancreatic adenocarcinoma in that it has a female predilection, is more indolent, and carries a better prognosis. Metastatic disease can occur, usually involving the liver, and its management is not well defined.

Case outline

A young woman was found to have a tumor situated in the pancreatic tail with seven synchronous hepatic metastases. Segments II and III were free of metastatic disease. A needle biopsy of the pancreatic lesion was non-diagnostic but suggested that the lesion was unlikely to be a typical adenocarcinoma. Initial treatment consisted of a distal pancreatectomy, which confirmed the diagnosis of a solid pseudopapillary tumor. Given the indolent nature of this pathologic entity as well as the patient's youth, an aggressive approach to treatment of the hepatic metastases was recommended. Because the liver was fatty, the right portal vein was embolized to produce hypertrophy of the left hemiliver. Six weeks later an extended right hepatectomy cleared the hepatic disease. The patient had an uncomplicated recovery, and she remains disease-free at 22 months.

Discussion

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas is a rare malignancy. Survival following primary resection approaches 95% at 5 years. Metastatic disease, although rare, usually involves the liver and/or peritoneum. Given the paucity of reported cases, the management of metastatic disease is, to date, poorly defined. This case demonstrates a favorable short-term outcome with aggressive surgical treatment of both the primary and metastatic tumor.

Keywords: pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumor, solid and cystic tumor, Frantz tumor, liver metastases, portal vein embolization

Introduction

Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas is a rare but characteristic neoplasm first described by Frantz in 1959 1. It afflicts young women, with a 10:1 predominance over men, at an average age of 24 years 2. Presenting features are usually vague and include abdominal pain, fullness, nausea, and vomiting due to a bulky tumor (mean size 11 cm) compressing local structures in the upper abdomen. The tumor is most commonly, but not always, localized to the tail of the gland.

Pathologically, the tumor is usually well circumscribed with regions of necrosis, hemorrhage, and cystic degeneration. A thick, fibrous capsule is often present, but a local desmoplastic reaction to the tumor is infrequent. Histologically, solid and pseudopapillary components are recognized with sheets of uniform, polygonal, epithelioid cells situated around prominent microvasculature stalks. Nuclei are consistent, usually round to oval, and demonstrate minimal pleomorphism.

Most primary tumors (85–90%) are localized to the pancreas at the time of diagnosis. Although they have low malignant potential, they can invade locally. However, recurrence is unusual following complete surgical resection. Long-term cure is achieved in >95% of cases in which disease is confined to the pancreas. Distant spread, when present, usually comprises synchronous disease to the liver and/or peritoneum.

Owing to the generally indolent biology of this tumor and its infrequency, the optimal management of metastatic disease is not well defined. Rare patients have been reported to live for extended periods with asymptomatic metastases. This report describes an aggressive approach to a patient with extensive metastatic disease confined to the liver.

Case report

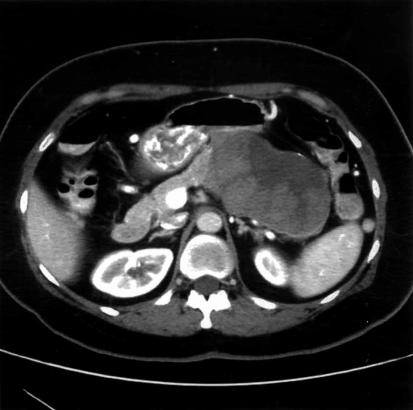

A 44-year-old woman, in good overall health, sought medical attention for progressive attacks of steady, aching left upper quadrant pain over a 1-year period. Other symptoms included fatigue and occasional nausea and vomiting not related to ingestion of food. There was no weight loss, jaundice, diarrhea, or flushing. Initial trans-abdominal ultrasound revealed a large mass in the tail of the pancreas. A subsequent computed tomogram (CT) of the abdomen demonstrated a 10.5×10.4×6.0 cm mass encasing the splenic vein (Figure 1). Multiple lesions were identified in the liver that were suspicious for metastases and appeared to spare segments II and III. Fine-needle aspirates of both the pancreatic and liver lesions demonstrated features suggestive of either neuroendocrine or acinar cell carcinoma of pancreatic origin. Further immunohistochemical staining was inconclusive.

