Abstract

Background

Liver resection for secondary malignancy has become the standard of care in appropriately staged patients, offering 5-year survival rates of >40%. Reports of laparoscopic liver resection have been published with increasing frequency over the last few years. In these small series approximately one-third of all operations have been for malignancy, but survival figures cannot be assessed yet.

Methods

A retrospective review of all laparoscopic liver resections performed by four surgeons in Brisbane between 1997 and 2004 was done. Follow-up was by regular patient review and telephone confirmation.

Results

Of 84 laparoscopic liver resections, 33 (39%) were for malignancy; 28 of these were for metastases (22 colorectal). Thirteen patients had left lateral sectionectomy with minimal morbidity; nine right hepatectomies were attempted and six cases of segmental or subsegmental resection were performed. Survival rates in 12 patients followed for 2 years with colorectal secondaries were 75% with 67% disease-free.

Discussion

Laparoscopic liver resection is feasible in highly selected cases of malignant disease. Patients need to be appropriately staged and surgeons need a broad experience of open liver surgery and advanced laparoscopic procedures.

Keywords: laparoscopic liver resection, liver metastases

Introduction

Despite widespread acceptance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy over the past 15 years, minimal access surgery on the adjacent liver has been less enthusiastically adopted. There are two principal reasons for this. Firstly, many surgeons are fearful of bleeding, gas embolism, and the sheer loss of control that could ensue from laparoscopic approaches to the liver. Secondly, it seems that it is quite rare in world surgery to have surgeons with experience and expertise in both open hepatic surgery and advanced laparoscopic procedures.

Surgical resection of liver metastases can offer 5-year survival of 20–40% 1,2. As long as standard oncologic surgical principles apply, laparoscopic surgery should offer a survival at least as good. This paper documents our experience with laparoscopic resection of liver metastases.

Patient selection involves consideration of sex, body size, previous surgery and site of the lesion. Women with small slender livers are more amenable to laparoscopic approaches. Lesions on the edge of the liver are easily approached, and left lateral sectionectomy is ideally suited. The over-riding principle as in all oncologic liver surgery should be a clear surgical margin.

Instruments and techniques

Laparoscopic liver surgery began in Brisbane in the mid-1990s as a natural progression from laparoscopic staging. Initially excision biopsy of surface metastases using scissors and diathermy was performed. Harmonic shears allowed subsegmental and some segmental procedures to be attempted but the introduction of linear staplers and in particular the 60-mm vascular stapler (Tyco, Norwalk, CT, USA) allowed more extensive parenchymal division 3,4.

Harmonic shears have been reviewed in several open and laparoscopic series 5. They are useful around the edge of the liver but may lead to bleeding as they fail to control larger hepatic veins. Staplers are effective as mechanical finger fracture tools that squash parenchyma and staple larger vessels. They may not fire properly if too much hepatic tissue or large clips are in their path.

Other devices that have been reported for parenchymal dissection include bipolar diathermy, ultrasonic aspiration devices and the jet cutter 6. To help control minor bleeding the argon beam coagulator has been recommended. One must be cautious and have low intraabdominal pressure when using this device laparoscopically, as fatalities have been reported following presumed argon embolisation 7. The refinements of inline radio frequency ablation may increase the laparoscopic options as lines of transection can be safely ablated to allow bloodless resection of liver 8.

Margins of at least 1 cm are preferred and easily obtained when preoperative imaging has shown lesions to lie well clear of the parenchymal transection line. Laparoscopic ultrasound is essential to define margins when performing non-anatomic resections or whenever the line of transection is not easily defined. It can also be useful in identifying larger vessels which may require stapling.

The patient is asleep and prone with a low CVP. Rolling to 45° will help expose the lateral aspect of the liver. Port sites are positioned to allow access of the 12-mm diameter staple gun to fire along the predicted lines of transection. A 30° 10-mm laparoscope is essential and an angled 5-mm scope can be useful. Specimen removal is always done with a retrieval bag or plastic wound protection device, removing the tumour intact without morcellation. The umbilical wound can be extended or a new muscle-splitting incision made.

Left lateral sectionectomy

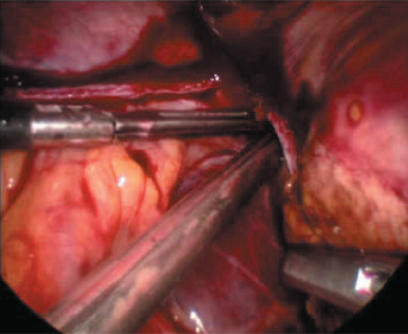

Left lateral sectionectomy is ideally suited to laparoscopic surgery and if the tumour is well clear of the falciform ligament we believe a laparoscopic approach is the procedure of choice. The technique is straightforward and in a slender liver very simple. The left triangular ligament is divided back to the left hepatic vein taking care to avoid the phrenic and left hepatic veins and pericardium. After dividing the avascular bridge of liver tissue beneath the round ligament the stapler is placed to the left of the falciform ligament with arms above and below segment III. The stapler will squash the parenchyma opposing the anterior and posterior surfaces of Glissen's capsule to give a solitary pinched staple line (Figure 1).

Figure 1. .

Pinching effect of endoGIA vascular stapler in left lateral sectionectomy.

In a more bulky liver two layers of transection may be needed. The thin arm of the stapler is insinuated into the liver substance through a diathermied window in the capsule 15 mm below the anterior surface of the liver. The gun is advanced cautiously until resistance is reached and then fired. A second firing is then done to include the inflow structures beneath the first firing. The process is continued and up to eight guns may be needed in a bulky or fatty liver. Occasionally bleeding from the staple line or nearby can occur and may need suture ligation, but this can often be controlled by a further firing of the stapler, especially if the left lobe is fully mobile.

Our current preference is to perform this procedure using three ports with a 12-mm port at the umbilicus and two 5-mm lateral ports, one of which can be used for a 5-mm laparoscope to allow the stapler to be placed through the umbilical port. The specimen can be placed in a retrieval bag and morcellated if benign or removed through an extended umbilical incision, pfannensteil, or appendix-type incision.

Segmental resections

Segmentectomy and subsegmental resections of liver lesions can be achieved when the lesion lies quite peripherally and the amount of parenchymal transection needed is relatively small. Even small lesions on the dome or the posterior aspect of the liver can be technically very difficult as trans abdominal approaches do not allow easy access of instruments. To remove a 1-cm lesion on the dome of the liver with a 1-cm margin means cutting through a hemisphere of liver substance with a 3-cm diameter and 2 cm into the liver. Until technology is improved, attempting these lesions laparoscopically may result in bleeding and poor surgical margins.

Segment VI can often be easily approached and occasionally liver tumours hang down segments V and VI and a safe line of transection can be easily achieved. Port placement involves consideration of the application of a linear stapler from a reasonable distance away from the liver to allow the jaws to open widely. Lesions in segment IVb can be excised with harmonic shears being mindful of the recurving inflow structures.

Right hepatectomy

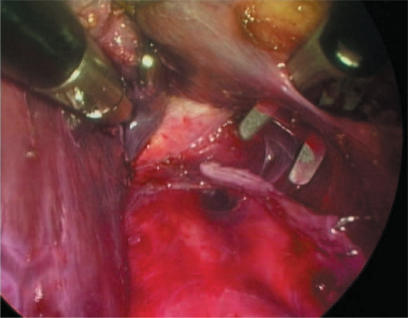

Right hepatectomy is a much more technically demanding procedure. Our surgical technique has recently been reported in detail 9. The procedure can be broken down into three steps, the first being division of the portal structures individually using clips and linear staplers. The second stage involves dividing the minor hepatic veins beneath the liver using harmonic shears and clips. One continues up the vena cava to divide the right hepatic vein from beneath the liver using a linear stapler (Figure 2). The third stage involves parenchymal division which can be performed with a combination of harmonic shears and linear staplers with suture ligation of any bleeding vessels. This technique is only suitable for relatively slender livers and, of course, any tumour should be well clear of the principal plane of the liver. Hand assistance has been tried in two of our right hepatectomies. On both occasions, an assistant's left hand was used to elevate the liver, leaving the operating surgeon free to continue with a two-handed technique.

Figure 2. .

Laparoscopic right hepatectomy – retrohepatic tunnel with staple line having just divided right hepatic vein.

Cautionary note!