Figure 1. .

Initial CT scan demonstrating a large, heterogeneous mass with cystic features situated in the tail of the pancreas. The splenic vein is thrombosed.

Given the unusual appearance of the tumor, its growth and indeterminate pathology, as well as the symptoms, laparotomy was performed. The bulky mass (11.5×10×6.5 cm) was resected by means of a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. There was a fatty liver with metastases in segments VIII and IVA but no portal lymphadenopathy. The patient had an uneventful 9-day postoperative course.

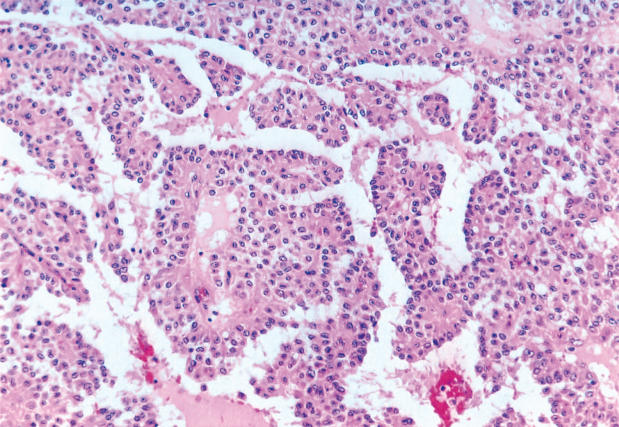

Histologic review of the lesion revealed a variegated, yellow tumor with hemorrhagic and necrotic areas admixed with solid areas. There was invasion into peripancreatic fat, but the surgical margins were negative. None of the nine lymph nodes recovered was positive for malignancy. Microscopic analysis revealed sheets of uniform polygonal cells with a pseudopapillary appearance and cholesterol crystals (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry was negative for chromogranin, but reactive for synaptophysin, CD56, and alpha-1-antitrypsin.

Figure 2. .

Histology of the original pancreatic tumor reveals features of a solid pseudopapillary tumor.

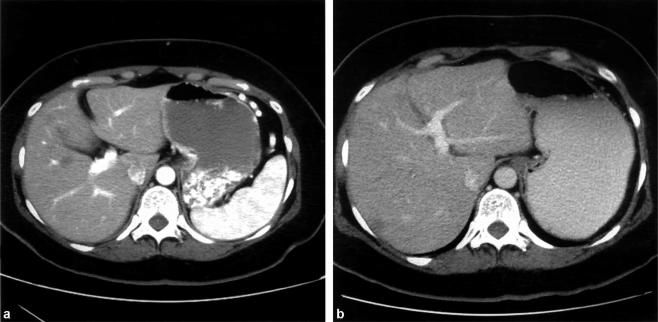

CT scan performed 3 months postoperatively illustrated seven hepatic lesions without progression, as well as a diminutive left lateral section (segments II and III); there was no evidence of recurrence in either the resection bed or the abdomen. With stable disease, consideration was given to a curative hepatic resection, requiring an extended right hepatectomy. Given the fatty parenchymal consistency and the small size of the proposed remnant, there was concern for the potential of postoperative liver dysfunction, so embolization of the right portal vein was successfully performed 3. Figure 3 demonstrates the hypertrophy of the left hemiliver obtained 6 weeks later.

Figure 3. .

CT performed 5 months after initial presentation and directly before hepatic resection demonstrates a hypertrophied left hemiliver. The right portal vein had been embolized 1 month earlier in anticipation of an extended right hepatectomy. (A) Before embolization. (B) One month post-embolization.

Five months after the original pancreatic operation, the patient underwent an extended right hepatectomy; intraoperative ultrasound showed no disease in the left lateral section. On pathologic assessment, the resection margins were clear of malignancy, and the histology was identical to the original pancreatic tumor. The patient was discharged on day 9, and by 1 month had made a complete recovery. After consultation with a medical oncologist, she declined any adjuvant chemotherapy. She remains disease-free at 22 months after the hepatic resection, and 27 months after removal of the pancreatic primary.