These procedures can be straightforward but disasters can occur if one is not mindful of the possibilities and able to handle the problems. The ability to suture quickly in awkward and stressful situations is essential. Staplers must be used with caution around the vena cava and porta. These vessels can be narrowed considerably if care is not taken to identify vascular junctions accurately. It must be stressed that these operations (especially right hepatectomy) should not be attempted unless one is experienced with the instruments and techniques needed for advanced laparoscopic surgery.

Staging

Laparoscopic staging is performed in all our patients with liver metastases. Grading systems have been used to define the population that benefits most from laparoscopic staging 10,11. In our practice those patients with a higher risk of unresectable disease may undergo laparoscopic staging as a separate procedure. Low risk patients can have a laparoscopy immediately prior to laparotomy. Laparoscopic resection evolved from such aggressive staging but it still must complement adequate radiological work-up. All patients need at least a three-phase high quality CT scan or MRI. When available, if a primary tumour is suitable, as in colorectal cancer, a PET scan should be obtained.

Results

In all, 84 major laparoscopic liver resections have been attempted by four surgeons in Brisbane since 1997: 41 of these were left lateral sectionectomies, 13 right hepatectomies and 17 segmentectomies. There was one left hepatectomy and the remainder were subsegmental resections. The conversion rate was 9.4%.

Thirty-three of the patients underwent surgery for malignancy and 28 of these were for metastases-22 colorectal, 2 gastric, 2 carcinoid, 1 lung and 1 renal cell. Of the 28 resections for metastases, 13 underwent left lateral sectionectomy, 9 underwent right hepatectomy, 5 underwent sectionectomy and 1 had a non-anatomic resection. The operative details are given in Table 1. Left lateral sectionectomy is confirmed as the least demanding procedure with no conversions and minimal blood loss. There were no deaths, but major morbidity occurred in four patients: one delayed bleed not requiring surgery in a left lateral sectionectomy patient on anticoagulation for a prosthetic heart valve; a wound dehiscience in a laparoscopy-assisted right hepatectomy; two bile leaks in the sectionectomy group.

Table 1. Operative details of 28 laparoscopic resections for liver metastases.

| Procedure | Total no. (lap assist)–conversion | Duration | Mean blood loss (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Left lat. section. | 13 (0)–0 | 100 (40–165) | 115 ml (50–350) |

| Right hepatectomy | 9 (3)–2 | 266 (200–370) | 800 ml (500–2000) |

| Other | 6 (0)–2 | 81 (45–145) | 400 ml (20–1200) |

The mean margin was 11 mm with a range of 0–30 mm. Margins were >1 cm in 15 of 28 cases (54%). One patient had a positive margin and died 12 months later with lung metastases. Mean follow-up of the 22 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer was 20 months with a range from 1 to 44. Thirteen are alive without recurrence, two are alive with recurrence (one local and the other underwent an open right hepatectomy 16 months after a laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy). Six have died with disease. One patient died 12 months after her hepatectomy from metastatic colorectal cancer with melanoma. The overall and disease-free survival rates in the 16 patients followed for 1 year with metastatic colorectal cancer were 88% and 81%, respectively. In the 12 patients followed for 2 years, the rates were 75% and 67%.

In patients with non-colorectal metastases, mean follow-up was 9 months (range 4–14 months). Two patients with metastatic gastric cancer died at 6 and 14 months, respectively. The patient with lung cancer (SCC) died at 14 months. The two carcinoid patients are alive and disease-free at 4 and 13 months. The renal cell cancer patient underwent a left lateral segmentectomy for an 8-cm tumour that ruptured on the day prior to surgery. She developed a solitary port site metastasis at 4 months and is alive and disease-free 4 months after its resection.

Discussion

Laparoscopic liver surgery is increasing in popularity. A recent review article has collated 700 reported cases of laparoscopic liver resection with small series reported from all around the globe 12. Two years previously the same group gathered only 200 patients 13. It seems that techniques are evolving from the mid-1990s when the first ground-breaking reports by Huscher appeared 14,15. The review of 700 patients points out that only 30% of the procedures performed were for malignant disease. This reflects our experience, where 33 of 84 (40%) laparoscopic resections were for cancer.

Most of our patients having liver resection undergo open resection after laparoscopic staging. We would agree with Cherqui that about 12% of all liver resections can be performed laparoscopically with the current limitations of technology 16. These patients are selected on the basis of practising safe oncologic surgery. After appropriate staging, patients with lesions well clear of the line of parenchymal transection can be offered a minimal access resection. We are laparoscopic hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal surgeons with a long interest in advanced laparoscopic procedures and a belief that one's skills will improve only by performing most abdominal operations laparoscopically.

Left lateral sectionectomy is the most frequently performed laparoscopic procedure 17,18. There have been several different techniques reported, but we and others 19 find a simple stapling technique without inflow or outflow control to be safe and efficient for most cases. Our results in this operation reflect this with no conversions and minimal blood loss.

Resection of other segments or subsegmental resections can be more problematic. Only lesions in easily accessible lower liver segments with not too much parenchymal transection should be attempted. Laparoscopic ultrasound is essential for these cases to ensure adequate margins 20 and identify large vessels. Even then, this can be a difficult procedure, as evidenced by the high conversion and complication rates in our series (Table 1).

Right hepatectomy is technically demanding, time-consuming and emotionally draining when performed laparoscopically. We have shown it to be possible in selected cases, and see its development most likely to be as an assisted procedure. The mobilisation of the liver off the vena cava by creating a retrohepatic tunnel can be straightforward laparoscopically. There may be an oncologic advantage in dividing the venous drainage of the right lobe in this way without the usual lifting and squeezing of the liver that occurs at standard open right hepatectomy. The procedure could then be completed using hand-assist or through a small incision with a Belghitti sling.

The main operative problem is control of unexpected bleeding and to persist laparoscopically one needs to be adept at suturing promptly and effectively. Gas embolism is surprisingly rare clinically 12. A trial in pigs using transoesphageal ultrasound found a much higher incidence of gas embolism in laparoscopic liver resection compared with open liver resection with significant deleterious effects on cardiac output 21. This does not appear to be the case in humans. None of our patients suffered a diagnosed or suspected clinical event and we see no need to complicate the issue by using body wall lift gasless techniques. Carbon dioxide is far more soluble than air. We use a pressure of 12 mmHg with low central venous pressure and if open veins are seen we close them expeditiously with a stapler.

Are there any oncologic advantages or disadvantages to the laparoscopic procedure per se? A recent and oft quoted trial of laparoscopic versus open colectomy for cancer reported by Lacy et al. suggests a survival advantage in the laparoscopic group 22. It is tempting to surmise that a procedure with minimal liver squeezing done through small incisions with less immune upset may lead to better long-term results but we will have to wait some years for this to be confirmed in liver surgery.

One of our patients suffered a port site metastasis 4 months after left lateral sectionectomy. This patient had an 8-cm renal cell cancer that had ruptured prior to surgery. Although initial reports suggested that port site recurrence would become a major problem with laparoscopic surgery for cancer, in practice the incidence appears no different to that seen at open surgery 16,23.

Survival following liver resection for cancer is directly related to margin 24. There is no point in doing a minimal access procedure if it will compromise the long-term result. Two of our conversions were to ensure adequacy of tumour clearance and in the one patient with positive margins, perhaps conversion should have occurred. A comparative study from Turin looking at 30 laparoscopic liver resections showed similar tumour margins to matched open resections (>lcm in 56%) 25. A similar study from Oslo showed a margin of >1 cm in 15/21 (71%) laparoscopic resections, and 10/16 (63%) open resections 26. Our results of 13/28 (54%) in all metastases are similar but should be better. One can rightly ask whether an open operation in the patients with lesser margins might have improved results.

Survival data are not yet available from the two comparative studies mentioned above but Gigot et al. in reporting the results of a multicentre audit found a 2-year disease-free survival of 53%, but only 12 of the 27 patients undergoing laparoscopic liver resection had colorectal metastases 20. Our small series from Brisbane has demonstrated reasonable oncologic results with 2-year overall and disease-free survival of 75% and 67%, respectively, in colorectal patients. It should not need saying that all surgeons performing this surgery should audit and present or publish their results.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic liver resection can offer selected patients with liver metastases successful surgical treatment without the disadvantages of a major surgical incision. Patients need to be appropriately staged and tumours need to be well clear of the line of parenchymal division to ensure adequate surgical margins. Laparoscopic surgery of the liver will continue to be performed in centres with expertise in both advanced laparoscopy and open hepatic surgery and the oncologic results need regular review. Perhaps the time has come for a randomised trial in, for example, laparoscopic left lateral sectionectomy.