Discussion

This case illustrates many of the salient features of this rare tumor, which makes up <1% of all pancreatic neoplasms. Many reports have emerged over the last 25 years describing nearly 300 cases 2. However, despite generally consistent pathologic and clinical characterizations, some controversies remain.

The nomenclature of this pathologic entity is confusing and ranges from Frantz tumor to the recently favored papillary cystic neoplasm. We prefer the term solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas for two reasons. First, cystic changes are not a ubiquitous feature, and instead usually occur in larger lesions secondary to longstanding tumor necrosis. Secondly, the papillary appearance of the tumor is a result of cellular clustering around the microvasculature with more discohesive cells in the periphery, and is not due to the presence of true papillary stalks.

The precise cellular derivation of this tumor remains elusive, so routine immunohistochemical staining is not consistent in determining its phenotype. A variety of stain expressions have been described, representing neural, epithelial (ductal), and stromal (acinar) elements, but a general immunophenotype has emerged 4. These neoplastic cells regularly express vimentin, alpha-1-antitrypsin, and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin. Also, neuron specific enolase is usually faintly positive. The literature regarding the cellular differentiation of this tumor remains inconclusive. Arguments have been made that champion each of the three lineages described above. Given the inconsistent findings, an attractive hypothesis has been developed that these tumors originate from a ‘primordial’ pancreatic cell line. However, there are no conclusive data to support this line of reasoning.

The biologic behavior of solid pseudopapillary tumor is less aggressive than that of many other pancreatic tumors, and its prognosis is better. Surgical extirpation of the tumor will result in almost total survival (>95%) for those patients with tumors confined to the pancreas at presentation. Despite its potential for local infiltration, recurrence is rare following complete excision. Likewise, it is rare for metastases to develop metachronously.

Metastatic disease is present in up to 15% of cases, usually synchronous and confined to the liver or peritoneum. Lymphatic disease is not a feature. Death ascribed directly to the tumor is rare 5, and long-term survival (years to decades) has been described with asymptomatic metastases 6,7. Our patient presented with distant metastases at the age of 44, almost two decades after the mean age for presentation of this disease. This may suggest that advanced age is a prognostic factor for development of metastatic disease. Although the paucity of such cases precludes a definitive analysis of this concept, one series indicated that there was no age difference between metastatic and non-metastatic tumors, and furthermore their review of all metastatic cases in the literature revealed an average age of 29 years 8.

These findings suggest that metastatic disease in this setting is not particularly aggressive, and therefore should be considered more readily for surgical removal when feasible. Our patient opted for this pro-active approach to her disease, with excellent short-term results.

References

- 1.Frantz VK. Tumors of the pancreas, Atlas of Tumor Pathology, VII. In:. Fascicles 27 and 28. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1959;32–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao C, Guvendi M, Domenico D, et al. Papillary cystic and solid tumors of the pancreas: a pancreatic embryonic tumor? Studies of three cases and a cumulative review of the world's literature. Surgery. 1995;118:821–8. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80271-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdalla EK, Barnett CC, Doherty D, et al. Extended hepatectomy in patients with hepatobiliary malignancies with and without preoperative portal vein embolization. Arch Surg. 2002;137:675–80. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klimstra DS, Wenig BM, Heffess CS. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a typically cystic carcinoma of low malignant potential. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000;17:66–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsunou H, Konishi F. Papillary-cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. A clinicopathologic study concerning the tumor aging and malignancy of nine cases. Cancer. 1990;65:283–91. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900115)65:2<283::aid-cncr2820650217>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa T, Isaji S, Okamura K, et al. A case of radical resection for solid cystic tumor of the pancreas with widespread metastases in the liver and greater omentum. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1436–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sclafani LM, Reuter VE, Coit DG, et al. The malignant nature of papillary and cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Cancer. 1991;68:153–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910701)68:1<153::aid-cncr2820680128>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishihara K, Nagoshi M, Tsuneyoshi M, et al. Papillary cystic tumors of the pancreas: assessment of their malignant potential. Cancer. 1993;71:82–92. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930101)71:1<82::aid-cncr2820710114>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]