Improvements in technology will continue and there should be no reason why a laparoscopic approach cannot complement the great advances in open liver surgery that have occurred over the last 20 years.

References

- 1.Rees M, Plant G, Bygrave S. Late results justify resection for multiple hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strong RW, Lynch SV, Wall DR, Ong TH. The safety of elective liver resection in a special unit. Anst N Z J Surg. 1994;64:530–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1994.tb02279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaneko H, Otsuka Y, Takagi S, Tsuchiya M, Tamura A, Shiba T. Hepatic resection using stapling devices. Am J Surg. 2004;187:280–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Champion JK, Williams MD. Prospective randomized comparison of linear staplers during laparoscopic roux-en-y gastric bypass. Obesity Surgery. 2003;13:855–60. doi: 10.1381/096089203322618641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidbauer S, Hallffeldt KK, Sitzmann G, Kantelhardt T, Trupka A. Experience with ultrasound scissors and blades (ultracision) in open and laparoscopic liver resection. Ann Surg. 2002;235:27–30. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200201000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rau HG, Butler E, Meyer G, Schardey HM, Schildberg FW. Laparoscopic liver resection compared with conventional partial hepatectomy–a prospective analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:2333–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kono M, Yahagi N, Kitahara M, Fujiwara Y, Sha M, Ohmura A. Cardiac arrest associated with use of an argon beam coagulator during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:644–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Croce E, Olmi S, Bertolini A, Erba L, Magnone S. Laparoscopic liver resection with radiofrequency. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:2088–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Rourke N, Fielding G. Laparoscopic right hepatectomy: surgical technique. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:213–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarnagin WR, Conlon K, Bodniewicz J, et al. A clinical scoring system predicts the yield of diagnostic laparoscopy in patients with potentially resectable hepatic colorectal metastases. Cancer. 2001;91:1121–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010315)91:6<1121::aid-cncr1108>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metcalfe MS, Close JS, Iswariah H, Morrison C, Wemyss-Holden SA, Maddern GJ. The value of laparoscopic staging for patients with colorectal metastases. Arch Surg. 2003;138:770–2. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.7.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogula T, Gagner M. Current status of the laparoscopic approach to liver resection. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2004;14:23–32. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v14.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biertho L, Waage A, Gagner M. Laparoscopic hepatectomy. Ann Chir. 2002;127:164–70. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(01)00709-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huscher CG, Lirici MM, Chiodinia S, Recher A. Current position of advanced laparoscopic surgery of the liver. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1997;42:219–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huscher CGS, Lirici MM, Chiodini S. Laparoscopic liver resections. Serrun Laparosc Surg. 1998;5:204–10. doi: 10.1177/155335069800500308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherqui D. Laparoscopic liver resection. Br J Surg. 2003;90:644–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Descottes B, Glineur D, Lachachi F, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection of benign liver tumours. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-9047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.IHPBA Brisbane2000, Terminology of Liver Anatomy & Resections. HPB 2000;2:333–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linden BC, Humar A, Sielaff TD. Laparoscopic stapled left lateral segment liver resection – technique and results. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:777–82. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(03)00099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gigot J-F, Glineur D, Azagra JS, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection for malignant liver tumours. Ann Surg. 2002;236:90–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200207000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmandra TC, Mierdl S, Bauer H, Gutt C, Hanisch E. Transoesophageal echocardiography shows high risk of gas embolism during laparoscopic hepatic resection under carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum. Br J Surg. 2002;89:870–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacy AM, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2224–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allardyce RA. Is the port site really at risk? Biology, mechanisms and prevention: a critical view. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:479–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rees M, John TG. Current status of surgery in colorectal metastases to the liver. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:341–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morino M, Morra I, Rosso E, Miglietta C, Garrone C.Laparoscopic vs open hepatic resection: a comparative study. Surg Endosc 2003;17:1914–18(Epub 2003 Oct 28). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mala T, Edwin B, Gladhaug I, et al. A comparative study of the short-term outcome following open and laparoscopic liver resection of colorectal metastases. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1059–63. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]